Fame is fleeting in all pop culture—movies, music, writing, sports: today’s stars, tomorrow’s Where Are They Now’s. This feels especially true in journalism. Who but a small group of nonfiction-loving nerds pays attention to bylines anyway? We say, “Did you read that piece in the New Yorker last week?” more than we remember who wrote it. And hell, if movie stars don’t last in our consciousness what chance does an ink-stained wretch stand?

That’s what makes curating Esquire’s archives so much fun—foraging around and finding terrific stories by pros like Helen Lawrenson, Mark Jacobson, Elizabeth Kaye, and Lynn Darling. (Esquire Classic is a subscription site but non-subscribers can read 3 free stories each month.) This week we’ll shine a light on two steadfast practitioners of literary non-fiction—Thomas B. Morgan and Brock Brower. Neither were as famous as Tom Wolfe and Gay Talese, but Morgan and Brower led fascinating careers in their own right, laid the groundwork for the so-called New Journalism*, and left us with a trove of memorable portraits.

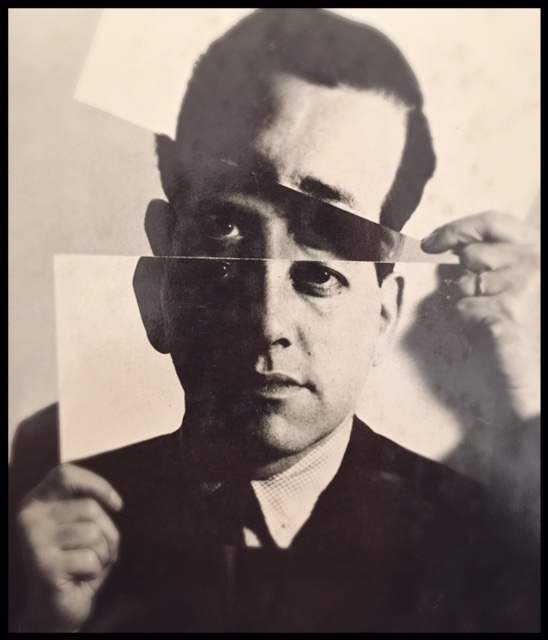

First up is Morgan. At six four he was an imposing figure, but spoke in what he once called “a disarming Corn Belt dialect” that seemed to put people at ease—“but never completely.” Morgan got his chops as a reporter and associate editor for Look and as a freelance writer, but by the mid-fifties he wasn’t happy and quit Look to write fiction. He pounded out two novels, neither of which were published until years later. When he finished the second one in the spring of 1957, Morgan had a celebratory lunch with Clay Felker, a smart young editor at Esquire. A casual conversation about Sammy Davis Jr. quickly turned into an assignment, and Morgan’s memorable 1959 profile, “What Makes Sammy Jr. Run?”

“Nobody had ever written serious pieces about entertainers at the time,” Morgan told Marc Weingarten in The Gang That Wouldn’t Write Straight. “I earned Sammy’s trust enough for him to open up to me about his life in a way that he hadn’t to any reporter.”

“Nobody had ever written serious pieces about entertainers at the time,” Morgan told Marc Weingarten in The Gang That Wouldn’t Write Straight. “I earned Sammy’s trust enough for him to open up to me about his life in a way that he hadn’t to any reporter.”

As Morgan wrote in the Introduction to his 1965 anthology of profiles, Self-Creation: 13 Impersonalities:

I began free-lancing for the magazines in order to live (I had become a father, twice) and discovered that a good thing had happened. The professional and the unclaimed novelist in me had resolved certain psychological differences. Why, I don’t know, but I had somehow assimilated attitudes related to fiction writing and these surfaced in my nonfiction pieces…I plan more novels, but I no longer tell myself that journalism is a preliminary before the main event.

This is the technique that was famously employed by New Journalist writers and it worked beautifully for Morgan in a series of profiles he contributed to Esquire in the early sixties.

“The Pleasures of Roy Cohn” (December, 1960)

“I have a basic sense of the unimportance of everything,” Cohn says. “You live seventy years. Civilization goes on after you’re gone, so what difference does it make?” He thinks about this for a moment; then he asks himself: “So why do anything? It’s all a matter of opportunities and desires, conscious and subconscious. You are propelled into certain things and you do them. I must like what I do or I wouldn’t do it. I have a choice of what I want to do.” This may be very contradictory, but it is Cohn. It sets him free to go on about his business and to take his opportunities as they come.

Cohn’s philosophy is, of course, a lonely one. It has neither ideology nor self-limiting purpose; it seems to exclude the idea of love. It could take a man in any direction—destructive or constructive— depending upon the circumstances. Its goal isn’t ultimately power or money, but the “doing” of things, of being on the telephone interminably. Cohn is a means man rather than an ends man. His real talent is for techniques and tactics and gambits; these are really his greatest pleasures. And to a degree, it is a reflex. Cohn has lived in an era that has placed a premium on technique, which is a function of conformity; the goal in his time has often been to play the game by whatever rules happen to be in effect. For the old Cohn, McCarthyism was the rules maker; for the new Cohn, the business-social world he inhabits. Prior to both, he seems to have been getting ready for any eventuality.

“The American Hero Grows Older” (May, 1961)

Gary Cooper’s Gary Cooper is second only to Charlie Chaplin’s tramp among all the enduring symbols created by U.S. movies. “When the critic of the American cinema looks around for the film that can give him his clue to American thought,” The Timesof London said unhappily recently, “he can point to nothing but the Western.” If one points to the Western, one must point at last to the archetype Gary Cooper. While Chaplin’s tramp expresses our common humanity and inevitable tragi-comedy, Cooper sums up the shifting American dream in terms of our national reluctance to grow older and our pioneer belief in the inevitable triumph of good over evil. On the screen, he is the essentially-simple-man who resolves complexities, finally, by taking matters into his own hands and simplifying them.

“…and Teddy” (April, 1962)

Thus played by Ted Kennedy, politics is a daily scrimmage, an unabashed, tightly organized, relentless competition against all comers. Going at it, he seems happy as a Boston clam. He is not unaware of certain shortcomings, wisdom yet to be gained, political experiences yet to be had. “What are my qualifications?” he asks. “What were Jack’s when he started?” But neither happiness nor humility should obscure the unfunny seriousness of his desire to win public office. He has no sense of the ridiculous, of his own as well as others’ essential folly. He seems to subscribe, without humor, to Mr. Dooley’s hollow dictum: “Politics ain’t bean bag.” If he has doubts, he keeps them to himself, relying on his ability to play the game using the equipment that was born and bred into him. For better or worse, he didn’t grow up absurd.

“God and Man in Hollywood” (May, 1963)

“God and Man in Hollywood” (May, 1963)

The [John] Wayne character is essentially a property for the movie business. “Wayne is awfully patriotic and we don’t always agree on social issues,” says Howard Hawks, who directed three of Wayne’s best-loved films, Red River, Rio Bravo, and Hatari!. “But he doesn’t ask that that stuff be put in. Wayne says, ‘Don’t tell me the story, Howard, tell me when you want me.’ On Rio Bravo, he said okay before he looked at the script. On the other hand, I use him a lot in testing whether he feels right doing a scene. He is a better actor than he is given credit for. Look, he has got the ability to play three or four good scenes and not offend the audience the rest of the time. What you get from Wayne is authority. He looks like he belongs in Western clothes. You also get a personality. I do not believe too much in actors playing parts. I believe in tailoring the part to the personality.”

“Blaze Starr In Nighttown” (July, 1964)

Blaze’s eyes lit up as she reminisced. She had loved Earl Long. She used to go on trips with him, handing out smoked hams and food baskets to back-bayou poor folks. Long’s enemies were scandalized, but Blaze blunted their needles with such public declarations as “I think that he is one of the finest men alive.”

…She went to the funeral with Debbie Star, José Martinez, manager of the Sho-Bar, and Polly Kavanaugh, another stripper. (In its reportage on the Governor’s last rites, the New Orleans TimesPicayune said, “An unexpected visitor was Blaze Starr, showgirl friend of Long.” In The Earl of Louisiana, A. J. Liebling corrected the impression created by this report: “I expect Long would have expected her . . . she had been on his side when a lot of the political mourners weren’t.”) She returned to the Two O’Clock Club four nights after the funeral. She was a celebrity now and Baltimoreans jammed the place. During the first show, just at the point where she shakes the rust out of her black pants, shouted from the banquette: “Hey, Blaze! How did old Earl look laid out in his casket?” The music stopped. “Shame on you,” Blaze said and finished her act. She returned to the dressing room, but Debbie Starr and Faye Harlow found the woman, dragged her from the banquette, and gave her a beating. “Down here in Baltimore,” Blaze said, “I’m not lying, they call us the Dalton Sisters. You know, we thought this woman would sue—and two weeks later, she did come in demanding to see me. I was waiting for her. I was going to, like, bust her in the mouth. But do you know, she apologized and honestly cried. She was really touching.”

For more from the Esky archives, check out Morgan on youth culture, “Teen-age Heroes: Mirrors of Muddled Youth” (March, 1960); literature, “The Autumnal Arrival of Lawrence Durrell” (September, 1960); publishing, “The Long Happy Life of Bennet Cerf” (March, 1964); politics, “Nelson Rockefeller: The Pitfalls of Personality Politics” (October, 1961), and “The Late Spring of Alf Landon” (October, 1962); civil rights, “Doom and Passion Along Rt. 45” (November, 1962); and show business, “David Suskind: Television’s Newest Spectacular” and “Presenting Darryl F. Zanuck’s War” (March, 1962).

Morgan eventually left magazines behind, and his distinguished career included stints as Mayor John Lindsay’s press secretary, editor of The Village Voice, heading up WNYC, and serving as president and chief executive of the United Nations Association of the U.S.A.

His writing for Esquire paved the way for Talese, Wolfe and the rest. Dig in and see for yourself—you’re in for a treat.

* From Tom Wolfe’s 1972 essay, “Why They Aren’t Writing the Great American Novel Anymore”:

I have no idea who coined the term “the New Journalism” or even when it was coined. Seymour Krim tells me that he first heard it used in 1965 when he was editor of Nugget and Pete Hamill called him and said he wanted to write an article called “The New Journalism” about people like Jimmy Breslin and Gay Talese. It was late in 1966 when you first started hearing people talk about “the New Journalism” in conversation, as best I can remember. I don’t know for sure…. To tell the truth, I’ve never even liked the term.

** From his second collection of criticism, The Good Word & Other Words, Wilfred Sheed summed up Wolfe’s 1973 anthology, The New Journalism, thusly—“All he has done is give literary glamor to some good journeymen reporters, and some journalistic glamor to the essayists, and provide some company of himself.” And more:

The worst news to come this way in some time (if you exclude the recent unpleasantness at the polls) is that Tom Wolfe is serious. I don’t mean artistically serious—I always assumed that—but, you know…serious. He has been carrying on at some length lately about his baby, the New Journalism, but with none of his old nerve-racking audacity. More like a…grandfather, for God’s sake.

This could have several dire consequences, even beyond the endless panel discussions it has already launched on “Is There a New Journalism,” all of which on Wolfe’s head. It has also robbed us of one of our most resourceful literary performers in the middle of his act: rather as if Groucho were to come back at Mrs. Rittenhouse with a lecture on comedy. That sort of thing should be postponed till dotage, at the very earliest.

[Photo Credit: Sol Mednick]