Jon Bradshaw always said he would die young, but he probably didn’t think he’d keel over on a public tennis court in Studio City a few weeks shy of turning forty-nine.

The smart money had said he’d meet his fate on assignment in the Comoro Islands, where he’d interviewed a French mercenary for Esquire. Or at the Komische Oper opera house in then East Berlin, in clandestine meetings with members of the Baader-Meinhof gang. Or in a prison cell in the ancient Indian city of Gwalior, where he was the first American journalist to interview Phoolan Devi, the murderous bandit queen. But not while playing doubles with friends one autumn morning in 1986 in the city of Angels.

“He was in it for the fun of it,” says writer-editor Lewis Lapham, “and for the learning. He delighted in the persona he presented but was not a self-promoter.”

Dying young fit the romantic image of the hard-drinking writer, and Bradshaw was a confirmed romantic who concocted his own literary persona: the magazine journalist as world-weary adventurer and dashing man-about-town.

In the 1960s, a handful of journalists such as Joan Didion, Jimmy Breslin, and Tom Wolfe emerged as literary rock stars. Magazines, then at the center of cultural conversation, delivered stories that were talked about for weeks, and for twenty years Bradshaw cut a distinct figure in this world, delivering controversial cover pieces and juicy character studies that were deftly written and intensively reported. Beginning in England at fashion magazines such as British Vogue and Queen, and then during his prime years at New York and Esquire, Bradshaw used the same novelistic devices of scene and dialogue that were the cornerstones of the New Journalism. But he was not associated with that or any other movement. His 1975 book about gambling, Fast Company, is justly considered a minor classic but Bradshaw never wrote a bestseller or had a story turned into a famous movie.

Letters to Bradshaw from Paul Bowles

“He was in it for the fun of it,” says writer-editor Lewis Lapham, “and for the learning. He delighted in the persona he presented but was not a self-promoter.”

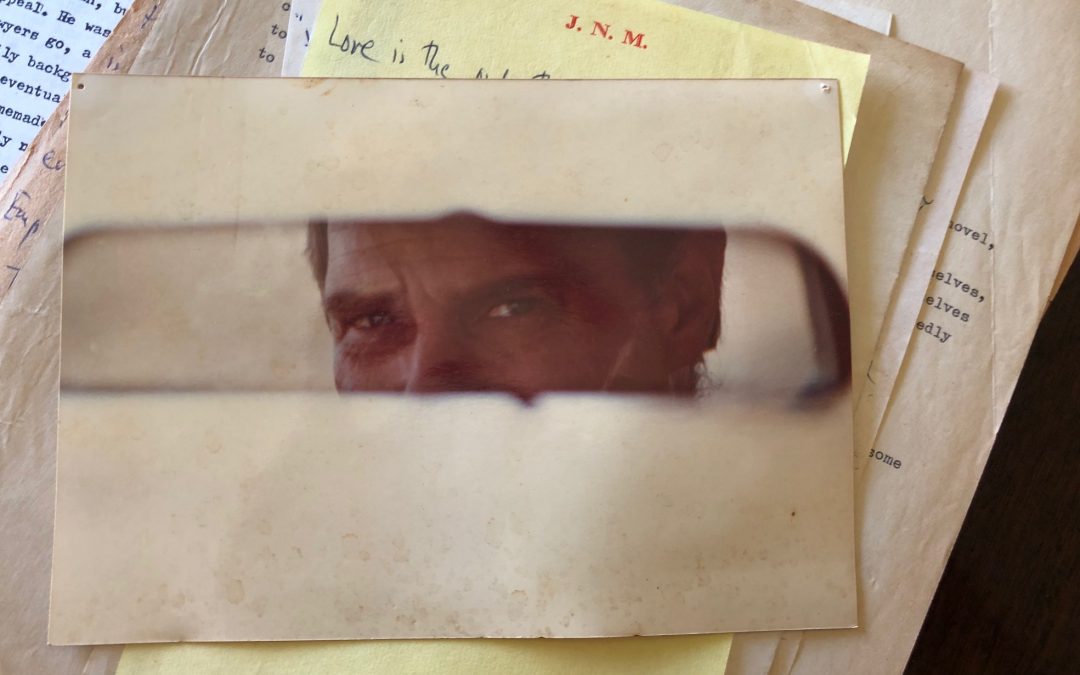

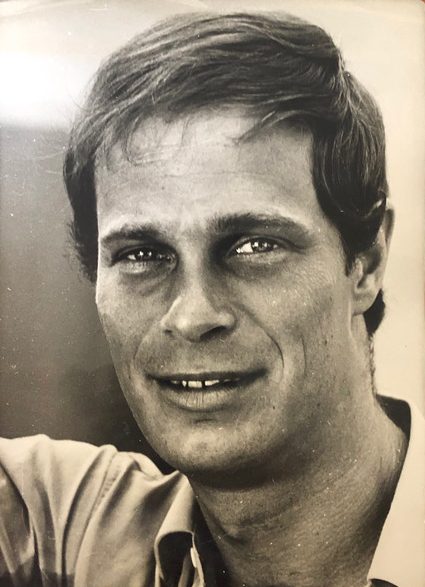

He was Bradshaw. Not Jon Bradshaw. Not Jonny or J.B. Just Bradshaw. Three packs of Rothmans a day, Johnnie Walker Black, two pieces of ice. Gambler, gossip, raconteur, playboy, and bon vivant, he fancied himself the last of the boulevardiers, “tripping the tightrope ’twixt insolence and insouciance,” as he’d say with a smile in his winsome, mischievous way. A toothless bulldog—all snarl, no bite—he forever looked like a man up to something. Handsome in a rugged 1930s movie star way and just this side of louche, Bradshaw was an American who adopted British manners and style without appearing effortful or ridiculous. Above all he possessed that elusive quality known as charm, which may seem a superficial talent, though one well suited to a reporter. It was a quality laced with magic, especially when he trained its lights on you.

“He was irresistible,” says Barbara Leary, a friend. “It was very hard not to be attracted to him. He certainly got people to be comfortable.”

“He was possibly the most social animal I ever knew,” says A. Scott Berg, the decorated biographer. “He loved being surrounded by boldface names in large measure because they loved having him in their company. I think the happiest night of his life that I witnessed was at a party at which Mick Jagger came over and talked to him for about an hour.”

“Bradshaw relished words,” recalls his friend John Byrne. “Given a new one he would swirl it in his mouth as if it were wine or bourbon.”

Bradshaw knew his worth and earned the drinks or the meal by flirting, cracking jokes, playing games—by being Bradshaw. Aristocrats, movie executives, and magazine editors wanted private audiences with him. Millionaires had him on their yachts for days just to play backgammon. “Part of his charm was that he was onto himself,” says writer Anne Taylor Fleming. “He was amused, and maybe even needy about his persona, but part of the reason he was beguiling is because it wasn’t a hard sell. There was a tenderness in Bradshaw. His charm wasn’t acquisitive or operational or manipulative.”

“Then he would sneak away to his typewriter, all affectation purged, and commence to write, cleanly and truthfully, enormously well,” his friend Nik Cohn wrote in 1986. “In all matters literary, no man could have been more devout. Indeed, his passions for propriety in language, precision in expression, were almost fetishistic.”

“Bradshaw relished words,” recalls his friend and occasional copy editor John Byrne. “Given a new one he would swirl it in his mouth as if it were wine or bourbon.” (It was Byrne who gave him “esurient”—a seventeenth-century word meaning “hungry, in a greedy way,” which shows up in Fast Company.) But Bradshaw’s love of words is not ostentatious, nor does it disrupt his otherwise unpretentious prose and keen observational eye. A New West feature about the Beverly Hills Hotel delivers a beaut: Penthouse publisher Bob Guccione by the pool one morning, sticking out among such suave record executives as Ahmet Ertegun and Clive Davis, “a piece of pork in a marmalade spread.”

Bradshaw wasn’t a memoirist or a propagandist. He wasn’t interested in shoving a point of view in the reader’s face. Weaned on Hemingway and Fitzgerald, influenced by the classics as well as such modern stylists as Nelson Algren, Evelyn Waugh, and Ian Fleming, Bradshaw writes in the understated magazine tradition of Lillian Ross and Gay Talese. We note his presence, but he recedes into the shadows so as not to get in the way of the story. Droll and deadpan, Bradshaw is an amiable, if booze-soaked guide.

Writing was hard work for him, and it took forever for Bradshaw to deliver a piece, deadlines be damned. Getting things right mattered, and Bradshaw paid for the grind of a freelance life mixed with much hard living. There was no camouflaging his blues during a late-night conversation with Berg in the fall of 1986, when the subject turned to death and funerals. “Here’s what I want at my memorial service,” Bradshaw said. He had it all outlined, where he wanted it held—Morton’s, a famous insider’s spot in Hollywood— as well as who should speak and in what order. This didn’t sound like some drunken riff. As soon as Berg got home, he wrote down everything he could remember.

A week later, Bradshaw was dead.

He had not joined the fitness revolution then sweeping the country. Booze, butts, heavy sauces, no salads. But he was competitive by nature, whether playing bridge, croquet, or Perquackey, and he wasn’t going to embarrass himself by not hustling.

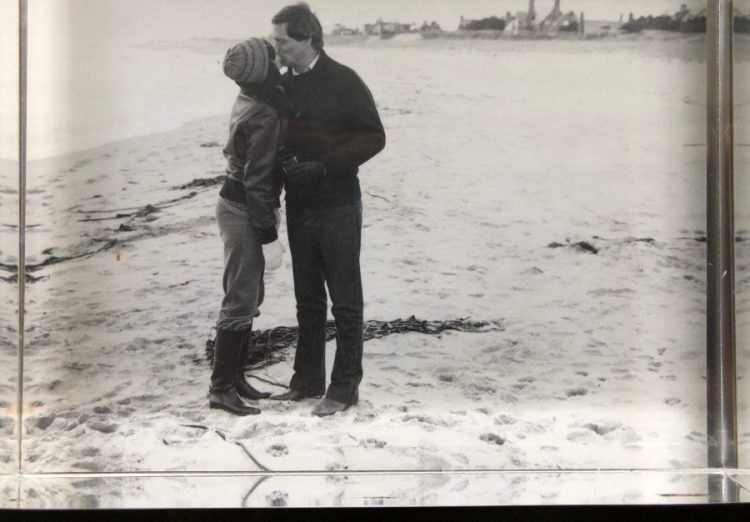

Bradshaw and his daughter Shannon by the ocean in San Diego less than a week before his death.

That’s what got him in trouble that day when he took the court with his pals Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais, the British comedy writing team, and photographer Eddie Sanderson. It didn’t take long before Bradshaw’s heart gave out. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, Bradshaw invoked his wife: “Carolyn will kill me for this,” he said, which is a pretty good line. Later, at UCLA Medical Center, his reported final words were: “Tennis will be the death of me yet.”

If that sounds too good to be true, you’re beginning to understand what made Bradshaw wink.

Jon Wayne Bradshaw spoke rarely of the past, and then only vaguely. “He wasn’t even awkward about it,” says Berg. “He just skipped right over it, as though he had sprung fully formed from the head of Zeus.”

We know that Bradshaw’s father took off when Jon was young, and his mother, Annis Murphy—“Murph” to her friends—sent Bradshaw and his younger brother, Jimmy, to Church Farm, a small boarding school for boys from single-parent homes in Exton, Pennsylvania. Bradshaw was on the milk squad, up at 4:30, tending to the cows before first period, and one in a graduating class of five. His mother, meanwhile, settled in Manhattan, where she worked as a copy editor at Vogue.

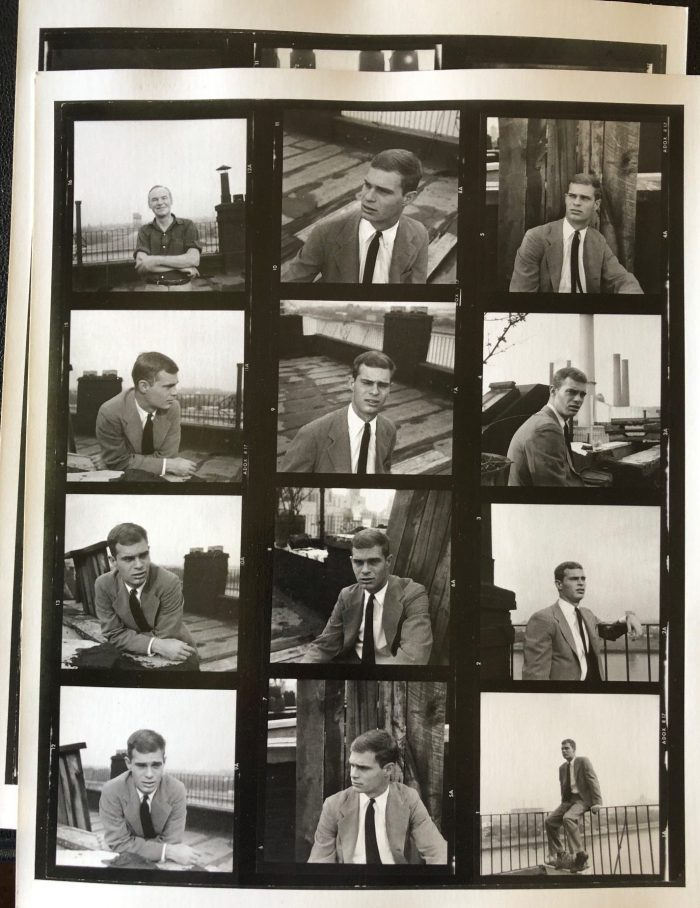

After high school, Bradshaw took a few college courses but sought his education the old-fashioned way. He drove and hitchhiked across America—sleeping in a field in Illinois, making stops in New Orleans and Salt Lake City, living for months in Portland, Oregon, where he wrote poetry and helped a friend build houses. He worked as a soda jerk and short-order cook, then moved back to New York, where he landed a job as a cub reporter for The Jersey Journal, followed by a four-month stint at the New York Herald Tribune. Already familiar with hangovers, romantic catastrophe, and sleeping on relatives’ sofas in Manhattan, he took off for England in 1963, which would be his home base for the next twelve years.

Bradshaw arrived in the nascent days of the Swinging Sixties and started as a reporter for the Daily Mail before shifting to the Sunday Times. Through his mother he was introduced to Anne Trehearne, fashion editor at Queen, an old society magazine then in the midst of a revival, and Beatrix Miller, the much-beloved editor of British Vogue. By the end of the decade, Bradshaw was a freelancer writing about restaurants and hot spots and spaghetti westerns, profiling the likes of John Osborne, Norman Mailer, Julie Christie, and the Beatles. But his favorite pieces were the travel features that took him to Monte Carlo, Pamplona, Trinidad, Haiti, and Jamaica.

“There just weren’t many people like Bradshaw,” says Anna Wintour, who went out with him for five years. “He stood out. He would walk into a room and own that room. Living in London and being American—which added to his aura. The polar opposite of the upper-class English world that I knew when I was growing up. He was not so polite and not so careful, wore jeans, had that great smile, and was just much more open. And yeah, a little bit dangerous. He caused a stir.”

When the Daily Telegraph sent him to Vietnam for a few months, Bradshaw turned up in Saigon in a brown velvet Carnaby Street suit. The other correspondents wore fatigues. “Well, here comes the correspondent from Vogue to cover the war,” said the New York Times Saigon bureau chief A. J. Langguth, who would become a lifelong friend.

Bradshaw did not yearn to be another David Halberstam or Michael Herr reporting from the front lines. He had no more interest in politics than in going to the moon. He rarely left Saigon and instead went drinking and whoring with Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, the Vietnamese prime minister.

“He was hopeless about money,” says Anna Wintour, “he was addicted to gambling, but everyone always forgave him because he was so funny and charming.”

Back in the UK, Bradshaw slid smoothly into high society. At Queen, he was often paired with photographer Lord Patrick Lichfield, first cousin to the Queen. Bradshaw and Lichfield were on assignment once and, when they arrived at the airport, were appalled to find they hadn’t been put in first class. This was Lord Lichfield, after all. They complained to no avail, then hit the bar before boarding. Once seated, Lichfield promptly fell asleep, and when he awoke he found Bradshaw’s seat next to him empty. Half an hour passed, no Bradshaw. Lichfield asked a flight attendant what happened to his friend. “Oh, that’s Lord Lichfield,” she said, “we’ve bumped him up to first.”

Bradshaw was less lucky in love. First came a misbegotten marriage to Ann Wace, the skyscraping daughter of the governor-general of Trinidad and Tobago. It lasted eight months, capped by an extravagant divorce party she threw for him in London. Shortly thereafter, Bradshaw began dating Wintour, the daughter of Charles Wintour, the esteemed editor of the Evening Standard.

“I was very young, and he was a larger-than-life figure,” says Wintour, who was twelve years his junior. “I think a lot of times I didn’t really understand what was going on. He was hopeless about money, he was addicted to gambling, but everyone always forgave him because he was so funny and charming.”

Wace and Wintour were unable to corral Bradshaw into respectability, or even get him to take his talent more seriously, but they never doubted he had it. “He was a voracious reader,” says Wintour. “He never lectured. I think he was always looking for himself in what he read.”

And in those he wrote about as well—from the poet W. H. Auden to Al Seitz, the streetwise proprietor of the Hotel Oloffson in Haiti, to the wily grifters profiled in Fast Company, a succès d’estime that Nik Cohn called “a personal, and seductive, work.”

Bradshaw returned to the States in 1975, as part of a “British invasion” of Clay Felker’s New York Magazine that included Cohn, reporter Anthony Haden-Guest, and illustrator Julian Allen. First at New York, and then at Esquire, Bradshaw enjoyed his most sustained professional success. At the same time, his relationship with Wintour fizzled. This might seem the part of our story where everything falls apart, but here’s a pleasant surprise: good fortune appeared in the form of Carolyn Pfeiffer, an old friend. They’d met years earlier as expats in the small London entertainment scene; now relocated to Los Angeles, Pfeiffer ran Alive Films and was an ideal partner.

“He once said to me that he was a nonperson until he married Carolyn,” says Leary. “He always credited Carolyn with getting him on the straight and narrow. I don’t know what direction he would have gone in had he not married her.”

“She’s much too good for me,” Bradshaw told another intimate.

Carolyn knew Bradshaw drank too much, but because he wasn’t a mean drunk, it was easy to overlook. “In many ways he was shy and insecure, and I think the drinking helped him to shore himself up,” she says. “I never remember thinking I lived with a depressed person, ever.”

She was more concerned with the cigarettes, but he didn’t have many sick days. “He was very self-motivating. For someone who’d take forever to write a piece, he was a busy bee around the house. It was great to live with him. He wasn’t the kind of man who left the top off the toothpaste.”

Bradshaw found himself in an unusual situation: domesticated. Although he put it down for not being literary enough, Bradshaw liked Los Angeles more than he cared to admit. Weirder still, he was now a father to a young daughter, Shannon, whom he adored.

Bradshaw spent most of this period laboring on a biography of Libby Holman, the torch singer and civil rights patron with a calamitous personal life, whom producer Ray Stark had suggested as a subject so that the book might be adapted into a movie. But drinks and conversation and laughter beckoned, all subversions of the discipline required to write a serious biography. Bradshaw was a sprinter, used to magazine deadlines. The Holman book, published in 1985, is a good, dutiful one, but it didn’t get rave reviews nor was it a bestseller.

Carolyn doesn’t remember Bradshaw morose, and neither do his friends. She was a little concerned about the pallor of his skin, but in the months leading up to his death, she was away on location. If you believe the body knows, perhaps mortality was on Bradshaw’s mind when he mapped out his memorial for Berg.

Bradshaw and Carolyn, early ’80s

Just as he desired, a memorial was held at Morton’s. Three more followed, including a regal affair gossip columnist Nigel Dempster organized in London and a well-attended send-off at Elaine’s, the famous literary saloon in New York. Finally, Carolyn and three-and-a-half year-old Shannon returned to their home in Jamaica, where they buried Bradshaw under a huge bougainvillea bush in the garden with about forty Jamaican friends in attendance. The event was officiated by the local Seventh-day Adventist minister, who arrived in a pickup truck with a boys choir in back. The toasts and stories lasted well into the night, and in many ways, it was the purest of the Bradshaw farewells.

“I am a great man, you know,” Berg recalls Bradshaw telling him. “Just look at who my friends are.”

Talking to many of them some thirty-five years later—a wondrous cocktail party of smart, lively conversationalists—is to understand how much they adored him in return.

The Ocean is Closed: Journalistic Adventures and Investigations is one of ZE Books unbelievably cool literary mix tape series. Check out the lot of them, here: