Richard Pryor may be the funniest, if not the most obscene, comedian in the world. On stage, he exploits all the social norms and taboos. The most intimate moments of human behavior are laid bare as he speaks candidly about what most people think, but are too ashamed to express verbally. Pryor’s characterizations, which range from portrayals of high political officials to a flipped-out acid head, are unparalleled. Whether he satirizes current news events or acts out a conversation between a wino and a vampire, Pryor’s methodology sets him apart from his contemporaries. Most comedians who speak in the vernacular are considered vulgar. Pryor is no exception but he sets a new precedent in relating his material to his audience by explicitly using the vernacular and physical style that only exist in the mean streets of the Black ghetto. It is through this street idiom that Pryor becomes social commentary, giving a performance that is hilariously funny for some and painfully embarrassing for others. His ruthless attack on Whites in the audience and the White lifestyle is almost like a personal vengeance, while simultaneously many Blacks squirm in their seats with obvious discomfort. “Y’all can become Muslims now and join the Nation of Islam,” blurts Pryor to the Whites in his audience. “Ain’t nothin’ you people can’t have. And you wonder why Black men hold on to their crotches. We have to check, ’cause y’all done took everything else!”

Unlike most of his contemporaries, Pryor does not merely talk about or belittle his characters, he becomes them. Among the highlights of his latest album Is It Something I Said? (Reprise Records) are the character “Mudbone,” who sits ’round the barbeque pit, spittin’ tobacco in a can and tells outrageous stories about how and why he fled Mississippi and some side-splitting stories about a man whose Louisiana woman put a “fix” on him and the voodoo woman who cures him. Pryor has the magic of old radio shows when it comes to the audience’s visualizing a situation.

Beneath Pryor’s cloak of humor is that dagger of truth about ourselves, the society we live in, our idiosyncrasies, the roles we play to survive, and all the little human things we don’t always want to deal with realistically. An evening with Richard Pryor can be exhilarating or horrendous, depending on how uptight one is and who one happens to be sitting next to — lover or stranger. Pryor has gathered his street education and molded it into a special art form. And behind every work of art, the creator has his own philosophy about his motivations. Pryor has taken an innate part of Black culture — perhaps an unwritten subculture that many may not find valuable, plausible, or quite understand or accept — and presented it to the world in his own style. Television and segments of Black and White middle America may not be quite ready for Pryor in the raw, but then again they may not be ready for the truth, either. And that is Pryor’s platform — the honest but low-down, dirty truth.

In his personal life, Pryor is a realist and a sensitive, philosophical man more serious than one might believe. He is adamant about projecting his own personal image offstage as “just another street nigger.” But he’s come a long way from Peoria, Illinois. He is no longer fatmouthing with the boys on the corner, stealing, hustling, or being just another face in the crowd of comics. He’s a genius in the written and verbal world of comedy. Pryor is concerned about more than just his own survival and self-preservation; his concern takes in the survival of all Blacks. He contemplates the meaning of life itself; where man actually came from, what man’s purpose is here, and how Black people, who built the pyramids and did brain surgery in Egypt while Whites lived in caves in Europe, have declined to the state they are in today. His image may be of a concerned “street nigger” but, Richard Pryor is initially shy and guarded about himself on a one-to-one basis.

“I’m not trying to tell people any jokes but I sure like to make people laugh. That’s acceptance for me.”

One of the most sought-after comedian writers in the business, Pryor is warm and friendly until asked a direct question. When asked about the source of the material on his album, he sardonically queries. “Do we have to talk about this now?” and then grins sheepishly like a welfare recipient who wants the check but doesn’t want to go through any changes with a nosy social worker. “I hate to do interviews,” he continues and a day and night of hanging-out together passes before getting it together. “It would be nice if you had eight tape recorders that you could leave on in each room and record us just rapping naturally. Black people speak in shorthand. They know a language that no one else knows. We know things like bees and ants. To talk about comedy is so abstract — to talk about what I do — l just do it. I like to talk about all that is happening in the world. On stage I do it in a comic vein but I’m a serious person. I’m not trying to tell people any jokes but I sure like to make people laugh. And that’s acceptance for me.”

There’s an embarrassing pause as the only man who has ever sold over two-million-dollars-worth of an X-rated album, That Nigger’s Crazy, stares at the television set that is on but from which no sound is audible. Another side of Pryor’s magic is at work as his manager Bill Cherry and Pryor’s friend Deborah Jean “don’t be so mean” look on. He creates a spellbinding air of tension and then disperses it. “Why are your fingernails so large, nigger? You play piano or somethin’?” The room is filled with laughter as Pryor relaxes everyone. “I was a shy kid. I’m still shy. I get my feelings hurt easily,” he admits with a look that says, now I dare you to try me, and once again hysterical laughter peals throughout the suite. “You sure you don’ t play piano? I mean, it’s cool. In my neighborhood whatever you were was cool. You could be a thief, murderer, or closet queen. There was a faggot named Booie that turned more tricks on my block than the prostitutes but nobody ridiculed him. Dudes avoided him during the day but could be seen creepin’ around his house late at night. It didn’t matter. We were all part of a community. If a person was a thief you knew not to let him in your house, but to buy something from him was no big thing. Being a pimp was a form of employment. But people that had jobs as janitors or factory workers were starting a caste system. I was dirty-rat thief myself and could lie like hell.”

Richard Pryor was born on December 1, 1940 in Peoria, Illinois. His parents were divorced when he was five, which is when his acting career began. “I had to sit on the witness stand and decide who I wanted to live with. It was an act because I didn’t want to live on a farm with my mother and I was under a lot of political pressure from my grandmother. So I chose my father.” At age nine, Pryor was tending bar and running errands in his grandmother’s brothel. “My first job was working with the prostitutes. I would go through the house in the morning with a list of ‘unmentionables’ to pick up. They gave me big tips. Even the pimps were generous. In the winter my grandmother would feed the soldiers liquor and turn up the heat in the house so that they would fall asleep. Then I would unzip their Paratrooper boots and take the money they had stashed there. I later became a trick-getter.”

In his leisure, Pryor went to the movies and mentally made love to all the leading ladies. “That’s why one of my hands is larger than the other,” he confesses. He was fascinated by a comedy team named Dutch and the Dutchess that appeared at a strip joint in Peoria wearing mohair suits and earning $600 a week. “I was really impressed with their tall tales about New York, Chicago and Europe. You don’t know how you get a sense of humor,” he muses, ”but I tell this story and it’s really true. My Uncle Dickie brought me a cowboy suit. I was in the front yard playing and fell in some dog droppings. When I got up, everybody on the porch was laughing. The more I fell, the more they laughed. My father and his friends were comedians of a sort, also. On Saturdays when the pimps got off work at the Caterpillar tractor company they would be all dressed up and my father and his friends would be sitting on the porch. In the yard was lots of mud and when a pimp passed, they would invite him in and throw him down in the mud. Then that pimp would join them in tricking another one into coming in the yard.”

Pryor can use the smallest incidents as material. They do not work in print but when he expresses them they hyperventilate with humor. “Comedy is when you are driving along and see a couple of dudes and one is in trouble with the others and he’s trying to talk his way out of it. You say, oh boy, they got him, and laugh. But I cannot tell jokes. Black people go prepared to see other comics, but I don’t think they come looking for a typical comic when they come to see me. I’m not part of a package deal. I’m not a ha-ha-he-he comic. I might do anything and it’s fun for us. My comedy is not comedy as society has defined it. You can’t put your hand over it and lock me in. I would rather quit and go back to school.”

School for Pryor was typical for many bright Black children who would not conform to the regimentation of a classroom. Prankster Pryor went to a special school “because everybody thought I was retarded, including myself. Kids in my class couldn’t even talk. I was glad when the teacher would ask somebody to say the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag. That took up a whole hour and class would be over when I woke up. Pryor attended Central High School in Peoria, earned his varsity letters as halfback in football and center and forward playing basketball. All the time, his reputation as a practical joker grew. “I once tried to flush a girl’s head down the toilet. I guess that’s why they thought I was retarded in the first place.” After school, Pryor worked at odd jobs, packaging beef at a meat packing plant, racking balls in his grandfather’s billiard parlor, and driving trucks for his father’s construction firm. After graduation he enlisted in the army. In 1960 he was discharged and made his professional debut as an emcee in a small Canadian night club.

“I used to do things that were unnatural so I had to worry about my work. I was doing Bill Cosby’s material and I was jealous.”

Pryor pauses and his mood shifts. “I was always funny as a kid trying to be like other people. I always figured that nobody liked me so I tried to be like other people. Do I have to be telling jokes to make this article work? I got sentenced to ten days in jail by the Internal Revenue Service. The man sitting next to me got sentenced to 15 years. He said to me, ‘Lookahere, bro, take it easy, Richard. You’ll be all right.’ I looked at him and cried. He just got sentenced 15 years and tells me to take it easy, to be cool. How do you explain that? I know one thing, if you ever go to jail and some dude gives you the eye, just start fighting even if you know you are going to lose. Because if you don’t, the only thing that’s next is eye lashes, make-up, and pantyhose.” Pryor reflects and is serious again. “They are waiting on Nixon in jail. Yessir. What is justice? Nixon took justice and broke its jaw. Now, that is profane. People say I use too much profanity. There is no such thing as profanity in what I do. I talk lo people in their own words. When I say mother so-and-so, people react because they know exactly what I mean. This is our language. A lie is profanity. A lie is the worst thing in the world. Art is the ability to tell the truth, especially about oneself. Of course that takes a lot of courage.”

Pryor earned his courage and his ability to tell the truth on stage, and not overnight. In the beginning, he faked it. He was always humorous but his material was coming from another direction. “My comedy is special today because Black people made it special,” he says. “I started out in little dinky clubs and Blacks were the first to fire me. ‘You can’t talk like this,’ they would say to me. But White folks loved it. I built up a reputation in the White circuit first. If I had started out as a comic doing what I do now, I would never have made it. There is a lot of competition out here but I never had to compete with anyone else’s work. l compete with myself. I know there are others trying to follow me now. But earlier, I used to do things that were unnatural so I had to worry about my work. I was doing Bill Cosby’s material and I was jealous. ‘Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, ha ha, you know, a funny thing happened,’ but that wasn’t me. ‘You’ll love this one, he he.’ I was off into that and it really wasn’t me.”

During those years, Pryor appeared regularly at small Greenwich Village spots such as the Gaslight, Cafe Wha?, and the Village Gate. During the mid 1950s he began to appear on the Ed Sullivan, Merv Griffin, and Johnny Carson shows. He was a smashing success in Las Vegas but his audience was predominantly White and his material was not really what he wanted it to be.

“So I quit television. I quit because I didn’t want them to fire me. I’m that bold. I could see the firing coming. l could see the truck drive up with my check and the pink slip. But before it parked, I was out of there. I had learned. I know what I have to do today. I don’t have to look out for and back off the audience. I’m the baddest out there. I don’t need the stage. When I have to say, ‘Thank you for coming, good evening and good night,’ I have not done what I do. When I do something that is magic I know how people are supposed to react. I am vain enough to know, If my stuff doesn’t come like I know it should, then nobody can tell me different; that it’s funny when it isn’t. I can tell the real laughter from the surface ha ha has. I make people laugh and if I don’t do that, then I have failed. Trying to be funny is the worst thing in the world. I have to be natural.” And Pryor has that natural ability to touch on someone’s guilt feelings, his hidden thoughts, or some experience a person might have tossed to the back of his mind. He has the power to stimulate a gut reaction in his audience, causing people to laugh in spite of themselves.

“I know what I have to do because I’ve been in the business long enough. You know the tricks, how to coast and all. I have my nights but I can handle it. I just do things quick. For some it brings the eagle; for others it brings the crow — wrinkles. I know that I am not going to stop doing what I do because they haven’t shown me the monster in the basement of the White House. And we all know that one is there.”

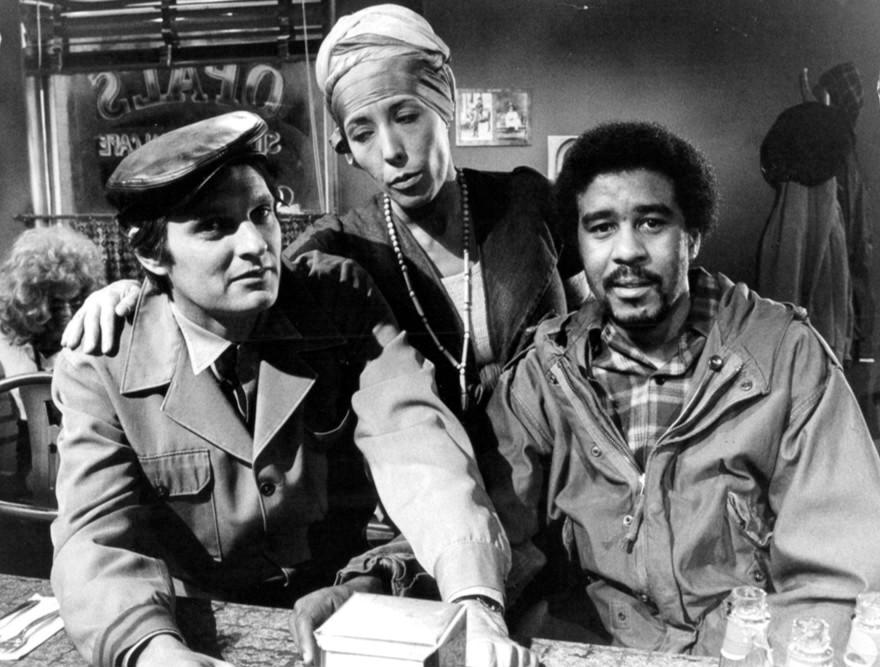

Twenty-six years after his “day in court,” Pryor resumed his acting career and starred as Piano Man opposite Diana Ross in Lady Sings The Blues. A serious side of the comedian was seen for the first time. Public acclaim led to more important roles in six other movies, including Hit! with his sidekick Billy Dee Williams, Wattstax, and Uptown Saturday Night. In 1973 his creativity was tapped further. Richard Pryor wrote scripts for Sanford and Son and The Flip Wilson Show. He collaborated with Lily Tomlin on two television specials and in 1974 received the American Writers Guild Award for Blazing Saddles which he helped write, the American Academy of Humor Awards for the same movie, and Lily. The album That Nigger’s Crazy earned him a Grammy Award and certified gold and platinum records. For that album he also received Record World’s honors for the Comedy Album of the Year. Earlier this year, the National Association of Television and Radio Announcers presented Pryor with their award for Comedian of the Year. He has completed a film with James Earl Jones, Bingo Long and the Traveling All Stars and Motor Kings, and has begun shooting Adios, Amigos.

When Pryor is not relaxing in his Los Angeles home eating cheeseburgers and watching television or flying to his estate in Barbados in his private jet, he and his manager are on the road doing what he does naturally. “Richard is a genius,” declares musician Miles Davis, who has known him many years. “He’s funny and serious with it. He’s more secure than he used to be and that’s a good sign because he’s under a lot of pressure and he’s got too much to offer to sweat the small stuff.”

Meanwhile, Pryor still searches to express himself and to find answers to questions he may never answer. He compares his life to that image of a court jester. “The symbol of comedy is the court jester. Look at the joker when you pull out a deck of cards. He balances himself on one foot. He teeters on jest and lives by his wit. You have to have a sense of humor in order to survive. My work is funny but it’s serious. I know what Black people think and expect. If I hadn’t mentioned Ford’s attempted assassination last night in the show, the audience would have been disappointed. I’m Black always. I can’t grow out of that and I don’t have to go back to the ghetto to get regenerated to know it. I’ve been there. All I have to do is go forward in myself as a man. We as Black people can survive anything. We think the worst and hope for the best. Jews lament about their 6 million being slaughtered in Europe. What about 190,000,000 slaves kicked out the bottom of boats trying not to get here?

“Christianity teaches us that the man who talks to God is the baddest dude out here. But what about the common man? I see Jesus and Mohammed every day. I see people who are humane, too. But we are surrounded by lies. Even the Liberty Bell cracked. Nature and its elements refused to accept that lie. But everything is subject to change. If free enterprise doesn’t work for White folks, or if niggers get too much money, they’ll change the money. But we can survive anything. And there is comedy in that.”

[Photo Credit: Wiki Media Commons]