Revolutionary fever caught on at an elegant private dinner party at Trumps in West Hollywood one Saturday night late last year. A study in hip, Melrose Avenue minimalism, Trumps is very groovy. The banquettes are covered with woven raffia. The tables are molded from concrete. And the art, which changes every month or so, runs the gamut from stark, Isamu Noguchi sculptures bearing names like Atomic Haystack to Jasper Johns lithographs. The restaurant is Joan Keller Selznick’s favorite place in town, and that’s why she invited Warren Beatty, Gary Hart, Orion Pictures President Michael Medavoy, Los Angeles Times writers Charles Champlin and Robert Scheer, L.A. Weekly publisher Jay Levin, Jerry Brown’s guru Nathan Gardels, and nearly a dozen others there to celebrate Rosario Murillo’s arrival in Los Angeles.

A soldier in the 1979 insurrection against Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza, Murillo is a poet whose hallucinatory verse (“the summer’s heat … the battle on the rooftops … a kiss when we had stopped believing in kisses … life which for us is unquestionably life-blood, the Revolution”) romanticizes what is now known in Managua as “the triumph.” A mother of seven and the wife of Sandinista junta Commandant Daniel Ortega, she also happens to be beautiful – dark, tropical, irresistible.

At a wealthy businessman’s residence in Beverly Hills where she was staying, Murillo mesmerized actor Ed Asner and former Black Panther Huey Newton.

And here Murillo was at Trumps, sitting at a table adorned by baskets of garden-grown red roses, intoxicating everyone with tales of the revolution and pleas for help. The Ronald Reagan administration, she said, was trying to destroy the Sandinista government.

The food this evening was sublime – a banquet consisting of hearts of romaine salad, Norwegian salmon atop a duxelles mushroom puree, crème brule, and bottle after bottle of Beaujolais Nouveau. But Murillo was really the main course. All weekend, in fact, people had been devouring her.

At a wealthy businessman’s residence in Beverly Hills where she was staying, Murillo mesmerized actor Ed Asner and former Black Panther Huey Newton. At a very private meeting with Tom Hayden and Jane Fonda, she sought the aid of America’s premiere liberal couple. At a genteel old mansion in Hancock Park, she held a group of several hundred spellbound for an hour as she described the power of the revolution.

Yet there’s no doubt that this splendid gathering hosted by Joan Selznick (director of the 1970 Oscar-winning short subject film The Magic Machines and wife of producer and MGM scion Daniel Selznick) was really the highlight of Murillo’s mission to Hollywood. Throughout dinner, Murillo, who was educated in Europe, persisted in speaking Spanish, which her interpreter would then translate. But when it came time for coffee, Warren Beatty coaxed her to use English. “Don’t be insecure about it,” he said.

How could she resist?

Conversation quickly picked up. At the time, rumors ran rampant that the U.S. Army was poised to invade Nicaragua and that American-trained contras were in fact already engaging Sandinista troops in combat. But everyone here knew all about that. Murillo was concerned with elucidating the finer points – the junta’s rationale for censoring the Nicaraguan press, the reasons behind Pope John Paul II’s coolness to the Sandinistas, and the prospects for national elections. On each topic she was eloquent and forceful.

The night was Murillo’s. Hart, circumspect because he was seeking the presidency, sat quietly taking it all in. The others, almost to a one, asked supportive, almost reverential questions. In the face of this attractive woman’s bullet-tested certitude, it was hard not to feel like an ugly American, and if there were certain exquisite ironies to be pondered, it was easier not to broach them. Oh, one of the Times reporters had the temerity to raise the specter of Commander Zero (Zero – the nom de guerre of Eden Pastora – was the hero of the Sandinista revolution; after the fighting was over, he broke with the junta). But Murillo vanquished this apostate by denouncing Zero as “a dangerous egotist.”

It went on like this until nearly midnight. Finally, Murillo, her dark eyes shining, her radiant black hair spilling over her shoulders, made her farewells.

A half hour or so after Murillo departed, Jerry Brown – who’d been detained at another party – arrived to find a few lingering members of the Selznick group.

“How was it?” he asked.

“She knocked our socks off,” replied one of them.

In the months following Murillo’s appearance at Trumps, people in Hollywood began mobilizing to make the mighty push that they seemed to believe would have to come from the film capital of the world to keep the United States out of an imperialistic war in Central America. As preparations progressed, the image of the Sandinista poetess dwelt in the communal subconscious like some revolutionary archetype. She was the new Che Guevara, only better. Like Guevara, she was young, well educated, upper class – and also sexy. She had marched with the proletariat but was so hip that Jay Levin wrote in the L.A. Weekly that she embodied “the prevailing liberal values of this country … especially L.A.” Levin’s endorsement of Murillo was actually mild compared to what some others were saying and writing, but typically his praise was un-tempered by a single nagging doubt. Yet that’s how revolutionary fever manifested itself. Unlike other fevers, it didn’t make things blurry at all. Just the opposite. It cleared every murky matter right up. The Sandinistas and guerrillas in El Salvador were obviously right, and U.S. government policies were obviously wrong. Ambiguities flat disappeared and were replaced by comforting resolve. As Richard Hofstadter, the late Columbia University historian, once observed: “To be confronted by a simple and unqualified evil is no doubt a kind of luxury.” It all worked that way.

In essence, an infatuation with the forces of radical change in Central America offered members of the Hollywood Left the privilege of avoiding the intricate and paradoxical nature of the conflict in the region. As even Peter Davis, the liberal director of Hearts and Minds, the Academy Award-winning anti-Vietnam War documentary, recently wrote in the Nation, trying to come to terms with the situation in Central America is like trying to decipher a pointillistic painting from up close: each dot contradicts every other, and perspective is almost impossible to find. While the Somoza dictatorship and the Salvadoran plutocracy were guilty of horrendous acts, the Sandinistas had persecuted Nicaragua’s Miskito Indian population, and the Salvadoran revolutionaries had violently disrupted their country’s elections. Central Americans, of course, were entitled to self-determination, but the United States couldn’t afford to ignore Cuban or Soviet intervention in the region. And if the Reagan administration’s positions seemed bellicose, so did many of the activities of the revolutionaries in Nicaragua and El Salvador. Sadly, there just weren’t many easy answers. Which is precisely why it wasn’t hard to find Rosario Murillo alluring.

Hollywood’ fascination with Central America didn’t just happen overnight. One winter evening early in 1982 at Trader Vic’s at the Beverly Hilton – a Hawaiian luau of a restaurant known for its huge Polynesian drinks and its Republican car-dealer clientele – Ed Asner, producer Bert Schneider, longtime activist Bill Zimmerman, and several others got together to talk over “the Central American thing.”

The group had just screened the documentary El Salvador: Another Vietnam, at the Beverly Hills Recreation Center. The movie featured a sequence showing the corpses of four American nuns found murdered in El Salvador that was so disturbing some people couldn’t watch.

But the people sitting around the table at Trader Vic’s had no intention of averting their eyes. Schneider, aside from his work as a producer (Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces, Hearts and Minds and, most recently, Broken English, a film about Third World revolutionaries and lesbian and interracial romance) had substantially financed Huey Newton’s Panther Defense Fund during the 1970s and had read a controversial telegram from Hanoi at the 1975 Oscar ceremonies when he accepted the award for Hearts and Minds. Zimmerman, the sharp and successful producer not only of commercials for U.S. Senate candidates but of Jane Fonda’s immensely successful Work Out tapes, had helped found Medical Aid for Indochina in the early 1970s and had been a member of SDS. Asner, president of the Screen Actors Guild and at the time star of the very popular Lou Grant show, was well known for his outspoken commitment to various causes.

After arriving back in Los Angeles, Bert Schneider told an acquaintance over dinner, “There’s nothing more beautiful than a new revolution.”

Each of these men was championing a different agenda. Asner wanted to do whatever it took to “get the word out about what’s happening.” Zimmerman, on the other hand, was trying to raise money for a new group he’d been instrumental in founding: Medical Aid for El Salvador.

Schneider, a tall, handsome Hollywood Galahad, was adept at bringing people together. It didn’t take him long to see that Asner’s and Zimmerman’s desires dovetailed. Since Zimmerman had already raised $25,000, why not fly to Washington, alert the press, and present a check to be used for medical care in El Salvador on the State Department steps?

In February that’s exactly what Asner, Zimmerman, Schneider, Howard Hesseman of WKRP in Cincinnati, and Ralph Waite of The Waltons did. Of course, it turned into a scene that made the national news, and Asner, who did most of the talking, took a lot of heat. (Three months later, CBS cancelled Lou Grant and Asner, invoking memories of McCarthyism, continues to maintain that had he never protested U.S. activity in Central America, he’d still be on the air.) The fallout notwithstanding, the presentation of the check in Washington was the first move. Some eminent members of the Hollywood Left had taken sides.

In September of 1982, four months after Lou Grant was discontinued and a full year before the evening at Trumps, Blasé Bonpane – a cleric and academic who in 1967 had been expelled from Guatemala, where working as a Maryknoll priest he’d been active in community organizing – flew from Los Angeles to Mexico City to attend a conference called “Dialogue of the Americas.” Bonpane, a steady, warm, balding intellectual, was a somewhat contradictory character. A priest by faith and a professor by profession (he taught Latin American history at UCLA until 1970, when he says he was fired by then Governor Reagan because of the ideas he endorsed in the classroom and later published in his thesis Liberation Theology and the Central American Revolution), he was at heart a Hollywood kid. He’d grown up in the Hollywood Hills during the heyday of the studios on a street where his neighbors included William Bendix and Alan Ladd. His father had been a showbiz lawyer with an office at Hollywood and Vine. Down deep, Bonpane adored actors.

Not long after arriving in Mexico City, Bonpane – at the invitation of Ernesto Cardenal, an old friend, a supporter of the Sandinistas, and the priest Pope John Paul refused to let kiss his ring on the pontiff’s last visit to Managua – went to the Nicaraguan Embassy for a meeting with Rosario Murillo. Murillo, aside from her other duties and passions, is secretary general of the Sandinista Cultural Workers Association, and she had a favor to ask of Bonpane. With all his connections in the movie world, could he organize a group of Hollywood celebrities for a trip to Central America? “If people come, they’ll see we’re no threat to anyone,” Murillo said.

Bonpane gave her his pledge.

When Bonpane returned to California, he sequestered himself at home in Mar Vista and started working the telephone. By November, he’d put together the first delegation from filmdom to the Central American front. Among the volunteers to land in the initial wave later that month were Bert Schneider, Joan Selznick, Alvin Sargent (the screenwriter of Ordinary People), David Clennon (one of the stars of Missing), Haskell Wexler (the Oscar-winning cinematographer), and Bonpane himself.

After establishing a beachhead at the Protocol House, a group of comfortable homes built by the Somoza dictatorship for its military nabobs, the Hollywood forces moved out to the front – the mountainous region of northern Nicaragua on the Honduran border. Fighting there between Sandinista guardsmen and contras was hot.

The first day in, the Hollywood troops saw action – sort of. Late in the afternoon, they were attempting to ford the Rio Negro River, where a bridge had been blown out, when their two Japanese minibuses broke down. As dusk fell, a nervous thrill ran through the group. The contras almost always struck at sunset, and here they all were with just a couple of Sandinista escorts. When it grew so dark that no one could see, a Sandinista military transport truck finally came along and ferried them safely back to Managua. But no one could forget the experience. They’d been on maneuvers in enemy territory, and the enemy was armed with American weapons.

In their travels around Nicaragua, the visitors from Hollywood were all struck by the poverty and destruction. Peasants working for American multinational corporations were living in chicken coops. Horror stories of torture and mayhem were commonplace. It was heart wrenching, so grim, in fact, that almost everyone would come to believe that deprivation and degradation alone brought about revolution in Central America. Communism was more a symptom than a cause. Perhaps so, but since Bonpane’s group was being hosted by the Sandinistas, it would have probably been hard to see it any other way.

The Sandinistas, in fact, were just wonderful to everyone, setting up meetings with government officials, giving tours of facilities such as prisons, schools, and the film institute, and even scheduling a conference with Orlando Tardencillas, the Nicaraguan who had disappointed Alexander Haig when the then-secretary of state trotted him out in Washington and he refused to confess that Nicaragua was “exporting revolution” to El Salvador. Nearly everyone in the Hollywood group was armed with a camera or tape recorder, and the Sandinistas were absolutely open to being photographed. Haskell Wexler was actually carrying his professional equipment, which he used to film the documentary Target Nicaragua.

Only one real incident occurred during the adventure, and that was when the group paid a call on U.S. Ambassador Anthony Quainton. Things got off to a bad start when American Embassy officials asked everyone to refrain from using their cameras and recorders. But the bombshell didn’t drop until it came time for each member of the Hollywood contingent to make a “personal statement” to the ambassador. That’s when Bert Schneider, according to a friend, loudly and harshly told Quainton, “A man of good conscience would stand up and speak the truth and break with the Reagan administration. If you don’t do it, someday the truth will come out and then there’ll be a Nuremberg trial, and people wearing blue shirts and black pants will suffer the same fate that the war criminals suffered.” Quainton, who would later resign his post, was wearing a blue shirt and black pants.

By all other measures, it was a pleasant trip, and that was due to Rosario Murillo. She went out of her way to ensure everyone’s happiness.

After arriving back in Los Angeles, Bert Schneider told an acquaintance over dinner, “There’s nothing more beautiful than a new revolution.”

By the spring of 1983, Blasé Bonpane had created an organization called the Office of the Americas and established headquarters at St. Augustine-by-the-Sea in Santa Monica. Soon he was running a veritable Central American travel agency for actors like Diane Ladd and Mike Farrell and for well-known liberals from the Northeast like Bella Abzug, attorney Michael Kennedy, and Jesse Jackson’s wife, Jacqueline. The ports of call: Nicaragua, Honduras, and El Salvador.

At the same time, Central Americans began arriving in Hollywood. During her visit to Nicaragua, Joan Selznick became interested in the works of Nicaraguan filmmakers. The upshot: At Filmex 1983, Selznick threw a luncheon at Trumps for the Nicaraguan contingent attending the festival. It was an afternoon that foreshadowed an event to come. A host of celebrities, including Brenda Vaccaro and Tatum O’Neal, made appearances, but the star of the show was a very famous Nicaraguan indeed: Bianca Jagger.

As the celebrants dined on Chinese chicken salad and mushroom soup at tables topped by arrangements fashioned from the flags of Nicaragua, the United States, and the Sandinista party, Selznick and Jagger made remarks in praise of Central American filmmakers. However. the real triumph of the week came later, when a Nicaraguan movie titled Al Cino and the Condor won Filmex’s award for best feature film of the year. Hollywood had captured Nicaragua, and now Nicaragua had captured Hollywood.

So dawned the era of revolutionary fever. Nicaragua and El Salvador had suddenly become critical issues. Ronald Reagan was declaring the United States mobile, agile, and hostile. And everyone in Hollywood was familiar with at least one side of the story because it seemed like everyone knew someone who’d been down there with Blasé Bonpane. It was at this propitious moment that Rosario Murillo enjoyed her night at Trumps.

A week or so after Murillo left town, important members of the Hollywood Left received mailgrams urging them to attend “an emergency meeting” to help avert war in Central America. The text read, “There are alarming indications that the United States is considering bombing, shelling, and/or ground invasion of El Salvador and/or Nicaragua … According to the D.C.-based Council on Hemispheric Affairs, Guatemalan and Honduran troops have moved to the borders facing Nicaragua and El Salvador. Behind them are U.S. American [sic] soldiers.” The communiques were signed by Blake Edwards (producer, director, and writer of “10”), Michael Douglas (producer of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and partial owner of the L.A. Weekly), Mike Farrell (one of the stars of M*A*S*H), and several others. Like Paul Revere’s midnight ride, the mailings were intended to alert the community. On December 11, about a hundred people showed up at Douglas’s home at the top of Benedict Canyon to prepare battle plans.

Ed Asner came. So did Bill Zimmerman. So did Bonpane. And so did all sorts of actors and activists, among them Margot Kidder, Ed and Mildred Lewis (producers of Missing), Stanley Sheinbaum (chair emeritus of the ACLU Foundation of Southern California and husband of a Warner), and Jay Levin.

In a sense this powwow was intended to be educational. A number of speakers took the floor to hammer home the message: revolutions are inevitable in Central America, and the United States is on the wrong side. The lineup included a couple representatives from Washington-based “commissions” and one lucid, eloquent man – Dr. Charles Clements. Author of the forthcoming Witness to War, An American Doctor in El Salvador, he had some chilling things to say about the horrors he’d seen in Central America.

After the classroom session concluded, the organizers of the meeting got down to business. Everyone wanted to know what Hollywood could do to present an alternative view of events in Central America to the American public. While this was Douglas’s house and while Mike Farrell was chairing the event, it was really Jay Levin’s program. Formerly a New York Post reporter (he covered Abbie Hoffman and other underground personalities for the paper), Levin had become the Thomas Paine of revolution in Nicaragua and El Salvador. In the words of one ex-L.A. Weekly writer, “he invented Central America in this town.” The Weekly, which had already published a position paper by Blasé Bonpane, would the very next week feature Rosario Murillo on its cover. Levin’s goal was to figure out how to make enough money in Hollywood to fund a national television advertising campaign in opposition to the White House stance on Central America.

But not everyone at Douglas’s home shared Levin’s high hopes. For one thing, no one was certain such a plan was feasible – economically or otherwise. Eventually, Stanley Sheinbaum would come up with another idea. It was less ambitious, but it would fly. Sheinbaum suggested that they do what Hollywood does best – put on a show. Everyone agreed, and the activists (now banded together under the name Committee of Concern), hired a couple full-time organizers and started making plans.

In January, Connecticut Senator Chris Dodd (a vocal opponent of Reagan’s position on Nicaragua and El Salvador) flew to Los Angeles and gave a talk to members of the Committee of Concern in the executive dining room of Twentieth Century Fox Studios. He praised the film community for its “courage.” The next month he appeared at Norman Lear’s house in Brentwood for a hush-hush fundraiser, where he and Charles Clements helped collect money to be split among various Washington-based liberal watchdog organizations – including the Commission on U.S.-Central American Relations and the Central America Peace Campaign – that were focusing attention on the region.

In the meantime, Bonpane was in regular contact with Murillo in Managua, and in late February he put tother the kind of Central American itinerary that would jack up the temperature of anyone under the spell of revolution fever.

Joining Bonpane this time were Bert Schneider and his wife Greta, writer Carol Caldwell, and Andrew Kopkind, an editor at the Nation. Meeting them in Managua was a bona fide star: Julie Christie.

At first, the trip was like any other. The group made a run to the Honduran border, where they saw what became yet another female Sandinista icon: a lonely soldier on patrol with her automatic rifle and 250 rounds of ammunition – 249 to use on the contras and the last to use on herself. They explored Managua. Audiences were granted with officials. But these were just the appetizers.

Late one afternoon when the group was traveling near Honduras (on this occasion riding in reliable Mercedes buses), it received a radio message to return to Managua. The junta had invited everyone to dinner at its private dining room – an ornate chamber that during the Somoza regime had been a watering hole for millionaires.

Murillo was there. So was Ernesto Cardenal. So was Daniel Ortega. Over fried bananas, rice and beans, and bottles of Victoria and Tona beer, the Hollywood contingent and the junta discussed the fate of the Sandinista regime and the American policies threatening it. Afterward, one of the Americans said, “It made me feel so bad to be from the United States that I wanted to make a public confession of guilt.”

But the late-night communion was not the highlight of the trip. No, this week happened to mark a special occasion in Nicaragua – the anniversary of the death of Augusto Sandino, a legendary guerilla fighter killed by Somoza in 1934 and from whom the Sandinistas take their name.

One beautiful morning, with some 100,000 peasants gathered in the main square of Managua, the Schneiders, Bonpane, Kopkind, Christie, and the others took their places on the platform with Nicaragua’s rulers. Gazing out across the vast space, they could see the National Palace, a huge cathedral hung with a giant banner depicting Sandino, dozens of human pyramids formed by workers in the coffee and cotton brigades, and hundreds of signs that read: SANDINO VIVE!

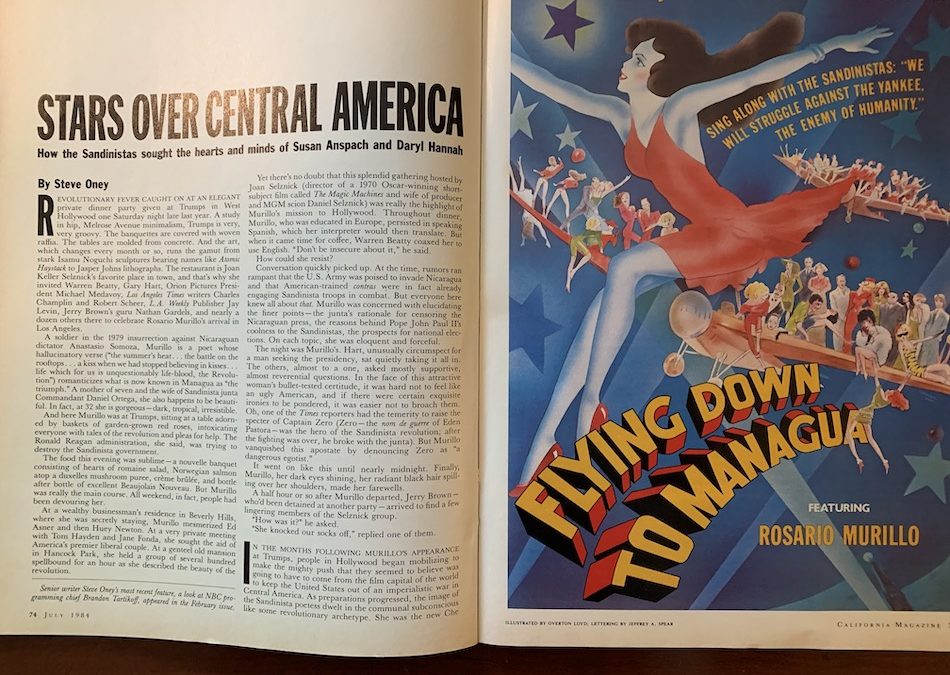

The ceremony was short and powerful. Carlo Mejia Godoy played the accordion and guitar. Daniel Ortega announce that elections would take place on November 4. Then the multitude sang the Sandinista hymn, with its memorable line: “We will struggle against the Yankee, the enemy of humanity.”

Several hours later Bonpane asked Julie Christie if she’d consider starring in the script he’d written about a priest and Central America. She said she would.

Less than a month later, everyone was back in Hollywood. The Committee of Concern was ready to unveil its presentation, the first of what organizers hoped would become a series of latter-day Chautauqua shows designed to present a picture of events in Nicaragua and El Salvador different from the U.S. government version. Stanley Sheinbaum was the host, and he kicked off the program at Los Angeles’s Fairfax High School with just the right pedagogic touch by quoting from Carlos Fuentes’s 1983 Harvard commencement address, a document now well-known to the Hollywood Left. In his talk, Fuentes coined a metaphor for Central America. The region, the novelist said, was governed by an internal clock that revealed the time to be a quarter till noon, a moment rife with revolutionary portent. The United States, he went on to say, had reached this hour long ago. To illustrate Fuentes’s notion, Sheinbaum wheeled a huge clock whose hands were turned to 11:45 onto the school auditorium stage, and he urged the 1,400 people gathered in the hall (1,500 more stood outside on the sidewalks listening via loudspeakers) to study the timepiece during the program.

Then the festivities began. Jackson Browne and Bonnie Raitt sang antiwar songs. Roy Scheider, Diane Ladd, Susan Anspach, and Martin Sheen gave readings and testimony describing atrocities ordained by the oligarchs (“the colonel dumped dozens of ears on the table like dried peach halves” and “the peasants were bombed and butchered with machetes, and stakes were jammed between the women’s legs”). Though doubtless sincere, the actors spoke in voices resonating with elongated Latinate vowels and overstressed final syllables (San Salvador was now “San Saalvadoer,” Chile was “Cheeelay”). At last, Jacobo Timmerman, the Solzhenitsyn of the Left, was escorted out like a battleship to pound in the heavy ideas about the inevitability of revolution.

But Sheinbaum’s showstopper wasn’t even on the program. “I now want to introduce someone,” he said solemnly, “and it was not he who gave us the crook Spiro or the accursed Kissinger. There’s a flaw in our system when this man can’t be president, but he can be present.”

To this preamble out marched George McGovern, now politically six feet under but reincarnated tonight as the Left’s El Cid. Clad in his traditional uniform – dark suit and dark, shiny shoes – and radiating Presbyterian rectitude, McGovern beamed down on the audience and said, “If we could all go there, we’d side with the insurgents in El Salvador … where our present policy flies in the face of all history and is a repudiation to our own revolution.”

A longing for the years when villains were war-loving capitalists and heroes were exiled in Canada may only have been one impulse here tonight. Something else, something quite new, something exciting was at work.

The crowd roared. But the night was still young, and the 100 or so who could afford the $100 a head that was being asked at Michael Douglas’s front door brought their enthusiasm with them to Benedict Canyon.

Douglas lives in one of those deceptive Beverly Hills ranch affairs that from the street appear to be standard suburban issue but open up into spacious villas overlooking all of Los Angeles. From the back porch the vistas are breathtaking. On this clear, moonlit evening, however, no one was paying much attention to the view, for just about everyone who was anyone in the cause was gathered around the pool.

Sitting beneath a Solarflo heater (popular in orange groves and essential at stylish, outdoor affairs), Jacobo Timmerman was holding Jerry Brown, Joan and Dan Selznick, and two attractive young women in thrall with an account of the relationship between U.S. activities in Nicaragua and Israeli arms shipments to Honduras. Just to the right of this seminar, Ed Asner was promising Jackson Brown, Daryl Hannah, and Hannah’s diminutive mother that he was ready to take decisive action against his political nemesis on Central American matters, Charlton Heston. “If I catch him,” Asner said, “I’m gonna kick his ass. He’s assassinating my character, and I don’t have much character left.”

Over by the bar, deep in conversation with Carol Caldwell (the writer who had journeyed to Managua several weeks before with Bonpane and was being introduced tonight as “the hostess to the revolution”) stood Huey Newton. Though the new cause was likely on his mind, Newton was saying, “I’ve got a tremendous development deal with Columbia to write my life story.”

Floating everywhere on the patio were lesser and greater lights. There was Mike Farrell. The was Diane Ladd. There were Sean Daniel, president of Universal Pictures production, and Roy Scheider. Not far away, Jay Levin was talking with Stanley Sheinbaum, in Douglas’s absence (the actor was off promoting his new movie, Romancing the Stone) the unofficial host.

As the evening wore on, Sheinbaum and most of the others wandered in from the porch (which was ending up as an informal reservation for a group of American Indians who’d arrived with Browne) and headed to the dining room, where McGovern was installed.

The dining room was small and dominated by a table holding a massive arrangement of showy queen protea and a dozen silver trays bearing pasta salads from Orlando & Orsini. McGovern stood with his back to an obscure Whistler (among Douglas’s nineteenth-century masterpieces is even a work by John Kensett – one of those minor but influential members of the Hudson River school whose paintings separate the amateurs from the connoisseurs), eating tortellini with his fingers and, after wiping his hands, greeting disciples. Here came a droll gent wielding a baton fashioned from a rolled-up copy of the Nation. Then Robert Scheer, the Los Angeles Times reporter, walked up and remarked that he was pleased that McGovern had said something nice about his newspaper during his talk at the Concern program. Then two young women blushingly confessed that McGovern was the first candidate they’d been old enough to vote for in a presidential election. Gradually, almost everyone in the house filed by to pay homage, and to nearly all of them McGovern spoke of the “necessity for your involvement in keeping America out of another Vietnam.”

During this outpouring of affection for McGovern, Sheinbaum, Levin, Schneider, Asner, and several others strolled by and smiled. This was smart, producing the very symbol of Vietnam-era activism at a party intended to celebrate a new movement nostalgic for the simpler days of the early 1970s.

But a longing for the years when villains were war-loving capitalists and heroes were exiled in Canada may only have been one impulse here tonight. Something else, something quite new, something exciting was at work. The Hollywood Left had found its image, and in doing so had escaped the burden of substance. As the party continued into the evening, men and women would come and go, speaking of Rosario Murillo.