Bill Zehme, who chronicled the lives of show business personalities in the ’80s and ’90s, died last weekend after a ten-year battle with cancer. He was 64 and one of the most personable and likable people you’d ever want to meet. Since his death, there have been a bunch of lovely tributes: The Chicago Tribune; The Chicago Sun-Times; The New York Times; The Washington Post; and Vanity Fair. Josh Karp’s 2002 profile for New City is also a must, as is this hilarious remembrance by David Handelman. I also contributed an appreciation over at Esquire.

It’s a funny thing—when a magazine journalist dies you rarely see quotes of admiration coming from his subjects. His editors, colleagues, readers, sure, maybe. But not the subjects. But in Zehme’s case, many of the people he encountered simply liked him. “Bill was a great writer and unfailingly nice,” David Letterman told VF. “But he was also emblematic of that era when profile writers were often cooler than the people they were profiling. Whenever he interviewed me, I tried inhumanly hard to impress the guy.”

Here then, are some memories of Zehme from those that new him:

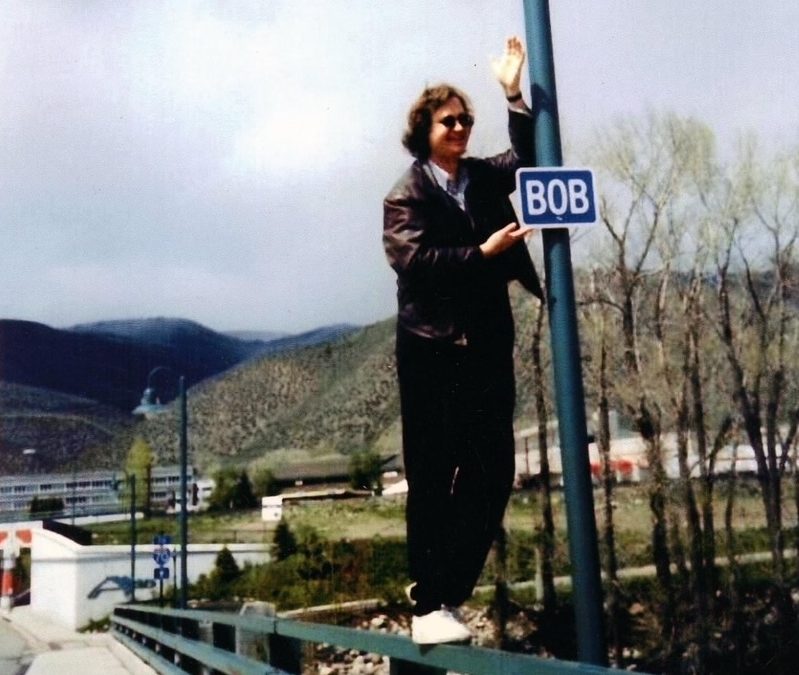

Bob Wallace (editor, Rolling Stone):

He would bring that self-effacing Midwestern sensibility that was such a stark contrast to all the New Yorkers in the office. All that modesty and self-effacement was essential in getting celebrities to open up. He just GOT IT. He was so Chicago. He would never say beer it was brewski; soda was pop; sneakers were tennis shoes. He would say, “I should probably get going.” Never, “I gotta go.”

He seemed so straight. But at heart he was an absurdist. He got comedians to take him to a place where the comedy came from. Dark place. Brighter the lights darker the shadows. He understood them. They related to him because they knew he got it. They would open up to him. He created with his gentleness and humor he bonded with his subjects. They saw him as someone with their values and roots. He had an ego, but he was always wanted to do the right thing in a conversation. He didn’t want to be overbearing.

I remember him so fondly. He seemed so straight until you sat down and talked to him. He did his thing at Rolling Stone and then moved on.

Stephen Randall (editor, Playboy):

I worked with Bill on numerous stories, interviews and 20 Questions. He was an endearing perfectionist. Good was never good enough. Things had to be perfect and while sometimes that can be frustrating, Bill had such enthusiasm and such an amazing sense of humor that you got caught up in his quest. He even brought humor to cancer, calling his treatments “keemo” to rob them of their seriousness. When I was diagnosed with a similar cancer in 2016, he became my cancer Sherpa, warning me of side effects no doctor would think to mention and telling me to listen to my body. I’ve never met anyone else like Bill.

Dave Hirshey (editor, Esquire):

There are few more wrist-gnawing moments for an editor than waiting for word from a writer in the field trying to connect with an elusive celebrity. Until that writer has nailed the interview, all you can see in your mind’s eye is a gaping hole in the magazine—and your career in tatters.

Unless I was working with Bill Zehme whose knack for tracking down and getting access to his profile subjects was never an issue. Here is how he checked in while alerting me to his whereabouts on one memorable assignment.

“Hey, Boss Man,” he said when I picked up the phone, “I’m naked with Sharon Stone.”

Though he was 6’5”, it wasn’t his height that made Bill tower over the world of celebrity journalism for some 20 years. It was his uncanny ability to radiate empathy that put his subjects at ease and gain their trust. Unlike many celebrity profilers, Bill wasn’t focused on dishing dirt or dredging the proverbial closet for skeletons. What interested him were those subtle quirks of behavior and attitude that revealed a person’s character. And he conveyed those idiosyncrasies in charmingly irreverent prose that remained distinctively his own.

Bill saw his job as “making comic hay with our cultural idols”, and only one of them failed to appreciate the playful spirit in which he wrote. That exception would be the illusionist David Copperfield, who sent the magazine a blistering three-page letter accusing Zehme of betraying his trust. In all his years of covering celebrities, many of whom had far greater cultural heft than Copperfield, this was, amazingly, Bill’s only show business feud. So excited was he to find himself at the center of his first media ruckus that Bill responded to Copperfield at equal length, encapsulating his wryly whimsical approach to his subjects.

“Just as you are known for what you do,” Bill wrote to Copperfield, “I am known—or so I’m told—for being a humorous impressionist of popular culture. My work has never been considered mean-spirited. If anything, it teases the subject, the reader, the writer, and the culture all at once.”

His work, however, did not come easily. Bill, unlike some of his peers, had never been a writer whose fingers flew effortlessly over the keyboard. He suffered for his sentences, each and every one, as he worked to capture the cadence of a subject’s voice and the essence of their personality. “So you’re the great Woody Allen?” a 1994 cover story began, “Well, he said, “I used to be.”

Bill would often take weeks, even months, before he was willing to commit his words to print. Whenever he said he was just about to file (invariably on the day the magazine was to go to press), Michael Solomon, who worked with me on his pieces, and I would hover over the fax machine, like expectant fathers outside the delivery room, and eventually exhale when we heard the whirring sound of Bill’s copy getting fed through the machine. Then we’d pull what would turn out to be a single page of three perfectly crafted paragraphs off the fax and call Bill to ask where the rest of the piece was. “Oh, it’s coming,” he’d say breezily, ” you should have it in the next couple of hours.” And sure enough, in a couple of hours, we’d hear the fax starting up again—and there it would be: another three whole paragraphs. It was the text equivalent of an IV drip. This went on for six to eight hours until we had assembled all the pages, which gave us precious little time to work them over. I’d like to tell you it was Bill’s way of keeping his editors from messing with his copy, but the truth is, after all his tinkering, Zehme’s prose was always ready for prime time.

On Bill’s reporting trips to Hollywood, he lived as large as his subjects. He’d stay at the Beverly Hills Hotel, even though the rate there was twice what his Esquire expense account allowed, and–quite bizarrely for a star magazine writer back then—Bill would pay the difference out of his own pocket. He’d tool around in a Mustang convertible and eat at all the A-list joints of the time. They included Spago and Dan Tana’s where the maitre d’s never failed to greet him warmly, possibly because he tipped them a $20 bill upon entering. Not that Bill called it “tipping”. He called it “duking” after hearing his hero Sinatra instruct a member of his entourage to “duke the guy a C-note.” Bill liked to start the night off with a dirty Stoli martini, then move on to vodka sodas, the better to wash down his signature meal of steak and baked potato. In twenty years of dining with him, I never saw a vegetable cross his lips– unless you consider a hunk of iceberg lettuce drenched in blue cheese dressing a vegetable. He would frequently fly into New York after what he euphemistically referred to as ” turning in a piece” and—with his longtime agent and wingman Chris Calhoun—the three of us would celebrate “the end of the writing ordeal” with a raucous meal at the Soho boite Raoul’s. Around midnight he’d insist on going elsewhere for a nightcap, but after one more beer I’d peel off and go home, while the other two would finish off their wee-small hour escapades with what Bill—and who knows, maybe Dean Martin before him– called a ”bonus pop.” Let’s just say that he was a man who took big gulps out of life.

Rest in peace, brother, and have a bonus pop on me.

Tom Junod (writer, GQ/Esquire/ESPN):

A few decades ago, Bill Zehme re-invented magazine profile writing. But that statement, true as it may be, implies that Bill had a raft of imitators. In truth, he was inimitable, and I know, because I tried. He was a writer who made things look easy, and as such he was like one of those rock and roll bands that made aspiring guitarists think, “I can do that,” from the refuge of their basements. He was funny without being cruel, generous without being soft, and he saw everything without resorting to judgement — he was approachable, and yet someone to aspire to. But of course, when you did aspire, in print, you found out that you could imitate all his mannerisms and still miss the music, the details he harmonized in those beautiful short sentences which accumulated on the page with cascading forward motion. And you would miss the warmth.

I know something about Bill’s warmth, because once upon a time I was its beneficiary. When I was just starting to write for GQ, I shared a panel with him and a couple of other writers on the subject of magazine profile writing. Some details I can’t remember; some I will never forget. The room was small, and packed; every editor I’d ever thought of working for was there, and to my horror the moderator asked me the first question. It was not a tricky one. But I suffered an episode of stage fright, and when I opened my mouth nothing came out. In the ensuing silence — that awful gathering silence — I heard my heartbeat, then every sound in the room, until the room began to sway, and all I could see were Ed Kosner’s shoes. Finally, I managed to blurt out the following: “I don’t know, man. I’m chokin’!” Bill saved me, by being funny without being cruel. He said, “I think what Tom is trying to say is….,” and then answered the question. But at the end of his answer, he caught my eye, and with a nod, asked if I had anything to add. I did. I took a breath, and was able to speak. I’ve been able to speak on stage ever since, and I have never forgotten what Bill did for me, and that what Bill did for me I should try to do for others.

He remains someone to aspire to, because what he accomplished in his profiles back then he also accomplished as a person. He reminded everyone who read him or knew him that we are not in the “media business”; we are in the human business, and at the heart of much great writing is a deeply human transaction that needs to be honored even as it is being recorded. We are flawed, God knows, and so is the business. But we can remain good people while doing our jobs, or at least try, and the work will be better for it. I thank Bill saving my life on stage so many years ago; I thank him for all those beautiful profiles, his inimitable arrangements of the music of personal kindness.

Mark Warren (editor, Esquire):

Since he died I have read a lot of wonderful tributes to Bill, all saying that he was a master of the celebrity profile. They are all beautiful and true, but they don’t quite do him justice. Bill was an astonishing writer, period. His voice was like no other, his control was astonishing, every sentence perfectly metered, every word sounding just right. He had his preferred milieu, to be sure – his reverence for the gods of late night bordered on the religious – but in his heart he wanted to understand people, why they did what they did, and how they got that way, their loves, their fears, their failures. And how, exactly, is that different from what all the very best writing has ever tried to do?

Richard Lewis (Friend):

Bill has written so many little pieces about me in different periodicals I have no idea what was the first. I just have this overall feeling about Bill: It’s noteworthy, clearly, to realize he was one of the most talented wordsmiths ever. Certainly, in my generation. He had an outstanding knack to get inside the head of anyone he was interviewing and get from them what nobody else could. A lot of that had to do with his genuine love of show business, his curiosity about pop culture, and how people perceive celebrities. He’d dig way deeper and get to the soul of his subjects. One that comes to mind, the extraordinary interview with Warren Beatty.

We met in Chicago most probably because Chicago became the greatest comedy city for me. Consistently. Bill wasn’t a critic. A critic that reminded me to Nat Hentoff to Lenny Bruce … Howard Reich of the Chicago Tribune became my Hentoff. Bill would be there. All sorts of Chicagoans I began to meet—after 35-40 years of performer there. Historic city for Lenny, Mort Sahl, Jonathan Winters. Important city to conquer. Bill was always on the scene. Always comes to my shows.

He wrote a book on Sinatra, and I was there so often, concerts, specials, nightclubs. The old Ambassador East, The Pump Room, they put me in Sinatra’s suite. Bill would come up. “Hey Bill, let’s walk across the top of this floor and see the entire city.” I haven’t drank in almost 30 years. Sitting there, Franks’ suite and opening a bottle of champagne, and discussing what I’m not doing. It was a dream come true to have some listen like Bill. He used to call me “the sweet prince.” We loved each other. We didn’t trash anyone. He was open to me and I was open with him. We spoke man-to-man about what was going on in our lives.

He wrote liner notes for 3 or 4 things I did but that’s beside the point.

He struggled for close to a decade. I’m so shook up by it. He was the kind of guy who made you feel like a million bucks. The last tour I did in Chicago he was very ill, but he came backstage, and we talked about the show.

I would try to reach him the next day for feedback because he was great. I was so revved up when he was in the audience I’d be flying, I could not think about not getting a rave from Bill Zehme. I would tell the owner, get Zehme back here, close to door. I want to hear straight.

Bill wasn’t a critic of mine. He was a friend who loved comedy so much. It was ingrained in his personality. He had an amazing laugh—you knew you were on the money, with a premise or a punchline when he laughed.

Or just talking in general, which I loved the most. That’s the key. I sat with him as a friend. Rolling Stone book of comedy. Liner notes for boxsets. So much time together at restaurants together, my house. It wasn’t about business it was about how much we loved the words. Words were so important to both of us. He so knew I appreciated his brain and his way of stringing words together and hooking paragraphs together and working forever to make it better. I was in awe of his ability but that was trumped by my awe of his kindness. Even after he got ill. The conversations were far and few between. When’s a good time? It became less and less. The great crazy times on Rush Street and after my shows. Doing 3 shows on a Saturday night. I’ll be done at 1:45 and we’ll go out afterwards.

I fit in to Chicago in the best possible way. “Zehme’s here, Zehme’s here,” people said when he came in a place. No other name did I hear like that. He was the kingpin.

That Laugh. I would see his eyes twinkle and then he’d laugh so loud—it was a gunshot laugh—coming back at me with love. He just loved to laugh. When all is said and done, he will be remembered for writing skills and his incredible love of comedy. He loved talking about it and seeing it. It was one of the reasons I wanted to GO to Chicago. He was that important a figure to me.

I will miss him deeply.

And now, let’s take a moment to talk about some of Bill’s work.

Cameron Crowe (from the forward of Zehme’s anthology of magazine profiles, Intimate Strangers):

He is, of course, the King of the First Sentence. And with the first sentence, you’re inside his head. Like a great tour guide, he beckons you into the inner-sanctum, whispering in your ear with a comic and sometimes poignant voice that says this is just between us. He has slopped past the personal barricades of many a generation-defining icon. And he does it by brining something new to the game—himself.

As an interviewer, and more importantly, as a writer, Bill Zehme has what the great director Billy Wilder once called the essential ingredient to anything that is memorable in life—“ a little bit of magic.”

…For decades, Warren Beatty was the great untold story in the world of movies, never to be captured . Until Zehme. And damn it, he made it look easy. He wove a tapestry out of silences… That lasting portrait is pure poetry. Never mean-spirited, always allowing the reader a front-row seat, and never returning with anything less than a real and lasting truth.

As Zehme himself would reflect on the infamous Beatty profile:

There are nights I dream of him, and it is still horrible. We are sitting there, and, of course, he says nothing. He begins to say something, and then he stops. He pauses that pause of his: The Pause! Like eternity is The Pause! I feel my hair fall out in clumps. I feel my teeth rot. At once I have aged—what?—forty, fifty years. Waiting for him to finish. To say something. But what can he say? We have both forgotten the question. He tries to respond, anyway. Blinking at me, smiling, shrugging, ageless in hesitation. There is no sound, nothing, just him, knowing what he knows and keeping it to himself. Somewhere a clock ticks as The Pause expands …

Then I awaken and remember that it was all true—it had really happened! I remember those Pauses the way other men remember mortar fire. And yet, because survival has a way of breeding nostalgia, I often fins myself missing the Reticent One.

Warren Beatty is the Reticent One. It is art, the way he withholds! To this day, I remember everything he never told me. Many people read our published conversations and summarily proclaimed Warren Beatty to be the ultimate Impossible Interview. I pity those people. Tragically, they missed everything. After all, it is not what Warren Beatty says, but how he doesn’t say it.

…Warren has seen everything and done everything, especially with actresses. More than just a fabled Lothario, he is a Movie Star in a time when there are no more Movie Stars. He is a repository of Hollywood history, an icon who knew the icons that came before him. (He played cards with Marilyn Monroe the night before she died.) His knowledge of women, all by itself, could only be encyclopedic. He would seem, then, to be a fellow who could tell you a thing or two. Someone who could bend your ear and give you something to think about.

To Warren, however, such matters are trifling. More impressive than any knowledge are his skills as a brilliant diplomat, and I would eventually learn that few things equal the sheer entertainment value of listening to a diplomat circumnavigate truth. To ensure that none of his nuance would be misrepresented in print, Warren always had a tape recorder of his own running next to mine. “It’s for your safety,” he assured me. I returned this gesture of friendship by often letting him “borrow” my extra blank tapes. Sometimes we would both run out of tape simultaneously, and those, I think, were some of our best times together.

Warren did share my concern about the seemingly futile quality of our conversations. I remember how we would pace around his swimming pool, fretting together. “Let’s keep moving around from subject to subject,” he told me, “and maybe I’ll not be boring on something.” Often I would try to engage him by sharing tidbits from my personal life. I told him how an actress had recently wreaked havoc on my heart. He asked her name, then said, by way of consolation, “I never dated her.” He then imparted staggering wisdom on the inherent perils of dating actors and actresses, but this was during an off-the-record break. I asked him to repeat himself when the tape was going, but all he said after a long silence was “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” That always struck me as one of his finest moments.

Now, about those Pauses: Never had I encountered silence to match the breadth and scope of Warren’s silences. Historically, silence, like odorlessness, is difficult to portray in print, which is understandable, since there is not a lot you can really about it. Still, I could not in good faith cheat readers out of Warren’s astonishing silences. You needed to in some way experience them to fully appreciate their richness. But how? A wise colleague at the magazine, Jeffrey Ressner, surged a solution to me shortly before I was boarding a flight to Chicago. Upon deplaning at O’Hare, I called my transcription service back in Burbank, where a team of typists was about to begin work on the interview tapes. “Time them,” I said. “Time what?” said the chief transcriber. “The Pauses,” I said. And so a roomful of women in headphones set about clicking stopwatches on and off, measuring one man’s reluctance.

Zehme did deliver some memorable opening sentences: “When your name is a punch line, you live in Hell.” (“Barry Manilow: The King of Pain” Rolling Stone, 1990); “Inside Letterman’s skull, you will find Letterman’s brain, which holds captive Letterman’s psyche, squirming, dark, and exquisite.” (“Letterman Lets His Guard Down” Esquire, 1994); “She is the kind of girl who gets you thinking that you know exactly what kind of girl she is.” (“Cameron Diaz Loves You” Esquire, 2002).

But really it’s not just the first sentence that is so good with Zehme, but the lede. Take, for instance, “The Importance of Being Arnold” (Rolling Stone, 1991):

Men are in crisis, whereas he is not. He does not know the meaning of crisis. Or perhaps he does, but he pretends otherwise. He is Austrian, after all, and some things do not translate easily between cultures. (Lederhosen, for instance.) Throughout the world, he is called Arnold, but that is because there are too many letters in Schwarzenegger. By now, everyone has come to know that the literal meaning of Schwarzenegger is “black ploughman,” and like many black poloughmen before him, Arnold knowns exactly what it feels like when a horse falls on top of him. There is much pain, yes, but pain means little to Arnold, especially when there are stuntmen available. Anyway, Arnold is never in crisis. For this reason, it is imperative that Arnold be Arnold, so that others may learn. And, from what society tells us, there has never been a more crucial epoch in history for Arnold to be alive, which is, to say the very least, pretty convenient.

And here, from one of Zehme’s personal favorites, the magnificent 1990 appreciation, “Barry Manilow: The King of Pain” (Rolling Stone):

When your name is a punch line, you live in Hell. Barry Manilow lives in Hell. There are worse hells than his. He gets to park wherever he wants, for instance. Also, he can shop recklessly and overtip in restaurants without conversation. Perdition, however, must have more dire consequences. And, as such, being Barry Manilow is no frolicsome lot. Rather, it can be an existential nightmare. Example: Sincerity is commerce. Only he never knows when to trust it. He suspects compliments. He sifts them for snide subtext. Conditioning has taught him this. Bob Dylan stopped him at a party, embraced him warmly, told me: “Don’t stop doing what you’re doing, man. We’re all inspired by you.” This actually occurred. He knew not what to make of the encounter. One year hence, it haunts him still.

Let us not forget, of course: “Warren and Me: A (Pause) Love Story” (Rolling Stone, 1990):

He is ghost. He is human ectoplasm. He is here, and then he is gone, and then you aren’t sure he was ever here to begin with. He has had sex with everyone, or at least tried. He has had sex with someone you know or someone who knows someone you know or someone you wish you knew, or at least tried. He is famous for sex, he is famous for having sex with the famous, he is famous. He makes mostly good films when he makes films, which is mostly not often. He has had sex with most of his leading ladies. He befriends all women and many politicians and whispers advice to them on the telephone in the dead of night. Or else he does not speak at all to anyone ever, excerpt to those who know him best, if anyone can really know him. He is an adamant enigma, elusive for the sake of elusiveness, which makes him desirable, although for what, no one completely understands. He is much smarter than you think but perhaps not as smart as he thinks, if only because he thinks too much about being smart. He admits to none of this. He admires to nothing much. He denies little. And so his legends grows.

I mean, goddamn. You’ll find all three of these gems in Intimate Strangers.

Dig in and enjoy. And long live one of the truly beautiful spirits.

[Photo Credit: David Rensin]