Thaddeus Stevens? Who knew? One of the least-understood of Dylan mysteries has to do with influences: His music seems to come from everywhere, and from nowhere but him. You can listen to endless droning folk balladeers, and you can listen to Buddy Holly, Robert Johnson, Hank Williams. You can read Milton and Keats, as Christopher Ricks does–but as I argued recently in these pages, Dylan’s works are best considered as songs, not poems.

So where does it come from, the whole Dylan carnival: the comic surreal characters, the recurring cryptic femme fatales, the ecstatic ironies, the declamatory cadences and the insinuating sneers? The unmistakable Dylan voice. Yes, he invented himself, but not out of nothing.

That’s where Chronicles, Volume One, Dylan’s memoir, is most illuminating. For one thing, it feeds an admittedly parochial pride: He makes it clear that what made Dylan, Dylan was New York, New York. Specifically, the New York of the Village–more explicitly the Village when it was still The Village, and not a theme park for bohemia. The Village and all that talk, all those hopped-up riffs, epic espresso-fueled denunciations and appreciations. He found a way to distill the attitude, transcend the bullshit and turn New York talk into song.

Dylan writes that he came to New York from Hibbing, Minn., searching for something, for a “template,” he calls it–a template for the raw gift buried inside him like the iron ore buried beneath the Mesabi Range that brooded magnetically over Hibbing. The story he tells is of the time before he became an instant seer, 1961, the time before his first record came out, when he was, for all anyone knew, just another struggling Village character on the folk scene.

At its best, in the New York chapters, Chronicles is a kind of prose ballad to the Village, to Village characters, to bohemian goddesses, to the peculiarly skewed Village state of mind. The cold-water-flat Village of the early 60’s when it was still home to a stew of autodidact geniuses, mad seers and obsessed oddballs–the crazy attic of America. The sailors and ex-cons turned hopped-up philosophers, who stacked their shelves with Byron, Thucydides and obscure tomes on Thaddeus Stevens and lived with pre-Raphaelite bohemian goddesses like the one Dylan calls Chloe.

Could I pause for a moment, before I get to Thaddeus Stevens, to pay respect to Chloe? She seems to be the first in a long line of wised-up, sad-eyed ladies, the bohemian goddesses, Beat Angels, visionary Johannas, who splendidly, irrevocably, ruin lives in Dylan’s best heartbreak songs. The obvious choice is “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” but I’d go for “Queen Jane Approximately” from Highway 61 Revisited or “If You See Her, Say Hello” from Blood on the Tracks. (By the way: If you do see her, say hello.)

“Chloe had red gold hair, hazel eyes, an illegible smile,” Dylan tells us, and “illegible smile” tells you all you need to know. He met her at some Village crash pad where she was living with a guy named Ray. “She worked as a hat-check girl at the Egyptian Gardens, a belly-dancing dinner place on 8th Avenue; also posed as a model for Cavalier magazine. ‘I’ve always worked,’ she said.”

At another point Dylan tells us: “She was cool as pie, hip from head to toe, a Maltese kitten, a solid viper–always hit the nail on the head.” Case closed.

Except to say that this archetypal Village angel seems to have been an influence on his verbal style as well as his emotions. Chloe is given to uttering cryptic, gnomic, bohemian-goddess-type aphorisms: “She also had her own ideas about the nature of things,” Dylan writes, “told me that death was an impersonator, that birth is an invasion of privacy.”

In other words, in her idiosyncratically “illegible” way of talking about “the nature of things,” she uttered a certain kind of cryptic, Dylanesque rhetoric before Dylan did.

“Death is an impersonator / Birth is an invasion of privacy” could be a couplet from Street Legal or Blood itself. Sort of a parody of less-than-great Dylan, but some of Dylan is a parody of less-than-great Dylan.

So Chloe was a dangerous Blonde on Blonde when Dylan was still a folkie singing sea chanteys and the like. “What could you say?” Dylan asks of her riffs on “the nature of things.” “It’s not like you could prove her wrong.”

That last rueful, bemused remark is the tone of Dylan’s voice in the book: sometimes capable of rhapsodic ecstasies (usually when talking about other music and other musicians), but more often the sharp, sardonic observer you hear in his songs at their best.

He’s the best kind of music critic: He really reacts. He’s a kind of Geiger counter dialed up to 11; music is radioactive to him.

Consider the way he describes “Billy the Butcher,” the kind of Village character who gave the place what Dylan calls its “carnie vitality.” A would-be singer who hung out around the Cafe Wha? folk scene, Billy “looked like he came out of nightmare alley. He only played one song–‘High-Heel Sneakers’– and he was addicted to it like a drug …. Billy would always preface his song by saying, ‘This is for all you chicks.’ The Butcher wore an overcoat that was too small for him, buttoned tight across the chest. He was jittery and sometime in the past he’d been in a straitjacket in Bellevue, also had burned a mattress in a jail cell … all kinds of bad things had happened to Billy. There was a fire between him and everybody else. He sang that one song pretty good, though.”

You have to love that last line, the perfect deadpan Dylan twist, comic but affectionate too. One can’t help think it comes from a wry recognition of the Billy the Butcher inside himself, the part of himself capable of being knocked silly by a song, the part that can love a song to death.

In fact, some of the best moments in the book are ones in which Dylan describes the way certain songs, certain singers, became his “High-Heel Sneakers,” the way that upon hearing certain singers he is recurrently knocked out, paralyzed, mesmerized, devastated. There are the obvious ones–Hank Williams, Woody Guthrie, Robert Johnson–but some obscure and unexpected ones too: Lonnie Johnson(?), Johnny Rivers(!), Harold Arlen (my friend Jonathan Schwartz will be in heaven). He’s the best kind of music critic: He really reacts. He’s a kind of Geiger counter dialed up to 11; music is radioactive to him. I think some people are born with a gene for song obsession, even those who can’t play a note like myself. I’ll admit it: I was once obsessed with “High-Heel Sneakers” too.

By the way, I don’t use the Geiger-counter metaphor idly: Another weird detail we learn from Chronicles about Dylan’s Village days is that, at one point, he actually owned a Geiger counter. It seemed there were a lot of them in Village pads. It’s a detail that reminds us of the shadow of nuclear terror that hung over America and impressed itself even more forcefully on the seismic souls of the Village, whose seize-the-day (or seize-the-cappuccino) mentality owes much, it seems in retrospect, to an apprehension of an onrushing nuclear Holocaust so soon after the horror of Hitler’s came to light. Norman Mailer, a Village contemporary of Dylan’s, talks about it most memorably in “The White Negro,” in which he contends (among many other things) that the madness of Mutual Assured Destruction (M.A.D.) as a nuclear doctrine made secret psychopaths of us all.

I’ve argued in the past that Dylan’s best work has an affinity with the “black humor” genre of 60’s American literature: Heller’s Catch-22, Kesey’s Cuckoo’s Nest.Underlying both is that awareness of M.A.D.-ness. (Can you believe we only had a dozen years between the end of nuclear terror and the onset of the post-9/11 kind? I wish someone had told me.)

So there he is, Dylan, little older than a high-school graduate, toting his Geiger counter and his guitar around from one Village crash pad to another, when he comes on one crash pad in particular, the one inhabited by Chloe, it turns out, whose nominal live-in boyfriend, Ray, has the crammed bookshelves with which Dylan distracted himself from Chloe.

In fact, I think it is to his crush on Chloe that we owe his discovery of Thaddeus Stevens.

Dylan makes the “library” in Ray and Chloe’s place sound like the Old Curiosity Shop of literature: “books on typography, epigraphy, philosophy …. Books like Fox’s Book of Martyrs, The Twelve Caesars, Tacitus lectures and letters to Brutus … Thucydides’ The Athenian General–a narrative which would give you chills … it talks about how human nature is always the enemy of anything superior …. Sometimes I’d open a book and see a handwritten note scribbled in the front, like in Machiavell’s The Prince, there was written, ‘The spirit of the hustler.’”

(Later, in a line that is one of my favorite ones in the book, Dylan takes issue with Machiavelli on the question of Love: “Machiavelli said … that it’s better to be feared than loved–but sometimes in life,” Dylan says, “someone who is loved can inspire more fear than Machiavelli ever dreamed of.”)

Along with this profusion of the classical and the contemporary–The Temptation of St. Anthony and Ovid’s Metamorphoses next to the autobiography of Davy Crockett, Milton’s “On the Late Massacre in Piedmont” (his “protest poem,” Dylan calls it: point for Christopher Ricks)–Dylan finds some old tome about Thaddeus Stevens, and his Geiger counter reacts to the presence of the fiery-tempered anti-slavery crusader.

“He’s from Gettysburg and he’s got a club foot like Byron,” Dylan tells us. (He later drops the fact he’s read the entire 16,000-line Byron epic Don Juan “and concentrated fully from start to finish,” and you can hear it in his sense of humor, his romantic posturings and his feminine endings.) Anyway, Dylan tells us, Stevens “grew up poor, made a fortune and from then on championed the weak and any other group who wasn’t able to fight equally. Stevens had a grim sense of humor, a sharp tongue and a white-hot hatred for the bloated aristocrats of his day … once referred to a colleague on the floor of the [Capitol] chamber as ‘slinking in his own slime’ … denounced his foes as those whose mouths reeked from human blood … called his enemies a ‘feeble band of lowly reptiles who shun the light and who lurk in their own dens.’”

Needless to say, one hears the prophetic anger of the early Dylan jeremiads like “Masters of War” and “The Times They Are A-Changin” in this appreciation of Stevens’ wrathful eloquence. Later Dylan tells us–evidently following up on his Thaddeus Stevens reading–that he spent an intense period in the 42nd Street library reading old newspapers and pamphlets from the Civil War era.

And then he says a fairly remarkable thing about the power of his Civil War reading: “Back there America was put on the cross, died and was resurrected. There was nothing synthetic about it. The godawful truth of that would be the all-encompassing template behind everything that I would write.”

The template at last! Thanks to Thaddeus Stevens (and Chloe and Village autodidact Ray).

The template behind everything? Well, when you think about it, love is a kind of Civil War in Dylan songs, sometimes between two people, sometimes within one; sometimes a Civil War where the slaves don’t always want to be free.

I don’t want to give the impression the book is all about New York, although it begins and then circles back and ends in the Village of the early 60’s. It’s a strangely structured patchwork first volume of a memoir, one that jumps forward from the time before Dylan cut his first record to the late 60’s when he was already a sensation, a mythic prophet driven to Salinger-like reclusiveness by those who thought he’d got the Answer. In this episode, he’s called upon by Archibald MacLeish to write songs for a play about Evil.

The section is somewhat unsatisfying–as the collaboration turns out to be (although I hope the songs haven’t been lost). It’s most memorable for his asides: Dylan claims to have recorded an entire album based on Chekhov short stories, but doesn’t say which one (I’d guess Blood on the Tracks or the one that closes with “Dark Eyes”). He tells us that his first “performances” were in a Passion Play(!)–the Black Hills Passion Play of South Dakota, in which he played a Roman soldier with a nonspeaking part yet felt, for the first time, “like a star.” He doesn’t tell us whether the Passion Play would have an influence on his now-lapsed conversion to Christianity; in fact, in this volume he doesn’t say anything about that era at all.

The thing I’m looking forward to most in future volumes (the next one, I hope) is an account of what I still think was his greatest creative period as a writer and performer — from Bringing It All Back Home to Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde and the live tours of that period with Robbie Robertson and the Hawks. Instead, we have to be satisfied with an interesting but a bit overwrought description of the making of the so-so Oh Mercy (1989) with Daniel Lanois. (O.K., there is one addictive song on Oh Mercy: “Most of the Time,” a killer.)

But if we don’t learn anything about his conversion to Christianity, we learn something brand-new about a different kind of mystical conversion experience, a musical conversion experience that seems spiritual as well as metaphysical and musical. If New York gave him his content and the “template” for what he wrote, this is a story about how he re-invented his delivery of that content, how he re-invented the way he sang and played. He wasn’t just a writer, after all, although writers tend to see him through the lens most familiar to them; he was a performer.

His description of his performance conversion experience makes it sound both freaky and momentous (to Dylan, at least). I still don’t know what to make of it.

It’s 1987, and Dylan’s fallen into a black hole, a crisis both musical and spiritual. He couldn’t stand singing his old songs; they’d become dead to him: “It was like carrying a package of heavy rotting meat” trying to bring them to life onstage. Then something happened: He was in San Rafael, where he’d begun rehearsals for a tour with the Grateful Dead. They were asking him to do some songs he’d rarely sung, and he hated it, and he walked out saying he’d left something at his hotel–but really, he says, on the verge of walking out on the whole tour, on live performance altogether.

He wanders out into the San Rafael gloom, goes into a bar and hears a singer whose name he doesn’t even remember (or at least specify) doing Billy Eckstine–type standards, and suddenly he hears something and everything changes. He hears the jazz singer doing something with his voice, has an earthshaking revelation: “Something internal came unhinged.” He says he “could feel how [the singer] worked at getting his power …. I knew where the power was coming from and it wasn’t his voice … now I knew I could perform any of these songs without them having to be restricted to the world of words. This was revelatory.”

Say what? It gets stranger and stranger from there on. He has a series of revelations, including a “new system” for singing and strumming that he’d been taught by a jazz guy named Lonnie Johnson. “Lonnie took me aside one night [in the 60’s] and showed me a style of playing based on an odd- instead of even-number system,” on the number 3 rather than 2. After that San Rafael night, Dylan makes what he describes as the momentous shift from 2 to 3. “I don’t know why the number 3 is more metaphysically powerful than the number 2, but it is,” he says. And that using the number-3-based system, “You can manufacture faith out of nothing and there are an infinite number of patterns and lines that connect from key to key …. As long as you recognize it, you can turn the dynamic around architecturally in a second.”

Um, whatever you say, Bob. And he has plenty more to say: “With a new incantation code to infuse my vocals with manifest presence I could ride high, unconsciously drag endless skeletons from the closet. Thematic triplets making everything hypnotic …. My lyrics, some written as long as twenty years earlier, would now explode musicologically like an ice cloud. Nobody else played this way and I thought of it as a new form of music.” He rejoins the Dead at rehearsal and everything is magically renewed for him.

Is it possible that he’s putting us on? You read this and you flip the pages back to where he says, offhandedly, after the revelation that night with the Dead, “Maybe they just dropped something in my drink.” If so, I’ll have what he’s having.

Whatever it was, it gets him on the road again: On the verge of dropping out, he now books two hundred concerts for the next year–and only illness (an infection around the heart, wouldn’t you know) has suspended this “endless tour” ever since. I suspect we ought to be grateful to the Dead, whatever they did or didn’t do to his drink. The entire section is wild: You rarely hear an artist of this magnitude talking so rhapsodically–and technically–about his own work. I look forward to musicians and musically minded critics like Tim Riley explicating this further.

It’s almost exhausting to read Dylan tell us of his serial mystical revelation, and I’m glad the book circles back in time to New York again at the end. To the Village of the 60’s, where he falls in love and gets a record contract and hears old Robert Johnson recordings and the Brecht/Weill ballad “Pirate Jenny,” and tells us that “if I hadn’t gone to [the Village’s] Theatre de Lys and heard ‘Pirate Jenny,’ it might not have dawned on me to write songs like ‘It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),’ ‘Mr. Tambourine Man,’ ‘Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,’ ‘Who Killed Davey Moore?’, ‘Only a Pawn in Their Game,’ ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’ and some others like that,” he says.

What you come away liking about the guy is that he’s Warren Zevon’s “Excitable Boy” without the actual serial-killer downside, the way his Geiger counter is always going off, and he’s generous in an eloquent way about those who set it off. And though he’s known for his snarky takes on New York types–“Positively 4th Street,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” etc.–he seems to have gotten over the old, petty Village grudges (and believe me, as a former Village Voice writer I know they can last), and to have undergone a conversion in his attitude toward the city that fame made him flee from.

Back when Dylan converted to Christianity, I was asked to write about it. I had recently interviewed him (for Playboy) and he talked about the sound he’d always been searching for: It was “that thin, that wild mercury sound” he told me, and it was a New York sound: “It was the sound of the streets, that ethereal twilight light–on a particular type of building. A particular type of people–arguments in apartments and the clinking of silverware and knives and forks–usually it’s the crack of dawn.”

“The jingle-jangle morning?” I ventured, quoting the phrase from “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

“Right,” he said.

I’d interviewed him at a time when his life was falling apart, shortly before his conversion to Christianity, so seeing the divorce hell he was going through, I kind of understood the stairway to Heaven that the conversion offered him temporarily. But I was still saddened about it. I ended the piece (“Born-Again Bob: Four Theories,” it’s reprinted in The Dylan Companion) by talking about the peculiarly New Age flavor of the denomination that Dylan had embraced. I talked–very disrespectfully, I know–about the logo of the California congregation he’d joined: The picture of Jesus in the logo made “Him look like … a late-Seventies smoothie, a quintessentially Californian Christ.”

I closed by addressing Dylan rhetorically: “I don’t necessarily want you to leave Christ and come back to your roots. But I do think you ought to leave California and come back to New York.”

Dylan still lives in California (for those few nights he’s not on the road). But in this book, he comes back to New York. He brings it all back home again.

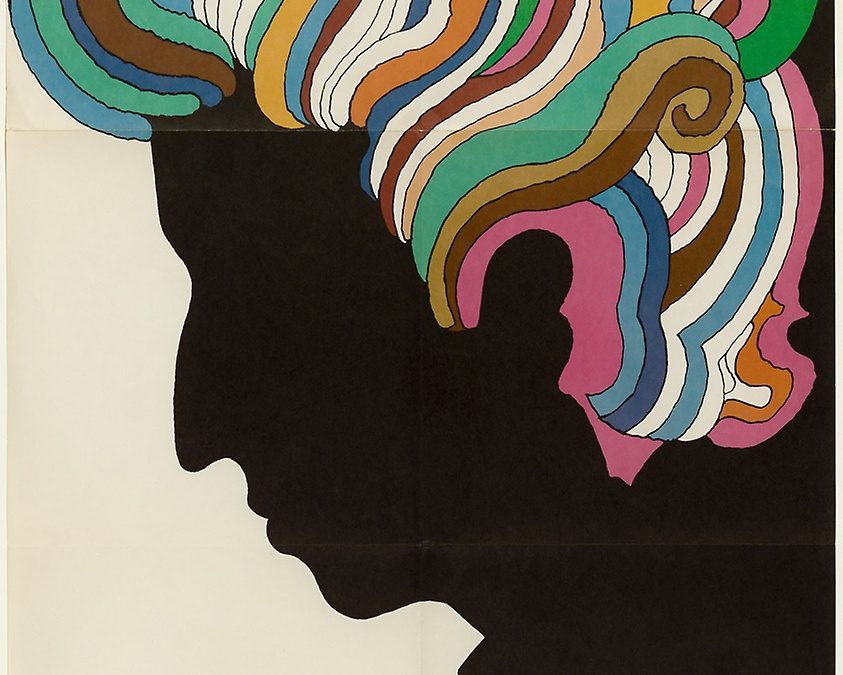

[Featured Image: Milton Glaser]