Paco is in a world of trouble. He has this noose around his neck, see, and he is balanced ever so precariously on this tombstone, which is just about to tip over on the godforsaken plain. Miles and miles of sagebrush. Not a human being in sight. Check that. There is one, well, semi-human nearby. Only a couple of hundred yards away, really. The problem is, Paco’s lone potential savior is the very man who strung him over the hanging tree to begin with. Paw’s last best hope lives with this squinting, poncho-clad, cigarillo-smoking, black-hat-wearing, lean, long drink o’ water who likes killing better than breath itself Oh, things do look grim for the sleazy little Mexican hustler. Any second that marker is going to tip over and it’ll be snaperoo city. So Paco—tough, wily Paco—is reduced to pleading, belly-screeching for help.

“Come back… Come back… Don’t leave me here!”

But The Man With No Name is just ambling onward, receding into the purple-speckled sky. The son of a bitch has done that the entire time the two of them have been hustling for gold, just ambling about, squinting and smoking, and every so often drawing crossed guns from underneath his serape and blowing big holes in twenty, thirty, forty guys at a time. And it doesn’t look like he’s about to change now. There he goes, as pleasant and casual as you like, riding slowly, slowly away, His horse’s tail brushes away the annoying desert mosquitoes and you know The Man With No Name is enjoying every second Paco is twisting, sweating, pissing himself as his sweaty, scumbag life drips away. Oh, Lord, the Man is cool.

Now Paco is reduced to twittering birdcalls—“Don’t leave Paco… don’t leave him… Hey… Hey…”—talking about himself in the third person. He’s already cashing it in. The Man With No Name is just at the crest of an impossibly barren hill. Around him is something that looks like burning driftwood. He turns slowly, ever so slowly, squints into the camera and takes out his rifle. With one hand, he brings the sight up to eye-slit level and fires. Paco’s rope snaps, the mangy greaseball crumbles to the ground. He gets up, starts to run for the hill. The Man With No Name has a heart after all. He hasn’t let old Paco hang. Now he’ll get him out of this hellhole of a desert. He runs, runs…

But, oh, Sweet Virginia, The Man With No Name is turning around again. Receding into the mirages at that slow, sadistic sidle, just fast enough to stay out of Paco’s reach. And Paco is running, screaming. “Wait! Wait, you devil. Wait for Paco!” And he keeps running, as the eerie conch shell music crescendos and The Man With No Name ambles toward the setting sun.

It is 1969 and I am just emerging from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, starring this actor I vaguely remember from the TV show Rawhide, a guy named Clint Eastwood. Truth be told, I went to the theater for laughs, because my liberal literary friends across the country had been telling me that the ultimate in moronic mindlessness had been born, the dumbest actor of all time, starring in the most ridiculous movie since Teenagers from Outer Space. So I had gone, stoned on uppers, grass, and Romilar, ready for an experience in High Camp, like seeing The Son of Flubber or the Three Stooges in Spanish (for my money, still one of the primo experiences to be had on TV). What I had in mind was ecstasy; I would get stoned on the purity of the lameness.

But I had been surprised, shocked, stunned. Even through the haze of my chemical aids I had seen something in this discarded TV actor that I hadn’t expected. To put it bluntly, I had been thrilled by the damned movie, and this embarrassed me. I strolled out and tossed off the usual liberal folderol—“He sure does squint good”—but I felt like a coward. For what my frontal brain was telling me and what my visceral reactions truly were… well, Jack, they was at definite odds. There was something about him—that poncho, that cigar, that black hat… the way he held the gun. Goddamn. Though I wouldn’t have the courage to say it, I knew right then that here was the heir to John Wayne.

What had gotten to me was Clint Eastwood. The guy was the Ultimate Legendary Mythic Cowboy, the Stranger from Nowhere.

But more than that, he was also the Rolling Stones; there was a wonderful sadistic/good-guy edge going on there, everything done so damned stylishly that he just had to know that he was overdoing it. (Or did he? No, he couldn’t.) His movies were “spaghetti Westerns,” and it was important not to like anything D-U-M-B, wasn’t it? And whatever else, even the movie crit crowd had to admit that the picture was “visually rich.”

But to hell with that stuff: What had gotten to me was Clint Eastwood. The guy was the Ultimate Legendary Mythic Cowboy, the Stranger from Nowhere. There was a little of Richard Widmark’s Tommy do in him, the thrill of the sensual sadist, like Jagger singing “Paint It Black.” Hey, this here Clint Eastwood was one mean motherfucker. (But I’d never tell a soul.)

Well, those days are long gone. Clint Eastwood—that maligned, critic-punished, low-graded, scoffed-at, cast-off, spaghetti Western-making, Dirty Harry “fascist” (critic Pauline Kael’s term), male-chauvinist, robot-faced, talentless apex of nadir—has only gone on to become the biggest superstar in the film world. He has been the top box-office draw, or close to it, in nine out of the last ten years. And now even such highbrows as John Simon and Andrew Sarris are grudgingly giving ground. These days it’s a basic tenet of all those with literary pretensions that a “sense of irony” is the common denominator of heightened sensibility. So now critic Molly Haskell is commenting on Clint Eastwood’s “ironic stance.” Just like they used to with Henry “Hank” James and other American Real Honest-To-God Artists. So the worm has turned indeed. No longer do I have to defend seeing Dirty Harry or Magnum Force forty times. Clint Eastwood is okay to like.

Absolutely no parking—reserved for Clint Eastwood says the sign in front of Big Clint’s Big Sleep-style Mexican hacienda on the Warner Brothers lot in Burbank. God knows I’m not going to try and cross him. He could hop out of his car and, seeing me in his office, string me up to the chandelier. Little reptilian eyes glowering at me, he tips the chair under my feet…. Hellfire, let me park in Santa Monica and bus back out here rather than risk that!

Once inside, I don’t feel any more secure. Everywhere are posters of Big C. Here, he’s hanging from a mountain in The Eiger Sanction; there, tracking you with the infamous .44 Magnum from a Dirty Harry world he never made (but is sure as hell going to clean up); over there he’s holding a killer cannon in Thunderbolt and Lightfoot.

Suddenly (could Clint appear in any other way?) he is ambling across the room, smiling a cascade of white teeth, looking down at me from six-foot-six of pure sinew and grit. And it’s not the Man With No Name squint, or Dirty Harry’s killer smile; he seems actually friendly, all genial Californian charm. And definitely the most handsome person of either sex I’ve ever met. Christ, at forty-seven, the way he is poured into his Levis, leather boots, and powder-blue T-shirt with a sunburst of Aztec god on the front… the sun god comes off a poor second.

“Good to see you,” he says. “Come on into the office.”

Aha, I think, the office. Gun racks, victims’ shrunken heads, gorgeous dames whom he never kisses. But alas, it’s anybody’s comfortable California exec office, with a big mahogany desk, Mexican couch, some homey table lamps. Nothing faintly evil, macho, or even tacky-dumb. The only sign that it’s Eastwood’s lair at all is the weight machine in the corner and some sporting trophies on top of a big Spanish cabinet. Golf, tennis-civilized sports.

It’s too normal. Eastwood is offering me a beer, sitting down on the couch, stretching out his long, lean body, getting down-home cozy and running through his early years, when his family drifted around California, finally settling in Oakland. It says here he went to trade school.

Though Eastwood’s heroes are all men of action, they are also painfully shy. They look as though they want to speak but aren’t sure enough of their words. They seem afraid to appear foolish.

“I took aircraft,” he says casually. “I rebuilt one plane engine, and a car engine too. I never had any dough so I could never afford anything very nice. I think kids go through certain times, in certain towns, where cars are their whole life. Cars first, chicks second.”

“Yeah,” I say, “that’s how it was in Baltimore. Baltimore and Oakland are a lot alike… working-class towns. We used to go down to junkyards and buy engines, bring them back and open them up, just to see how they worked.”

Eastwood smiles. “I used to buy engines. I used to go to junkyards and buy engines on spec. I remember once I bought a ’39 Ford, a modified T-Roadster, and the damn thing ran like a charm. I was really surprised.”

He seems to have been more interested in cars than in acting. His film bio says he never acted in a school play.

“No,” he says. “Once, when I was in junior high school, I did a one-act play. It was part of an English class, an assignment, and the teacher gave me the lead. I guess to help me, because I was an introverted kid.”

For a second I’m surprised, but then it seems natural. Though Eastwood’s heroes are all men of action, they are also painfully shy. They look as though they want to speak but aren’t sure enough of their words. They seem afraid to appear foolish. Obviously, then, Eastwood draws on his own introversion, gets an aesthetic distance from it and creates that sense of menace that lurks just beneath the surface of all his best and most violent creations.

“We had to put it on for the senior high school, and I was so scared I almost cut school that day. But I finally did it—it was a comedy—and it went over fairly well. So I thought, ‘I managed to do that.’”

His first comedy. Eastwood’s movies are all comedies. His natural flair for hyperbole creates a wild, black humor and it seems important that his first role, the one in which the introverted grease monkey first realized he had some son of artistic sensitivity, was a Iaugher. Yet, one can’t be sure. The word on the street is that Clint is perhaps not so… bright. Maybe he just doesn’t know his movies are a riot. I am still more than a little jumpy about asking him; what if he doesn’t find it so funny and pulls his .44?

“So it was a comedy?” I venture timidly.

“Yeah,” says Eastwood, leaning back in the perfect California mellow slouch. He seems so damned relaxed. Maybe I can risk it. “One of the, ah, things that makes your movies different from say, Charles Bronson’s, is the humor… wouldn’t you say?”

“Yeah,” he squints. “I like action adventure movies, but there is a humor aspect. I love to laugh, and I enjoy it when other people laugh, and I hope other people do.”

Dirty Harry is walking headfirst into a trap. Some psycho is hell-bent on chopping off his hands and gouging out his eyes. Harry is walking down a dark alley. The killer waits. It looks like the Big Casino for our man. I am on the edge of my chair, terrified. Behind me, a black guy can no longer stand the angst. He stands up in his seat and begins to scream:

“Ceee Eeeeeeee!” he yells. “C.E. won’t fall for that shit. No way. That’s my main man, C.E.”

“‘C.E.,’” Eastwood laughs. “C.E. won’t fall for that shit! I’ll have to remember that one. I like that. That guy has paid his dough and he just wants to be taken on a trip. Now, there’s all kinds of levels. Hopefully, you can move people on other levels, too. But that’s great, when he’s talking with you. I’ve been in movies where the guy was talking against you. That’s not so great.”

“Yeah,” I laugh. “I couldn’t believe you were in Francis the Talking Mule.”

Eastwood chuckles. “I’ve been in some of the worst films ever made. I started out at Universal with one- or two-liners. Sometimes, if you were lucky, you had three or four lines. Say, are you all right?”

Eastwood has noticed that I am filling up scores of handkerchiefs with nasal New York venom. “You ought to have some tea and an oatmeal cookie,” he says.

Nobody ever took an oatmeal cookie from Dirty Harry.

Not me. Nobody ever took an oatmeal cookie from Dirty Harry. It’s probably got tiny projectile “oats” which spring out and perforate your jaw.

“No,” I say. “I’m not allowed anything with caffeine in it.”

“But this is herb tea,” Clint assures me. “No caffeine. And these oatmeal cookies are out of sight. Wait, I’ll get them for you.”

He returns a few seconds later with a steaming mug and the largest oatmeal cookie in the Western Hemisphere. He waits for my judgment.

“Delicious,” I say.

“See,” says Clint. “That’s just what you need.”

“Right.” I take another bite. Not bad. “I understand you did a lot of rough gigs before you became an actor,” I say through the crumbs.

“I was a firefighter, a lumberjack, I was in the army and I dug swimming pools,” he offers, “but I never knew what I wanted to do. A lot of people have long-range ambition, but I never had that. I thought I might be a musician for a while, but every time I’d get going there’d be an interruption.”

He stops, stares at the ceiling.

I wonder why he was aimless for so long. “What did your parents do?”

“Well, later in life, when we lived in Oakland, my dad worked for a container corporation. Before that he worked as a pipe fitter for Bethlehem [Steel] and in gas stations.”

“So, like your characters, you kind of wandered.”

“I just kept sinking lower and lower in my seat. I said to my wife, ‘I’m going to quit, I’m really going to quit. I gotta go back to school, I got to start doing something with my life.’ I was twenty-seven.”

“Sure,” Eastwood says. “And I use that. My dad finally started doing well about the time I was out of high school, but by that time I was pretty much on my own anyway… drifting around.”

There is a hint of loneliness in Eastwood’s voice. Not self-pity, but something lost, something he missed in childhood: security, closeness. Clearly, he has fed off that loss.

“You had no intention of being an actor in those days?”

“Jesus, no,” Eastwood smiles. “I always felt the same thing that everybody felt about actors, that they were extroverted types who like to get up in front of two thousand people and make an ass out of themselves. I still don’t like to get up in front of two thousand people, unless I have some lines to read. But to stand up there just as Joe Clyde… whew.”

“Joe Clyde”… a curious phrase from the ’50s I used to hear in Baltimore. Meaning, of course, Joe Nobody. Indeed, Joe Clyde could be the collective self-image of the working class, the same class that scarfs up Eastwood’s pictures.

He smiles and explains how he made the transition from Joe Clyde to bit actor.

“I got drafted into the army. I was a swimming instructor at Fort Ord, California. It was a pretty good job, as far as keeping me off the front line, anyway. After I got out I came down here and went to Los Angeles City College on the GI Bill. I was twenty-three. This friend of mine was an editor, and he introduced me to a cinematographer, who made a film test of me just standing there—a shot here, a shot there—and Universal put me under contract at seventy-five dollars a week. I thought that was great stuff, but I was a little apprehensive. I mean, I didn’t know what it was going to be like when I had to start playing scenes in front of people. But I thought, what the hell, as long as they are paying… it was a hell of a lot more money than I would be making on the GI Bill. So I thought, ‘Well, I’ll just give it a good try. I’ll give it six months.’ But you can’t give it six months, ’cause nothing works out that quick. So what you do is you give it six, and then six more, and pretty soon it gets in your blood and you really want it.

“I kicked around there for a year and a half, but then they dropped their program and kicked me out, dropped my option. So then I did a lot of TV, both in New York and LA, and bounced around there. I was actually getting better parts in television than I was at Universal. But then I had a real slack period for a year or two.”

“When you were bouncing around, was there ever a sense of desperation? You know, ‘Christ, I’m not getting anywhere’…?”

“I’ll never forget,” Eastwood says with that Dirty Harry smirk. “I did a whole mess of shows for a year or so, then all of a sudden not much was happening around town, a lot of strikes and stuff, and I started collecting unemployment. But I couldn’t just do that, so I’d go and get jobs. I got a job digging swimming pools, and I’d be running back at my lunch hour and call my agent and ask, ‘What’s happening?’ And he’d say, ‘Nothing.’

“I finally got to a state where I was really depressed and I was going to quit. You know, I was married, no kids. But I got to do this one picture, a B movie, a little cheapo—did it in nine days, really a grind-out. It was called Ambush at Cimmaron Pass and I did it and forgot it. And then another slack period, no jobs, nothing, I hadn’t been employed for months. The movie finally came out and I went with my wife down to the little neighborhood theater, and it was soooo bad…. I just kept sinking lower and lower in my seat. I said to my wife, ‘I’m going to quit, I’m really going to quit. I gotta go back to school, I got to start doing something with my life.’ I was twenty-seven.”

“That’s the age you start to question yourself… moving toward thirty….”

“Yeah,” Clint says. “I was saying, ‘What am I doing here… spinning my wheels?’ and thinking this is the only profession in the world where there are three or four jobs and seven million people all want ’em, you know? The competition is really intense. You go into a producer’s office to audition for a part, and there are ten guys all sitting around, your size and your color. And you look at them like this…” Eastwood stares out of the side of his eyes, scared, flipped out, “…and you think, ‘There’s another one that’s going to go into the toilet.’” He stops and lets out a sigh.

“You have absolutely no control. It’s not like any other profession. If you’re a physician or something you can set up practice and work.”

“After a while you start thinking, ‘Well, I wonder if I’ll blow this one on the handshake.’ I started thinking I must be really bad because Wagon Train and all these other series were coming up, and I wouldn’t even be able to get in the front door. If l did get to meet the producer, the guy would give me a handshake, the dead stare, put the cigar out in the ashtray, and say, ‘Sure, we’ll get in touch with you, we’ll call your agent.’”

“That must have done a job on your spirits.”

“Oh…” Eastwood moans. “You have absolutely no control. It’s not like any other profession. If you’re a physician or something you can set up practice and work. It got so bad, I said, ‘I just can’t stand this anymore,’ knocking your head against the wall, coming up empty. I was never a particularly good salesman, either. I couldn’t go in and… like some other guys give the producer some good gags and a lot of hotshot stuff, and they’d get the parts. So I started thinking, ‘I’ve got to go back to school.’ I was thinking of all kinds of alternatives.”

“What were your alternatives?”

Eastwood smiles and sinks back into the couch. There has been a curious gentility to his recollections, as if he were retelling another life. The palpable silence behind his words, his laconic delivery, reveals a profound patience also visible in his film characterizations.

“That was the problem, I had never really figured any out. So I was visiting this friend of mine, she was a story reader for Studio One, Climax. And I was talking to her, just having a coffee or tea or something, and a guy walks over and says, ‘How tall are you?’ And I thought, why does he care how tall I am? But I said, ‘Well, six-six and I’m an actor,’ but I wasn’t very enthusiastic because I figured screw it, I’d had it. The guy says, ‘Well, could you come into my office for a second?’ and meanwhile my friend is behind me motioning, ‘Go, go!’

“It turns out he develops all the new shows for CBS. So I say, ‘Would you mind telling me what this is all about?’ and he says, ‘Well, this is a new, hour-long Western series’… because Wagon Train was a hit and they were all getting on the bandwagon I thought, ‘This could be something… but I was dressed about like this.” Eastwood points to his jeans, his two-hundred-dollar boots, and his blue Aztec T-shirt, “…a slob.

“All of a sudden I realize, ‘Hey, I’m playing this like it’s zero, I better sit up straight.’ So the guy says, ‘We’d like to talk to you and your agent.’ So I give him the number and I leave and the agent calls me when I get home and tells me to make a test tomorrow. I say, ‘Can I get to the scene ahead of time?’ and they say, ‘No scene, we’re just going to ask you questions.’ I thought, ‘Oh, hell, that’s the worst kind of test you can have.’ I never could read that well, I couldn’t read scripts out loud. If l knew the lines, I was fine, but I wasn’t a great reader.

“So I go down to make this test and the guy who interviewed me the day before is there and it turns out he’s the actor, the producer, everything. He says he has a scene for me to do. And there’s these other guys there, about four of them, and I’m thinking ‘One more cattle call, but maybe I can beat a few of these guys out.’ Anyway, this guy makes this huge speech to the camera, and I think, ‘Holy shit, there is no way I am going to learn this, no way in the world I am going to learn this dialogue.’ But there were three transitions in it, so I just picked out the three points I wanted to make and took out everything else.

“So I got up and came in, and I started going… and the guy is looking at me really strange. I was playing it rather well, at least I felt like I was… I was believing it, I thought. I did it again twice, and then I finished and he looked at me coldly and said, ‘Okay, we’ll call you.’ (I found out later he was a writer and he didn’t want the words tampered with.) So I go into the dressing room and take off this western costume, and as I’m leaving I hear this other guy doing it word-for-word, letter-for-letter, and I said, ‘Well, that’s the end of that.’ So I walked out and I wrote that one off.

“Then about a week later my agent called up and said, ‘Yeah, they want to use you!’ Well, ironically, the guy who projected all the tests for the wheels who came in from New York and LA was an old army buddy, and he told me that the wheels didn’t know what the dialogue was, and didn’t care. They were just looking at all of us, and what happened was that one of the wheels pointed at me and said, ‘That guy,’ and all the other little wheels said, ‘Yeah, that guy, that guy. I agree, J.R. He’s absolutely perfect.’ So I had a job. It was incredible.

“But there were a lot of stumbling blocks before it happened. We started making them, and it was really great—for ten straight weeks I had work. Then, after ten episodes, the word came down that we’re way over budget and behind schedule and we’re stopping it here at ten and ‘reevaluating our position.’”

Again, the Dirty Harry snicker. The notorious, fictional hatred of red tape comes into clearer focus.

“Then they said that hour shows aren’t going anymore, only half-hour shows. So they put all the shows on the shelf and they sat there for weeks. It was supposed to go on for the fall and it was cancelled for the fall, and I thought, ‘Oh, my God, my career is going to sit there on the shelf.’ I remember I was up for a part at Fox after that and I asked them if I could show one of the episodes. I had the lead in, and they said, ‘No, we don’t want to show it to anybody,’ and I thought, ‘My career is going to sit in the basement in tin cans at CBS.’

“Finally, I got on a train, just to go visit my parents, and I got a telegram on the train that it was going to replace some other show. And I didn’t know, we had so many false starts…. But the show jumped right into the top ten. It was a hit, and it was the first steady job I ever had.”

Eastwood smiles and sinks back into the couch. There has been a curious gentility to his recollections, as if he were retelling another life. The palpable silence behind his words, his laconic delivery, reveals a profound patience also visible in his film characterizations. We begin to discuss his step from TV to the movies.

“I had seen Yojimbo [a Japanese Samurai film] with a buddy of mine who was also a Western freak, and we both thought what a great Western it would make, but nobody would ever have the nerve, so we promptly forgot it. A few years later my agency calls up and says, ‘Would you like to go to Europe and make an Italian/Spanish/German coproduction, a Western version of a Japanese samurai story?’ and I said, ‘No, I’ve been doing a Western every week for six years, I’d love to hold out and get something else.’ And he said, ‘Would you read it anyway?’ so I read it and recognized it right away as Yojimbo. And it was good! The way the guy converted it had a tremendous amount of humor in it. So I thought, this looks like fun, it’ll probably go in the tank but at least it’ll be fun to do. The Italian producer thought it was going to be a nice little B programmer, but of course it went through the roof.”

“In Europe?”

“Yeah, they couldn’t release it in this country for a while because of a threatened injunction by the Japanese.”

“People liked to throw around the term ‘fascist.’ It didn’t bother me because I knew she was full of shit the whole time. She was writing to be controversial because people expect it of her, that’s how she made her name.”

“Because they thought it was a rip-off?”

“Well, it was a rip-off. The Italian producer had gone over to Japan to make negotiations, and when the fee the Japanese asked was too high, he just withdrew negotiations and went ahead and made it anyway.”

Eastwood laughs and shakes his head like a man who has early on learned to live with the absurd. His Man With No Name was called non-acting. In fact, his entire career has been called non-acting.

“They called me everything,” he says. “One critic wrote that I did nothing better than anyone who ever was on the screen, and there was a lot of name calling. It was that way with Dirty Harry, too.

Critic Pauline Kael called him a fascist. “That was just the style of the times,” he says deliberately. “People liked to throw around the term ‘fascist.’ It didn’t bother me because I knew she was full of shit the whole time. She was writing to be controversial because people expect it of her, that’s how she made her name. If Harry came out now, Kael would be onto something else. But the public liked the picture, and they realized it was just about a guy who was tired of the bureaucratic crap.”

“I get the impression you are more or less apolitical.”

“I don’t have any political thoughts. I feel like an individualist.”

“Your movies have been criticized as being anti-progressive,” I remind him, “or as advocating a kind of police state.”

“That isn’t the case,” Eastwood says firmly. “Anybody could see what the problems would be if the law enforcement agencies of any state were allowed to do anything they want. It would be dangerous. But the opposite is true: If you stifle the law, you invite getting bad people and corruption. It’s the opposite extreme.”

“But in the films themselves,” I continue, “like Dirty Harry… He says, ‘Screw all the red tape, I’m going to get the job done, bring these guys in’….”

“Yes, that was true in the first film. He wanted to get the job done. [Director Don] Siegel and I put ourselves in the victim’s standpoint; if I was a victim of a bizarre crime, I’d like to have someone with that kind of inspiration and imagination trying to solve the case. Sure it was an extreme case, but that doesn’t mean that Don Siegel or myself adhere to any kind of ultra-rightwing organization. In Magnum Force, we talked about just the opposite: if a rightwing group becomes the underground of the police force….”

Josey Wales lines up the Gatling gun. Below him are a hundred men, the scum responsible for the death of his wife. He squints, sets up the sight and begins to grind away. The men panic, scream, fall. Blood is gushing from their chest, arms, eyes. When he has run out of ammunition, Wales lopes away alone. He vows never again to become involved with any species of love. But there is this dog… a gangly, ugly, yellow dog… and it just won’t leave. Wales watches as the mongrel nears him. He waits until it is within range, then spits, Whack—a stream of tobacco juice slaps the mutt on the head. The dog whimpers, then disappears.

It is night now. Wales beds down in the brush and waits for what is left of the gang he has ambushed to come after him There is a noise, Wales jumps, whips out his gun. Something is moving toward him. He tenses, chews his tobacco, waits.

There is more movement. Then, around the bend, the dog is staring at him, unabashedly in love. Wales looks at it. His face softens. He grits his teeth. The dog comes toward him. Wales waits, then spits. Again, right on the head. The dog whimpers, moves away, but will not leave. Smoke rises from the fire, Wales watches the dog, stares at it, then shakes his head and goes to sleep.

Dogs and women. Eastwood, as prototype for monosyllabic movie machismo, has taken some vehement abuse for sexism in his films. It is a subject which he has obviously given some thought.

“When I did Play Misty for Me,” Eastwood says, “I took it to Universal, and the first thing they said to me was, ‘Why do you want to do a movie where the woman has the best part?’ Before that I had done The Beguiled, with six major parts for gals. I did Two Mules for Sister Sarah… a lot of movies with good women’s parts. I don’t consider myself sexist at all. I dig chicks probably as much as, if not more than, the next guy.”

There is an awkward pause.

“And you can probably call that sexist because I said ‘chicks,’ but I grew up where the guys in my neighborhood said that. The other day a female journalist asked me if I was intimidated by women, and I said, ‘No, I had a great relationship with my mother… I think she’s marvelous.”

“I never thought about being anything other than what I am. I put myself in a situation, learn the motivations of the character, and just go. If you started thinking about it, tried to play something like that, you’d come off like an idiot.”

“I’ve even heard that your movies are really gay fantasies,” I say.

Eastwood roars.

“People do put you down for macho quality,” I add.

“That’s getting back to those words again,” says Eastwood. “‘Fascist’ was the word before. Now it’s liable to be ‘macho.’ I never thought about being macho. I remember when I first came to Hollywood a director cold me, ‘Play this scene real ballsy,’ and I said to him, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about. I wouldn’t know how to do that.’

“I never thought about being anything other than what I am. I put myself in a situation, learn the motivations of the character, and just go. If you started thinking about it, tried to play something like that, you’d come off like an idiot. It would be caricature. If you think too much you can shut out things that work for you. So I really don’t think I’m sexist. Jessica Walters was very happy to have that role in Play Misty, and there was The Beguiled, and in The Gauntlet, Sondra Locke has, if not a better role, at least as good a role as me. I mean, she is the brains behind the whole thing.”

“But isn’t there a danger there? Your audience comes to Clint Eastwood films with certain expectations. The Man With No Name and Harry were both men in total control. Shockley, in The Gauntlet, is much more vulnerable. He’s an alcoholic, and not so smart. What’s more, he falls for the girl! I should think you’re treading on slippery ground here. The fans rebel, think you’re getting soft.”

Eastwood nods but doesn’t really address the problem:

“I guess there is a dyed-in-the-wool Dirty Harry fan who will be disappointed because I don’t grab a cannon and mow down everything in sight, but I think we can expand on the women’s parts. And in The Gauntlet, there’s still enough action to also satisfy the audience. It’s so hard to find really good stories and scripts. It’s amazing we could find three Dirty Harrys. I’d do another one, maybe, if we got a good script.”

Eastwood seems tentative here, and perhaps he should be. Though The Gauntlet started out well, its receipts are reportedly slipping.

Certainly it will not go in the tank, but it could turn out to be a financial disappointment.

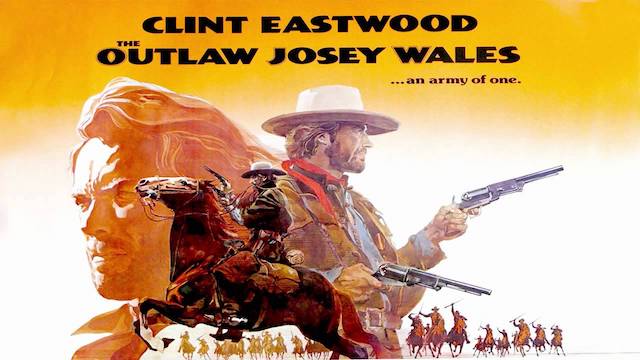

“Don’t forget Josey Wales,” says Eastwood. “It was different, warmer, and it was a box-office success.”

“And easily your best picture,” I agree.

“I’d never done that type of Western,” he says. “I’d always done allegorical things and I wanted to do a saga. And the humor in that wasn’t like in some of the others—total camp—it was warmer. Like with the dog—he spits on the dog, but he really wants him… yet he feels he brings bad luck on everybody.”

“He couldn’t speak English, and I couldn’t speak Italian, so we had an interpreter. But I could see he was a jovial guy with good feeling for black humor, so I figured it was going to be fun.”

Eastwood seems anxious to establish himself as the intelligent, civilized man he is. And although he is among the biggest stars in the world, he does seem to feel somewhat tarnished by the constant criticism. The increasing humanity in his films, and his vigorous, polite defense of himself, would seem to indicate he is trying gingerly to establish his full humanity, as an actor and a man.

“Many people who love your movies think they are either unintentional comedy or that the director makes them funny,” I say. “Many people assume you’re like Charles Bronson.”

“They should analyze Bronson’s movies,” Eastwood says curtly. “Are they funny?”

“No.”

“Well, then, how come my movies have that humor and his don’t?”

“Well, people assume that the director puts in the humor.”

“I’ve been the director on six of them,” Eastwood says. “Do you think it’s just by accident?”

“All right,” I say, “The Man With No Name in the Italian westerns. How did he happen?”

“Okay,” he begins, “I invented the costume, for example. I took it over with me, they just said, ‘Come on over.’ I went down to a costume store. I had one hat, three shirts, a sheepskin vest. I bought myself these black Levis, two sizes too big, and washed them. I wanted them to be kind of baggy. I didn’t want them to fit too well, I wanted everything to be just a little off. Only the shoes fit right. I had the boots, so I took those… took the boots and spurs…”

“Did you and [director] Sergio Leone create the character together?”

“Even Chaplin and the Tramp, he played those scenes very serious. Or Gleason and Carney in The Honeymooners, they weren’t sitting there talking to the audience, or the crew, or the backstage or anything. You gotta play the part and the camp will come out of it.”

“Well, he couldn’t speak English, and I couldn’t speak Italian, so we had an interpreter. But I could see he was a jovial guy with good feeling for black humor, so I figured it was going to be fun. The script had a lot more dialogue, I cut a lot of it out. To keep the mystique of the character it was very important not to have the guy say too much. Very important not to know his past. And the less you knew about him, the better. If you stop and give a big expository scene to explain everything that’s going on, audiences resent that. I think what you have to do is internalize the imagination of the audience, and then they’ll be right with you.”

“So you were aware then that the movie had a camp quality all the way through it.”

“Oh, yeah… it was a slight parody.”

“It was, and it wasn’t.”

“Yeah, but you still do it serious, you don’t wink. You see guys who do that, they’re winking at the camera all the time they’re up there, then the audience doesn’t believe that. They sit back and say, ‘Oh, yeah, we’re going to see Joe Slapstick here.’ Even Chaplin and the Tramp, he played those scenes very serious. Or Gleason and Carney in The Honeymooners, they weren’t sitting there talking to the audience, or the crew, or the backstage or anything. You gotta play the part and the camp will come out of it. And it took a lot… It takes a lot,” he emphasizes. “You light cigars, you spit on the dog’s head—it’s easy to crack, to do takes on it. But I don’t. It’s played absolutely serious. You’ve got to believe it, and the audience wants you to believe it. It’s not stand-up comedy.”

Frankly, I’m happy to hear this. And yet I wonder, “Why do people think you’re dumb?”

Eastwood sighs, shakes his head. “Because in an age of cynicism it’s easier to believe he’s just a big stupid guy standing there, doing these tricks and just accidentally pulling it off. I’m not the smartest guy in the world from a classic point of view, or an educational point of view—I don’t pretend to be any Rhodes scholar—but l do have animal instincts about things and I rely on them. Nobody, I don’t care who it is, is anywhere just being stupid.”

It’s been a rough day for Dirty Harry Callahan. He’s taken shit from just about everybody on the police force and on his beat. Finally, it’s lunch hour. Harry collapses at an outdoor chili parlor and orders up a hot dog and a Coke. He has just taken a bite and wiped the mustard from his mouth when he hears a commotion across the street. Slowly, like a wounded reptile, he turns. A bank is being robbed Harry watches with supreme disinterest, his eyes and facial muscles registering not a whit of disturbance. Around him, people are screaming as the armed robber makes his way out the door. Harry studies him. What’s all the commotion, ain’t no real problem here. Slowly, almost like a zombie, Harry finishes his hot dog, carefully wiping his mouth. Then, still chewing, he strolls across the street, knocks the thief’s gun to the street and places his own .44 Magnum at the base of the man’s skull.

“I’ve had a couple of fights already today, punk,” says Harry. “I’ve shot most of my bullets… maybe. Maybe I’ve got one left. You want to try your luck?”

The punk collapses on the ground. He looks longingly at his own gun, only a foot away. All he has to do is reach for it. But there are these snake’s eyes staring at him, and this huge barrel. Saliva forms on the edge of his mouth. He starts to reach out, then looks again at that death-mask face. You can see the life going out of him. Harry finishes chewing his hot dog and slowly, sadistically, licks his lips.

“I thought it would be interesting to have Harry not quite able to digest the hot dog, to keep right on eating it. Now, I don’t believe there’s a law officer in the world who would do that. It’s dumb, ridiculous. But I liked it, and I knew the audiences would like it. I mean, it’s funny!”

“It’s hilarious.”

“But it wasn’t in the script at the end, and I thought it would be great to have it come back in like an epilogue. Only that time there’s no hot dog. He plays it utterly straight. He’s getting this guy he’s gone out of his way to find, and he’s broken every rule, political and judicial, and it’s a sad moment, almost. Pauline Kael calls it a moment of glee when he shoots the guy, but there is no moment of glee. If she looked at it again I think she’d realize there’s actually a sadness about it. And when he drills the guy there’s no happiness, no smile.”

“She obviously wasn’t looking at the movie. She was looking at the last Robert Altman movie.”

Eastwood laughs and stretches out his frame. “There’s sadness in all of them,” he continues. “In The Enforcer, the girl is killed and he goes off alone. There’s a certain loneliness in all of them.”

“In the new one, though, he finds a girlfriend.”

“I wasn’t appalled by the violence in Taxi Driver because they went so overboard. Like, the guy holding his hand out so he could wait for his fingers to get shot off—I found myself laughing at that.”

“That’s right,” he says, “and not only a girlfriend, but one he wouldn’t respect. She’s a hooker and he’s a cop—two different kinds who would never respect one another but who can learn to. It’s more of an African Queen situation. It’s more of an old-fashioned movie. Look at It Happened One Night, how much reality is in that? But you enjoy the people—you enjoy the guy, you enjoy the gal. It’s entertainment.”

“But your movies are incredibly violent,” I say. “Do you worry about a carryover from screen violence to crime in the streets?”

“If that were the case,” Eastwood says, “then every guy on Death Row would have reason to be released because Tom Mix or James Cagney or Hoot Gibson shot guys on the screen. Or go back before movies to literature—Shakespeare, Greek tragedy—everybody can find some fall guy for why they commit some act of violence. You can say ‘My family insisted I learn about the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ.’ That’s a violent act where somebody is impaled on a cross.”

“Besides,” I agree, “there is a distinct difference between the violence in your movies and, say, Taxi Driver or The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, where you literally want to throw up.”

“Well, yeah,” he says, “except I wasn’t appalled by the violence in Taxi Driver because they went so overboard. Like, the guy holding his hand out so he could wait for his fingers to get shot off—I found myself laughing at that.”

Harry Callahan is standing in front of the mayor of San Francisco, a slick, beaver-faced man with grey ringlets drooping off his head. The Mayor Looks faintly like Nero. Harry looks like a slob. His herringbone tweed jacket is too small for him, his shirt is unbuttoned at the top, he has a big mouse under his eye where a psychopathic killer clipped him. Now, after almost being killed five times, Harry is being rewarded for his dedication by being taken off the case.

“I’m sorry, Callahan,” the Mayor says, “but you’ve broken the law. That’s what keeps the fabric of society together, you understand? No, you wouldn’t understand. Not your kind.”

“Somebody has to get him,” Harry spits.

“Not you, Callahan. You’re through. Now, get out.”

Harry looks around for support. From his chief, from the Mayor’s flunkies. Forget it. Slowly, with a profound torpor, he turns and moves toward the door.

“Asshole,” he mutters under his breath. “Assssshole.”

“Asshole” is to a Clint Eastwood film as “Rosebud” is to Citizen Kane. A signature, a recurrent coda. He always mutters it with a distinct nasal vehemence. I mention it and Eastwood roars.

“That’s my South Oakland background. I have college kids come up to me on the street and say, ‘Hey, man, say asshole the way you say it in the movies.’”

“Kind of a working-class talisman….”

Clint is really laughing and nodding now. “Oh, yeah. No matter how high you go, it’s something you never lose. I use it, because it was from my background, a certain way I got pissed. If Laurence Olivier tried that, it wouldn’t work at all.”

“No,” I laugh. “Perhaps ‘Ass-Hole: High Tea version.’”

Clint smiles again. “You don’t leave your background behind,” he says. “I’m the first in my family to ever make it. That’s one more reason I don’t play down to them; I came from that place. People know when you’re talking down to them. They instinctively know what’s going on…. All the good actors know this. Cagney, John Wayne, Gary Cooper…”

“I think if you analyze all the great actors of the past, it’s not what they did so much as what they might do, what they were about to do.”

“Were they your influences?”

“Cagney, especially. I loved that stuff.”

“Yet he was outgoing. With you there’s a kind of silence at the core of your characters. They’re slightly removed.”

“Well,” says Eastwood, “I think if you analyze all the great actors of the past, it’s not what they did so much as what they might do, what they were about to do. It wasn’t what they said—a lot of guys can do dialogue better than those guys. Charles Laughton was a great character actor and he had all sorts of tricks, but if he was on the screen with Gable, your attention was on Gable, even if Laughton was doing the talking.

“There’s a famous story. I can’t remember the character actor’s name, but he was talking about being onstage with Gary Cooper where he had this tremendous big monologue and Cooper didn’t say a word. And the character actor said he went to see the thing and he thought he had really wrapped the scene up, and he said when he got into theater he noticed that during his big monologue, everyone in the theater was staring at Cooper. And then he realized the worst part of all: he was staring at Cooper. That’s what real acting is all about.”

We both laugh and it’s time to go. Eastwood sees me to the door.

“Where will you go from here?” he says.

“Baltimore,” I say, grimacing a little.

“Yeah?” he says. “Do you get back to your old hometown often?”

“Not that often. And every time I do, my love-hate affair with the place surfaces and I end up kind of upset.”

Eastwood smiles and pats me on the back. “I know what you mean,” he says. “I feel that, too. But you never want to lose contact with it altogether.”

“I guess not,” I say, not quite sure.

“Nah,” says Eastwood. “You got to go back every now and then so you don’t forget how to say it.”

“Say what?” I ask.

With his best Dirty Harry smirk, Eastwood sneers: “Asshole.”

Postscript

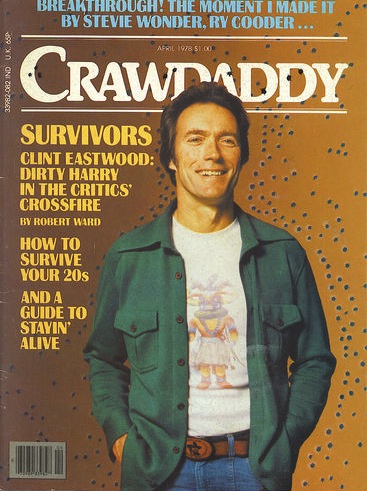

Clint Eastwood is now such an icon, and so beloved, that hardly anyone remembers the days when he was considered a handsome, stud-muffin with no brains. But as late as 1978 that’s exactly how most of the public and all the movie critics viewed him. Pauline Kael was the main culprit. She considered Dirty Harry a Fascist picture. She thought Eastwood was nothing more than a John Wayne, without talent.

It was very fashionable in those days to put Clint down, to laugh at his movies, his squint, and grimace. I laughed at him myself and made fun of his lack of acting chops with my cool, sophisticated friends.

The only thing wrong with my attitude was I’d never seen any of his pictures.

Finally, while visiting home in Baltimore, I went with a friend, the artist Scott McKenna, to the Towson Theatre to see The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. I expected nothing more than a campfest. We’d laugh at the horrible actor, make fun of the rotten Italian western, and go home feeling smug and superior.

Instead, Scott and I sat in our seats without so much as going to get popcorn or even take a piss for nearly three hours.

As we walked out in that special daze great movies put you in, I looked at Scott and said: “I think we’ve just seen one of the best movies of all time.”

Scott nodded, and we spent the rest of the night in a Towson lacrosse bar called The Crease going over the many great parts of the film. What we both agreed on was that: TGTBATU was one of the great movies, just a little behind The Wild Bunch in both our estimations. And that Clint Eastwood was a great actor. Pauline Kael didn’t know jackshit about acting or movies. Because Clint played the piece straight, which made movie work. Any hint of winking at the audience, or playing it for laughs would have ruined the whole delicate deal.

The movie was an epic western and an epic comedy, and an epic drama, and it all worked. Sergio Leone, whoever he was, was a genius. The guy who did the music—we didn’t know that his name was Ennio Morricone—was also amazing.

When I told my friends how much I loved Clint they laughed at me, and shook their heads. But I found, very quickly, that none of them had seen it.

It was sort of like discussing Moby Dick with writers. Everyone says it’s a masterpiece, no doubt. But when you try and discuss individual scenes with them they sort of change the subject. Why? Because no one ever finished it.

All I knew is that I felt Clint Eastwood was a great actor, and he deserved a serious interview. One in which he could answer his critics. So when editors Mitch Glazier and Tim White called me from Crawdaddy, and asked me to interview Clint I was more than ready.

I flew to Hollywood, and met Eastwood at his bungalow at Warner Brothers, and he couldn’t have been kinder and more open. I was told he never liked to talk and would only give people, at most, a half hour.

Instead, he gave me two hours.

I shook hands with him and left. I felt really excited. I had a great interview with the Man With No Name. I was so happy I decided to hear a little of it on my way to my rental car.

Then the worst happened, the reporter’s nightmare.

I had always hated tape recorders but more and more people told me they were invaluable, so I used a mini-tape recorder for the Eastwood interview.

I hit rewind, then play, and I heard… ZERO.

Nothing, nada, blip…

I felt my blood freeze. The guy who never gave interviews had liked me and given me two hours. Two hours to Crawdaddy, not exactly the New York Times or Rolling Stone. And now I was faced with going back to his bungalow and prostrating myself, begging him to do it all over again!

I tried to figure ways around it. Maybe I could remember everything he said. But for two hours? No way. I had no choice. I retraced my steps and went back to his office. I told his assistant what had happened. She looked at me like “Are you kidding me?” I wanted to crawl under her desk. I waited as she went into his office and told him.

Two minutes later he came out and looked at me, grimly.

I totally forgot that this was a professional situation and fully expected him to kill me.

That was fine. I wanted to die anyway. Just shoot me in the head so it’s quick, okay?

“Heard you had a little problem,” he said. In his low Dirty Harry voice.

“Uh, ah well you see I uh… hahaha…”

Clint smiled and opened the door into his office, the same office we’d just sat in for two hours.

“You have a cold,” he said. “You need another cookie and tea.”

And he did the whole interview, all two hours of it, over again.

To put it very simply, after that I loved the guy. I didn’t change one thing in the interview but as far as I’m concerned of all the giants I’ve met Clint stands out as one of the kindest.

I think too, that this interview was very brave. I asked him tough questions and often not flattering ones, like “Why do people think you’re stupid?” He answered them all reasonably and with a deep understanding of his craft.

I think that maybe this interview is the first time anyone saw how smart he really is, and how he might morph into the great actor/director he is today.

Clint Eastwood is a screen icon and also greatly admired as a director, particularly in the later part of his career. But in the mid-seventies he was seen by some as a right-wing stiff. Robert Ward—whose generous profiles of Robert Mitchum and Lee Marvin have previously appeared here—visited Eastwood during this time and delivers a candid and revealing look at the man behind the legend. The piece, complete with a postscript from the author, original appeared in the stellar compilation, Renegades, and appears here with permission from Robert Ward.—Alex Belth