Paris

So here we are, a couple of American women lunching at the restaurant of Guy Savoy, two stars in the Michelin, four toques in the fervidly celebratory Guide Gault-Millau. Naturally, in keeping with local custom, we eat sumptuously and talk about food.

Madame Savoy stops by to greet Patricia Wells. Later, Monsieur Savoy himself will emerge from the kitchen, a smallish, sunny man whose face lights up when Wells tells him without exaggeration that the meal has been “superbe.”

She is, of course, known to the house. By now, she also is known to large sectors of a national population obsessively concerned with pleasures of the table. Wells is a genuine phenomenon, an American and a woman who suddenly occupies a stellar position as a critic in a trade dominated by French males.

One night in June, she arrived home from a two-day media tour of the Netherlands to an uncharacteristic greeting form her husband, Walter Wells, news editor of the International Herald Tribune: “Sit down, I’ve got something to tell you.”

Expecting the worst, Ms. Wells obeyed.

“L’Express,” he told her, “wants you to be its restaurant critic.”

It was late, she was groggy with fatigue. “I’m too tired for that kind of talk,” she grumbled.

Her husband wasn’t kidding. France’s premier weekly newsmagazine, which had not had a food critic for some years, had called to ask her to fill the gap. In one afternoon, she settled on a pleasing salary and got assurances that she would be able to write without interference about any place in any town that took her fancy.

The weekly column, Mes Étapes Gourmandes, began early last month. As yet, there has been no visible response from her colleagues, and Wells expects no huzzahs. As she notes with cheer, the dominant emotion among her colleagues, other than a passion for eating, is “tremendous jealousy.”

“I can fill a restaurant, but I can’t empty it.”

She pauses to order drinks. The bottled water can be had at room temperature or chilled. The Sauvigny-les-Beaune is offered in a bucket of water precisely matching cellar temperature. Later, when the time for coffee arrives, we will have a choice of pure Colombian or a mix of Latin American beans. There is hardly anything a temple of gastronomy will not do to enhance the joy of eating. A few weeks earlier, Wells was dining at that holiest of holies, the three-starred Taillevent, when a friend asked to borrow Walter Wells’s eyeglasses in order to read the label on a bottle. In a trice, the waiter was at her elbow bearing a tray of spectacles in a dozen different strengths.

Patricia and Walter Wells came here eight years ago. They had met and married as colleagues at The New York Times, and she gave up her job as a food writer when he was offered the IHT post. In Paris, she settled in to freelance, writing two food columns a month for the Trib, turning out features for the Times’s Sunday sections, and pursuing research for what would be two splendid books on eating here: The Food Lover’s Guide to Paris and The Food Lover’s Guide to France.

Wells pauses in her narrative as food arrives and arrives and arrives. In addition to the dishes we have ordered, the chef sends out little tastes, small, savory bites of whatever is being cooked for other diners. Nothing can be faulted. If it could, Wells wouldn’t hesitate to say so. She eats at Guy Savoy often because it is near her apartment, and she complained for months about the inferior quality of the bread. Finally, she wrote about it in her IHT column. The bread, a fine, chewy sourdough, is now terrific.

Talk about power—but, of course, food critics would rather not. Wells will instead quote Christian Millau, who now heads the immense Gault-Millau food-guide empire: “I can fill a restaurant, but I can’t empty it.” This is contrary to the American experience, where a bad review is apt to be followed by empty tables.

She is an almost prototypical Midwesterner, a child of Milwaukee, rosy, warm, open and capable of immediate rapport in two languages.

The Wells guides are similarly structured. Her design had been to demystify French food for the visitor. Toward that end, she not only wrote about good or interesting restaurants, she also reported on specialty shops, markets and food fairs, and produced shapely little essays on such serious matters as tarte tatin, Camembert and choucroute.

The French edition of the France guide appeared this spring and was an instant success; it turned out that the natives could also learn from this foreigner. One journalist told her, “Do you realize how embarrassed we are that all this information was there and you had to come and show us?”

The notices were splendid, although there were occasional complaints about Wells’s high level of enthusiasm. She can’t help it. She is an almost prototypical Midwesterner, a child of Milwaukee, rosy, warm, open and capable of immediate rapport in two languages.

Media coverage for the book approached saturation levels. Most significantly, Wells appeared on “l’Apostrophe,” French television’s immensely popular prime-time book program, exposure that guaranteed her wide recognition. So, too, did her picture in her column in L’Express. But anonymity, a fetish among American restaurant critics, is a more complicated matter in France.

“French critics announce themselves,” Wells says.

Wells tries to maintain it. Reviewing a new place and anxious to insure that she will not have special treatment, she usually dines under a pseudonym or a friend’s name. This is not local custom. “French critics announce themselves,” Wells says. She does not; even if she looks vaguely familiar, she feels most restaurant owners are unlikely to realize who she is simply because she has not told them.

Of course, she has interviewed some of the most important chefs in France. In her view of her work, it is indispensable to talk to these greatly inventive, intelligent masters of the kitchen. On later visits, problems about the bill may arise. It is said that French critics do not pay for their meals. Wells doesn’t allow that kind of hospitality. “If I don’t pay,” she used to tell restaurateurs, “I can’t write about you.” After a few years, her hosts apparently had grown so fond of her that they were willing to suffer the consequences. The new formulation is: “If I don’t pay, I can’t write. If I can’t write, you’re taking away my livelihood.” That the French can understand.

We are now cowering before an onslaught of desserts: slivers of raspberry tart, tiny chocolate things, a shower of petits fours. This reminds Wells that perhaps the ultimate compliment to her book came from Gaston Lenotre, France’s supreme pastry chef. He called one day to thank her for “the best vacation I ever had.” When she met him for lunch at his restaurant, Le Pré Catelan, he showed her his copy, bristling with yellow marks, and he proposed a collaboration.

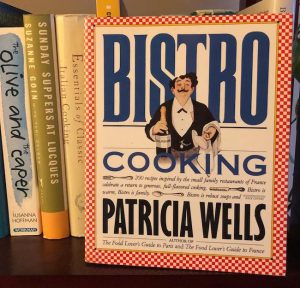

Wells’s plate of work is already brimming. For the past eighteen months, she has been testing recipes for a nearly completed collection of bistro fare gathered from places all over the country. Now, she has begun working with Joel Robuchon, widely regarded as the country’s most talented young chef. They have been friends since she reported some years ago, well before anyone else, that he was clearly France’s next three-star restaurateur.

Their book will carry complicated recipes of haute cuisine as well as sections on light, easy cooking. Wells launched the research last month by watching Robuchon work in the kitchen. As usual, she was a fount of enthusiasm. It was, she reported, like finally getting her Ph.D. in food.