The title Tampopo, which is Japanese for “dandelion,” is the name of a fortyish widow (Nobuko Miyamoto) who is trying to make a go of the run-down noodle shop on the outskirts of Tokyo that her late husband operated. The name—it’s the name that the restaurant acquires, too—fits her. She’s a weedy sort of flower—a meek, frazzled woman raising a young son and doing her best to please the customers. She can’t, though, because she’s a terrible cook, and knows it. One day, a courtly truck driver, Goro (Tsutomu Yamazaki), and his helper eat at the shop, and Goro, who wears a dark-brown cowboy hat straight across his brow, like the righteous hero of a solemn Western, gets into a fight on her behalf. Seeing him take on five men, she is inspired by his courage. She tells him that meeting him has made her want to be a real noodle cook, and, in his formal, majestic way, he makes it his mission to teach her.

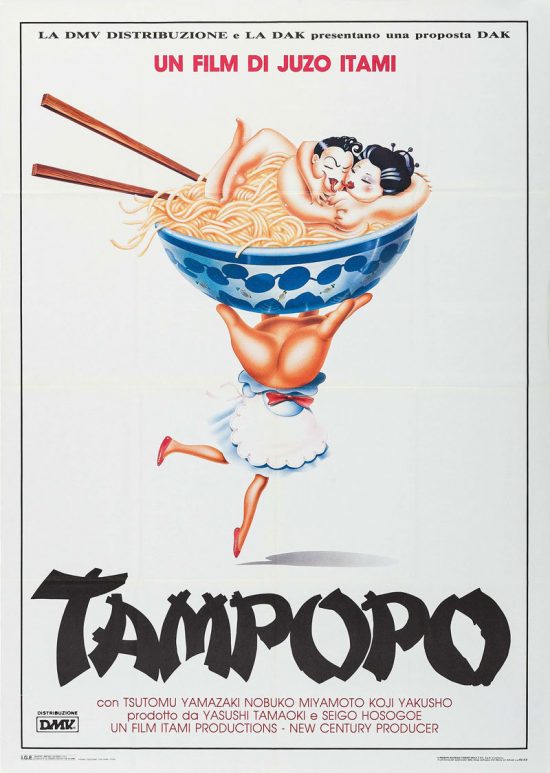

Juzo Itami, who wrote and directed this flapdoodle farce, is the son of a pioneer director. Born in 1933, he spent time as a commercial artist before becoming a well-known film actor (he played the bank-executive husband of the oldest sister in Kon Ichikawa’s The Makioka Sisters), and he’s also a popular essayist. He turned to directing in 1984 with The Funeral, a prize-winner in Japan, which also starred Nobuko Miyamoto (who is his wife). Tampopo, his second film, has its own brand of dippiness. The subtexts connect with viewers’ funnybones at different times, and part of the fun of the movie is listening to the sudden eruptions of giggles—it’s as if some kids were running around in the theatre tickling people.

The picture is made in a free form, crosscutting between two sets of food adventurers. The main story is that of Tampopo, the cowboy-samurai Goro, and their band of friends as they penetrate the secrets of other noodle shops, bribing and finagling to get hold of valuable recipes. The secondary story takes up the culinary-erotic obsessions of a pair of lovers: a gangster (Koji Yakusho), in a white hat and suit, and his ready-for-everything cutie (Fukumi Kuroda). These two demonstrate that eating and sex can be the same thing. The proof is in the orgasmic moment when they pass a raw egg yolk back and forth from his mouth to hers, over and over, until it bursts and dribbles down her chin. This is undoubtedly one of the funniest scenes of carnal intercourse ever filmed, and it’s shot in hot, bright color that suggests a neon fusion of urban night life and movie madness.

Itami uses his background in commercial art: every now and then, the characters assume shiny Pop poses, and the images have the slightly crazed look of heightened reality. (It’s a little like the heightening in Blue Velvet.) The whole movie—an understated burlesque of Westerns, samurai epics, and gangster films—is constructed like a comic essay, with random frivolous touches. (Goro wears his hat in the bathtub, like Dean Martin in Some Came Running, and it works on its own—it’s entertaining.) The characters are agreeable monomaniacs: they often speak in the stiltedly civilized language of food critics. (A noodle may be profound or synergetic; it may have depth without substance.) Itami loves filmed anecdotes. He shows us a woman dying just as her kids have sat down at the table, and her husband telling them excitedly, “Keep on eating! It’s the last meal Mom cooked! Eat, eat while it’s hot!” The scene is a brief sacramental black comedy. On the rosier side, there’s a disconsolate little boy whose parents have decreed that when he’s out playing he must wear the sign “I only eat natural foods. Do not give me sweets or snacks.” When a man gives him an ice-cream cone, you get the feeling that the man wants to spite the parents more than he wants to give pleasure to the child. And there are such diversions as a restaurant scene with a class of young ladies being instructed in how to eat spaghetti without slurping. Elsewhere in the restaurant—in a private room—the man in the white suit is supping on crawfish in cognac, from his cutie’s navel.

He’s as proud of the refurbished restaurant, Tampopo Noodles, as he would be if he’d saved a medieval village.

The film dawdles at times, and it has its lapses: Goro gives Tampopo her cooking lessons to the accompaniment of too much triumphal music; later, the jocular use of ragtime is a bit of a pain. And when Goro is giving Tampopo her workouts, to toughen her up for cooking, the spoof of Rocky is cloddish. But the lapses don’t last long, and the picture has a frisky texture. Reminiscences of Shane and Pépé le Moko and Kurosawa’s Yojimbo and films by Godard, Sacha Guitry, John Ford, and Sergio Leone may slip in and out of your consciousness while Tampopo struggles to get the broth right and goes to visit the Old Master, a chef who is surrounded by shaggy-haired vagrants discussing French food and wine. The Old Master decides to rally to Tampopo’s cause, and his gourmet bums (they’re like Japanese Hell’s Angels) sing him on his way. When the skinny-necked, fine-featured Master joins up with Tampopo’s other noodle warriors, the image seems posed as if for a calendar.

The film’s greatest charm is in Juzo Itami’s delicate sense of fatuity. He may have developed it during his years of acting. (He was in the American films 55 Days at Peking and Lord Jim as well as in Ichikawa films and, more recently, The Family Game, by Yoshimitsu Morita.) Tampopo, who seems to transform from within, like the American heroines of the thirties, weeps for joy when her band of friends and teachers pronounces her cooking perfection. Goro lives by his code, and he beams with satisfaction at a task accomplished. He’s as proud of the refurbished restaurant, Tampopo Noodles, as he would be if he’d saved a medieval village. He looks at the throng of customers waiting to get in and knows he’s no longer needed. Stately as ever, he heads out to his truck; the Old Master gets on his bicycle; and the whole group of mother’s helpers disbands.

Itami’s movie background is a satirist’s treasure trove. There’s a startling scene in which the white-suited sensualist buys a huge oyster from a woman diver; he tries to swallow it right out of the shell to which it’s still attached and it bites him on the lip. Stirred by his appetite, the diver feeds the rambunctious oyster to him out of her palm, then licks the blood off his mouth. The gangster—the movie’s dream hero—comes to the classic gangster finish. But even after he’s shot down in the streets on a rainy night and his loyal moll pleads “Don’t die!” he won’t stop talking about what he wants to eat. He’s got a recipe for wild boar stuffed with yam… And, with the whole history of movies reverberating in her voice, the moll says, “We’ll eat wild boars in winter,” as the gangster relinquishes his white fedora and puts it on her perfectly beautiful head.

[Photo Credit: AB]