“The rich,” according to a Spanish proverb, “laugh carefully.” They have a lot to lose. The poor, on the other hand, need to laugh in order to forget how little they have to laugh about—which may be why the Depression was the last golden age of comedy in American movies. Will the current economic recession bring on another comedy boom? Movie producers think so; the 1975 production docket is packed with laugh-it-up scripts. Film producers also acknowledge that the strongest creative impulse behind the boom is the maniacal imagination and energy of one of the very few moviemakers since Charlie Chaplin who is unarguably a comic genius—Mel Brooks.

Brooks is an American Rabelais. Short and blocky, he has a nose once described as “a small mudslide,” a grin that loops almost from ear to ear like a tenement laundry line and the flat-out energy of a buffalo stampede. His imagination is violent and boundless; and in the opinion of other comedy writers, no brain on the planet contains such a churning profusion of wildly funny ideas.

Brad Darrach, a freelance journalist, was assigned by PLAYBOY to interview Brooks. Brooks was flattered by our request. As the subject of a previous “Playboy Interview” (October 1966), he was about to become the first person ever interviewed twice by the magazine. Nevertheless, though always friendly and charming, Brooks flatly refused at first to discuss any aspect of his private life and, for more than a month after Darrach arrived in Hollywood, said he was too busy editing Young Frankenstein to take any time out for formal interviews. He allowed Darrach to watch the editing process, however, and gradually admitted him to his working family. Here is Darrach’s report:

“After five weeks, the interviews began. They were held at Brooks’s office, a large smog-soiled rectangle in 20th Century-Fox’s main office building. We had 12 sessions in all, over a period of three weeks, beginning every day at about 11:45 and lasting until about one. For the first session, Brooks’s secretary, Sherry Falk, and I assembled an audience of writers, directors, producers and their secretaries. After that, there was no need to stimulate attendance. Swiveling and grinning behind his big curved paper-cluttered desk, leaping up and shouting and mugging and scrambling around the room as he spouted sense and nonsense, Brooks had his listeners literally falling out of their chairs almost from the first word of the interview. Hearing the ruckus, people came running from all over the building. During every session, 15 or 20 people would wander in and out, while a half-dozen stood grinning at the door. To preserve the frenetic flavor of the scene, I have left in the interview a few of these interruptions. In the last two recording sessions, which were conducted in private, Brooks finally revealed details of his personal life and made the powerful statements about himself and his philosophy that conclude the interview. ‘I hope you got enough,’ he said when the last session was over. ‘My tongue just died. PLAYBOY’s gonna have to pay for the funeral and put up a statue of Mel Brooks’s tongue in Central Park.’”

BROOKS (sucking up a fistful of chocolate-covered Raisinets and chomping them behind a Brooklyn-street-kid grin): All right, ask away, Jew boy, or whatever you pretend you are.

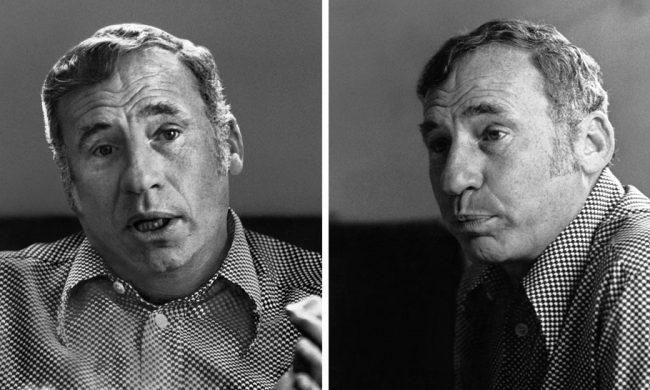

PLAYBOY: As one Episcopalian to another, how about giving our readers some idea of what you really look like? There will be three pictures of you on the first page of this interview, but they won’t do you justice.

BROOKS: I don’t want to be vain, but I might as well be honest. I’m crowding six-one. Got a mass of straight blond hair coming to a widow’s peak close to the eyes. Sensational steel-blue eyes, bluer than Newman’s. Muscular but whimpy, like Redford. The only trouble is I have no ass.

PLAYBOY: What happened to it?

BROOKS: It fell off during the war. Now I have a United Fruit box in the back and I shit pears.

PLAYBOY: Tell us about your ears.

BROOKS: My ears are very much like Leonard Nimoy’s—you know, Mr. Spock on Star Trek, the guy whose ears come to a point. It happened like this: One night Leonard and I went out and before dinner we had 35 margaritas. We woke up in a kennel. There were four great Danes, two on each side of us. Their ears had already been clipped. And so had Leonard’s. I reached up, felt my ears and, alas, mine had, too.

PLAYBOY: What about your nose?

BROOKS: What about yours? Mine is aquiline, lacking only a little bulb at the end.

PLAYBOY: You wish you had a bulb?

BROOKS: I do, I do—one that said 60 watts on it and lit up. It would attract moths. And it would help me read at night under the blankets at summer camp. Care for a Raisinet? We mentioned Raisinets in Blazing Saddles and now the company sends me a gross of them every month. A gross of Raisinets! Take 50 boxes. My friends are avoiding me. I’m the leading cause of diabetes in California. Seriously, they make great earplugs. Or you could start a new school of Raisinet sculpture. No? Did you know that PLAYBOY in Yiddish is Spielboychick? Is it true that I am the only person who has ever been interviewed twice (ear-piercing whistle) by PLAYBOY?

PLAYBOY: Yes, and we’re beginning to think we’ve made a terrible mistake. To what, by the way, do you attribute this distinction?

BROOKS: To my height. And the lack of it.

PLAYBOY: Since you’ve brought it up, why are you so short?

BROOKS: You mean all of me or parts of me? OK, you want me to admit I’m a four-foot, six-inch freckle-faced person of Jewish extraction? I admit it. All but the extraction. But being short never bothered me for three seconds. The rest of the time I wanted to commit suicide.

PLAYBOY: Now we know what you look like. What do you do for a living?

BROOKS: I make people laugh for a living. I believe I can say objectively that what I do I do as well as anybody. Just say I’m one of the best broken-field runners that ever lived. I started in ’38 and I’m hot in ’75. For 35 years I was a cult hero, an underground funny. First I was a comic’s comic, then I was a comedy writer’s comedy writer. When I’d go to where they were working, famous comedians would turn white. “My God, he’s here! The Master!” But I was never a big name to the public. And then suddenly I surfaced. Blazing Saddles made me famous. Madman Brooks. More laughs per minute than any other movie ever made—until Young Frankenstein, that is.

PLAYBOY: What’s so special about your comedy?

BROOKS (snatching up the receiver as the phone rings): This is Mel Brooks. We want 73 party hats, 400 balloons, a cake for 125 and any of the girls that are available in those costumes you sent up before. Thank you! (Slams the receiver down) You were saying?

PLAYBOY: What’s so special about—

BROOKS: My comedy is midnight blue. Not black comedy—I like people too much. Midnight blue, and you can make it into a peacoat if you’re on watch on the bow of a ship plowing through the North Atlantic. The buttons are very black and very shiny and very large.

PLAYBOY: Speaking of blue, you’ve been accused of vulgarity.

BROOKS: Bullshit!

PLAYBOY: And of being undisciplined in the comedy you write and direct.

BROOKS: Anarchic, the crickets call it. My mother says, “An archie?” She think I’m an architect. My comedy is big-city, Jewish, whatever I am. Energetic. Nervous. Crazy. Anyway, what do PLAYBOY readers care about comedy? They’re not reading this interview. They’re all sitting on the toilet with the centerfold open, doing God knows what.

PLAYBOY: How did you come by your sense of humor?

BROOKS: Found it at South Third and Hooper. It was in a tiny package wrapped in electrical tape and labeled GOOD HUMOR. When I opened it up, out jumped a big Jewish genie. “lll give you three wishes,” he said. “Uh, make it two.”

PLAYBOY: Where was South Third and Hooper?

BROOKS: Brooklyn. I was born in Brooklyn on June 28, 1926, the 12th anniversary of the blowing up of Archduke Ferdinand of Austria. We lived at 515 Powell Street, in a tenement. I was born on the kitchen table. We were so poor my mother couldn’t afford to have me; the lady next door gave birth to me. My real name was Melvin Kaminsky. I changed it to Brooks because Kaminsky wouldn’t fit on a drum. My mother’s maiden name was Kate Brookman. She was born in Kiev. My father was born in Danzig. Maximilian Kaminsky. He was a process server and he died when I was two and a half—tuberculosis of the kidney. They didn’t know how to knock it out, no antibiotics then. To this day, my mother feels guilty about us being orphans at such early ages.

PLAYBOY: What’s your mother like?

BROOKS: Mother is very short—four-eleven. She could walk under tables and never hit her head. She was a true heroine. She was left with four boys and, no income, so she got a job in the Garment District. Worked the normal ten-hour day and then brought work home. Turned out bathing-suit sashes until daylight, grabbed a few hours of sleep, got us up and off to school and then went to work again.

PLAYBOY: Did your mother have time to look after you?

BROOKS: I was adored. I was always in the air, hurled up and kissed and thrown in the air again. Until I was six, my feet didn’t touch the ground. “Look at those eyes! That nose! Those lips! That tooth! Get that child away from me, quick! I’ll eat him!” Giving that up was very difficult later on in life.

My mother was the best cook in the world. “I make a matzoh ball,” she used to say, “that will sweep you off your feet!” And she did her piecework in the kitchen, too. All night she would sit up sewing, pressing rhinestones, going blind. Wonderful woman! She’s 78 now and still running to catch planes. I took her to Las Vegas not long ago. She loved the lobbies, to hell with the big stars and the gambling. She liked the lobbies. Jews like lobbies.

PLAYBOY: Did you get your sense of humor from your mother?

BROOKS: More from my grandmother. She could hardly speak English, but she made up bilingual jokes. “Melbn? Es var a yenge mann gegange for a physical, OK?” A young man went for his Army physical. “Geht zurick und sagt, ‘Momma, ich bin Vun-A!’” Tells his mother he’s One-A. “Momma hat gejumped in the air mit joy. ‘Vunderbar! You vouldn’t go!’” “But, Momma! One-A means perfect! I go!” “Bubele! Vat you talking? How dey can teck you mit Vun-A?” Well, the joke was, I discovered finally, that A sounds like ei in Yiddish. Ei means egg, and egg means testicle. How ‘bout that for Grandma?

PLAYBOY: Not bad. Do you have any other—

BROOKS: Freeze! Don’t move! Time for a well-known Quotation from Chairman Mel’s 2013-Year-Old Man record. Ta-daaaa! “IF PRESIDENTS DON’T DO IT TO THEIR WIVES—THEY’LL DO IT TO THE COUNTRY!” You were saying?

PLAYBOY: Any other memorable relatives?

BROOKS: Yes, Uncle Joe, Uncle Joe was a philosopher, very deep, very serious. “Never eat chocolate after chick’n,” he’d tell us, wagging his finger. “Don’t buy a cardboard belt,” he’d say. Or he’d warn us—we’re five years old—“Don’t invest. Put da money inna bank. Even the land could sink.” He’d come up and tap you on the arm while you were playing stickball. “Marry a fat goil,” he’d whisper. “They strong. Woik f’ya. Don’t marry a face. Put ya under.” He had great similes. “Clever as a chick’n” was one of them. “That guy’s got da eyes of a bat. Never misses!” Later, we’re in our teens, we’re horsing around outside the candy store, he’d come up to us. “What you talk’ ‘bout, boys?” “New cars.” “Hmmmm.” He’d stroke his chin. “As far as I’m consoined,” he’d say finally, “dey all good!”

PLAYBOY: Did you ever run away from home?

BROOKS: I don’t think Jewish boys did that. Run away to what? But we hitchhiked a lot across the Williamsburg Bridge in search of jobs. We’re 11 and we’re going to get jobs in New York. So we’d walk around the Lower East Side and for four cents we’d buy a ton of sauerkraut and gorge ourselves and be very sick. Then we’d walk back; nobody would give you a ride at night. It was a 20-minute walk over the bridge. Somewhere over the middle, we’d get scared and begin running. Six hundred feet below is water—right—and Jews on both sides. If you fell in, who would rescue you? Jews in those days couldn’t swim.

PLAYBOY: Why not?

BROOKS: Only place to swim was McCarren Park, which was in a gentile region of Brooklyn. We could only go there if there were six to twelve of us. Otherwise, we’d be attacked. Like, we’d be in the locker room and a gang of Irish or Polish or Italian kids would be there and they’d inspect you. They’d see you were circumcised, so they knew who was what. In those days, gentile kids were not circumcised. Then they’d follow you out and pick on you.

PLAYBOY: Did you carry weapons?

BROOKS: Never. Because then they’d panic and get a hundred people. No weapons in those days.

PLAYBOY: Did you ever commit a crime?

BROOKS: Yes. I stole salt off pretzels in Feingold’s candy store.

PLAYBOY: You were a wild kid.

BROOKS: Not only that, there were Penny Picks—chocolate-covered candy, white inside. If you got one that was pink inside, you got a nickel’s worth of candy free. We would scratch the bottom of the chocolate with our thumbnails until we found a pinkie. Poor Mr. Feingold. He could never figure out how we found so many pink ones. Which reminds me—Raisinet? Take two.

PLAYBOY: No, thanks. No juvenile offenders in your neighborhood?

BROOKS: Sure, me! There were these Japanese yo-yo experts who used to do exhibitions at the Woolworth. They were great and even the managers would take their eyes off the counters to watch them “walk the dog” and “skinny up a pole” and all that. “Ok,” we’d say, “the coast is clear.” Then we’d steal something. One time I was with Muscles Mandel and I was caught lifting a 20-cent cap pistol. The manager grabbed me and said, “Gotcha!” I ripped the gun around and said, “Stand back or I’ll blow your head off!” He jumped back. Everybody jumped back, and with this toy gun I made my getaway—stealing the gun at the same time! Those idiots! They knew it was a cap gun and still they backed up! I used that gag later in Blazing Saddles. What the —— (Brooks looks up, startled. An actor wearing a “Planet of the Apes” mask is strolling down the corridor outside Brooks’s office, as though there were nothing in the least unusual about his appearance. He glances casually into Brooks’s office. Just as casually, Brooks gives him a nod.)

Hiya, kid. Workin’? (The actor does a startled take, then moves on.)

PLAYBOY: What were you good at in school?

BROOKS: Emoting. When I had to read a composition, I would turn into a wild-eyed maniac, fling out my arms and announce in a ringing soprano: “MY DAY AT CAMP!”

PLAYBOY: What were your favorite books?

BROOKS: Dirty comics. Eight pagers. Short attention span. No. Actually, I liked Robinson Crusoe, Black Beauty, the usual things. But I wasn’t a big reader. Couldn’t sit still long enough.

PLAYBOY: How about Hebrew school?

BROOKS: Shul, we called it. I went for a little while. About 45 minutes. We were the children of immigrants. They told us religious life was important, so we bought what they told us. We faked it, nodded like we were praying. Learned enough Hebrew to get through a bar mitzvah. Hebrew is a very hard language for Jews. And we suffered the incredible breath of those old rabbis. They’d turn to you and they’d say, “Melbn, make me a brilche. A brüüüüüüche!” You never knew what they said. Three words and you were on the floor because their breath would wither your face. There was no surviving rabbi breath. God knows what they ate—garlic and young Jewish boys. Terrible!

PLAYBOY: Did you go to the movies much?

BROOKS: Are you kidding? The dumps would open at ten o’clock Saturday morning and I’d be there. We’d get in for 11 cents, loaded down with Baby Ruths and O’Henrys and Mars bars. No Raisinets in those days. Sherreee! Bring Raisinets! PLAYBOY is looking a little peaked! No? Goy bastard! No offense. So, anyway, in the movies, even before the lights went out, paper clips would start to slingshot all over the place. You’d get a shot in the back of your head—it would lodge in your brain—and you’d hear them hitting the screen like rain through the whole movie. Then about 11 o’clock at night, there’d be a light in my eye. An usher would be slapping me awake and a Jewish woman screaming behind him, “Melvin! You have to eat!”

PLAYBOY: What was your favorite movie?

BROOKS: Horror movies. Frankenstein gave me nightmares. I’d be sleeping on the fire escape in the summer and the monster would climb up to get me. And just when he’d put his hand on my face and I couldn’t breathe, I’d see the gleam of that metal rod in his neck and I’d wake up screaming “Frankensteiiiiiiiin!” I’d yell. Scare everybody in the house. I’m still yelling it. Don’t tell anybody, but I watch Young Frankenstein from behind my fingers. (Phone rings) I’ve got it, Sherry. Hello? Cleavon Little! The talented black star of Blazing Saddles! I love your face! Your obedient Jew here. How are you? What can I do for you? … You’re looking for a part that will make you a millionaire? I’ve got it! Play Blanche du Bois. Right, in A Streetcar Named Desire. You’d be the first black guy ever to play Blanche. Tennessee would love it. But do it right. Go to Denmark, have the operation. You could open in Mobile, Alabama, to sensational reviews. Police dogs. Sirens. With a little luck, you could become the first transsexual martyr! … Yes, Cleavon, yes! Don’t be strange! I love your feet! (Hangs up) Speak, PLAYBOY.

PLAYBOY: When did you find out that you could be funny?

BROOKS: I was always funny. But the first time I remember was at Sussex Camp for Underprivileged Children. I was seven years old and whatever the counselors said, I would turn it around. “Put your plates in the garbage and stack the scraps, boys!” “Stay at the shallow end of the pool until you learn to drown!” “Who said that? Kaminsky? Grab him! Hold him!” Slap! But the other kids liked it and I was a success. I needed a success. I was short. I was scrawny. I was the last one they picked to be on the team. “Oh, all right, we’ll take him. Put him in the outfield.” Now, I wasn’t a bad athlete, but the other kids were champs. In poor Jewish neighborhoods, every kid could hit a mile. They could be on their back and throw a guy out at first. They were great and I was just good. But I was brighter than most kids my age, so I hung around with guys two years older. Why should they let this puny kid hang out with them? I gave them a reason. I became their jester. Also, they were afraid of my tongue. I had it sharpened and I’d stick it in their eye. I read a little more than they did, so I could say, “Touch me not, leper!” “Hey! Mel called me a leopard!” “Schmuck! Leper!” Words were my equalizer.

PLAYBOY: Where did you hang around? In the schoolyard?

BROOKS: Are you kidding? We couldn’t wait to get away from school. We hung out in the street—and on the corner. I mean, we didn’t hang out there just because the street came to a corner. We weren’t driven sexually crazy by a building coming to a point. We met there because there was a drugstore or a candy store on the corner. We’d all stand out on the sidewalk in warm weather and duel verbally, tell jokes, laugh it up. Girl watching was part of it, and so was having an egg cream. But the main thing was corner shtick, we called it, and in our gang, I was the undisputed champ at corner shtick.

PLAYBOY: Would you give us a sample?

BROOKS: The corner was tough. You had to score on the corner—no bullshit routines, no slick laminated crap. It had to be, “Lemme tell ya what happened today….” And you really had to be good on your feet. “Fat Hymie was hanging from the fire escape. His mother came by. ‘Hymie!’ she screamed. He fell two stories and broke his head.” Real stories of tragedy we screamed at. The story had to be real and it had to be funny. Somebody getting hurt was wonderful. “You hear what happened with Millie and the Buick?” “What? What?” “He was doing an eagle turn on his skates….” “Yeah? Yeah?” “Oogah! Oogah! Miltie thought it was applause, didn’t bother to look. Bam! Buick got him right in the ass. Did a somersault. Crunncchh! Out like a light, took him away, Saint Catherine’s Hospital. The nuns are with him now.” The nuns are with this little Jewish kid, right? And then you visit Miltie, propped up on pillows, very cool. “Who are these penguins?” he says. “And why do they want me to pee all the time?”

PLAYBOY: We’ve heard that medicine is kind of a hobby with you. How did you get interested in it?

BROOKS: I always thought it was great to be able to make people feel better. It was a little like being God. So I started to take charge when anybody got hurt playing ball. “Get the Mercurochrome. Put a Band-Aid on. Quick! Flappy fainted. Bring an egg cream!”

PLAYBOY: An egg cream has healing properties?

BROOKS: An egg cream can do anything. An egg cream to a Brooklyn Jew is like water to an Arab. A Jew will kill for an egg cream. It’s the Jewish malmsey.

PLAYBOY: But there’s no egg in an egg cream.

BROOKS: That’s the best part. That’s the wonder and the mystery of it. Talmudic sages for generations have pondered this profound question. Why is there no egg in an egg cream? Well, 1,000 years ago there may have been egg in egg creams. Joe Heller is very bright and he thought so. But Georgie Mandel and Speed Vogel are bright, too, and they applauded Julie Green’s reasoning. He said, “Egg creams are called egg creams because the top of a well-made egg cream looks like whipped egg white.” I can’t offer you an egg cream right now, but how about a Raisinet? If you scrape the chocolate off 5,000 of them, you could have an egg cream.

PLAYBOY: What does an egg cream do for you?

BROOKS: Physically, it contributes mildly to your high blood sugar. Psychologically, it is the opposite of circumcision. It pleasurably reaffirms your Jewishness. But what is all this with egg creams? Isn’t this a Playboy Interview? When are you going to ask me about sex?

PLAYBOY: Mr. Brooks, what is your attitude toward sex?

BROOKS: How dare you ask me such a filthy question” What do you take me far—an animal? Kindly change the subject!

PLAYBOY: Were there any Jewish princesses in Brooklyn in those days?

BROOKS: Sheila Rabinowitz. Jewish princesses are a second-generation thing. First-generation girls were scrubbing floors and helping out. Second-generation parents could afford to support royalty. But Sheila’s father was a coriander importer; he made it big in coriander; so Shelia was a first-generation Jewish princess. She lived two blocks away from school and she took a cab. She had four chain bracelets with different names on them, two on her wrists and two on her ankles. And all the names were gentile, just to put you in your place: Bob, Dick, Peter and Steve. They happened to be Jewish guys, but the names were gentile. Sheila came to class in a Pucci, and Pucci wasn’t even in business yet. Sixteen years old and she wore a turban with a rhinestone in the middle of it. And the accent! “Why, helloooo, theahhh. How aahh you?” What the hell is coriander, anyway?

PLAYBOY: What became of Sheila?

BROOKS: Don’t know. She was dreaming of the great world beyond the ghetto. I was happy where I was. When I was a kid, I was very confused by what the Jew was in the outer world. I knew what he was in Williamsburg. He was a runner and a rat and scared as hell. But Jews in the outside world I heard different, conflicting things about. First of all, I heard that they were the Communists, overthrowing all the governments in the world. When I was in high school, I thought a Jew’s job in life was to throw over every government. The other thing I heard was that the Jews were capitalists and had all the gold and the banks and that the Jews’ job was to kill all the socialists and the radicals. So I never really figured out what the Jewish mission was. Should I kill the capitalists and take their money? No, I’d be killing Jews. Should I stamp out the radicals so that we could keep our money? No, I’d be killing Jews. Very confusing. BUT (leaps to his feet) ENOUGH OF JEWS! I WILL SPEAK NO MORE OF JEWS! IN FACT, I WILL SPEAK NO MORE OF ANYTHING! (Ripping off several strips of Scotch tape, he seals his lips tight and then, in a frenzy, rolling his eyes and squealing wordlessly, slaps sticky ribbons of tape over his ears, over his nostrils, over his hair and finally, eyelids stuck shut, goes staggering around the room, dragging one leg, gurgling and mumbling) Look! Look wha’ th’ G’rm’ns did t’ me! (He tears off the tape) They stole into my foxhole at night and covered my face with Scotch tape.

PLAYBOY: In your movies, you make fun of Germans. Don’t you like them?

BROOKS: Me? Not like Germans? Why should I not like Germans? Just because they’re arrogant and have fat necks and do anything they’re told so long as it’s cruel, and killed millions of Jews in concentration camps and made soap out of their bodies and lamp shades out of their skins? Is that any reason to hate their fucking guts?

PLAYBOY: Certainly not. Have you ever been in Germany?

BROOKS: Only to kill Germans. I was in the Army, World War Two. Seventeen, I enlisted. Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Basic training, right? Make a soldier out of the Jew boy. Left, right. I tried to explain to the sergeant, walking is not good for Jews. He felt otherwise. Then one day they put us all in trucks, drove us to the railroad station, put us in a locked train with the windows blacked out. We get off the train, we get on a boat. We get off the boat, we get into trucks. We get out of the trucks, we start walking. Suddenly, all around us, Waauhwaauhwaauh! Sirens! Tiger tanks! We’re surrounded by Germans. It’s the Battle of the Bulge! Hands up! “Wait!” I say. “We just left Oklahoma! We’re Americans! We’re supposed to win!” Very scary, but we escaped.

I spent a lot of time in the artillery. Too noisy. Could not take the noise. All through the war, two cigarette butts stuck in my ears. Couldn’t read, couldn’t think, couldn’t even make a phone call. Bagharrroooooommmmm! Brrllaggghhaarrooooooooooommmmm! And they they started shooting. “Incoming mail!” Bullshit. Only Burt Lancaster says that. We said, “Oh, God! Oh, Christ!” Who knows, he might help. He was Jewish, too. “MOTHER!”

PLAYBOY: What did you do when you got out of the Army?

BROOKS: Wait! You’re going too fast! At the end of the war, I did Army shows. First for the Germans, then at Fort Dix I did some camp shows. We all rolled up our pants and were the Andrews Sisters. One of us is still doing LaVerne in the East Village. Anyway, after I got out, I had three choices. I could go to college and hang out a shingle and make $10,000 a year. Another thing for a Jew to do would be to become a salesman. Hipsy, pipsy, lotsa pep, you know? White-on-white shirt, black-mo-hair suit, Swank cuff links, and, if you made it, a cat-eye ring on the pinkie. And on the other pinkie, your bar mitzvah ring. That was the big Brooklyn jewelry artillery. Shine in everybody’s eyes at a party.

PLAYBOY: And the third thing?

BROOKS: Show business. But you got to understand something: Jews don’t do comedy in winter. In summer, all right. You’re a kid, you work in the mountains. That’s how I got started years before—as a pool tumeler. A pool tumeler is a busboy with tinsel in his blood. For eight bucks a week and all you can eat, you do dishes, rent out rowboats, clean up the tennis courts and, if you beg hard enough, they let you try to be funny around the pool. I’m 14 years old and I walk out on the diving board wearing a black derby and a big black-alpaca overcoat. I’m carrying two suitcases filled with rocks. “Business is terrible!” I yell. “I can’t go on!” And I jump in the pool. Big laugh—the Jews love it. But I don’t laugh—because the suitcases weigh a ton and like a shot I go to the bottom. The overcoat soaks up 20 gallons of water instantly. I run out of air, but I can’t lift the suitcases—and I can’t leave them in the water. They’re made of cardboard, in two minutes they’ll dissolve, and I need them for tomorrow’s act. God bless Oliver, that big goy! He was the lifeguard—Jews don’t swim, remember?—and every day he’d do a little swan dive and haul me up.

PLAYBOY: What happened after pool tumeling?

BROOKS: I joined a Borscht Belt stock company. They let me play the district attorney in Uncle Harry, a straight melodrama. I’m 14 and a half, but I’m playing a 75-year-old man. My only line was, I pour some water from a carafe into a glass and say, “Here, Harry, have some water and calm down.” But on opening night, I’m a little nervous, right? So I dropped the carafe on the table and it smashed and this flood rushed in all directions and made a waterfall off the table and all over the stage—such a mess! The audience gasped. I don’t waste a minute; I walk right down to the footlights and take off my gray toupee and say, “I’m 14, what do you want?” Well, I got a 51-minute laugh, but the director of the play came running down the aisle and chased me through five Jewish resorts.

PLAYBOY: So how did you become a comedian?

BROOKS: I became a drummer, that’s how. When we moved to Brighton Beach, I was 13 and a half and only a few houses away lived the one and only Buddy Rich. Buddy was just beginning with Artie Shaw then, and once in a while he would give me and my friend Billy half a lesson. When I went back to the mountains after the war, I played drums and sang. (Eyes suddenly dreamy, begins to patter rhythmically on his desk with fingertips as he sings) “It’s not the pale moooon that excites me, that thrills and delights me. Oh, nooooo….” Oh, I was so shitty. You’ve no idea.

Anyway, one time in the mountains I was playing drums behind a standard mountain comedian. Wonderful delivery, but all the usual jokes. “I just flew in from Chicago and, boy, are my arms tired.” “Was that girl skinny—when I took her to a restaurant, the waiter said, ‘Check your umbrella?’” Anyway, one night the comic got sick and they asked me to go on for him. Wow! But I didn’t want to do those ancient jokes, so I decided to go out there and make up stuff. I figured, I’ll just talk about things we all know and see if they turn out funny. Now, that day a chambermaid named Molly got shut in a closet and the whole hotel had heard her screaming, “Los mir arois!” Let me out! So when I went on stage, I stood there with my knees knocking and said, “Good evening, ladies and gentlemen … LOS MIR AROIS!” They tore the house down.

PLAYBOY: You continued to improvise your act, night after night?

BROOKS: Crazy, huh? But I did. Look, I had to take chances or it wasn’t fun being funny. And you know, there was a lot of great material lying around in the Catskills, waiting to be noticed. Like Pincus Cantor. He was the manager where I was working, an old-fashioned Jew from the Polish shtetl. He couldn’t handle the loudspeaker system at the hotel. Technology was beyond him. He was never sure if he had the speaker off or on and he usually had it on at the wrong time. It’s a peaceful sunny day in the mountains, right? People are snoozing in deck chairs, people are rowing slowly across the lake. Suddenly, a tremendous shout booms out. For ten miles in the mountains, you could hear it: “SON OF BITCH BASTARD! FILT’Y ROTTEN! HOW DEY CAN LEAVE A SHEET SO FILT’Y! THAT SON OF BITCH! LAT HIM SLEEP IN IT! I VUDN’T….IT’S VAAAAT? IT’S ON? OYYYYY!” Click.

So I did Pincus Cantor onstage—big hit. But I wasn’t a big hit, not at first. The Jews in the tearoom, the Jewish ladies with blue hair, would call me over and say, “Melvin, we enjoyed certain parts of your show, but a trade would be better for you. Anything with your hands would be good. Aviation mechanics are very well paid.” I’d walk by a bald guy, Sol Yasowitz. “Well, what did you think, Mr. Yasowitz?” I’d ask him. “Stunk.” With a little smile. You could never get a kind word out of the Jews. And you know, maybe I was terrible. I had this theme song, wrote it myself (Does a Donald O’Connor walk-on as he sings) “Dadadadat dat daaaa! Here I am/I’m Melvin Brooks!/I’ve come to stop the show./Just a ham who’s minus looks/But in your hearts I’ll grow!/I’ll tell you gags, I’ll sing you songs/Just happy little snappy songs that roll along/Out of my mind/ Won’t you be kind?/And please … love … Melvin Broooooooks!” Terrible, right? After that, you surely need a Raisinet, right? Wrong. But think it over. Believe me, there are very few things that work as well when covered with chocolate. Anyway, I wanted to entertain so badly that I kept at it until I was good. I just browbeat my way into show business.

PLAYBOY: Is it true that everybody hated you on Your Show of Shows?

BROOKS: Everybody hated everybody. We robbed from the rich and kept everything. There was tremendous hostility in the air. A highly charged situation, but very good. We were all spoiled brats competing with each other for the king’s favor, and we all wanted to come up with the funniest joke. I would be damned if anybody would write anything funnier than I would and everybody else felt the same way. There were seven comedy writers in that room, seven brilliant comedic brains. There was Mel Tolkin and Lucille Kallen. Then I came in. And spoiled everything. Then Joe Stein, who later wrote Fiddler on the Roof, and Larry Gelbart, who writes and produces M*A*S*H. Mike Stewart typed for us. Imagine! Our typist later wrote Bye Bye Birdie and Hello, Dolly! Later on, Mike was replaced at the typewriter by somebody named Woody Allen. Neil and Danny Simon were there, too, but Doc was so quiet we didn’t know how good he was. Seven rats in a cage. The pitch sessions were lethal. In that room, you had to fight to stay alive.

PLAYBOY: From what we’ve heard, your competitive relationship with the other writers was nothing compared with your troubles with Max Liebman, the producer of the show.

BROOKS: Max hated me. I was a pretty snotty kid. But I hated him right back. When Sid first asked Max to hire me, Max wouldn’t do it. So Sid gave me $50 a week himself and I’d wait in the hallway outside where Sid and Max and Mel and Lucille were writing the show. After a while, Sid would stick his head out and say, “We need three jokes.” So I’d give him three jokes, but Max wouldn’t let me in.

PLAYBOY: What didn’t he like about you?

BROOKS: He didn’t like my fast mouth. When I’d sass him back, he’d throw a lighted cigar at me—right at my face! I’d duck. One day, we were standing on the stage. I yelled, “Pepper Martin sliding into second! Watch your ass!” And I ran straight at him at full speed and then threw myself into a headfirst slide. Slid right between his legs, sent him flying in the air, scared the shit out of him. We laugh about it now, but it was rough then. He’s a great showman, though; unconsciously, I think I still copy him.

PLAYBOY: Didn’t you once scare the shit out of General Sarnoff?

BROOKS: True! One day they had a big conference in the RCA Building. All the big shots. General Sarnoff, the chairman of the board of RCA; Pat Weaver, the president of NBC; Max Liebman and Sid. When I tried to walk into the room with them, the door was slammed in my face. But I wanted to know what they were planning. Would there be a new show? Should I buy a new car? So I put on a white duster and a straw hat and I crashed through the door into the meeting and jumped up on the conference table. “Hurray!” I yelled. “Hurray! Lindy has landed at Le Bourget!” This was 1950. And I whipped off my straw hat and skimmed it across the room and it sailed right out the window and has never been seen since. Then I burst into the Marseillaise while General Sarnoff clutched his heart and Liebman picked his eyes up off the floor. Weaver was white as a sheet. Sid was the only one who laughed; staggered around, holding his gut. Liebman said, “And now, if you will kindly leave us, Mr. Brooks!” But I said, “Don’t you understand? Lindy made it!”

PLAYBOY: So much for your offscreen material. What did you write for the show?

BROOKS: Masterpieces. Best work I ever did. We did eight comedy items a week. Live. No taping. Big classy items.

PLAYBOY: Would you run through a skit?

BROOKS: I remember the first one I wrote for Sid. Jungle Boy. “Ladies and gentlemen, now for the news. Our roving correspondent has just discovered a jungle boy, raised by lions in Africa, walking the streets of New York City.” Sid played this in a lionskin, right? “Sir, how do you survive in New York City?” “Survive?” “What do you eat?” “Pigeon.” “Don’t the pigeons object?” “Only for a minute.” “What are you afraid of more than anything?” “Buick.” “You’re afraid of a Buick?” “Yes. Buick can win in death struggle. Must sneak up on parked Buick, punch grille hard. Buick die.”

PLAYBOY: Who were the show’s other stars?

BROOKS: Imogene Coca, brilliant lady. Carl Reiner, greatest straight man in the world. And Howie Morris! Howie had the best nose ever given to a Jew. No job. His own nose. A miracle! On the nose alone he could pass. Also a genius. Didn’t know a word except in English but could speak any language—German gibberish, Italian gibberish, Russian gibberish. Amazing ear for accents. You’d think it was the real thing. But the best thing about Howie was that he was the only guy on the show who was shorter than me! Gave me this incredible feeling of power.

So one night, just after he came on the show, we were walking along MacDougal Alley in the Village, chatting about the show, getting acquainted. Lovely evening, just getting dark. So I decided to rob him. No, really. I slapped him around, knocked him against a yellow Studebaker. “This is a stick-up!” I said. I had my hand in my coat pocket with my finger pointed like a pistol. “Gimme everything you got or I’ll kill ya!” My eyes were glittering. I looked crazy. He went white. I took his wallet, his watch, even his wedding ring. Cleaned him out. Then I ran away in the night. He staggered to a phone booth, called Sid. Sid said, “Oh, he’s started that again, has he? Whatever you do, don’t call him up or go to his house, he’ll kill ya.” Howie said, “But when do I get my stuff back?” Sid said, “Ya gotta wait till he comes to his senses.”

Well, for three weeks, Howie waited. No wallet, no watch. Had to buy another wedding ring. I’d say hello to him every morning like nothing had happened. “Hi, Howie. How ya doing? D’ya like the sketch?” He’d say, “Very good, Mel. Like it a lot.” Then he’d go to Sid and say, “When’s he going to remember? My license was in my wallet. I haven’t been able to drive for three weeks.” And Sid would say, “Wait.” And then one day I stared at Howie and hit my head. “Howie! Oh, my God! I robbed you, I’m so sorry! Here’s your wallet! Here’s your money! Here’s your ring!”

Well, it was the longest practical joke in history, because three years later—by now we’re the best of friends—we’re rowing on the lake in Central Park at lunchtime. Lovely sunny day. Butterflies making love, the splash of the oars. Howie is rowing. We go under a secluded bridge. Perfect place for a holdup. I stand up, put my hand in my pocket, slap him in the face. Howie’s smart. The prey always respects the predator’s prerogatives. So without a word, he forks over his wallet, his watch, his ring, takes off his shoes, ties them around his neck, jumps overboard—the water’s up to his chin—and wades ashore. Well, that time I gave him his stuff back in a few days. But I intend to rob him again someday, ladies and gentlemen, because robbing Howie is what I do best.

PLAYBOY: Over the years, what was your main contribution to the show?

BROOKS: Energy and insanity. I mean, I would take terrifying chances. I was totally willing to be an idiot. I would jump off into space, not knowing where I would land. I would run across tightropes, no net. If I fell, blood all over. Pain. Humiliation. In those pitch sessions, I had an audience of experts and they showed no mercy. But I had to go beyond. It wasn’t only competition to be funnier than they were. I had to get to the ultimate punch line, you know, the cosmic joke that all the other jokes came out of. I had to hit all the walls. I was immensely ambitious. It was like I was screaming at the universe to pay attention. Like I had to make God laugh.

Funny, I remember one year at the Emmy-awards ceremony, they gave the award for comedy writing to the writers of The Phil Silvers Show, and they had never ever given an Emmy to the writers of Your Show of Shows. So I jumped up on a table and started screaming, right there in front of the cameras and everybody. “Coleman Jacoby and Arnie Rosen won an Emmy and Mel Brooks didn’t! Nietzsche was right! There is no God! There is no God!”

PLAYBOY: You know, you’ve described a lot of really wild behavior. Are you sure some of it wasn’t actually a little crazy?

BROOKS: I’m sure it was. I went through some disastrous times when I was a young man. After I was hired by Your Show of Shows, I started having acute anxiety attacks. I used to vomit a lot between parked Plymouths in midtown Manhattan. Sometimes I’d get so anxiety-stricken I’d have to run, because I’d be generating too much adrenaline to do anything but run or scream. Ran for miles through the city streets. People stared. No joggers back then. Also, I couldn’t sleep at night and I’d get a lot of dizzy spells and I was nauseated for days.

PLAYBOY: What brought on all this anxiety?

BROOKS: Fear of heights. Look at what had happened. I was a poor kid from a poor neighborhood, average family income $35 a week. I felt lucky to be making $50 a week, which is what Sid was paying me. And then, on top of that, I got a screen credit! “Additional dialogue, Mel Brooks.” Wow! But when I was listed as a regular writer and my pay went to $250 a week, I began to get scared. Writer! I’m not a writer. Terrible penmanship. And when my salary went to $1,000 a week, I really panicked. Twenty-four years old and $1,000 a week? It was unreal. I figured any day now they’d find me out and fire me. It was like I was stealing and I was going to get caught. Then, the year after that, the money went to $2,500 and finally I was making $5,000 a show and going out of my mind. In fact, the psychological mess I was in began to cause a real physical debilitation. To wit: low blood sugar and underactive thyroid.

PLAYBOY: You—underactive thyroid?

BROOKS: Everybody thinks, Mel Brooks, that maniac! The energy of that man! He must be hyperthyroid. Au contraire, mon frère. To this day, I take a half grain of thyroid—and an occasional Raisinet. Now, seriously, have you got kids? How’s about taking a couple boxes Raisinets for the kids? They’ll love ‘em, and—

PLAYBOY: But chocolate is terrible for their teeth.

BROOKS: Are teeth so good for chocolate? Let’s be fair.

PLAYBOY: Thanks, but—

BROOKS: Take your time. It’s a big decision. Maybe you should call your lawyer. Use my phone, OK? Where were we?

PLAYBOY: What straightened you out emotionally?

BROOKS: Mel Tolkin sent me to an analyst. Strictly Freudian. On the couch—no peeking. But the man himself was kind and warm and bright. Most of my symptoms disappeared in the first year, and then we got into much deeper stuff—whether or not one should live and why.

PLAYBOY: Did you find any answers to that?

BROOKS: The main thing I remember from then is bouts of grief for no apparent reason. Deep melancholy, incredible grief where you’d think that somebody very close to me had died. You couldn’t grieve any more than I was grieving.

PLAYBOY: Why?

BROOKS: It was connected with accepting life as an adult, getting out in the real world. I was grieving about the death of childhood. I’d had such a happy childhood, my family close to me and loving me. Now I really had to accept the mantle of adulthood—and parenthood. No more cadging quarters from my older brothers or my mother. Now I was the basic support of the family unit. I was proud of doing my bit, but it meant no longer being the baby, the adorable one. It meant being a father figure. Deep, deep shock. But finally I went on to being a mature person.

You often hear, you know, that people go into show business to find the love they never had when they were children. Never believe it! Every comic and most of the actors I know had a childhood full of love. Then they grew up and found out that in the grown-up world, you don’t get all that love, you just get your share. So they went into show business to recapture the love they had known as children when they were the center of the universe.

PLAYBOY: Are you saying that analysis changed you from the wild man who did a Pepper Martin slide at Max Liebman into the mature man who wrote and directed Blazing Saddles?

BROOKS: I’m saying that you should stop trying to be funnier than the Jew. What changed me was success and having to solve the problems of success. At that time of life, no matter what you do, you’re getting your education, what Joseph Conrad called the bump on the head. I got mine from the analyst and from Mel Tolkin. Between them, they were the father I never had. Sherreeeeee! Bring me some Trident gum! I gave up smoking, folks, on January 3, 1974. In lieu of eating my desk, I chew gum. ‘Cause the mouth still wants to inhale. Already I’ve inhaled a Bell telephone; that’s how fierce the desire is.

PLAYBOY: Can you give some advice to someone who is trying to quit smoking?

BROOKS: Suck somebody else’s nose.

PLAYBOY: Thank you. Now about Tolkin….

BROOKS: Tolkin is a big, tall, skinny Jew with terribly worried eyes. He looks like a stork that dropped a baby and broke it and is coming to explain to the parents. Very sad, very funny, very widely read. When I met him, I had read nothing—nothing! He said, “Mel, you should read Tolstoy, Dostoievsky, Turgenev, Gogol.” He was big on the Russians. So I started with Tolstoy and I was overwhelmed. Tolstoy writes like an ocean, in huge, rolling waves, and it doesn’t look like it was processed through his thinking. It feels very natural. You don’t question whether Tolstoy’s right or wrong. His philosophy is housed in interrelating characters, so it’s not up for grabs. Dostoyevsky, on the other hand, you can dispute philosophical points with, but he’s good, too. The Brothers Karamazov ain’t chopped liver.

PLAYBOY: So you got rich, cultured, secure—then what happened?

BROOKS: And then the roof fell in. There I am, strolling around in silk shirts and thinking, I’m cut out for greatness. Television’s too small for me. How am I going to get out of this lousy racket? And suddenly I am out of it. The show is off the air. One day it’s $5,000 a week, the next day it’s zilch. I couldn’t get a job anywhere! Comedy shows went out of style and the next five years I averaged $85 a week. Five thousand a week to $85 a week! It was a terrifying nose dive.

PLAYBOY: What about the money you had saved?

BROOKS: What money? Are you kidding? I was married! I was so much in debt I couldn’t believe it! All I had was a limited edition of War and Peace and an iron skate key. I kissed the skate key four times a day just to have something to do.

PLAYBOY: How about the record? Didn’t you and Reiner record The 2000 Year Old Man not long after the show folded?

BROOKS: A year later, the record came out. Saved me. Sold maybe 1,000,000 copies. And we did two others, 2001 and the Cannes Film Festival. We’d been doing the act for nothing at parties. We’d go to Danny’s Hide-A-Way in New York and Carl would say, “Sir, I understand that you were living at the time of Christ.” I’d say, “Christ? Can’t place him. Thin, nervous fella? Yeah. Came in the store, never bought anything. Little beard, cute. Wore sandals, right?” We did it once at a big party at Carl’s house and Steve Allen said we ought to make a comedy record, there was money in it. “What? Money in it?” So we got a shipment of black Russian health bread—you know, the round, flat kind. Ripped the shit out of it trying to make grooves, but the reproduction is pretty good, don’t you think? And if you don’t like the jokes, you can put cream cheese on them and eat them. Anyway, it was a good thing the record took off. In the meantime, my marriage had fallen apart and alimony and child support were eating me up.

PLAYBOY: How did you meet Anne Bancroft?

BROOKS: Anne Bancroft? Never heard of her.

PLAYBOY: Famous actress, beauty of stage and screen, star of The Miracle Worker, Two for the Seesaw, The Pumpkin Eater, featured in the forthcoming film version of The Prisoner of Second A venue, married to some Jewish comedian.

BROOKS: Oh, that Anne Bancroft. Yes, I am a great fan of hers—and of her husband’s. When did I meet her? Let’s go back to February 5, 1961, four o’clock in the afternoon. I went to the rehearsal of a Perry Como special, and there she was, singing in a beautiful white gown. Strangely enough, she was singing Married I Can Always Get, and when she finished the song, I stood up and clapped loudly in this empty theater. “Bravo’“ I shouted. “Terrific!” Then I rushed down the aisle and up onto the stage. “Hi,” I said, “I’m Mel Brooks.” I was really a pushy kid. And I shook her hand and she smiled and laughed.

Anyway, she said she was going to the William Morris office to see her agent, so I said, “Oh, by chance I happen to be going there, too.” Big lie. “Let’s all take a cab together.” Vrrrrrreeeeeet! I gave this great New York whistle. It stopped a cab. Later she said that really impressed her. We went to her agent’s office. I said, “I haven’t seen The Miracle Worker yet, but I hear it’s great.” She said, “Want me to do it for you?” I said, “The whole play?” She said, “Yes.” She obviously liked me, too. Well, she did the whole play! A one-hour version right there in the office! The fight scene and everything. And then Waaaa! Waaaa! The screaming at the end, the buckets of water, she did everything. I was on the floor. I was in tears, screaming with laughter, stunned.

I called and called her that night. She wasn’t in. Next day I called her and went over with my record album and we sat for six hours in the living room and talked. That night she was going to Village Vanguard. I managed to be there. Then I went to a closing party for The Miracle Worker. Everybody was crazy about her. Me, too. I really loved her. I just fell in love. I hadn’t fallen in love since I was a schoolboy. She was just radiant and beautiful and when we talked, I saw how bright she was. And her humor!

I asked her about dates and she said that very few men asked her to go out. And I realized that a man had to be pretty sure of himself, because she was quite an illustrious person. Just normal males who wanted to be big shots, wanted to hold their own, they couldn’t deal with that. She was a very hard woman to dominate if you wanted to be Mr. Male. But I wasn’t interested in dominating.

So we started going out and I told her, “OK, you’re very bright. You’re going to be my foreign-movie date. We’ll go see foreign movies together.” We went to the Thalia because it was 99 cents, and to dozens of recording sessions. All I could get into for nothing was recording sessions. Sometimes we ate in Chinatown for a buck-twenty-five. We walked, we held hands. I saw her every day. She would cook a lot, to save money. Great cook. Eggplant parmigiana and lasagna, wonderful Italian dishes. After a while, we just didn’t see anybody else. Not because we said “Let’s go steady” but because nobody else was as fascinating as we were to each other. Finally, I got a couple of TV spectaculars, as they were called then. An Andy Williams show, a Jerry Lewis show. Then the record began to save my life. But it was Get Smart!, a TV series I did with Buck Henry, that made it possible for us to get married.

PLAYBOY: Was it tough to bring yourself to the point of asking?

BROOKS: I never did. We were staying out at Fire Island and my mother had come to visit us, and her parents, too, and we were staying in separate rooms but still living in the same house. Didn’t look nice for the parents. So suddenly Annie said, “Why don’t we get married? It’ll be so much easier for the folks to deal with our relationship.” And I said, “Oh, absolutely. Fine.” And she nearly fainted. Then she got scared. “Well, I don’t know if I want to do this—really get married.” She had been married before and it hadn’t been good.

Anyway, we got married in I964, on my lunch hour. It was a civil ceremony. Annie is Italian and I’m Jewish. We were married by a Presbyterian. There was a black kid waiting in the anteroom and I asked him if he would stand up for us. His name was Andrew Boone. He had no idea that it was Mel Brooks marrying Anne Bancroft, because her maiden name is Italiano and she was married under that name. I didn’t even have a wedding ring for her. Annie had an old earring. It was made of very thin, bendable silver, looked like a piece of wire. I just twisted that around and gave her that. The clerk was very upset about that; he liked regular rings. Afterward, I had to go back to work and that night I went to her apartment for our wedding dinner. Annie made me spaghetti. It was great. Just the two of us.

It’s been like that to this day. My wife is my best friend, and I can’t think of anybody I’d rather be with, chat with. We live way out here in California now, in a foreign place, so we need each other a little more. We’re even closer. We have plenty of fights; I mean we’re married, right? But for me, this is it.

PLAYBOY: Isn’t it about time we discussed sex?

BROOKS (rising indignantly): I beg your pardon. We hardly know each other, and besides, I’m already married. You were proposing? Anyway, I’m not in favor of miscegenation. Later for sex. Let’s keep that guy on the toilet turning the pages. I think I’d rahthah discuss AHT. Why don’t we talk about The Producers?

PLAYBOY: Your first movie, 1967. How did you get The Producers off the ground?

BROOKS: With 12,000 German slaves and lots of ropes. I had this idea about two schnooks on Broadway who set out to produce a flop and swindle the backers, and the flop was to be called Springtime for Hitler. I wrote the script in nine months, with the help of my secretary, Betty Olsen, and then couldn’t think of anybody to direct it. So it had to be me. But I hated the idea of directing, and after four pictures I hate it even more. Directing is a terrible, anxious process. It’s all collaboration, and if you have a dream, it’s diluted very quickly by the slightest ineptness in any of your collaborators. They’re supposed to help you, but too often they help you into your grave. Your vision can never achieve perfection. If you want to be a moviemaker, you’ve got to say, “All right, I’ll chop the dream down. I’ll be very happy if I get 60 percent of my vision on the screen.”

PLAYBOY: Why do you direct if you don’t like it?

BROOKS: In self-defense. Basically, I’m a writer. I’m the proprietor of the vision. I alone know what I eventually want to happen on the screen. So if you have a valuable idea, the only way to protect it is to direct it.

PLAYBOY: How did you get to direct The Producers?

BROOKS: I went to all the big studios with Sidney Glazier, my producer, and said, “I’m going to have to direct this.” They said, “Please get out of here before you get hurt.” There were physical threats. Finally, someone at Universal Pictures said, “You can direct, but it has to be called Springtime for Mussolini. Nazi movies are out.” I said, “I think you missed the point.” Then I met Joseph E. Levine, a plain person from the street. “You think you can direct it?” “Yes.” “OK.” Shook hands. That was it! In the middle of the night, I woke up in a cold sweat. “Foolish person! You had to open your big mouth.”

PLAYBOY: Still, you brought it in on schedule.

BROOKS: And under budget: $941,000. I won an Oscar for the Best Screenplay of 1968. And the picture died at the box office. Anyway, that’s what Aveo-Embassy said. Their motto is emblazoned in Hebrew letters on the office wall. WE MAKE THE MONEY, YOU TRY AND FIND IT.

PLAYBOY: But The Producers was a critical success, wasn’t it?

BROOKS: Never believe it. Today everybody calls The Producers a classic. But at the time, you never saw such vitriolic reviews. What can I tell you? Some critics are emotionally desiccated, personally about as attractive as a year-old peach in a single girl’s refrigerator. It’s easy to say shit is shit, and it should be said. But the real function of a critic is to see what is truly good and go bananas when he sees it.

PLAYBOY: With your first picture a financial flop, how did you finance The Twelve Chairs?

BROOKS: Minimally. I got $50,000 for writing and coproducing the picture and it took three years to make. After the tax bite, I got about half of the $50,000, so that means I was living on $8,000 a year and the good nature of several banks. We shot the picture in Yugoslavia, which saved us a lot of money but gave us a lot of headaches. When I went to Yugoslavia, my hair was black. When I came back, nine months later, it was gray. Truly. To begin with, it’s a very long flight to Yugoslavia and you land in a field of full-grown corn. They figure it cushions the landing. The first thing they tell you is that the water is death. The only safe thing to drink is Kieselavoda, which is a mild laxative. In nine months, I lost 71 pounds. Now, at night, you can’t do anything, because all of Belgrade is lit by a ten-watt bulb, and you can’t go anywhere, because Tito has the car. It was a beauty, a green ’38 Dodge. And the food in Yugoslavia is either very good or very bad. One day we arrived on location late and starving and they served us fried chains. When we got to our hotel rooms, mosquitoes as big as George Foreman were waiting for us. They were sitting in armchairs with their legs crossed.

The Yugoslav crew was very nice and helpful, but you had to be careful. One day in a fit of pique, I hurled my director’s chair into the Adriatic. Suddenly I heard “Halugchik! Kakdivmyechisnybogdanblostrov!” On all sides, angry voices were heard and clenched fists were raised. “The vorkers,” I was informed, “have announced to strike!” “But why?” “You have destroyed the People’s chair!” “But it’s mine! It says Mel Brooks on it!” “In Yugoslavia, everything is property of People.” So we had a meeting, poured a lot of vodka, got drunk, started to cry and sing and kiss each other. Wonderful people! If they had another ten-watt bulb, I’d go there to live.

PLAYBOY: What happened when Twelve Chairs was released?

BROOKS: The movie was released at Meyer Roberts’ apartment in Evanston, Illinois. Sixteen people attended the world premiere. Meyer himself couldn’t make it; he had a date. We were all fingerprinted and booked by the police. No, the picture did pretty well in New York, but it couldn’t get across the George Washington Bridge. Taught me something. There is no room in the business now for a special little picture. You either hit ’em over the head or stay home with the canary.

PLAYBOY: And Blazing Saddles was designed to hit ‘em over the head.

BROOKS: No. Actually, it was designed as an esoteric little picture. We wrote it for two weirdos in the balcony. For radicals, film nuts, guys who draw on the washroom wall—my kind of people. I had no idea middle America would see it. What would a guy who talks about white bread, white Ford station wagons and vanilla milk shakes on Friday night see in that meshugaas?

PLAYBOY: How did you hit on the idea for Blazing Saddles?

BROOKS: It’s an interesting story; I don’t think I’ll tell it. Can I interest you in a Raisinet? No? Maybe you’d like a chocolate-covered Volkswagen? Do you have a dollar on you? I hate to answer questions for nothing. (Accepts a dollar) Thank you. For two more I’ll sell you my T-shirt. See this little alligator on the pocket? I understand that in the Everglades, there are alligators with little Jews on their shirt pockets.

We were talking about Blazing Saddles. It was Andy Bergman’s idea. He sent Warner Bros. a rough draft of a screenplay called Tex-X. What grabbed me were the possibilities of a modern black man arriving in the traditional West. Like, he’d say, “Right on, baby!” And they’d say, “Consarnit!” Then I realized that at the same time I could make fun of Westerns and the West. So I called Bergman and said, “Do you mind if I despoil your script?” And he said, “Can I help ?” David Brown at Warner’s called me and I told him I wanted to write it the way we wrote Your Show of Shows—lock a bunch of weirdos up together and come out with a great script. We called in Norman Steinberg and Alan Uger, a Jewish comedy team, and Richard Pryor, a black person of outré imagination. Then we turned on the tape recorder and started bullshitting. Pryor wrote the Jewish jokes, the Jews wrote the black jokes. Nine months later, we had a finished script.

Blazing Saddles was a breakthrough comedy. It carried the audience into territory that film comedy had never entered before-kinds of satire, kinds of special vulgarity-and some critics felt confused and disoriented. So they thought that because they were confused, we were confused. We weren’t.

PLAYBOY: What was the point of the vulgarity—the farting scene, for example?

BROOKS: The farts were the point of the farting scene. In real life, people fart, right? In the movies, people don’t. Why not? When I was in high school, I knew a kid, won’t mention his name—Robert Weinstein—who when he let one go, you could get in it and drive it away, that’s how firm. But before Blazing Saddles, America had not come to terms with the fart. Wind was never broken across the prairie in a Ken Maynard picture. In every cowboy picture, the cowboys sit around the campfire and eat 140,000 beans, and you never hear a burp, let alone a bloozer.

PLAYBOY: Oh. Was anything cut out in the interest of good taste?

BROOKS: Yes. A scene between Cleavon Little, the black sheriff, and Madeline Kahn. The scene takes place in the dark. “Is it twue vot zey say,” Madeline asks him seductively, “about how you people are built?” Then you hear a zipper. Then you hear her say, “Oh! It’s twue! It’s twue! It’s twue!” That much is in the picture. But then comes the line we cut. Cleavon says, “Excuse me, ma’am. I hate to disillusion you, but you’re sucking my arm.”

PLAYBOY: What happened to your life and your career after Blazing Saddles?

BROOKS: I became John Carradine. Aquiline nose, face long and aristocratic, voice deep and vibrant. Thinking of running for the U.S. Senate….Frankly, I’m in demand and it’s great. I can take my best shot and take it under the best conditions. I have a three-picture deal at Fox that gives me everything I want.

PLAYBOY: Which brings us to Young Frankenstein. But first, a little bone to pick. Why, why do you always have so little sex in your movies?

BROOKS: What? Who? Avoid sex? Oh, that word! To whom are you speaking, sir? My name is Kaminsky.

PLAYBOY: In The Producers, for example, the closest thing you had to sex was a Swedish secretary with big boobs.

BROOKS: Ya gotta admit that’s pretty close.

PLAYBOY: And looking at Twelve Chairs, you’d think the Soviet Union was populated by 250,000 people without glands. Even in Blazing Saddles, which is obviously intended as a comic saturnalia, there are plenty of anal jokes but hardly any genital jokes.

BROOKS: What about Lili von Shtupp? We almost called the picture She Shtupps to Conquer.

PLAYBOY: German sex is the best you can do? Mr. Brooks, some people say your humor is prepubescent. What do you say to that?

BROOKS: I say, if I may quote a comedy writer named Joe Schrank, I can hardly believe my hearing aid. I say in a couple hundred years cabs will be so low to the ground you’ll have to step over them and get in from the other side.

PLAYBOY: We say let’s talk about Young Frankenstein.

BROOKS: I’ve got a better idea. I’m surprised you haven’t asked me. Let’s talk about sex! Are you ready out there, all you goys? Lock the bathroom door! The Jew is going to talk dirty! Speaking of pornographic movies, the trouble with them is, you’re watching them do all these wild things on the screen, six girls with big tits and a guy with a schwanstucker like the Chrysler Building, and you get all hot and bothered, but you can’t do anything about it. I’d like to see a porno flick if I could do something about it. Like, if there was an intermission at dirty movies, so you could go get your Goobers—or Raisinets, for that matter. Tell me, have you ever considered the possibilities of a Raisinet as a sex object?

PLAYBOY: Did your mother ever discuss sex with you boys?

BROOKS: Never. Completely taboo. There was no sex. Children arrived because of affection. You had a terrific bout of affection with each other and suddenly there in the kitchen was a baby at the table, eating. Wonderful! A miracle! I really believed that until Morris Steinberg told me in seven B. His nose is not the same, because I gave it a punch and said, “Not my mother! No, sir!” It was a tough thing to hear. But once I knew the score, I got busy.

Most sex in Brooklyn was in the back of a Buick; a Ford was too small to move around in. And most sex was petting. A lot of hallway jobs. Banging against each other in those hallways was terrible and you gotta watch hitting the bells, because you’d get the whole tenement shouting down the stairs at you. So we sneaked up to the roof. My first affair was on the roof of 365 South Third Street. And there was a guy flying pigeons who we saw later watching us. It was late at night, but I heard—ha-ha-ha—a little laughing. Very embarrassing. But there wasn’t very much sex for teenagers. We were shy and it was taboo. You got married and had sex.

PLAYBOY: Was there anything kinky going on in those days?

BROOKS: Not that I knew or heard of. Nothing hip or weird or sensational like today. It was thrilling because we were very young, but it was very straight. I mean, no two guys and a girl, none of that.

PLAYBOY: What about Jewish girls—are they puritanical?

BROOKS: The best thing about Jewish girls is, they can tell real jade. No, I don’t go for those jokes about “What do you mean, she’s dead? I thought she was Jewish!” Jewish women are very exciting, as exciting sexually as any other group. Even so, my advice to a young man marrying a Jewish girl would be to have three and a half years of foreplay. Of course, most girls in every group are reserved about getting down to it. They don’t usually do it right away. But once they do it, women are bananas. They don’t wanna do it, you can’t make them do it, there’s no way they’ll do it—but once they do it, they don’t let you alone. Then it’s “OK, Murray, let’s do it till we die!”

But PLAYBOY readers, I think, are different. I think they’re either single or have single dreams. Singles bars, single girls. They have sultan fantasies, 26 chicks coming at them, screaming and biting them. In real life, I mean, you’re lucky if your wife will do it with you.

PLAYBOY: What about orgies?

BROOKS: No, I’m Jewish. Besides, at orgies there are too many people. You’re naked and you hardly know each other. “Are you Mel Brooks?” “Yes.” “I loved Springtime for Hitler.” “Thank you.” “Did you write the lyrics as well as the music?” Who cares? And orgies would be embarrassing. You meet somebody later that you’ve seen at an orgy; you don’t want that. Maybe in Romania you’d never see anybody again. But think of the plane fare.

PLAYBOY: What about sexual apparatus—such as vibrators and dildos and electrical—

BROOKS: Please, you’re talking to a Jewish person. Electrical apparatus would scare me. God gave us enough apparatus to get the thing done. I understand in Japan, though, they make rubber people you can go to bed with. A whole rubber person, supposed to be sensational. Costs as much as a Toyota, but you can’t back up in it. OK? Enough sex? Would you like me to expose myself, Mr. Filth?

PLAYBOY: Thank you, no. But there is one side of sex we haven’t discussed. Your pictures all have happy endings, but you may have noticed that boy never gets girl.

BROOKS: True. At the end of the first three pictures, boy gets boy. Zero Mostel gets Gene Wilder, Frank Langella gets Ron Moody, Gene Wilder gets Cleavon Little. It’s a remarkable coincidence, and I’m not sure what it means. But I’m pretty sure my need to have my male characters come together and be close is not some sort of a sexual need I’ve displaced into these people. I think it goes back a lot further than sex. All the way back to my father, whom I never really knew and can’t remember. I can’t tell you what sadness, what pain it is to me never to have known my own father, who died when I was two and a half. All I know is what they’ve told me. He was lively, peppy, sang well. Isn’t it sad that that’s all a son should know about his father? If only I could look at him, touch his face, see if he had eyebrows! Maybe in having the male characters in my movies find each other, I’m expressing the longing I feel to find my father and be close to him.

PLAYBOY: But in Young Frankenstein, even the monster gets a girl.

BROOKS: Yes. I’m turning straight. In fact, there’s a lot of heterosex in Young Frankenstein. There’s lust on a lab table, rape in a cave and a big double-wedding-night sequence. But sex isn’t the point. What we had in mind was a picture that played on two main levels. One, we wanted to make a hilarious pastiche of the old black-and-white horror films of the Thirties. Two, we wanted to offer sincere and reverent homage to those same beautifully made movies.

PLAYBOY: What’s the difference between directing comedy and directing a serious picture?

BROOKS: I’ll tell you that after I call Sherry. Sherreeee! Take a letter, please, to this guy who calls Blazing Saddles “an artless and vulgar display” and says he and his wife saw it only because they were “unwary tagalongs.” “Dear Sir: Blazing Saddles has been rated R. The R is there to protect people like you and your wife from unwittingly attending adult movie fare. I don’t think it’s fair of you to walk into an R-rated film and then criticize it for containing sophisticated material. I also don’t think that the excuse of tagging along relieves anyone of culpability. One doesn’t wander into a brothel and then attack the establishment for not being Howard Johnson’s. Sincerely yours, Mel Brooks.” Where were we?

PLAYBOY: Directing comedy.

BROOKS: There’s one thing you’ve got to understand before you can direct comedy. Comedy is serious—deadly serious. Never, never try to be funny! The actors must be serious. Only the situation must be absurd. Funny is in the writing, not in the performing. If the situation isn’t absurd, no amount of hoke will help. And another thing, the more serious the situation, the funnier the comedy can be. The greatest comedy plays against the greatest tragedy. Comedy is a red rubber ball and if you throw it against a soft, funny wall, it will not come back. But if you throw it against the hard wall of ultimate reality, it will bounce back and be very lively. Vershteh, goy bastard? No offense. Very, very few people understand this.

PLAYBOY: Does Woody Allen understand it?

BROOKS: Woody Allen is a genius. His films are wonderful. I liked Sleeper very, very much. It’s Woody’s best work to date. The most imaginative and the best performed. I was on the floor, and very few people can put me on the floor. He’s poetic, but he’s also a critic. He artfully steps back from a social setting and criticizes it without—I suspect—without letting himself be vulnerable to it.

PLAYBOY: And you?

BROOKS: I’m not a critic. I like to hop right in the middle, right into the vortex. I can’t just zing a few arrows at life as it thunders by! I have to be down on the ground and shouting at it, grabbing it by the horns, biting it! Look, I really don’t want to wax philosophic, but I will say that if you’re alive, you got to flap your arms and legs, you got to jump around a lot, you got to make a lot of noise, because life is the very opposite of death. And therefore, as I see it, if you’re quiet, you’re not living. I mean you’re just slowly drifting into death. So you’ve got to be noisy, or at least your thoughts should be noisy and colorful and lively. My liveliness is based on an incredible fear of death. In order to keep death at bay, I do a lot of “Yah! Yah! Yah!” And death says, “All right. He’s too noisy and busy. I’ll wait for someone who’s sitting quietly, half asleep. I’ll nail him. Why should I bother with this guy? I’ll have a lot of trouble getting him out the door.” There’s a little door they gotta get you through. “This will be a fight,” death says. “I ain’t got time.”

Most people are afraid of death, but I really hate it! My humor is a scream and a protest against goodbye. Why do we have to die? As a kid, you get nice little white shoes with white laces and a velvet suit with short pants and a nice collar, and you go to college, you meet a nice girl and get married, work a few years—and then you have to die? What is that shit? They never wrote that in the contract. So you yell against it, and if you yell seriously, you can be a serious playwright and everybody can say. “Very nice.” But I suspect you can launch a little better artillery against death with humor.

PLAYBOY: But it’s a battle you can’t win.

BROOKS: You can win a conditional victory, I think. It all boils down to scratching your name in the bark of a tree. You write M. B. in the bark of a tree. I was here. When you do that—whatever tree you carve it in—you’re saying, “Now, there’s a record of me!” I won’t be erased by death Any man’s greatness is a tribute to the nobility of all mankind, so when we celebrate the genius of Tolstoy, we say, “Look! One of our boys made it! Look what we’re capable of!”

So I try to give my work everything I’ve got, because when you’re dead or you’re out of the business or you’re in an old actors’ home somewhere, if you’ve done a good job, your work will still be 16 years old and dancing and healthy and pirouetting and arabesquing all over the place. And they’ll say, “That’s who he is! He’s not this decaying skeleton.”

I once had this thought that was so corny, but I loved it. It was that infinitesimal bits of coral, by the act of dying upon each other, create something that eventually rises out of the sea—and there it is, it’s an island and you can stand on it, live on it! And all because they died upon each other. Writing is simply one thought after another dying upon the one before. Where would I be today if it wasn’t for Nikolai Gogol? You wouldn’t be laughing at Young Frankenstein. Because he showed me how crazy you could get, how brave you could be. Son of a bitch bastard! I love him! I love Buicks! I love Dubrovnik! I love Cookie Lavagetto! I love Factor’s Deli at Pica and Beverly Drive! I love Michael Hertzberg’s baby boy! I love rave reviews! I love my wife! I love not wearing suits! I love New York in June! I love Raisinets! Which brings me, Mr. Interlocutor, for the last time, to the question: Would you or would you not care for a Raisinet?

PLAYBOY: Sure. Why not?

BROOKS: Sorry, kid. They’re all gone.