A hundred or so surprisingly subdued leather boys and their women are guzzling Budweiser and Bud Lights on a bottlenecked New Jersey Transit bus to the sold-out, 21,000-seat Brendan Byrne Arena in the Meadowlands, headed to the sixth show of Andrew Dice Clay’s Fall 1989 Tour. Twenty-six rows deep, everyone is coupled up. A rough census of diamonds, ring fingers, and averted glances shows the majority are wed or engaged, with no one manifestly overjoyed to be so. From the occasional sibilant snippet around me, in fact, I get the feeling this entire busload is “completely fucking disgusted—from working all week, with their lovers, or both. I look at my calendar watch—there are only twelve days left of the 1980’s—and think about how old I’m getting: Ten years ago, these people would have been loud, stoned, ‘Luded, or tripping, headed out to see Queen or a Zappa Halloween Show, and traveling in the prurient “co-institutional” packs of a Catholic high school game bus-guys on one side, girls on the other.

Through the bus’ green plastic window, I look down at the same scene inside the four-mile line of cars stalled under the bright lights of Route 6: A stony-faced man stiff-armed at the wheel, as though he’s going 80 mph, a woman with Big Hair facing forward in the passenger seat. It’s a bizarre sight, and one I imagine will recur in the 13 states visited by the Dice show: An hour-long vituperation on women, dwarves, dogs, Latins, Pakistanis, Arabs, beggars, paraplegics, Oriental business acumen, and deejay Howard Stern, with whom Dice had some words over complimentary tickets. Born Andrew Clay Silverstein, Dice doesn’t tell Jewish jokes.

In fact, Dice doesn’t really tell jokes at all. He lacks the media range of a Morton Downey or the metalhead mass appeal of Axl Rose, but he has exactly their audience, plus the tailwind of the late-1980s fervor for “comedy” behind him and the demagogue’s genius for the lowest common denominator. In the last year, his shows have moved from the club circuit to hockey arenas, stadiums, and concert halls of 12,000 to 21,000 seats. Last month, in less than two hours, he sold out the bulk of just under 200,000 seats across the East Coast and Midwest. This is a feat no “comedian,” Eddie Murphy and Richard Pryor included, could ever approach—for reasons that become apparent as the night drags on. I haven’t seen a black or Latin face since the bus left. But for a 60-year-old Marielito manning the elevator to the Byrne Arena’s VIP lounge and a heavily booed lead-off act, Ed Griffin (introduced as “the talented young black comedian Dice personally discovered at the Comedy Store”), I won’t see another till I get back to Port Authority. I can’t escape the feeling I’ve landed in the middle of some Erskine Caldwell story about a leisurely Saturday afternoon lynching.

“Dice’s got the Brooklyn attitude to a T. He’s a real Flatbush tough … even if he’s really Jewish, out of Sheepshead Bay. Doesn’t matter.”

In this year’s push to have not just “a cult following … I’m going to have everybody” (i.e., a big Hollywood/TV career), Dice Clay has stripped his Bensonhurst-style racist-homophobic-classist act down to 90 percent sexual/misogynist remarks, which has simply proved his safest material: “I give ’em what they want. Pull their hair, rap ’em in the head a few times, say all the little things they want to hear, like ‘Fuck, pig, howl, skank.’” Other than a rehash of a few Richard Pryor jokes about black men’s penises and testicles (which wave fearfully out of Dice Clay’s mouth, like a white flag) and a diatribe on the boredom of Geraldo Rivera’s show (beginning with a fierce scream of “Spic! You keep me up to 3 a.m. to watch this shit!?”), Dice’s remnant slurs are aimed largely at what Pryor once called “the new niggers”—Asians, Arabs, and Indians. Delivered with his pseudo-Guido malaprops and monotone, they bring an atypical vitriol to his voice and body language: “What are these people anyway? They’re kind of like urine-colored. his rage over the limited English of recent immigrants has given rise to what has become his theme joke, repeated, in fake Italian-American accent, by his entire audience: “If you don’t know the language, leave the fuckin’ country!”

“Dice’s got the Brooklyn attitude to a T,” a sweet-faced kid from Park Slope named Paul explains to me, opening his third 16-ounce Budweiser since Port Authority. “He’s a real Flatbush tough … even if he’s really Jewish, out of Sheepshead Bay. Doesn’t matter. It’s a sort of persona he picked up along the way. He hit some kind of nerve with it. Dice shows are an event, a spectacle, kind of a religion. Everybody knows his material pretty much verbatim by now. They go to chant the jokes, those poems.”

I ask Paul if he finds the man funny. Watching the video, “The Diceman Cometh,” and listening to the 450,000-selling LP, “Dice,” it never occurred to me to laugh when someone calls a black woman with braces a “Black and Decker pecker wrecker” or recites:

Georgie Forgie pudding and pie,

Jerked off in his girlfriend’s eye.

When her eye was dry and shut,

Georgie fucked that one-eyed slut.

“It’s not really humor we’re going for,” Paul admits, including his girlfriend Christine as he swallows a quarter of the can. “We’re going to get shocked. With Dice, just when you’re going, ‘I’ve heard this shit before,’ he’ll hit you with something like, ‘Don’t move your ass so much, I’m trying to watch the ballgame,’ or, ‘You know the slob you’re eating is a pig when you can’t hear the stereo.’ You just can’t believe what you’re hearing. A lot of it,” he concludes, grinning about fat asses and stereos so widely he can’t polish off his beer, “is about women … sex and stuff.”

I ask Christine if she finds Dice offensive. She says “Nah” and Paul puts his hand around her shoulder. “She’s really liberal about stuff like that.” I ask Paul what he does for a living, and he suddenly looks dumbstruck. “I deliver furniture for a rich woman in the Slope,” he begins, the rest of his answer trailing off as he stands to admire a convoy of stretch limousines just inside the gates of the arena. The crowd outside the bus is packed so tight they seem joined at the shoulder. “Look at that,” he says to Christine. “Last time we saw Dice was in Town Hall, a year and a half ago,” he says, not really looking at me. “They were selling T-shirts with those dinky stick-on letters. See what they got now. Maybe this guy’s only a fad,” he tells me, “but he’s huge.”

Information on Dice Clay is kept scarce. Ascertaining his age from his L.A. publicity firm takes over an hour (he’s 32), and an embargo on interviews, press tickets, and cameras and tape recorders has been placed on this tour. The moves are ostensibly a reaction to his bad press, (“I wipe my fuckin’ ass with my fuckin’ reviews,” he now tells his audiences) but one can’t help but feel he’s terrified of having the veil lifted from the Face in the Crowd character he’s created.

“Andy’s been around a long time,” says Richie Tinken of New York’s Comic Strip. Dice Clay, he says, “underneath it all is a nice, hardworking Brooklyn Jewish boy who’s found a niche. He was doing all this material in a shirt and tie for years before he hit his gimmick. I seriously doubt he’s going to monkey with it now.”

I ask Tinken why Dice Clay’s hit so much bigger than a comic like Sam Kinison, who’s far more vicious—and funny. “Simple,” he says. “With Sam, you could tell he was genuinely enraged at something, blacks, Hispanics, women, whatever. He started out a preacher, or at least comes from a family of them. You know there’s something behind everything he says. But with Andy, you get the feeling, alright, he’ll put on his leather jacket, say a few nasty things about women, then go home and put on his normal clothes.”

Originally a drummer at bar mitzvahs, Clay entered show biz at the end of the Saturday Night Fever/Rocky craze, doing Travolta imitations at Brooklyn discos. He spent 10 years building a standup career and a following at increasingly big clubs, eventually falling under the wing of Mitzi Shore at The Comedy Store in L.A. Parts in four low-budget films culminated last year in an HBO comedy special that aired on New Year’s Eve, the starring role in a Bruce Willis-intended vehicle, Ford Fairlane (the trailer is shown at deafening volume before tonight’s show), and a spot on the MTV Awards, in which his obscene language earned him a lifetime ban from MTV, a lengthy disclaimer from the network, and 12 notches up the Billboard charts for his album. Pat Hoed, publicity director of the LP’s label, Def American, says Dice Clay spent most of his career “working one-liners and his dumb impressions [still part of the act]. He just flowered into this character about three or four years ago. Because he is doing a character.”

Eight permutations of the Dice “character” are selling (at $18 apiece) like six-packs at stands in the Byrne Arena tonight—black T-shirts showing Clay in a black T-shirt, jeans, shades, an array of ugly black leather jackets and holding, reaching for, or having just taken a drag of a Marlboro 100. Intended to portray him as a drug-free, slightly thinner Vegas Elvis (his hero), c. 1971, they seem more like the ultimate fantasy of a Rupert Pupkin—Scorsese/DeNiro’s caricature of a desperately hungry comic in The King of Comedy—somehow become flesh.

For each of these permutations, a thousand in-the-flesh variations are standing straight up, like a field of denim and leather asparagus stalks, against the walls or in the aisles of the arena, chain-smoking while their women wait on endless lines for the concession stands and bathrooms. A rather dapper specimen catches my eye: an immaculately coiffed blond man in his late twenties, wearing Guess jeans, paisley snakeskin boots, and a low-cut Danskin-looking T-shirt under a red, white, and blue leather jacket. A friend, Mussolini-sharp in a black turtleneck and a black acetate suit, gingerly pats the fine line of white-walled hair around his ears as he glares at me. On the back of his jacket is a cluster of gold studs spelling SUPPORT YOUR COUNTRY. I realize that I’m being rude, and tell them I’m just a reporter, taking notes. They both look like they’re dying to kick the shit out of me. I ask the blond man, whose name is Vince, what he thinks of Dice Clay.

Though Dice Clay never slips out of character, it becomes obvious that one is watching a “performance—not of some stereotype Brooklyn tough, but of the interior life of a man who’s in serious regression.

“Why you ask so many questions?” his friend demands.

“Let him do his fuckin’ job,” says Vince. “He’s a cub reporter. He’s going to make me famous.”

“Looks like a fuckin’ Jew to me,” his friend shoots out. I immediately calculate odds on getting in a sucker punch and getting out alive. Knowing I wouldn’t get five feet, I think to ask if he knows Dice Clay’s real name, then get a nasty inspiration. “What,” I ask, “do you do for a living?” It’s good for about two seconds.

“I work an appliances/electronics store. Assistant manager,” he adds, puffing himself back up. I ask Vince the same question, and he lights a cigarette. “I’m the other assistant manager,” he tells me, then urgently taps his friend’s shoulder, to check it out. A pretty woman, a bright red ribbon woven through a huge permanent, whizzes by with a Harry M. Stevens tray holding two franks and six beers. She begins to spill beer.

“Repulsive fuckin’ assholes!” she screams, not even bothering to turn around.

“Whew, she got some mouth,” Vince says admiringly.

A pair of wailing guitars, the intro to “Whipping Post,” calls everyone back to their seats, and a traffic jam forms at the gates to the seats. On the empty, black stage, I can make out a set-up for a 12-piece blues band, with two drum kits. The music, however, is coming from 10 overhead speakers—The Allman Brothers’ Live at Fillmore East—including a large amount of crowd noise from 20 years ago. The girl with the red ribbon is glaring, sandwiched between two guys with huge pecs under red T-shirts just in front of me. I tell her I’m just a reporter. She really does have some mouth.

“You guys write shit about Dice,” she lets me and several hundred people know. “You don’t know Thing One about it, and you nevuh, evuh, fuckin’ will. The man is rock and roll. The man has got a brilliant voice. The man has got the goods.”

I ask if the goods she’s referring to aren’t the same she just heard from Vince and his friend. The question seems to inspire her.

“Dice is a comic,” she says, turning off at her aisle. “Those guys are just a bunch of fuckin’ comedians.”

As Clay enters from the rear of the stage, backlit so he looks like Terminator on elephantine legs, the entire crowd’s on their feet and deafening. Gregg Allman starts singing

I’ve been run down

I’ve been lied to

And I don’t know why

I let that woman make me a fool …

Appropriately enough, Dice Clay raises his hand and snaps off the music at the lyric, “Sometimes I feel.” As he stands in the narrowest possible spotlight for a two-minute ovation, two enormous screens off the side of the stage show him in close-up, his face exultant and contemptuous: the only feelings, other than infantile oral aggression, that I’m going to see for the next hour.

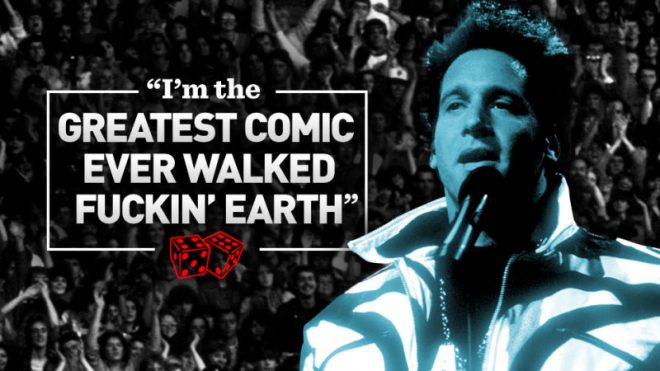

“So I’m doin’ this huh-mah-nicka solo on this litt-tle pig’s-s fudge flaps-s,” he breathes the first of his thick, emphatic consonants into the mike. He waits out another ovation before continuing with the little pig’s response, an insecure, whining, grating warble that is going to be tonight’s blanket “impersonation” of everything from women, to homeless men begging for a quarter, Geraldo Rivera, and Moonies. Ten minutes into the show, he delivers the punchline of his first actual joke, everything till now being either the assertion, “I’m the greatest comic ever walked fuckin’ earth,” or citations of people and situations he hates, followed by “Fuck you” or “Suck my dick.” Halfway through, I pick up what seems to be an echo in the speakers, then look around to see the entire arena chanting “trim that pussy, it’s so hairy,” a follow-the-bouncing-ball routine that continues for the ensuing half-hour of nursery rhymes modified to feature genitalia and anal sex, followed by some fantasies culled from masturbatory responses to his childhood TV shows (“OK, Jeannie, you wanna please your master? Make your tongue six feet long and lick my balls from across the fuckin’ room”).

Though Dice Clay never slips out of character, it becomes obvious that one is watching a “performance—not of some stereotype Brooklyn tough, but of the interior life of a man who’s in serious regression. After a strange, est-like sermon about Following Your Dreams (“Just like I did”), delivered half in “Dice” grunt, half in a recognizably different, pudgy-kid-in-the-back-of-the-class voice, the blues band is called onstage, and the real psychodrama begins. One last doff of the cap to the “Dice” character—a five-minute ditty with one lyric: “Suck my dick/and swallow the goo”—is all he needs to settle into the entertainment portion of the show, a painful rendition of “Love Won’t Let Me Wait,” which is followed by a blast of Led Zeppelin from the P.A. system.

For a full three minutes of “Rock ’n’ Roll,” the band members chant “D-I-C-E,” while Dice Clay does the rim of the stage, playing air-guitar and thrusting a fist into the air (the other holds an imaginary microphone), clearly lost in some fantasy of being both Robert Plant and Jimmy Page as he pumps the audience. While the music lowers, he runs triumphantly to the second drum kit for his show-stopping finale, a tap-for-tap cover of the entirety of the dueling drum solos on Santana’s “Soul Sacrifice” off the Woodstock album. Both video screens above the stage show Clay’s face for the whole number—living out his Sheepshead Bay basement fantasy, looking as blissful as Little Oscar drumming unseen beneath the bleachers during the Danzig rally.

Dice Clay runs to the front of the stage when the number ends, yells, “I’ll see you at the Garden in February,” and then charges offstage. The lights go up and the suddenly silent crowd files out to Blood Sweat & Tears singing “God bless the child that’s got his own” (the music programmed by Dice Clay). Stunned, I look around for someone to explain what I’ve just seen; I wind up looking at my watch, just for some bearings. The show’s lasted exactly 50 minutes. I count out the remaining days, hours, and minutes of this “low, dishonest decade,” and finally just get angry: Tomorrow afternoon, I realize, I’ll be paying my analyst half a day’s wages for the privilege of putting on the kind of performance this idiot’s making millions for.

This story is collected in No Success Like Failure.

Read Solotaroff’s follow-up to this piece, here.

[Illustration by Jim Cooke]