Collected in Latins Are Still Lousy Lovers

It would seem that John Huston has an obsessive to make movies the hard way. He picks the most difficult, inaccessible, uncomfortable, even dangerous, locations—where almost everyone in the company gets sick except him—and then takes a quiet delight in tittuping along vertiginous emotional ravines with whatever notoriously high-strung people he has cajoled and charmed into coming with him.

Over a decade ago, in a novel called White Hunter, Black Heart, generally assumed to be a revealing portrait of Huston, Peter Viertel told, under a not too opaque fictional guise, the story of the tribulations allegedly endured by those who went with Huston to the Congo to film The African Queen. Some years later, Huston did a reprise, this time in French Equatorial Africa, where he made The Roots of Heaven in a temperature that averaged 124 degrees. The cast was uniformly miserable, with at least one member, Juliette Greco, suffering recurrent attacks of malaria fever a year after she had returned to Paris.

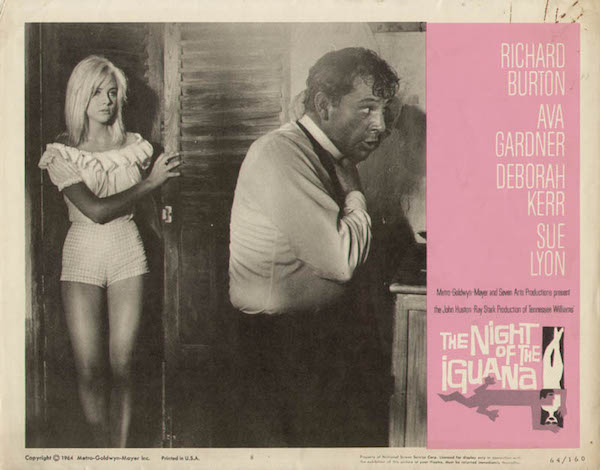

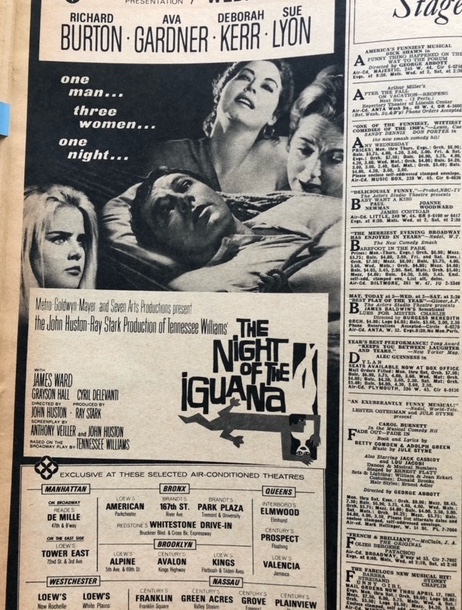

Huston has made other films on slightly less challenging terrain, but under the harrowing circumstances which are apparently his idea of the happy norm. For the movie version of Tennessee Williams’ play The Night of the Iguana, he picked a Mexican jungle, near Puerto Vallarta, an isolated little fishing village on the Pacific coast, then burgeoning into a resort. It was not the worst movie location he had ever chosen, but it was bad enough. As for the personnel, he assembled what was probably the most combustible cast he has had to date, augmented by a chaotic assortment of wives, husbands, paramours, children, dogs, visitors, Mexican technicians, laborers, other employees and hangers-on. It was exactly the kind of steaming, teeming, tense, nervous atmosphere in which Huston does his best work while everyone else goes to pieces: a perfect setup for some sort of buffoon version of an auto-da-fé in a madhouse, with Huston dominating the scene, low-voiced, calm, deceptively gentle of manner and happy as a sandboy.

I arrived in Puerto Vallarta early on a Saturday morning, and by nightfall I had seen Ava Gardner in the flesh, as well as Huston, Tennessee Williams, Deborah Kerr, Sue Lyon and, of course, that anything but anonymous duo, Burton and Liz (this was before their marriage), apparently insouciant and inseparable, the Bobbsey Twins in Mexico. I also saw—and wished I hadn’t—a wooden crate stuffed to the brim with bright green iguanas, who wriggled once in a while but not often, because their lips were sewed together and they were dying.

I made two trips that first day to Mismaloya, where 283 native laborers (and 80 burros) had been working frantically to build a group of houses, a restaurant, and a movie set on the edge of the jungle, where before there had been only dense trees and steep rocks. Most of the company were scheduled to move there over the weekend, an event they regarded with mitigated enthusiasm. There was nothing there but the new wooden buildings and the forest and then the jungle, with jaguars, civet cats, and mountain lions. The electricity and the plumbing were even more unstable than in Vallarta; the place was alive with scorpions, spiders, midges, mites, mosquitoes, flies, chiggers, snakes, and land crabs; and everything—including people, food, and all supplies—had to come eight miles every day from Vallarta by water, which is the only way to get there. The routine is to walk through the water on the beach until you can climb into a dugout punt, which is then propelled, by a Mexican with a pole, out to a speedboat, which you scramble into as best you can, depending on your age, sex, and agility, since the rim of the speedboat is considerably higher than that of the punt. It is made even more of a sporting feat when you come back at night, the waves are rocking both boats and no one has remembered to bring a flashlight.

Huston had a small but provocative entourage of friends, in various official and unofficial capacities, with other guests slated to arrive.

The heat was intense, and I was drenched with sweat by the time I went to bed that night back in the hotel at Vallarta. In addition to the black-and-blue marks sustained from climbing in and out of the boats and stumbling up the rocks in Mismaloya, my face, neck, arms, and legs were covered with insect bites. I lay on the bed listening for hours to the riotous, insistent music of a mariachi band playing at a nearby open-air spot for last-ditch revelers. I got up to take a Miltown, but when I poured the mineral water from the bottle into the glass there was a dead earwig in it. Finally, I fell asleep, only to be awakened around 5:00 A.M. by Tennessee’s little dog, which had hurdled over the balconies outside our rooms and landed with a bounce on my stomach. Oh well, I thought (after I stopped quaking), thank God it wasn’t an iguana. At least I was only going to be there one week. The movie company was stuck for three months.

As if it were not complicated enough to have Burton playing love scenes with Ava and Sue, while Elizabeth watched from the sidelines, there were plenty of subsidiary undercurrents. Viertel, who had written the novel which everyone knows was inspired by Huston, was there with his wife, Deborah Kerr. It was an extra bonus of titillating coincidence that when Ava made The Sun Also Rises in Mexico in 1957, Viertel was at that period her constant companion. This time, Ava arrived with her brother-in-law and her maid. To be on the safe side, Ray Stark, the producer, had hired two personable young men to serve as her escorts, protect her from the press and, in general, keep tabs on her. Michael Wilding, one of Elizabeth’s ex-husbands, was Burton’s agent, and he had been down there the week before I arrived. The rumor was that Eddie Fisher, then the present incumbent, would be asked to appear in December as a performer at the opening of the Posada Vallarta, a new super-deluxe hotel. Liza Todd, Elizabeth’s child by the late Mike Todd (husband No. 3), arrived with Burton and her mother, along with Liz’s male secretary (who, in turn was visited by two of his friends) and Liz’s English chauffeur and his wife, who, according to the newspapers, were given the trip by Liz as an all-expense-paid holiday.

Tennessee came down with a friend named Fred, and later an elderly woman and her brother (“She’s my dearest friend,” said Tennessee) also arrived to visit. Sue Lyon’s boyfriend, Hampton Fancher 3rd, was there, and he was rumored to have invited some of his friends down. Sue also had a paid companion with her, a pretty Hungarian woman named Ava Martine, and a female schoolteacher who was supposed to be giving her daily lessons so she could get through high school. (“I’m only seventeen,” Sue kept saying. “Don’t forget, I’m only seventeen!”)

The teacher seemed a little vague when I asked her about the curriculum. “The usual things,” she said.

“Well, what?”

“Oh, English, French, history.”

“No math?”

“Oh, yeah, math. Sure.”

Huston had a small but provocative entourage of friends, in various official and unofficial capacities, with other guests slated to arrive, among them Buckminster Fuller, the architect (most celebrated for his invention of the Dymaxion House and the geodesic dome), and Rosa Covarrubias, the widow of Miguel Covarrubias, the Mexican artist and anthropologist. Ray Stark kept popping in and out—once flying down from New York for just one day—with his friends and associates. Kim Novak heard about all the fun-and-games and telephoned the New York office of Seven Arts to ask if she could drop down to Vallarta for a spell. “That’s all we need!” muttered one of the press staff. In addition, the secretaries, hairdressers, cameramen, technicians, and other sundry employees and supernumeraries had friends or relatives or sweethearts either on the spot or in transit. Wives departed one week, and girlfriends arrived the next; visiting boyfriends brought their own epicene boyfriends; and what with all the heat and all the drinking and all the traffic, Huston certainly had need of that orphic mesmerism for which he is justly famous.

Huston, serene and relaxed, was in the midst of everything, with his loping walk, his tall (six foot three), thin, figure apparently impervious to the heat, hatless, cool clean in white shirt and pants.

He moved through the whole loony brouhaha as if he hadn’t a care in the world—or a nerve in his body. When it rained two days in a row and all shooting stopped, he sat in a bar playing gin rummy for hour after hour as if that were what he had come down there to do. Everyone else was on tenterhooks, but he stayed relentlessly casual. He was in control of every situation, and looked as if nothing fazed him or ever would. To the interlopers and visiting firemen who tried to horn in on the game he was patiently courteous. Once, a fashion model—somebody or other’s girlfriend—sat down beside him, uninvited, and kept trying to look at his cards and offer helpful comments. The only sign he gave was to glance at her occasionally with a deadly smile of great and phony sweetness that lighted up his face, and instantly vanished. If I had been in her shoes, I would have gotten the message, and evaporated.

He was the same when he was in action, infinitely calm, inhumanly pleasant. They rehearsed a bus scene over and over at noontime on the cobblestone street under a burning sun. Everyone else was dripping with sweat, the crew men stripped to the waist and wearing Mexican straw sombreros to shade their heads, the makeup running off the women’s faces. Huston, serene and relaxed, was in the midst of everything, with his loping walk, his tall (six foot three), thin, figure apparently impervious to the heat, hatless, cool clean in white shirt and pants. For a while we sat inside the bus, which was like a blast oven, chatting and joking with Ray Stark and Gabriel Figueroa, the Mexican cameraman. Huston seemed as comfortably at ease as if he were sitting in the air-conditioned bar at “21”. I was the first to chicken out, and he affably accompanied me to a small cantina, swarming with flies, where he had a couple of warm beers and talked of mutual old friends, the new plays on Broadway, his past films and his next job, which was nothing less than to direct the $20,000,000 movie version of the Bible, to be shot in Egypt and Italy. He said he was looking forward to it, and I was sure he meant it, although most other directors would have fainted at the prospect.

If Huston is strong and tough and intelligent, so is Burton. Whatever John can endure and whatever he can dish out, Richard can take. Although in no way so devious or so subtle as the older man, the Welshman is, in his own stormier style, equally a powerhouse. On the set, their mutual respect and understanding were evident. The role of the drunken, guilt-tortured renegade priest was a good one for Burton, and they both knew it. He needed it too, after the stultifying sogginess of Cleopatra, and The V.I.P.’s, in which he had a part that demanded nothing of him and to which he gave precisely that. He needed to get back into serious acting, with a real director, if only as a warm-up for his forthcoming appearance in Hamlet on the Broadway stage, under the direction of Sir John Gielgud.

Burton is much more magnetic in person than in photographs or on the screen. He has a coarse skin, but he glows with vitality and energy, and his eyes are a hot blue. He also has, almost to excess, a rugged, hell-raising maleness about him, a quality that makes men like him immediately and women get weak-kneed and start to gibber helplessly. His voice is marvelous—deep, plangent, and musical. When not in one of his black Welsh moods, he is a gifted conversationalist, at times brilliantly funny, with a spruce facility for words, as when he described one of the hangers-on—“He looks like a dormouse, a dormouse with a wig”—or referred to Peter O’Toole as “a tall, thin praying mantis.” He and O’Toole are kindred spirits. “When we started to film Becket together,” he said, “we knew that everyone expected us to be drunk the whole time. So we decided not to touch a drop, and we didn’t—for two weeks. But then came St. David’s Day, and we said, ‘We have to celebrate, just for today,’ so we went to a bar, and O’Toole ordered a quart of Irish whisky. He stood at that bar and held the bottle to his mouth and went glug-glug-glug and drank the bottle while I stood and stared at him. I never saw anything like it. When he finished, he put the bottle down on the bar and just stood there a moment. Then his eyes sort of glazed and he fell straight down—bam! He was out for forty-eight hours.”

Burton himself was drinking what he called “Mexican boilermakers”: straight shots of tequila with beer chasers. He hadn’t shaved for days—in keeping with his role in the film—and he hadn’t slept the night before, but he looked great.

(Burton said that O’Toole’s contracts give him St. Patrick’s Day off, while his own have a similar proviso for the Day of St. David, patron saint of Wales. However, since the latter day is March first, and the filming of Becket did not start until May, I can only conclude that either Burton availed himself of that poetic license for embellishment as common to the Welsh in storytelling as to the Irish, or else that he celebrates St. David’s Day out of season.)

We were sitting drinking one morning in the Oceana bar, and Burton was in fine fettle, telling story after story of his boyhood in Glamorgan and of his father, now dead, who was a miner. “One night the old man was coming home drunk when he fell and impaled himself on a bough. He lay there in the dark, covered with blood and singing Welsh songs at the top of his lungs, till a neighbor happened by and struck a match to see if ’twas anyone he knew…. He got help and took my father to a hospital and then sent for me. I was in the waiting room when an English nurse came out and said, ‘Does anyone here speak Welsh? We’ve got an old man raving in there, and I think he’s delirious.’ I said I spoke Welsh, and she took me into a room and there was my old man all battered up and yelling away. I said, ‘That’s my father,’ and the nurse said, ‘Well, ask him if he knows you,’ so I said in Welsh, ‘Do you know me?’ and he started right off, ‘I bloody well do, you so-and-so….’ You know, that old man had the flu once, with a high fever, and he was very bad, so I went home to see him. He was lying in bed and he looked half gone. I stayed a while in his room and then I started to tiptoe out. He opened one eye and said, ‘Where’re you going?’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘I thought I’d go over to The Miners for a while’—that’s a pub—and he said, ‘I want to go with you.’ I thought I might as well grant him his last wish, so I got my five brothers and we half carried him there and held him propped up against the bar. We ordered a round of boilermakers, and the old man said, ‘Just leave ’em right there, boys.’ Then he drank his own and all of ours. We carried him home, and the next morning he woke up cured.”

Burton himself was drinking what he called “Mexican boilermakers”: straight shots of tequila with beer chasers. He hadn’t shaved for days—in keeping with his role in the film—and he hadn’t slept the night before, but he looked great. “The script says I’m supposed to be drunk and feverish,” he said, “and I’m a Method actor.” Liz had stayed with him all the previous afternoon, when he sat drinking in the bar, and that night they were joined by a wire-service newspaperman who made the mistake of trying to match drinks with Burton, which is hard to do. After the newsman had staggered out twice in the street to throw up, he finally disappeared, and when he showed up later that night at the hotel, he was covered with grease and dirt. “The bastards tried to tar and feather me,” he kept saying. We never did find out what happened to him. The casualty rate among the press in Vallarta was high: dysentery, food poisoning, massive hangovers—and acute frustration, among other things.

That last affliction was possibly the most aggravating. From the start, the relations with the press had been fraught with mutual hostility. When Burton and Elizabeth arrived at the airport in Mexico City, they were met by a raucous mob of fans, photographers, and journalists. In the melee, Elizabeth lost a shoe; a press agent was kicked, and in retaliation took a swing at a couple of photographers; and Burton, perspiring and angry, when asked if this was his first visit to Mexico, replied “Yes, and I hope it is my last.”

The Mexican press got huffy because it was not invited to Vallarta. The papers soon started writing derogatory stories about the stars. Publications all over the world wanted to send representatives to the scene; the housing situation became desperate, and the press agents even more so. Burton blew up at a photographer and strode off the set with a blast of colorful expletives; Ava refused to work if any photographers were around anywhere; and the set at Mismaloya was ordered closed to the press. None of the Fourth Estate was permitted near the stars’ living quarters. “They want to know what we are doing behind these closed doors,” said Burton. “What do they think we are doing? We’re playing gin rummy, of course!”

It was Ava who was the contentious one, and everyone there was leery of her, except Huston, and even he would have thought twice before doing anything that might antagonize her or send her into one of her legendary and dangerous moods.

The one exception was Deborah who, with Viertel, was living apart from all the others, in a house across the river on the opposite side of town. I went over there on two occasions and found it a refreshing oasis of sanity, compared with the tempestuous philliloo that raged elsewhere. “I do not dig these people,” said Deborah, quietly. “However, I am getting a little bored with the constant assumption that I am the one safe, sensible, dependable element no one has to worry about. I think it would serve them all right if I suddenly developed temperament, had hysterics, became an unmanageable sexpot, threw temper tantrums, or something. But I suppose I won’t. I’ll do my job the best I can, and Peter and I will try to live as normal a life as possible, under the circumstances.”

It was Ava who was the contentious one, and everyone there was leery of her, except Huston, and even he would have thought twice before doing anything that might antagonize her or send her into one of her legendary and dangerous moods. He had ordered the set closed because of her. “Christ, I hate rehearsing!” she had said, and we all knew it was because she was nervous and didn’t want anyone watching her. Where the press was concerned, she was her customary self, as amiable as an adder. She had insisted that her contract protect her from being photographed without her permission and that it give her the right to O.K. or reject any pictures that were taken. “She’s paranoiac on the subject,” said a member of the company. “She’s scared stiff,” said another. “She’s never had a really good director before and she’s never really acted. She knows she’s up against a stiff challenge, so every time she thinks of it, she takes a couple more drinks and then she gets hostile.”

Ava has a personality like compressed steam. All of us had been warned that it was impossible to speak to her and that even if we stared at her, it was at our own peril. When I saw her that first day, she was sitting beside Burton in the bar, and she was giving him the full benefit of her green eyes and radiant smile. Gjon Mili, the grizzled, veteran fast-motion photographer, and a wily Albanian to boot, unobtrusively raised his camera and started snapping pictures quickly. She gave him a look Medusa would have envied, and he put the camera away. For days afterward, she demanded to see the proofs, saying ominously, “Someone had better take a good look at my contract!”

Actually, even though she was then forty, she looked better than she did when I had last seen her six years before. She was wearing her dark hair pulled straight back from her face, which showed off to best advantage her wonderful cheekbones and jawline; and she used very little makeup. There is about her physical presence a glistening, tingling quality that immediately sets her apart from the others as she moves into a room, the Antigone whom all men desire.

Both Elizabeth and Ava are as spoiled as medieval queens. They expect men to fall at their feet, and they are accustomed to being catered to and having everything done for them, their imperious whims fulfilled with alacrity.

When I was there, they were all at the initial stage of being terribly polite to each other, but Elizabeth wasn’t taking any chances of overlooking her own interests. Every day she showed up at lunchtime, looking blazingly beautiful and making it obvious that she considered Burton her property. As soon as his working hours were over, she usually whisked him back to Casa Kimberly, the biggest house in Vallarta, which she rented, at $1,500 a month, for herself, Burton, and their entourage. At one point, we were told that she had bought the house and given it to Richard for his birthday, but when he was asked about this, he just snorted. “What in God’s name would I want with a house here?” he said.

Both Elizabeth and Ava are as spoiled as medieval queens. They expect men to fall at their feet, and they are accustomed to being catered to and having everything done for them, their imperious whims fulfilled with alacrity. Just before I left, Ava was about to move into her fifth house, having first accepted and then rejected the other four in turn. The last one was high on a cliff, practically inaccessible except to a mountain goat, and everyone was speculating on how she was going to make it down to the water at dawn in order to get across to Mismaloya and the set. She had announced that she intended to water-ski to work each morning.

Compared to the two experienced sirens, Sue Lyon was like a fluffy kitten capering around the set, or perhaps a baby fox (or a foxy baby?). People kept saying that maybe Burton would fool everyone and run off with Sue, but that seemed the wildest of press-agent dreams, although, admittedly, anything was possible in that atmosphere. Someone even sent out a wire-service report saying that Ava was going to marry Emilio Fernández, the famous Mexican film director (The Pearl, The Fugitive, María Candelaria), an old friend of Huston’s, who was serving as associate director on the movie, a purely honorary title. Mexican regulations require that any foreign company making a film there must hire a local director, even though his sole function is to put in an appearance on the set every day, but otherwise keep out of the way. Emilio, who is known to everyone as “El Indio” (The Indian ), is a huge, flamboyant man with a sort of rodomontade panache, whose conversation is a farrago of lively tales dealing, for the most part, with the men he has shot and the girls he has made. He was a bonanza for the press, always accessible, always ready to drink with us and keep us entertained for hours on end, but it was hardly likely that he would capture one of the stars, even though his prowess is by no means all myth. He was barely on speaking terms with Liz, since her arrival in Mexico, when he charged onto the plane, wearing an enormous Pancho Villa-type sombrero and a gun belt with pistols, and grabbed her by the arm saying, with his strong Spanish accent, “Follow me!” at which Burton shouted, “Get this man out of here before I kill him.”

Serving as a sort of atonal counterpoint to the intricate orchestration of personal relationships in the film company was the local please-pass-the-marijuana and let’s-have-an-orgy set. This is a coterie of rich, elderly American divorcées who stave off loneliness and boredom by surrounding themselves with venal young men, fair of face and frolicsome of manner. You could see them at the beach club in the morning, starting their daily drinking schedule: the young men sporting imitation leopard or zebra bikini-type bathing briefs, their torsos carefully oiled, with every muscle rippling and gleaming like pin-up pictures in a weight lifters’ magazine; their aging protectresses heavily made up, bejeweled, clad in expensive beach garb that defiantly revealed their sagging charms. (“Everyone seems to turn queer down here,” said Burton, watching them. “I hope it’s not catching.”) For this group, the ball was never-ending. Night and day the music played, the drinks flowed, the laughter rang—shrill but constant. At one of their little Walpurgis Night galas, so I was told, the hostess, a woman in her sixties, took off her dress and pranced around in her underclothes, while kindred diversions were going on in every bedroom and a jolly time was had by all. I must say that none of the stars was ever present at these festivities, although other members of the company were.

To the natives of Vallarta, these hi-jinks were a source of amazement and contempt, but the pay was good. The left-wing Mexican press, however, was alarmed at the transformation of the simple fishing village, and at least one publication, Siempre, denounced it in savage terms: “Mexico can still save Puerto Vallarta, whose people are being criminally despoiled of their land, their beaches, their way of life…. [Mexican] children of 10 and 15 are being introduced to sex, drinks, vice and carnal bestiality by the garbage of the United States: gangsters, nymphomaniacs, heroin-taking blondes….”

It seemed evident that Huston could have made the movie easier at almost any other Mexican location. The logistics of the undertaking were staggering, when you consider that every single thing, from bulldozers for clearing the land to the bathroom fixtures, had to be ferried by barge to Mismaloya, after first having been transported to Vallarta from Mexico City or Mazatlán. (Even the dog food for the various pets had to be flown in daily to Vallarta and then taken by boat to Mismaloya.)

The drain on Vallarta’s meager supplies began to show while I was still there. Some of the local hotels, restaurants, and stores ran out of beer, soap, facial tissues, toilet paper, fresh pineapple. It got to be a joke that whatever you wanted, you couldn’t get because it had all gone to Mismaloya. The prettiest maids got jobs over there, and the carpenters and plumbers working on the new Vallarta hotel were commandeered by the film company, and had to be replaced by others imported from Mexico City.

This was as nothing to the physical stress and strain. All water would be suddenly shut off just as you came back to your hotel, dripping with perspiration and eager for a shower. The electricity would go off for hours at a time, and, although no one used it much-—if you turned on a light at night to undress, the wall was soon covered with crawling bugs—the effect on the refrigeration of food was disastrous. Dysentery was the order of the day, and everyone took Entero-Vioforma pills, although occasionally, because of the language barrier, there would be a mixup. One man discovered that he had been dutifully swallowing what he thought were pills for bronchitis but turned out to be an aperient. The only doctor was a local resident, and he was certainly kept busy. In the week I spent there, the wardrobe designer fell on the Mismaloya rocks and broke a toe; the secretary to one of the press agents tripped while climbing out of a boat and cut her shoulder on an iron spike; Liz got chiggers in her feet that had to be dug out with a knife (“That girl has had thirty operations in all,” Huston told me); I got two chiggers in my ankle (“they burrow until they find a vein and then they enter the blood stream, and after that the only time you can see them is when they are passing across your eyeballs,” said the fashion model cheerfully); a member of the publicity department came down with the flu; and a free-lance iguana escaped custody and bit an electrician on the leg. They grabbed him and sewed his mouth up right on the street. (The iguana, I mean, not the electrician.)

Even when an average movie is made in Hollywood, where everyone concerned lives in comfort, by the end of the filming, the members of the company, especially the actors, tend to become edgy and splenetic. Amid the vicissitudes and the vortices of life in Vallarta and Mismaloya, it was only to be expected that the emotional difficulties would be compounded. When I left, the general sentiment was that anything could happen and probably would but that just possibly Huston was the one man in the world capable of coping. It was all his choice, and it must be that he knew what he was doing. I had the feeling he would pull it off in style, even though he was rather in the position of a man sauntering over a tract of TNT with a lighted cigarette in his hand.