To artists and intellectuals, the twentieth century has posed no questions more vexing than these: First, can art make sense of the Holocaust? And second, why do the French love Jerry Lewis?

The first question can’t really be answered, at least not in the space allotted here. As for the second, it’s my own opinion that the French have confused sloppy, uneven filmmaking with Godardian antiformalism. Regardless, raising these two issues on the same page is not just a pointless exercise in non sequitur. Because Jerry Lewis, like Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi before him—not to mention the producers of the NBC miniseries Holocaust—has transformed the incomprehensible into art.

He did this two decades ago, in 1972, a year of cultural ferment that also saw a black man, Sammy Davis Jr., snuggle Richard Nixon on national television. It was Lewis’s 41st film (but his first to deal with the mass destruction of European Jewry), and it turned out to be the most notorious cinematic miscue in history—unfinished, unreleased, said by the few who’ve seen it to be almost unwatchable. Oh, there are also Von Stroheim’s Queen Kelly and Welles’s Don Quixote, among other busts. But no other film, seen or unseen, can boast both Nazi death camps and the auteur responsible for The Nutty Professor.

There is only one The Day the Clown Cried.

Were it ever released, the film would surely provoke as great a stir as a rediscovered Balanchine ballet or an unearthed Van Gogh—if not on the pages of the Arts & Leisure section, then at least among scores of sitcom writers, apprentice film editors, clerks in comic-book stores and others who are expected to wear high-top sneakers to work and whose fascination with Jerry Lewis transcends easy irony. But so far The Day the Clown Cried hasn’t surfaced, and it likely never will. Only a handful of people have ever seen it. And as they grow older ….

To preserve their memories for future generations, Spy has tracked down and recorded the impressions of eight people who have seen The Day the Clown Cried or who participated in its creation. You and I may never watch in mute wonderment as the lost gem lights up the screen before us, but now, at least, we can know what it felt like for those who were there. But first, the back story.

It sounds like a punch line in an overheated Hollywood satire: Jerry Lewis in Auschwitz. Depending on your taste, the prospect may be as offensive or as intriguing as … well, truly, no metaphor measures up to the particulars. A synopsis:

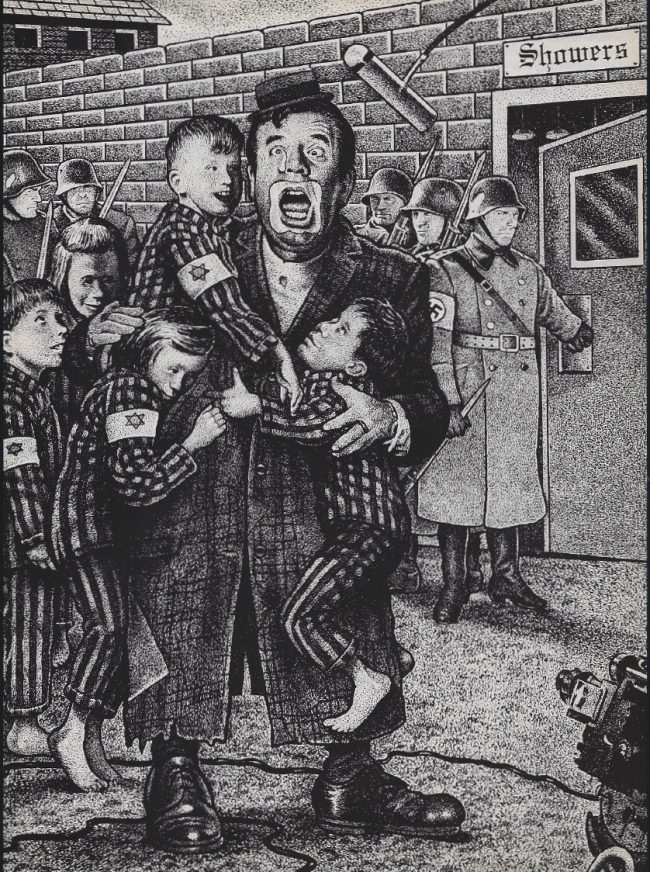

An unhappy German circus clown is sent to a concentration camp and forced to become a sort of genocidal Pied Piper, entertaining Jewish children as he leads them to the gas chambers. The story is meant to be played as drama. By all accounts, no one sings “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” and Tony Orlando does not appear.

The Day the Clown Cried was to be Lewis’s first serious film as both director and star, a proto-Interiors, “a turning point in the career of one of the most unusual performers in history,” as the movie’s press kit put it, adding that Lewis is “a 20th Century … phenomenon like atomic energy, moon shot, heart transplants and hippies ….” Nevertheless, many in Hollywood were skeptical about the project. Many outside Hollywood were skeptical, too. Even French film critics were skeptical. As Jean-Pierre Coursodon would write a few years later in Film Comment, “While it is not surprising that Lewis should come round to disclose a fondness for pathos shared by so many comedians (there had been warning hints in his earlier pictures), his selection of such a painfully bizarre theme does come as a bit of a shock.”

Lewis himself was skeptical when he first read the script, though not about the material itself. Moved, he found the screenplay to be a devastating indictment of the Nazi atrocities, not to mention the midcentury leader he has called “the beady-eyed lunatic with the comic mustache who had started it all.” Lewis’s concern was whether The Day the Clown Cried was a proper Jerry Lewis vehicle. In Jerry Lewis in Person, his 1982 autobiography, he recounts his reaction to the producer, Nathan Wachsberger, who asked him to play the part in 1971:

“Why don’t you try getting Sir Laurence Olivier? I mean, he doesn’t find it too difficult to choke to death playing Hamlet. My bag is comedy, Mr. Wachsberger, and you’re asking me if I’m prepared to deliver helpless kids into a gas chamber. Ho-ho. Some laugh—how do I pull it off?”

He shrugged and sat back.

After a long moment of silence I picked up the script.

“What a horror … It must be told.” [Ellipsis Lewis’s.]

The script had actually been written ten years earlier by Joan O’Brien and Charles Denton (she was a former PR woman who created the John Forsythe TV series To Rome With Love; he was a TV critic for the Los Angeles Examiner). Like a lot of screenplays, The Day the Clown Cried was optioned by a string of producers; unlike a lot of screenplays, it attracted the attention of Milton Berle, Dick Van Dyke and Bobby Darin—any one of whom would have no doubt been as capable as Jerry Lewis of playing the title role with finesse and taste. But it was Lewis, finally, around whom the requisite financing coalesced, and he took his responsibility to heart: “I thought The Day the Clown Cried would be a way to show we don’t have to tremble and give up in the darkness,” he wrote. “[The clown] would teach us this lesson.”

Lewis plunged into preproduction with the rigor of a Streep or a De Niro, touring Dachau and Auschwitz and losing 35 pounds on a grapefruit diet. He rewrote the script, changing the protagonist’s name from Karl Schmidt to the more distinctive—and more Jerry-Lewis-movie-like—Helmut Doork. With Wachsberger providing the financing (his other efforts include They Came to Rob Las Vegas), and with Lewis as both star and director, The Day the Clown Cried began shooting in 1972 in Paris, moving on to Stockholm, where most of the film was shot. Lewis’s costars included the Swedish actress Harriet Andersson, who had been directed by Ingmar Bergman in Smiles of a Summer Night; the German actor Anton Diffring, who specialized in playing very bad Nazis; and a bunch of unwitting Swedish children. “An International Cast!” the ads might have trumpeted.

It’s not easy to get specific details about what happened on a film set 20 years ago in Sweden when the producer is dead and the director-star refuses to be interviewed. Nevertheless, it seems safe to say that something went terribly wrong on the set of The Day the Clown Cried. By Lewis’s account, Wachsberger took off to the south of France before the first day of shooting, the promised financing dried up shortly thereafter, and Lewis began spending his own money. Before the shoot had wrapped, he told Variety that he had temporarily shut down the production. He also denounced Wachsberger, who promptly filed suit, claiming breach of contract.

These contretemps alone would have been enough to doom the project, and screenwriters O’Brien and Denton were distressed to read about them in the trades, though they were even more distressed that neither Lewis nor Wachsberger owned the legal right to be shooting their script in the first place: According to the screenwriters, Wachsberger’s option had run out before filming began. “Jerry knew the option had expired,” says O’Brien today. “But he decided to go ahead with it.”

Lewis endured, sinking his own wealth (not easily renewable at that point in his career) into the filming of a property he didn’t own, on the assumption that audiences who had loved him imitating retards would now want to see him escorting children to their death. To make matters even more Coppola-esque, Lewis’s health was bad, and he had, he would later admit, a debilitating addiction to Percodan. “I think sometimes it’s difficult to be a director and [the star],” says Harriet Andersson, who is somewhat philosophical about her Day the Clown Cried experience. Sven Lindberg, a Swedish actor who played a Nazi, remembers Lewis as “nervous” and preoccupied by his money troubles: “It was clear he was not in good order those months here in Sweden.”

“I almost had a heart attack,” Lewis told The New York Times shortly after finishing the shoot. “Maybe I’d have survived. Just. But if that picture had been left incomplete, it would have very nearly killed me …. The suffering, the hell I went through with Wachsberger had one advantage. I put all the pain on the screen.” Whether or not you believe that the pain incurred in dealing with an undercapitalized motion picture producer is translatable into the pain incurred at Auschwitz, you have to admire Lewis’s dedication (to use a nonclinical term) and rue the fact that no documentary film crew was on hand to capture The Making of “The Day the Clown Cried.”

“I was terrified of directing the last scene,” Lewis told the Times. “I had been 113 days on the picture, with only three hours of sleep a night—I was exhausted, beaten. When I thought of doing that scene, I was paralyzed …. I stood there in my clown’s costume, with the cameras ready. Suddenly the children were all around me, unasked, undirected, and they clung to my arms and legs, they looked up at me so trustingly. I felt love pouring out of me. I thought, ‘This is what my whole life has been leading to.’ I thought what the clown thought. I forgot about trying to direct. I had the cameras turn and I began to walk, with the children clinging to me, singing, into the gas ovens. And the door closed behind us.”

It must be told. Alas, it will almost surely never be seen. The Day the Clown Cried is probably lost forever. It has been left unfinished, never having made it beyond a rough cut. The production’s irregularities left the question of rights in a snarl: Claiming that it is owed more than $600,000, the studio in Stockholm has held on to the negative; the screenwriters own the copyright. Over the years, investors—Europeans, bien sûr—have tried to put together a deal to finish and release the movie. O’Brien says she and Denton won’t allow it. And there the matter rests.

But what about the work?

Lewis has a copy of the rough cut on videotape. He reportedly keeps it in his office, protected from harm and unclassiness by a Louis Vuitton briefcase. Over the years, he has screened it—or pieces of it—for a number of colleagues and at least one journalist. Attempting to piece together the lost work, Spy interviewed eight of these lucky people. Their impressions have been edited together to create a kind of roundtable discussion.

So dim the lights and sit back with a bowl of popcorn. As critic Jean-Pierre Coursodon—French critic Jean-Pierre Coursodon—points out, “Although the odds against it are staggering, it might turn out to be sublime.”

THE “PANELISTS”:

Harriet Andersson is considered a national treasure in Sweden. She refers to her director on The Day the Clown Cried as “Yerry” Lewis.

Charles Denton and Joan O’Brien, the screenwriters, were shown selected scenes by Lewis shortly after shooting was completed in 1972.

Lynn Hirschberg interviewed Lewis for Rolling Stone in 1982. He showed her the movie’s climactic scenes.

Sven Lindberg claims that his many Swedish films are unknown to American audiences. He pronounces his j’s in the Anglophone manner.

Joshua White, a television director, directed The Jerry Lewis Labor Day Telethon in 1979. At the time, he had an opportunity to screen the entire Clown rough cut. He watched it with Harry Shearer, actor, writer, Spy contributor and Telethon connoisseur,

Jim Wright is a producer who used to be on Lewis’s staff. Although Wright first brought the script to Lewis’s attention in the mid-1960s and has since had an option on it himself, he was not involved in Lewis’s production. Despite his reservations about Lewis’s version, he says that it he could get financing with Lewis as a principal, he would happily recast him: That man is very talented. He can do anything.”

SPY: What was it like seeing The Day the Clown Cried?

Joan O’Brien: It was a disaster. Just talking about it makes me very emotional [Her voice trails off].

Harry Shearer: With most of these kinds of things, you find that the anticipation, or the concept, is better than the thing itself. But seeing this film was really awe-inspiring, in that you are rarely in the presence of a perfect object. This was a perfect object. This movie is so drastically wrong, its pathos and its comedy are so wildly misplaced, that you could not, in your fantasy of what it might be like, improve on what it really is. Oh, my God!—that’s all you can say.

Can you compare it with anything else Lewis has done?

Shearer: The only thing in Jerry’s oeuvre that really is like it is a wonderful thing that he did early on in the telethon. It was a dramatic tape of an L.A. actor who hosted the Popeye show, and Jerry shot it. The guy plays Muscular Dystrophy. Its a staged reading: [scary voice] “I am Muscular Dystrophy, and I hate people, especially children, I love to make their limbs shrivel up!” They showed this for several years before cooler heads prevailed. In its sense of misplaced dramaturgy it was the closest I ever came to seeing anything that would be a real precursor to the clown movie.

Ms. O’Brien, what was the genesis of the screenplay?

O’Brien: After the war was over, when I heard what had happened in Germany, I was so ridden with guilt. And when I heard that children were put in these things, it just practically blew my mind. And then years go by, and I’m doing PR for Emmett Kelly, and Emmett said to me, “A clown doesn’t play to the adults. The only audience that matters to him is children.” I put these two things together.

Clowns and concentration camps. Can you give a synopsis?

Jim Wright: Helmut is a clown who’s really a bastard.

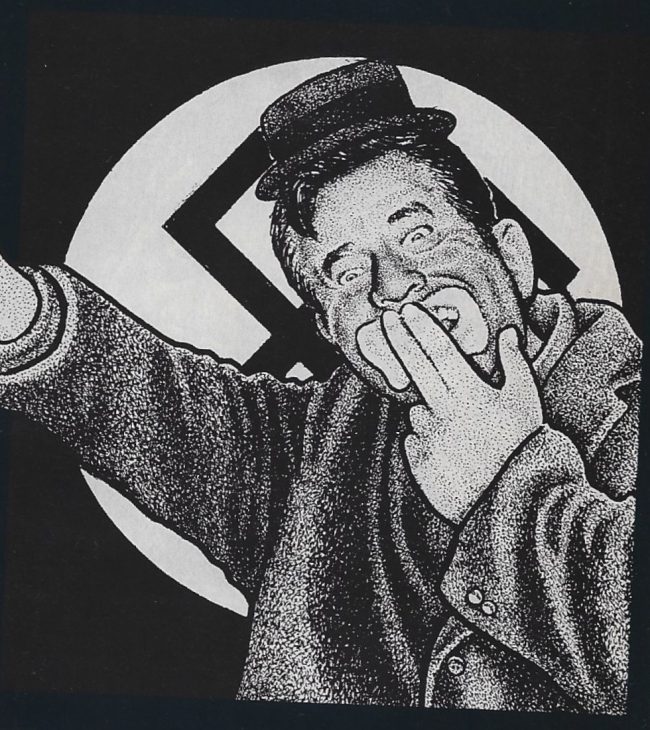

O’Brien: He uses people. He gets his girlfriend to talk to the owners of the circus he works at to try and make him the first clown. Of course, they can’t, because he’s terrible. So he gets mad, and he goes out and gets drunk, and he does these imitations of Hitler.

Wright: He talks about how nobody likes to laugh anymore because of all this Heil Hitler stuff. And he’s so drunk when he’s made a salute that he just falls flat on the floor, and we pan back and see these shiny boots right at his head. And we pull back, and we’re in an interrogating office.

O’Brien: He tells on everybody he ever knew, whether he ever felt they were anti-Hitler or not. He’s just trying to save his own skin. And even in prison he’s a nothing.

Wright: He’s put in political prison. They put barbed wire between the Jewish prisoners and the political prisoners [Helmut is not Jewish]. And all this time, he’s always bragging about what a great clown he was.

O’Brien: [The political prisoners] keep saying, “Do a routine …. Give us something to laugh at.” Of course, he can’t, because he knows they won’t laugh at him.

Wright: So they give him a big push, and he falls into the mud. He’s pounding on the ground, saying, “I am a clown, I am a clown!” And we hear laughter, and behind the barbed wire is this little Jewish girl and her brother.

O’Brien: They thought the slip was runny. Helmut doesn’t know whether they’re laughing at him or with him. So he picks up a little mud and puts it on his nose. Then they really start to laugh. More children come to the fence. Helmut gets up and says to the other inmates, “Look—they’re laughing at me! I am a great clown!”

It’s a moment of exaltation, sort of like when the ape throws the bone in the air in 2001?

O’Brien: From then on, he just thinks about the kids.

Wright: He uses soot from the stove to give him a little bit of makeup, and some pigeon droppings for the white. He trades his food for a big man’s shoes and coat, and he starts really performing for these kids.

O’Brien: The commandant lets him for a while but then says, “This has got to stop.” One day Helmut goes out and there are no children. They’ve been loaded on a boxcar to be taken to Auschwitz. But townspeople near the boxcar are starting to say, “Why are there children in there?” So the commandant puts Helmut on the boxcar to keep the kids quiet. But through a little mishap, the car pulls away, and Helmut’s on it.

So he ends up at Auschwitz.

Wright: They’re going to use him as a Judas goat to take the kids to the gas chamber and keep them from being frightened. Of course, the children don’t know it’s a gas chamber—they think it’s the showers.

O’Brien: This is not a great hero. He stands at the door and lets the children go in. But there’s one little girl who hesitates and holds her hand out to Helmut. He is shaken. And then he looks at all those little faces looking up, waiting for him to do something funny. And so he pulls a stale piece of bread from his pocket and starts throwing it in the air and trying to catch it in his mouth—fairly stupid stuff. And that’s the end.

Wright: Even at the end, you don’t know whether he did it for the kids or he did it for his own ego.

So that’s the original screenplay. Lewis altered it, right?

Wright: Jerry completely changed the clown. Instead of being an egotistical clown, Jerry more or less is like an Emmett Kelly, a very sad clown. You feel sorry for him.

Joshua White: It’s the clown as the one really miserable person. It’s Jerry’s idea of pathos—it’s not particularly original, but he really thinks in those simplistic terms.

Ms. Andersson, do you remember any of your scenes?

Harriet Andersson: We were in a kitchen or something. I’m sorry, it’s just a little confusing because I felt there … It was something wrong with it, in a way. And it was such a long time ago.

What is Helmut’s actual clowning like?

Lynn Hirschberg: Tripping, pratfalls, typical Jerry stuff. That grotesque spastic stuff that he does.

White: He does these bad silent routines and they’re intercut with these shots of blond, blue-eyed, obviously Scandinavian kids laughing in bleachers.

How did Jerry deal with the more dramatic demands?

White: The scenes were so dramatic—it was, after all, set in a concentration camp—that they were beyond his range. Other comedians who have a similar problem handle themselves better; they position themselves so that other actors take the focus in a dramatic scene. But Jerry would point the camera on himself and then attempt to be in this deep dramatic moment in which the Holocaust was playing out right in front of him.

Any specific memories—eye-rolling, teeth-gnashing?

White: I just remember rage. He played this rage because that’s what he was filled with then. He never really commits to the character. He’s always just Jerry. He’s supposed to be this schlump, but he’s got this slicked-back hair. He’s practically wearing the pinkie ring.

He literally has slicked-back hair?

White: Yes.

Charles Denton: In one scene Jerry is lying in his bunk wearing a pair of brand-new shoes after theoretically having been in a concentration camp for four or five years. I think he also has a shot of the prisoners where all the women were in Sunday outfits.

The mise-en-scène was problematic?

White: It was filmed under very difficult conditions, and it shows. It almost looks like a student film. It’s supposed to be Auschwitz, and it’s completely underpopulated. There are all kinds of art-direction conceits, like, “We’ll just play it against black, and it will look like he’s in the middle of the ring.” It’s hopeless.

Can you see the influence of any European directors?

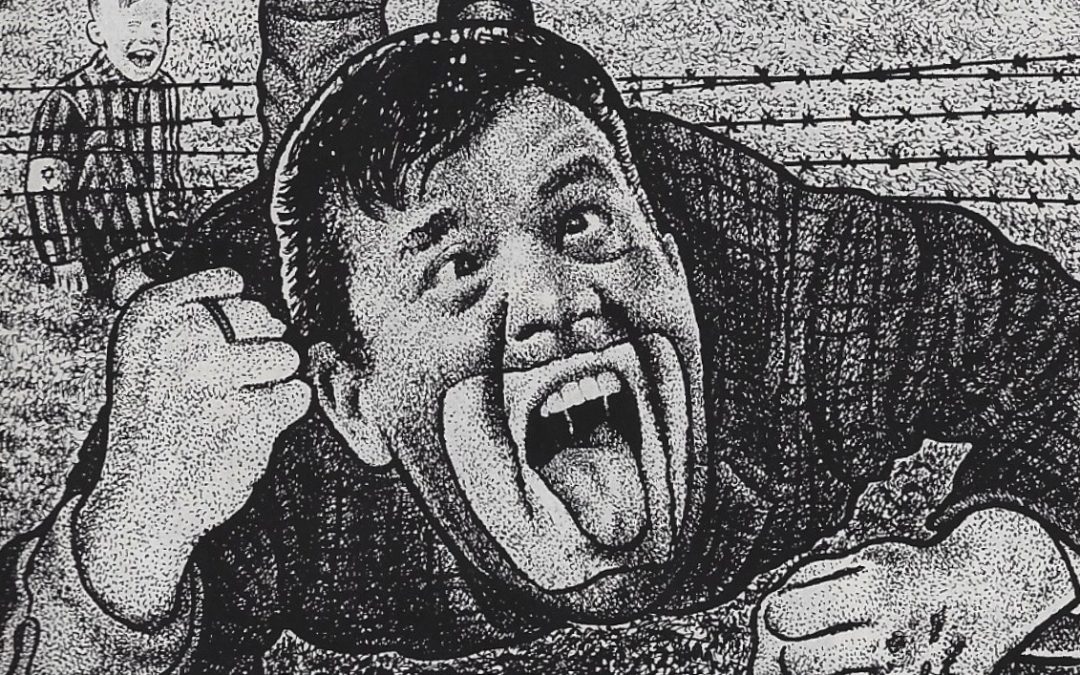

Shearer: The only European influence I can see is that of Paris street mimes. It really is that level of [turns head sideways and makes contorted, maudlin clown face].

Ms. Andersson, you’ve worked with Bergman and Jerry Lewis. Any similarities?

Andersson: I never compare my directors. I don’t think that’s fair.

Sven Lindberg: All directors direct. They are the same. But this one, Jerry Lewis, was more pressed in some ways. I was never troubled with the work—I thought it was good—but he was so nervous always.

How are the Nazis portrayed in the film?

Shearer: They’re evil incarnate. There’s no shading.

White: Anton Diffring, this hammy German actor, plays the main Nazi. You can tell he was embarrassed. The performance was right out of Hogan’s Heroes.

How does Jerry play the final scene?

Hirschberg: It’s very Pied Piper-ish. There are like 10, 15 children. They’re like seven or eight years old. Helmut rounds them up. They’re in a yard. He takes them off to the showers-slash-ovens: “Where are we going, Helmut? Where are we going?” He’s telling jokes and stories to the kids and singing songs. He does a lot of Jerry shtick—you’re supposed to laugh at his routines yet be appalled by the horror. The children are cheerful because he’s Helmut the Great. Meanwhile, of course, he’s terribly sad. Because he has a sad thing to do. But he’s smiling behind his tears, because he’s trying to embrace the children. They’re tugging at his clothes. Now he’s standing in front of the oven. The children just march in a door. It hasn’t been turned on yet. You can still hear them laughing inside. And then he sort of stands there and looks in and stands there on the outside and starts to cry. One tear rolls down the clown makeup—they make an art-direction point of it. And then he goes in himself ….

Can you describe your sensations as you watched this?

Hirschberg: I was appalled. I couldn’t understand it. It’s beyond normal computation. You look at it and think, What must he have been thinking when he did it, thought about doing it, thought it was good?

Shearer: I think Jerry probably thought, The Academy can’t ignore this.

White: It’s an idea that defeated itself. For the movie to have a center, for it to work, you had to feel for this clown. And he’s not funny, and he’s not articulate, and he’s not nice. And then the fact that this character is placed anywhere near a concentration camp where children are being killed …. He’s trying to create a tragic character, and instead he creates a pathetic character.

Shearer: The closest I can come to describing the effect is if you flew down to Tijuana and suddenly saw a painting on black velvet of Auschwitz. You’d just think, My God, wait a minute! It’s not funny, and it’s not good, and somebody’s trying so hard in the wrong way to convey this strongly held feeling.

Lindberg: My impression was that it was very serious for him to do this, because he’s a Jew. He thought this film would explain something about the horror of the Jews.

Hirschberg: He’s very proud of it. He asked, “What do you think?” Usually I would lie and say it was great. But I said, “I just don’t get it.” And he got really cold.

White: When I saw it, I felt for him, because I could see him trying to clear the hypocrisy out of his life. He was always surrounded by sycophants, but he’d just gotten off Percodan, and he was very proud of that. Then to see this film that was so important to him and that was almost incompetent was just sad. He felt the world had conspired against him to prevent him from completing it. He endowed it with great sadness. It was “the lost film.” But it is so awful—you can’t even laugh at it. It’s so hopeless, you just don’t feel anything good for Jerry.

Wright: I know Jerry could do a tremendous job with it if he’d do the script the way it was written, and I think he would now. I think he’d do anything to do it again.

Lindberg: I feel sorrow for Jerry that everything was spoiled. We were so sad, we Swedish actors, when we heard that this film would not be shown. We did our best.

“One way or another, I’ll get it done,” Jerry Lewis vows in his autobiography. “The picture must be seen, and if by no one else, at least by every kid in the world who’s only heard there was such a thing as the Holocaust.” Last year a group of producers, including Jim Wright, announced they had struck a deal to coproduce a whole new version of The Day the Clown Cried with a studio in what was then the Soviet Union. There have been … complications. But the producers continue to hope that the film will get made, in one country or another. “It’s a subject matter that has to be done,” says Wright, echoing Lewis’s concern that without The Day the Clown Cried, future generations may not be properly aware of the Holocaust. The script is said to be in the hands of Robin Williams.

[Illustrations by Drew Friedman]