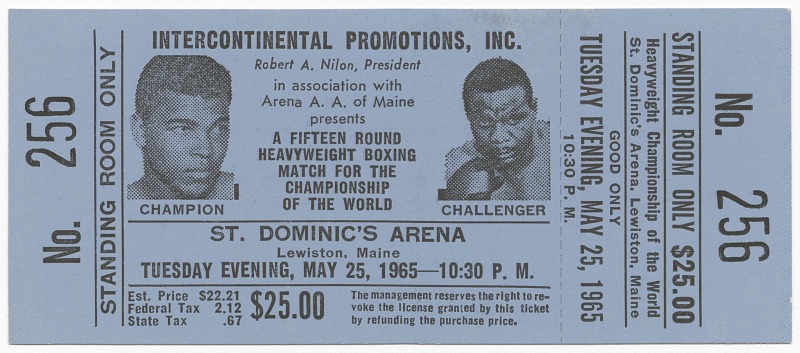

Although until last week I had never personally attended a prize fight, I knew what I expected to see. The boxers’ glistening, circling bodies and the hoarse roar of the crowd had become familiar to me through years of exposure to Hollywood fight movies. Not only the crummy ambiance of the sport in general, but its most vivid details—the precise patterns of the sweat trickling down the fighters’ foreheads, the blurry flash of the mouthpiece, even the exact slapping sound of leather on flesh—had all been revealed to me many times in much-magnified, pore-by-pore movie close-ups. Still, when I went to Lewiston, Maine, to watch Sonny Liston and Cassius Clay battle for the heavyweight championship of the world, I was worried. It wasn’t the prospect of bloodshed that scared me, but the fear that despite years of slavish attention to Hollywood boxing movies, I might not really understand what was going on. I was afraid that when I was really seated at last at ringside, the lights glaring, my heart pounding, I might through ignorance fail to experience the primal sense of human combat which makes the rest of the sleazy game worthwhile.

When I watch a real fight on TV, I have great difficulty following or even seeing the rapid-fire right-to-the-body, left-to-the-jaw activities which seem so apparent to the announcer and the roaring fans. By the time I can figure out whose right and left is which, everything has turned around. I desperately did not want this to happen when I was sitting at ringside. And since my very first fight was to be not only for the heavyweight title, but also Act II of a classic ring drama unequaled since Nibelungen. I felt especially obliged both to comprehend and to savor the spectacle. I had no inkling then that my first fight would be boxing’s last.

From the moment I landed in Maine two days before the fight until the evening of the battle itself, I constantly felt I was in some movie, though I couldn’t be sure which one. The turreted, broken-down old Poland Spring House Hotel, with its endless, tilted corridors and fretwork verandas fogged with cigar smoke, looked like a Charles Addams version of Marienbad. The crowds of beefy, sportshirted fight fans, on the other hand, looked straight out of Warner Brothers’ casting department. But among them I readily recognized some old newsreel faces. The stiff-limbed old man in the rocker was surely Jim Braddock, and there was Joe Walcott, genially cuddling a small boy in a cretonne chair. Of course, I always knew who I was: the Dumb Broad at her first fight, asking silly questions.

I asked a sharply dressed veteran sportswriter what I should watch for on the night of the fight. “It’s all a big carnival, honey,” he rasped. “Just take your position on the Ferris wheel and wave your balloon.”

After the press build-up of sinister bodyguards and Muslim assassins, I expected to find an Oriental spy movie atmosphere at Muhammad Ali’s camp. But at his motel headquarters rock ’n” roll music blared from an open doorway, several of his sparring partners friskily frugged along balconies, and hordes of girls waited worshipfully in the grassy courtyard and surged forward shrieking each time the champion popped out of his room to caper and wave.

Sonji Roi, Clay’s 24-year-old-bride, looked like a very pretty Oriental kitten right out of an Arabian Nights B-movies. While Cassius clowned, she was busy dyeing a wiglet as part of her preparations for the next night’s elaborate toilette. She had never seen a real prize fight either, she said, but she wasn’t the least worried about her husband getting hurt. “He won’t get his nose mashed,” she told me. “He’s too conscious of how he looks.” Just then Clay himself pranced into the bathroom, glanced in the mirror, and said, “She’s almost as pretty as me.” Sonji beamed. As I left the royal suite, I saw a super cliché, a Stepin Fetchit type, sprawled in an old chair and guarding the door, just like in a Will Rogers movie. And it was Stepin Fetchit.

When I actually got into the arena on fight night, I felt momentarily reassured. The lights were blazing, the cigar smoke was suffocating, a hoarse voice was announcing the preliminary fights, and the sweat gleaned on the young fighters’ backs. As all of us waited for the main event, everything looked and smelled just the way it was supposed to.

My seat was a good one. I sat near Cassius’ corner, right next to Cus D’Amato, Floyd Patterson’s ex-manager and, I knew from my reading, one of the wisest old men of boxing. I asked him what I should watch and he said, “Watch everything, the most interesting thing will arrest your attention.”

I didn’t see the punch, I didn’t understand why Liston didn’t get up, I didn’t know what Referee Walcott was doing, and I didn’t understand why or how Clay had won.

I took a good deal of comfort from sitting next to D’Amato, and swiftly came to regard him as the grizzled Casey Stengel of the fight game. “Do you feel the gentle excitement beginning to build?” he inquired politely when the preliminary bouts ended. I didn’t yet, but perhaps that was because I’d just seen two clumsy men knocked flat in the first two rounds of their fights. Although their performance, I knew, bore small resemblance to Clay’s slogan—“Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee”—D’Amato by then had made me feel that I would know a butterfly when I saw one. “Boxing,” he said, “is the only sport in the world where you don’t have to know anything. Just watch.”

What I watched next was Singer Robert Goulet stumble past me to the ring muttering, “I can’t remember the words.” As a matter of fact, he didn’t remember the words—“by the dawn’s early night” his voice boomed out over the crowd—but I remember Goulet much better than I do Liston or Clay, perhaps because he spent a longer time in the ring.

As for the world’s heavyweight championship match itself, all my worst fears were confirmed. I didn’t see the punch, I didn’t understand why Liston didn’t get up, I didn’t know what Referee Walcott was doing, and I didn’t understand why or how Clay had won. “What happened?” I asked D’Amato.

“Shoot right,” he said unsatisfactorily and melted away into the disgruntled crowd. As I too drifted through the crowd at ringside, seeking answers, a final fight began. Suddenly there was a mighty thud right behind me, and the evening’s fourth warrior had crashed to the mat, this one in 35 seconds of the first round.

I felt awfully depressed, but there was a certain solace in slowly coming to realize that millions of people around the world who knew a great deal about boxing felt exactly the way I did.

It wasn’t the fight game or even a movie that I’d been watching but the sleaziest sort of carnival side show. The whole event reminded me of one of those roadside freak shows one sees advertised along empty stretches of highway. The first sign says, “Monster alive—5 miles.” The second promises, “Man-eating beast—one mile.” But when you finally get there and pay your dollar to look at the monster alive, all you see is a dead snake.