I’m standing outside an imposing four-story graystone townhouse. Located on a leafy, blossoming block of East 94th Street in Manhattan, it’s the headquarters and worship center of the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Society, the spiritual home to J.D. Salinger during his mystifying Silent Years. The home to his late guru, Swami Nikhilananda, a name I’m sure you know but one I only just learned from reading some Salinger letters recently donated to the Morgan Library by the swamis from the Center here.

Not those letters—the ones that got the most media attention recently—a cache of charmingly flirtatious missives Salinger wrote to a young woman in Toronto in the early ’40s, when he was just getting his stories published, before he shipped out for infantry combat in Europe. They got most of the attention for their gossipy content (inside stuff about The New Yorker!).

No, I’m speaking of the other cache of newly acquired letters at the Morgan, which the Times didn’t even mention: the deeply serious, spiritually oriented letters Salinger wrote to the swamis here, donated to the library just a month before the flirty ones. They didn’t make as much of a splash, but to my mind they go to the heart of the matter, the heart of Salinger’s mind. They testify to the state of Salinger’s soul in his Silent Years: the half-century or so following the explosive mid-’50s success of The Catcher in the Rye, when he retreated from the world, secreted himself on a hidden hilltop cottage above a tiny New Hampshire town, stopped responding to an ever more demanding and feverish fanhood and press. Retreated aesthetically into an ever more hermetic fictional universe that diminished to the dimensions of an Upper West Side apartment inhabited by a super-precocious family named Glass whose increasingly narrowed focus was on the oldest of seven children, the mystical windbag and spiritual suicide, Seymour. Increasingly incoherent fictions clogged with a smorgasbord of half-digested chunks of Eastern mysticism. Culminating in his Finnegans Wake, the last story he published while alive, “Hapworth 6, 1924,” a story that appeared in The New Yorker in 1965 and was followed by 45 years of not publishing. Though apparently still writing but denying to the world whatever it was he’d written.

Could he have realized he had painted himself into a corner with his incessant, increasingly verbose, even frantic attempts to badger us into believing in the seer-like wisdom of Seymour Glass? The struggle to anoint Seymour as Holy Man incarnate seemed to reach a peak of ludicrous fervor in that final “Hapworth” story, which consisted, in the main, of a 25,000-word “letter from camp” purportedly written by 7-year-old Seymour, parading an impossible erudition and supposedly giving us the full flavor of his prodigious wisdom and spiritual prodigality.

That was what was so tantalizing about all the rumors about the never-seen ghost manuscripts Salinger supposedly produced in the Silent Years, when he was said to be working steadily. In an email, his most recent biographer, Kenneth Slawenski, told me he believes Salinger completed, or nearly completed, at least two novels. Letters and memoirs have depicted Salinger adhering to a dawn-’til-dusk writing schedule all those years with the typewritten pages said to be piled up in a vault somewhere.

Tantalizing because they raise the question: Was Salinger struggling for 45 years to paint himself out of that corner, to extricate himself from Seymour worship? Or was he painting himself further and further in, trying to make Seymour live up to his impossible billing?

Were the ghost manuscripts straight out of The Shining: “All work and no play makes Seymour a dull boy”? (Could Seymour possibly be more dull than he already is?) I’d been tracking the question of the ghost manuscripts—do they exist, will they ever see the light of day—for some time. And recent developments put me back on the case, this time with a new approach. A direct appeal, like the one I used with the Nabokov estate.

My renewed interest began with an email request from the writer Thomas Beller who, in the course of completing his biography of Salinger had come upon my most recent Slate story on Salinger and asked me for the URL of a now-defunct Hungarian website that had once hosted some of Salinger’s early uncollected stories, which I got to read before the site was taken down. Salinger had long sought to disappear what he considered his imperfect early work. (I still had the Hungarian URL, now 404-ed.) Beller and I discussed the question of whether one of those stories “Go See Eddie”—no longer available—might have portended a road not taken in Salinger’s fiction.

A more sexy direction, perhaps, as suggested by Renata Adler in a memoir in which she recounted Salinger telling her that he stopped writing for The New Yorker because he wanted to write more about sex and he believed William Shawn was too puritanical to countenance it in his pages. (I believe Adler’s story; anyway, I like the idea of Salinger writing about sex—as long as it’s not Seymour sex).

And then there were the reports of a forthcoming Salinger documentary (and associated book), which promised new “revelations.” And finally, I learned about—and read—the overlooked Morgan Library Swami letters, which led me here, to the sidewalk outside the Ramakrishna Center. And left me with a dilemma: Would I be, in effect, spying on Salinger’s departed soul by entering into his swami’s domain for the worship service about to begin?

Whatever it was Salinger found inside the swamis’ townhouse may have eased his suffering, but his late work, it seems to me, suffered from it all. His late work might well be regarded as a casualty of war, literary PTSD.

I had learned to be careful with the wishes of departed literary eminences. My initial purpose in going to the Morgan, where I encountered the swami letters, was to seek to do for the Salinger estate what I had done for the Vladimir Nabokov estate. Slate readers might recall the series of stories I wrote to persuade the late writer’s son Dmitri to cease his three decades of dithering and finally make a decision as to whether he would burn his father’s last incomplete draft of a novel (The Original of Laura) as his father had instructed him—or publish it. (By the time Dmitri went ahead and published it and thanked me in the acknowledgements for the campaign I’d waged, I had decided it was a mistake; he should have burned it.)

The Salinger estate would be a tougher nut to crack. “Dear Mr. Rosenbaum, I do not answer questions about J.D. Salinger,” his longtime literary agent Phyllis Westberg responded curtly to my email inquiry about what Salinger might have left behind. That’s more than I got from his son Matthew, an executor of the estate along with Salinger’s widow Colleen, who didn’t respond to the email I had asked his agent to forward.

I wish they would realize that if they truly cared about Salinger’s legacy they would allow us at least to know he hadn’t devolved into utter incoherence in the Silent Years. Tell us whether there was readable material left behind, even if the author had instructed it not be published for 50 or 500 years. Ideally, offer us something. They may well be under instructions from beyond the grave and under instructions not to reveal the instructions. I don’t deny they are in an unenviable position. But I believe that their utter silence in the three and a half years since his death is now verging on a scandal that does a disservice to the writer.

An announcement that there would be more Salinger to come would at least cause critics to suspend judgment about whether the late stories are the lamentable lens through which to look at his work. Otherwise he is liable to be downgraded to a one-hit wonder, his Catcher a kind of Catch-22 phenomenon.

With little hope of hearing anything from the estate, I decided to look further into the question of what the hell was going on—or what hell was going on—in Salinger’s mind during the Silent Years, one of the great literary enigmas in America letters.

Which is what brought me here on this perfectly cloudless, insanely blue-skied day on a thrilling spring morning. A perfect day for bananafish, you might say if you were the suicidally minded saint Seymour in the Salinger story of that name (in Nine Stories, the collection with the Zen koan epigraph—“What is the sound of one hand clapping?”—that signaled Salinger’s mystical turn). I’m not suicidally minded but I’m troubled. Should I stay or should I go? Should I enter and attend the worship service of the Ramakrishna Center, the very center of Salinger’s spiritual life? Or would that cross some line, be a kind of metaphysical/theological espionage? This is the dilemma Salinger’s half-century retreat has always posed, for readers, biographers, critics.

I was tempted to cross the line because the cache of Salinger letters written to this address in the Morgan answers a question left hanging by his most recent biographer. From Kenneth Slawenski’s impressively researched biography we learn that “after returning home from [wartime combat in] Europe he began to frequent the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center on East 94th Street, around the corner from his parents’ apartment on Park Avenue, which taught a form of Eastern philosophy centered on the Hindu Vedas, called Vedanta. There, Salinger was introduced to The Gospels of Sri Ramakrishna, a huge volume of complicated religious doctrine that explicitly advocated sexual restraint.”

Curiously, Slawenski chooses to connect the dots here to Salinger’s sex life at the time (of course, he ultimately married thrice and had two children) rather than to what “Europe” meant to him, the bloody inferno of post-Normandy combat that led to a kind of nervous breakdown in the aftermath of which he apparently sought solace from the swamis here. But until I read the Morgan letters it was not clear to me just how close and continuing his relationship was to the Ramakrishna swamis. Very close. A relationship that lasted throughout the Silent Years—the last letter at the Morgan is dated two years before his death.

And indeed the close connection to the swamis here revealed in the letters might have been responsible for the silence of those years. The Morgan letters make more clear than before what among the smorgasbord of Eastern mysticism was the main dish, what was the unifying thread? Now we are able to say it was the Ramakrishna brand of Vedanta that had engaged him most personally and most deeply. Now we are able to name the swami whose counsel he most relied upon. Someone who took too seriously the swami’s injunctions against worldly striving might just have decided, ultimately, to write only for the eyes of God.

In the earliest letter, Salinger tells Swami Nikhilananda how he’s looking forward to reading the latter’s book, Man in Search of Immortality, a subject he says is dear to his heart, and offers the swami homeopathic advice. (The estate allows paraphrasing the content of the letters but no quotation without express permission.) In another letter to another swami he raves about a book called Vital Steps Toward Meditation, warns against sensual pleasure and the ultimate distraction—the Mind, that beast in the jungle. He laments the lack of a middle way between extreme asceticism’s distrust of the body and physical yoga’s over-intense absorption in it. And reminisces about the good old days hearing Swami N. read from the Upanishads at the Ramakrishna Center’s Cottage at Thousand Island Park in the St. Lawrence River. He talks about the way that he makes it a practice after he opens his eyes in the morning, but before his feet hit the floor, of reading from the Bhagavad-Gita. And on the material side, the Morgan cache includes copies of checks he regularly sent to the Center at Christmastime until very late in his life.

The saddest revelation about all this comes in another cache of letters at the Morgan I had not been aware of. These were written to Michael Mitchell, the artist who created the original cover illustration for The Catcher in the Rye. They span the Silent Years and capture the lost clarity, the wry urbanity of Salinger’s prose voice at its best. I’m surprised more hasn’t been made of them.

In one, Salinger is telling his lifelong friend his reaction to an incident famous in Salinger lore: the moment in the ’80s when he was captured by surprise by a New York Post photographer outside the Cornish Post Office. The picture, which the Post ran on its front page, shows Salinger’s absolutely agonized, angry, bitter face. It’s painful to look at, and in the letter he says it made him feel homicidal in his heart and hate humanity. But in a remarkable display of self-effacement he admits to his friend that a local Cornish girl who knew him well from seeing him around town had the temerity and the honesty to tell him, after seeing the Post photo, that, in fact, that was the way he looked almost all the time.

This is one of the saddest things I’ve read. What this suggests is that all his labor-intensive spiritual practice—the meditating, the yoga, the homeopathy, reading the Bhagavad-Gita every morning—didn’t make him happy, didn’t fill him with the bliss and joy in existence and feelings of love for his fellow humans, for the “fat lady” as the supposedly great revelation from Seymour at the end of “Zooey” had it.

So what did he find in this building, in Vedanta; what did he take away? What did he leave?

I think it’s important to be specific here, now that we have located Salinger on the spectrum of Eastern spirituality, just what beliefs that location entails. Because there has been so much random, ungrounded speculation based on the wide array of quotes from Eastern wisdom to be found in the later fiction that the actual Ground of Being of the writer has been obscured. And so here is the way the Ramakrishna Center defines the version of Vedanta Salinger’s Swami (Nikhilananda) inculcated: “Vedanta is the philosophy that has evolved from the teachings of the Vedas, which are a collection of ancient Indian scriptures—the world’s oldest religious writings. According to the Vedas ultimate reality is all-pervading, uncreated, self-luminous eternal spirit, the final cause of the universe, the power behind all tangible forces, the consciousness that animates all conscious beings.” This has a kind of purity and dignity, in effect portrays the universe itself as Ultimate Author of All, which may have posed a problem for an author seeking to believe in his own fictions.

I had my own problem standing on the sidewalk in front of the Ramakrishna Center townhouse as the worship service was about to begin: a sense of déjà vu. The long and winding road that led me to this door had, some years ago, led me to another liminal verge—the property line at the bottom of Salinger’s driveway in his semi-secret Fortress of Solitude I’d tracked down on a windy hill overlooking Cornish, N.H.

I had come there not to trespass but to celebrate that boundary, that invisible Wall that Salinger had erected to separate himself from the “publicity industrial complex.” To pay tribute to his silent reproof to the demands of celebrity culture as a kind of unwritten work of art in itself. Only to be rewarded by the roar of Salinger’s car as it backed down the driveway toward me, splattering me with inky sludge as it raced off down the rural route.

Would it be a similar symbolic trespass to cross into the realm of Vedanta that was his true secret hideout, into his spiritual Fortress of Solitude in the townhouse? I felt I had a reason this time: The inky sludge of Salinger’s late work made me want to cross the line. Made me want to experience something akin to what drew Salinger to the swamis, a lifelong relationship that began during his recovery from a post-war nervous breakdown that seems from our modern vantage point to be PTSD-related. (He checked himself into a hospital in Nuremberg, Germany, after going through the bloody grind that took him from Normandy to the battle of Hürtgen Forest in Germany.)

In “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” we learn that Seymour had a nervous breakdown after his wartime experience, a prelude to his suicide. And then there’s “Sergeant X” in “For Esme With Love and Squalor,” seen suffering PTSD symptoms after fighting his way through the Hürtgen Forest.

Whatever it was Salinger found inside the swamis’ townhouse may have eased his suffering, but his late work, it seems to me, suffered from it all. His late work might well be regarded as a casualty of war, literary PTSD. Let me make this clear, I don’t blame the swamis—they may have saved him from Seymour’s fate. I blame whatever happened to this brave and gifted man on account of Hitler. I would, wouldn’t I—I wrote a book called Explaining Hitler. But I think one cannot begin to explain Salinger, solve the enigma of the Silent Years without reference to what happened to him in sacrificing himself to defeat Hitler.

The spiritual self-medication he chose to stay alive in the aftermath may have been just enough to save his sanity. But in the end it sentenced his fiction to a fate of being bogged down in a swamp of mysticism that spelled the death of the sophisticated literary voice he had developed. (Not that sophistication is the ultimate value——but neither is didactic Seymourism.)

I’m not always one to find the solution to literary enigmas in biography—my Shakespeare book did not concern itself with who the Dark Lady of the Sonnets was. But Salinger’s late fiction—from Franny and Zooey (actually from “Zooey”—I think the dividing line comes after the almost perfect “Franny”) to Seymour: An Introduction and the almost unbearable “Hapworth 6, 1924”—begs for some biographical explanation. For the way the beautiful lucidity of his early work disintegrates into a compulsively digressive stylistic dog’s breakfast. Yes, I know Janet Malcolm, whom I revere even when I disagree with her, called “Zooey” “a masterpiece” in an essay reprinted in her new collection (though she diplomatically refrains from much of an attempt to defend the later Seymour stories). But I would ask the reader to pick up Franny and Zooey—the two stories published together in book form—and tell me “Zooey” is a masterpiece.

It is tempting to avoid this judgment of the later fiction’s apparent earnestness by giving it an ironic reading, making it cumulatively an ironic account of the damage that Eastern mysticism wrought upon Salinger’s Upper West Side Glass family, with their misguided reverence for the insufferable mystical windbag, Seymour. This is where biographical inquiry has a delicate role to play. I was trained by the Yale English department to avoid “the intentional fallacy”—seeking to discern something about a work’s meaning by reference to the writer’s usually irretrievable intention for how it should be read. But there are exceptions. Hamlet is so difficult to parse in part because we cannot know for sure Shakespeare’s attitude toward the Catholic vision of Purgatory (whence came the Ghost) since belief in Purgatory was regarded as a heresy punishable by death in the Elizabethan secret police theocracy of Protestant England at the time. So the question of whether Shakespeare harbored secret Catholic sentiments, as some have recently argued, is not irrelevant.

Nor are Salinger’s religious views. For one thing, one would like to be able to sustain a secret ironic reading against the apparent Eastern earnestness, but one would like to know what one is up against spiritually if, in fact, he was attempting to put Westerners off the wisdom of the East. Zooey in his “masterpiece” claims Seymour and his henchman-narrator brother Buddy made the younger children in the Glass family “freaks” with their incessant recitation of Bartlett’s Familiar Koans.

But if, on the other hand, it was deeply ingrained in his soul and he offered it up in earnestness and reverence to readers … blame Hitler.

In any case, having made all the caveats and excuses I could think of, I crossed the line and entered the Ramakrishna Center. (The service was open to the public.) I did it for you, dear reader. Let me say first what I did not find there. No Hare Krishna–type chanting of mantras by wide-eyed devotees. Instead a rather sedate crowd, more than half subcontinental, mostly in Western garb, looking serious. A calm disquisition on the metaphysics of transcending the self, delivered, yes, by a swami swathed in saffron robes.

As the Center’s literature puts it, “it does not deal with the occult or the sensational and offers no easy shortcuts.” There are large images of Ramakrishna and someone known as “the Holy Mother” on the front wall, but little other signs of a cult of personality.

In the end, I had to respect Salinger for his choice of a deeply serious version of the Eastern mysticism he assaults readers with in the late fiction. Maybe that was the problem. For all his disclaiming of the Mind—in the Morgan letters he warns against “mind” as if the Mind were a beast in the jungle waiting to devour the devout—he was seduced by the sheer intelligence he found herein. Because I believe, of his own sheer intelligence.

Leaving the Ramakrishna Center, I found myself thinking of another contemporary American artist and cultural icon, and finding an instructive comparison—and contrast—with Salinger’s religious conversion.

I’m thinking of the way we almost lost Bob Dylan to Jesus for three years when he became a born-again Christian in 1978. There are similarities between Dylan and Salinger: the sneering at the “phonies,” which, indeed, Dylan may have picked up from Holden Caulfield, a big influence on him, he told me in a ’78 interview; and the fabled reclusiveness—not so much anymore for the ever-touring Dylan. And then the trauma that preceded the conversion, the Hürtgen Forest for Salinger, for Dylan a shattering divorce from his “mystical wife,” as he once sang of her.

But unlike Salinger, Dylan came out of it. After a three-year period of writing songs that self-righteously preached and scolded the infidels, he gradually let Jesus go. Not without loss, however. Whatever you think of his post-Jesus work—and there’s a schism over it, the way there is over late Salinger—he lost much of the impact he had on the culture, something he ruefully acknowledges in one of his best late songs. I’m speaking of “Mississippi,” a song that he seemed to want to draw attention to by including no less than three versions of it on his recent Tell Tale Signs official bootleg. Perhaps because in it he sings, “You can always come back, but you can’t come back all the way.”

Dylan came back, at least part of the way. Some say more. J.D. Salinger didn’t come back at all, not as far as we know.

This is why I’m urging the Salinger estate and his literary representatives to end their silence. Prove me wrong. Remind us of why we cared. Tell us there’s coherent Salinger to come, and when and how. You are doing irreparable harm to his legacy—and perhaps to American literary culture—by denying us any information. Or if you can’t, if he’s forbidden you to speak, tell us it’s his wishes, not just your marketing ploy. Because after a while that’s what it’s going to look like.

So sad. I miss the guy.

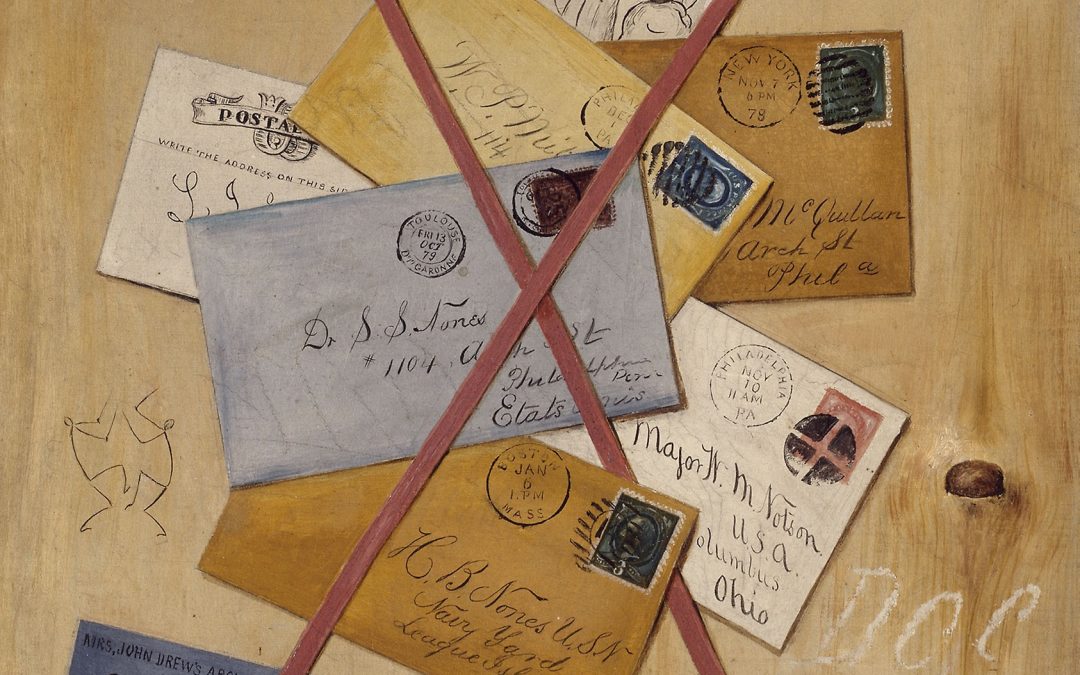

[Featured Image: William A. Mitchell via The Art Institute of Chicago]