It’s hard to believe that a great comedy could be made of the blitz, but John Boorman has done it. In his new, autobiographical film, Hope and Glory, he has had the inspiration to desentimentalize wartime England and show us the Second World War the way he saw it as an eight-year-old—as a party that kept going day after day, night after night. The war frees the Rohans (based on Boorman’s family) from the dismal monotony of their pinched white-collar lives and of their street, with its row of semidetached suburban houses; now they have the excitement of the bomb blasts, the dash to the shelters, the searchlights combing the night skies, the stirring patriotic bilge on the wireless, and the equality that’s ushered in with the ration books.

Bill Rohan (Sebastian Rice Edwards) diligently collects shrapnel, and, along with the other eight- and nine-year-old boys, pokes through the ruins, smashing whatever’s left to smash. Boorman lets his characters say the previously unsayable. Bored with crouching indoors during the nightly raids by the Luftwaffe and listening to the shelling and sirens, the 15-year-old Dawn (Sammi Davis), the eldest of the three Rohan children, runs outside for the exhilaration of movement, watches the firefighters at work on a blazing house, and dances in the Rohans’ postage-stamp-size front garden. “It’s lovely!” she calls to Bill as he hesitates on the porch. Seeing something by the curb, he runs out and picks it up—“Shrapnel! And it’s still hot.” He tosses it from hand to hand, cooling it. His mother, Grace (Sarah Miles), suddenly laughs at the sight of the burning house down the street, and is shocked at her own reaction. She calls out, “Come in at once, or I wash my hands of you!” And then, as Boorman writes (the script has been published by Faber & Faber): “A shell bursts right overhead and they duck into the open doorway. The four of them are framed there, looking up at the savage sky where the Battle of Britain rages. Bill watches, enraptured.”

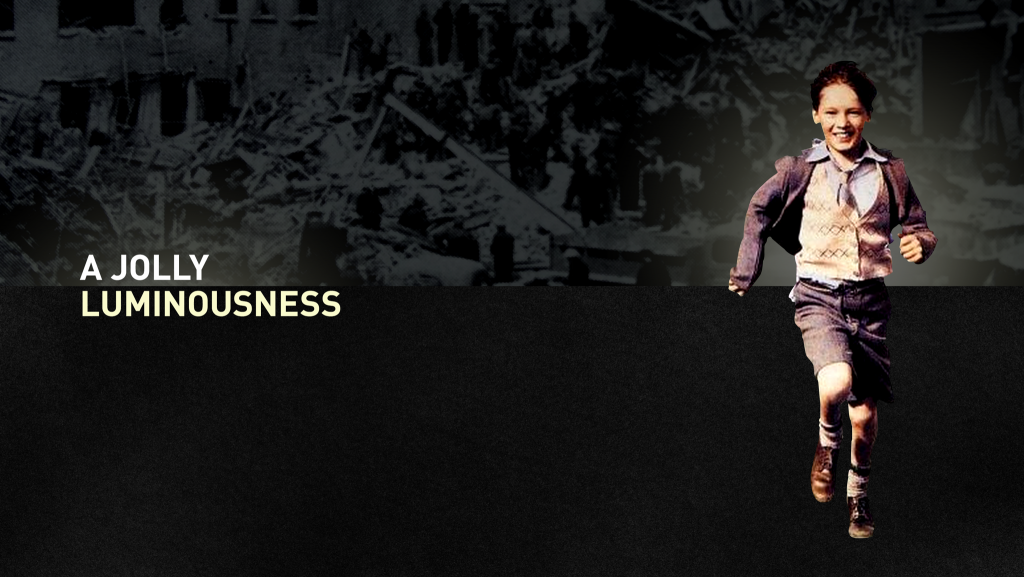

Boorman’s approach makes perfect sense. He doesn’t deny the war its terrors: there’s an astonishing scene where Grace and the two younger children are heading out to the shelter but don’t make it; bright white shell bursts knock them back and fling them about the living room as if they were slow-motion marionettes. Yet he gives everything a comic fillip. Bill and the other schoolkids have to wear gas masks when they go to the school shelter, and the headmaster makes them put their time to use by reciting multiplication tables; exquisitely repulsive sucking-air sounds come out. At one point, when Grace and her kids are at the movies, watching a newsreel of the Battle of Britain, a notice on the screen tells them that there’s an air raid and they should take shelter. As Grace leads them up the aisle, Bill says, “Can’t we just see the end?” Dawn tells him, “They’ve got the real thing outside.” “It’s not the same,” he says. And that’s true for the movie we’re watching: it’s the life that goes on outside the theatre, but selected, heightened, polished. And, in the case of Hope and Glory, life outside has been given an extra dose of good sense—a jolly luminousness.

The picture recalls what Ingmar Bergman tried to do in Fanny and Alexander—to create a whole vision of life out of a man’s memories of what, as a child, he perceived about his family. But, rich as Bergman’s film is, he got bogged down in Gothic fantasies and Victorian conventionality; he’s never at peace with the child’s amoral side. Boorman treats the memories more lightheartedly. So his mother didn’t love his father and they weren’t happy together, but he survived. The war came along and shook things up, and if his father (David Hayman), who was like a shrivelled patriotic schoolboy, tried to escape the sense of shame he felt about slipping down from the middle class to the rootless life of the semis, and enlisted, expecting adventures but finding himself put to work as a clerk-typist—well, at least he got to visit his family. And when that semidetached house—emblem of coal pollution and conformity—burned down (in a “normal” fire that couldn’t be blamed on the Nazis) nobody missed it. Its destruction provided the excuse for Grace and the children to move into her parents’ big, open, ramshackle bungalow on the Thames, where Bill and his six-year-old sister, Sue (Geraldine Muir), could fish and play. And since this was at Shepperton, near the studios that Alexander Korda built, and movie crews frequently worked along the river, Bill could develop the interests that turned him into John Boorman.

The movie is wonderfully free of bellyaching. Grandfather (Ian Bannen) is a gruff, demanding old buzzard who gets drunk at Christmas and subjects the whole clan to his toasts to all the ladies he remembers with lewd satisfaction. But he also instructs Bill in the lore of the river. Now and then, Bill can tease him and get away with it, and when, just hours before the beginning of the fall term, Bill’s grim, dreaded school is bombed and burned out, Grandfather laughs like a cartoon anarchist. It’s as if his and Bill’s dreams had exploded the place. And not theirs alone: arriving for the first day of servitude, the pupils see the bomb debris and riot in the schoolyard. It’s a whoop-de-do celebration, because their holidays will be extended; it’s also an orgy of hatred for the headmaster, who likes to cane kids, raising welts on their palms. He has told them that discipline wins wars; now the bombs have put a stop to his tyranny. That’s the joy of the movie: the war has its horrors, but it also destroys much of what the genteel poor like Grace Rohan have barely been able to acknowledge they wanted destroyed.

Boorman keeps his energy up in all the scenes. He doesn’t get so personal he loses control, and he doesn’t fall into any of his Jungian pits. The many things that could go wrong didn’t; the picture moves along lightly, one incident after another, a collage of memories, dreams, newsreels, old movies, fake old movies. It’s like a plainspoken, English variant of the Taviani brothers’ The Night of the Shooting Stars, which was also the Second World War as seen through the eyes of a child. In that film, the child, grown up, mythicizes her war experiences, converting them into bedtime stories to tell her own child, and Boorman has written that his script began with the stories he told his kids at bedtime. Many of his characters and anecdotes are like archetypes, but they’re grounded in definite, “real” characters and situations. They’re never forced on us; they simply take hold—maybe because we’re always in on the jokes. The picture has a beautiful pop clarity.

Sammi Davis’s dimply, pleasure-loving Dawn is always changing her mind. She wants sex but not love and is furious when she falls for a Canadian jokester soldier with dimples of his own (Jean-Marc Barr). Sammi Davis (she was the blond teen-age prostitute in Mona Lisa, and she’s the blind girl in A Prayer for the Dying) makes Dawn’s bluntness wittily uncouth; she turns just about every line she has into a kicker. And, as Grace’s friend Molly, Susan Wooldridge (she was Daphne Manners in The Jewel in the Crown) has moments when she’s almost as no-nonsense “common” as Dawn. A few of the characters—such as Molly’s husband, Mac (Derrick O’Connor)—don’t have any comic turns and so they don’t add up to much. And not all the performances are dazzling. (Sarah Miles is actressy without being much of an actress.) But you feel that you’re seeing the people with refreshed eyes. Sebastian Rice Edwards’ Bill is everything he should be: funny, tough-minded, open-faced. And although the role of Sue takes less doing, Geraldine Muir is a hilarious little trouper. Her misconstruction of what she sees through the keyhole when she watches Dawn and the Canadian and what she sees when she watches Mummy and Daddy is a small classic.

The picture itself is big—a large-scale comic vision, with 90-foot barrage balloons as part of the party atmosphere. In the opening scenes, kids in a movie theatre are throwing bits of paper at each other, creating a blizzard. Boorman’s touch here is so sure it’s as if he were handing us popcorn, and saying, “Throw it if you want; just have a good time.”

[Image credit: Sam Woolley/GMG]