In some ways it seems so long ago: John F. Kennedy was a handsome young Senator, starting to campaign for the Presidency of the United States.

In some ways, it seems like yesterday: Richard M. Nixon was starting to campaign for the presidency of the United States.

It was August, 1960, when I first met Cassius Marcellus Clay, when he was 18 years old and brash and wide-eyed and naive and shrewd, and now more than a decade has elapsed, and John F. Kennedy is dead, and Richard M. Nixon is President, and those two facts, as well as anything, sum up how much everything has changed, how much everything remains the same.

It is ridiculous, of course, to link Presidents and prize fighters, yet somehow, in this case, it seems strangely logical. When I think back to the late summer of 1960, my most persistent memories are of the two men who wanted to be President and of the boy who wanted to be heavyweight champion of the world.

And he was a boy—a bubbling boy without a serious thought in his head, without a problem that he didn’t feel his fists or his wit would eventually solve.

He is so different now. He is so much the same.

We met a few days before he flew from New York to Rome to compete in the 1960 Olympic Games. I was sports editor of Newsweek then, and I was hanging around a Manhattan hotel where the American Olympic team had assembled, picking up anecdotes and background material I could use for my long-distance coverage of the Games. I spent a little time with Bob Boozer, who was on the basketball team, and with Bo Roberson, a broad jumper who later played football for the Oakland Raiders, and with Ira Davis, a hop-step-and-jump specialist who’d played on the same high school basketball team with Wilt Chamberlain and Johnny Sample. And then I heard about Cassius Clay.

He was a light-heavyweight fresh out of high school in Louisville, Kentucky, and he had lost only one amateur bout in two years, a decision to a southpaw named Amos Johnson. He was supposed to be one of the two best pro prospects on the boxing team, he and Wilbert McClure, a light-middleweight, a college student from Toledo, Ohio. I offered to show the two of them, and a couple of other American boxers, around New York, to take them up to Harlem and introduce them to Sugar Ray Robinson. Cassius leaped at the invitation, the chance to meet his idol—the man whose skills and flamboyance he dreamed of matching. Sugar Ray meant big money and fancy cars and flashy women, and if anyone had told Cassius Clay then he would someday deliberately choose a course of action that scorned those values, the boy would have laughed and laughed and laughed.

I wasn’t just being hospitable, offering to show the boxers around. I figured I could maybe get lucky and pick up a story. I did. And more.

He was, even then, an original, so outrageously bold he was funny. We all laughed at him, and he didn’t mind the laughter, but rode with it, using it to feed his ego, to nourish his self-image.

On the ride uptown, Cassius monopolized the conversation. I forget his exact words, but I remember the message: I’m great, I’m beautiful, I’m going to Rome and I’m gonna whip all those cats and then I’m coming back and turning pro and becoming the champion of the world. I’d never heard an athlete like him; he had no doubts, no fears, no second thoughts, not an ounce of false humility. “Don’t mind him,” said McClure, amiably. “That’s just the way he is.”

He was, even then, an original, so outrageously bold he was funny. We all laughed at him, and he didn’t mind the laughter, but rode with it, using it to feed his ego, to nourish his self-image.

But there was one moment when he wasn’t laughing, he wasn’t bubbling. When we reached Sugar Ray’s bar on Seventh Avenue near 124th Street, Robinson hadn’t shown up yet, and Cassius wandered outside to inspect the sidewalks. At the corner of 125th Street, a black man, perched on a soap box, was preaching to a small crowd. He was advocating something that sounds remarkably mild today—his message, as I recall, was simply buy black, black goods from black merchants—but Cassius seemed stunned. He couldn’t believe that a black man would stand up in public and argue against white America. He shook his head in wonderment. “How can he talk like that?” Cassius said. “Ain’t he gonna get in trouble?”

A few minutes later, as a purple Lincoln Continental pulled up in front of the bar, Cassius literally jumped out of his seat. “Here he comes,” he shouted. “Here comes the great man Robinson.”

I introduced the two of them, and Sugar Ray, in his bored, superior way, autographed a picture of himself, presented it to Cassius, wished the kid luck in the Olympics, smiled and drifted away, handsome and lithe and sparkling.

Cassius clutched the precious picture. “That Sugar Ray, he’s something,” he said. “Someday I’m gonna own two Cadillacs—and a Ford for just getting around in.”

I didn’t get to Rome for the Olympics, but the reports from the Newsweek bureau filtered back to me: Cassius Clay was the unofficial mayor of the Olympic Village, the most friendly and familiar figure among thousands of athletes. He strolled from one national area to the next, spreading greetings and snapping pictures with his box camera. He took hundreds of photographs—of Russians, Chinese, Italians, Ethiopians, of everyone who came within camera range. Reporters from Europe and Asia and Africa tried to provoke him into discussions of racial problems in the United States, but this was eight years before John Carlos and Tommie Smith. Cassius just smiled and danced and flicked a few jabs at the air and said, as if he were George Foreman waving a tiny flag, “Oh, we got problems, man, but we’re working ’em out. It’s still the bestest country in the world.”

He was an innocent, an unsophisticated goodwill ambassador, filled with kind words for everyone. Shortly before he won the Olympic light-heavyweight title, he met a visitor to Rome, Floyd Patterson, the only man to win, lose and regain the heavyweight championship of the world, and Cassius commemorated Patterson’s visit with one of his earliest poems:

You can talk about Sweden,

You can talk about Rome,

But Rockville Centre’s

Floyd Patterson’s home.

A lot of people said That Floyd couldn’t fight,

But they should’ve seen him

On that comeback night.

There was no way Cassius could have conceived that, five years later, in his most savage performance, he would taunt and torture and brutalize Floyd Patterson.

The day Cassius returned from Rome, I met him at New York’s Idlewild Airport—it’s now called JFK; can you imagine what the odds were against both the fighter and the airport changing their names within five years?—and we set off on a victory tour of the town, a tour that ranged from midtown to Greenwich Village to Harlem.

Cassius was an imposing sight, and not only for his developing light-heavyweight’s build, 180 pounds spread like silk over a six-foot-two frame. He was wearing his blue American Olympic blazer, with USA embroidered upon it, and dangling around his neck was his gold Olympic medal, with PUGILATO engraved in it. For 48 hours, ever since some Olympic dignitary had draped the medal on him, Cassius had kept it on, awake and asleep. “First time in my life I ever slept on my back,” he said. “Had to, or that medal would have cut my chest.”

We started off in Times-Square, and almost immediately a passerby did a double-take and said, “Say, aren’t you Cassius Clay?”

Cassius’s eyes opened wide. “Yeah man,” he said. “That’s me. How’d you know who I is?”

“I saw you on TV,” the man said. “Saw you beat that Pole in the final. Everybody knows who you are.”

“Really?” said Cassius, fingering his gold medal. “You really know who I is? That’s wonderful.”

Dozens of strangers spotted him on Broadway and recognized him, and Cassius filled with delight, spontaneous and natural, thriving on the recognition. “I guess everybody do know who I is,” he conceded.

At a penny arcade, Cassius had a bogus newspaper headline printed: CASSIUS SIGNS FOR PATTERSON FIGHT. “Back home,” he said, “they’ll think it’s real. They won’t know the difference.”

He took three copies of the paper, jammed them into his pocket, and we moved on, to Jack Dempsey’s restaurant. “The champ around?” he asked a waiter.

“No, Mr. Dempsey’s out of town,” the waiter said.

Cassius turned and stared at a glass case, filled with cheesecakes. “What are them?” he asked the waiter.

“Cheesecakes.”

“Do you have to eat the whole thing,” Cassius said, “or can you just get a little piece?”

Cassius got a little piece of cheesecake, a glass of milk and a roast beef sandwich. When the check arrived and I reached for it, he asked to see it. He looked and handed it back; the three items came to something like two and a half dollars. “Man,” he said. “That’s too much money. We coulda gone next door”—there was a Nedick’s hot dog stand down the block—“and had a lot more to eat for a whole lot less money.”

From Dempsey’s, we went to Birdland, a jazz spot that died in the 1960s, and as we stood at the bar—with Cassius holding a Coke “and put a drop of whisky in it”—someone recognized him. “You’re Cassius Clay, aren’t you?” the man said.

“You know who I is, too?” said Cassius.

Later, in a cab heading toward Greenwich Village, Cassius confessed, at great length, that he certainly must be famous. “Why,” be said, leaning forward and tapping the cab driver on the shoulder, “I bet even you know that I’m Cassius Clay, the great fighter.”

“Sure, Mac,” said the cabbie, and Cassius accepted that as positive identification.

In Greenwich Village, in front of a coffeehouse, be turned to a young man who had a goatee and long hair and asked, “Man, where do all them beatniks hang out?”

In Harlem, after a stroll along Seventh Avenue, Cassius paused in a tavern, and some girl there knew who he was, too. She came over to him and twirled his gold medal in her fingers and said that she wouldn’t mind if Cassius took her home. We took her home, the three of us in a cab. We stopped in front of her home, a dark building on a dark Harlem street, and Cassius went to walk her to her door. “Take your time,” I said. “I’m in no hurry. I’ll wait with the cab.”

He was back in 30 seconds.

“That was quick,” I said.

“Man,” he said, “I’m in training. I can’t fool around with no girls.” Finally, deep into the morning, we wound up at Cassius’s hotel room, a suite in the Waldorf Towers, courtesy of a Louisville businessman who hoped someday to manage the fighter. We were roughly halfway between the suites of Douglas MacArthur and Herbert Hoover, and Cassius knew who one of them was.

For an hour, Cassius showed me pictures he had taken in Rome, and then he gave me a bedroom and said goodnight. “Cassius,” I said, “you’re gonna have to explain to my wife tomorrow why I didn’t get home tonight.”

“You mean,” said Cassius. “your wife knows who I is, too?”

He was still as ebullient, as unaffected, as cocky and as winning as he had been as an amateur. He was as quick with a needle as he was with his fists.

A few months later, after he turned professional, I traveled to Louisville to spend a few days with Cassius and write a story about him. In those days, we couldn’t go together to the downtown restaurants in Louisville, so we ate each night at the same place, a small restaurant in the black section of town. Every night; Cassius ordered the same main course, a two-pound sirloin, which intrigued me because nothing larger than a one-pound sirloin was listed on the menu.

“How’d you know they served two-pound steaks?” I asked him the third or fourth night.

“Man,” he said, “when I found out you were coming down here, I went in and told them to order some.”

In the few months since Jack Dempsey’s, Cassius had discovered the magic of expense accounts.

But he was still as ebullient, as unaffected, as cocky and as winning as he had been as an amateur. He was as quick with a needle as he was with his fists. One afternoon, we were driving down one of the main streets of Louisville, and I stopped for a traffic light. There was a pretty white girl standing on the comer. I looked at her, turned to Cassius and said, “Hey, that’s pretty nice!”

Cassius whipped around. “You crazy, man?” he said. “You can get electrocuted for that! A Jew looking at a white girl in Kentucky!”

In 1961, his first year as a professional, while he was building a string of victories against unknowns, Cassius came to New York for a visit with his mother, his father and his younger brother, Rudolph. Rudy was the Clay the Louisville schoolteachers favored; he was quiet, polite, obedient. Later, as Rahaman Ali, he became the more militant, the more openly bitter, of the brothers.

I took the Clays to dinner at Leone’s, an Italian restaurant that caters partly to sports people and mostly to tourists. To titillate the tourists, Leone’s puts out on the dinner table a huge bowl filled with fruit. Cassius took one look at the bowl of fruit, asked his mother for the large pocketbook she was carrying and began throwing the fruit into the pocketbook. “Don’t want to waste any of this,” he said.

The first course was prosciutto and melon, and Cassius recoiled. “Ham!” he said. “We don’t eat ham. We don’t eat any pork things.” I knew he wasn’t kosher, and I assumed he was stating a personal preference. Of course, Muslims don’t eat pork, and perhaps his Muslim training had already begun. I still suspect, however, that he simply didn’t like pork.

After dinner, we went out in a used Cadillac Cassius had purchased with part of the bonus he received for turning pro (sponsored by nine Louisville and one New York businessmen, all white), and Cassius asked me to drive around town. On Second Avenue, in the area that later became known as the East Village, I pulled into a gas station. It was a snowy night, and after the attendant, a husky black man, had filled the gas tank, he started to clean off the front window. “Tell him it’s good enough, and we’ll go,” I said to Cassius.

“Hey, man,” Cassius said. “It’s good enough, and we’ll go.”

The big black man glowered at Cassius. “Who’s doing this?” he said. “You or me?”

Cassius slouched down. “You the boss, man,” he said. “You the boss.”

The attendant took his time wiping off the front windshield and the back. “Hey, Cash,” I said, “I thought you told me you were the greatest fighter in the world. How come you’re afraid of that guy?”

“You kidding?” said Clay. “He looks like Sonny Liston, man.”

During the middle 1960s, when Cassius soared to the top of the heavyweight division, I drifted away from sports for a while, covering instead politics and murders and riots and lesser diversions. I didn’t get to see any of his title fights, except in theaters, and of course, I didn’t see him. But our paths crossed early in 1964; by then, as city editor of The New York Herald Tribune, I was very much interested in the Black Muslim movement. At first, I didn’t know that Cassius was, too.

Through a contact within the Muslim organization, I learned that Cassius, while training in Miami for his first title fight with Sonny Liston, had flown to New York with Malcolm X and had addressed a Muslim rally in Harlem. As far as anyone knew, that was his first commitment to the Muslims, although he had earlier attended a Muslim meeting with Bill White and Curt Flood, the baseball players (all three attended out of curiosity), and he had been seen in the company of Malcolm X (but so had Martin Luther King).

The words didn’t make any difference: the actions did. He had taken a dangerously costly step because of something he believed in.

When the Herald Tribune decided to break the story of Clay’s official connection with the Muslims, I tried to reach him by telephone half a dozen times for him to confirm or deny or withhold comment on the story. I left messages, explaining why I was calling, and I never heard from him. The story broke, and I heard from mutual acquaintances that Cassius was angry.

The first time I saw him after that—by then, he had adopted the name Muhammad Ali—he was cool, but the next time, in St. Louis, where he was addressing a Muslim group, he was as friendly as he had ever been. He quoted Allah, he paid tribute to the Honorable Elijah Muhammad yet he still answered to the nickname, “Cash.” He even insulted me a few times, a sure sign that he was no longer angry.

He had been stripped of his heavyweight title, and he was fighting through the courts his conviction for refusing induction into the armed forces. I could see him changing, but it was never the words he mouthed that signified the change. His logic was often upside-down, his reasoning faulty, and yet, despite that, he had acquired a new dignity. The words didn’t make any difference: the actions did. He had taken a dangerously costly step because of something he believed in. I might not share his belief or fathom the way be arrived at that belief, but still I had to respect the way be followed through on his beliefs, the way he refused to cry about what he was losing.

Yet it was during this period, when I sympathized with his stand, when I found that some segments of the sportswriting world were exhibiting more venom, more stupidity and more inaccuracies than I had thought even they were capable of, that Muhammad took the only step of his career I can really fault. He turned his back on Malcolm X.

I don’t know the reasoning. I don’t know why he chose Elijah Muhammad over Malcolm X in the dispute between the leader of the Muslims and his most prominent disciple. I can’t, therefore, say flatly that he made the wrong choice, even though I believe he made the wrong choice; Malcolm was a gifted man, an articulate and compassionate man. But I can say that Muhammad showed, for the one time in his life, a totally brutal personal—away from the ring—side. It is brutal to turn on a friend without one word of explanation, without one word of regret, with only blind obedience to the whims of a leader. I have tried, since then, to bring up the subject of Malcolm X with Muhammad Ali several times, and, always, he has tuned out. His expressive face has turned blank. His enthusiasm has turned to dullness. Maybe he is embarrassed. He should be.

During Muhammad’s 43 months away from the ring, I bumped into him occasionally and found him still to be the only professional fighter who was personally both likable and exciting. (Floyd Patterson and Jose Torres, for example, are likable, but not often personally exciting; Ingemar Johansson was exciting.) At one point, David Merrick, the theatrical producer, professed an interest in sponsoring a legal battle to get Muhammad back his New York State boxing license; Merrick wanted to promote an Ali fight in New York for a worthy cause, which was not, in this case, David Merrick.

I arranged a meeting between the two, and Muhammad swept into Merrick’s office and stopped, stunned by the decor, the entire room done in red-and-black. “Man,” said Muhammad, “you got to be part-black to have a place like this. You sure you ain’t black?”

It was the only time I ever saw David Merrick attempt to be charming.

The legal fight never materialized, not through Merrick, and Muhammad continued his road tour, speaking on college campuses, appearing in a short-lived Broadway play, serving as a drama critic, reviewing The Great White Hope for Life. One night, I accompanied him to a taping of The Merv Griffin Show—he was a regular on the talk-show circuit—and during the show, outlining his Muslim philosophy, he spoke of his belief in whites sticking with whites and blacks with blacks.

Afterward, as we emerged from the studio, he was engulfed by admirers, calling him “Champ” and pleading for his autograph. He stopped and signed and signed and signed, still soaking as happily in recognition as he bad almost a decade earlier, and finally—because he was late for an appointment—I grabbed one arm and my wife grabbed the other and we tried to shepherd him away. He took about five steps and then looked at my wife and said, “Didn’t you hear what I said about whites with whites and blacks with blacks?”

She dropped his arm and Muhammad laughed and danced away, like a man relishing a role.

In the fall of 1969, when the New York Mets finished their championship baseball season in Chicago, Muhammad and I and Tom Seaver had dinner one night at a quiet restaurant called the Red Carpet, a place that demanded a tie of every patron except the dethroned heavyweight champion.

The conversation was loud and animated, dominated by Muhammad as always, and about halfway through the meal, pausing for breath, he turned to Seaver and said, “Hey, you a nice fella. You a sportswriter?”

When we left the restaurant, we climbed into Muhammad’s car, an Eldorado coupe, pink with white upholstery, with two telephones. Two telephones in a coupe! “C’mon, man,” he said to Seaver. “Use the phone. Where’s your wife? In New York? Well, call her up and say hello.”

“This is the baddest cat in the world, and I’m with your husband and five hookers.”

Seaver hesitated, and Muhammad said, “I’ll place the call. What’s your number?”

Seaver gave Muhammad the phone number, and Muhammad reached the mobile operator and placed the call, and when Nancy Seaver picked up the phone, she heard a deep voice boom. “This is the baddest cat in the world, and I’m with your husband and five hookers.”

Nancy Seaver laughed. Her husband had told her he was having dinner with the champ.

Later, we returned to my hotel room, and after a few questions about his physical condition, Muhammad took off his suit jacket and his shirt and began shadow-boxing in front of a full-length mirror. For 15 straight minutes, he shadow-boxed, letting out “Whoosh, whoosh,” the punches whistling, a dazzling display of footwork and stamina and sheer unbelievable speed, all the time telling Seaver his life story, his religious beliefs and his future plans.

“I never saw anything like that in my life,” said Seaver afterward.

Neither had anyone else.

A few weeks later in the fall of 1969, Muhammad appeared as a guest on a sports-talk show, a show in which I served each week as sub-host and willing straight man for Joe Namath. For each show, we had one sports guest and one non-sports guest, and that week Muhammad was joined by George Segal, the actor.

After the interview with Muhammad, Joe and I began chatting with Segal, and the subject of nudity came up. Segal had just finished filming a nude or semi-nude scene with Barbra Streisand in The Owl and the Pussycat. As the conversation about nudity began, Muhammad visibly stiffened. “What’s the matter?” Joe said. “How you feel about that, Muhammad?”

Muhammad’s reaction was immediate. He was affronted and insulted. He was a minister, and he did not know that the show was going to deal with such blasphemy, and he was about to walk off the stage rather than join in, or even tolerate, such talk.

“Aw, c’mon,” Joe said.

Muhammad sat uncomfortably through the remainder of the show, punctuating his distaste with winces and grimaces. It made for a very exciting show, and when it was over, Joe and I both sort of apologized to Muhammad for embarrassing him. “I gotta act like that,” Muhammad explained. “You know, the FBI might be listening, or the CIA, or somebody like that.”

He is now 29 years old. He has been a professional fighter for a full decade, and he has fought 31 times, and he has never been beaten.

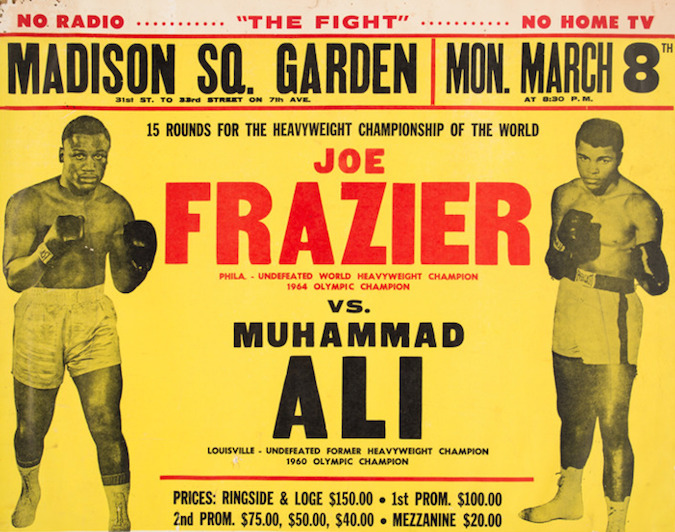

On March 8, he faces Joe Frazier, who has also never been beaten, who is younger, who is considerably more single-minded. Logic is on Frazier’s side. Reason is on Frazier’s side.

But logic and reason have never been Muhammad Ali’s strong suits. They were never Cassius Clay’s either. His game always will be emotion and charm and vitality and showmanship.

Eight weeks before the night of the Frazier fight, the telephone rang in my bedroom late one night. I picked it up. “Hello,” I said. “The champion of the world,” said the caller. “I’m back from the dead.”

I hope so. The man-child should be the heavyweight champion of the world. It is the only role he was born to play.