It was all of two o’clock on a sultry, Thursday afternoon, and Harry Crews was poured into a corner booth at an ersatz nautical bar in Gainesville, Florida, called the Winnjammer. Bits of sailing rigging were scattered about. The place was as dark as the hold of an Eastern European freighter. Light from a flickering wall lamp played upon Crews’ face, and there was a shock in seeing him, discernably electric, as if he were stripped of psychic insulation like a wounded animal that has retreated to its lair. “The craziness is in me,” he was growling. “I’m self-destructive, masochistic.” He was slouched into the booth, and one of his legs, crippled from childhood polio, hung limply to the floor. His large, brutal torso, fitted into a decaying mauve sweatshirt, coiled lazily. His massive head, eyes set deep into the brow, turned on a thick neck around which he wore a silver and turquoise chain. “My private life is a shambles,” he said. The voice was almost indiscernible, lost in a glass of Scotch and milk. “I get into trouble. I can’t cope. I louse things up, wreck cars, lose money. But a fictional world—I can make it do what I can’t do with my own life.”

Here at the Winnjammer, Crews was fighting to gain control of himself. He had just endured a long, hot drive back to Gainesville from Ashburn, Georgia, where his mother was ill with appendicitis. He was trying to pull his mind together before going home to finish an article about jockeys for Sport magazine. Facing him at 7 p.m. was the initial meeting of a quarterly fiction-writing class he teaches at the University of Florida. In the back of his mind, hanging like a millstone, was the thought of the writing he still needed to do on his first work of nonfiction: A Childhood: The Biography of a Place. Scheduled for release in the fall, it is to be a dissection of past and present in Bacon County, Georgia, Crews’ birthplace. It will be his ninth book, and it follows a string of novels that began appearing yearly in 1968 with the publication of The Gospel Singer. Whether the new work will come from what could be called Crews’ world is difficult to say. Crews’ world is hard to understand. He doesn’t comprehend it completely. However, an observation that Flannery O’Connor made about her own fiction could just as well apply to his: It is in the extremity of evil circumstances that the possibilities of grace are more nearly perceived.

“Oh man, man. I feel like I’m gonna die,” Crews was saying. “My mama just worries, worries, worries. I had to go up there to check on her because a son has got to do what he feels he’s got to do.” A second Scotch and milk was in his hands. “I may die, though. Damn drive.”

Lighting a Marlboro, the writer backed up from the thought of his demise. “I ain’t gonna die, but damn if I don’t feel like it. Bring me another of the same and less milk,” he called to the barmaid.

Harry Crews’ novels abound with the extremities of evil circumstances, the products of evil circumstances. There is Joe Lon Mackey, protagonist of his most recent effort, A Feast of Snakes, which is set in Mystic, Georgia, at the time of the town’s annual rattlesnake roundup. Joe Lon is a college-caliber football player left with nowhere to play because of poor high school grades. He re-channels the brutality his coaches encouraged in him by blowing away a number of acquaintances with shotgun blasts.

Then there is the Gospel Singer, in the novel of the same name, a golden sheep born from the fold of a depraved white trash family in Enigma, Georgia. The Gospel Singer has a honeyed voice that has allowed him to escape the insularity of his hometown. He returns to sing at one last tent revival and ends up getting hanged from a tree. The people of Enigma perceive that he’s a charlatan and exact their vengeance.

Appearing in almost all of Crews’ novels are midgets, people without legs, the lame and the halt. There are also crowds in every book—milling, destroying, and running awry with the license granted to those in large groups where anonymity triumphs over responsibility.

“I don’t think of myself as a Southern writer. I don’t think any novelist of any consequence wants an adjective in front of the word novelist. You don’t want to be a gothic novelist or a black-humor novelist. You just want to be a novelist.”

A fresh drink in hand, Crews took a shot at explaining his literary landscape. “I’m not really a product of William Faulkner,” he said, his voice at once filled with jazz and Georgia. “Graham Greene has influenced me more than any other writer. People are always talking to me about being a Southern novelist, about being out of the Southern tradition, and all of that crap. All I can say to them is I’ve lived in the South all my life. I was born and raised in Bacon County. But I don’t think of myself as a Southern writer. I don’t think any novelist of any consequence wants an adjective in front of the word novelist. You don’t want to be ah, I don’t know, a gothic novelist or a black-humor novelist. You just want to be a novelist. It’s true that a writer is told by a lot of stupid people, like English teachers, to write about what you know. But that’s bull. You write about murder, and you never killed anybody. You write about a woman, and you haven’t been a woman, and on and on. What English teachers mean, I hope, and they probably don’t, but what they should mean is that to write and write well you have to be on incredibly intimate terms with the manners of a people, the culture of a part of the country.”

That, however, was it for now. After tipping his glass up over his nose and draining it, Crews declared, “I’m splitting.”

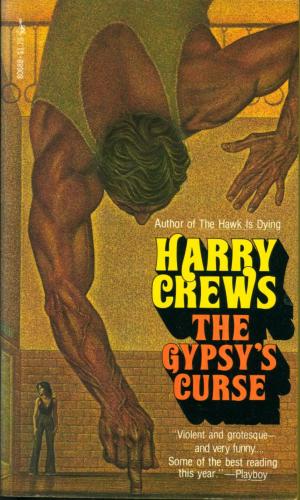

Writers like Harry Crews run the risk of not just being mythicized but stigmatized. Already, the cultural elite have consigned him to a place that one critic said was beneath the dark root of the Southern literary tradition. Because Crews writes about people who on the face of it are freaks and evil interlopers—Jean Stafford called his bailiwick “a Hieronymous Bosch landscape in Dixie”— he is regarded primarily as a purveyor of the abnormal and the gut-wrenching. Obsession, violent, grotesque, gratuitous, bizarre, macabre, harrowing, and wild—these are the labels reviewers tack to Crews’ fiction. “I don’t even read that crap anymore,” the writer will bellow. “It’s too hard to write, and if you read enough of that, you flip and lose your confidence. It does happen.”

Although Crews has received his share of plaudits, the general perception holds that he is nuts, that he writes about nuts, and that his work is rife with uncalled for ugliness and perversity. The consensus is that he sits at his 1929 Underwood typewriter in his stultifying stucco rental house in Gainesville and busies himself with creating ever more bizarre scenarios to be marketed to the freak-reading public. Even his friends promote this view. Playboy, where Crews’ articles appear frequently, labeled him its “resident weirdo.” Esquire, for which Crews writes a monthly column called “Grits,” created a standing logo that suggests the cracking skin of the Marvel comic book character the Thing. The paperback editions of Crews books fall all over themselves to promote the transgressive nature of the writer’s vision. The jackets are adorned with everything from paraplegics in tank tops rotating on their middle fingers to sexy karate fighters in bikinis.

Then there are the hard facts of Crews’ own life. His behavior has been so outrageous that many accuse him of being drunk on machismo. Already this year, he has been forced into an out-of-court settlement with a man whom he says “leaned on me too hard, just wouldn’t let me out of there without going back to the parking lot and then, what could I do? When it’s gone that far, there’s nothing to do but go on with it.” Anyway, Crews ended up breaking the man’s hip in the ensuing brawl outside a Miami lounge. There have been other incidents as well. He was thrown into jail in St. Augustine after a ruckus at an establishment called the Slipped Disc Disco. While in Tulsa, Oklahoma, reporting an Esquire story about allegations of sexual impropriety involving evangelist Garner Ted Armstrong, Crews took up for a Tex-Mex in a fight with an immigration agent and was again jailed. The writer’s day-to-day existence seems as extreme as his work.

Jed Smock was gyrating like a drunken top on a worn spot of grass in a quadrangle near Harry Crews’ office in the gothic fine arts building at the University of Florida. Smock, a well-known Gainesville street evangelist who dresses in white suits and embellishes the impending doom of the Old Testament with his own febrile imagination (“Do you think those people on the 747s that collided the other week in the Canary Island knew they were going to die? Did they know Jesus? Will you know Jesus if you are called tonight?”), considers the Gator student body to be his personal flock. His admonitions wafted up to Crews’ window on this Friday morning as they do most every day.

It was just a little past eight, and Crews was well into his third large Styrofoam cup of Krispy Kreme coffee. The previous night had been taxing. It began with a two-hour lecture to his fiction-writing class and ended with a drop-in friend curling up with a stun-gun in the living room. A never defined threat—an angry husband, an unpaid drug dealer—was looming, and the writer felt the need for protection. Now, however, he was shaking all that off, slurping coffee, smoking cigarettes, and stoking his nerves. Outside, Smock was telling a group of Krishna consciousness devotees that they and their saffron robes were going to burn eternally.

“I think precisely what people mistake in me as being macho, that thing in me that wants to get as far on the edge as I can of anything that I can, the thing I like to call getting naked, is my need to keep myself going as a writer.”

“God, I don’t know. I don’t know,” Crews mused. “One of the things that writers live with is the terror—fear—that they’re not going to be able to write a book. And if you write one, you’re scared that you’re not going to be able to write another one or that if you do write it, it’s going to be terrible. And writers who are truly writers, that’s about all they got to live for. It’s what keeps them together. It gives them something to hold onto. William Inge, the playwright out in Los Angeles who wrote Picnic, killed himself because he couldn’t get any work anymore.”

Crews finished his coffee and grunted. “I think precisely what people mistake in me as being macho, that thing in me that wants to get as far on the edge as I can of anything that I can, the thing I like to call getting naked, is my need to keep myself going as a writer. You can’t find out about a thing—well, you can find out about a thing vicariously and you can find out about it by reading a book—but you can’t find out about a thing as well as you can when you’re naked and vulnerable to the experiences of the world.

“And that’s the only reason that I can live more or less in a university community and still not write academic novels. I go out into the world and do whatever I do. Now people can just say what they want to say. I don’t think anybody who’s ever met me or known me for any length of time, intimately, would say that I go out and do these things, this machismo stuff. I’m just out there, and if you’re out there long enough, things happen to you. And then you write about them.

“There is a cost. There is. My gig is to get naked, but guys make me out as a brawler and a drunk, and sure, I howl sometimes, just like anybody, I howl.

“What I wonder about, however, are things like when I went into this bar last week and a guy I don’t know from Adam asks me about the time I was out at the Blue Pine and got into a fight with a cue stick with some guys. I say to this character, ‘That never happened, man. How do you think I get any work done, hunh?’ That’s the thing they don’t realize. People think I’m always lying in some gutter someplace, sleeping something off. There are times I am, but not that often. I try to take reasonably good care of my talent. I figure I’m just hitting my stride. A good writer ought to be able to get 22, 24, 25 books in a career. After all, no matter what anyone says, we’re just trying to get through this thing, trying to have something to do until we die.”

Harry Crews has paid a stiff price to get this far. Born into horrific poverty at the height of the Depression, he began writing fiction when he was five years old about the models in Sears, Roebuck catalogs. “Those models were always perfect, and my home life was pretty awful.” In spite of his polio-damaged leg, Crews talked his way into the Marine Corps at age 17. He stayed three years, leaving to enroll at the University of Florida, where he studied fiction writing under Andrew Lytle. He was, Crews said, his great teacher. Lytle had been a member of the Vanderbilt University fugitive group of writers, which included Robert Penn Warren and John Crowe Ransom, and he saw potential in the upstart from South Georgia.

When Crews left the university, he took an unlikely job as a seventh grade English teacher at a junior high school in Jacksonville. It was 1962. There, living with his young wife and a son who would later drown, the budding novelist made his most important investment into learning how to write.

“I wrote a novel that year. What I did was take Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair, and I reduced the damn thing to numbers.” Crews had gone out for still another cup of coffee, and he spilled it on his desk with a sweeping punch from his right fist as he warmed to the story. “Nerves,” he observed, “Pure nerves.” Then he picked right back up. “Anyway, I determined how many characters Greene had, how much time was in the book—present time and past time and the time of memory and of flashback, all of it. I found out how many cities were in the book and how many buildings and how many rooms in the buildings and how many transitions. And I pinpointed the climaxes, where action turned, found what pages they were on. I read that book until it was dog-eared and was coming apart in my hands.

“After that, I said, ‘I’m gonna write a novel with the same number of scenes and on and on as are in The End of the Affair.’ I knew I was going to waste a year—but it wasn’t a waste—and I knew the end result was going to be a mechanical, unreadable novel. But I was trying to find out how you do it. I wrote it, and it ended up being the piece of crap I knew it would be.

“I mean, I ate that damn Graham Greene book, literally ate it. And after I wrote mine, I didn’t let anybody read it but Mr. Lytle, and he gave it back to me and said, ‘Well, son.…’ He was a hard taskmaster. But it didn’t matter. Because of that year I knew how it was done, and I went on from there.”

It was mid-morning, and Crews was in need of alcoholic sustenance. The Gainesville bars opened at eleven, so donning a black beret, he limped out from his office to make the drive to the house of his ex-wife, Sally, for a couple of vodka tonics. After hoisting himself into his silver van, Crews jammed a tape of Randy Newman’s Good Old Boys into an eight-track player and pulled onto the blistering macadam of the highway. Driving loosened him, as if it worked the coffee out of his system.

“Yeah, it’s very difficult for me to talk about. It’s very difficult for me to intellectualize on all the work I’ve done,” Crews said, “but it’s easy to do about the work someone else has done.” As he weaved in and out of traffic, Crews hummed along with “Kingfish,” Newman’s song about Huey Long.

“For instance, people have written that there is a midget in my first three novels. When I gave a copy of This Thing Don’t Lead to Heaven, my third novel, to Sally, she said, ‘You don’t, do you, intend to make a career out of midgets?’ And that was the first time it ever occurred to me that there were midgets in my first three books. There’s Jefferson Davis Munroe in This Thing Don’t Lead to Heaven, Foot in The Gospel Singer, and Jester in Naked in Garden Hills.

“This thing I’m writing for Sport about jockeys – I was down in the jockey room at the race track working on it, looking at all them little people, and they don’t walk, they tick, like a watch. They’re fine. I say in the piece that they are perfect of their kind. They are the absolute essence of what is needed to do what they do, which is ride thoroughbreds.”

Harry Crews never relaxes long. The talk about midgets had rekindled his animosity toward critics. He was all wound up again, so much so that he nearly missed the turn from one of Gainesville’s main drags onto the shady street that leads to his ex’s home. “There are these guys,” he was saying, almost spitting the words, “who say I write gratuitously about freaks. Some guy at the Atlanta papers said that in a negative review of The Gospel Singer. I wonder about that guy, if he’s ever written anything himself. He said that I was a terrible writer and that you’d never hear from me again, that I’ll never write another book.

“Anyway, there’s a guy who has his head on wrong. Some people never get over that kind of criticism. I’m not saying this to be self-serving, but to be a writer and to sustain yourself for a long period of time, you need raw courage. You have to say to the world: ‘OK. Say what you want about me. And I’m still gonna write and I’m gonna write the way I want to write, and I’m not gonna write books to satisfy you.’

“And if they’re gonna say I gratuitously write about freaks and violence, let them go ahead and say it. I have a helluva lot of compassion and sympathy for those people who, as I said about Foot in The Gospel Singer, are special under God—or special people.”

Crews had now stopped in the driveway of Sally’s pretty ranch house, but he wasn’t finished. “See, I can walk around and I’m not going to get any static. People will look at me and no one is struck by how ruined I am. I can think dreadful things, have dreadful notions in my mind and no one is going to know. But a guy who is three feet tall is going to have to deal with being three feet tall every day. And every time he turns a corner, he looks at a guy and he sees his own predicament in that guy’s eyes.

“I write out of this kind of outrage. And to write about the violence and stuff I write about, you’ve got to be angry.”

“To write about one thing you have to talk about another thing, and that’s the whole nature of fiction and poetry. You can say more about what the world out there calls normal by dealing with what the world calls abnormal. This is what I do.

“The reading public bothers me, though. They don’t want to read about the blood and bones and guts of an issue. They want to read about something they’re not going to have to think about, and if it does hurt them as, say, Love Story does, it won’t last very long. What has happened in this country is a failure of the imagination.”

Crews eased himself out of the van and began fumbling around in his pocket for a key. Finding it, he shoved his beret low on his forehead and shuffled to the side yard, where a brick doghouse provides a home for Brutus, his black mastiff. “I write out of this kind of outrage,” he was saying. “And to write about the violence and stuff I write about, you’ve got to be angry. People wouldn’t understand it if I said I was a moralist. They’d think I was some academic dude holed up with a bunch of facts and books who didn’t live in the real world. But to write out of my kind of outrage, you’ve got to be a stomp-down, hard-core moralist.”

Crews had begun to tease Brutus. When the dog growled at him he growled back. Soon enough, man was barking at dog and dog was barking at man. The encounter conjured a scene from The Gospel Singer, where a character named Didymus contemplates throwing himself to a massive beast.

Didymus said: “Go into strange lands where people have never heard of you and tell them things they do not want to hear and cannot understand. If you are lucky, they will kill you and eat you … or throw you to vicious dogs. That is the way to God, righteousness, and the moral life.”

This story is collected in A Man’s World.

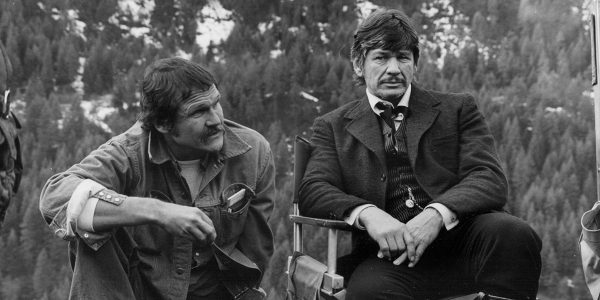

[Photo Credit: University of George Press via Ted Geltner’s definitive biography, Blood, Bone and Marrow.]