It’s sad to say it, but Frank MacShane’s new biography of John O’Hara (The Life of John O’Hara) is a hell of a lot more interesting for us today, and makes a better novel, than practically all the fourteen novels O’Hara ever wrote. No seemingly major American fiction writer has ever dated with such suddenness that he now reads more like an artifact than an artist. Mr. MacShane happens to be a very decent, compassionate bloke, as he proved in his last study of another unhappy American writer, The Life of Raymond Chandler (1976), and one can trust his honorable intentions when he says in the preface to his newest book that his purpose “is to renew an interest in O’Hara’s work through a look at his life.” But what it will do for most of us is confirm the fact that Black Jack O’Hara was a more unsavory and driven character than anything in his fictional shooting gallery, including the classic bastards in his short stories.

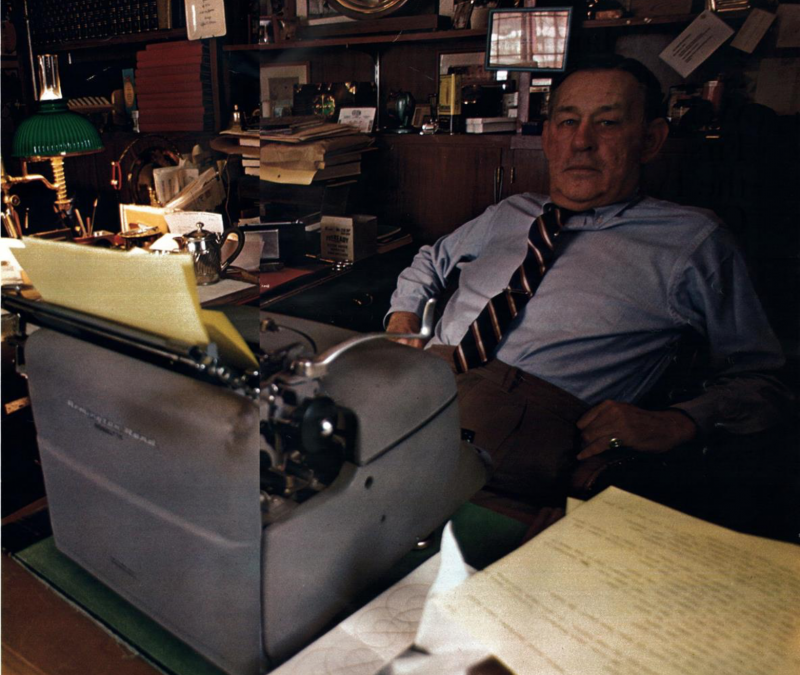

What went wrong with the bulk of his “mature” novels, why do they make us groan when we see the titles on the bookshelf—Ourselves to Know, The Big Laugh, Elizabeth Appleton, The Lockwood Concern, The Instrument, Lovey Childs: A Philadelphian’s Story, etc.—and imagine taking them down for a nostalgic curl-up? The simple truth is that they are uninspired deadwood, with a vengeance. By the time he wrote them O’Hara had become a compulsive writer, determined to bring out a book a year, and the prose could have been a Stock Exchange listing for all the passion it contained. For the last fifteen years of his life, until he died in 1970 at the comparatively young age of sixty-five, he replaced drinking with staying up all night racing the keys of his Remington Noiseless. The results were mechanical, frozen panic, dressed up as fiction.

But even before this final descent into the hammerlock of his obsession with production for its own sake, his self-designated role as a “chronicler of American life,” “a social historian,” and “a latter-day secretary to society” caused him to pad his big books with slab on slab of exhibitionistic detail that an earlier O’Hara would have thumbed his nose at. Mr. MacShane rightfully considers the best of these inflated monsters to be From the Terrace (1,088 pages in paperback!), but he is fair enough to quote the lines from an Alfred Kazin review in 1955 that sum up our almost physical recoil from the book now. “We are deluged, suffocated, drowned,” wrote Kazin, “in facts, facts, facts.” It is true enough: in the silence of his long Princeton, New Jersey exile, where O’Hara spent the last twenty years of his life as a synthetic country squire, the reverse snobbery of the ex-newspaperman, who thought rifling Who’s Who and the Yale Yearbook was the height of veracity, became a kind of mania. In a peculiar but perhaps inevitable parody of American technology, O’Hara got as close to becoming a duplicating machine as it’s possible to get to keep his ghosts at bay.

These ghosts are what fascinate us in the man because they are sad ghosts of America itself; and when the young O’Hara let them out in early works like Appointment in Samarra and Butterfield 8 we knew that a genuine victim of this acutely class-conscious, putatively classless society of ours was speaking from real hurts and envies shared by others. In one man’s opinion, these early novels were O’Hara’s freshest and most original, but even they are ’30s period pieces today, flaunting an ear for dialogue that is no longer spoken: “screw, bum,” “can that stuff,” “perfectly vile,” or this little, dated bit of O’Hara preening from Butterfield 8: “I never saw a Phi Beta Kappa wear a wristwatch.” O’Hara exaggerated the externals of American life because he personally was so smitten by them, and this is surely one reason why his reputation has shrunk to a husk of what it once was. But it is to Mr. MacShane’s credit that he patiently makes us understand the class distinctions and social demons that tormented O’Hara into becoming a monumental trivialist.

First, consider another American Irishman who was born only a year before O’Hara, in 1904—James T. Farrell. Farrell never went to dancing school or had a father who was a successful surgeon, as did “The Doctor’s Son” (the title piece of O’Hara’s first book of short stories). He saw society from the gray-brick prison of the Chicago Irish ghetto, and even though he might be said to have endlessly counted those bricks in the tedium and drabness of his later books, he never lost his bearings. His fight was defined for him early on. He did not suffer from what we are accustomed to call “identity problems,” even when he ran out of gas as a literary engine.

But O’Hara was an Irishman of another, more subtle, kind of pride—and sometimes total lack of pride—who was scarred at a very early age by a small-town social discrimination that came down very hard on even the comfortable Irish Catholic minority. The town was Pottsville, Pennsylvania (called Gibbsville in the novels and stories), a little burg of 25,000 inhabitants in the coal-mining region of the northeastern part of the state. By the time O’Hara came on the scene, the first of eight children born to Dr. Patrick O’Hara and the former Katharine Delaney, Pottsville had barely healed the acute “social, religious and economic hatreds,” in MacShane’s words, that had split it in the 1870s and 1880s.

Still at the bottom of the heap were the immigrant miners, many of them Irishmen, who had fought the exploitation of the coal operators with violence—this is where America’s own “Molly Maguires” came from, and they were hanged by the dozens in Pottsville—and at the top were the “nobs,” the Protestant families who controlled the banks, the railroads, the canals, and had the old money. O’Hara’s people were in the solid middle, his father was chief resident surgeon at the local hospital, and his family lived on posh Mahantongo Street (called Lantenengo in Appointment in Samarra), but it was soon made clear to the young John that he could never be a nob or even a son of a nob.

It was as if the Pottsville swells hadn’t so much civilized this jug-eared rough boy as daintified him, like manicuring a bulldog’s toenails.

“They” sent their children to Yale and Wellesley and Princeton and Bryn Mawr; “they” traveled to Europe and had summer places on Martha’s Vineyard and Cape Cod. (“They” also lived on the upper reaches of Mahantongo Street, while O’Hara’s family, naturally, lived in the middle.) Instead of Yale, which was to become a pathetic obsession with him for the rest of his life, the young O’Hara was kicked out of three Catholic prep schools and never made it to college. And instead of Martha’s Vineyard and Europe, the big summer events in O’Hara’s teenage life were picking up mill girls in Pottsville and getting into fistfights at the Schuylkill Country Club. He was an outsider from the start, but close enough to the nobs through sheer proximity to be able to imitate their dress, manners, and lingo and finally to end his days in Princeton as a bogus nob himself.

Was it his ambiguous position—the tough mick who was as fastidious as a movie butler about knowing the difference between a salad fork and a fish fork—that made him such a virtuoso mimic and microscopic observer in his early work? Probably. He seemed to develop his sharp eye and even sharper ear as weapons to protect his own vulnerable skin. He and his self-made, iron-pants father had grim physical confrontations during the growing-up years, and by the time he was in his twenties O’Hara had already earned a reputation for himself as a drinker and a brawler; yet there was something almost girlish in his knowledge of what a hemline should look like and of what kind of pumps were to be worn at a tea dance. It was as if the Pottsville swells hadn’t so much civilized this jug-eared rough boy as daintified him, like manicuring a bulldog’s toenails.

But, as Mr. MacShane shows us, it was just this gloss that made him so attractive to the New York scribbling stars of the late ’20s (F. P. Adams, Stanley Walker, Heywood Broun, Richard Watts, Wolcott Gibbs, etc.) when the precocious twenty-three-year-old left Pottsville behind him for good and stormed the one and only Tiffany town for a dandy of his tastes. Even though in later years he hid smugly behind the mask of “ex-newspaperman” when his work got faulted for one literary reason or another, the truth was that O’Hara had already chalked up a lousy (and lazy) track record as a reporter on the Pottsville Journal and the nearby Tamaqua Record before he reached Manhattan. He wasn’t to do much better in successive jobs on the New York Herald Tribune, the Daily Mirror, and the youthful Time magazine, but it didn’t seem to really matter. He was stylish and outrageous enough to win an immediate following—he once smuggled a girl disguised as a man into the Yale Club bar and wrote a story about it—and for a while he seemed to be that rare thing, a first-rate man’s man and ladies’ man as well. He could drink, dance, fight, pick up a sleeping companion, and turn out a sharp, funny sketch practically all in the same day. As he later cutely put it—about part of his pizzazz anyway—“I can write faster than anyone who can write better, and better than anyone who can write faster.” (The phrase is also attributed to A. J. Liebling; who stole what from whom?)

It was The New Yorker, of course, that came through for O’Hara, although he and editor-founder Harold Ross never really got along and didn’t speak for the last years of Ross’s life (he died in 1951). The timing was right. The magazine was only three years old when O’Hara hit New York, and he and Ross had one big thing in common: they were both self-educated hicks who were pop-eyed enough about the big town to be fascinated by all the minutiae that the natives took for granted; and they both had a yen for the rich and powerful. Thus O’Hara found a short-piece home for the next four decades (although he boycotted The New Yorker for ten years because of hurt feelings), and today there is every good reason to think that this is where he did the work that has the best chance of surviving. Stories like “Where’s the Game?,” “Are We Leaving Tomorrow?,” and “A Respectable Place” give the nasty, vintage O’Hara vision in less than 3,000 unbeautiful words. They are written with a casual shrug, so to speak, which makes them all the more effective than the dreary marathons he turned to when he left New York for the soft suburbs.

O’Hara was not a pleasant man during those successful Manhattan and (shuttling back and forth) Hollywood years—roughly 1930 to 1945; that first, gallant impression had faded fast. He was Mr. Drunk-and-Insulting at such places as the 21 Club and the Brown Derby, he beat up women in public, he boasted about getting the clap, and his self-destructive urges clearly showed in his favorite stunt of sitting on the edge of a penthouse windowsill and dangling one leg over the street. But he was more alive even when snotty and out of control than he ever was later on, when he fancied himself some kind of American Trollope and lusted after honorary degrees and even the Nobel prize (“I am the best novelist of my generation and deserve it”). Before the end of this high-balling period, which was capped by the success of Pal Joey on Broadway, he also participated as abrasive but undefensive friend for the last time with some of the liveliest writers of his generation: William Saroyan, Clifford Odets, Budd Schulberg, and John Steinbeck.

From the end of World War II to the end of his own private war, O’Hara increasingly cut himself off from almost all his contemporaries except those who flattered him. Starved for respect and approval, despite the fact that his worst novels were beginning to make a lot of money, he wrote fawning letters to such as Lionel Trilling after the latter gave him a good review on one of the small-selling but better-written collections of short stories, Pipe Night. He also basked in the occasional approval coming from an over-the-hill Ernest Hemingway, and with a shameless mixture of loyalty and bootlicking paid Hemingway back by beginning a New York Times review of Papa’s most feeble novel this way: “The most important author living today, the outstanding author since the death of Shakespeare, has brought out a new novel. The title of the novel is Across the River and into the Trees.”

“It is pretty hard for most writers not to be jealous of me, because I make it look easy and they know it is not.”

These egregious tactics couldn’t work with William Faulkner, however. It was Faulkner who nailed O’Hara right where he lived and hung the phrase on him that still echoes for us today: “a Rutgers Scott Fitzgerald.” As Mr. MacShane tells it, Faulkner was in New York in 1950 on his way to Stockholm to collect his Nobel prize, Bennett Cerf, who published both Faulkner and O’Hara at Random House, gave a dinner party for Faulkner to which he invited O’Hara and his second wife. At some point Faulkner needed a light for his cigarette and O’Hara whipped out his gold lighter. Faulkner “commented on the handsomeness of the lighter” and O’Hara, right then and there, in what seemed like an act of high generosity, gave it to him, saying: “Phil Barry [the playwright] gave it to me and I’d like you to have it.” Faulkner apparently took the lighter with a minimum of fanfare and put it in his pocket.

But O’Hara was furious. Although Mr. MacShane doesn’t say so, O’Hara was a sentimentalist who could turn vicious and childish if he didn’t have his way. Philip Barry was recently dead, and O’Hara wanted Faulkner to appreciate publicly the symbolic link involved in the passing on of the lighter. Faulkner, naturally enough, had other, deeper fish to fry than this fraternity game of weepy brotherhood, and refused to write O’Hara a note of thanks when Bennett Cerf pressed him. “I didn’t want his lighter,” Faulkner said. “I didn’t ask him for his lighter. Why should I write him a letter?”

Faulkner’s remark about what kind of Scott Fitzgerald O’Hara turned out to be sums up in a thimble so much that was second-rate about the Pottsville Flash. (Nor is this intended, perish the thought, as a knock at Rutgers; let’s just say that it never pretended to Princeton style, and the kind of extravagant flair Faulkner was getting at is much better suited to its Ivy League neighbor twenty miles to the west.) Where Fitzgerald had been known to strip the Brooks Brothers shirt off his back and give it away with a happy smile, O’Hara was enough of a jigger-measuring materialist to want something in exchange for the grand gesture. His impulses were poetic, perhaps, but his rewrites were all in businessman’s prose. You might say he ended up as a wealthy, bugged, small-town banker of the world, priding himself on such things as his four-door Rolls Royce Silver Cloud III (with initials painted on) and eating his heart out because he was blackballed by the Brook Club in New York (“I am disheartened by the number of creeps who have been creeping into the Century”) and had lost out to that damn Faulkner once again for the Pulitzer Prize.

Mr. MacShane, bless his heart, is not only a scrupulous and fair biographer, he is also a believer—although hardly a holy roller about it like the indefatigable Matthew Bruccoli, who published his cheerleading biography, The O’Hara Concern, a few years back. Nonetheless, Mr. MacShane (an American Irisher himself, with nob-type degrees from Harvard, Yale, and Oxford that would probably have caused O’Hara to kneel down and kiss his behind) concludes his authoritative picture of the life with the unmealy-mouthed words that O’Hara was “one of the half-dozen most important writers” of his period. Conceivably this could even be true, but O’Hara’s period is not ours, and it’s a good guess that at least ninety percent of all those thousands and thousands of words O’Hara machined out have already gone to their final resting place in spite of Mr. MacShane’s noble efforts at rehabilitation.

No, what makes O’Hara grotesquely alive for us now—apart from a handful of the stories—is the obsessive, unremitting monomania of the man, which Mr. MacShane has to show because he is an honest reporter. As O’Hara felt more neglected by the world’s awards committees, so did his assessment of himself seem to climb in direct ratio. It isn’t every literary daddy who will write to his only daughter a few years before his death, “It is pretty hard for most writers not to be jealous of me, because I make it look easy and they know it is not.” And it isn’t every novelist who will use his very gravestone as a final answer to his critics. “Better than anyone else,” O’Hara says in his own epitaph in the old Princeton cemetery, “he told the truth about his time.” It all sounds like the brassy attempts at self-justification of a man who feels, deep down, that he has blown it.

[Photo Credit: Carl Fischer]