At the present time the top young American movie actress to emerge in recent years is Jane Fonda. (This is not so impressive as it may sound, because who else is there? Raquel Welch?) Accelerating her pace in the past few years, she has darted back and forth across the Atlantic, making movies in French—La Ronde, La Curée—and in English—Cat Ballou, The Chase, Any Wednesday, Hurry Sundown, Barefoot in the Park. The emphasis in her films is increasingly on sex, and the strategy is to present her as a girl who can’t get enough of it. Put her in any scene with a likely looking young man, and if they’re alone two seconds she starts to unbutton his shirt.

The result is neither the sullen sexual intensity of a Jeanne Moreau nor the teasing lubricity of Brigitte Bardot (although Jane has frequently been referred to in the French press as “the American B.B.”), but more of a rah-rah display of eager enthusiasm, as if sex were being given the old college try. Possibly the reason for this is because Jane Fonda is a terribly nice girl—decent, friendly, polite, kind, generous, thoughtful, loyal—who is trying as hard as she can to exemplify the unabashedly publicized ideals of her husband, Roger Vadim, the French director who achieved a tenuous claim to immortality as the “discoverer” and first husband of Bardot and who has since become regarded as the father of the modem compulsory nude love scene in movies, which he pioneered by directing all his wives and/or mistresses in the buff.

His announced messianic urge is to eliminate all sense of guilt about the human body and all erotic complexes, a not unlaudable aim which possibly would be more attainable if he made better pictures. Head over heels in love, Jane has adopted his philosophy, his way of life, his country, his language. She has industriously and earnestly tackled the process of becoming French in a way that only a spirited and determined American girl would do, with the result that the more French she becomes, the more American she remains. No matter how many torrid cinematic nude love scenes she enacts under Vadim’s guidance, she cannot seem to help giving the impression of a bright, well-bred, innocently larky American girl who has gone to the right schools (which she did: Emma Willard and Vassar) and is simply too classy and too hygienic to get down into the muck and guts of raw emotion.

She is further handicapped by another drawback not customarily exhibited by most actresses or, indeed, many other women, namely, a total lack of vanity and bitchiness. Her best friend, Brooke Hayward Hopper (daughter of Leland Hayward and Margaret Sullavan), whom she has known since childhood, says of her, “She’s the only girl I know who’s not a bitch”; while Michael Caine, who starred opposite Jane in Hurry Sundown, told me, “She has the quality of humility, a humility I’ve seldom met before, especially in actresses.”

Most top Hollywood stars whom I have observed filming on location lead elaborately cosseted lives, with studio myrmidons leaping to anticipate their most arbitrary whims. It is typical of Jane that nothing could have been further from the fabric of her life during the six months she spent in Italy making the movie version of Barbarella, a randy French comic strip for adults (sale to minors is prohibited), filmed in English, with Vadim directing and Dino de Laurentiis producing for Paramount. The title role is that of a well-stacked interplanetary adventuress of the future, given to stripping off all her clothes at the drop of a space helmet, who leads a promiscuous sex life in extraterrestrial regions. This part, of course, is played by Jane, who says of the film, “It’s pop art, sex and satire—ideal for Vadim.”

I drove out to see her in her rented villa on the outskirts of Rome, on the Appia Antica, sometimes called “Millionaires’ Row.” The villa turned out to be in an isolated country spot, almost at the end of the road, a beautiful, centuries-old stone castle set amid cypresses and pines, with no heat, no hot water at the time I was there (the tank had exploded), an elevator that got stuck between floors with guests in it, lights that kept going out, and rats all over the place. The rent was $1,500 a month. They chose this particular estate because Vadim lived there with Annette (his second wife) in 1960, when he was directing her in an easily forgettable French movie about vampires. He wanted to stay there again, and whatever Vadim wants, Jane gets for him, from a farmhouse in France to a Ferrari.

I arrived at the villa at one o’clock, the time I had been told to come for lunch, only to find a situation that was, to use Jane’s own words, “like mass hysteria.” Thirteen people were expected for lunch and eight for dinner. Nathalie, Vadim’s nine-year old daughter by Annette Stroyberg, and Christian, his three-year-old son by Catherine Deneuve (who did not marry Vadim but has since married the English photographer David Bailey), and their young Scottish nanny were staying at the villa together with Jean-Claude Forrest, the artist who created Barbarella, his wife, Vadim’s male French secretary, and Kamilla, Annette Stroyberg’s dishy half-sister. Serge Marquand, brother of Vadim’s long-time intimate friend, the actor Christian Marquand, was also a house guest but was leaving that afternoon, to be replaced by Claude Renoir, the cameraman, who was arriving sometime during the night.

All told, counting myself, there were fourteen people sleeping in the villa; three more were moving in the next week (a French scenic designer, an English actor, and an American script-writer), and future expected house guests included Vadim’s mother, Jane’s brother, and Jane’s friend Brooke Hayward (whose mother, Margaret Sullavan, was Henry Fonda’s first wife). To cope with this teeming household, Jane had a domestic staff of three: a cook, a maid, and a butler. (When Elizabeth Taylor rented her villa on the Appia Antica, she had a staff of fourteen.) It didn’t help much that Jane’s maid and butler, a married couple, had never worked as servants before, the husband previously having been a member of the carabinieri (military police). To complicate matters further, no sooner had I arrived than Vadim suddenly decided to fly to Saint-Tropez the next morning, taking with him six or seven people, including Jane and the children, for the weekend.

Lunch was more than two and a half hours late. We were all waiting for Vadim, who stayed in his study, working on the Barbarella script. At last, we started without him, eating at a long table set outdoors, served by Romano, the neophyte butler, who was sweating nervously. The children, whose training, if any, was imperceptible, amused themselves by making bread pellets to throw at the guests, keeping up a nonstop clamor of shrieks and patter (“I want to kill those children,” one of the guests kept hissing at me), and varied at times by Christian slipping from his chair and crawling around under the table, happily hiccuping. When Vadim finally deigned to honor us with his presence, we were at the main course.

“What are these croquettes made of?” he demanded.

“Veal,” Jane told him.

He scowled. “Why do you have veal when you know I like chicken?” he said coldly. (The rest of us pretended we hadn’t heard, but I thought, You can bet your boots the next time they’ll have chicken!)

Vadim (it is pronounced Vadeem—and no one ever calls him Roger)—is forty, ten years older than Jane. His full name is Roger Vadim Plemiannikov; he was born in Paris of a Russian refugee father and a French mother. Tall and dark, with big ears and big teeth, he has a full, curling mouth like those in ancient Assyrian bas-relief sculpture, narrow, slightly slanting eyes, and a strong nose. He says he looks like Abraham Lincoln, Fernandel, Jerry Lewis, and Christian Marquand’s sister. He and Jane talk to each other in French, which she speaks extremely well. His English is heavily accented : “Zat ees ’ow I seduce Jane. She say to me, ‘Do you know what you look like?’ and I say, ‘Abraham Leencoln’ and she say, ‘Ow did you know?’”

Whenever he speaks, Jane looks at him adoringly, mesmerized by every word. After five years, the enchantment, however inexplicable it may be to many outsiders, is still very much alive. “We lived together for two years before we got married,” Jane told me, “and we could have kept on. I don’t basically like marriage, but I think it would have been just as square to go on being an old unmarried couple. I belong to him, whether I’m married or not. Marriage is a commitment, the one step further. I think Vadim felt he needed to make that extra step.”

He scowled. “Why do you have veal when you know I like chicken?” he said coldly.

For a girl who used to tell interviewers, “Marriage is obsolete,” and who was often quoted as saying, “I have never been able to love the same man for more than a year,” Jane certainly has had a change of heart. Although there are cynics who view the romance as the classic cliché of the girl and the European ladies’ man, it is generally admitted by their friends on both sides of the Atlantic that there is no girl more determinedly and raptly committed to making a go of marriage.

In fact, she has married him not once, but twice. The first time was in August, 1965, when the couple flew in a chartered plane from Hollywood (where Jane was filming The Chase, with Marlon Brando) to Las Vegas and were married by a judge on the top floor of the Dunes Hotel. “My brother Peter brought his guitar and played and sang,” Jane told me, and we gambled all night. We didn’t have a wedding ring because I didn’t want one—it’s only a voodoo symbol and I don’t like symbols—but the judge was so upset that just for the ceremony we borrowed a ring from the best man’s wife.”

The marriage was not legal in France because Vadim forgot to register it with a French consul within the required time limit. So in May, 1967, they were remarried in a Civil ceremony by the mayor of a French village near their farmhouse, which is thirty-eight miles from Paris. After the ceremony, Jane told the French press, “Now I feel totally, legally French,” adding, somewhat unnecessarily, “I love Vadim completely.”

Nothing could be more obvious than this last statement, along with the fact that in their household it is Vadim who rules the roost. Henry Fonda’s restless, capricious daughter, who for years didn’t know what she wanted and therefore spun like a whirligig in all directions, has transformed into a woman who regards herself primarily as Vadim’s wife, with everything else secondary, including her career. Being Vadim’s wife is no sinecure. It is no post for weaklings. It requires stamina, youth, health, self-control, patience, and dedication, as I was to note during my Italian visit.

After lunch Vadim went off to the studio, leaving Jane to try to solve the problem of the missing hot water and the vanishing lights, the arrangements for departing and arriving guests, the preparations for Saint-Tropez. (As a typical European husband, he never lifts a finger to help around the house. When Jane was finishing Barefoot in the Park in Hollywood, there was a period when she had no maid. She got up every morning at six, arrived on the Paramount set by eight, worked all day, left at six or seven at night, had a ballet lesson, went home to Malibu Beach—where she had rented a cottage because that was where Vadim wanted to be—and cooked dinner, often for guests whom Vadim had invited. It was a strenuous routine for anyone, let alone an international movie star who was then getting paid $300,000 a film.)

She looked a little tired that clay in Rome. She wore no make-up except mascara on the lashes that shade her violet eyes, and a foundation lotion that gave her skin a pearly glint. A French writer, Georges Belmont, once compared her to a black panther in a zoo (“Deep in her eyes behind the bars of her cage of skin… [you] see the black panther pacing around”). She seemed to me more like some soft-eyed, furry young wild thing—a lemur or a gazelle, perhaps—easily startled, gentle, vulnerable, yet with a stubborn strength and the adaptability to survive in the jungle….

A photographer who had come to take pictures asked her to put on something different and fix her hair for the photographs. “I’ll change my clothes but I won’t fix my hair,” she said calmly. (She has a low, husky, clotted-cream voice, “a hypnotic voice,” someone has called it.) She was wearing her long, amber-colored hair in the tousled just-got-out-of-bed style first popularized by Bardot, Vadim’s tutelage. (Jane’s hair, like Bardot’s, was once brown, but Vadim prefers blondes.) All Vadim’s girls have worn their hair this way. That’s the way Vadim likes it. Ergo, that’s the way they wear it.

After changing clothes, Jane spent an hour posing for photographs in different parts of the grounds, while I waited near the house, with the children charging around me, shooting cap pistols. “Don’t they ever take naps?” I asked hopefully. The answer was No.

Dinner that night was, like lunch, delayed for several hours, as again we waited for Vadim, who had returned to the villa and was closeted in his study. Among the guests were Jean Servais, the French actor (Rififi), looking like a combination of Arthur Godfrey and Jean Gabin, and his wife, who talked baby-talk French and kept opening her eyes very wide. While we waited, Jane served drinks in the salon, a huge, rather overwhelming drawing room with red silk sofas, blue velvet chairs, antique carved and inlaid chests, a marble column adorned with fat, gilded cherubs and gilded lyres and wreaths, giant candelabra holding dozens of candles, and an enormous fireplace with carved wood figures on each side.

Jane seemed tense and exhausted, but she tried to keep the conversation going. (She is always anxious to please, afraid she’s not doing things right, afraid people won’t like her, afraid of being boring.) As it got near ten o’clock, word came from the kitchen that Romano’s wife had collapsed in tears, and Jane rushed down to the kitchen to soothe her. At last Vadim made his appearance to greet his guests, and we finally made it to the dining room. Vadim and Servais did most of the talking, while Jane sat quietly at the foot of the table, her pale skin luminous in the candlelight and her soft eyes like flowers. Suddenly I knew where, long ago, I had seen before that same type of poignant face, so tender and gallant—the young Lillian Gish of silent films like Way Down East and Broken Blossoms.

After dinner we returned to the salon. Jane put some Dionne Warwick records on the player and then curled up on the floor in front of the fire. “If you write about me at all,” Vadim said, standing with one hand on his hip and gesturing languidly with the other, “I ask only one thing: that you say I am the best in the world at lighting a fire.” Nevertheless, it was Jane who first got the fire started, although later Vadim did poke it about and add a log or two. It was late when the guests left. Jane showed me to my room, where she herself had seen that everything was in order, down to the books and magazines which she had put on the bedside table. I fell asleep listening to the incessant moaning of some insomniac pigeons outside my window. In their rooms above, Jane was finishing the packing for Saint-Tropez. (She’s never had a personal maid. “I couldn’t stand having one around all the time,” she said, “or traveling with a retinue of servants, although there are time when I think it would be heaven. But I’ll never do it. I’ll never be a ‘movie star’ actress. I couldn’t be.”)

When I awoke the next morning, the villa was peaceful. Jane and the others had risen at seven and left at eight for the airport. She couldn’t have had more than four hours’ sleep. I wondered where she got the energy to manage the dual role of housewife and movie star and how long she can keep it up.

Jane’s fierce determination to be a good wife and to make a solid, lasting marriage undoubtedly stems from her childhood background of emotional insecurity, domestic discord, and tragedy. Her mother killed herself when Jane was twelve—Jane has had three stepmothers—and it is strange how often her life has been touched by other violence: her best friend’s mother, Margaret Sullavan, committed suicide, as did her brother Peter’s best friend and Brooke Hayward’s sister, also a close friend of Jane and Peter. As for Jane, she grew up shy, frightened, desperately unsure. She’s had a lot to overcome, not least the often crippling handicap of a famous parent.

“If you write about me at all,” Vadim said, standing with one hand on his hip and gesturing languidly with the other, “I ask only one thing: that you say I am the best in the world at lighting a fire.” Nevertheless, it was Jane who first got the fire started, although later Vadim did poke it about and add a log or two.

Henry Fonda’s ancestors were Italians who emigrated from Genoa to the Netherlands. Their descendants were Dutch settlers in upper New York State, but Henry was born in Omaha, Nebraska. He was working for the telephone company and studying journalism, when he was persuaded by Marlon Brando’s mother, a neighbor, to join the local theater group in which she was active.

From there he went East, to become famous in the theater and on the screen. Early in his career, in 1931, he married the actress Margaret Sullavan. They were divorced in 1933. In 1936 he married Mrs. Frances Seymour Brokaw, the divorced wife of multimillionaire George Brokaw. Their first child, Jane, was born in New York City on December 21, 1937. The family moved to California when Jane was about five.

“We lived on a twenty-four-acre farm in Brentwood, a place called Tigertail Road. My father was crazy about early-American history, and the house was filled with cobblers’ benches and lamps made from butter churns. When my father wasn’t filming, he liked to go out and plow the fields, and he wore Levis and work clothes. His friends, John Wayne, John Ford, James Stewart, all dressed the same way. They used to come to the house and sit around playing cards and talking cowboy talk. It was all pretty fakey, but it was fun for me and my brother Peter, who’s two years younger. We had chickens, rabbits, dogs, cats, donkeys. We wore blue jeans and played cowboy, too, like the grownups. I’d sit on the roof with Peter and I’d say things like, ‘Tell me the truth, Pete, which one of us could lasso a buffalo better?’”

Jane was never close to her mother (“I didn’t understand her”), and of her father she now says: “He’s not the kind to bounce his children on his knees. He’s very shy and reserved, with all sorts of defenses. For years I’ve tried to forge my own identity and separate myself from my father…But there’s a deep-seated bond between us. I’m very much like him in many ways.”

One of these ways, the most obvious one, is her face. She grew up hating her looks. Everyone was always commenting on her resemblance to her father—they still do—and she resented this, although she once said, “All the best in me I inherited from my father.” In her bedroom she keeps a framed photograph of her parents on their wedding day. It shows the groom in a high silk hat, handsome, smiling, the face uncannily like Jane’s.

When Jane was ten, they moved back East, where her father was to appear on Broadway in Mr. Roberts. The family lived in a rented ten-room house in Greenwich, Connecticut. “It was a horrible, big, rambling house, full of termites,” Jane says, “a strange house, all very sinister.”

Brooke Hayward, who went to school with Jane in Greenwich, remembers the house, too. “I used to go there for dinner. Even when her mother was home, she never joined us. She would stay in some dark room, but Henry would eat with us. He was very tense and aloof and strange, I thought. I remember they had a Dalmatian who killed chickens, and Henry took a dead chicken and hung it on the dog’s neck with a chain and left it there until it rotted off. I suppose that’s the way you cure a dog of killing chickens, but I thought it was horrible. I was terrified of my mother and of Jane’s too, and scared to death of Henry, but Jane had spunk. She wasn’t naughty, but she used to bait him and he’d explode.”

“When you’re the children of a famous father, you face a great deal of resentment. When I was at school, I think I was resented by everyone.”

Jane is reticent about those years, but Peter talks a blue streak. Tall, thin, good-looking, he has a more kinetic personality than his sister, an IQ of 100, and a flashing brilliance that can be quite dazzling at times. He doesn’t gloss things over:

“Let’s face it. We didn’t have a ‘normal childhood.’ We were Henry Fonda’s children and we were miserable a lot of the time….We moved around a lot when we were kids, always being taken care of by other people. Then, too, when you’re the children of a famous father, you face a great deal of resentment. When I was at school, I think I was resented by everyone.”

At the end of 1949 Henry Fonda issued a statement through his agent that a divorce was being arranged. They never got around to it. The following April, Mrs. Fonda, then in a mental hospital, slit her throat with a razor blade, leaving a note that said, “Sorry. This is the best way out.” Less than a year later, Fonda married a twenty-two-year-old actress, Susan Blanchard, Oscar Hammerstein’s stepdaughter. Jane went to live with them. Previously, the children had stayed with their grandmother, Mrs. Seymour. Their mother left a net estate of $600,000, half of it divided equally between Jane and Peter, the rest in trust for them, held by her mother, Mrs. Seymour, whom she also wanted to have custody of the children. Henry Fonda contested this, and won custody of Peter.

According to Brooke, the children were not told what had happened. “I’ll never forget the day Jane found out. We were sitting in art class at school, surreptitiously reading a movie magazine, and there a story, ‘Why Henry Fonda’s Wife Cut Her Throat.’ I remember turning the page fast. Jane reached out her hand and turned the page back. It was an awful moment. She never said a word about it, not then or later. But at camp that summer she used to have terrible nightmares and she would wake up screaming for her mother.”

After boarding school at Emma Willard, Jane and Brooke both went to Vassar. Jane stuck it out for two years but hated it. “She had no direction or purpose,” Brooke says. “She wouldn’t get up mornings and she never worked.”

When she left Vassar, Jane persuaded her father to let her go to Paris to study painting. (“It was just an excuse. At that age you always think if you go far away you’ll be different.”) At first she was lonely and unhappy, but then she began to make friends and she stopped going to art school. It was during this period, when she was nineteen, that she first met Vadim.

“I went to Maxim’s one night with Christian Marquand, the actor, Vadim’s best friend. I had meet Christian through Susan, my father’s third wife. They were divorced when I was at Vassar, and he married Afdera Franchetti [a twenty-three-year-old Italian countess]. I was very fond of Susan…. Vadim came into the restaurant with Annette Stroyberg, who was twenty and very pregnant. They weren’t married yet, as he was still married to Brigitte, with whom he had recently had his first big success, directing her in And God Created Woman. I was really a typical young American girl, and they all terrified me. I had this very proper façade that I used to cover up my shyness, but underneath I was intimidated and frightened! I’d heard a lot about this wild, sinister, cynical, debauched, crazy man, and when I saw this creature arrive, with his slanted Russian eyes, I thought, Oh, God! I know now that I was attracted to him, although at the time I thought I hated him.”

After six months, her father sent for her to come home. (“He knew that I was going out with what is known as a fast crowd, and I guess it made him nervous.”) Back in New York she took a few piano lessons and gave up, studied at the Art Students League and quit, made a stab at learning French and Italian at Berlitz, worked briefly reading scripts for producer Warner Le Roy, sold subscriptions to the Paris Review. (“She was the most spectacular of our assistants,” recalls editor George Plimpton.)

She was bored and restless. She wanted something to do but didn’t know what. (“I was twenty-one and I started to panic.”) She went to Hollywood to stay with her father and Afdera in a house at Malibu. One of their neighbors was Lee Strasberg, whose wife was coaching Marilyn Monroe in Some Like It Hot. Jane became friendly with the Strasbergs’ daughter Susan, who suggested that she talk with Lee. The result was that she went to study at the Actors Studio in New York. Weeks later, Lee told her, “When I met you in Malibu there was absolutely nothing about you that would have made me think that anything was going on behind that façade—but then suddenly I saw absolute panic in your eyes, and that was what interested me.”

Jane had already appeared on the stage, but the thought that she might become an actress apparently never entered anyone’s mind. When she was sixteen, she acted with her father in a benefit performance of The Country Girl in Omaha, Nebraska. “It was a very small part,” Henry Fonda remembers, “and she couldn’t have cared less about acting. My sister suggested her, and Jane just did it for a lark. A couple of years later, we were summering at Hyannisport, and she told me she’d like to be an apprentice at the Cape Playhouse, but the only reason was because on a weekend from Vassar she’d met a young Yale man who was stage manager at the Playhouse.”

Jane’s reaction to this is to say: “I was terribly shy and I didn’t feel comfortable on the stage. I was terrified of committing myself because I was afraid I wouldn’t make it. I know now that I was desperately in love with acting, but I was afraid, so I did everything else instead. In two months with Strasberg my life changed.”

She shared a duplex apartment on East Seventy-fourth Street with Susan Stein, daughter of the head of MCA, and worked as a fashion photographer’s model to pay for her acting lessons. She worked hard and studied hard. Josh Logan, an old friend of her father’s, gave her her first screen role, opposite Tony Perkins in Tall Story. “I know he only gave me the part because of my father. I really hated it. I played a college girl in love with a baseball hero, and I looked like a chipmunk. I lost whatever self-confidence I’d recently learned. I’d see beautiful girls all over Hollywood, girls much prettier than I, and that depressed me. I was unhappy and scared. I spent a whole weekend crying in my apartment and I swore I’d never make another film in my life.”

Logan next cast her in a Broadway play, There was a Little Girl, in which she played a rape victim. The play had six performances and got terrible reviews in which it was called “gamey,” “tasteless,” “meretricious.” These were raves compared with what greeted her appearance in The Fun Couple (John Chapman called it “godawful”), which lasted only three performances. It was a traumatic experience, and for a week Jane cried. The play was directed by a young Greek, Andreas Voutsinas, whom she had met at the Actors Studio and with whom she thought she was in love. She was to leave him for Vadim.

She got up every morning at six, arrived on the Paramount set by eight, worked all day, left at six or seven at night, had a ballet lesson, went home to Malibu Beach—where she had rented a cottage because that was where Vadim wanted to be—and cooked dinner, often for guests whom Vadim had invited. It was a strenuous routine for anyone, let alone an international movie star who was then getting paid $300,000 a film.

She had gone back to Hollywood to make some more films, among them A Walk on the Wild Side, in which she moved across the screen with an entrancing wiggle waggle, playing a young prostitute in a New Orleans brothel with such verve that she charmed the critics, and The Chapman Report, which won her the “worst actress of the year” award from the Harvard Lampoon. Vadim came to Hollywood to discuss a deal with Paramount. “He telephoned me, and we met in the coffee shop of the Beverly Hills Hotel. We had nothing to say to each other. He wanted me to play a part in La Ronde, but I had my agent send a wire saying that under no circumstances would I make a movie with Roger Vadim.”

In 1963 she went to Paris to play opposite Alain Delon in The Love Cage for René Clement. She suddenly found herself, at twenty-five, the toast of the town. She had no press agent, but French photographers and reporters besieged her apartment. For two weeks she gave interviews from morning till midnight, saying things like “I only play love scenes when I’m in love with my film partner” and “Give me enough red wine and I’ll go on and on….” The French press was delighted. Paris Match gave her a cover and ten pages; Candide, the political weekly, said of her, “When she walks, one hears music”; even the recondite Les Cahiers du Cinéma put her on the cover and devoted eight pages to an article which deliriously called her “one of the most beautiful girls on earth.”

If Paris fell in love with her, it was eagerly reciprocated. She rented a furnished apartment in a fifteenth-century house in the Latin Quarter, started buying her clothes at Balenciaga and Givenchy, and went to all the fashionable tout Paris parties. “Like a young wild thing,” commented René Clair, “she’s galloping too fast, bursting into flame too easily.”

It was in this mood that she met Vadim again. “I decided to find out what was behind this obsession of mine about him. When a woman is that aggressive about a man, there’s something behind it. He knew this, too. I found out he was all the way down the line totally the opposite of what I’d thought he was. We started seeing each other.”

Jane was in love, so much so that she turned down the role of Lara in Doctor Zhivago because she couldn’t bear to spend nine months in Spain on location, away from Vadim. Instead, Vadim directed her in La Ronde, in which she spent most of her scenes in bed (she calls it “the most restful picture I ever made”); and he took her to his old stamping grounds at Saint-Tropez, where they walked barefoot on the beach and ate caviar and drank vodka at candlelit dinners in Chez Feliz his favorite place, just as he had done with her predecessors.

According to his detractors, by no means a minority group, Vadim was an unsuccessful actor, novelist, and journalist before he had the luck to hit the jackpot when he ran across Bardot on a French movie set where he was doing various off-camera chores. According to his own version, however, he was a brilliant actor and a successful writer: “I have always been a writer: I’ve written a novel and I had already done one or two successful comedy scripts when I met Brigitte. I spent two years as a journalist on Paris Match because her father felt I should have a regular job.”

Bardot was fifteen when he met her, and he forthwith moved into the house of her well-to-do middle-class parents. She was eighteen when he married her. He took her photographs around to agents and set up press conferences with his wife in bed, covered only by a sheet. He hustled nine movie roles for her before directing her in And God Created Woman, which turned out to be manna indeed for both of them.

Who is to judge why any woman falls in love? Who is to gauge what she gets out of it?

However, she fell in love with the actor who played opposite her in the film; but before she divorced Vadim in 1957, he directed her in another movie. By then he had taken up with a young Danish girl, Annette Stroyberg, who used to hang around the set waiting for him. She and Vadim and Bardot would all eat together every evening, a happy trio. The day after the divorce was granted was Annette’s twenty-first birthday, and she celebrated by giving birth to Vadim’s daughter, Nathalie. Bardot offered to be the baby’s godmother but was politely turned clown. Six months later, Annette and Vadim were married. Alas, this idyll, too, was doomed to end. The French press hinted that Annette was having an affair with Sasha Distel, a guitarist and singer (and ex-boyfriend of Bardot, as was also Christian Marquand, who used to escort Jane and was later best man at her wedding to Vadim: the personal relationships surrounding Vadim are nothing If not intramural). Shortly before Vadim’s divorce from Annette, he directed her in Les Liaisons Dangereuses, a film which so shocked the French that for some time it was banned for export. (Naturally, it contained a love scene with Annette almost naked.) To the New York premiere in 1961 he brought eighteen-year-old Catherine Deneuve, who subsequently left him—after bearing his son—for still another Bardot ex-boyfriend, Sami Frey.

Vadim has been called a Pygmalion, a Svengali, because of his record for plucking nubile maidens from obscurity, changing their appearance and their personalities, taking their clothes off, and directing them in movies with variable degrees of success. Jane is in a different category from any of the others. She is Henry Fonda’s daughter, independently wealthy, and an established actress before she took up with Vadim. She is also older than the others were when they succumbed to Vadim’s charms, and she is more intelligent, presumably enough so to know what she wants and what she is doing. Besides, who is to judge why any woman falls in love? Who is to gauge what she gets out of it? “With Vadim,” Jane says, “I come closer to myself, to knowing who I am. I trust him. He has the ability to make a woman bloom. He gives her confidence in herself.”

These are statements with which Vadim is in complete agreement, and is not at all bashful about saying so. “I certainly do help women to live,” he told me when I saw him in Hollywood, “because I help them to be happy. I make women bud and bloom. I am like the gardener who waters a plant and it blooms.” There wasn’t much I could say to that. It reminded me of the time, not long after their marriage, when Jane and Vadim were interviewed on a London television show, and Jane proudly announced, “Vadim has made me a woman,” a statement to which no one else on the program could think of a suitable rejoinder, although one of the more cutting remarks made privately was, “He may have made her a woman, but can he make her an actress?”

This was an unkind reference to the dismal quality of so many of her films (“She has survived some of the worst pictures of any young actress,” Henry Fonda said to me), the mediocrity of which she is the first to admit, with the honesty and humility—and the courage—that are her outstanding characteristics. There isn’t anything she has done with which she is satisfied, although La Curée, released in America as The Game Is Over, came closest, probably because Vadim directed. A pretentious version of the Phaedra legend, its nude scenes showed the lovers trysting in pool and garden, the sexual act symbolized by flashes of writhing green lights which unfortunately gave me the impression of watching two cucumbers copulating. The film was shown at the Venice Film Festival, where it was received without enthusiasm and was later seized by Italian authorities on an obscenity charge. It opened in New York to pulverizing reviews, but the French loved it and it had a successful Paris run.

As far as Jane’s ability is concerned, the potential is there. Arthur Penn, who directed her with Brando in The Chase, likes and admires her: “She’s a damn good actress, if she’d get away from pat, commercial comedies.” Mike Nichols has said he would like to direct her, although he told me that he can’t tell if it’s “because of admiration for her acting or the way she makes me feel. She’s so wonderful as a girl! You see a girl like that with a beautiful face and a marvelous body and you think, If I could only talk to her, and with Jane you can, because she’s so bright…. I saw her in The Chase, and she’s quite extraordinary in some scenes.”

It was Otto Preminger who got one of the best performances out of her in Hurry Sundown, an astonishing mishmash of a movie. “She has great understanding of character,” he said to me. “She could give up all the comedy parts and be a serious actress. She’s good at comedy, but underneath there’s a sense of tragic feeling. She can be very moving.”

She is symbolic in that she is a member of a new international species, that is, the interchangeable youth of today, at home all over the world, despising cant and the discredited hypocrisy of their elders

After Barbarella, Jane and Vadim went to Brittany, where he directed her in an Edgar Allan Poe story, Metzengerstein (a title almost certainly due for change), one of a trio of Poe stories: the other two are directed by Louis Malle (starring Bardot) and Fellini.

After that, Jane hopes to take time off to have a baby. (Someone once said of Vadim: “He’s an absolute publicity genius. Every time a new film of his is released he is either about to marry the star or divorce her or father her child.”) She would like to spend at least half the year on the farm she bought in 1964 near Paris. When she bought it, it was a nineteenth-century barn, with cows living in what is now the dining room and hay piled in the bedrooms. “We had no furniture, no heat, no electricity. We slept in sleeping bags on the floor and ate on a board propped on sawhorses.” She was her own architect, and she taught workmen how to build a stone wall without cement. She found a medieval town fifty kilometers from there that was going modern and putting in sidewalks, so she bought their cobblestones, several tons of them, and had them put in her courtyard, with grass planted between them. She had birch and oak trees planted. She put fireplaces in every room; and she designed the bathroom, separated from her bedroom by a wall of glass “because Vadim likes to lie in bed and watch me in the bathroom.”

She has put her heart into this place. “I’m preparing it for Vadim,” she said, “and for Vadim’s children and his children’s children. There comes a moment in your life when you want to put down roots. You want a real home. You want to know with whom you’ll be in a year, in ten years.”

This is a strangely old-fashioned nesting instinct for such a modern girl. Yet there are aspects of her intense absorption with love that are symptomatic of today’s generation. As the daughter of Henry Fonda, with her family background, and as a highly paid box-office draw and a transatlantic film star, she is not, of course, typical of American youth. However, she is symbolic in that she is a member of a new international species, that is, the interchangeable youth of today, at home all over the world, despising cant and the discredited hypocrisy of their elders, reflecting traditional patterns (or, rather, reweaving them in new designs), and, above all, touting salvation through love, a credo that is as new and immediate as it is ancient. She has a touching faith, or perhaps it is more of an urgent hope, in the magic of love. The nice thing is that for her it seems to be working.

This story is collected in Latins Are Still Lousy Lovers.

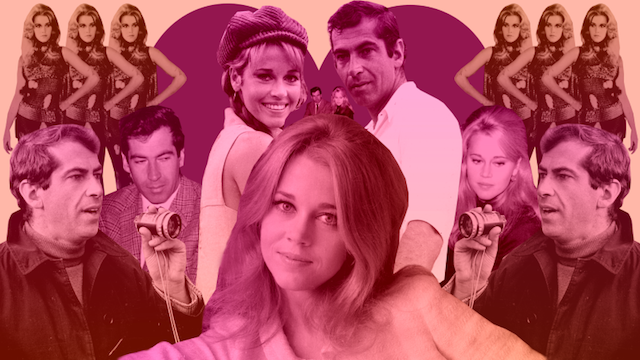

[Photo Credit: Elena Scotti]