The out-of-work mechanic with the beer gut, and the four turquoise rings, and the Gene Autry (pink and lime green) cowboy shirt with real pearl buttons, and the mutton chops, and the straight-back greased-down hair, and the big rhinestone belt, is stomping his heels and pounding his motor-oiled ham hock on the bench. “Bring on Jerry Jeff. Jerry Jeff. Jerry Jeff. Play ‘Redneck Mother,’ Jerry Jeff!”

The object of all this frenzy is Jerry Jeff Walker, a late-thirties, ex-folkie artist turned progressive country rocker. Up on the big stage here at Armadillo World Headquarters in Austin, Texas, Walker is twice as drunk, twice as wild, and twice as “cowboy” as his audience. He has a dark beard, a cowboy shirt that hangs out to conceal his growing beer gut, a big ten-gallon hat, and National Saddlery boots (hand-stitched by Charley Dunn). In his hands he holds a guitar. He stands perfectly still, raises his arm and smiles like a goofy, tranquilized cow, and the 4,800 people at Armadillo World Headquarters go wild.

“‘Redneck Mother,’ Jerry Jeff.”

“Hi ho, buckaroos,” Jerry Jeff says, and the show is on.

He is weaving and bobbing and staggering about, stoned on coke, grass, and uppers, but he’s still sober enough to belt out Ray Wylie Hubbard’s country-rocker classic “Up Against the Wall Redneck,” popularly known as “Redneck Mother.”

So it’s up against the wall redneck mother

Mother who has raised her son so well

He’s thirty-four and drinking in a honky-tonk

Just kicking hippies’ asses and raising hell.

On the word “hell,” the whole crazy audience of Austin shit-kickers, bikers, farmers, and graduate students throw off their cowboy hats, shriek and hoot, kick up their heels, and start in buck-dancing.

Jerry Jeff Walker smiles, his happy puppy grin again, takes another hit of Johnnie Walker, trips on the mike chord and falls backward over the cables. Oh, Christ, he’s out of it again. He’s going to fall through the drums like he did a couple of months ago at Castle Creek.

But not tonight. Not at the Armadillo! In the nick of time, Jerry Jeff rights himself and staggers, laughing, back to the mike.

“I’m rallying and fading, buckaroos,” he says, laughing.

The audience cheers wildly. They love him here in Texas. In Houston, Jerry Jeff and singer/songwriter Willie Nelson easily outdraw the Who. In Dallas, at Nelson’s Whiskey River Club, Nelson, David Allan Coe, or a visiting outlaw-country rocker like Tompall Glaser can sell out the house every night of the month.

But it’s Austin that all the new progressive country musicians really love. There are over four hundred bands in Austin right now, and the level of musicianship is both lyrically and musically sophisticated. The new country-rock may occasionally deal with the old country staples—divorce, the bottle, bad luck, and hard women—but it also confronts less provincial American themes, like the closing of the frontier and the coming of the machine age to a small Texas town.

All of this good news on the Austin scene started in the late ’60s when a number of singer/songwriters, mostly Texans who had moved to the big urban music centers like LA and Nashville, decided that they needed to get off of the commercial songwriting treadmill and go back to their own roots. So around 1968, many of these folks found their way back to Austin. And back to country.

In the early ’60s, these same musicians had scorned country music as ignorant and silly and hideous. If you were a young hip Texan, country was music for rednecks, something you wanted to get away from. It took the Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo and a little-known album by former Kingston Trio member John Stewart (California Bloodlines) to give ideas to the prodigal sons of Austin. Soon, musicians like Michael Murphey (best known for his songs “Geronimo’s Cadillac” and “Backsliders Wine”), wild folkie Jerry Jeff Walker, esoteric mountain musician Bobby Bridger, talking jive artist Steve Fromholz, and a host of others were experimenting with traditional country music tunes, but writing lyrics that expressed their own visions of things. The visions were more complex, ironic and articulate than those of the older, uneducated country musicians. These talented singer/songwriters then joined forces with local rock ’n’ roll musicians, fiddlers, and banjo pickers to start a new hybrid form. It was at once lyrical, topical, and personal, while retaining the hard-thumping, hard edge of rock ’n’ roll. During a typical performance of the Lost Gonzos, Jerry Jeff Walker’s current backup band, you could expect to hear a country beat, a jazz break, a tasty rock lick or two, some down-home fiddling, and all of it played faster and harder than mere country.

For several years Austin became a place where musicians could gather, learn, and cooperate. The scene was one in which, according to Austin musician Bobby Bridger, “personal growth and the music always took precedence over cash and success.”

In the late ’60s, Nelson moved to Austin. That may not sound like much, but in Nashville music circles it was considered tantamount to slitting your wrists and locking the bathroom door.

Perhaps the best example of a musician who found himself in Austin is that of middle-aged Nashville songwriter Willie Nelson. Nelson had been pumping out songs for other people for fifteen years and had made a pile of loot. Everyone from Johnny Cash to Perry Como had cut Nelson’s songs. Yet Nelson was a frustrated man. His own singing career had never progressed beyond a cult following, and he was sick to death of the business parties, the back-stabbing, and the hypocrisy of Nashville. So in the late ’60s, Nelson moved to Austin. That may not sound like much, but in Nashville music circles it was considered tantamount to slitting your wrists and locking the bathroom door. Nelson’s friends besieged him. He was making money. He was popular. Why had he grown his hair long? Why did he hang around with hippies and Commies? What would happen to him in Austin? Nelson, as uncertain as anyone, simply knew he could stand no more. “Nashville almost broke me,” he says now. “I had to go. No matter what.”

To his surprise, Nelson met scads of talented musicians in Austin who felt as he did. It wasn’t long before he had given up his Nashville-Bible salesman look for good and was seen smoking joints, wearing a red bandana around his forehead, drinking Lone Star beer, and eating nachos with the local crazies. Instead of fading away, his career boomed. He came out with new songs, new records. This past year he had his greatest hit ever, “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” and when Bob Dylan brought his Rolling Thunder Revue to Houston recently, Nelson played with them for a night. His subsequent album, Red Headed Stranger, has won all sorts of awards, including Best Country Album of the Year.

Nelson and the other Austin singers have become so popular that their very success has threatened the purity they sought. Music leader and Austin idol Michael Murphey recently left town, complaining that the scene had been taken over, like Nashville before it, by business freaks, record wheeler-dealers and hustling managers. Sure enough, calls flood into Moonhill Productions, Austin’s top booking agency, every day. But even though Moonhill handles some of Austin’s most popular artists (Rusty Wier, B. W. Stevenson, Denim, Asleep At The Wheel), there is a great deal of bitterness between the company and some of the Austin musicians who haven’t forgotten why they came back to Austin in the first place. “I don’t want to live in Music City, U.S.A.,” says Bobby Bridger. Moonhill is certainly not the only business enterprise to see dollar signs. Nashville singer Waylon Jennings, whose career was finally launched by picking up on the cowboy, Rough Rider image, wants to open a recording studio in Austin, and there are a dozen other people with similar ideas. (Right now, Austin has only one recording studio, Odyssey Studios.) And, of course, the media have not been slow to pick up on Austin either. Rolling Stone and Crawdaddy have been paying close attention, and just last month Qui magazine featured a rave article about the town.

The Austin pictured in the media, however, is one that many Austinites abhor. They feel that the “cosmic cowboy-outlaw” image that Walker, Nelson, Jennings, Murphey, David Allan Coe, and endless hordes of imitators are spreading is exactly what the town and its music don’t need.

“I can’t stand that stuff,” says Austin artist Jim Franklin. “I remember when Rusty Wier was a hippie who laughed at country music. Now he wears a cowboy hat, and in between his songs he tells stories about being out on the range or down in the barn. It’s embarrassing.”

Other critics of the scene see more serious implications. “It’s a bunch of crap, this cosmic cowboy bullshit,” says ex-Austinite country music singer/critic Dave Hickey. “They get up on the stage and come on like bad-asses. Most of these guys like Jerry Jeff Walker have never been near any real violence.”

Delbert McClinton, a terrifically talented rhythm and blues singer/piano player who has spent a lot of time in Austin, agrees. “You see all these cowboys singing about kicking hippies’ asses, and people like Edgar Allan Coe [McClinton’s name for David Allan Coe], who jumps off the stage screaming, ‘I can kick the shit out of any man in the bar,’ and it makes you want to get sick. I mean, I been playing honky-tonks all my life, and I’ve seen real violence, and there ain’t nothing cool about it. I saw one man rip another man’s stomach out with a beer bottle, and lemme tell you … it was about as far from cool as you can get. I don’t relate to this cowboy ass-kicking stuff. It’s cheap and it’s dangerous.”

Austin Comes to Nashville

If critics were becoming disillusioned by the pyrotechnics, the performers themselves were becoming disenchanted with the music environment in Austin. Even a diehard like Jerry Jeff Walker went back to Nashville to record his latest album.

A doper and rambler from Oneonta, New York, Walker had come to Austin in the late ’60s and found the perfect backup in the Lost Gonzo Band, a group of Texas rock musicians who were experimenting in the new country rock mode. In 1970 the group holed up in a little barn in Luckenbach, Texas, put up bales of hay for baffling, and spontaneously cut what many people still think is the best album to come out of progressive country: Viva Terlingua.

The album, fine as it was, promised even greater things for the Gonzos, and Jerry Jeff. It sold well over three hundred thousand copies, and it looked as though Redneck Rock was on its way to national launching. The next album, however, Walker’s Collectibles, was a major disappointment. The tunes were half done, and only a few, such as “The Last Showboat,” were really distinguished. Worse, the record sounded as though it had been produced in a wind tunnel.

In fact, it was this thicket of problems that brought Walker up from Austin to record his newest record with the expertise and consistency that only the studio musicians of Nashville can provide. Thus, it was in a darkened control room in Quadrophonic Studios in Nashville that I found the best-known Austin musicians. What’s more, they weren’t playing but sitting around in the booth and hallways, while the Nashville professional studio men did the larger burden of the work. The irony of all this was not lost on the Gonzos’ keyboard player, Kelly Dunn, who explained to me how Austin had come back to Nashville: “The first album, Viva, was just the perfect combination of all the right forces. Jerry Jeff was up. We had a casual outlook. It all happened by accident. On ‘London Homesick Blues,’ that crowd reaction you heard was all spontaneous. But on Collectibles … things fell apart. Jerry Jeff was out of it, got pissed off at himself and was like a bear … he drinks a bit, you know. He came into the studio shaky and stoned, and with the songs half learned, and in some cases half written. Oh, it was the worst!”

“Is that why Ridin’ High (Walker’s last album) was cut here at Nashville with studio musicians instead of Austin?”

Dunn nodded and looked downcast.

“Yeah, to be frank, it was sheer panic time. So he didn’t want to give Odyssey another chance. When you come up here and use the studio session men, you know exactly what kind of product you are going to get. Kenny Buttrey, Wendall Miner, Bobby Thompson, David Briggs, Johnny Gimble, and Norbert Putman have been playing together on so many sessions so long they have it down to a science.”

“How does it make you and the other boys feel to be shoved aside?”

Dunn shrugged, and sucked in on his joint. “How do you suppose it makes us feel? Kind of useless.”

Through the glass window I could see Jerry Jeff sitting on a stool, strumming his guitar. Around him were the Nashville Pros, the studio men who make over a hundred thousand dollars a year playing sessions. All of them are virtuoso performers, and the work they were doing this night was nothing short of superb. Walker had just finished cutting a tune called “Some Day I’ll Get Out of These Bars,” a sad, beautiful song about an old honk performer who knows he’ll never be a star. His pathetic refrain, “Some day I’ll get out/Some day I’ll get out,” had been handled with remarkable sensitivity by both Jerry Jeff and his sidemen. Yet, there was something missing. The song sounded almost too produced, the steel guitar seemed too prominent, too whiny in the grand old soap opera tradition of steel bathos. It was good, but it wasn’t the Austin sound at all. The energy and enthusiasm of the early records were missing.

During the break I walked out of the studio and into the crowded little dimly lit foyer, where the studio men refreshed themselves with Coke, cigarettes, and coffee. Kenny Buttrey, Nashville’s leading session drummer, was curled up in a chair:

“Same old thing,” he said glumly. “One, two, three, four. It gets dull as hell sometimes. I don’t know why they call this stuff progressive country. There’s nothing progressive about the beat. I was in a real progressive country band with David and Norbert, and some other people. We were called Area Code 615, and we mixed jazz with rock and bluegrass. We were really good but we were before our time, I guess. The country deejays wouldn’t play us because we were too funky, and the funky rock deejays wouldn’t play us because they said we were too country. Wheww!”

Buttrey shook his head and tapped lightly on the chair’s arm.

“I been playing sessions since I was fourteen. I’ve played with everybody, including Dylan. I played on Blonde on Blonde and Nashville Skyline.”

“How do you like playing this session?”

Buttrey shrugged his shoulders. “One, two, three, four,” he said.

The Outlaw’s Roost

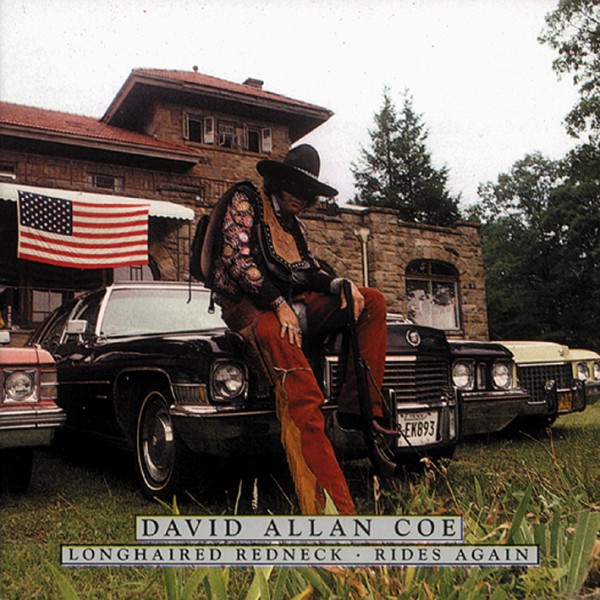

The image Jerry Jeff Walker, The Lost Gonzo Band, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, David Allan Coe, and countless other would-be stars from Austin (and Nashville) like to promote is that of the hard-riding, fun-loving, vaguely tragic, two-fisted cowboy. Jerry Jeff is a perennial good-time boy with flashes of sensitivity, while Waylon Jennings is a rugged but aging buckaroo who is often heartbroken but still fights the good fight. (If that sounds vague, it’s because it is. Pop images are carefully chosen to look like anything one wants them to be. Thus Jennings could either be a drunken sot who has lately cleaned up, a good man who has been wronged, or a tough-assed hillbilly with a heart of gold. Choose whichever cliché gets you through the night.) Willie Nelson is a late-blooming fatherly sort of hippie-cowboy with a beatific smile. David Allan Coe, with his rhinestone earrings on the one hand, and his ultimate machismo on the other, is an extreme example of both sides of the “sensitive ass-kicker” that all these “outlaws” romanticize and exploit.

For it is the Desperado, the Bandito, the Outlaw that is the common denominator for all the new cowboy-country singers. Not only do they dress like cowboys, but some of their most memorable work deals with the same timeless, romantic myths. Walker sings Guy Clark’s “Desperados,” which equates the love of a young boy for his father figure with the love of “two desperados waiting for a train.” Jennings sings “Slow Movin’ Outlaw,” a tune that tells us about an old cowboy who is being shut out of the Wild West (“Where does a slow movin’/Quick drawin’ outlaw/Have to go?”).

“As people feel more and more trapped in their lives in this country, with their dull lifeless jobs, boring family lives, and hopeless inflation, the music industry tantalizes them with these images of fake rebels to look at.”

And David Allen Coe simply sings of himself: “People all say that I’m an outlaw….”

It is the stuff that has made legends of the James Gang and the Daltons. It is the myth that made Sam Peckinpah a rich man. Though it’s corny and hokey, it’s also irresistibly American. Still, there is a dark side to all this posturing.

One young Austin singer had this to say about the outlaw image: “It’s just a lot of crummy jive. As people feel more and more trapped in their lives in this country, with their dull lifeless jobs, boring family lives, and hopeless inflation, the music industry tantalizes them with these images of fake rebels to look at.”

Similar sentiments were expressed to me by Neil Reshen. Known as “Mad Dog” for his negotiating toughness, Reshen manages Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings. In a telephone conversation I had with him, Reshen was quite candid about the “outlaw” bit:

“Shit,” he said. “You couldn’t find two guys who are less like outlaws than Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson. They are such homebodies that they will travel only on weekends. The rest of the time they like to be in their swimming pools with their families. It’s all a bunch of horseshit really. But if the public wants outlaws, we’ll give them outlaws.”

Sure enough, the new cowboy singers live in the plushest, tackiest bourgeois luxury. Jerry Jeff Walker, for example, lives in a beautiful sixty-five-thousand-dollar suburban-styled home outside of Austin, complete with modern kitchen, fireplace, sliding paneled doors, swimming pool, and basketball court.

In between takes at the studio, I asked Walker about his house.

“Yeah, I got all that, but I threw my color television set in the swimming pool.”

That one incident is reported again and again in article after article on Walker. The disparity between myth and reality was brought thumpingly home when I visited Walker and his friends at his suite in the Spence Manor, Nashville’s plushest hotel. Catering especially to rich country music stars and record company executives, the Spence Manor is very expensive; there are no “Rooms To Let, fifty cents” at the Spence, only exclusive three-room suites. Bums, transients, and desperados need not apply.

The night I joined a party in progress at the Walker suite, Jerry Jeff himself was still at the studio, but his friends, Texan Guy Clark (“Desperados,” “L.A. Freeway,” and now his first album, Old No. 1); his wife, Susannah Clark, also a budding songwriter; Dick Feller (“The Coin Machine”); Nashville songwriter Dave Loggins (who scored big last year with his hit record “Please Come to Boston”) and his wife; and TV and record star Jim Stafford (“Spiders and Snakes,” “Bill”) and his girlfriend, Debbie, were enjoying themselves snorting cocaine, smoking pot, taking speed, and drinking Jack Daniels.

“Let’s call room service and order a whole bunch of hors d’oeuvres,” Susan Walker said.

“Is M.C.A. paying for it?” Guy Clark asked.

“Right!” Susan said. “Of course.” She declined the cocaine but accepted a joint.

Guy Clark picked up the guitar and began to strum. Deborah looked over and stared at Clark sitting there half-poised to play.

“Oh … play ‘Desperados’ … please play ‘Desperados’….” Dick Feller, a short pudgy man, nodded seriously.

“Guy’s version is great,” he said. He then started to sweat a little and looked over at Susan Walker. “I mean … I like Guy’s and Jerry Jeff’s, of course … they’re different.”

Like everyone else, Feller cannot afford to alienate Walker, on whose albums he often plays. The session money is too good.

Susan Walker gave her Pepsodent uptown-Dallas smile and nodded her head. “Guy’s version is a monster,” she said.

“A monster,” said Dave Loggins.

Guy went into a rather ragged, coked-out version of the song, and in the chorus everyone joined in: “Like desperados waiting for a train.”

Even in the Spence Manor under the influence of booze, coke and dope, Clark made the song come alive.

At the song’s conclusion, everyone fell silent for a moment.

After the pause, Jim Stafford began explaining his musical aesthetic to me.

“Think Pop,” he said. “I have a sign that says ‘Think Pop’ on my office door.”

“Money, money, money,” Susan Walker said. “That’s the name of the game!”

“Makes the world go round,” David Loggins said. “Think Pop,” Jim Stafford said. “Say, who’s got the coke?”

David Allan Coe

Of all the new cowboy rockers to hit the scene, the fastest-rising and most infamous is David Allan Coe. His press release makes him sound like the Definitive Outlaw, and Coe himself has gone to pains to establish his identity as authentic. According to Coe himself, he “spent most of [his] life in institutions, orphanages, reform schools, and jails.” This career grande reached its zenith in the early ’60s, when Coe was supposedly arrested for burglary, put in Ohio State Prison, and there murdered a man. According to the legend, Coe then got out, receiving a pardon because no one knew he had committed the prison crime and because Johnny Cash heard his songs and intervened on his behalf

Coe came to Nashville in the late ’60s, bummed around the streets, hanging out with the Outlaws, a band of motorcyclists not unlike the Hell’s Angels. His first hit record was a single written for Tanya Tucker, the teenage recording star. The song was called “Would You Lay with Me in a Field of Stone,” and it proved that beneath the wild, ambitious, and unpredictable presence there was a real talent—sensitive, intelligent, even lyrical.

Coe, however, chose not to go the straight and narrow path—firmly establishing oneself as a songwriter, then cutting an album. He figured he could cut years off his apprenticeship by becoming the baddest, the meanest, the most dangerous outlaw of them all. Where Jerry Jeff was boyish, and Waylon and Willie Nelson were older and obviously playacting, Coe would be the real McCoy, a murderer! Soon he had a new act. David Allan Coe—The Mysterious Rhinestone Cowboy. He took to wearing rhinestone suits and black masks, which made him look like Zorro. Huge, ugly rhinestone earrings hung from his right ear. He’d show all those shit-kickers and Austin creeps who was a bad-ass! In gig after gig, Coe won publicity by challenging the audience to fight him, by mocking Waylon Jennings (“He’s just a greaser”) and by doing devastating imitations of Jerry Jeff’s goofy, friendly smile. Though traditional country fans despised him, Coe got his share of the young, hip audience who loved the new rock sound in country. And he also got another type of fan, the kind who cares nothing for the music but gets faint with excitement at the possibility of spilled blood.

I was sitting in the Exit Inn watching the last set of the David Allan Coe show. Tonight Coe was dressed relatively conservatively in a denim jacket, Levis, cowboy boots and a big black hat. The rhinestone in his ear shimmered in the night lights. Behind him his band of young Austin-Houston-Tennessee rockers were pouring out the hard-pounding, driving new country sound, while Coe sang his newest hit, “Long Haired Redneck.”

“People all say that I’m an outlaw,” he wailed.

On the word “outlaw” the entire front rows of people stood up at their tables, raised their glasses and bottles and screamed!

“You tell ’em, David. Outlaws, you tell ’em!!”

These enthusiastic fans were the Outlaws, Coe’s old motorcycle gang, and they were a terrifying if predictable sight. Leather jackets, beards, goggles, iron crosses … they stamped and screamed and pounded one another on the back.

Coe’s voice, hoarse and rather puny to begin with, could barely be heard over the incredible wailing of the guitars, the pounding of feet on the floor.

After his last song, Coe went through a side exit to the outside. He was staggering wildly, and the Outlaws all got on their head gear and trailed after him. I put on my jacket and walked out among the crowd of screeching bikes and screaming, drunken men.

“Gonna ride my hog over the hill. Gonna ride all the way to the mo-tel,” Coe shouted.

“You can’t ride, David,” a short Outlaw said, holding Coe around the middle to keep him from jumping on his big Harley.

“TAKE THE BUS TO THE MOTEL,” a fat, powerful-looking Outlaw yelled, his little red eyes burning like a mad razorback’s.

“Gonna ride my hog,” screamed Coe.

But he didn’t get on his bike. Instead, he half fell up the steps of his big bus, which had his name in foot-long black letters on the side.

I followed him on the bus and met a man who claimed to be a childhood friend of Coe’s. “David’s real drunk,” the man said. “But he’s not that drunk!”

“What do you mean?”

“Oh, he’s just putting on an act. He won’t really ride the hog to the motel. He just wants to let them talk him out of it.”

“I see. And did he really kill anyone?”

“Hey,” the guy said. “You’re a writer, aren’t you?”

There were Outlaws, about fifteen of them, sprawled around the room. I looked at their eyes, which were all trained right on my own. In the exact center of the group, like some ancient fertility god, David Allan Coe sprawled on a bed.

“Yeah.”

“Are you the guy who wrote the expose in Rolling Stone, the one that said David Allan wasn’t a murderer?”

“I never heard of that.”

“Good. I think a cunt wrote it, anyway. She said David Allan wasn’t a murderer at all, that he was only in on possession of burglary tools.”

Suddenly, the little Outlaw with the set jaw of a frothing dog sat down beside me.

“David’s a real outlaw,” he said, smacking his fist into his palm. “You a writer? You ought to come with us to the motel. You can ask him all about it.”

“Okay. Is he driving his hog?”

“No,” the little man said, hitting his fist into his palm again. “He’s going in his limo.”

The bus floated through the Nashville streets and stopped at the James Thompson Motor Inn. I got out and walked with Tommy (the Outlaw) and Coe’s old friend, Bobby.

“It’s on the fourth floor.”

We climbed the steps and walked down a long motel corridor. Looking over, I noticed it was a good seventy-five feet to the parking lot. At the door, Tommy waited for me.

“Come on in, writer.”

“Sure.”

I felt frightened by his tone-soft, but mocking. I had assumed that there would be women, other musicians, and whiskey. But there was none of that. Instead, there were Outlaws, about fifteen of them, sprawled around the room. I looked at their eyes, which were all trained right on my own. In the exact center of the group, like some ancient fertility god, David Allan Coe sprawled on a bed. On his lap was an ugly, trashed-out looking woman, who was laughing insanely.

Behind me the door snapped shut. “This here is the writer,” someone said in a steel-wire voice.

Everyone was totally silent.

“The writer who wrote that shit about David Allan not being an outlaw!” someone else said.

I felt my breath leaving me and tried to laugh it off. “Hey, c’mon, you guys. I didn’t write that stuff.”

A short, squat, powerful man, the same Outlaw I’d seen screaming at the Exit Inn, came toward me. “You wrote that shit, did you?”

He reached in his back pocket and pulled out a five-inch hunting knife.

“Hey, wait now,” I said.

He started flicking the blade at my jacket, my arms and my jaw.

“Stick him and throw him over,” someone yelled.

“Got to stick the writer,” said a long, bony-looking man with a broken nose and space goggles.

I looked at Coe for assistance. A dull, cruel smile passed across his face. He said nothing.

“Put the knife down,” a voice said.

I turned and saw a big, bearded man coming out of the adjoining room. “Everyone cool it,” he said.

The man took my arm and guided me into the back room.

“I’m David Allan’s brother,” he said. “I jes want you to know that it ain’t like this most of the time. It’s jes that the boys are a little sticky about the Rolling Stone article. If you’re gonna write something, you be sure and correct that shit now, heh? David Allan has been in institutions all his life. He’s an ex-murderer and a real outlaw. He ain’t like a lot of these phonies, ya know?”

“Yeah,” I said. “I got the picture.”

Waylon Jennings

Of all the singers in the new country scene, Waylon Jennings easily has the best voice. For years he had recorded at RCA under Chet Atkins’s supervision, and for years everyone in Nashville thought he would be the star to make the big crossover into the all-important Pop Market. It never happened. Instead, Jennings’s albums (seven of them) were marred by the very thing that had sent so many excellent singer/songwriters packing off to Austin. Instead of emphasizing Jennings’ rich Texas voice, his incredible phrasing and texture, the albums were strictly one-shot, treadmill productions. No matter that a song would be better with a lone steel guitar or a simple rock lead. At Nashville RCA, everything was turned out in the same dull fashion.

It wasn’t until Jennings left Nashville RCA and cut Honky Tonk Heroes, an album entirely written by Texan Billy Joe Shaver, that he finally really made use of his greatest asset: his voice. Stark, simple, and full of longing for the past, the album is a classic of progressive country. Songs like “Honky Tonk Heroes,” “Slow Movin’ Outlaw” and “Rose of a Different Name” come at the listener unencumbered with girl choruses, violins, and foul-sounding Al Caiola Romantic Guitars. Interestingly enough, it was on Honky Tonk Heroes that Jennings changed his image. Up till then he had been a slick-backed, clean-cut country boy who posed staring off moodily into the sun. On Honky Tonk Heroes a new Jennings emerged—The “Outlaw” Waylon Jennings. Complete with beard and black shirt with white pearl buttons, he posed at a glass-strewn table with his band and the three-fingered Billy Joe Shaver. Since that time Jennings has become one of the most popular acts in the country. Right now, his new anthology album, Outlaws, is riding high on the country and pop charts. The album features a wanted poster on the front and pictures of Jennings; his wife, singer Jessi Colter; Willie Nelson; and Tompall Glaser, whose own band is called … The Outlaws!

I met Waylon Jennings at his huge, walnut-paneled office at Glaser Brothers Studios in Nashville. A large, powerful man with deep creases in his face and wide, sensitive eyes, he exudes old-fashioned John Wayne-variety manliness.

As we began to talk, Jennings’s secretary came in and gave him a plaque. He had won yet another award as Best Male Singer of the Year.

“Put it somewhere,” Jennings laughed. He sat down behind his walnut desk. There were three phones on it, and every couple of minutes they lit up. I couldn’t help but think of the incongruity of a man who sings of the last trains and the last gun fights, sitting behind a desk with three white phones and ten red hold buttons on them.

“How do you feel being a cowboy on the one hand and a businessman on the other?”

Jennings shook his head.

“I used ta not like it, but hell, Hoss, if I don’t take care of business I’d still be out making those turkeys for Chet. You see, I had to become a businessman or I wouldn’t have survived. I been on the road since Kitty Wells was a Girl Scout! I did three hundred days a year on the road for eleven years. On pills … I was being destroyed.”

“What’s all this outlaw stuff now? Isn’t it being over-killed?” Jennings struck a thoughtful pose.

“Yeah, I suppose it is. I don’t know where it comes from. I think the fans gave it to me. I was the first outlaw, you know.”

“I thought Jerry Jeff Walker was.”

“Hell no,” Jennings said. “I was the first to buck Nashville … not that I have anything against those boys. They just don’t ask the artist what he thinks. No, Walker picked up on it after me … but you know what?”

Jennings leaned across his desk and peered at me with hugely earnest eyes.

“He never has made it. You know that, doncha?”

“What of David Allan Coe?” I related my story of the knife threats.

“Well, that beats all,” Jennings said. “He’s crazy. He thinks he’s bucking the system, but the test is whether you can play what you want or what they tell you to play. I have control over my life.”

Suddenly Jennings looked startled and asked what day it was. I told him the date.

“Oh, God. I missed Valentine’s Day. I got to call Jessi and get her some flowers and candy.” A second later Jennings was on the phone with his wife.

“Hello, darling….Yes, I love you and I’m sorry I missed Valentines Day….”

The Promised Land

“The thing is we might have reached a saturation point with the cowboy-outlaw bit around here, but nationally it’s still an open ball park.”

The speaker is Tom White, a pale-faced, balding young man who introduced himself as the publisher for many of the best new Austin groups and single acts—acts like Steve Fromholz, Rusty Wier, B. W. Stevenson, Denim, and Asleep At The Wheel. The location is Moonhill Productions, Austin’s only major booking agency.

“Do you think of the music as an art form?”

White smiled and shook his head. “No. I tell all my people to think hits.”

He got up from his office desk and walked over to a tape machine.

“Music is capitalism,” he said. “When I was in college and all this outlaw rock scene was just starting around here, it was true that people wanted to get away from it all. And it was also true that people felt that country-rock was maybe gonna be the next art form. I used to think that Jerry Jeff Walker and Michael Murphey and Willie Nelson might be the Hemingways and Faulkners of our generation. But it’s not true. The form is too limited. It’s something like a commercial. You can get startling effects, but they don’t last … they can’t be built on, only repeated, with minor variations … so, practically, I think that it’s a shit heap. Right now, Moonhill Productions is on top of the heap, but basically it’s all still shit.”

“But some people, like Walker and Nelson, really have done remarkable things with the music.”

Tom White shook his head. “Yeah, that’s what amazes you. As crummy and corny as it all is… all this outlaw business … there still is good work being done in the form.”

I said goodbye to Tom White and made my way out through the office. On the wall were pictures of Rusty Wier in a cowboy hat and beard, Steve Fromholz in a cowboy hat and beard, B. W Stevenson in a cowboy hat and beard.

“The second generation of Redneck Rock?”

“Yeah,” Tom White said.

Bobby Bridger

Bobby Bridger is a thirty-two-year-old Austinite who left Nashville in 1968. He came to Austin because of the dream, that it was a place where a man’s talents wouldn’t be wasted, where he wouldn’t be run to death.

At El Rancho Restaurant, he drank a Carta Blanca and shook his head.

“Tom White … Moonhill … they say the forms are no good, but the forms are fine … fine … if they would just leave them alone! Let them be. But the worst thing is what the musicians themselves have done. The term ‘outlaw’ is now anathema to me. At first, it was fun, maybe it even meant something, but now it’s become a completely synthetic term. You’re an outlaw if you wear a cowboy hat and a couple of turquoise rings. I don’t call those creeps ‘outlaws,’ I call them Cowboy Babbitts.”

“Originally country-rock united the two cultures, hillbillies and hippies. That was when it was good. Now they are trying to turn it into this big macho American John Wayne trip. It’s Nashville all over again.”

“Aren’t you tempted to make it yourself?”

“No! I was doing well at Nashville in the ’60s for Monument Records, but I came here to be somebody different… we all did. But in seven years, I’ve seen most people bitten with the success bug. It’s not just a few people … it’s most of them. A few aren’t. Willis Ramsey and Townes Van … Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson … they are both good musicians, but instead of finding their own way, too many of the younger kids are jumping on their bandwagon.”

“What should they be doing?”

“Finding their own voice,” Bridger said, shaking his head. “I don’t like Jerry Jeff personally, but I’ll say this. He is his own man. His songs reflect his personality. Now people like Rusty Wier and the younger crowd … their music reflects a commercial myth….I mean originally country-rock united the two cultures, hillbillies and hippies. That was when it was good. Now they are trying to turn it into this big macho American John Wayne trip. It’s Nashville all over again. Real talent gets devoured, reshaped, remolded … all for the sake of money.”

As we finished eating, Bridger told me how he was still hanging on, living cheaply out in the woods in a place called Comanche Trail. Later, we sat in my hotel room and listened to a tape Bridger had brought with him. A startling original work called Jim Bridger and the Seekers of the Fleece, the form is a country-epic. Chapters of spoken rhymed couplets are alternated with songs about a real mountain man, Jim Bridger (Bobby Bridger researched his life for three years). The actor Slim Pickens, a close friend of Bridger’s and an amateur historian, reads the oral poetry. Bridger himself sings and he is backed up by the Lost Gonzos. The tape lasts for an hour. The story, though familiar, is compelling. Jim Bridger, a tough mountain man, a pioneer, goes west to find the new good place. He finds his Eden in the mountains, marries an Indian girl, but gets sucked into expansionist business schemes. In an attempt to “expand,” he loses his world. I listened and was deeply moved. Bobby Bridger picked up the tape and smiled.

“Well,” he said. “I guess you can see why I wanted you to hear that!”

“Yeah.”

“That’s what’s happening now with the country-rock scene and to Austin. It’s new, brand new, and there’s a lot of energy. So much talent. But everything is moving too fast… people aren’t thinking.”

He put on his coat, and we shook hands.

“I love Austin,” he said. “And I would hate to see the day when they come in here and do a movie about the place.”

“You mean like Nashville?”

“Yeah,” he said. “Like that.”

Postscript

Not counting Larry Flynt, the first piece I ever wrote on entertainers was Redneck Rock, and as you have now seen, it was an assignment which nearly got me killed. Not for the first time, either, but this time was very “hands-on,” trust me. The Geneva police had scared me and then humiliated me, Larry Flynt’s brother Jimmy threatened to kill me with a ball-bat, and even LeRoy Neiman came up to the New Times’ offices in search of me, when my less than polite piece on him came out. Needless to say I am pretty sure Reggie would like to punch me out, as well.

But up until the time I went down to do my piece on the phenomenon of redneck rock no one had actually pulled a hunting knife on me before.

That, Dear Reader, was some scary shit. And here’s what happened after the knife almost pierced my ribs.

After I survived the unpleasant little scene with David Allan Coe and his pals, I made it back to my room at the Spence Motel and called my editor at New Times, Jon Larsen. I was wired up to my teeth by almost being stabbed and thrown off the motel roof and I guess I was pretty wound up on the phone:

“Jon,” I said, breathlessly. “You can’t fucking believe what just happened on this story.”

I then riffed through the whole crazy experience, all the while fingering my leather jacket where the hunting knife had sliced it into frazzled tassels.

“Man,” I said, winding up my tale of heroic survival against an outlaw gang, “Those fuckers almost killed me!”

There was a long silence on Larsen’s end. I waited, thinking he was probably feeling pretty bad that he had sent me down here, where I had almost bought the farm. I half expected him to say, “Man, that is really too bad, Bobby. I am so glad you made it, buddy.”

But he had other things on his mind:

“Let me ask you this, Bob,” he said in a kind of reflective and slightly quizzical voice: “Did the Outlaws knife actually cut through your leather jacket and into your flesh?”

“Huh?” I said. I was stunned.

“I mean were you actually stabbed? Any blood, Bob?”

“No,” I finally said. “But it reduced the arm of my jacket to tattered strips of leather.”

Another long silence. Then in a really irritable voice:

“Yeah, I know that Bob, but if the knife had actually cut you we could have had a much more promotable story. We might even make the network news. As it is … with just the jacket sliced … well, you see my problem. We can’t really promote that.”

As the old saying goes down on the docks in Baltimore, when I heard that I didn’t know whether to shit or go blind. The whole scene had been surreal anyway, but Larsen’s reaction was the coup de grace. I couldn’t believe it. I started yelling in the phone:

“Well, gee, Jon, I am really fucking sorry, okay? I mean really, man, if I had thought this thing through a little better when the fucking guy took the knife out I would have OFFERED HIM MY FUCKING ARM TO SLICE AND DICE LIKE THE RON POPEIL MAGIC SLICER. I MEAN, IF I HAD ONLY THOUGHT OF MAKING IT ON THE NETWORK FUCKING NEWS INSTEAD OF MY OWN SURVIVAL I GUESS I’D BE A REAL JOURNALIST. SERIOUSLY, LARSEN, I WAS SO SELFISH. LET ME GO BACK TO THE JAMES THOMPSON MOTOR INN AND SEE IF I CAN GET THOSE GUYS TO FINISH THE JOB, FER CHRISSAKES!”

On the other end of the line Larsen was chuckling in his well-bred Harvard way.

“Hahaha. Love working with you, Robert, but next time make sure you take the wound for the team, okay?”

“Holy shit! Fuck you, Jon,” I said and hung up.

I walked over to the mini-bar, got out two bottles of Scotch and downed them both in five minutes.

Then I fell into a deep, nightmarish sleep.

I woke up in the middle of the night, and thought, “Well, in a world of pretend outlaws, I finally met some real ones, and Delbert McClinton was dead-on. It wasn’t cool, not at all.”

On the other hand, I have to admit, having survived it, it makes for one hell of a good story. And that’s what being a journalist is all about.