The common canard is that New Yorkers are without heart, but as one watches the public agonize over the impending demise of Radio City Music Hall, there is evidence our denizens throb with the fervor of a newly minted social worker.

Politicians, journalists, movie critics, and social movers and shakers have formed a loud chorus (considering the subject, it should be accompanied by an organ) to save real estate in Rockefeller Center. Since politicians and landlords always have played in backroom duets, their roles are easy to define. But what of the others? Why are the same voices that delivered Bronx cheers to Lockheed now crusading to bail out posh private enterprise?

Is it their overwhelming love for the Music Hall? It’s odds-on that these people, like most adult New Yorkers, haven’t been inside the Music Hall in at least a decade, except on occasions of child-custodial weekends (proving once again that the liberated lifestyle is darker than anyone imagined).

But Radio City as an anachronism date back, in my experience, to the early ’50s, when, as a truant from the desks of William E. Grady High School in Brooklyn, I was one of Broadway’s foremost naïfs on the aisle.

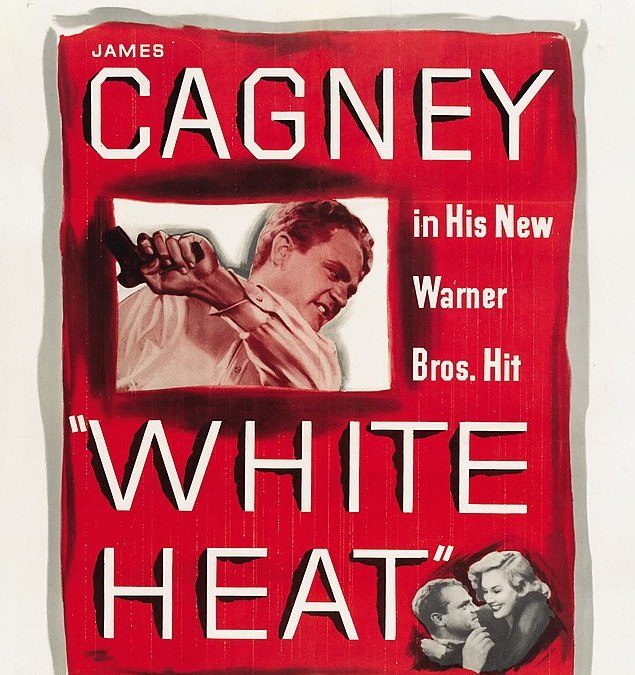

My boyhood buddy, Joe O’Donnell, and I saw so many movies during this period we held critical status with neighborhood contemporaries. Before they would plunk down their change at the cashier, they sought out our opinions on the available fare. Brought up on the Daily News (Times readers in our neighborhood were restricted to those who held “junior trainee,” i.e., ethnic-flunky, slots in brokerage houses), we rated movies by stars. Bogey, Cagney, and Ava Gardner flicks got the high four stars, while we heaped disdain upon Rory Calhoun, Edmund Purdom, and June Allyson (who needed another virgin?). But the sweet part about our aisle-sitting was that we rarely paid.

Joe’s older brother Tommy was a legendary force in our lives. A true Brooklyn exotic who read Marx, O’Neill, and the writers of the ’20s, he also claimed to be an atheist, which we perceived as dire, more so than missing your Easter duty. The kicker to all this was that he ran with a Broadway crowd that daily and nightly crashed movies. Not that Andy Hardy crap of running past a doorman, but with intricate blueprints to arcane access. Tommy (or “Bimbo,” as he was sometimes called) was the Rififi of the Rialto.

Tommy palled with my older brother, Billy. We all lived in the same two-family house in Brooklyn, with the O’Donnell’s upstairs. I never knew about the movie crashing till one night when I was awakened by a thud on the backyard cellar door. I soon learned the teenage Tommy’s standard M.O. He would steal from his bed, dress, drop out the upstairs window to the backyard, angle through neighboring yards, and exit on the street to head for the Great White Way. When he returned at three or four in the morning, he would, with the aid of a fence and drainpipe, climb back into his window. Just the kind of fantasy James Barrie would have written if he’d been Brooklyn-born.

To get into the Globe, we slide down a laundry chute into a back alley. For the Mayfair, we went to the roof via a dime-a-dance joint next door and once again descended a backstage ladder.

My brother occasionally went off with him on these nocturnal benders. Billy would dress in his one-button roll suit avec tie, and Tommy in his dungarees and Windbreaker. Because of their wardrobes, they became known as “Hollywood Harry” and “Broadway Sam.” These wardrobes were prophetic. Billy became a dapperish plain-clothesman for the NYPD, and Tommy a freelance writer under the nom de plume Fritz Dugan—Fritz after the local deli owner, and Dugan after the baker of his favorite cupcakes.

They broke Joe and me in locally at the RKO Kenmore. To crash the Kenmore, one had to climb a fire escape to the roof, then enter the roof exit door. That was easy. The next step was to descend a 150-foot backstage ladder in the dark, with the soundtrack from the screen blaring at. You in the void. While we clung to the ladder in fright, inching our way down, we heard a whoosh! Tommy, equipped with leather gloves, slid down a rope hanging from the rafters—putting him forever in a league with the Claude Rains of The Phantom of the Opera.

Under his tutelage, we graduated to Broadway. To get into the Globe, we slide down a laundry chute into a back alley. For the Mayfair, we went to the roof via a dime-a-dance joint next door and once again descended a backstage ladder. The Loew’s State was another roof caper. Here, we were spotted one day, and the cops moved in. Looking down on Broadway from a couple of hundred feet, hemmed in by the fuzz below, we shared the orgiastic fervor of Cagney’s Cody Jarrett atop the world.

Our favorite crash was the Paramount, that great house that for a movie and stage show cost 55 cents before noon. Here, one saw the famous singers and comedians—Tony Bennett, the Mills Brothers, the Four Aces, Johnny Ray, Teresa Brewer, Kay Starr, Fat Jack Leonard, Bob Hope, Jack Carter, and the great mock magician, Mister Ballantine, who used to stride arrogantly onto the stage to meager applause and ask, “Who the fuck did you expect—Houdini?”

To “break” the Paramount, one went into Walgreen’s next door and forced open a dire door into an alley that adjoined the movie house. In the alley were the emergency-exit doors of the Paramount, waiting to be popped. This was a standard way of crashing many houses.

But Tommy added a wrinkle. He carried a longshore hook to pry the doors. Indeed he had the dedication of a general: Once, when one of his charges had a loss of nerve, he cracked him across the face to bring him around. George Patton tried the same disciplinary device in the European Theater.

Over a two-year period, we kept active in this subculture. And we weren’t alone. Other neighborhoods were amply represented by their own heroes. One was the legendary “Spook,” who dressed completely in white down to his sneakers and always separated himself from his group till the movie was over.

We saw eight vaudeville acts with each show at the Palace, stage and screen shows at the Paramount, Roxy, and Capitol; at premieres, we shook hands with Victor McLaglen, Mauren O’Hara, and Aldo Ray; and we rarely missed an opening day. I had a personal high of scoring five houses in one day. That a headache and racking nausea followed was only fitting for such a campaign.

Each gang had its piece of the balcony, like Roman legions, encamping in the hills. No nonsense was tolerated.

But the Paramount was Mecca. The balcony was staked out by street gangs from around the city and their bubble-gum-snapping concubines. Each gang had its piece of the balcony, like Roman legions, encamping in the hills. No nonsense was tolerated. When Eddie Fisher, fresh from his “overseas” tenure at Fort Dix, Jersey, sang a bit of hokum called “I Can’t Get Used to This Change in Uniform,” someone threw a combat boot at him from the audience.

And there were the gaudy appointments of those halcyon days. While we bedecked ourselves with pistol-pocket pants and Billy Eckstine shirts, the Rivoli, in honor of the opening of De Mille’s Samson and Delilah, built a façade of a pagan temple over the front of the theater. The movie starred Victor Mature and Hedy Lamarr, a pairing which moved Groucho Marx to say that he wouldn’t go see a movie in which the male lead had bigger breasts than the female.

Though we didn’t have, or need, art houses to tell us John Ford, Carol Reed, Bogey, and the Marx Brothers were special, in our own way we were furthering our education. We learned economics and declamation in this way. Certain houses ran money-back offers for disgruntled patrons. After a clandestine entrance, one would bum a ticket from a paying patron and proceed to watch the show. Then one would seek out the manager and, ticket in hand, deliver a discourse on the inanity of the film and demanded his money back. Our performances ran hot and cold, but they were pressure-packed, unlike those at love-feast New School film seminars.

But in all this time, nobody bothered with Rady City. It played pretentiously uplifting cinematic versions of Pearl Buck novels or wholesome family fare—which meant nobody’s old man paraded around in his drawers—to audiences of marshalled school classes and ladies who resembled Artur Godfrey groupies.

The stage shows, with their marzipan Nativities and Resurrections, didn’t speak to us street infidels. The Rockettes were Midwest cheerleaders, and once you’ve seen a coordinated centipede, where is the ongoing intrigue? And, Christ, their idea of a comic was a putz with a Pinky Lee hat and a terrier.

To subsidize Radio City would be like funding a haven for the yokel outlanders who are now trying to bury us in Congress. I wish the claque clamoring for funding would admit to how many times they have patronized the Music Hall in the last twenty years. Are they closest Dean Jones and Herbie the Volkswagen fans?

And spare me the Art Deco décor. I live in the Village. Dow here, even the garages are high camp.

As has become our wont, New Yorkers are making the wrong fight at the wrong time. Where the hell were these voices when it was high noon for the Paramount?

[Image Via Wikimedia Commons]