For sheer emotional impact, the two movies that struck a deep societal chord over the last decade were Death Wish and Rocky. The first is easy to fathom. Charles Bronson (if he’s frightened, we’re not paranoid) cinematically revenged the indignities of our police locks, barred windows, electronic burglary devices, Doberman pinschers—not to mention our chagrin over the failure of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. Indeed, Death Wish might be viewed as the first promo for the Reagan years.

On the surface, the immense critical and financial success of Rocky is harder to plumb. At its least offensive, it was a mindless, derivative piece of hokum that back-pedaled from logic with more éclat than Billy Conn’s scampering for twelve rounds against Joe Louis.

The film’s creator, Sylvester Stallone, blatantly boosted from Brando in On the Waterfront—not only in accent and mannerisms but also because Rocky, like Brando’s ex-pug longshoreman, wanted to ascend from bumhood. The love interest of Rocky and Adrian (Talia Shire) bowed to the two sexual schleppers in Paddy Chayefsky’s Marty. The golden cliché in Rocky was from the archives: the mousy Adrian having her glasses removed by Stallone and the wallflower blossoming into a Venus flytrap. The daring of Stallone as a filmmaker is that he is beyond embarrassment.

The prizefighting aspects of the film were awash in bathos. Those who follow the sport know it is controlled by a handful of promoters, the networks, and the cash of gambling casinos and countries on the make which have dubious governments. Recent heavyweight fights have been a constant at Vegas’s Caesar’s Palace, because the high-rollers who arrive subsidize the purses. The week of the Ali–Larry Holmes fight marked the biggest take in casino history in Vegas.

The other sites for heavyweight fights have been in such bastions of democracy as Zaire, Manila, Kuala Lumpur, and Praetoria, South Africa. In short, the game is controlled by fleshpots and despots.

Yet we, the audience, were asked to believe that the cinematic Rocky (with no connections) was tapped to fight for the heavyweight crown after a mediocre career of mixing it up in church smokers. Since Hollywood often demands that we leave our brains at the popcorn counter, let’s for a moment accept this. There is a thin premise here, since Muhammad Ali (on whom the champion, Apollo Creed, is based) fought lesser local lights in his day. But the difference is that in reality Ali’s opponents were all part of the corporate hustle. First off, Ali’s hand-picked opponents needed to fill strict prerequisites. They would be underdogs to a flower child (unlike that magnificence of mayhem, Rocky); unlike Rocky, they would never be punchers (bangers) but cream-puff hitters (Jean-Pierre Coopman, Joe Bugner, Rudi Luebers, Karl Mildenberg, etc.) And like many of the aforementioned pacifists, they would have a connection—usually a foreign country shilling for them and guaranteeing a lucrative and easy payday for Ali. The government payday for staging Ali was that the world would see the host nation exhibiting clean and open sport, thus belying its well-earned ranking for human-rights violations.

Let’s grant Stallone the latitude that Apollo né Ali would give a local turkey a title shot, ignorant of the challenger’s granite chin and awesome punching power. Truth is always messy to commercialism anyway. If Evita could be transformed into a Madonna, it’s little to ask that Ali play the fool. But the major difference (besides evading punchers) was that Ali always perfumed the cabbages he chose. It was Ali’s wont to find qualities in his opponents no one else in the boxing community had noticed. Pitty-pat punchers became closet Dempseys, incredible hulks were bestowed Astairean agility, and well-behaved black men were alchemized into honky tools of the establishment. All this was done for the most exalted of reasons: loot.

But nothing ever seems to satisfy Stallone. In his version, the challenger, Rocky, is exiled by the champion to punch sides of meat in a packing house (accenting his power?), to work out in clothes that look as if they were aged in muscatel, and to do his running on concrete streets, a regime verboten even to the Golden Glovers. Training expenses were just another bit of reality that got mugged.

The daring of Stallone as a filmmaker is that he is beyond embarrassment.

The fight in Rocky is another example of Stallone’s playing fast and loose with a basic truth. Indeed, sometimes champions take challengers too lightly, and they find themselves in deep. But this always occurs late in the fight when the champion, unable to take out the challenger, tires. In Rocky, the challenger starts to whale the champion early. If this unlikely event occurred to a champion of the Creed-Ali caliber, the gross underestimation would be readily corrected, and the champion would savage the said opponent. It should be noted that when Ali returned to the ring (after being banned for three-and-a-half years for refusing draft induction) to fight Jerry Quarry—a very legitimate contender, not a church-smoker pug—Ali very wisely suspected his own condition. Thus, he immediately went after Quarry and stopped him in three rounds.

All this might be considered insiders’ privy knowledge from which the movie fan is exempt. But it doesn’t answer why the same movie fan would devour this marzipan after sampling such films as The Champion, Body and Soul, The Set-Up, and Fat City. These films certainly had their moments of melodramatic license, but they also had the cynical accuracy and taste to realize that the Marquis of Queensbury had been replaced by the Marquis de Sade as the sport’s patron saint.

Even the most casual surveyors of the sports pages and watchers of the evening news realize that boxing machinations—illegally signing other promoters’ fighters, engineering the ratings and records to satisfy network tournament requirements, promoters allowing damaged fighters to compete—have resulted in more lawsuits than the proverbial whiplash.

Well, then, perhaps what charmed the Rocky audiences was the film’s original portrayal of the working class. A case cannot be made for this point of view either, since Rocky’s view of the proletariat is a continuum of Hollywood’s and television’s cultural genocide of the blue-collar class. “Dems,” “doses,” and grunts abound, giving rise to the notion that working people induce hernias by their speech. Though this class is always depicted as having a flair for violence, they are rather impotent figures with simplistic dreams: childlike patriotism, a religious belief in God and capitalism (the “American way”), a devotion to the old bootstrap theory, and a firm belief that simple folk may own little in the way of worldly goods but are the sole possessors of hearts of gold. Social anger never enters their world except to be directed at those who expect “a free ride” (read: minorities), à la Joe and Archie Bunker.

You could say that the glitter Goebbelses of Hollywood and television would be high on Karl Marx’s enemies list, but that is importing outside help. It is enough to remain domestic and cite the fact that the American labor movement—which was responsible for some of the most progressive legislation in the areas of race, health, education, and welfare—would find the depiction of their ranks an abomination. To the entertainment industry, Joe Hill, John L. Lewis, Harry Bridges, Walter Reuther, and George Meany, as well as their worthy successors, have never existed. The celluloid indictment of Hollywood is that one can’t find an American equivalent of the class films of another industrial democracy, Britain: Look Back in Anger, Room at the Top, and the nonpareil Saturday Night, Sunday Morning.

So the driving engine of the success of Rocky has to be found elsewhere. The dark genius that lurks behind the Rocky phenomenon is casting Apollo Creed in the mold of Muhammad Ali. One doesn’t know if Stallone divined this darkness, or if the Creed character evolved simply because Ali was the most logical role model with his domination of both the fight game and our consciousness for so long. Motive is little matter. Race is the force of the original film and of the sequels, Rocky II and Rocky III.

Since Ali’s arrival on the scene (before his conversion to Islam), he was perceived as something new and dangerous. At first, he was merely a loudmouthed, sassy, cocky black, which translates into: he didn’t know his place. My first encounter with him was on a street corner in Los Angeles in the 60’s, where he was huckstering tickets to his fight with Alejandro Lavorante. He was a brash, funny kid shilling his gaudy estimate of himself. The passersby were incensed and told him, “You’re going to get your big mouth shut,” to which Ali (then Cassius Clay) responded that it would cost them only $15 to witness it. And out of pique, damned if they didn’t buy! Even then, Ali knew his destruction was worth Yankee dollars.

After he won the championship from Sonny Liston and announced his conversion to Islam (“Black Muslim!” the tabloids blared), the emotional coin for his demise skyrocketed. But the ultimate sin was yet to come: his refusal to be inducted into the Vietnam-era Army, when he spoke the soundest foreign policy of the time, “The Vietcong never done nothin’ to me.” With that move, not only did Ali desecrate the sacred patriotic image of Joe Louis, who had defeated Hitler’s Max Schmeling, but he also became the Pied Piper to millions of middle-class white kids. By then, the national bounty placed on Ali was limitless.

For a decade and a half, a large portion of America wanted Ali to be ground into the dust—not to be defeated, but to disappear. The contrary happened. When he won his crown back against George Foreman in Zaire with tactical brilliance, his station was so elevated it transcended boxing. He was a national figure who spoke out on anything that engaged him: He offered to use his clout with Muslim nations to quell Mideast and African tensions, and settle the hostage question with the Ayatollah. Publications pronounced him the most recognizable man (more so than the Pope) in the world. This was an unacceptable scenario. It befouled Peoria.

By the time Ali’s decline came, it was too late for joy. He was an old man, and like the rest of us had money problems. He no longer talked about “white blued-eyed devils,” and he was a safe talk-show guest. He lost his title and then won it again for an unprecedented third time against Leon Spinks in a lackluster fight. If anything, Spinks loomed more dangerous than Ali in our national psyche. “Neon Leon,” with his gap-toothed inarticulateness and his penchant for run-ins with the law, was a ghastly memo to urban neglect. Ali, for once, was preferable.

When Ali finally was trounced by Holmes, it was too painful to watch. He was a sad, fat old man, who had deluded himself with his press clippings, being mugged by a finely tuned athlete. And Holmes was black to boot, so Ali’s racial humiliation was averted. Yet even here, Ali maintained his dignity. Unlike other aging fighters, he refused to take an easy fall. He took Holmes’s unrelenting beating until the fight was stopped with Ali vanquished but erect. By now, everyone, regardless of political ideologies, wanted Ali to disappear. Not out of malice, but mercy.

Stallone is, wisely, a great believer in music. Since the acting in this trilogy has been so atrocious and the lines so limp, he has continually used emotional soundtracks to jolt and jerk his audiences.

Thus, our lust for revenge was denied until Stallone rewrote history. In Creed we had a young, trim, taunting, bellicose Ali. The public’s racial antagonism was rekindled, and the revenge was spiced by the fact that the instrument of our retribution was the white Rocky Balboa. Rocky would not only avenge the taunts and the societal criticisms of Ali, he would exonerate the role of the white warrior as well. The last white heavyweight champion was the Swede Ingemar Johansson, who won the title from Floyd Patterson in 1959, only to lose it back in their rematch in 1960. Since then, there had been an inept parade of “white hopes” who proved to be genetic embarrassments. The best the white fan could do was muster memory: “Argh, Marciano or Dempsey would have killed him.”

Of course, boxing only mirrored other sports in that the predominant figures were black. In a society where the whites control the property and the power, this could be seen as a minor irritant—except that as the world turned increasingly violent, and physical truculence seemed to be reaping rewards from neighborhoods to nations, the sports world became a dark metaphor.

So Rocky, for all its filmic crudity, bordered on a colonial restoration. The white man was no longer the hapless victim, the body gone slack, but the swashbuckler of yore. If one doubts this premise, simply and honestly test these equations to see if Rocky would maintain its emotional power: Would Rocky work if Apollo Creed was a white champion? If the film had intrinsic merit or the quality of art, couldn’t it survive a role reversal? How about Rocky as an underdog black challenger vs. a white champion? There isn’t a studio that would have bankrolled this version.

Besides our racial animosity, Rocky had another factor going for it. Near the end of his career Ali, like so many of those in the Sixties who used the media to expostulate their messages, was devoured by hype. He wore us out with his endless appearances and chastisements. He joined the company of Bella Abzug, Dr. Spock, Jane Fonda, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, and Gloria Steinem. Instead of electricity, he produced instant ennui. We began to suspect that to these people the media was not the message but the Messiah. They all seemed only a step above Jerry Lewis, who was so craven for attention he would show up on talk shows sporting false buck teeth.

So not only did the racial baiters have something to cheer about in Rocky, but also those who had become nauseated by sermonizing hype. The low ground was that Rocky was a white avenging angel; the high ground was that he was a censor with taste. After all, one man’s creed is often another man’s bullshit.

Yet, for all its flamboyant ingredients, Grand Guignol acting, recycling of golden oldies, and manipulative music, the original Rocky had energy and a modicum of restraint. Under director John Avildsen, the scenery was merely gnawed, not devoured, and Rocky, for all his spartan showing, did lose the fight to Creed (though barely). The film pulled back from the abyss. The rednecks were given only a pyrrhic victory. Logic, like the cavalry, arrived in the last reel.

It’s a shame the saga didn’t end there. But Stallone was unable to find success in any other guise, so Rocky was reduxed under his own scripting and direction. Rocky II, with its ludicrous ending of Rocky and Creed on the canvas in the fifteenth round, each struggling to beat the ten-count (Rocky Rises!) even had the kids, Hollywood’s target market, groaning. After that finale, one and all hoped Stallone would hang them up, since Rocky was not the champion, and his two bouts at the box-office had been boffo. Besides winning the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1976, Rocky and then Rocky II (1979) rank 22nd and 25th, respectively, on Variety’s list of all-time film rentals.

But in the interim, Stallone’s four other films, “F.I.S.T.,” Paradise Alley, Escape to Victory, and Nighthawks, went into the tank. So Rocky has been resurrected yet again to complete what Stallone says is his trilogy, and the less generous view as a three-round prelim.

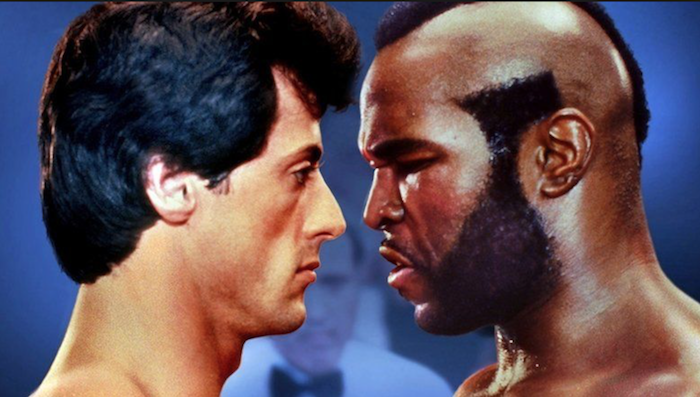

In Rocky III, as in Rocky II, Stallone plays triple-threat: actor-writer-director. If one had any hopes that the final chapter of the Stallone trinity would be elevated, that notion quickly disappears with the film’s opening scenes. Stallone-Rocky is seen in a montage flattening opponents in ten title defenses. To his credit, he does resist the flying calendar pages and the clicking train wheels of the pug pix of the Forties and Fifties. While Rocky is demolishing contenders, the camera pans in on a menacing black with a Mohican haircut in the fight crowd, who obviously scorns Rocky’s rough-housing. The film’s central theme is set: Rocky will have to make this malevolent cat cry “Uncas.”

To the fight camp follower, Stallone’s surly critic is disturbingly familiar, though the coiffure is wrong. His identity is revealed by scalping the dude, who is none other than the real life “Mr. T.,” formerly the boorish bodyguard of the aforementioned, short-lived champion, “Neon Leon” Spinks.

Whatever one’s estimate of Stallone as a moviemaker, at this point you’re moved to ponder whether Stallone is a Melvillean delver into the dark side of the American soul. Could it be that he fathomed Spinks was more reprehensible to us than Ali? After all, Ali, whatever message he was delivering, mirrored our middle-class mores. He was handsome, glib, and (when it struck him) courtly, as befit a well brought up, churchgoing child of Louisville. Spinks, a product of St. Louis’s rough public housing, lacked all this as well as orthodontia. A mouth such as Spinks’ would mortify us on Donahue.

The level of the movie is fixed in the next series of scenes. Rocky is shown doing an American Express commercial and an appearance on The Muppet Show. The audience with whom I saw the film chorded in delight at this juncture. Thank God! The film wouldn’t be beyond them. Rocky III resided in their orbital channel.

Mr. T. as “Clubber Lang” (ahh, the subtlety) is not to be confused with a two-dimensional villain. He continually directs epithets at Rocky’s skills and virility. It is a performance of unrelieved rage. And when Clubber really works himself up (which is constantly), he resorts to unintelligible growling, snorting, and grinding of teeth. The latter grants him more virtuosity than his former benefactor, Mr. Spinks. There is no doubt about it: Clubber is a cat who could empty a subway car quicker than a flasher.

On the side of divinity we see Rocky cooing with wife Adrian (Shire again) in nice Fifties fashion. The sweet, shy Adrian, whom Rocky discovered working in a pet store (St. Francis in drag?), must never be seen as blatantly sexual. Since the couple now has Rocky, Jr., we know she does it, but she cannot allow us to think she revels in it.

Rocky Jr. is sheer window dressing for Pop to bounce off. Rocky is seen reading him fairy tales in his estimable elocutionary fashion, and there is some parental hand-holding and the goodbye before Dad goes into training for the big fight. As a third wheel, the kid could have used the agent Cheetah had for the Tarzan series.

Burt Young also returns again as Rocky’s brother-in-law, Paulie. His main function seems to be allowing Rocky superiority of diction. After three films and his brother-in-law’s ten successful title defenses, Paulie has yet to find a new tailor or haberdasher. He is still scratching himself as if his native Philadelphia was a Tijuana cathouse.

But Paulie is given “dimension” in III. He is discontent because Rocky hasn’t looked out for him. While the champ resides in a gaudy house schlocked with mock provincial, he has bequeathed Paulie only an expensive watch, which Paulie smashes to the ground in anger. Instead of being hurt by Paulie’s allegation (as any street guy would), the corporate Rocky lectures Paulie on the danger of expecting handouts. After all, he, Rocky, went out and beat the odds, and the proper way is for all of us to do our own thing. The reconciliation with the pissed-off Paulie comes when brother-in-law offers him not a share of the swag but a job working the champ’s corner. Paulie, contrite but effusive, accepts. Score that round for David Stockman.

Paulie, of course, like the rest of the white underclass in the film, is Hummel figure adorable. When Mom and Pop are out, and Paulie is babysitting, he and Rocky Jr. (in the best Runyon-mawkish tradition) dope the Racing Form.

The domestic side established, the film moves on to its major themes. Rocky, still dodging the slings and arrows of Clubber, enters a wrestling exhibition with one “Thunderlips.” Thunderlips sees himself as the consummate male and is attended by a bevy of adoring beauties in the ring. Like Clubber, Thunderlips badmouths Rocky’s manhood until one is led to believe the only rising Rocky does is from the canvas. With the wrestler, Stallone is again shilling Ali’s legend in that Ali had an exhibition with a Japanese wrestler for a reported million-dollar purse. Again the truth in the film ends with that basic fact.

The Ali exhibition was choreographed for the Japanese mat champ to win, until Ali blew the ending when he announced it at an airport press conference on his arrival in Tokyo. The Japanese, who took this hokum seriously (Godzilla movies deaden credulity), became incensed, and the match ended up in an honest, tedious draw with the grappler lying on the floor for the majority of the fight and kicking at Ali’s legs, trying to trip him.

Rocky takes on Thunderlips for charity, much against the wishes of his trainer Mickey (Burgess Meredith). Mickey exclaims nobody would fight such a monster for charity. Rocky responds, “Bob Hope would,” and thus another note of recognition is struck. The celebrity screening audience got the gag. It meant they are on the inside, and poring over People magazine is redeemed. In Rocky you namedrop Bob Hope; in Woody Allen films cultural avatars. The only difference in audience mentality is McDonald’s vs. Elaine’s.

Thunderlips is not a believer in choreography, and he pummels Rocky with fists, elbows, and knees. After unsuccessfully trying to snap his spine, Thunderlips throws Rocky a few rows into the audience. Rocky, enraged, runs up the aisle, leaps back into the ring, and claps Thunder around, then throws him into the seats. If this is to be believed, watch for a sequel to Jim Jones.

But this is a minor storm. The big bang has to be the endless needler Clubber. Clubber finally has his way when he attends a dedication of a public statue of Rocky by the Philadelphia city fathers. The accuracy of this scene can be disputed, since ex-Phillies pitcher Bo Belinsky said that it was a burg that booed parades. Nonetheless, Clubber ruins the proceedings by first challenging Rocky and then coming on to Adrian, snarling that it must be tough living with half a man. When Clubber invites Adrian to share his cave, Rocky has had enough. It’s time to get it on.

But we have a plot twist. Mickey, the gnarled old trainer, tells Rocky that he doesn’t want the fight because Rocky isn’t “hungry” anymore. He then confesses he has picked the opponents for Rocky’s ten title defenses. The ten weren’t hungry either. Meredith, whose mangled, tortured speech makes Stallone and Young seem like Lincoln and Douglas, explains this all-consuming famine by saying that Rocky is suffering from the worst thing that can happen to a fighter: “You got civilized.” The best laugh in the movie didn’t get a titter.

When Rocky convinces Mickey he will retrieve the lean and hungry look, abandon post (Emily) and return to pillory, Mickey agrees to train him for one more fight.

On fight night incredulity main events once more. In professional championship fights the contestants always enter from different sides of the arena, respectful intervals apart, so that each fighter can milk his claque. This is orchestrated via walkie-talkies from the promoter’s aides at ringside. In Rocky III, as Rocky exits his dressing room, Clubber is coming down a flight of stairs directly in Rocky’s path. Both fighters are heading for the same tunnel at the same time! Or course, the anti-social Clubber starts badmouthing, and a skirmish begins. Mickey moves to intercede, and he is hurtled aside. We see Meredith clutching his chest and turning puce. He is either dying from a heart attack or reaching for a complex sentence. Alas, he is dying, and cinematic subtlety in acting will now be the sole province of Jack Palance. One doesn’t know if the cheering heard is from the expectant crowd in the arena or the grateful Stanislavsky in heaven.

Rocky, with Mickey fading, goes on alone to be thrashed quickly by Clubber. He returns to his dressing room in time to render the slipping Mickey a rosy outcome of the fight. A lie, to be sure, but a kindly one for the road.

Rocky, who has always blessed himself before combat, is then seen attending a Jewish burial service for Mickey. Rocky might have lost, but Mecca, which is now so prevalent in boxing, has taken a drubbing.

Of course, Rocky has now lost all self-esteem. He is so down on himself he rediscovers his roots and resorts to the conduct of a native Philadelphian. Late at night, from his motorcycle, he throws his crash helmet at his statue in the civic plaza.

Help then comes from an odd but familiar quarter. Apollo Creed, whom we have seen as a color commentator at the fight, approaches Rocky with the secret of how to beat Lang. He will train Rocky for the rematch. Creed (Carl Weathers) tells Rocky he has lost the look, “The Eye of the Tiger” he had when he met Creed. This serves a dual purpose: showing that blacks even have more rhythm in speech, and introducing a rock song, “Eye of the Tiger,” performed by Survivor.

Though Creed knows the secret, it is never explained why he doesn’t challenge Clubber. And in early training sessions with Rocky, Apollo makes Rocky look like a chump. Yet Creed has retired for some mysterious reason, confounding to students of the sweet science but not to showbiz clockers. Second bananas don’t carry pictures.

Creed, like Mickey, insists Rocky return to his beginnings, but then we are perversely returned not to Rocky’s but Creed’s beginnings in an all-black gym in south Los Angeles. This gives Paulie a chance for a few yuks at the expense of the neighborhood (“I don’t have a gun”) and at the gym’s training regimen (“Rocky can’t move to that jungle music”).

It seems that Creed’s plan is to transform the mauler Rocky into a ring dandy in the interim between bouts—Marciano into Ali on the three-month plan. In Rocky II Stallone switched from southpaw to righty to beat Creed. Stallone, a fine physical specimen, fancies himself a boxing buff, but his ideas about prizefighting (if they’re truly rendered) equate with those of a small child’s. “Secret weapons” win fights; gimmicks, not craft, make great fighters.

So Rocky is put through muscle-stretching exercises, sessions in swimming pools, and aerobic dancing to unknot his puncher’s muscles and make him loose and limber, a black-style fighter. Creed is a patient, loving trainer, and all this might be Stallone’s apology to Ali for so shamelessly bastardizing his legend. After counting the box office, a mea culpa of “Black Is Beautiful.”

But Stallone is never content. Bad enough we must buy the premise of the bear learning to dance, he also asks us to believe that Creed insists Rocky not only train in a slum but live in one as well. The former champion and his wife are ensconced in a flophouse near the gym, complete with sterno-drinkers and the Degas tableau of Adrian performing her toilette over a minute wash basin, the only bathing facility in the one-room flop. It is a breakthrough in fight films—the audience suffers the brain damage. For all his faithful ministrations, Creed asks little: only that Rocky wear Creed’s American flag trunks into the ring plus a favor to be named later. Rocky is touched by the former and curiously amused by the latter.

After two films, Stallone must have figured the Rocky theme was growing stale. Stallone is, wisely, a great believer in music. Since the acting in this trilogy has been so atrocious and the lines so limp, he has continually used emotional soundtracks to jolt and jerk his audiences. Here, as Rocky enters the ring, Stallone resurrects George M. Cohan, and the “Marine Hymn” blares.

Needless to say, Rocky is successful in his quest. His punches land like howitzers, and as in I and II the referees and the ring doctor are off on another set.

After the victory, Creed’s favor is divulged. In the final shot (some time later) Creed and Rocky are seen in full pugilistic regalia entering a ring in an empty gym or in Rocky’s basement (it’s not clear). Apollo wants one more shot at Rocky sans audience. The men square off, Rocky throws a left, Creed counters with a right, and the frame freezes.

The dark specter is that this ending, Stallone’s pronouncements aside, is a natural segue to a sequel. If so, the unfathomable depths of eternal damnation begin to assume definable dimensions.