“I’m getting bored here,” Cameron is saying. “I went for popcorn 10 minutes ago.”

He is speaking into a handheld cordless microphone, his voice booming down from the astonishingly crisp overhead speakers like the voice of God. He is standing in water that comes up to his chest, surrounded by floating deck chairs and his crew and a few dozen extras sitting in lifeboats. Although he’s been doing this for the last five months, he doesn’t seem a bit tired. Looking into his monitors, he decides the light is too bright, notices an extra who isn’t looking in the right direction, sees a glare on the water, and taps at the camera monitor. “Josh, we gotta fix that,” he says.

Josh McLaglen is the assistant director, responsible for executing Cameron’s commands. He’s got the grim concentration of a man clinging to a ledge.

Another shot. Focus problem.

Another shot. “I didn’t feel that we were listening to the screaming that time, people,” Cameron says.

Another shot. Too much flashlight waving. “Do it like a cop, lock it to your body.”

Another shot. More attention-wandering extras. “Josh, I feel like I’m talking to myself here,” Cameron says. “Come over here and look at this—we’ve got to identify these people.” He taps the monitor. “Look. I don’t know what the hell she’s doing. She’s right in the middle of the shot and she’s wandering around the lifeboat.”

Josh answers in a clipped voice. “Yes, I see her.” The offending extra is dragged from the boat and shot. It had to be done. I think everyone watching at the time agreed. She was interfering with the mission. She was slowing Jim down.

You approach the Titanic set from a ticky-tacky stretch of undeveloped Mexican coastline. From a mile away you see the four Titanic “funnels.” The driver kills the lights as he passes the security gate into the Titanic “campus”—40 acres of instant movie studio, complete with three sound stages, a 32,000-foot wet stage with a 5 million-gallon tank, production offices, construction shops, dressing rooms, and various other buildings. All of this faces a six-acre, 17 million-gallon outdoor tank—the largest in the world.

It’s not a set. It’s a city. It’s so large there are lights on it to warn low-flying airplanes. In the center of it all, the Titanic. Built to 90 per-cent scale from the original plans, portholes gleaming against the black Pacific, it is a vast and magnificent thing, long as three football fields and tall as a great redwood. One chunk of it—weighing 1.3 million tons—rises up and down in the water on cue.

All this exists only because three and a half years ago, Jim Cameron popped a copy of the 1958 film A Night to Remember into his video player. Although taking on a historical theme would be a departure from the science fiction he’s known for, it was consistent with his long-standing fascination with apocalypse. Footage of the Titanic shot by oceanographer Robert Ballard had helped inspire Cameron’s 1989 movie, The Abyss, giving him the idea of shooting deep ocean as if it were outer space. He quickly wrote a 167-page treatment about the shipwreck that “signaled the end of the age of innocence, the gilded Edwardian age, where science would allow us to master the world….”

Then two studios teamed up to give him another $130 million or so to film it. They had no choice, really. Modern studios exist to create people like Jim Cameron, and he gives them back so much better than they deserve—they want Big Commercial Hit and he gives them Big Commercial Work of Art.

It flowed right out, and it was good—not only a rollicking disaster movie but a throbbing love story too, about a smart and “head-strong” 17-year-old who snubs her wealthy fiancé for a handsome young artist out of steerage class. He pitched it as “Romeo and Juliet on the Titanic,” and soon Fox gave him $3 million to dive down through two and a half miles of ocean to see the wreck itself—that was important to him. He ended up going down 12 times, filming the wreck with a crushproof camera that he designed with his engineer brother. But after five months of global research and tests with a 20-foot model and miniature lipstick video camera, Cameron decided he could only make the movie properly if he built his own studio—a job that required the cooperation of the Mexican government, various international construction companies, and five million pounds of steel. The Cameroids did it in just 100 days, working so fast they built one set on a cement pad and then put the soundstage up around it.

That alone cost something like $40 million.

Then two studios teamed up to give him another $130 million or so to film it. They had no choice, really. Modern studios exist to create people like Jim Cameron, and he gives them back so much better than they deserve—they want Big Commercial Hit and he gives them Big Commercial Work of Art. If they don’t give him the money, they might as well just kill themselves.

“Nice and quiet,” Jim says (no one on the crew thinks of calling him anything but Jim). “Here we go, rehearsal. And band.” This is back in January, on my first trip down to the set. The shot is Kate Winslet (the heroine) and Leonardo DiCaprio (the artist) running past the famous Titanic band.

“Guys, that speed was pretty good,” Jim says. “Why don’t you ratchet it up a half speed?”

With his hook nose and his Caesar haircut, Jim looks like the village smithy as drawn by a Dutch master—all he needs is a leather apron. He’s very alert and direct, ironic in an offhand way.

Another take. Jim doesn’t like the lighting. Or the crowd composition. Or the pace. “Have ‘em looking around, looking for options, not just with their eyes to the ground.”

Another take. The bass player was moving his bass too much.

Another take. There was a dead space.

Another take. Someone got jostled.

Another take. This time the violinist wants to change his line from “They never listen to us play, let’s play” to “They never listened to us at dinner either.”

“You mean it’s repetitious,” Jim says. “You mean the writer fucked up?” The actor hesitates. Jim wrote the script.

“Naw, go ahead and do it that way.”

Another take. A light balloon cuts out. “That’s three times we’ve been stopped by this balloon,” Jim says.

Another take. A timing problem.

Jim turns to Shelley Crawford, the script supervisor. “How many days are we into this?”

She doesn’t need to look. “One hundred and twelve,” she says.

“One hundred and twelve days and still running,” Jim says.

Back in L.A. and New York, Titanic rumors are already spreading. The first splash of notoriety came when someone—possibly a disgruntled crew member who couldn’t handle “Jim’s being Jim”—put angel dust in the soup, sending 80 people raving to the hospital. In London, there’s a story going around that Jim’s being Jim was too much Jim for some Mexican mafioso who got on the set, and now he has to have bodyguards at all times. Then the budget estimates jumped from $120 million to $160 million to $200 million. The two studios putting up the money, Paramount and Twentieth Century Fox, found themselves at odds as the budget climbed and the planned release date began to look like a fantasy.

Jim doesn’t care. “Every time I make a movie, everybody says it’s the most expensive film in the film industry,” he says.

One rumor is that when the suits came down to bug him, he smashed things until they left. This may or may not be true—I heard it from a Teamster on the set, and the story does have a certain Teamsterish ring—but it certainly fits the legend. Once, when a cheesy Italian producer dared to cut Jim’s footage to his own taste, Jim used a credit card to break into the editing room and recut the film. And that was back when he was a punk wannabe, years before the financial tsunamis generated by such movies as Terminator 2: Judgment Day and True Lies gave him clout equal to his chutzpah.

“I’m not into compromise,” Jim says. “But the film is definitely costing more than what we thought it was going to. I take responsibility for that. I told [News Corp. president] Peter Chernin and [News Corp. and Fox owner] Rupert Murdoch that I would give them back my entire salary, which I did. So I’m doing it for free.”

Jim says he feels pressure every day, anxiety at not making his deadlines and not planning things properly, but he sounds a lot more convincing when he talks about the excitement that pressure brings. “I like doing the kinds of things that other people can’t do,” he says. “So my attitude is, If you don’t like it, fuck you.”

He’s matter-of-fact about it, almost mild.

Jim wants lovers to be ripped apart. He wants children to be torn from fathers. “We also need to have people handing luggage in and then them handing it back out, saying ‘No luggage.’”

“Yes, sir,” says Josh. Tonight Josh is wearing black paratrooper boots and a paratrooper crew jacket from Broken Arrow, emulating Jim’s militaristic vibe. The martial tone is common here—a handful of crew members wear hats stitched with the legend CAMERON VETERAN, complete with military braid.

Nearby I hear a crew guy whisper: “I’m this fucking close right now. If they want to deploy six cameras right away, guess what? It’s not gonna happen in three minutes.”

Jim turns. “Where’s that fucking camera?”

Jim likes to shoot. Half the time his camera operators are standing around while he runs the camera himself—especially the handheld, which he begins using more and more as the Titanic starts sinking, going for the shaky-cam, “you are there” thing. Right now he’s got a camera on his shoulder but the return-feed cable is not working.

“All right, this is major,” he says. He turns to an actor. “Can I have your gun, please?”

The actor hands over his stunt gun. Jim points it at the cable tech. “Which kneecap do you want it in?” he says.

Black humor is the Cameroid style. One of the Titanic T-shirts displays the best on-set quotes: JIM’S A HANDS-ON DIRECTOR AND I HAVE THE BRUISES TO PROVE IT…. NO ANIMALS HURT DURING THE MAKING OF THIS FILM, BUT THE ACTORS WERE TOSSED AROUND LIKE STYROFOAM CUPS…. DON’T GET CREATIVE, I HATE THAT…. WAITING ON LIPSTICK? I SAY WE JUST TATTOO THEIR LIPS…. IT’S A TIMING THING, I DON’T CARE IF IT HAS ANY ORGANIC EMOTIONAL REALITY OR NOT…. YOU EITHER SHOOT IT MY WAY, OR YOU DO ANOTHER FUCKING MOVIE….

During lunch, Jim rides to his editing room in a van. He’s coediting the film on his breaks. “These days, with the editing technology we’ve got,” he says, “it’s almost faster just to do it yourself than to give somebody the notes and have them do it.”

The editing room, a simple office with computers and monitors, couldn’t be more unlike the set. As Jim watches the snippets of film flit by, he describes how computer-generated imagery will add dolphins, smoke and fog, fill out crowd scenes, and sew together splices in the screen image. In this room, in this mood, Jim is capable of peculiar detachment. There’s a chance, he says, that the movie will be “all things to everyone” or “nothing to anybody, not enough action for the action crowd, not enough romance for the romance crowd—a chocolate-covered cheeseburger.” He says this but he doesn’t seem very interested in it—it’s an amusing fact about life, nothing more. “I hope we make people feel like they’ve just had a good time,” he adds. “Not a good time in the sense that they’ve seen a Batman movie, but a good time in the sense that they’ve had their emotions kind of checked. The plumbing still works.”

The set’s almost ready, someone says.

“We want minutes,” Josh says. “That’s what Jim wants to hear, is it going to be five minutes?”

Jim picks up the walkie-talkie. “You think you can land on a fraction?” he says.

“I just think that having been on the real ship, it was really difficult for me to not do everything as right as possible,” he says.

Like four and a half minutes, he means—hell, he’d probably even prefer eighths and sixteenths.

He barely touches his food.

They’re loading a live weapon, using blanks, of course. Josh asks Jim what size charge he wants—from a full round to as little as an eighth round. The difference is the loudness.

“Who are you working for?” Jim asks.

“Make it a full one,” Josh says.

Jim is in the details. That’s why he had to shoot the actual sunken ship. “You could’ve made this movie without that, with regular effects,” he says. “It would’ve cost maybe two thirds of what it cost to go out and shoot it. But it wouldn’t have been the same movie.”

He means that literally. Going down to the wreck inspired haunting images of drowned grandeur, but it also gave him schematics. “I just think that having been on the real ship, it was really difficult for me to not do everything as right as possible,” he says. He ended up taking this to considerable extremes, down to getting his lifeboat davits and carpets made by the same companies, from the same plans, that made the Titanic originals. “We never violated what is known, to the best of my knowledge, except for a couple of really minor infractions,” he says.

I mention Oliver Stone. “Stone has an interesting philosophy,” Jim says. “His view is that history is so fucked up, it’s a consensus hallucination. So he will create an equal but opposite untruth to try to counteract the untruth that we live with. It’s a bullshit theory. I think if you just do what’s fuckin’ right and accurate to the best of your knowledge, it will ring true.”

Jim watches the monitors like a man reading the fine print in his contract with the devil. When the cameras are rolling, his mouth hangs open, he frowns, he stares. When the cameras stop, he’s got a thousand ideas. He doesn’t seem to notice when rain starts falling. “This is bad,” says Shelley the script supervisor, as drops hit her script. “Really bad.”

“Background! And action!”

The rain seems to jazz the actors. When they’re finished, applause breaks out. Jim watches the playback on the monitors. “Great,” he says. “Let’s do it again.”

In this scene, Leo and Billy Zane try to convince Kate to get on a lifeboat. Between interruptions, Jim gets a yellow sheet and a pencil and rewrites the dialogue on the rail of the ship. Zane’s line to Kate, “There are boats on the other side that are allowing men in,” becomes “I have an arrangement with an officer on the other side of the ship. Jack and I can get on, both of us.”

They’re ready to rehearse. “The trick here is to try to crowd the lens,” Jim says.

Then he notices that two actors are missing.

“Where the hell are Jason and Danny? They’re in this scene. What the fuck? Hel-loooo.”

Seconds later, the actors show up. “Guys, where the hell are you?”

‘We were just sitting in the…”

“Yeah, but we’re doing this scene.”

When they’re ready, Jim turns to Jimmy Muro, one of the camera operators. “It’s time to commit ourselves,” he says.

“Time to kill ourselves?”

Jim peers into his monitor. “I’d never do anything so merciful to you guys as kill myself,” he says.

This time the setup takes two hours. Cameras and crew hang off the side, shooting a dangling lifeboat. Then Jim gets in the lifeboat. “Give me the handheld with the 50,” he says. “Josh, when I finish this, I’d like to take another take of the jump so that I can start with something clean after we finish lunch.”

“Actually, lunch was an hour ago,” one of the crew members mutters.

Jim doesn’t hear. His brain is hardwired to ignore distractions. “Josh, what is going on? It’s taking them longer to lower that boat every time we do this.”

He turns to the stuntwoman. “Sarah, why such a long pause between your cross and your jump? It’s not about pausing to take a great jump, it’s about one continuous move.”

And back: “Josh, have you talked to Simon about timing these stunt falls?”

This is what always happens. Jim’s shots always get more and more complicated, until he approaches what cinematographer Russ Carpenter calls a controlled frenzy. It is more or less intentionally disturbing. “I think that Jim consciously builds that into the shooting environment, so that we’re all working more or less off balance—being in awkward positions, new elements added at the last moment. It keeps everybody on their toes.”

He says this with an easygoing smile. But then another cinematographer disagreed with Jim a few too many times and was lost in the North Atlantic….

Now for Leo’s reaction shot. “What should I be doing here?” Leo asks. He’s impish, constantly caressing a cigarette.

“You don’t know that she’s gonna jump until she jumps,” Jim says, “so it’s more like ‘No, no, no, no, what are you doing?’ It’s like you can’t fucking believe it.”

“But I can see it in her face,” Leo objects. Although he generally appears well behaved, Leo seems to act the bad boy with Jim. In response, Jim falls into what seems—in my presence—like genial ribbing. “Every time we’re about to do water work, Leo gets sick,” he says. Another time, he wonders what important new shipment of video games has evidently delayed Mr. DiCaprio’s arrival to the set. But here at least, any mention of the rumors of star-director strife zipping around the cell phones of L.A. are met with the usual Jim-über-alles response. “He’s the coach that you want to please, and he’s going to kick your ass,” says actor Billy Zane, “but he’ll be the first to pop the champagne in the locker room.”

Later, when I catch up with Winslet on the phone, she says that Leo was a brilliant god of acting and that he and Jim got along great and ventures into personal complaint this far and not one inch further: “I’m a bit of a masochist, so in many ways the cold water was kind of useful.” Any other thing she may have been quoted as saying—like that bit in a Los Angeles Times interview, in which she said that “if anything was the slightest bit wrong (Jim) would lose it…shouting and screaming”—was out of context or the product of exhaustion.

Still, it is hard to forget the famous quote Ed Harris gave Premiere reporter Fred Schruers after playing the lead role in Cameron’s last water epic: “I’m not talking about The Abyss and I never will.” And I cannot tell you why DiCaprio refused, months later, the follow-up interview he’d promised, although I heard that he was very busy pursuing a night life in the New York clubs at the time.

But on the set, at this particular moment, Cameron repeats his point, and then shrugs. “Just decide what makes sense to you. We can do it both ways.”

“I’ll just see what happens,” Leo says.

Just before I leave, Jim says he wants me to come back and see him shoot an intimate scene. I’ve heard from the crew that he’s spending a lot more time on the romance than on the action, which brings up the contrast between gearhead control freak Jim and the Pucciniesque romantic who wrote The Abyss.

“I like using hard-core technological means to create an emotion,” Jim explains. “That’s what most fascinates me about this project—nothing thrills me more than being on a green-screen stage on some complex crane rig during a moment that is so delicate emotionally that if you get that part of it wrong, all that other stuff is for nothing. Like the scene where he’s at the bow of the ship after she’s told him that she can’t see him, and he’s just sitting there, kind of morose, thinking about that with the wind blowing through his hair, and she walks up behind him and just sort of appears there, out of focus, and says ‘I changed my mind.’ His whole life turns on that one moment, and to get it we had to build a ship that didn’t exist anymore….”

Listening to him, I realize that the pivotal Cameronian moment is the scene in T2 when Linda Hamilton looks at the Terminator as he plays with her son and realizes that a machine is a better father than any of the flesh-and-blood men she’s dated—he never tires, never gets bored, never gets drunk. He’s RoboDaddy, created by RoboJim.

By 6:00 a.m., the first gray streaks lighten the horizon.

“After this,” Josh asks, “is this gonna be it?”

“Of course not,” Jim says. “I’ve still got the technocrane stuff to do. You gotta crack.”

Ten minutes later there’s a line of light creeping above the mountains. “That’s 10 million volts coming up,” Jim says. “Let’s go—we got time for one more.”

Kate turns that haunted look on Leo, cries a little bit….

“You gotta remember, the women on the Titanic had never been in a lifeboat,” Jim tells the extras. “They were terrified, they were petrified. Okay, now let’s try it again.”

The sky is pale blue now.

“Entropy,” says Jim.

Someone asks what it means. Jim supplies the answer: “It’s the tendency of complex systems to degenerate into disorganization.”

That was January. When I left, they were supposed to wrap on February 24. But now it’s March 14 and they’re still shooting. They’ve been shooting nights for three months, wrapping long after dawn most mornings, seven days a week for weeks, with 200 or 300 extras and dozens of stunt people and water and the cold air blowing off the ocean. People are tense. They want to go home. Hernando the driver says two security guards got into a fight.

Up above, there’s a beautiful crescent moon. Out in the big tank, deck chairs float in the water. A guy comes paddling by on a kayak, bearing food. The makeup women carry their makeup in plastic trays floating on top of the water. Extras stand amid the debris like something out of a painting by Magritte. Ocean fog rolls in. Whenever they can, people unzip their dry suits and pull their heads free, like big hairy mussels in black shells. They talk about how great the dailies are, how good morale is now that they have just a few more days left.

And Jim picks up his microphone: “A thousand screaming people,” he says. “Think about what that means—that’s the entire population of the town I grew up in, all dying at the same time. They’re calling for help. You have four lifeboats. You could go back and help them. But there’s a thousand of them, and they could swarm over that boat and pull it down so fast it would kill you all. So there’s an emotion here. There’s a conflict. This is what you’re acting.”

Jim says all this nicely. He’s merely giving them the information they need to do the job. “Right now they can’t act anything,” says Shelley. “Their bladders are full.” Shelley has been standing in the water for hours, a boat ride away from the nearest bathroom.

Jim is famous for how tough he is on his crews, and people are saying he’s in Mexico at least partly because there are no unions and people will work their asses off for $20 a day.

Jim calls action.

This time we hear actual screaming in the distance—dozens of people standing on the pier to add a touch of realism. “It sounds like Magic Mountain back there,” Jim laughs.

I notice a couple of extras glaring at him.

Another take. And another. People are starting to look haunted. Then Jim needs a continuity reference. He turns to look for…

“Shelley?”

“She went to the rest room.”

“Perfect,” Jim says. “Everything grinds to a halt while the one person who has the reference is gone.”

I like Shelley. Those quiet, wry types get to me. But I think we can all agree: She should have held it in.

Tonight there’s a rumor that Jim might wrap early, since it’s Sunday and all. But right now it’s 4:00 a.m. and he’s lying in the bottom of a boat and nobody has much hope. “He’s just not going to go for it,” says Jimmy the steadicam operator.

Yesterday they shot till 8:00 a.m. Came back after a big 11-hour break. On a Sunday.

Kate Winslet is lying in the bottom of the boat, doing a very convincing imitation of someone exhausted beyond grief.

“Very nice,” Jim says.

The joke on the set is, they’re hoping Jim will give them July 2 off—so they can go to the movie. There’s some dubious, queasy laughter around this joke even now, as if they know that they will miss the July 2 date and then the July 18 date and then July 25 and then…

“In the end it will be just Jim with the camera,” says Jimmy, “and the suits will be trying to pull him away, and he’ll be, ‘Give me that camera.’”

The Titanic is sinking. The water wraps around your legs like liquid lead, so cold and heavy. It’s squirting in the door, percolating right through the floor, gushing up a foot a second. A wall of green water rises in the wheelhouse windows as Captain Smith stands with one hand on the wheel….

“Cut,” Jim says, and instantly the water recedes. In seconds it’s below the knees. We’re on the riser set. Silent hydraulics lift us, plus a million-point-three pounds of fancy carpentry.

“The water didn’t hit its mark,” Jim says. “It’s foggy and we don’t give a fuck.”

He gets the shot in a few takes, then moves to the “dump tank” set. In this scene, a wall of water rushes down a hallway, sweeping away a man and his baby boy. The hallway leans on the side of a hill; the crew has been building a sluiceway out of plywood for the water.

Jim shows Jimmy Muro where he wants the camera—right in front of the rushing water. “Just before the water hits, they’ll pull the camera up and you hold on to the strap.” They do a test. Ten feet of water roils through, practically steaming, washing the stuntman down the road at least 200 feet. Muro seems a little dubious. So Jim says fine, he’ll operate the camera himself.

Take One. The water hits the stuntman so hard that his dummy son gets knocked out of his arms. Jim climbs out of the sluiceway in his wetsuit and studies the monitor. “I don’t know,” Jim says. “Seeing that kid hit the wall like that is kind of bad….”

They have to do it again.

Jim is famous for how tough he is on his crews, and people are saying he’s in Mexico at least partly because there are no unions and people will work their asses off for $20 a day. But the core members of his crew seem fond of him, in a rueful, hostage-situation kind of way. “Jim puts the hurdle very high, so you feel a strange exhilaration when you jump over it,” Shelley says.

“He’ll be real happy to tell you if you missed your assignment,” says Russ Carpenter, grinning.

Jim’s yelling is a frequent subject. “I can’t even tell the difference between yelling and not yelling anymore,” Shelley says. “It’s just, ‘What does he want and what do we have to do to get it done?’” But things are a little better when there’s a journalist around, she says. “Sometimes we joke—‘Can’t we just hire an extra and tell Jim that it’s a reporter?’”

When I ask Shelley if she likes Jim, she hesitates for just a second. “It’s unpopular to like him here,” she says. But then she says she likes him a lot. “The other day, when they were doing the funnel drop, he says, ‘Chuck, what do we have to do to get this right, sacrifice another chicken?’ How can you not like that?”

But after six months, she’s still puzzled: “Why does he do it?” she asks. “Why does everything have to be perfect? Why does the wave have to be four feet and not two feet? Why does the amplitude have to be exact? How does he decide? Why is bigger always better? What drives him?”

“There was a week maybe three weeks ago where everybody hit a slump at the same time,” Jim says. “Everybody. Me, Josh, the AD department, the effects department. We were the walking dead. It was the funniest thing I ever saw. Russ fell asleep on the set. Everybody was stumbling, dropping things, breaking equipment. It was like the PCP thing in Canada, except not drug induced. And then everybody just hit that wall and went through it. They’ve been fine since. Everybody just has to look inside themselves to get the heart to go on and then you just do.”

It’s time to deal with some of the rumors. Yes, one person died, but off the set, in a drunk-driving accident. The Mexican-mafioso story appears to be bullshit. It’s true that the Mexican laborers are getting just $20 a day, but that’s double the going rate there. As far as general fatigue-generated illness, paramedic Ed Houston tells me he’s dealt mostly with respiratory infections, flus, fevers and stomach problems, diarrhea. There have been a few broken bones—one snapped ankle, some fractured ribs, a Dutch elbow—and a couple of serious head injuries during construction, but what do you expect on a project this size? Aside from that, it’s mostly hypothermia. “If they start to shiver violently, we take them out of the water right away.”

That’s the last I write or ask about yelling or unfairness or the occasional totally justified execution. I don’t want to distract Jim. Don’t people understand he’s on a mission?

At dinner, Jim shifts instantly from highly technical issues to sentimental concerns. Like the gender themes in the movie, which pivot on “the end of the Edwardian age and the death of the old, overt repression of women, and the beginning of a more covert repression of women.” Or the impact of seeing Doctor Zhivago as a teenager: “I always wanted to make a movie like that. Even before I knew I wanted to be a filmmaker, I thought, What a great film. I didn’t know what it was about—I thought it was about a doctor. I went back every night that week. I just loved the grandeur, the emotion, the music. I loved everything about it.”

At times like this, he’s totally normal and relaxed, just a guy talking about his version of cool stuff. The only odd note comes when he talks about our delusions of technological control, his ongoing theme since Piranha II: The Spawning. “Here we are, we’re all on this big ship and we think we’re in control and we’re not—if all the microchips on the planet stopped working right now, we would be gnawing on each other’s femurs within two weeks.”

Notice the touch of relish?

One afternoon I see Josh at the hotel, frozen on a staircase. He has slipped into another dimension. When I say hello, he looks at me with glazed eyes. “I’m exhausted,” he says.

Josh has lost about 20 pounds since shooting started.

Finally it’s time for my love scene. It’s scheduled for the first half of a night, so I’ll be able to go back to the hotel and get some sleep before the plane. When I arrive, I find Jim showing Kate and Leo the partial edit of the scene so far. “This is where I need the close-up,” he says. “Then a couple of green-screened shots, and a shot where you’re stepping on the rail.”

They’ve already done the scene twice, once on the big Titanic set and once in L.A. in front of a green-screen. Now they’ve painted a wraparound sunset to match the original live sunset and built a 30-foot chunk of ship’s bow, plus (across the soundstage) a small version of the superstructure of the ship’s bridge to create an illusion of depth. There’s even a little puppet captain.

After a while, Jim gets a little romantic: “Ideally, this is the most natural of the shots because there’s no ship at all,” he tells the actors. “It’s just you two in the ocean.”

Later he tells me he’s always drawn to the bow of a ship because that’s “where rubber hits the road.” He goes on about it a little bit, so I ask if he ever did anything like this scene in real life. “I did it on a building in New York,” he says.

Oh? With whom?

“I think everybody has these epiphany moments in their lives,” he says.

Exactly. So give it up.

“I’m not talking about it,” he says. “I’ll get in trouble.”

Last-minute adjustments: Too much light on the rail, the wind is blowing Kate’s collar. Jim sits on a platform off the bow, staring at his monitor. “Let’s go from 60 to 70 and then there’ll be more differential focus,” he says.

Several rehearsals.

“I like this one better than the last one because he started to say something and then he realized that it doesn’t matter.” Jim says. “It’s, like, you don’t have to say anything.”

And finally they’re ready to start shooting. Jim cracks: “Four hours of breathless anticipation directly into the first shot of the day.”

Action. Kate steps forward. “I changed my mind,” she says. Leo reaches out his hands….

Cut. “That sucks,” Jim says.

A flurry of adjustments, from the angle of the stage sun to dulling spray on a gleaming anchor. Jim switches to a longer lens to make things shakier, then grabs a paintbrush and climbs up to the bow and starts painting a few delicate rust streaks on the forward cleat. The standby artist hovers right behind him.

Another take. “Kate, it feels like you’re too ready. Let him be surprising you a little. Like you’re taking it in. More wonder.”

Lots of energy this time, all the way through to a passionate kiss. Her hand goes behind his neck. It’s very romantic.

Cut. “Leo, more effort, you’re talking her into doing something,” Jim says.

Kate asks how many takes Jim has in mind. “No more than 10,” Jim says.

“Definitely no more than 21,” she teases.

An hour passes.

Another hour passes. Then comes the moment Jim wanted me to see. “The thing that’s interesting about this moment is when he says, ‘Close your eyes,’” Jim tells Kate. “Cause you already made your decision to break with your other life. So there’s this big trust going in. But there’s also that mystery—you’re going into the unknown.”

“I’m kind of trying to play, Well, is he going to kiss me?”

“You can put that in there as well. But I don’t want to see apprehension. It’s, like, ‘Okay, you’re crazy, but I want your craziness, I want to let it inspire the craziness that I know I have.’”

That’s it. Now I get it. All this massive Titania and Jimology aimed at this moment, total control opening the door to total freedom.

“Let’s do one a little more tremulous.”

Okay, maybe that’s not it.

A radio goes off.

“Goddammit!” Jim says. “Radios off, everybody.”

Take 12. Very tremulous.

“Now let’s try one with more intrigue.”

Take 13. Very intrigous.

Then I get it: The point isn’t the moment of craziness but the work it takes to get there. As if to drive the point home, Kate gives Jim exactly what he’s been after, a very subtle smile of shy surrender. She’s magnificent.

“Leo, I don’t feel that you’re reacting to her,” Jim says.

Take 14. “One more for luck,” Jim says.

Take 15. “This is basically the lovemaking scene,” Jim tells Leo. “If there’s one woman on the planet left who doesn’t want to fuck you—one Eskimo in the Yukon who just got a TV—she will after this.”

Take 17. “Just kind of get closer to her so her hair is in your face and you smell her, you know what I mean? Get a little closer to her.”

When Jim calls cut, Leo breaks from the kiss, blowing off imaginary steam. “Ooh, boy,” he laughs.

Jim turns to Kate. “Kate, some of the joyful discovery has gone out of it. So why don’t you bring a little of that back now that you’ve got all the modulations?”

Finally, Jim’s finished. “Precision kissing,” he says.

4:00 a.m.: They turn the bow around to get Leo’s close-ups against the same backdrop.

5:00 a.m.: Russ relights the scene to make it look “more like a wild environment.”

5:20 a.m.: Kate looks sick. Since she’s wearing a tight corset, she hasn’t eaten a full meal for 12 hours.

5:25 a.m.: Jim doesn’t like Leo’s hair. He calls for goop and starts fixing it himself.

5:45 a.m.: Kate and Leo come face to face, and Kate—strikingly beautiful, her exhausted pallor so right for the scene—takes hold of his shirt, a small but enormously touching gesture.

6:00 a.m.: They pull the green screen into position. Jim composes a shot of Kate, her arms spread in flying position, finding a skewed angle that gives it the perfect wild energy.

6:10 a.m.: Jim and Landau talk about the next setup, which is complicated by fog and drainage questions. “This is what happens when you get down to stems and seeds on a movie,” Jim says.

7:05 a.m.: They’re still shooting the green screen. “Two problems,” Jim says, approaching Kate.

7:20 a.m.: I have to catch my plane. “Oh, you’re punkin’ out,” Jim says.

They’re still shooting when I leave.

I’m not worthy. I know that now. I’m much too weak.

But then Larry the Teamster starts gassing on. He says Jim’s been keeping the extras in the water so long they’ve been getting sick. And Jim told the West-cam operator that he was going to kick his teeth in. And grabbed another guy by the collar and shook him. The guy may be a genius but he’s just too damn abusive—why, on T2-3D, the whole electrical crew quit one night because it was just too damn dangerous….

There’s only one thing to do. I think you’ll agree.

I leave his body by the side of the road.

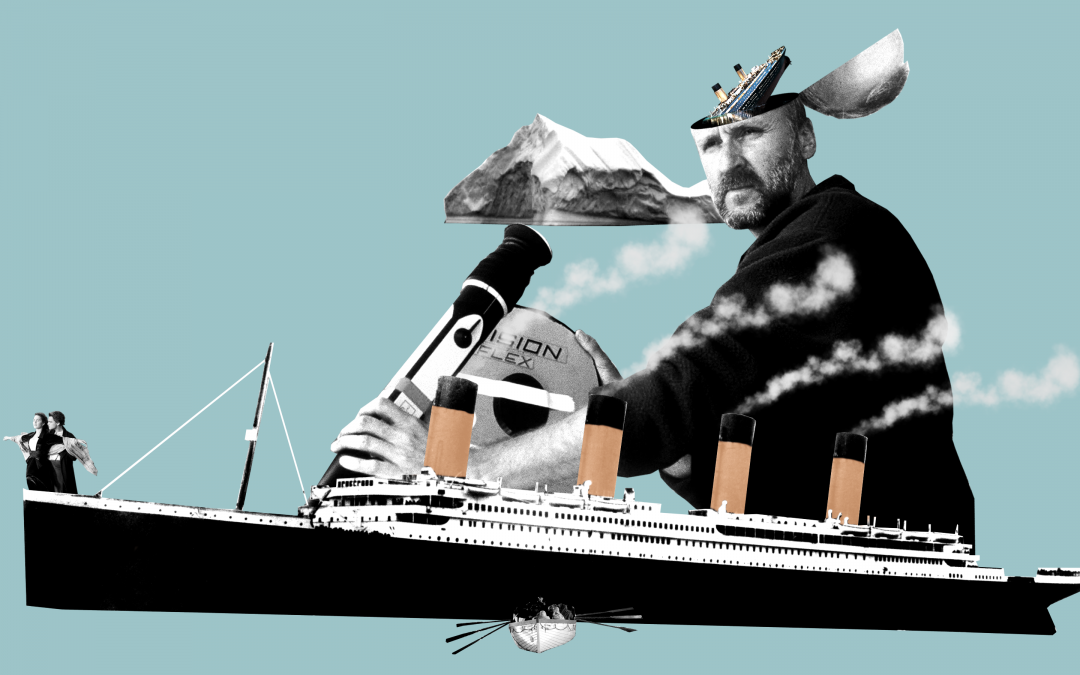

[Photo Illustration by Elena Scotti/Deadspin/GMG]