Stanley Ketchel was twenty-four years old when he was fatally shot in the back by the common-law husband of the lady who was cooking his breakfast.

That was in 1910. Up to 1907 the world at large had never heard of Ketchel. In the three years between his first fame and his murder, he made an impression on the public mind such as few men before or after him have made. When he died, he was already a folk hero and a legend. At once, his friends, followers, and biographers began to speak of his squalid end, not as a shooting or a killing, but as an assassination — as though Ketchel were Lincoln. The thought is blasphemous, maybe, but not entirely cockeyed. The crude, brawling, low-living, wild-eyed, sentimental, dissipated, almost illiterate hobo, who broke every Commandment at his disposal, had this in common with a handful of presidents, generals, athletes, and soul-savers, as well as with fabled characters like Paul Bunyan and Johnny Appleseed: he was the stuff of myth. He entered mythology at a younger age than most of the others, and he still holds stoutly to his place there.

There’s a story by Ernest Hemingway, “The Light of the World,” in which a couple of boys on the road sit listening to a pair of seedy harlots as they trade lies about how they loved the late Steve Ketchel in person. This is the mythology of the hustler — the shiniest lie the girls can manage, the invocation of the top name in the folklore of sporting life. Ketchel is also an article of barroom faith. Francis Albertanti, a boxing press agent, likes to tell about the fight fan who was spitting beer and adulation at Mickey Walker one night in a saloon soon after Mickey had won a big fight.

“Kid,” said the fan to Walker, “you’re the greatest middleweight that ever came down the road. The greatest. And don’t let anybody tell you different.”

“What about Ketchel?” said Albertanti in the background, stirring up trouble.

“Ketchel?” screamed the barfly, galvanized by the name. He grabbed Walker’s coat. “Listen, bum!” he said to Walker. “You couldn’t lick one side of Steve Ketchel on the best day you ever saw!”

Thousands of stories have been told about Ketchel. As befits a figure of myth, they are half truth — at best — and half lies. He was lied about in his lifetime by those who knew him best, including himself. Ketchel had a lurid pulp-fiction writer’s mind. He loved the clichés of melodrama. His own story of his life, as he told it to Nat Fleischer, his official biographer, is full of naïve trimmings about bullies twice his size whom he licked as a boy, about people who saved him from certain death in his youth and whom he later visited in a limousine to repay a hundredfold. These tall tales weren’t necessary. The truth was strong enough. Ketchel was champion of the world, perhaps the best fist fighter of his weight in history, a genuine wild man in private life, a legitimate all-around meteor, who needed no faking of his passport to legend. But he couldn’t resist stringing his saga with tinsel. And it’s something more than coincidence that his three closest friends toward the end of his life were three of the greatest Munchausens in America: Willus Britt, a fight manager; Wilson Mizner, a wit and literary con man; and Hype Igoe, a romantic journalist.T hey are all dead now. In their time, they juiced up Ketchel’s imagination, and he juiced up theirs.

Mizner, who managed Ketchel for a short time, would tell of a day when he went looking for the fighter and found him in bed, smoking opium, with a blonde and a brunette. Well, the story is possible. It has often been said that Ketchel smoked hop, and he knew brunettes by the carload, and blondes by the platoon. But it’s more likely that Mizner manufactured the tale to hang one of his own lines on: “What did I do?” he would say. “What could I do? I told them to move over.”

Ketchel had the same effect on Willus Britt’s fictional impulse. When Britt, Mizner’s predecessor as manager, brought Ketchel east for the first time from California, where he won his fame, he couldn’t help gilding the lily. Willus put him in chaps and spurs and billed him as a cowboy. Ketchel was never a cowboy, though he would have loved to have been one. He was a semi-retired hobo (even after he had money, he sometimes rode the rods from choice) and an ex-bouncer of lushes in a bagnio.

“He had the soul of a bouncer,” says Dumb Dan Morgan, one of the few surviving boxing men who knew him well, “but a bouncer who enjoyed the work.”

His friends called him Steve. He won the world’s middleweight championship in California at the age of twenty-one. He lost it to Billy Papke by a knockout and won it back by a knockout. He was a champion when he died by the gun.

One of Bill Mizner’s best bons mots was the one he uttered when he heard of Ketchel’s death: “Tell ’em to start counting to ten, and he’ll get up.” Ketchel would have lapped it up. He would have liked even better such things as Igoe used to write after Ketchel’s murder — “the assassin’s bullet that sent Steve down into the great purple valley.” The great purple valley was to Ketchel’s taste. It would have made him weep. He wept when he saw a painting, on a wall of a room in a whorehouse, of little sheep lost in a storm. He wept late at night in Joey Adams’s nook on Forty-third Street just off Broadway when songwriters and singers like Harry Tiernery and Violinsky played ballads on the piano. “Mother” songs tore Ketchel’s heart out. He had a voice like a crow’s, but he used to dream of building a big house someday in Belmont, Michigan, near his hometown of Grand Rapids. In it there would be a music room where he would gather with hundreds of old friends and sing all night.

The record of his life is soaked with fable and sentiment. The bare facts are these:

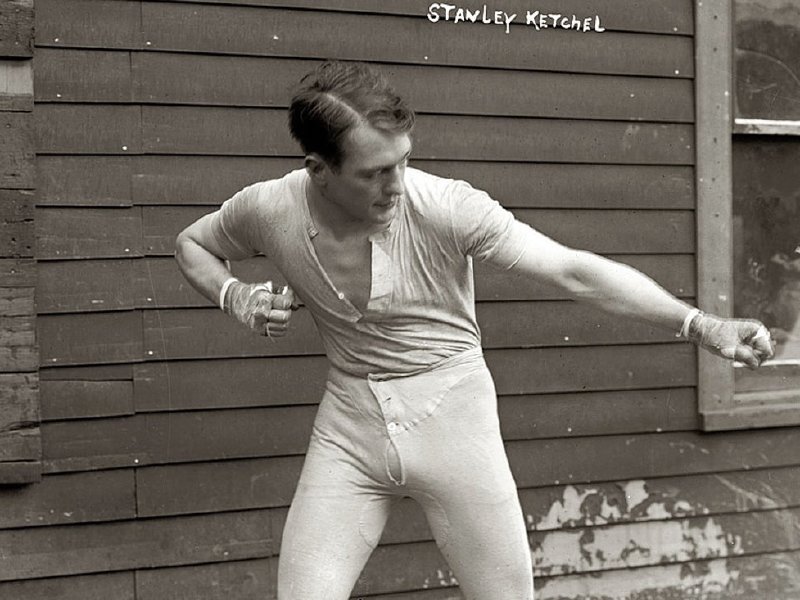

Ketchel was born Stanislaus Kiecal on September 14, 1886. His father was a native from Russia, of Polish stock. His mother, Polish-American, was fourteen when Ketchel was born. His friends called him Steve. He won the world’s middleweight championship in California at the age of twenty-one. He lost it to Billy Papke by a knockout and won it back by a knockout. He was a champion when he died by the gun. He stood five feet nine. He had a strong, clean-cut Polish face. His hair was blondish and his eyes were blue-gray.

When you come to the statement made by many who knew him that they were “devil’s eyes,” you border the land of fancy in which Ketchel and his admirers lived. But there was a true fiendishness in the way he fought. Like Jack Dempsey, he always gave the impression of wanting to kill his man. Philadelphia Jack O’Brien, a rhetoric-lover whom he twice knocked unconscious, called Ketchel “an example of tumultuous ferocity.” He could hit powerfully with each hand, and he had the stamina to fight at full speed through twenty- and thirty-round fights. He knocked down Jack Johnson, the finest heavyweight of his time, perhaps of any time, who outweighed him by thirty to forty pounds. He had a savagery of temperament to match his strength. From a combination of ham and hot temper, and to make things tougher on the world around him, he carried a Colt .44 — Hype Igoe always spoke of it dramatically as the “blue gun” — which was at his side when he slept and in his lap when he sat down to eat. At his training camp at the Woodlawn Inn near Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York, Ketchel once fired the gun through his bedroom door and shot his faithful trainer Pete (Pete the Goat) Stone in the leg when Pete came to wake him up for work. Ketchel then leaped into his big red Lozier car and drove Stone to the hospital for treatment.

“He sobbed all the way,” said Igoe, “driving with one hand and propping up Pete’s head with the other.”

The great moments of Ketchel’s life were divided among three cities: San Francisco, New York, and Butte, Montana. Each city was at its romantic best when Ketchel came upon it.

Ketchel was a kid off the road, looking for jobs or handouts, when he hit Butte in 1902 at the age of sixteen. He had run away from Grand Rapids by freight when he was fourteen. In Chicago, as Ketchel used to tell it, a kindly saloonkeeper named Socker Flanagan (whose name and function came straight from Horatio Alger) saw him lick the usual Algeresque bully twice his size and gave him a job. It was Flanagan, according to Ketchel, who taught him to wear boxing gloves and who gave him the name of Ketchel. After a time the tough Polish boy moved west. He worked as a field hand in North Dakota. He went over the Canadian line to Winnipeg, and from there he described a great westering arc, through mining camps, sawmills, and machine shops, riding the rods of the Canadian National and the Canadian Pacific through rugged north-country settlements like Revelstoke, Kamloops, and Arrowhead, in British Columbia, till he fetched up on the West Coast at Victoria. He had a .22 rifle, he used to recall, that he carried like a hunter as he walked the roads. In Victoria, he sold the .22 for boat fare down across the straits and Puget Sound to Seattle. In Seattle he jumped a Northern Pacific freight to Montana. A railway dick threw him off the train in Silver Bow, and he walked the remaining few miles of cinders to Butte.

Butte was a bona fide dime-novel town in 1902. It was made for Ketchel. Built on what they called “the richest hill in the world,” it mined half the country’s copper. The town looked sooty and trim by day, but it was red and beautiful by night, a patch of fire and light in the Continental Divide. As the biggest city on the northwest line between Minneapolis and Spokane, it had saloons, theaters, hotels, honky-tonks, and fight clubs by the score. Name actors and name boxers played the town. When Ketchel struck the state, artillery was as common as collar buttons.

Ketch caught on as a bellhop at the hotel and place of amusement named the Copper Queen. One day, he licked the bouncer — and became a bouncer. As Dan Morgan says, he enjoyed the work; so much so that he expanded it, fighting all comers for $20 a week for the operator of the Casino Theater, when he was not bulldogging drunks at the Copper Queen. If Butte was made for Ketchel, so was the fight game. He used to say that he had 250 fights around this time that do not show in the record book. In 1903, he was already a welterweight, well grown and well muscled.

All hands, including Ketchel, agree that his first fight record, with Jack (Kid) Tracy, May 2, 1903, was a “gimmick” fight, a sample of a larcenous tradition older than the Marquis of Queensberry. The gimmick was a sandbag. Tracy’s manager, Texas Joe Halliday, who offered ten dollars to anyone who could go ten rounds with his boy, would stand behind a thin curtain at the rear of the stages on which Tracy fought. When Tracy maneuvered the victim against the curtain, Texas Joe would sandbag him. Ketchel, tipped off, reversed the maneuver. He backed Tracy against the curtain, and he and the manager hit the kid at the same time. The book says, KO, I round.

The book also says that Ketchel lost a fight to Maurice Thompson in 1904. This calls for explanation, and, as always, the Ketchel legend has one ready. A true folk hero does not get beat, unless, as sometimes happened to Hercules, Samson, and Ketchel, he is jobbed. At the start of the Thompson fight a section of balcony seats broke down. Ketchel turned, laughing, to watch — and Thompson rabbit-punched him so hard from behind that Ketch never fully recovered. In the main, the young tiger from Michigan needed no excuses. He fought like a demon. He piled one knockout on top of another. He would ride the freights as far as northern California, to towns like Redding and Marysville, carrying his trunks and gloves in a bundle, and win fights there. In 1907, after he knocked out George Brown, a fighter with a good Coast reputation, in Sacramento, he decided to stay in California. It was the right move. In later years, when Ketchel had become mythological, hundreds of storytellers “remembered” his Butte adventures, but in 1907 no one had yet thought to mention them. In California the climate was golden, romantic, and right for fame. And overnight Ketchel became famous.

When minstrels sing of Ketch’s fight with Joe Thomas, they like to call Thomas a veteran, a seasoned, wise old hand, a man fighting a boy. The fact is, Thomas was two weeks older than Ketchel. But he had reputation and experience. When Ketchel fought him a twenty-round draw in Marysville — and then on Labor Day, 1907, knocked him out in thirty-two rounds in the San Francisco suburb of Colma — Ketchel burst into glory as suddenly as a rocket.

Now there was nothing left between him and the middleweight title but Jack Twin Sullivan. The Sullivans from Boston, Jack and Mike, were big on the Coast. Jack had as good a claim to the championship (vacated by Tommy Ryan the year before) as any middleweight in the world. But he told Ketchel, “You have to lick my brother Mike first.” Ketchel knocked out Mike Twin Sullivan, a welter, in one round, as he had fully expected to do. Before the fight he saw one of Mike’s handlers carrying a pail of oranges and asked what they were for. “Mike likes an orange between rounds,” said the handler.

“He should have saved the money,” said Ketchel.

Mike Twin needed no fruit; Jack Twin was tougher. Jack speared Ketchel with many a good left before Ketchel, after a long body campaign, went up to the head and knocked his man cold in the twentieth round. On that day, May 9, 1908, the Michigan freight-stiff became the recognized world champion.

His two historic fights with Billy Papke came in the same year. Papke, the Illinois Thunderbolt from Spring Valley, Illinois, was a rugged counterpuncher with pale, pompadoured hair and great hitting power. Earlier in 1908 Ketchel had won a decision from him in Milwaukee. The first of their two big ones took place in Vernon, on the fringe of Los Angeles, on September 7. Jim Jeffries, the retired undefeated heavyweight champion — Ketchel’s only rival as a national idol — was the referee. The legend-makers do not have to look far to find an excuse for what happened to Ketchel in this one. It happened at the start, and in plain sight. In those days it was customary for fighters to shake hands — not just touch gloves — when the first round began. Ketchel held out his hand. Papke hit him a left on the jaw and a stunning right between his eyes. Ketchel’s eyes were shut almost tight from then on; his brain was dazed throughout the twelve rounds it took Papke to beat him down and win the championship.

Friends of Ketchel used to say that to work himself into the murderous mood he wanted for every fight he would tell himself stories about his opponents: “The sonofabitch insulted my mother. I’ll kill the sonofabitch!” No self-whipping was needed for the return bout with Papke. The fight took place in San Francisco on November 26, eleven weeks after Papke’s treacherous coup d’état in Los Angeles. It lasted longer than it might have — eleven rounds; but this, they tell you, was pure sadism on Ketchel’s part. Time after time Ketchel battered the Thunderbolt to the edge of a coma; time after time he let him go, for the sake of doing it over again. It was wonderful to the crowd that Papke came out of it alive. At that, he survived Ketchel by twenty-six years, though he died just as abruptly. In 1936, Billy killed himself and his wife at Newport Beach, California.

“His genes were drunk” is the way one barroom biologist puts it.

It was around this time that Willus Britt brought his imagination to bear on Ketchel — that is, he moved in. Willus was a man who lived by piecework. An ex-Yukon pirate, he was San Francisco’s leading fight manager and sport, wearing the brightest clothes in town and smoking the biggest cigars. He once had a piece of San Francisco itself — a block of flats that was knocked out by the 1906 earthquake. When Willus sued the city for damages, the city said the quake was an act of God. Willus pointed out that churches had been destroyed. Was that an act of God? The city said it didn’t know, and would Willus please shut the door on the way out?

Britt won Ketchel over during some tour of San Francisco night life by his shining haberdashery and his easy access to champagne and showgirls. In this parlay, champagne ran second with Ketchel. He did drink, some, and the chances are that he smoked a little opium. But he didn’t need either — he was one of those people who are born with half a load on. “His genes were drunk” is the way one barroom biologist puts it. His chief weaknesses were women, bright clothes, sad music, guns, fast cars, and candy.

Once in 1909, after Britt had taken him in high style (Pullman, not freight) from the Coast to New York, Ketchel was seen driving on Fifth Avenue in an open carriage, wearing a red kimono and eating peanuts and candy, some of which he tossed to bystanders along the way. The kimono, gift of a lady friend, was a historical part of Ketchel’s equipment. A present-day manager remembers riding up to Woodlawn Inn, Ketch’s New York “training” quarters, with Britt one day, in Willus’s big car with locomotive sound effects. As they approached the Inn, the guest saw a figure in red negligee emerge from the cemetery nearby.

“What’s that?” he asked, startled.

“That’s Steve,” said Britt, chewing his cigar defiantly.

Britt had looked up Wilson Mizner as soon as he and Ketchel reached New York. Mizner, a fellow Californian and Yukon gold-rusher, was supposed to know “the New York angle”; Britt signed him on as an unsalaried assistant manager. Free of charge, Mizner taught Ketchel the theory of evolution one evening (or so the legend developed by Mizner runs). Much later the same night Mizner and Britt found Ketchel at home, studying a bowl of goldfish and cursing softly.

“What’s the matter?” said Mizner.

“I’ve been watching these ___________ fish for nine hours,” snarled Ketchel, “and they haven’t changed a bit.”

Mizner, a part-time playwright at this time and a full-time deadbeat and Broadway night watchman, was a focus of New York life in 1909-10, the gay, brash, sentimental life of sad ballads and corny melodrama, of late hours and high spending, in which Ketchel passed the last years of his life. Living at the old Bartholdi Hotel at Broadway and Twenty-third Street, playing the cabarets, brothels, and gambling joints, Ketchel was gayer and wilder than ever before. He still fought. He had to, for he, Britt, and Mizner (unsalaried or not) were a costly team to support. Physically the champion was going downhill in a handcar, but he had the old savagery in the ring. His 1909 fight with Philadelphia Jack O’Brien ended in a riddle. O’Brien, a master, stabbed Ketchel foolish for seven rounds. In the eighth, O’Brien began to tire. In the ninth, Ketchel knocked him down for nine. In the tenth and last round, with seven seconds to go, Ketchel knocked O’Brien unconscious. Jack’s head landed in a square flat box of sawdust just outside the ropes near his own corner, which he and his handlers used for a spittoon.

“Get up, old man!” yelled Major A.J. Drexel Biddle, Jack’s society rooter from Philadelphia. “Get up, and the fight is yours!”

But Jack, in the sawdust, was dead to the world. The bout ended before he could be counted out. By New York boxing law at the time, it was a non-decision fight. O’Brien had clearly won it on points; just as clearly, Ketchel had knocked him out. Connoisseurs are still arguing the issue today. Win or lose, it was a big one for Ketchel, for O’Brien was a man with a great record, who had fought and beaten heavyweights. The next goal was obvious. Jack Johnson, the colored genius, held the heavyweight championship which Jim Jeffries had resigned. To hear the managers, promoters, and race patriots of the time tell it, the white race was in jeopardy — Johnson had to be beaten. Ketchel had no more than a normal share of the race patriotism of that era; but he was hungry, as always, for blood and cash, and he thought he could beat the big fellow. Britt signed him for the heavyweight title match late in the summer of 1909, the place to be Sunny Jim Coffroth’s arena in Colma, California, the date, October 16.

“At the pace he’s living, I can whip him,” Ketch told a newspaperman one day. He himself had crawled in, pale and shaky, at 5 a.m. the previous morning. Johnson — on whom, at thirty-one, years of devotion to booze and women had had no noticeable effect whatever — called around to visit Ketchel in New York one afternoon in his own big car. He was wearing his twenty-pound driving coat, and he offered to split a bottle of grape with the challenger.

“I wish I’d asked him to bet that coat on the fight,” said Ketchel afterward. “I could use it to scare the crows on my farm.”

Ketchel was still dreaming of the farm, the big house in Belmont, Michigan, where he would live with his family and friends when he retired. He had a little less than one year of dreams left to him. One of them almost came true — or so the legend-makers tell you — in the bright sunshine of Colma on October 16. Actually, legends about the Ketchel-Johnson fight must compete with facts, for the motion pictures of the fight — very good ones they are, too — are still accessible to anyone who wants to see them. But tales of all kinds continue to flourish. It’s said that there was a two-way agreement to go easy for ten rounds, to make the films more saleable. It’s also said, by Johnson (in print) and his friends, that the whole bout was meant to be in the nature of exhibition, with no damage done, and that Ketchel tried a double cross. It’s also said, by the Ketchel faction, that it was a shooting match all the way and that Steve almost beat the big man fairly and squarely. Ketchel fans say Ketchel weighed 160; neutrals say 170; the official announcement said 180¼. Officially, Johnson weighed 205½; Ketchel’s fans say 210 or 220.

Two of his teeth impaled his lip, and a couple more, knocked off at the gum, were caught in Johnson’s glove.

There’s no way of checking the tonnage today. About the fight, the films show this: Johnson, almost never using his right hand, carried his man for eleven rounds. “Carried” is almost literally the right word, for Johnson several times propped up the smaller fighter to keep him from falling. Once or twice he wrestled or threw him across the ring. Jack did not go “easy”; he did ruthless, if restrained, work with his left. One side of Ketchel’s face looked dark as hamburger after a few rounds. But in the twelfth round all parties threw the book away, and what followed was pure melodrama.

Ketchel walked out for the twelfth looking frail and desperate, his long hair horse-tailed by sweat, his long, dark trunks clinging to his legs. Pitiful or not to look at, he had murder in his mind. He feinted with his left, and drove a short right to Johnson’s head. No one had ever hit Li’l Artha squarely with a right before, though the best artists had tried. Ketchel had the power of a heavyweight; and Johnson went down. Then, pivoting on his left arm on the canvas, he rolled himself across the ring and onto his knees. In the film you can almost see thoughts racing through his brain — and they are not going any faster than referee Jack Welch’s count. Perhaps it was the speed of this toll that made up his mind. Johnson, a cocky fellow, always figured he had the whole world, not just one boxer, to beat, and he was always prepared to take care of himself. He scrambled to his feet at what Welch said was eight seconds. Ketchel, savage and dedicated, came at him. The big guy drove his right to Steve’s mouth, and it was over.

No fighter has ever looked more wholly out than Ketchel did, flat on his back in the middle of the ring — though once, just before the count reached ten, he gave a lunge, like a troubled dreamer, that brought his shoulders off the floor. This spasmodic effort to rise while unconscious is enough to make the Ketchel legend real, without trimmings. It was an hour before Ketchel recovered his senses. Two of his teeth impaled his lip, and a couple more, knocked off at the gum, were caught in Johnson’s glove.

Ketchel recuperated from the Johnson fight at Hot Springs, Arkansas. Sightseers saw him leading the grand ball there one night, dressed like the aurora borealis, with a queen of the spa on his arm. A few months later he was back in New York, touching matches to what was left of the candle. He kept on fighting, for his blonde-champagne-and-candy fund. They tell you that Mizner (Britt had died soon after the Johnson bout) once or twice paid money to see that Steve got home free in a fight — like the one with the mighty Sam Langford in April 1910, which came out “No decision-6.” Dan Morgan says a “safety-first” deal was cooked up for Ketchel’s second-to-last fight, a New York bout with a tough old hand name Willie Lewis. Dan’s partner, and Willie’s manager, was Dan McKetrick. On the night before the fight the two Daniels went to mass; and Morgan heard McKetrick breathe a prayer for victory (which startled him) and saw him drop a quarter in the contribution box. In the fight, Willie threw a dangerous punch at Ketchel, and Ketchel, alerted to treachery, stiffened Willie.

“You’re the first man,” said Morgan to McKetrick afterward, “that ever tried to buy a title with a two-bit piece.”

“Tut, tut,” said McKetrick. “Let us go see Ketchel, and maybe adopt him. If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.”

McKetrick’s hijacker’s eye had been caught the night before by the sight of Mizner, nonchalant and dapper, sitting in a ringside seat drawing up plans for a new apartment for himself and Ketchel, instead of working his fighter’s corner. Maybe Ketch could be pried loose from that kind of management. Morgan and McKetrick called on Ketchel at the Bartholdi Hotel. They offered to take him off Mizner’s hands. Ketchel, who respected Mizner’s culture but not his ring wisdom, was receptive. The two flesh-shoppers went to see Mizner, to break the news to him.

“Why, boys, you can have the thug with pleasure,” said Mizner. “But did he remember to tell you that I owe him three thousand dollars? How can I pay him unless I manage him?”

They saw his point. Mizner would need money from Ketchel to settle with Ketchel. Ketchel saw it, too, when they reported back to him. He turned white and paced the floor like a panther at the thought of being caged in this left-handed way. But he stayed under Mizner management.

Hype Igoe was Ketchel’s closest crony in the final months that followed. To Hype, the supreme mythmaker, whatever Steve did was bigger than life. He used to tell and write of Ketchel’s hand being swollen after a fight “to FIVE TIMES normal size!” He wrote of a visit Ketchel made, incognito, to a boxing booth at a carnival one time, when he called himself Kid Glutz and “knocked out SIX HEAVYWEIGHTS IN A ROW!” He told a story about a palooka who sobbed in Ketchel’s arms in the clinches in a fight one night. “What’s the matter, kid?” asked Ketchel. Between sobs and short jolts to the body, his opponent explained that he was being paid $10 a round, and feared he would not last long enough to make the $60 he needed to buy a pawnshop violin for his musical child. Ketchel carried him six rounds, and they went to the pawnshop together, in tears, with the money. The next time Hype wrote it, the fiddle cost $200. Ketchel made up the difference out of his pocket, and he and the musician’s father bailed out the Stradivarius, got drunk on champagne, and went home singing together.

There was a grimmer, wilder side of Ketchel’s mind that affected the faithful little sportswriter deeply. Ketchel used to tell Hype — he told many people — that he was sure he would die young. The prediction made a special impression on Igoe on nights when the two went driving together in the Lozier, with Ketchel at the wheel. As the car whipped around curves on two tires and Igoe yelped with fear, Ketchel would say, “It’s got to happen, Hype. I’ll die before I’m thirty. And I’ll die in a fast car.” Luckily for Hype and other friends, it happened in a different way when it happened, and Ketchel took nobody with him. The world was shocked by the Michigan Tiger’s death, but on second thought found it natural that he should pass into the great purple valley by violence. To Igoe’s mind it was the “blue gun” that Steve romantically took with him everywhere that was responsible.

Ketchel had knocked out a heavyweight, Jim Smith, in what proved to be the last fight of his life, in June 1910. Though he could fight, he was in bad shape, like a fine engine abused and over-driven. To get back his health he went to live on a ranch in Conway, Missouri, in the Ozarks, not far from Springfield. His host, Colonel R.P. Dickerson, was an old friend who had taken a fatherly interest in Ketchel for two or three years. Ketchel ate some of his meals at the ranch’s cookhouse — he took an unfatherly interest in Goldie, the cook. Goldie was not much to look at. She was plain and dumpy. But because she was the only woman on the premises, Ketchel ignored this, as well as the fact that Walter Dipley, a new hand on the ranch, was thought to be her husband.

On the morning of October 16, as Ketchel sat at the breakfast table, Dipley shot him in the back with a .38 revolver. Ketchel was hit in the lung. He lived for only a few hours afterward.

Igoe used to say that it was because Ketchel had his own .44 in his lap, as always at meals, that he was shot from behind, and that he was shot at all. There was evidence later, after Dipley had been found by a posse with Ketchel’s wallet in his possession, that husband and wife had played a badger game with money as a motive. Goldie, it turned out, was a wife in name only. Dipley, whose right name was Hurtz, had a police record. They were both sent to jail; Dipley, sentenced to life, did not get out on parole till twenty-four years later.

Ketchel’s grave is in the Polish Cemetery in Grand Rapids.Visitors will find a monument over it, built by Colonel Dickerson — a slab of marble twelve and a half feet high, topped by a cross and showing these words:

STANLEY KETCHEL

BORN SEPT. 14, 1886

DIED OCT. 16, 1910

A Good Son and Faithful Friend.

Legend had built an even more durable monument to Ketchel. Of the one in stone, a neighbor with a few drinks in him once said, “Steve could have put his hand through that slab with one punch.”

[Photo Credit: George Grantham Bain]