In an interview after winning the Nobel Prize, Saul Bellow contended that most people don’t pay any mind to writers, and his assessment struck me as correct.

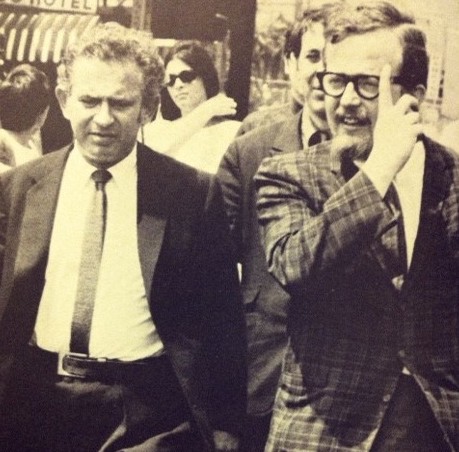

This fact was bulldozed home to me in 1969 when, as a literary naif, I “managed” Norman Mailer’s mayoralty bid (he stopped short of suffocating me with a pillow when it seemed to him blocked his crown). That year, The Daily News, the city’s proletarian paper, conducted a poll on the name recognition of the candidates.

Now I must remind you this was the year Mailer won both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer for his dazzling The Armies of the Night. Add to this that Norman is not known as a shy, retiring writer. Indeed, he could match the accolade John Ford paid to Barry Fitzgerald: “He could steal a scene from a dog.”

But nonetheless, when the poll results were tabulated, 60 percent of those questioned didn’t even know who Mailer was. And to boot, many of those who did recognize his name associated it not with literature but with carousing and domestic squabbles.

This cinched the case for me, but apparently many of my cohorts have not yet gotten the word. From the plethora of pieces I have read lately by writers bemoaning the travails of their craft, the functioning and dysfunction of their heads and regions south, their work habits or lack of same, many of my fellow travelers must be under the illusion that their lives are as interesting to the general public as Mary Hartman’s.

But before I’m branded a quisling for the vulgar herd, I confess a degree of sympathy for the writer’s plight. There are editors to contend with, and sometimes I believe that breed invented Maxwell Perkins to give themselves cachet. Also, there are the coroners of the trade, the reviewers (whom I refuse to call “critics,” since it would grant them the company of Wilson and Trilling). This species seems unhappier than writers: they endlessly look for “uplifting” books or those with solutions and finally find themselves applauding such tomes as “I’m Okey, You’re Dokey.” Then there’s money—the heart of the matter—but space prohibits. And alas, there is the dread bogeyman, Writer’s Block.

In an interview after winning the Nobel Prize, Saul Bellow contended that most people don’t pay any mind to writers, and his assessment struck me as correct.

This unwelcome phenom seems to occur when writers feel they must create the “consummate” book. In youth this idea was so touching the memory pains, but, carried into maturity, it is a bloated conceit. Ah, to change the world! To make unruly humans behave like trained puppies who come to your papers for relief! I know the impulse well. Inside this fey Irish heart lurks a Prussian stationmaster with foreboding schedules to be obeyed.

The obligatory over, let’s explore what’s left of these literary laments. To start, the writer is not alone in his unhappiness, since a recent survey showed that 80 percent of all Americans are unhappy with their work, the difference being these people know precisely what they dislike while writers suffer under some vague fugue—a legionnaire’s angst. They tortuously toss and turn that they might be “selling out,” a tack I wouldn’t touch for fear no one would notice the crossing of that Rubicon.

A while back, my mother, who has done physical work all her life, called me and in the course of the conversation complained about exhaustion. I had just completed a long magazine piece and replied that I was tired too. She snapped, “What the hell are you tired for—you don’t have a job.”

My ego was more perforated than Bonnie’s and Clyde’s in the final frame, and I was about to give the old girl a word count for the previous few days, until I realized the wisdom of her cut.

Indeed, I don’t have a job in the conventional sense. There are few “musts” in the writer’s life. The imperatives of rising, checking in, spending specified time, traveling to and fro, and set accomplishments (blowing deadlines bespeaks genius) are not mandated by an outside source. By these lights it’s not shocking that most people pay no mind to us.

Further none of these laments mention the spectacular drinking time that comes with the writer’s life. Like dreaming, a shoe shine and a smile, it comes with the territory.

Drinking occasions are appropriate when the writer is “blocked” or is in his “creative throes” or just has completed a long work period or been praised or panned by the reviewers. Better yet, if you’re not going through one of these stages yourself, you’re allowed to babysit with a friend who is. What other profession looks kindly on sympathetic elbowbending?

So while the malaise business is fine to fob off on literary quarterlies and the kids in creative writing courses, a little reality should creep into the writer’s world—such as mornings when the mailman arrives at the door with his eyes frosted over while yours are caked with sleep (to be at home during the recent cold snap had to be worth a kilo of angst). Or when the phone rings at the ungodly hour of 10 A.M. and you have to run the range of Nellie Melba’s vocal exercises to deceive the outside world of your sloth. And try to understand the disdainful sneer of the exterminator on those odd Wednesdays, the sneer that says if the vermin have the grace to be and about, so could

When the blahs hit my fellow writers I suggest they concoct an errand that will force them to board the subway at 8 A.M. and return on that same conveyance at 5 P.M. If I am in a self‐pitying mood, this gambit always works. Indeed, upon exiting from the hole, I run to the nearest church and light a candle to thank the Lord for letting me get away with it this long and to implore Him to grant me a few more years.