New York is a city famous for its talkers, its riffers, rappers, and raconteurs. But let’s face it, a lot of them are seriously overrated—depend on canned routines and canned Attitude, self-congratulatory cynicism and stale camp snobbery. Ever since I came to Manhattan I kept hoping to partake of the promised feast of wit, but found, more often than not, name-droppers, know-it-ails, wise guys posing as wise men. You know who I mean.

Richard Price is one of the rare exceptions: he’s a talented novelist, a critical and cult favorite for The Wanderers and Ladies’ Man, a sought-after A-list screenwriter (The Color of Money, Sea of Love, the Scorsese episode of New York Stories) who’s written the scripts for two just-wrapped De Niro movies (Mad Dog and Glory and Night and the City). But as a talker he’s nothing less than a word-of-mouth living legend, one of the few in New York who actually deliver the goods.

“The guy is so fast it’s hard to keep up,” says his friend, novelist Pete Dexter, who won the National Book Award for Paris Trout and is no mean talker himself. “It’s like he’s already thought of everything you’re thinking of and he comes up with remarks in seconds it would take you an hour to come up with—if you ever did. What he does is make you feel stupid, the little fuck.”

It’s true: every time I’ve run into Price over the years, usually at a book party, he’s always surrounded by a circle of writers, editors, the type of people who are usually the smartest talkers in their circles, and Price is rapidly, effortlessly tossing off observations that cut deeper, ring truer than anything anyone else is saying that night or on hundreds of other nights of allegedly great New York talk. He’s kind of like Robin Williams, but with a real edge; he tells a story like Spalding Gray on amphetamines, and makes your average shock jock’s efforts to be down and dirty, hip and scabrous seem about as transgressional as Willard Scott.

“The cop who introduced me told me, ‘Don’t worry, you’ll be safe with Rodney. Nobody will fuck with you when you’re with Rodney—he’s a killer.’”

Still, there was one moment in the course of Price’s research for Clockers (Houghton Mifflin), his much-anticipated new novel about life in the crack culture of the urban projects, in which words finally failed him—one terrifying situation he thought he wasn’t going to be able to talk his way out of.

He’d set himself up for it, of course. He’d plunged into his research in the crack-plagued projects with the missionary fervor of someone who’d kicked a nasty coke habit himself some years ago. And who—seeing the destruction wrought by coke’s metastasis into crack—wanted to capture the dark heart of it in his novel. For payback and for penance, he wanted to find his way into the belly of the beast.

And so Price, forty-two, hung around with the cops who police the projects of Jersey City—the devastated urban center right across the Hudson from lower Manhattan—went on patrols with them, spent hundreds of hours with pregnant teenage users in family shelters, with tenants fighting crack and crime on their playgrounds.

But it still wasn’t enough. He knew he’d have to put in time with the perps. He’d gotten one of the cops who thought he ought to see the drug war from the Other Side to introduce him to a coke-dealer kingpin in the projects, like the one Price calls “Rodney” in Clockers. A guy who was not only a coke tycoon but a charismatic dark-side father figure to the dozens of beeper-equipped teenage salesmen (or “clockers”) he had out on the street, “mentoring” them by dispensing Ben Franklin-like work-ethic wisdom and career advice—a kind of coke-trade caricature of the old-fashioned capitalist entrepreneur. “A cross between Fagin and Bill Sikes,” as Price puts it.

“The cop who introduced me told me, ‘Don’t worry, you’ll be safe with Rodney. Nobody will fuck with you when you’re with Rodney—he’s a killer,’” Price recalls one evening in the lower-Broadway loft he shares with his wife and two daughters. “And I’m going, Great, I’m safe because he’s a killer.”

But the threat to his safety didn’t come from Rodney. The danger was that, when he was out there in the projects with Rodney, cops who didn’t know him would mistake him for a dealer. Or dealers who didn’t know him would mistake him for a cop. The novelist as the ultimate undercover agent, an operative for no one but himself, without even a journalist’s credentials to show a grand jury, or a kangaroo court in a crackhouse.

Which is what he thought he was heading for in one horrible four A.M. moment of truth. It was an incident that arose from what might be called an incomplete social introduction. It happened when Price was out cruising with Rodney, who was supervising his street-sales operation. The problem came up when Rodney offered to introduce Price to his biggest rival in the rock trade, a very large person on whom Price based “Champ” in Clockers.

“He’s a big kid, eighteen years old, Mr. Big. These cops I was running with would have retired if they could only have busted this kid. And Champ’s like—he’s got six baby Rottweilers he’s named after cops.”

The problem with meeting Champ, he told Rodney, was that Champ had probably seen Price out traveling with these very cops. “This squad of cops I’d been running with was there to torture, harass, strip, dickie-check, teeth-check all Champ’s boys. And Champ had seen me with the cops, when they’re like humiliating them. So when Rodney says, ‘You want to meet Champ?’ I say, ‘Well, I really would, but to tell the truth he’s seen me with that unit and he probably thinks I’m a cop, so I don’t think it’s gonna be so cool.’

“And Rodney says, ‘No, it’s cool, Rich, I’ll tell him, I’ll explain it.’ And you know, it’s like four in the morning and we pull up to these projects and it’s like the land that time forgot. There was this mist and these big high rises that looked like obelisks coming out of the mist. And there’s Champ, this guy who’s so big he’s in three separate Zip Codes. And he’s got all his boys with chains all around and cars are coming up and they’re selling dope and there’s no cops there. There won’t be a cop around for the next twenty-four hours. It’s complete impunity. There’s nobody there from my world, you know. And Rodney is going, ‘Oh, Rich, don’t worry about it, you’re with me, man.’”

As Rodney got out of the car to speak with Champ, Price says, he reminded him, “Now, Rodney, now wait a minute, don’t forget to tell him who I am, you gotta say ‘He’s a writer, you might have seen him with the cops but he was only with them doing a book, he’s not a cop himself.’ And he’s going, ‘Don’t worry, don’t worry.’ And I’m going, ‘Oh shit,’ I have this feeling he’s not going to tell him exactly what he needs to know.

“No no no, you don’t understand. No, I’m a writer, writer. I’m making a movie, I’m making a book, I’m making a movie and a book, and Billy Dee Williams is gonna play Rodney.”

“And Rodney gets with the kid, Champ, and he puts his arm around him and they’re walking off together and in a minute these two guys, it’s like this prison shit: they’re insulting each other and fake fistfighting and it’s ‘Yo! Why are you calling me a pimp, you fat motherfucker?’ and they’re hitting each other and they’re like trying to fuck each other in the ass. I mean, this was all like saying hello, you know.”

Price was having major misgivings about whether his introduction would be phrased right.

“It’s not like Rodney is going to interrupt all this shit to say what I want him to say, you know, ‘He’s a writer, you saw him with the cops but he’s not a cop.’ And I’m sitting in the car all by myself and people are looking at me, but they’re not going near me because I’m in Rodney’s car. It’s like ‘Don’t hit him until Rodney says it’s O.K.’

“And about five minutes later this guy Champ comes loping out of the mist, a huge guy in a white shirt and big white baggy shorts coming through the mist like a two-legged dinosaur coming at you, and he’s coming over to the car and he looks at me and his eyes kind of go, ‘Oh shit, Rodney, you brought a motherfucking cop!’ I figured Rodney told him, ‘I’m with a writer and he’s O.K.,’ and forgot to explain about him seeing me with the cops. And this guy obviously thought I was pulling a fast one. And he’s shouting, ‘The motherfucker’s a cop!’

“And all the kids come running and their chains are jangling and they’re loping toward me like they’re doing an L.L. Cool J thing. And they’re running towards me, I’m going, ‘Oh my fucking ass,’ and I don’t see Rodney anymore. It’s ‘God, I can’t believe this. Why am I doing this?’ And then I have to get out of the car. I say, ‘No no no, you don’t understand. No, I’m a writer, writer. I’m making a movie, I’m making a book, I’m making a movie and a book, and Billy Dee Williams is gonna play Rodney and I wanted to meet you, because I’m not a cop, I don’ t even like those guys.’ And finally I got through. But some of these kids wanted to beat the shit out of me anyhow. So I didn’t stop talking and I had my novels in the car and I was holding up my novels, you know, it’s like ‘Look! Look! I’m a writer! I brought my novels!’”

It was a dicey situation but one that soon turned into a moment of truth as stark and brutal as a medieval morality play, so melodramatic Price kept it out of Clockers for fear of seeming to stretch the fabric of realism:

“‘You’re making a movie about this thing?’ Champ says to me. ‘You want to know what it’s about? You want to know what’s happening around here?’ He goes like this, snaps his fingers, and one of his boneheads comes over and gives him a clip, which is like ten little bottles of coke bound in a cylinder with a rubber band. ‘It’s about this,’ he says. ‘You want to see something?’ He takes out one of these little bottles, you know, it was like a tenth of a gram. And some of these noddies are walking around in the mist, they’re looking in the grass for like, you know, a bottle someone threw away with like a trace of residue in it.

“And Champ says to one of them, ‘Yo—get over here!’ And it’s like ‘Yo. What’s up, Champ? What’s up? What you want?’ And he says, ‘Stand over here, just stand here for a minute.’ And he can see the bottle—it’s like pay dirt. And Champ is looking around and he pulls over another guy and he says, ‘Yo! Get over here.’ And it’s ‘Yes,what’s up, Champ? What’s up?’ He says, ‘You go over there’—so they’re facing each other. And Champ says, ‘You two know each other?’ And one guy says, ‘Yes, we know each other, we grew up together.’

“And Champ says, ‘I want you two guys to fight each other for this bottle.’ And one of the guys starts saying, ‘You know I ain’t gonna hit my man.’ BOOM! The other guy knocks him down, takes the bottle, and vanishes.

“And Champ says, ‘That’s what this is about. I got me an army out there. These motherfuckers do anything for me.’”

That’s what this is about. Price is fond of recalling a story about Stephen Crane, about the way the author of The Red Badge of Courage behaved when he was serving as a correspondent in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. “Crane would make a point when the bullets were flying of standing up and lighting his cigarette. And not getting down until he got it going properly.”

Price doesn’t regard Crane’s showboating behavior as courage. He thinks “the guy had a problem—let’s face it, he was overcompensating.”

While some are likely to say it’s impossible, if not “forbidden,” for a white writer to truly express the humanity of black people, others will undoubtedly say Price has transgressed by making his coke dealers and users too human.

Price should know: he’s got the same problem, he says. And he does seem to share a penchant for making himself a target for the sake of his art. Which Clockers will undoubtedly do. It has all the makings of a big book (Universal paid a budget-busting $1.9 million for the film rights and the screenplay—Scorsese to direct—while the novel was still in manuscript). And perhaps a big controversy.

There are those who will say that this is hubris, that no amount of overcompensation will suffice for a white novelist to succeed in writing—as Price does for a good half of Clockers—from inside the heads of the black denizens of ghetto housing projects.

Presumed Innocent author Scott Turow alludes to this obliquely in a generous pre-publication quote about Clockers: Turow calls it “remarkable, The Bonfire of the Vanities as rewritten by Nelson Algren,” and adds that “it is a book of considerable bravery which refuses to declare the imagination out of bounds when it wanders onto terrain that others might wish to call forbidden.”

While some are likely to say it’s impossible, if not “forbidden,” for a white writer to truly express the humanity of black people, others will undoubtedly say Price has transgressed by making his coke dealers and users too human, by humanizing rather than demonizing the perpetrators of crack-addict culture. Still others may object that he’s humanized rather than demonized the casual racism of his white cops.

Of course, he’s aware of all these objections, he’s raised them himself. Nobody knows better than Price that writing a novel like Clockers is the equivalent of standing up in a cross fire and slowly and deliberately lighting up.

Which, you sense. is part of the appeal for Price. One of the cops he’d spent time with remarked that when they went on raids into hostile crack-house territory. ‘”we kept telling him to stay in the car, but that skinny motherfucker would be running through the door with us”—the only one without a gun or a bulletproof vest.

“I mean, when I heard him say that,” Price tells me. “I said, ‘Wow, I did that? I think of myself as a physical coward. It’s all overcompensation. I mean, my family crest was like crossed thermometers on a field of aspirin,” he says of the nervous, overprotective lower-middle-class Jewish family he was nurtured in, growing up in the Bronx projects. In addition, he had something more to compensate for than most kids: a childbirth accident left him with a right arm partially crippled from cerebral palsy. “The doctor was shooting speed and bungled the delivery,” he says with what still sounds like some serious anger. It affects him to the extent he has to shake with his left hand. He reports that the Jersey cops he ran with called him “that Dustin Hoffman-looking motherfucker with the bad arm.” (In fact, it’s not Dustin Hoffman he reminds you of; the vibe, if not the literal resemblance, is more wired, more James Woods.)

Where he came from was the Parkside Projects in the northeast Bronx, a city-built postwar housing project for blue-collar families both white and black.

It was overcompensation that compelled him to go where few straight men had dared venture before—into the wildest, baddest, most extreme underground gay sex bars in New York during the pre-AIDS frenzy of the late seventies, to accumulate experience for Ladies’ Man, a brilliant novel about New York loneliness that had highbrow gay academic critic Martin Duberman calling it “the best gay book of the year” in 1978, despite its straight author.

The achievement was particularly impressive for Price, growing up as he did in a white working-class culture which was both homophobic and hostile to creative aspiration. Or as Price puts it, “Coming from where I did, it was like if you’d write a poem you’d probably suck a dick.”

Where he came from was the Parkside Projects in the northeast Bronx, a city-built postwar housing project for blue-collar families both white and black. Price’s father briefly owned a hosiery store, was a window dresser at Modell’s discount department store, and drove a cab. “I was the first kid in my family to go to college and my parents were haunted by the Depression and it was like ‘We work all our lives to send you to college and what do you want to do with your education, you want to be a writer? What are you, making fun of us?’ ”

So intimidated was he by the pressure to enter a profession that when he was accepted at Cornell he matriculated at the School of Industrial and Labor Relations rather than the liberal-arts college.” I thought it was like public relations—l’d be doing campaigns for clean ears. I thought it was my duty to get a job, not like go to school four years, then drive a cab so I could go to creative-writing classes.”

Which was what he ended up doing anyway—at least until Saint Jude intervened.

His ambition was born on the bus up to Cornell, his freshman year, when he first read Lenny Bruce and, soon thereafter, Hubert Selby’s Last Exit to Brooklyn. “That was the most important book of my young life,” he says. “It was the first time I felt like my own experience was valid grounds for literature. I mean, my people are more conservative, less desperate, but I recognized Selby’s people, I felt like I knew these people.”

Price started taking writing courses at Cornell, which had produced such maverick talents as Richard Farina and Thomas Pynchon. But what turned his impulse into a compulsion was the response he got to his first reading. “It was some sort of free-form poetry about growing up in the Bronx, but people really reacted to it. And I got this buzzing in my head like more, more, more. It was like sex.”

So badly did he come to want it that when he couldn’t afford the tuition at a graduate writing program “I actually wrote prayers to Saint Jude for intercession,” he says.

“Saint Jude?”

“Yeah, what happened was I got into Wallace Stegner’s graduate creative-writing program at Stanford, but I didn’t have any money, and there was a waiting list of three people ahead of me for scholarships. I was living with my parents and ready to kill somebody when I saw this ad for Saint Jude, the patron saint of hopeless causes. I wrote a letter to the shrine, basically a solicitation for money. And this priest wrote me back and said he was going to the Vatican and he’d take my letter and remember me in his novenas. And I swear this is true—two days later I get a call from Stanford saying four of the people who got a scholarship had turned it down, and I got it. It had never happened before.”

One is tempted to say that Saint Jude must have also had a hand in the success of Price’s first novel. It came out in 1974, and it achieved for him in the seventies something akin to the instant success Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis enjoyed in the eighties. He was a one-man Bronx-boy Brat Pack.

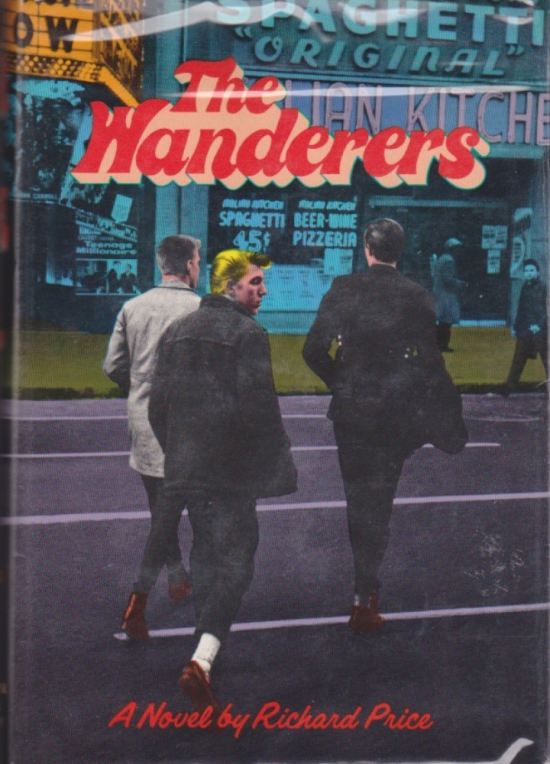

The Wanderers has the same rough-edged romanticism, the same yearning side of the bad-boy-in-the-black-leather-jacket that Springsteen songs celebrate.

The book that became The Wanderers was a series of short, loosely linked, magic-realist accounts of Bronx street life told in the voices of gang members. Price had originally submitted it to Houghton Mifflin, the prestigious Boston publisher, as a book of short stories under the title The Wanderers: Tales of Greaser Passion. But a smart editor there had the smart idea to lose that subtitle, get Price to connect the stories in a year-in-the-life format, and publish the book as a novel.

It appeared to admiring reviews (one from Hubert Selby in the Times Book Review, who called it “a superbly written book… that forces us to feel closer to other human beings whether we… approve of them or not”) at a time when a sixties-weary culture seemed ready for gritty and lurid fantasies of the greaser era. It soon became a cult favorite if not a best-seller; its appeal went beyond blue-collar readers to a generation of suburban baby-boomers encountering the disturbing complexity of adulthood and looking for a romantic Myth of Origins in the retrospective “He’s a Rebel” sound track of their youth.

Price tells a funny story about being at a noisy party in the late seventies and being introduced by the great Dion to a musician whose name Price misheard in the din as “Maurice.” “So this guy Maurice is telling me how much The Wanderers influenced his music and I’m going, ‘Yeah, great. Maurice.’ And then he told me his name wasn’t Maurice, it was Bruce—Bruce Springsteen.”

Which is appropriate because The Wanderers—and Bloodbrothers, Price’s second novel, also set in tough-guy Bronx-projects culture—has the same rough-edged romanticism, the same yearning side of the bad-boy-in-the-black-leather-jacket that Springsteen songs celebrate. The Wanderers became a terrific film of the same name directed by Philip Kaufman, and a favorite of street-guy movie types like Martin Scorsese and Don Simpson. The hyperkinetic producer once told me, “The Wanderers is, I swear to God, maybe next to Moby Dick, my favorite book of all time. When I finished The Wanderers I felt like part of my life was over. I mean, I was sad. I was like depressed. It pissed me off that he didn’t write nine Wanderers.”

Which was part of the problem for Price. He didn’t want to repeat himself. Felt he’d already mined his boyhood in the Bronx projects to the point of creative exhaustion. “I didn’t want to be the Dion of literature,” he says, living off the golden oldies of his youth. By the early eighties his novels had earned him a lot of respect but not much money, and he was hearing the siren call of producers who were offering him hundreds of thousands of dollars a shot to write screenplays. “There’s no sin in wanting to write screenplays,” he says now. “The sin is being good at them.”

His screenplay career at first seemed to defy the usual New York writer/Hollywood sellout/cynical disillusion/Fitzgerald crack-up cycle. He turned out scripts that were edgy and powerful (particularly in their first drafts). And contrary to the typical writer-gone-Hollywood story, he didn’t pay the customary price in loss of respect, loss of literary credibility. In part because he stayed in New York (preferring marathon phone conversations with producers to flying to L.A.), in part because he kept all his New York friends entertained with wickedly funny accounts of Hollywood pitch meetings.

“You know, the nightmare of coke is that you’re always aware that at some point you’re gonna run out. No matter how much you have. Therefore, the clock is your enemy.”

Still, if he didn’t lose his downtown credibility. Price did begin to feel he’d lost his way. Part of it was the coke. After Bloodbrothers and Ladies’ Man (which took him out of the Bronx and into the lonely heart of contemporary Manhattan), he got bogged down mining his Bronx past for a novel that would become The Breaks. And by that time coke was digging him deeper:

“After Ladies’ Man, in 1978, I ran out of ideas. I was getting bored with my own autobiography and I had written two false novels that went nowhere and I didn’t even send out. I was in a panic and I just started doing coke. And, uh, then the coke took over. There’s nothing I could say that’s not a cliché you haven’t heard a million times before. First you’re doing coke so you could write. Then you’re writing so you have an excuse to do the coke. It was just a very bad two-to-three-year period in which I sort of banged out the rest of The Breaks.”

The coke, he says, is what got him into doing screenplays, which turned out to be a much harder habit to quit. “I figured since I had a coke habit anyway I might as well get into screenwriting.”

But as it turned out the coke crippled the screenwriting too. “Every day I’d write a great page, but it had nothing to do with the pages I wrote the day before, so I’d have a hundred great pages for a hundred different stories and I just couldn’t get it together. It got to the point where I’d have to do a line to write a line, and it became a terrible strain on my health, my life—everything.”

“I mean, People magazine is filled with these like wildly successful assholes that used to have drug problems…and they’re still fucking assholes.”

Now, he says, when he gives talks at junior high schools as part of a drug-awareness program, he talks about the way coke turned him into a clocker: “You know, the nightmare of coke is that you’re always aware that at some point you’re gonna run out. No matter how much you have. Therefore, the clock is your enemy. You sit at a dinner party and it’s like ‘How often can I go to the bathroom for a refill without people getting suspicious?’ It’s the tyranny of the clock—time is always running out on you.

“And at one of those schools the kids are like taking pity on me, they’re saying, ‘Well, why didn’t you tell your girlfriend?’ I said, ‘Because then she would make me stop.’”

Finally, he says. he knew he had to stop. It was 1984, he was living with his soon-to-be wife, Judy Hudson, an attractive downtown artist. “We were planning a trip to Italy and I decided, That’s it, I’m going to stop. l was terrified. Because it’s always there and you always know how to get it. And what you’re afraid of is yourself. You’re afraid of your own weakness. But when I got back I found something miraculous happening: I started writing because I could concentrate.”

Price disdains the self-congratulatory piety of post-rehab New Sobriety celebrities. “I mean, People magazine is filled with these like wildly successful assholes that used to have drug problems, and there they are on the beach at Santa Monica with their one-year-old, Ashley, and their other kid, Aaron. and it’s like ‘Well, you wouldn’t believe the way I used to be.’ And meanwhile you know they’re still a bunch of fucking assholes.”

Still, it was his recovery process that gave him the impetus to do Clockers. “The thing about the drugs is it did play a big part in my wanting to write this book. I mean, I never did anything but sniffing. I didn’t have like that eight-gram-a-day habit—just enough to ruin my life, become a major preoccupation, and affect every element of my life in a negative way.” But about the time crack started coming in, Price was going to the Daytop Village rehab community. Not for his own habit, but as a kind of penance: he was teaching creative writing to some of the recovering teenagers there.

“Basically, you’re talking about teenagers—nonwhite, broken homes, completely disenfranchised—and they’re doing this drug that’s ten times worse than regular, watered-down cocaine. And I’d say to them, ‘Listen, I was like thirty-two, had published novels, had money, and I almost went completely down the toilet. Here you are, you’re not out on your own yet, you’re in a society dominated by white people, you got problems at home’-—it just blew my fucking mind that these people were in such worse shape on paper than me and they were dealing with a drug so much more potent, thinking that it would help them cope. And it just… the thought of crack got under my skin and just like seized me… I felt like I had to run to it. I felt there’s something about this crack thing… I’m from the Bronx and I was born in the hospital right behind Daytop Village and I had to run headlong into the bowels of this crack thing. I just wanted to reach out and like take the essence of what it was about. Plus, it was also going back to my roots as a writer. I started out with The Wanderers, writing about housing projects. I was writing about housing projects again.”

Which is what brought him to Rodney, the rock-coke king of the Jersey City projects. And finally it was Rodney who brought Price—a man whose struggle to kick his habit had left him “afraid of his own weakness”—face-to-face with the snows of yesteryear for the first time since he’d quit.

It happened at Rodney’s place, an apartment in the projects, one night after Price had earned Rodney’s provisional trust out on the streets. This was the first time Rodney had shown him the product. It was, the way Price describes it, a chunk the size of a small meteorite. “I’d stopped doing coke and I hadn’t even seen it for years and years. He sets it down on this tacky table between us and he pulls out his big bowie knife and starts stabbing it, chopping it into golf-ball-size lumps. I’d never seen coke this color before. It was kind of light brown, it was so pure it wasn’t even white—white means a lot of cutting agents. And I’m looking at it, but… It’s like not my world. This is not my coke. This is not—you know, it’s not like doing it at the Odeon, let me tell you.”

Would he be tempted? Would he abandon his hard-won sobriety?

“I was leaning over the table watching him carve out rocks and I just felt like… no desire whatsoever. Because the last thing I want to do is a little hit. I mean, the only thing worse than no coke,” he says wryly, “is just one line. Fifteen minutes later and I’d be strung out of my mind in Rodney’s world.”

He survived that test, but suddenly another kind of threat manifested itself. Price’s reverie on the rock of coke was interrupted by a noise at the front door, and a panicky Rodney began acting as if a SWAT team was about to blast its way in.

Price recalls how Rodney’s demeanor changed. “Here’s the big bad coke-dealing motherfucker and he’s telling me as he stabs the block of coke how he deals with guys who cross him. ‘First time, you fuck them up; second time, you kill them, man…’ But as soon as he hears the sound at the door he’s taking the dope and hiding it and going, ‘Oh shit.’ ”

Price too was running scared, at least in his head. “I had this image of a police raid with a camera crew from Cops coming through the door and I’m caught in a freeze-frame on national TV trying to explain that ‘no, see, I’m really here as a writer.’ And the next thing you know I’m giving interviews to the Bergen Record from jaiI.”

In fact, as it turned out, Rodney knew it wasn’t Cops coming through the door, knew from the sound of the key in the lock it was someone he feared far more: his wife. You see, says Price, “Rodney’s been married twenty years to a deeply religious church-lady type.” And Rodney swears she doesn’t know what business he’s in. “So it’s like he gets the dope hidden away and she comes in and it’s ‘How you doing?’ and I’m saying, ‘How are you, ma’am?’ And she says, ‘With the Lord.’ With the Lord! They’re married twenty years and she doesn’t know? She’s gotta know. Or maybe…”

Price goes into an extended riff on the perverse strength of this marriage, the unspoken understanding, the underpinnings of evasions and elisions, the enormous delicacy of the arrangement: she pretends not to know, and he pretends not to know she knows, and they both pretend not to know they’re both pretending.

It is this novelist’s eye for the plangent complexity and unpredictability of human relationships that distinguishes Price’s fiction. I was concerned when I first approached the huge manuscript of Clockers that, with its sensational subject matter—murder, coke, crime, cops—and with his years of writing page-a-minute dialogue for screenplays, what would be lost would be the kind of constantly surprising intimate observation of behavior that made his previous novels so illuminating. But, in fact, what makes Clockers so impressive is that on nearly every page there’s a moment of acute perception of the kind that distinguishes novelistic realism of a high order from the clichéd realism of “reality” shows like Cops or the neo-Superfly clichés of New Jack City—moments that are object lessons in the difference between the emblematic and the generic in fiction.

One moment I’m particularly fond of takes place in a bar; two key characters, Strike and his older brother, Victor, are having drinks together. Strike is Rodney’s upwardly mobile protégé, the one who’s so conflicted about his rise in the corporate hierarchy of coke dealing that he’s given himself an ulcer. Unlike Strike, Victor has been trying to bootstrap his way out of the projects playing by the rules, supporting a wife and family with an exhausting schedule that has him working as a security guard in a Columbus Avenue boutique by day, then hustling back to New Jersey to serve as the manager of a fast-food franchise by night.

Victor’s bitter because he’s working himself to death and it still isn’t enough to keep his weary head above water, while his younger brother, who’s willing to break the rules, is raking in thousands of dollars a week and supervises his own crew of “clockers”—he’s an executive.

“It’s not like the difference between black and white behavior is so exotically different that your own experience is null and void simply because you’re not black. I mean, you know, the human heart’s the human heart. I mean, people yearn.”

That night at the bar, something’s brewing inside Victor, something bitter and inconsolable, but Strike doesn’t see it, just feels pity for what a sucker his working-stiff brother is. Pity that turns to contempt when he sees his brother doing this peculiar thing he does, writing the names of imaginary teams on his cocktail napkin, teams with names like “Washington Warriors” and “Dallas Devastators”:

Strike shook his head. Goddam he’s still fucking around with that dumb-ass “aroundball.” Two years earlier, when they’d shared a bedroom, Victor jumped out of bed one night and started to write down the rules of a game he’d just dreamed about. He called it aroundball, but Strike never understood how it was played—it seemed to him like a cross between dodgeball and soccer. The game had become an obsession of Victor’s; for months he was writing up new bylaws, or trying out new names for the franchises.

What’s really going on here, what Victor’s really dreaming about, is not a new sport but a new world played by his rules, a dreamworld that rewards him for his hard work rather than breaking his heart and bestowing its favors on those like his brother who make their own rules. It’s a beautiful way of expressing what’s going on inside an honest man trapped in a dishonest world.

And a bit later on there’s another telling moment when Victor, in an internal monologue, is cursing himself for something he said earlier that day at the boutique where he works. It seems an attractive, well-heeled woman, trying on a kimono, asked him how it looked on her. And Victor, trying awkwardly to make an impression, told her, “You look davishing,” knowing almost instantly he’d gotten the word—and maybe the world—he aspired to mortifyingly wrong.

It’s moments like these that make Clockers transcend its sensational cops-and-coke-dealers setting. Price, who’s reluctant to be caught out describing, much less praising, his own fiction, does concede he has “an eye for the poetry of misnomers, the poetry of non sequiturs. I mean, compared to Robert Stone talking about God and man, I feel like a dung beetle: I’m just trying to get the convolutions of the hair and the shit right. But I can nail the way people really talk, I can nail a gesture dead on. I’ve got like X-ray eyes for the little gestures that go right by everybody. I don’t go for the big picture so much as a lot of little big pictures.”

Jersey City. “The Iron Triangle of Hell.” That’s what Price calls this zone of devastation, this wasteland within a wasteland we’re driving through now. It’s a vast field of scrap and garbage and what looks like rusting toxic-waste canisters in the ravaged heart of this crumbling urban center. Jersey City has all of the plagues and ugliness but none of the glamour or attention of big cities like New York and L.A. No mythic Crips-and-Bloods gang-war grandeur; no Renaissance past like Harlem’s; no visibility in the media. Just a cruel, vicious, remorseless process of degradation.

Price is describing the intricate ecology of the Iron Triangle of Hell, the way junkies with shopping carts scrounge through the garbage for iron and other scrap metal to sell for pennies a pound to buy drugs from the dealers at one vertex of the triangle, then head for the methadone clinic across the way, where they get paid to take an AIDS test (and never ask for the results). And then there’s the final vertex, “this Gothic ziggurat,” Price calls it, a vast, soot-blackened, pre-war hospital complex. “That’s where they all go to—to die.”

The emblematic moment of his long journey through this Hell, Price says, was “when I walked into this shooting gallery and it was like knee-high in hypodermics and everything. And in the middle there was a headless dove.”

“A headless dove?”

“I mean, who was so unsubtle as to rip the head off a dove?”

Still, the question will be raised: Despite the three years he spent haunting the Iron Triangle of Hell, can a well-off white writer ever be more than a tourist?

“He’ll probably catch some shit about it,” Pete Dexter says. “You know, how does a middle-class white guy pretend to know what it’s like.” Dexter thinks Price’s success in getting “inside that kid”—Strike, his upwardly mobile clocker—refutes the objection: “It’s really bullshit because, when you come down to it, what emotion is in this kid’s head that I don’t know anything about?”

Nonetheless, one night at Price’s loft I was witness to Price’s “catching some shit” on this issue from a visitor: “Don’t you think there’s something patronizing about you coming from New York and sort of studying the natives and then—”

“I’m not studying the natives,” Price interrupted heatedly. “There’s nothing patronizing. I mean, I’m not a painter, but I have a perfect right to do a painter in ‘Life Lessons’ [the Scorsese-directed segment of New York Stories, starring Nick Nolte as a troubled artist.] I’m not saying what I did is the truth, but it’s honest—this is what I saw, what I know. I mean, I felt inspired by what I saw, I felt like writing like I never felt like writing before. And, you know, Jersey City is right across the river and people just don’t know what it’s like to live there, what it’s like to be a kid in the Curries Woods project. Because the people that live there and know about it don’t become writers. I mean, let some guy from Martin Luther King Drive in Jersey City write the story. I’m not in competition with anybody. But I’m gonna get in there. I’m gonna get the news. I’m gonna bring it back and I’m gonna convert it into art.

“What I had to learn about this book is—I started thinking about Strike and this kid Tyrone, this eleven-year-old who idolizes Strike and who is on the verge of giving his life over to the dealing hierarchy, and I kept thinking, What would a black kid do here, what would a black kid do there? Is this cultural imperialism? And then, after actually hanging out with these kids, I realized, Why am I saying ‘black’ all the time? What would an eleven-year-old kid do? That’s the baseline. It’s not like the difference between black and white behavior is so exotically different that your own experience is null and void simply because you’re not black. I mean, you know, the human heart’s the human heart. I mean, people yearn. They yearn for the same things, maybe with a different brand name, but it’s the same yearning.”

The challenge in writing Clockers, he says, was to repress the hipster in favor of the detachment of his scientist side—to submerge the pyrotechnic narrative voice that had been his stylistic signature in his previous novels.

As for another potential source of controversy about Clockers—the casual racism of the cops—Price says, “Cops are empiricists: because of their job they see people at their worst” and make the worst extrapolations about them as a group. The way Price describes it, what comes across as casual racism derives from a deeper, even darker source—a kind of universal bottomless cop cynicism about all human behavior which often expresses itself in a perversely upbeat gallows humor.

He cites a horrifying example: a phrase the cops he ran with used—an appallingly cruel, hideously cynical cop worldview compressed into a single three-word phrase. Price was telling me about the cop notion that there’s a peculiar self-limiting factor built into the dynamics of America’s Iron Triangles of Hell. That crack, needle drugs, AIDS, and crime are killing off so many victims in the ghettos, both predators and prey, that the multiple plagues are beginning to burn themselves out, for lack of new souls and bodies to consume.

“You know what the cops call that?” Price asks. “The self-cleaning oven.”

The impetus for Clockers, however, the mainspring of its plot, is the determination of one white homicide cop to overcome his cynicism and racism and find a reason to care about the fate of one young black murder suspect no one else wanted to think twice about. The plot device grew out of a memorable moment in the course of a real murder investigation Price was tracking with a homicide detective.

“He’d got a confession from a kid, but even though he had the lockup, in the back of his head it’s like ‘What if the kid didn’t do it? Maybe he’s taking the pressure off somebody else, withholding the real reason. If the true circumstances come out in court, I’m gonna look like a horse’s ass. I got to know why this kid really did it.’

“So we go to the parents’ house, they’re watching Dynasty. They can barely turn away from Krystle and Blake, you know, they’re not helping him. And the detective finally figures, ‘Ah, to hell with it’—you know, ‘The kid’s locked up; it’s not my problem.’ And as he’s walking out of the house there’s this shelf of tchotchkes, and he says, ‘Uh, can I borrow this picture?’—he wants to use it to question the kid’s friends. And the parents say, ‘What do you want that picture for? That ain’t him.’ And he says, ‘No? Gee, it looks just like him.’ ‘Yes,’ they say, ‘that’s his twin brother.’ ”

Suddenly, a whole new dimension to the case opened up: was one twin sacrificing himself for the other? “You know,” Price says, “God’s a second-rate novelist.”

The decision of the cop in the novel to care more than the job calls for is a stirring moment: it represents one of the few times when a human impulse transcends what Price refers to as “the algebra of need” (a William Burroughs phrase) and “the arithmetic of mortality” (Price’s term) that otherwise rule human interaction so rigidly in the projects.

Algebra? Arithmetic? It was Robert De Niro, as far as I know, who first used the word “scientist” in connection with Price. I’d put in a call to see if the taciturn actor would have anything to say about the unusual fact thai he was playing two Richard Price characters in a row. And to see what he’d have to say about Price himself, as a kind of semi-legendary New York character. About the latter, De Niro was not very forthcoming. “Richard,” he said, laughing. “He’s a very sick man.”

But he had a lot to say in praise of Price’s ear, his dialogue, the way it often sounds “crazy, off-the-wall, or preposterous, yet when you meet the actual people he wrote about, it’s very true.”

I asked him about the two Price characters he’s just played—Wayne, the painstaking crime-scene cop in Mad Dog, and Harry, the fast-talking hustler lawyer in Night and the City. Did they have anything in common? “I mean,” I said, “they’re both desperate dreamers—”

“No, I don’t buy that,” De Niro interrupted. “I don’t think they have much in common. Harry’s very flashy, he’s from the hip, and Wayne’s very methodical, he’s like a scientist.”

De Niro is talking about two different Price characters, but he could have been talking about two sides of Price himself. Because while he’s a fast-talking, droll, and sardonic hipster type in person, in his prose he can be a methodical precisionist, a craftsman, a scientific observer of human behavior. The kind of scientist who looks for continuities rather than discontinuities, continuity between black and white behavior, continuity between the projects of his youth and the projects reigned over by Rodney and Champ.

The challenge in writing Clockers, he says, was to repress the hipster in favor of the detachment of his scientist side—to submerge the pyrotechnic narrative voice that had been his stylistic signature in his previous novels. “My editor [at Houghton Mifflin], John Sterling, said, ‘This is a big book and it’s about some serious subjects. First thing we gotta do is get rid of all that pyrotechnic shit because otherwise your narrator is gonna be in competition with the characters and it’s just gonna be one voice too many and the whole place is gonna explode. What I want you to do is—the best thing that you do, your ace in the hole, your voice—I want you to obliterate it. I want you to write as neutral as you can. Let your characters run the show.’ ”

Excising the subjective point of view is a difficult task for any novelist, but Price had displayed an impressive talent for this sort of detached objectivity in the investigation into gay orgy clubs that inspired him to write Ladies’ Man.

The origin of the novel, he says, was a deal he made with Penthouse magazine to investigate sex bars in New York. “I started out with straight singles bars. And then the next night I went with an old friend of mine from college who’s gay. And he took me to these places like the Stud, the Anvil, the Speculum—you know, sort of dress-up-and-get-banged-in-the-ass gay bars. And I’d never been around anything like that. And first, you know, I’m scared. My heart is going whomp-whomp. People are getting blown, fucked, and sucked all around me. And I never saw that. I never saw another man’s hard-on in my whole life. And my friend disappeared and I’m all alone with my fucking notebook.

“And all of a sudden, after about fifteen minutes, I start realizing that I’m a little miffed since nobody’s making a pass at me. It’s not that I like wanted a boyfriend, but it’s the same dynamic as the straight singles bar. You know, that algebra of need. And I’d been thinking about what to write after Bloodbrothers. And I just said, Man, seven days in the life of a guy whose mooring gets snapped. His girlfriend dumps him, he cuts loose, feels complete anarchy, and an old college friend who’s gay takes him into that world.

“For all this rampant acting out—I mean, I went to places that I saw people handcuffed in bathtubs with funnels in their mouths—I have a feeling that this pre-AIDS gay life was a realization of some kind of male sexuality, not just gay. That straight men wanted to act out but were never able to do. It has nothing to do with homosexuality or heterosexuality; it’s just men have this sexual aggressiveness. And when you’ve got a whole sexual arena that’s men and men—you know: stand back. I mean, I never heard of any lesbian places like the Anvil.”

“This is my little kingdom tonight,” Price is saying. “These four square blocks.”

He’s standing on the sidewalk in front of his building, on the hectic stretch of lower Broadway between Tower Records and Shakespeare & Company, and there’s some truth to his tongue-in-cheek “kingdom” claim. Just around the corner in an alley off Bond Street the crew for Night and the City is filming De Niro’s final scene. Price stops in one trailer to schmooze with director Irwin Winkler (Guilty by Suspicion). Then a few steps down he ducks into De Niro’s trailer to say hello to the star, who’s looking dapper in a slightly garish way in an electric-blue blue sport shirt. (“His whole wardrobe’s from Moe Ginsburg,” Price says, referring to the splashy lower-Manhattan discount clothing store. “I specified it in the script.”)

Then it’s two blocks north and one block west to Mercer Street, site of the Bottom Line, where he’s doing a reading from Clockers on a double bill with Jim Carroll, the legendary ex-junkie neo-Beat poet. When Price arrives, there’s a full house of very downtown types, including a remarkable number of gorgeous Pre-Raphaelite, neo-Beat-type babes in black.

I have a sense that, although he’d never let on, this occasion is particularly satisfying for Price—not because of the women, but because it confirms that he hasn’t lost his longtime status as hip downtown writer-icon. despite having gone Hollywood in a financially humongous way. He’s here to read from a book which hasn’t been published yet but which has already netted him $2 million from Hollywood. But he’s still paired with Jim Carroll, who reads poems about watching Allen Ginsberg jerk off—very hardcore, no-compromise stuff—on a downtown bill. What more could any New York writer want?

“I used to be a novelist, before I was a screenwriter. Now I’m a novelist again.You know, with a big N.”

That night, however, there was a momentary echo of the time when Price thought he’ d lost it—his soul, his credibility—in those hours of script discussions with the Hollywood types who loved him too much. You could hear it in his description of what he was really aiming for when he wrote The Color of Money for Scorsese and Paul Newman. Earlier in the evening I’d asked him what that convoluted tale of macho consciousness was really about.

“It was really about me making four hundred grand,” he said, laughing. Then went on more seriously: “It’s about a guy [Newman as Fast Eddie Felson, retired pool hustler extraordinaire] who creates a Frankenstein monster. He takes a kid who’s pure [Tom Cruise], and he, you know, he dips him in the acid of his own experience. But in the process of creating a Frankenstein monster [turning Cruise into a hustler like himself], he discovers the purity of himself before he became this thing, and now he wants to be a pure player, but he’s unleashed this monster and it’s roaming the country.

“And it’s about getting hold of this kid and making amends. He’s destroyed this kid, he’s created this monster of cynicism—and it’s about paying the price. You know, paying the price to achieve a state of peace and a state of grace.”

It to me as Price was going through this impassioned and painstaking explication of the film—or at least of the first draft, before he had to make it “less dark” for Newman (“Paul likes to play rogues, but he won’t play villains”)—that what he was really describing was the price he paid, the struggle that had been going on within himself. Between the “pure player”—the novelist—and the “Frankenstein,” the “monster of cynicism” he became when he turned into a monstrously successful Hollywood screenwriter. And how in doing Clockers, in returning to novels, “he discovers the purity of himself before he became this thing.”

I asked him if there was any truth to this parallel.

“Well, I told you, I don’t like to think in meta-terms,” he said irritably. Then he grudgingly conceded: “Well, I didn’t think so when I was writing the fucking thing, but you know, in retrospect I could say, yeah, maybe.”

A more forthcoming and definitive answer comes later that night when he takes the stage at the Bottom Line and begins to introduce the section from Clockers he’s going to read.

“Um, the last time I was here, I was reading from screenplays,” he tells the audience. “And this time I actually have a book. I used to be a novelist, before I was a screenwriter. Now I’m a novelist again. You know, with a big N.”

[Featured Image: Sam Woolley/GMG]