Dick Butkus slowly unraveled his mass from the confines of a white Toronado and walked into the Golden Ox Restaurant on Chicago’s North Side. He is built large and hard, big enough to make John Wayne look like his loyal sidekick. When he walks, he leads with his shoulders, and the slight forward hunch gives him an aura of barely restrained power. He always seems to be ready.

As he walked through the restaurant, he was recognized by most of the men sitting at lunch. But the expression on their faces was not the one of childlike surprise usually produced by celebrities. It was of frightened awe. It read: “Holy Christ! He really is an ape. He could tear me apart and he might love it.”

Ten rolling steps into the restaurant, with all eyes fixed on him, he was stopped by an ebullient lady with a thick German accent, a member of the staff. “Mr. Boot-kuss!” she scolded him. “What have you done to yourself? You look so thin.”

He smiled shyly. Not even the ferocious Dick Butkus can handle a rampant maternal instinct. “Aw,” he said. “I’m just down to my playing weight.”

Butkus chose a table in a far corner of the restaurant. It was a Friday afternoon, two days before the Chicago Bears were to meet the Minnesota Vikings in the first of two games the teams would play in 1970. The Vikings had won the NFL championship the year before and seemed likely to repeat. The Bears were presenting their usual combination of erratic offense and brutal defense and appeared to be on the verge of another undistinguished season. Butkus was joined at the table by a business associate and a journalist. He ordered a sandwich and a liter of dark beer. He doesn’t like journalists and is cautious to the point of hostility with them. But he fields the questions, because it’s part of his business.

“Do you think you can beat the Vikings?”

Butkus answers, “Yeah, the defense can beat them. I don’t know if the offense can score any points. But we can take it to those guys.”

“Have you ever been scared on a football field?”

“Scared?” he repeats, puzzled. “Of what?”

Then he smiles, knowing the effect he’s had on his questioner. “Just injuries,” he says. “That’s the only thing to be afraid of. I’m always hurt, never been healthy. If I ever felt really great and could play a hundred percent, shit, nobody’d know what was going on, it would be so amazing.”

“Does anybody play to intentionally hurt other guys?”

“Some assholes do. The really good ones don’t.”

“Dave Meggyesy, the ex-Cardinal, says that football is so brutal he was taught to use his hands to force a man’s cleats into the turf and then drive his shoulder into the man’s knee to rip his leg apart. That ever happen to you?”

“Hell, no! All you’d have to do is roll with the block and step on the guy’s face.”

That’s my man. Richard Marvin Butkus, 28 years old, 245 pounds, six feet, three inches tall, middle linebacker for the Chicago Bears football team, possibly the best man to ever play the position. To a fan, the story on Butkus is very simple. He’s the meanest, angriest, toughest, dirtiest son of a bitch in football. An animal, a savage, subhuman. But as good at his game as Ty Cobb was at his, or Don Budge at his, or Joe Louis at his.

As one of the Bear linemen said to me, “When you try to pick the best offensive guard, there are about five guys who are really close; it’s hard to pick one. The same thing’s true about most positions. But Butkus is the best. He’s superman. He’s the greatest thing since popcorn.”

The Minnesota game is being played on a warm, sunny autumn day at Chicago’s Wrigley Field before a capacity crowd. Both teams have come out to warm up, but Butkus is late, because his right knee is being shot up with cortisone. It was injured three weeks before in a game with the New York Giants. Butkus was caught from the blind side while moving sideways and the knee collapsed. Until then, the Giants had been playing away from him. When they realized he was hurt, they tried to play at him and he simply stuffed them. Giant quarterback Fran Tarkenton said afterward, “Butkus has the most concentration of any man in the game. He’s fantastic. And after he was hurt, he dragged that leg around the whole field. He was better after the injury than before—better on that one damn leg than with two.”

When Butkus finally comes out, his steps are hesitant, like he is trying to walk off a cramp. You notice immediately that he looks even bigger in pads and helmet—bigger than anyone else on the field, bigger than players listed in the program as outweighing him. He has the widest shoulders on earth. His name seems too small for him; the entire alphabet could be printed on the back of his uniform and there’d be room left over.

Both teams withdraw after warm-ups and the stadium announcer reads the line-ups. The biggest hand from the restless fans comes when Butkus’ name is announced. In the quiet that follows the applause, a raucous voice from high in the stands shouts, “Get Butkus’ ass.”

The players return to the field and string out along the side line. Both team benches at Wrigley Field are on the same side of the field, the Bears to the north and the Vikings to the south. Near midfield, opposing players and coaches stand quite close to each other, but there is almost no conversation between them, abusive or otherwise. As the Vikings arrange themselves for the national anthem, linebacker Wally Hilgenberg roars in on tight end John Beasley, a teammate, and delivers a series of resounding two-fisted hammer blows to Beasley’s shoulder pads, exhaling loud whoops as his fists land. Beasley then smashes Hilgenberg. Everyone is snarling and hissing as the seconds tick away before the kickoff. Butkus is one of the few who show no signs of nervousness. That is true off the field and on. He does not fidget nor pace. Mostly, he just stands rather loosely and stares.

After the anthem, the tempo on the sideline increases. The Bears will be kicking off. Howard Mudd, an offensive guard who was all-pro when the Bears obtained him in a trade from San Francisco, is screaming, “KICKOFF KICKOFF KICKOFF,” trying to get everyone else up as well as discharge some of his own energy. Mudd is a gap-toothed, blue-eyed 29-year-old with a bald spot at his crown who arrives at the field about 8:30 A.M.—fully four and a half hours before the game. He spends a lot of that time throwing up.

As I watch the Vikings’ first offensive series from the side line, the sense of space and precision that the fan gets, either up in the stadium or at home on television, is destroyed. The careful delineation of plays done by the TV experts becomes absurd. At ground level, all is mayhem; sophistication and artistry are destroyed by the sheer velocity of the game. Each snap of the ball sets off 21 crazed men dueling with one another for some kind of edge—the 22nd, the quarterback, is the only one trying to maintain calm and seek some sense of order in the asylum.

It’s the sudden, isolated noise that gets you. There is little sound just before each play begins—the crowd is usually quiet. At the snap, the tense vacuum is broken by sharp grunts and curses from the linemen as they slam into one another. The sudden smash of a forearm is sickening; and then there is the most chilling sound of all: the hollow thud as a launched, reckless body drives a shoulder pad into a ball carrier’s head—a sound more lonely and terrifying than a gunshot.

After receiving the kickoff, the Vikings are forced to punt when a third-down pass from Gary Cuozzo, the Viking quarterback, to Gene Washington falls incomplete. As the Bears come off the field, Butkus is screaming at left linebacker Doug Buffone and cornerback Joe Taylor, because Washington was open for the throw. Luckily, he dropped it. They are having a problem with the signals. There is something comical about Butkus screaming with his helmet on. His face is so large that it seems to be trying to get around the helmet, as if the face were stuffed into it against its will.

That third-down play was marked by a lapse in execution by both offense and defense. It was one of those plays when all the neatly drawn lines in the playbook are meaningless. The truth about football is that, rather than being a game of incredible precision, it is a game of breakdowns, of entropy. If all plays happened as conceived, it would be too easy a sport. But the reality is that the timing is usually destroyed by a mental error, by a misstep, by a defenseman getting a bigger piece of a man than he was expected to, by the mere pace of the action being beyond a man’s ability to think clearly when he’s under pressure. Or by his being belted in the neck and knee simultaneously while he’s supposed to be running nine steps down and four steps in.

The Bears don’t get anywhere against the Viking defense and Butkus is back out quickly. On the field, his presence is commanding. He doesn’t take a stance so much as install himself a few feet from the offensive center, screwing his heels down and hunching forward, hands on knees. His aura is total belligerence. As Cuozzo calls the signals, all of Butkus goes into motion. His mouth is usually calling signals of his own, his hands come off his knees, making preliminary pawing motions, and his legs begin to drive in place. No one in football has a better sense of where the ball will go, and Butkus moves instantly with the snap.

Two Cuozzo passes under pressure set up a Viking touchdown. On the Bears next set of offensive plays, they can’t get anything going, and the defense is back out. On the second play from scrimmage, the Vikings set up a perfect sweep, a play that looks great each time you put it on the blackboard but works right one time in ten. This is one of those times. Guards Milt Sunde and Ed White lead Clint Jones around the left side with no one in front of them except Butkus, who is moving over from his position in the middle. All four bodies are accelerating rapidly. The play happens right in front of me and Butkus launches himself around Sunde and smashes both forearms into White, clawing his way over the guard to bring Jones down for no gain. He has beaten three men.

The Vikings are forced to punt after that and the Bears get their first first down. Then, on first and ten, Bear quarterback Jack Concannon lobs a perfect pass to halfback Craig Baynham, who is open in the Viking secondary. Baynham drops it. And that is about as much as the Bear offense will show this day.

With 56 seconds left in the half, the Vikings have the ball again. Cuozzo is trapped in the backfield trying to pass; and as he sets to throw, the ball falls to the ground and the Bears pick it up. The officials rule that Cuozzo was in the act of throwing and therefore the Vikings maintain possession on an incomplete pass. The Bears and all of Wrigley Field think it’s a fumble and are expressing themselves accordingly. Butkus is enraged and is ranting at all the officials at once. But the Vikings keep the ball and a few seconds later try a field goal from the Bear 15. Butkus is stunting in the line, looking for a place to get through to block the kick. At the snap, he charges over tackle Ron Yary but is savagely triple-teamed and stopped. The field goal is good. When Yary comes off the field, he is bleeding heavily from the bridge of his nose but doesn’t seem to notice it.

As the half ends, a ruddy-looking gray-haired man who had been enthusiastically jeering the officials on the Cuozzo call slumps forward in his seat. Oxygen and a stretcher are dispatched immediately and the early diagnosis is a heart attack. He is rushed from the stadium, but the betting among the side-line spectators—an elite group of photographers, friends of the athletes and hangers-on—is that he won’t make it. They are right; the man is taken to a hospital and pronounced dead on arrival. A spectator, watching the game from behind a ground-level barricade, says, “If he had a season ticket, I’d like to buy it.”

The second half is more of the same for the Bears’ offense. Concannon throws another perfect touchdown pass, but it’s dropped; and the Vikings maintain their edge. The surprising thing is that the Bears never give up. With the score 24—0, the Bear offensive line is still hitting and, God knows, so is the defense. The Bears have a reputation as a physical team, and it’s justified. They have often given the impression, especially in the days when George Halas was coaching them, of being a bunch of guys who thought the best thing you could do on a Sunday afternoon was go out and kick a little ass. Winning was a possible but not necessary adjunct to playing football.

As Butkus comes off the field at the end of the third quarter, he’s limping noticeably, but it hasn’t affected his play. Cuozzo has had most of his success throwing short passes to the outside, but he continues to run plays in Butkus’ area. The plays begin to take on a hypnotic pattern for me. Every three downs or so, there is this paradigm running play: Tingelhoff, the center, charges at Butkus, who fends him off with his forearms. Then Butkus moves to the hole that Osborn or Brown has committed himself to. Butkus, legs driving, arms outstretched, seems to simply step forward and embrace the largest amount of space he can. And he smothers everything in it—an offensive lineman, possibly one of his own defensive linemen and the ball carrier. Then he simply hangs on and bulls it all to the ground.

“The first time I played against him, I was—well—almost disappointed. It wasn’t like hitting a wall or anything. He didn’t mess with me, he went by me. All he wants is the ball. When he gets to the ball carrier, he really rings that man’s bell.”

Finally, the game ends with a sense of stupefying boredom, because everyone seems to realize at once that there was never any hope. As the fans file out, one leans over a guardrail and screams at Bear head coach Jim Dooley, “Hey, Dooley! Whydoncha give Butkus a break? Trade him!” This is met with approval from his friends.

A few days after the Viking game, Butkus is in another North Side German restaurant. He is quiet, reserved and unhappy, because he feels that the Vikings didn’t show the Bears much, didn’t beat them physically nor with any great show of proficiency. I can’t help thinking that a man of his talent would get tired of this kind of second-rate football.

“Don’t you ever get bored? Don’t you think of retiring from this grind?”

“No way!”

“But what do you get from it? It’s got to be very frustrating. Why do you play?”

“Hell. That’s like asking a guy why he fucks.”

The following Sunday, the Bears are flat and lose badly to an amazing passing display from the San Diego Chargers. But they have been pointing toward their next big game—a rematch with an old and hated rival, the Detroit Lions. Earlier in the year, on national television, the Bears led the Lions for a half but ended up losing. After that game, Lion head coach Joe Schmidt said that his middle linebacker, Mike Lucci, was the best in football and that Butkus was overrated. The Lions generally said that Butkus was dirty rather than good. It added a little spice to a game that didn’t need any.

The question of linebacking is an interesting one to consider. To play that position, a man must be strong enough in the arms and shoulders to fight off offensive linemen who often outweigh him, fast enough to cover receivers coming out of the backfield and rangy enough to move laterally with speed. But the real key to the position is an instantaneous ferocity—the ability to burst rather than run. And the man must function in the face of offenses that have been specifically designed to influence his actions away from the ball. Butkus is regarded as the strongest of middle linebackers, the very best at stopping running plays.

I once asked Howard Mudd if the 49ers, his previous team, had a special game plan for Butkus. “Sure,” he said. “The plan was to not run between the tackles: always ensure that you block Dick. Once the game started, the plan changed, though. It became, ‘Don’t run. Just pass.’”

Mudd also pointed out something that belies Butkus’ reputation for viciousness. “He doesn’t try to punish the blockers.” Mudd said. “He doesn’t hit you in the head, like a lot of guys. The first time I played against him, I was—well—almost disappointed. It wasn’t like hitting a wall or anything. He didn’t mess with me, he went by me. All he wants is the ball. When he gets to the ball carrier, he really rings that man’s bell.”

In the Bear defense, Butkus is responsible for calling the signals and for smelling out the ball. If he has a weakness, it’s that he sometimes seems to wallow a bit on his pass drops, allowing a man to catch a pass in front of him and assuming that the force of his tackle will have an effect on the man’s confidence. It often does.

The night before the Lions game, Butkus was at his home in a suburb about 40 minute drive from Wrigley Field. It’s an attractive ranch-style brick house. In front of the garage is a white pickup truck with the initials D.B. unobtrusively hand-lettered on the door. Inside the garage is a motorcycle. These are Butkus’ toys. The main floor of the house is charmingly furnished and reflects the taste of his wife, Helen, an attractive auburn-haired woman who is expecting their third child early in 1971. She is a lively but reserved woman who runs the domestic side of their lives and attempts to keep track of Nikki, a four-year-old girl, and Ricky, a three-year-old boy—two golden-haired and rugged children.

The basement of the house belongs mostly to Butkus. Its finished, paneled area contains a covered pool table—he doesn’t enjoy the game very much nor play it well—and a bar. Along the walls are as many trophies and glory photos as a man could ever hope for. The only photograph he calls to a visitor’s attention is an evocative one from Sports Illustrated that shows him in profile, looking grimy and tired, draining the contents of a soft-drink cup.

At the far end of the basement is Butkus’ workroom. The area is dominated by a large apparatus of steel posts and appendages that looks like some futuristic torture chamber. It’s called a Universal Gym and its various protrusions allow him to exercise every part of his body. There is other exercise equipment about and in a far corner is a sauna. Butkus works out regularly but not to build strength. His objective is to keep his weight down and his muscles loose.

After an early dinner with the family, Butkus secluded himself in the bedroom with his playbooks and 16mm projector for a last look at the Lions’ offense in its shadowy screen incarnation. Just after ten o’clock, he went to sleep. He woke early the next morning and went to early Mass, at 6:30, so that he didn’t have to dress up. He and the priest were the only ones there. He returned home to eat a big steak and, after breakfast, he spent some more time with the playbooks. About ten o’clock he left the house for the drive to the ball park.

“He’s real quiet before a game,” Mrs. Butkus says, “but he’s usually quiet. When he was dating me, my mother used to ask, ‘Can’t he talk?’ I don’t think he gets nervous before a game. I think it’s just anticipation. He really wants to get at them.”

She is remarkably cheerful about football and likes to talk about her husband’s prowess. Her favorite story is one that she learned when she met Fuzzy Thurston, one of the great offensive linemen from Vince Lombardi’s years at Green Bay. “Fuzzy told me,” she says, “that when Dick played against the Packers the first time, Lombardi growled, ‘Let’s smear this kid’s face.’ But Fuzzy says they just couldn’t touch him. After the game, Lombardi said, ‘He’s the best who ever played the position.’”

The day of the Lions game is cool and clear. When Butkus comes out, his expression is blank. The Bears are quieter and more fidgety than before the Viking game. It’s immediately apparent that this game will be played at a higher pitch than the previous ones, nearly off the scale that measures human rage. People who play football and who write about it like to talk about finesse, about a lineman’s “moves.” But when the game is really on, the finesse gets very basic. The shoulder dip and slip is replaced by the clenched fist to the head, the forearm chop to the knee and the helmet in the face.

From the opening play, the fans show they are in a wild mood. They have begun to call Mike Lucci (pronounced Loo-chee) Lucy. And when Lucci is on the field, they taunt him mercilessly. “Hey, Lucy! You’re not big enough to carry Butkus’ shoes.”

The Lions are stopped on their first offensive series, and punt. As the ball sails downfield, Butkus and Ed Flanagan, the Detroit center, trade punches at midfield. They are both completely out of the play.

Soon enough, the Bear defense is back out. Butkus seems to be in a frenzy. He stunts constantly, pointing, shouting, trying to rattle Lion quarterback Bill Munson. On first down at the Lions’ 20. he stuns Flanagan, who is trying to block him, with his forearm and knifes through on the left side to bring down Mel Farr for a five-yard loss.

On second down, Munson hands off to Farr going to his left. The left tackle, Roger Shoals, has gotten position on defensive end Ed O’Bradovich, as Farr cuts to the side line. Butkus, coming from the middle, lunges around the upright Shoals-O’Bradovich combination like a snake slithering around a tree and slashes at the runner’s knees with his outstretched forearm. Farr crumbles.

On third down, Munson tries to pass to Altie Taylor in front of right linebacker Lee Roy Caffey. Caffey cocks his arm to ram it down Taylor’s throat as he catches the ball, but Taylor drops the pass and Caffey relaxes the arm and pats him on the helmet.

The Lions set to punt and Butkus lurches up and down the line, looking for a gap. He finds one and gets a piece of the ball with his hand. The punt is short and the Bears have good position at midfield. On the first play from scrimmage, Concannon drops back and drills a pass to Dick Gordon, who has gotten behind two defenders. Gordon goes in standing up for a touchdown and pandemonium takes over Wrigley Field.

The game settles down a bit after that and the only other score for a while is a Lion field goal. Munson is trying to get a running game going to the outside, but Butkus is having an incredible day. He is getting outside as fast as Farr and Taylor. The runner and Butkus are in some strange pas de deux. Both seem to move to the same place at the same time, the runner driving fiercely with his legs, trying to set his blocks and find daylight. Butkus seems, by comparison, oddly graceful, his legs taking long lateral strides, his arms outstretched, fending off would-be blockers. But it’s all happening at dervish speed and each impact has a jarring effect on the runner. Lucci, when he’s on the field, just doesn’t dominate the action and is taking abuse from the fans. He’s neither as strong nor as quick. He’s good on the pass drops, possibly better than Butkus, but he’s not the same kind of destructive tackler.

Midway in the second quarter, Detroit cornerback Dick LeBeau intercepts a Concannon pass intended for Gordon. Gordon had gone inside and Concannon had thrown outside. Entropy again. The half ends with the score 7-3, Bears. On the side line after the half-time break, the Bears are back at high pitch. Concannon is yelling, “Go, defense,” and Abe Gibron, the Bears’ defensive coach, is offering, “Hit ‘em to hurt ’em!” A wide man of medium height, Gibron was an all-pro tackle for many years in pro football’s earlier era. He is a coach in the Lombardi mold, full of venom and fire—abusive to foe and friend. He is sometimes comical to watch as he walks the side line hurling imprecations for the entire football game; but his defenses are solid and brutal.

The intensity of the hitting seems to be increasing. Butkus makes successive resounding tackles, once on Farr and once on Taylor. He does not tackle so much as explode his shoulder into a man, as if he were trying to drive him under the ground. The effect is enhanced by his preference for hitting high, for getting as big a piece as he can. Butkus once told a television sports announcer, “I sometimes have a dream where I hit a man so hard his head pops off and rolls downfield.” On a third-down play, Munson passes deep and Butkus, far downfield, breaks up the pass with his hand. The fans are overjoyed and have a few choice things to say about Lucci’s parentage.

The Bears get the ball, but Concannon is intercepted again and the defense gets ready to go back in. As Butkus and the others stand tensely on the side line, it’s clear to everyone that they are Chicago’s only chance to win; the offense is just too sluggish. The “D’s,” as they are called, have all the charisma on this team, and as they prepare to guts it out some more, I am overcome by a strange emotion. Stoop-shouldered and sunken-chested, weighing all of 177 pounds rather meagerly spread over a six-foot, three-inch frame, I want to join them. Not merely want but feel compelled to go out there and get my shoulder in—smash my body against the invaders. At this moment, those 11 men—frustrated, mean and near exhaustion—are the only possibility for gallantry and heroism that I know. The urge to be out there wells up in me the way it does in a kid reacting to a field sergeant who asks for the impossible—because to not volunteer involves a potential loss of manhood that is too great to face.

The defenses dominate the game for a while, but a short Bear punt gives the Lions good position and they get a field goal. A bit later, Munson passes for a touchdown and the Lions take the lead, 13-7. The Lions were favored in the betting before the game by as much as 16 points, and after the touchdown, the side-liners are murmuring things like, “I’m still all right, I got thirteen and a half.”

With four minutes left in the game and the score 16-10 after each team has added a field goal, coach Dooley pulls Concannon in favor of the younger, less experienced but strong-armed Bobby Douglass, his second-string quarterback. A clumsy hand-off on a fourth and one convinced Dooley that Concannon was tired, although Concannon will indicate afterward that he wasn’t. Pulling him at this point in the game, when the Bears obviously have only one chance to score and when a touchdown and point after would win, is an unusual thing to do, and Concannon is upset. He is a dark, scraggly-haired Irishman, very high strung, a ballplayer who stares at the fans when they’re abusing him. He never feigns indifference. Now he is standing on the side line, head slightly bowed, pawing the ground with his cleats while someone else runs his team. His hands are firmly thrust into his warm-up jacket and all the time he stands there, intently watching the game, he repeats venomously over and over, “Stuff ’em! Stuff ‘em! Fuck you, Lions! Goddamn it! Goddamn it! Fuck you, Lions!”

Douglass doesn’t move the team and the Lions take over. Gibron is screaming that there’s plenty of time. There is one minute, 36 seconds on the clock. Altie Taylor gets a crucial, time-consuming first down. Butkus tackles him viciously from behind, nearly bisecting him with his helmet; but the Bears are losers again.

His speech is filled with the nasal sounds of Chicago’s Far South Side, and he is very much a neighborhood kid grown up. His tastes are simple—in food, in entertainment, in people. He doesn’t run with a fast crowd.

The Bear defense had played tough football, and Butkus had played a great game. I said as much to him and he replied, “Hell, we’re just losin’ games again. It don’t matter what else happened.” But he didn’t deny the ferocity of the Bear defense: “You didn’t see a lot of that second effort out there,” he said, referring to the Lion backs. “They weren’t running as hard as they might.”

“Do you think you intimidated them?”

“They knew they were getting hit. And when you know you’re getting in there, then you really lay it on them.”

“What was the reason for the punches with Flanagan?”

“I wanted to let him know he was going to be in a game.”

Butkus seemed to talk all the time on the field. Was he calling signals to his own players or yelling at Detroit?

“Mostly it’s signals for our side, but every once in a while, I’ll say something to jag them a little.”

“Like what?”

“Oh, you know. Call them a bunch of faggots or somethin’. Or I told sixty-three after a play when I got around him that he threw a horseshit block.”

Butkus says these things in an emotionless voice—almost shrugging the words out rather than speaking them. His speech is filled with the nasal sounds of Chicago’s Far South Side, and he is very much a neighborhood kid grown up. His tastes are simple—in food, in entertainment, in people. He doesn’t run with a fast crowd. If you ask him what he does for kicks, he shrugs, “I don’t know, just goof around, I guess.” He has wanted to play football all his life, and one of his most disarming and embarrassing statements when he was graduated from college was. “I came here to play football. I knew they weren’t going to make a genius out of me.”

As a kid, Butkus loved to play baseball. Surprisingly, he couldn’t hit but had all the other skills. He pitched, caught and played the infield. He had the grace of a “good little man,” and that may be one key to his success. Unlike most big football players, who find it hard to walk and whistle at the same time, and have to be taught how to get around the field, Butkus has the moves of a quick, slippery small man who happens to have grown to 245 pounds.

By the time he got to high school, Butkus was committed to football. His high school coach wouldn’t let him scrimmage in practice for fear that the overenthusiastic Butkus would hurt some of the kids on his own team.

He distrusts worldliness in most forms, except that he knows that his stardom can make money and he works at it. He has changed his hair style from the crewcut he wore in his early years to something a bit longer, but he’s far from shaggy. His clothes are without style. He wears open-collar shirts, shapeless slacks and button-front cardigan sweaters that he never buttons. A floppy, unlined tan raincoat is his one concession to Chicago winters.

He is genuinely shy and deferential on all matters except football, and his façade is quiet cynicism. He especially dislikes bravado and gung-hoism when he has reason to believe they’re false, as he does with many of the Bear offensive players. Although he has a reputation for grimness, he smiles rather easily. And his laugh is a genuine surprise; it’s a small boy’s giggle, thoroughly disconcerting in his huge frame.

His shyness comes out in odd ways. When asked if, as defensive captain, he ever chews out another player for a missed assignment, he says, “Nah. Who am I to tell somebody else that he isn’t doing the job? After all, maybe I’m not doing my job so good.” Butkus is serious.

That sort of resignation makes him an ideal employee—sometimes to his own detriment. Butkus thinks, for example, that his original contract with the Bears was for too little money—and he’s been suffering financially ever since. But he refuses to consider holding out for a renegotiation or playing out his contract option in order to get a better deal with a new team. “I made my mistake,” he says. “Now I gotta live with it.” And, although you probably couldn’t find a coach in the world who wouldn’t trade his next dozen draft choices for him, Butkus thinks that if he did something so downright daring as leave the Bears, no other team would take him, because he’d have marked himself a renegade.

This is not so much naїveté on Butkus’ part as it is a deeply conservative strain in the man. When he saw a quote from Alex Johnson, the troubled California Angels baseball player, suggesting that he wanted to be treated like a human being, not like an athlete, Butkus said, “Hell, if he doesn’t want to be treated like an athlete, let him go work the line in a steel mill. Ask those guys if they’re treated like human beings.”

Yet Butkus is not a company man. If anything, he is brutally cynical about established authorities—especially the management of the Chicago Bears football club—but he abhors being in a position where he finds himself personally exposed, and distrusts anyone who would willingly place himself in that position.

He especially dislikes personal contact with the fans. He complains about being stared at and being interrupted in restaurants. He is also inclined to moan about the ephemeral nature of his career. “It could be over any time,” he says. “An injury could do it tomorrow. And even if I stay healthy, hell, it’s all gonna be over in ten years.” I ask if he has any plans for the future. “Not as a hanger-on, trying to live off my name. When it’s over, I’m gonna hang up the fifty-one and get out. I’m not gonna fool around as some comedian or public speaker.”

For the present, Butkus determinedly, but with no joy, does as much off-field promotional activity as he can get. He attends awards dinners and other ceremonial functions and will appear at just about any sports-related event that comes along. He’s done some television appearances and made one delightful commercial for Rise shaving cream. This year, International Merchandising Corporation (the president of I.M.C., Mark McCormack, is the man who merchandised Arnold Palmer, among others) contacted Butkus and now manages his finances. His name has begun to appear on an assortment of sports gear and may yet make its way to hair dressings and other such men’s items. When I told Butkus that he had taken his place in the pantheon of great middle linebackers, along with Sam Huff and Ray Nitschke, he said, “Hell, I’m going to make more money this year than those guys ever thought about.”

Over the following six weeks, the Bears played a lot of mediocre football; they won two, lost four—although two of those were very close.

The next time I saw Butkus was on a cold, damp Thursday—a practice day for the Bears’ return match with the Packers. The numbing grayness of the Chicago winter day was matched only by the Bears’ mood at practice. They were sluggish and disconnected and seemed to be going through motions to run out the string. The Packer game was the next-to-last one of the season. Butkus was working with the defense under coaches Gibron and Don Shinnick. Shinnick is the Bears’ linebacker coach and a veteran of 13 years with the Baltimore Colts. He is an enthusiastic, straightforward man who doesn’t hassle his players. He is Butkus’ favorite coach, and the impression you get from talking to either of them is that they both think that Don Shinnick and Dick Butkus are the only two men in the world qualified to talk about football.

The defense was working on its pass coverage against some second-string receivers. Doug Buffone was bitching to Shinnick because they weren’t practicing against the first string and couldn’t get their timing right. They had practiced with the first string before their Baltimore game and Buffone said that it was directly responsible for five interceptions in the game. Shinnick agreed but gave Buffone an “I don’t make the rules” look and they both went back to the drill.

Gibron was installing some new formations to defend against Green Bay. One was called Duck and the other Cora. They tried out some plays to see if everyone could pick up Butkus’ signal. Butkus called “Duck” if he wanted one formation in the backfield and “Cora” for another and they relayed it to one another. Gibron was unhappy with the rhythm and said, “Listen. Don’t say ‘Duck.’ It could be ‘fuck’ or ‘suck’ or anything. Say ‘Quack quack’ instead, OK?” For the next few minutes, the Bears shouted “Quack quack” as loud as they could. Butkus just stared at Gibron. Then they ran some patterns.

Shortly, the defense left the field so Concannon and the first-string receivers could work out without interference. Butkus stood morosely on the side line with Ed O’Bradovich, the only team member he is really close to.

O.B., as he is called, is a huge curly-haired man endowed with a nonchalant grace and good humor. He looks like he’s never shown concern for anything, especially his own safety.

A visitor at the practice says to Butkus. “That quack-quack stuff sounds pretty good.”

“It’s not quack quack,” says Butkus, glowering. “It’s Duck.”

Butkus is about two weeks into a mustache. “It’s for one of those Mexican cowboy movies,” he says.

O’Bradovich says, “You’re gonna look like an overgrown Mexican faggot.”

“Yeah, who’s gonna tell me?” At that minute, a burst of sharp, raucous howling rises up where the offensive linemen are working on their pass blocking. “Look at ’em,” Butkus says. “Let’s see how much noise they make against Green Bay on Sunday.”

As I look around the practice field, there seems to be chaos among the players. If I were a betting man, I’d go very heavy against the Bears. They seem totally dispirited. “It’s all horseshit,” Butkus says. “Everybody wants it to be over.”

Just before the practice breaks up, coach Dooley calls everyone together and says, “All right! Now, we’ve had these three good practices this week. And we’re ready. Let’s do a big job out here Sunday.” All the players leave after a muffled shout—except for Concannon, who runs some laps, and Mac Percival, the place kicker, who has been waiting for a clear field to practice on. One of the coaches holds for Percival, and as I head for the stands, Percival makes nine field goals in a row from the 36-yard line before missing one.

Sunday is sunny, but three previous days of rain have left the side lines muddy, although the field itself is in good shape. The air is damp and cold; it’s a day when the fingers and toes go numb quickly and the rest of the body follows. Bear-Packer games are usually brutal affairs, but this game is meaningless in terms of divisional standings: both teams are out of contention. There is speculation, however, that each head coach—Phil Bengtson of the Packers and Dooley of the Bears—has his job on the line and that the one who loses the game will also lose his job.

When the line-ups for the game are announced, the biggest hand is not for Butkus but for Bart Starr, Green Bay’s legendary quarterback. If Butkus is the symbol of the game’s ferocity, then Starr is the symbol of its potential for innocence and glory. He is the third-string quarterback who made good—Lombardi’s quarterback—an uncanny incarnation of skill, resourcefulness, dedication and humility. He is the Decent American, a man of restraint and self-discipline who would be tough only in the face of a tough job. But he is so much in awe of the game he plays that he wept unashamedly after scoring the winning touchdown in Green Bay’s last-second victory over Dallas in minus-13-degree weather for the NFL championship in 1967.

The Packers receive and on the first two plays from scrimmage, Butkus bangs first Donny Anderson, then Dave Hampton to the ground. He has come out ferocious. A third-down play fails and the Packers punt. On the Bears’ first play from scrimmage, Concannon throws a screen pass to running back Don Shy, who scampers 64 yards to the Packer 15. Concannon completes a pass to George Farmer and then throws a short touchdown pass to Dick Gordon. Bears lead, 7-0.

Green Bay’s ball: Starr hands off to Hampton, who slips before he gets to the line of scrimmage. On second and ten, Butkus stunts a bit, then gets an angle inside as Starr goes back to pass. Butkus gets through untouched and slams Starr for an eight-yard loss. The Packers are stopped again, and punt. As Starr comes off the field, he heads for the man with the headset on to find out from the rooftop spotters just what the hell is going on.

On the Bears’ next offensive play, Concannon drops back and arcs a pass to Farmer, who has gotten behind Bob Jeter. Touchdown. Bears lead, 14-0, and there is ecstasy in the air. It is a complete turnaround and my shock at the Bears today—after watching them on Thursday—is testimony to how difficult sports clichés are to overcome. I am obsessed with whether the team is up or down, as if that were the essence of the game. Actually, for all anyone knows, the Packers might have come to Wrigley Field “up” out of their minds. It doesn’t matter. The Bears are just good this day; they are at a peak of physical skill as well as emotional drive. Concannon is very close to his finest potential and, for all it matters, might be depressed emotionally. What counts is that his passes are perhaps an eighth of an inch truer as he loops his arm, and that is enough to touch greatness.

All the Bears are teeing off from their heels. When the game began, Bob Brown, the Packers’ best pass rusher, sneered at Jim Cadile, Bear guard, the man across the line from him, “I’m gonna kill you.”

Cadile drawled, “I’ll be here all day.” The Packers now have the ball, third down, on their own 19. Starr drops back to pass and, with no open receiver, starts to run the ball himself. As he gets to the line of scrimmage, he is tripped up with four Bears closing in on him, one of whom is Butkus. I’m watching the play from the side line right behind Starr. From that vantage point Butkus, looking for a piece of Starr, is all helmet and shoulders brutally launched. The piece of Starr that Butkus gets is his head. Starr lies on the ground as the Packer trainer comes to his aid. The crowd noise is deafening.

Starr is helped from the field and immediately examined by the team physician, who checks his eyes to see if there are signs of concussion. The doctor leaves him and Starr, who looks frail at six feet, one inch, 190 pounds in the land of giants, puts his helmet on and says that he’s all right. When the Bears are stopped on a drive and punt, he returns and immediately goes to work completing some short, perfectly timed passes. He moves the Packers to the Bear 15. Then, on second down, he is smashed trying to pass and comes off the field again. He is replaced by a rookie named Frank Patrick, who can’t get anything going, and the Packers kick a field goal. Starr is now seated on the bench, head in hands, sniffing smelling salts. He’s out for the day.

The game turns into a blood-lust orgy for the Bears. O’Bradovich is playing across from offensive tackle Francis Peay. Vince Lombardi had obtained Peay from the New York Giants, predicting that the tackle was going to be one of the greats, and he is good, indeed. But on this day, O’Bradovich is looming very large in Peay’s life. In fact, he is kicking the shit out of him, actually hurling Peay’s body out of his way each time Patrick tries to set up to pass. The Packer rookie is in the worst possible position for an inexperienced quarterback. He has to pass and the defense knows it. The linemen don’t have to protect against the running game and just keep on coming.

Lee Roy Caffey had been traded to Chicago by the Packers. After each set of violent exhibitions by the Bear defense, he comes off the field right in front of Packer coach Bengtson, screaming, “You motherfucker. You traded me! And we’re gonna kill you!”

One of the most impressive pass plays of the game comes in the second quarter, with the score 14-3 and the Bears driving. Concannon throws a short high pass down the side line that George Farmer has to go high in the air to catch. Farmer seems to hang for a moment, as if the football has been nailed in place and his body were suspended from it. In that vulnerable position, Ray Nitschke, the Packers’ middle linebacker, crashes him with a rolling tackle that swings Farmer’s body like a pendulum. As Farmer turns horizontal, still in the air, Willie Wood, the safety, crushes him and Farmer bounces on the ground. But he holds onto the football.

A few plays later, Concannon, looking for a receiver at the Packer 25-yard line, finds no one open and runs in for a touchdown. It is a day when he can do no wrong.

The hysteria on the field even works its way up to the usually cool stadium announcer. In the third quarter, when Dick Gordon beats Doug Hart for another touchdown pass from Concannon, the announcer, with his mike behind his back, screams in livid rage at the Packer defender, “You’re shit, Hart! You’re shit!” Then he puts the instrument to his mouth and announces to the fans in his best oratorical voice, “Concannon’s pass complete to Gordon. Touchdown Bears.”

At the Packer bench, Bart Starr is spending the day with his head bowed, pawing the turf with his cleats. It occurs to me that every quarterback I have watched this year has spent a lot of his time in that position: Concannon, Munson, Unitas when the Bears were leading Baltimore, and now Starr.

Behind Starr, Ray Nitschke has just come off the field after the Bear touchdown. Nitschke is one of the great figures from Green Bay’s irrepressible teams of the Sixties, and his face looks like he gave up any claims on the sanctity of his body when he decided to play football. He is gnarled, bald and has lost his front teeth. He constantly flexes his face muscles, opening and clamping his jaw in a set of grotesque expressions. He has put on a long Packer cape and is prowling the side line, exhaling plumes of vapor from his nostrils, the cape flowing gracefully behind him. There is something sublime in the image. Nitschke is the caped crusader; had there ever really been a Batman, he could not have been a pretty-boy millionaire—he’d have been this gnarled avenger.

As the game progresses further in the third quarter, the hysteria increases and it’s hard to follow the play sequences or the score, and little details intrude on my mind:

• Little Cecil Turner, the swift black return specialist, running back a kickoff after the Packers score a touchdown, is finding daylight. As he works his way up-field, a black Packer screams to his teammates on the field, “Kill that dude!”

• O’Bradovich, coming off the field after hurling Peay around some more, sits down with his sleeves rolled up in a spot where he can avoid the heat from the side-line blowers—on a day when it’s so cold that a man standing next to me is warming his hands over the open flame of his cigarette lighter.

• Willie Holman, Bear defensive tackle, barrels into Patrick as he tries to pass. The ball has no speed and is intercepted. Holman’s shot actually rings in the ears for a moment. That night on the TV reruns, you can’t even tell that Holman caused the interception, because there is no sound, no sense of the brutality of the play.

• Butkus is dumped on his ass by Gale Gillingham as he tries to blitz Patrick. Gillingham is one of the very good offensive guards around and it’s an incredible shot. The only time I’ve seen Butkus go backward all year.

• Jim Ringo, the nine-year all-pro center who now coaches the Bear offensive line, winces with pain each time a Bear defensive lineman wipes out one of Green Bay’s offensive linemen. It’s obvious that Ringo simply hates all defensive players, even his own.

Late in the fourth quarter, with the game safely out of reach, 35-10, Butkus comes out and is replaced by John Neidert. Gibron and the defense are now very much interested in the game again. The Packers, get a little drive going and are at the Bear 13. Neidert is getting a lot of information from the Bear bench, especially from Gibron. To show some respect for the rule that prohibits coaching from the side line while the clock is running, Gibron wants to call his signals discreetly. He is trying to whisper “Double-zone ax” across a distance of some 25 yards.

Double zone means that the corner-backs will play the wide receivers tight, one on one. Ax means that the middle linebacker will take the tight end alone on the short drop. On the next play, Patrick completes a pass to the tight end for the score. As Neidert comes off the field, he is heartbroken and Gibron is screaming, “Neidert, whatsamatta wit-choo? If you don’t know it, say so. Did you have the ax in?” Neidert, who looks too confused to think, only nods and kneels down, looking as if he is close to tears. It’s possible that at the end of this already decided football game, on a meaningless score, his football career might be over. It’s the one upsetting thought in an otherwise brilliant day for the Bears.

Two months after the Packer game, after a trip to Los Angeles to play in the Pro Bowl, Butkus goes into the hospital, to have his knee operated on. He leaves the hospital afterward but suffers great pain for days and finally returns to see if anything can be done about it. Butkus thinks a muscle was strained when the cast was put on; the doctor doesn’t agree and can’t understand why he is having so much pain. I went to visit Butkus at Illinois Masonic Hospital, a typically ugly yellow-walled institution. When I get to his room, he is playing gin rummy with a friend and is in a very scowly mood.

He doesn’t look like a typical patient. He isn’t wearing a hospital gown, just a pair of shorts, and his upper body is almost wider than the bed. The impression is that any moment he may get out of bed, pick it up as if it were an attaché case and walk out. He offers me a beer from a large container filled with ice and cans.

He gets bored with the rummy game very quickly and his guest departs.

“How do you feel?”

“Horseshit.”

Butkus describes the pain he’s been having in the side of his knee and tells me the doctor just keeps saying that Gale Sayers was up and around the day after his knee was operated on. He isn’t happy with the doctor. His wife, who is nine months pregnant, enters. We all discuss the pain for a minute and she makes it clear that she thinks it may be partly psychosomatic.

Butkus talks about a condominium he’s bought on Marco Island in Florida and a big Kawasaki bike that he hasn’t been able to ride because of the operation. He is very uncomfortable and we get into some more beers.

I ask if he was trying to hurt Starr in the Green Bay game. “Nah,” he says. “I just went in there with everybody else. That’s what you gotta do. But you should see the mail from Wisconsin. I got a letter that said, ‘You shouldn’t hit old people.’ Another one said, ‘I hope you get yours.’”

Butkus continually reaches down to massage his leg, which is wrapped from hip to toe in a bandage. A nurse comes in with a paper cup containing an assortment of brightly colored capsules. He asks which one is the painkiller, but the nurse refuses to tell him. She explains that he has been taking a number of sedatives since his arrival in the hospital and Butkus is disturbed that he’s been swallowing a lot of stuff that hasn’t done any good. “We didn’t want to give you anything too strong,” she tells him archly. “We thought you were taking care of yourself with the beer.” It is apparent that a lot of people are enjoying the fact that the big, mean Butkus is acting like a six-year-old. He looks at the nurse with puzzlement and annoyance. He doesn’t think that any of this is the least bit funny and goes back to rubbing his knee.

“Do you think the operation is going to make you cautious?”

“No. But nobody’s going to hit this knee again. No way.”

During the next few weeks, the knee continued to trouble him. He had an unusual reaction to the catgut that had been used to rebuild the joint and his body was trying to reject it. He was often in pain and became adept at squeezing pus and sometimes chunks of catgut from the suppurating incision. At the end of March, the doctor opened the knee again and cleaned it out. This time, the doctor and Butkus were satisfied and a second operation, planned to rebuild the other side of the knee, was canceled because the joint seemed sound again.

Early in April. Butkus went to Florida to relax. He returned to Chicago after a brief stay and fell into an off-season pattern. Fool with the Kawasaki, have beers with O’Bradovich, spend Sundays with his family. In late May, he started to tune his body on the Universal Gym.

On a hot, rainy morning last June, I arrived at Butkus’ house to find him sitting in the kitchen jouncing Matthew Butkus, who had been born in late February (8 pounds, 13 ounces), on his knee. The father was cooing and the son was grinning, as well he should, considering that he was spending much of his first few months surrounded by the protective comfort of those huge hands.

Butkus was still unsure of the knee. “I think I’ll really be able to go on it around December first,” he said. That would mean missing three months of the season. I didn’t know if he was serious, and it occurred to me that he didn’t either. He was to see the doctor that afternoon. I had an appointment to visit his parents, who live nearby, and as I left, his wife said, “If that knee isn’t OK, I’m moving South. He’ll be impossible to live with.”

Butkus’ parents are Lithuanian. They have seven children (Dick is the youngest and smallest of five boys) and 22 grandchildren; the family is loyal and gathers frequently.

When I got to the house, Mr. Butkus, 80 years old, a bushy-browed, weathered man of medium height was working with a spade on the grounds. The rain had stopped and the day had turned sunny and hot. He was calmly digging out weeds in a small thicket bordering an expansive lawn that fronted the house. A white-plaster statue sat in the middle of the lawn. Mr. Butkus is a friendly man of few words who has little to say about his youngest son’s success. It’s simply not something that he relates to easily. The senior Mrs. Butkus is quite another story. She’s a big woman who clearly supplied her sons’ breadth of shoulder and chest. She is a bit immobilized now from a recent fall and thoroughly fills the armchair she is seated in. Butkus bought the house for his parents a few years ago. The living room is filled with the furniture and remnants of other places and times, and the harsh early-afternoon light seems to be cooled by its journey around the knickknacks to the corner of the room, where she is sitting. His mother says of Dick: “He didn’t make any special trouble. He liked practical jokes a lot but never got into any real trouble. He was full of mischief and energy—like any other boy.” There is something hard in her attitude, something that comes from raising a lot of children. Life is not wonderful, not too simple, but it’s not too bad, either. It’s to be endured—and sometimes bullied. As she stares out the window, thinking about Dick, she says, “When he was a kid, his brothers would take him to the College All-Star game. He’d sit there and say, ‘I’m going to play here. This is where I’m going.’” She pauses, and then continues: “You know, his brother Ronnie played for a while with the old Chicago Cardinals. He had to stop because of a knee injury.” Then she turns to me and says, “I hope Dick gets well. It’s his life.”

This story is collected in Football: Great Writing about the National Sport.

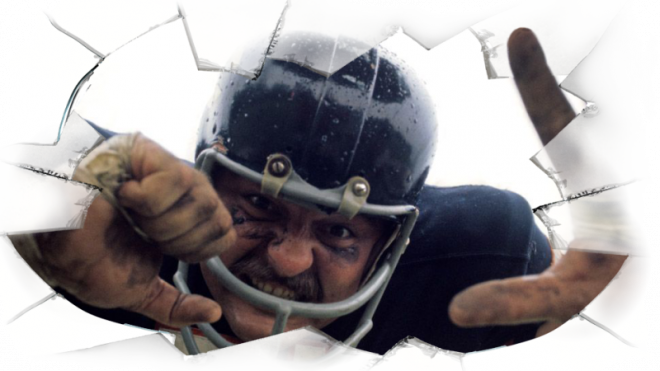

[Featured Illustration Jim Cooke; source photo by Richard Fegley for Playboy.]