Here he is at Tiger Stadium in Detroit on a September baseball night hanging on to summer. He is getting ready to watch Jack Morris, the Tiger ace, go for win number nineteen against the Toronto Blue Jays. Elmore Leonard looks just like what a drunk mistakenly called him once in his drinking days, back at this joint called Stan’s in Fort Lauderdale: little Princeton s.o.b. Tweed jacket, high forehead, soft voice, round tortoiseshell glasses, corduroy slacks. Not anything like a tough-guy novelist who works the street the way Updike works the suburbs.

“You know who you look just like?” says an usher.

He’s stopped next to Leonard’s seat on the aisle. The usher is from the Bismarck Food Service, wearing a blue Bismarck jersey, carrying a Bismarck bucket filled with soft drinks. Name tag says MARK, IRVING. He is fifty maybe.

Leonard says, “Who?” Then he does what he does about every ten minutes, which is light up a True green and smoke it down to his wrist.

“Elmore Leonard the writer.” It is one thought to Irving Mark of Bismarck, no commas.

“Well, I am.”

“No kidding?” Mark puts down the bucket.

“No kidding.”

“I just bought your book. Glitz. The one in Atlantic City with the cop and the hooker and the crazy guy and so forth. Five bucks.”

“Well, thank you.”

“You write about Cass Corridor sometimes, don’t you?” It is a seedy downtown Detroit place, near Wayne State University. It is an Elmore Leonard place.

“Yes I do. Couple of books.”

Mark says, “I grew up in Cass Corridor.”

The stands are filling up. There are probably thirsty people somewhere behind Leonard’s seat between home plate and the first-base dugout. Irving Mark is still talking.

“No kidding. Elmore Leonard the writer. I recognized you from your picture on Glitz. They call you Dutch, right? For Dutch Leonard the old knuckleball pitcher?”

The best Elmore Leonard character might be Elmore Leonard. Now, at the age of sixty-one, he is an overnight sensation.

“I think my friends liked it better than El-more,” says Elmore “Dutch” Leonard.

“Well, I gotta go right now,” Mark says. “But let me tell you something in case I forget. You just keep doing what you’re doing and you’re going to be a very good seller. I know you’re the ‘in’ thing but don’t pay any attention to that, all right? Keep doing what you’re doing, like I said.”

Elmore Leonard, who finally got on the bestseller list with Glitz and who will be on it twice this year—Bandits now, Touch in the fall—watches Irving Mark move up the aisle. Later, he will say that he would have to write the scene from his own point of view, being floored as he was that he was recognized by an usher at the ball park. But for now he plays the scene out the way Jack Delaney would play it in Bandits or Vincent Mora in Glitz or Stick in Stick: deadpan, a little irony, cool. You have to be cool to write cool.

Leonard says, “Hey. Five bucks, and it had my picture on it. It just occurred to me he bought the book secondhand.”

The best Elmore Leonard character might be Elmore Leonard. Check it out: Twenty years ago, he’s packed it in as a full-time novelist. His big writing numbers in the early ’60s are these classics—soon to undergo the wonders of colorization—from Encyclopaedia Britannica Films: Settlement of the Mississippi Valley, Boy of Spain, Frontier Boy, and the ever-popular Julius Caesar. Thousand bucks a movie, seventeen informative minutes in length. Leonard knocks these babies off when he isn’t free-lancing ad copy for Hurst gear shifters. Hurst shifters? You bet. He says that if you had a hot rod in Detroit in 1963, you had to have a Hurst shifter or you were nowhere. Which is where Leonard was: western novelist at a time when the market was all dried up, little more than halfway through his first marriage, and an alcoholic who thought you weren’t an alcoholic unless you ended up in a skid-row gutter.

“The years 1961 to 1966 were the low point, definitely,” he says. “I had probably resigned myself to writing again sometime, but never full time.”

Now, at the age of sixty-one, Elmore Leonard is an overnight sensation.

He reads another review where somebody asks the question, “Where has Elmore Leonard been?” And says, “Where have I been? Most of the time, it’s where has he been. Like, I’ve been hiding?”

He hasn’t been hiding. Even if he had been, Leonard couldn’t hide anymore if he wanted to. It’s not just ushers at the ball park. It’s the Hollywood money men. It’s the reading public, all those people lined up at their local Waldenbooks. After LaBrava, the book before Glitz, there was a headline in The New York Times, and it was a little ahead of the game maybe, but it said it all in dry old Times-ese: WRITER DISCOVERED AFTER 23 NOVELS. LaBrava ended up selling four hundred thousand in paperback; Glitz hit the list; all of a sudden Leonard was on the cover of Newsweek.

“Sometimes,” says Joan Leonard, his wife, “the good guys win.”

The good guy is one of the big guys now. Arbor House is paying Leonard $3 million for Freaky Deaky, the one in the typewriter now, and the one after it. Of Leonard’s twenty-five novels, twenty have been sold to Hollywood. Somewhere out there, someone is having a meeting right now about some Elmore Leonard property. The sun never sets on the Dutch Empire.

Funny thing is, he’s been doing it pretty much the same way for thirty-five years, if you go back to when he sold his first western story to Argosy: “I am happy to report that your novelette, Apache Agent, is one which we like very much,” wrote an editor named John Bender. “And, by all means, let us see some more fiction.” The hard, lean writing—if he’s a boxer, he’s Tony Zale—was there from the start, in the five westerns he wrote until the middle ’60s, and then after that, when he made the move into crime fiction. Check it out: the work has been there. He’s been on the shelves. Yeah, sure, “Writer discovered.”

Dutch Leonard says, “I don’t know. It’s like there have always been a lot of Liberaces on the list—there are a lot of Liberaces on the list—and I’ve always been Herbie Hancock. No, not Herbie Hancock, people always really knew about Herbie Hancock. Where’s Marian McPartland? She doing okay? Maybe I’m Marian McPartland.”

So Leonard’s this elegant jazz man who has been working lounges all these years and suddenly somebody decides he should have been working the big rooms all along.

It all comes out of the study in the brick house on the corner of Fairfax and Pine in Birmingham, about ten miles north of Detroit. The study is a quiet and cozy room in a quiet and cozy house. Leonard has written the last eight books in this room, lived in the house since he and Joan were married in it in 1979. Why change anything? On the bookshelves across from the antique desk is a lot of ’60s research material, because Freaky Deaky is about some ’60s revolutionaries, and a scam in the ’80s, and a cop who’s getting off the bomb squad because his girlfriend is afraid he’s going to lose his hands, and…

“Over the years I’ve found out what I can do and what I can’t. I’m weak on images, for example, so I go with my strong suit. What interests me is dialogue. I compensate is what I do. You could say my style is the absence of style.”

Leonard will make it work, don’t worry. No problem. Bandits is about an ex-hotel thief named Jack Delaney who’s working for his brother-in-law at a funeral parlor, an ex-nun named Sister Lucy who worked in a leper hospital in Nicaragua, an ex-cop, a contra colonel, and $3 million that is going to move around some. It is set in New Orleans. In the study I say to Leonard, “Oh, another ex-thief, ex-nun of the lepers, contra colonel in New Orleans novel, more of that hackneyed material.”

Leonard laughs and lights up a True green. “It’s like all of them,” he says. “None of it relates until I sit down and start to write, and then it all fits together, like a what’s-his-name cube.”

Joan Leonard, a pretty blonde, pokes her head around from the kitchen. She has come in from shopping.

“Any word on LaBrava?” Al Pacino is interested in the script Leonard wrote.

“Now Pacino wants to talk to me.”

Joan says, “Cold feet?”

“I don’t know.”

Joan says, “Can he read?” and disappears back into the kitchen.

Leonard goes back to talking about his writing. This he likes to do. And he likes to read his writing aloud. Spend any time with him and he will give you a little shot of his work. The opening of Freaky Deaky. A description of Lynn Marie Faulkner’s apartment, with her Waylon Jennings poster and velour couch, from Touch. Leonard becomes an actor running lines on you, taking on attitudes and inflections, all that. He doesn’t want you to miss anything.

He says, “Listen, I know I’m different. I know my stuff has a different sound to it. But I never really thought it was big enough. I’m not plotty enough. I’m not very good at story really. I can keep them turning pages, but I’m not strong on narration. I’m always afraid I’m going to sound like I’m writing the words. So over the years I’ve found out what I can do and what I can’t. I’m weak on images, for example, so I go with my strong suit. What interests me is dialogue. I compensate is what I do. You could say my style is the absence of style.”

Who needs style when you have an ear like Dutch Leonard’s? That ear takes us to the streets of Detroit, Miami, Atlantic City, New Orleans, where grifters and con men and dreamers and the most wonderfully badass dudes any Princeton-looking s.o.b. out of the Encyclopaedia Britannica Films office ever drew are talking about some kind of score. Leonard has hung with cops, ridden in squad cars, sat in the courtrooms and precinct houses, seen busts up close. His college classmate, Bill Marshall, is a South Florida private eye. But Leonard says, “All that stuff is minor.”

I say, “Then how do you get it right?”

He says, “There’s just always been this sound that interests me. It’s the sound of savvy people, or people who think they’re savvy and talk that way. To me, they’re so much more interesting than educated people. I’m not all that interested in the way educated people think. I mean, my main characters are smart and they’ve got this attitude, you know. I don’t know. I guess I’m still a kid on the corner of Woodward Avenue listening to my friends, who were all blue-collar kids. I was an enlisted man in the Navy (World War II, Seabees). I hung around with enlisted men. I listened to enlisted men, not on purpose, just listening like you would. I spent a lot of time in my life with these sorts of people.”

Elmore Leonard was born in New Orleans in 1925 and moved to Detroit with his parents in 1934. Catholic education: University of Detroit High School. He picked up his nickname then: Dutch, after the old Washington Senators knuckleballer. He was small, 130 pounds, but he loved sports, baseball most of all. He says, “I had the desire. I read books on how to play first base. How do you do it?” When the war came, he joined the Navy, ended up in the South Pacific. Got married and joined an ad agency, Campbell-Ewald, in 1949. The marriage, which finally ended in divorce in 1977, would produce five children. The ad agency? Day job. Dutch Leonard, who had been listening real good his whole life, on Woodward Avenue and on Navy ships, was going to write. He would come out of the box writing westerns.

“A genre has a form,” he says. “That’s great when you’re starting.”

He would get up at dawn, before the kids, and make himself sit down and write a couple of paragraphs before he even put the water on for the coffee. Apache Agent was the first sale. Over the next ten years, he sold thirty stories to magazines and five western novels and even made a couple of movie sales, beginning the relationship that has evolved to where Hollywood now has got his house surrounded. The first movie—3:10 to Yuma—starred Glenn Ford and came from a 1953 story that had appeared in Dime Western. The Tall T, from a Leonard novelette, starred Randolph Scott and Richard Boone. And it was all going great until there were about six thousand westerns a week on television in the late ’50s, and nobody wanted to read about or see cowboys anymore. “I worked my ass off,” Leonard says. But by 1961, after ten years, he figured that maybe he had fired his last gun. The final novel of the first western run was Hombre.

“I don’t think any author, anybody you can name, can match his record. In a crowded field, he stands out. It took him more time than usual, of course.”

So he wrote his films and free-lanced his ad stuff and then, in 1965, he got a call from his New York literary agent, the late Marguerite Harper, who told him that the movie rights to Hombre had finally been sold for $10,000. Leonard says, “It was a lift.” It was some juice. He went back to fiction. He kept the Hurst shifters account for a while—think about the hole there’d be on the bookshelves right now if it hadn’t been for Hurst shifters—and started writing a novel. Working title, Mother, This Is Jack Ryan. It would end up being called The Big Bounce.

“We were living month to month on Hurst money, and I was writing The Big Bounce,” he says. “I considered that making my run.”

He finished The Big Bounce. Marguerite Harper took ill as she was reading it and sent the manuscript to H.N. Swanson. The legendary H.N. Swanson, the literary agent whose Hollywood clients included Hemingway and Faulkner and, Swanson’s words, “a fellow named John O’Hara, plus Fitzgerald.” Swanson, who is eighty-eight years old now and still out there working, still full of vinegar, read the book and called Dutch Leonard.

Swanson: “Did you write this book?”

Leonard: “Of course I did. My name’s on it, isn’t it ? Yeah, I wrote the book.”

Swanson: “Kiddo, I’m going to make you rich.”

Over the next three months, The Big Bounce was rejected by eighty-four publishers and film producers. Another nice Leonard twist: Bounce finally came out as a Fawcett (paperback) Gold Medal original and got sold to the movies for $50,000 and made into a dreadful movie with Ryan O’Neal and Leigh Taylor-Young.

Leonard: “Fifty thousand bucks was about what I was going to have to borrow, quick.” He was back in business. Since then, of course, he has sold everything that comes off the desk in the study in Birmingham to Hollywood.

Swanson: “I don’t think any author, anybody you can name, can match his record. In a crowded field, he stands out. It took him more time than usual, of course.”

More time than usual. You could say that. Leonard says he was always optimistic, thought he was doing okay, but that’s now. He wrote a few more paperback originals, two of them westerns, then sold The Moonshine War to Doubleday in hardcover. Hollywood would either buy, or option. Swanson, known as Swanie, was out there doing his part. But the people weren’t buying the books. The book money was nothing special.

“I learned early that if a publisher doesn’t sell your book,” Leonard says, “people aren’t going to buy your book.” If the low point for him professionally was the early and middle ’60s, the low point emotionally was the late ’60s, early ’70s. Leonard was running, but not getting any closer to daylight. He was borrowing money then—borrowing from friends, meanest sport in America—paying it back when movie or book money would come in, but not getting over having had to borrow it in the first place, because you never do.

Leonard kept turning out a book a year. And he kept drinking. A small audience knew how good he was at both.

The Saab makes its way slowly through Bloomfield Hills, the tony Detroit suburb next to Birmingham. Leonard talks about the private schools we pass and the expensive homes set back in the woods. No big deal. Little tour of the area.

I ask him where he thinks he’d be right now—writing-wise, life-wise—if he hadn’t finally stopped drinking in 1977. And Leonard says, “I’d probably be dead.” But Leonard held on, didn’t lose his job, didn’t end up in the gutter, but he was a drunk. When he drank, he got drunk. It’s just like Jack Ryan says in No. 89, he was powerless over it once he got started. By 1974, his first marriage was all but over. He had moved out of the house, into a Birmingham apartment. That was the year he went to his first meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Leonard says, “I went to my first meeting and I felt at home right away. I’m like everybody else. I did think you had to end up on skid row if you were an alcoholic. Nothing tragic had happened to me. I didn’t have blackouts. But a friend told me he thought I had a problem. Thought I should try AA. The first meeting, I admitted to myself I was an alcoholic. But it still took a while for me to accept. It took me three years to catch on to what the program is all about.” He had his last drink in January 1977.

Leonard’s first-person account of his alcoholism is in Dennis Wholey’s book The Courage to Change. He tells of being diagnosed in 1970 as having acute gastritis, and how the doctor tells him that gastritis is something you only find in “bums.” But how a month later he was drinking as much as ever. He tells about how, at the end, he began drinking before noon. It is hard to see him now as the loud, I’m-hilarious-aren’t-I? drunk he says he was, but it goes that way a lot with recovering alcoholics. They go through life hearing people say, “Not you. You never had a problem. Really?” When you are Dutch Leonard, who writes like a dream and looks like Princeton, a lot of people just don’t believe it. Recovering alcoholics, in the telling of their stories for friends, often have to act as prosecutor: Yeah, I was a drunk, and I can prove it to you beyond a shadow of a doubt.

Nine A.M., January 24, 1977, he had his last drink. Scotch and ginger ale, as he recalls. And slowly, from there, Dutch Leonard started to get to the good parts.

In the late ’70s, he left Doubleday for Arbor House, run then by Donald Fine. “He decided to sell me as me,” Leonard says. “Up until then, they kept trying to make me out to be the second coming of some dead mystery writer. Chandler, or Hammett. I barely read those guys.”

Leonard was nowhere near the best-seller list, but each book was selling a little more than the one before. The paperback money was getting fatter. Hollywood was still buying them up. And the reviews were getting better and better. John D. MacDonald, author of the Travis McGee series and another man who did his time in paperbacks, wrote that Leonard was “astonishingly good.

Maybe the best scam he ever invented was about himself, hitting it so big that he gets the movie people in Hollywood and the publishers in New York coming and going, getting them to pay now for the work he was doing all along.

In 1984 Leonard’s career just upshifted, as if he were using one of those Hurst shifters on himself. Burt Reynolds made Stick; it would end up being a shockingly bad movie (“Lots of machine guns,” Leonard says. “And scorpions. Burt couldn’t understand why I didn’t like it. He went on CBS with Phyllis George and said, ‘I thought he [Leonard] was a beautiful guy. Then he turned on me.’”). But it got some attention. LaBrava won the Edgar award in 1984; the paperback rights went for $360,000—his first big score with the publishers. The paperback rights for Glitz, after it made the list, went for $500,000. The paperback rights for Bandits were part of a cool million-dollar deal. One afternoon in the study in Birmingham, the phone rings; it is Swanson’s office. Arbor House wants to buy the next two Leonard novels for $3 million. They talk some, Leonard uh-huh’s a lot, says “if you’re comfortable, I’m comfortable,” hangs up the phone.

“I’m going to keep writing a book a year,” he says, butting out a True green. “I’ve been doing that for a long time. But I’m not going to lock myself up for that many books. I’ve been busting my butt all these years to be independent.”

I say, “Why did it finally happen to you?”

He shrugs and says, “I don’t know. If LaBrava had come after Glitz, it would’ve been LaBrava that made the list. Or if Stick was the last one, it would’ve been Stick. The popularity is unrelated to the work. Maybe it was the Edgar plus the reviews and some word of mouth, I don’t know. But all of a sudden, people were picking them up and saying, ‘Hey, this is pretty good.’”

It is a Tuesday night and the Tigers aren’t on television. When Joan Leonard puts the set on, Bruce Willis and Cybill Shepherd are yelling at each other on Moonlighting. There is a funny scene in Bandits where Jack Delaney breaks into a hotel room and gets spooked because Willis and Shepherd are screaming at each other on a television set in the next room. Leonard never uses their names, or the name of the show, but if you’ve ever seen Moonlighting, you know he is having some fun with what is supposed to be state-of-the-art TV dialogue. It’s like the umpire saying to Jim Bunning one time when Ted Williams was at the plate: “Mr. Williams will let you know when it’s a strike.” Mr. Leonard will let you know when the dialogue is right.

On the set, Bruce Willis goes into the bathroom and shuts the door. Leonard looks up from a magazine and says, “That’s the most he’s shut up in two seasons.” Gets up and turns off Moonlighting.

We have come from dinner at a restaurant called Sebastian’s in nearby Troy. Elmore and Joan Leonard have told stories about his five kids and her two, and about how they used to call her the Cookie Lady at his AA meetings (she’d show up with a plate of cookies, leave them, come back later, and pick up her future second husband).

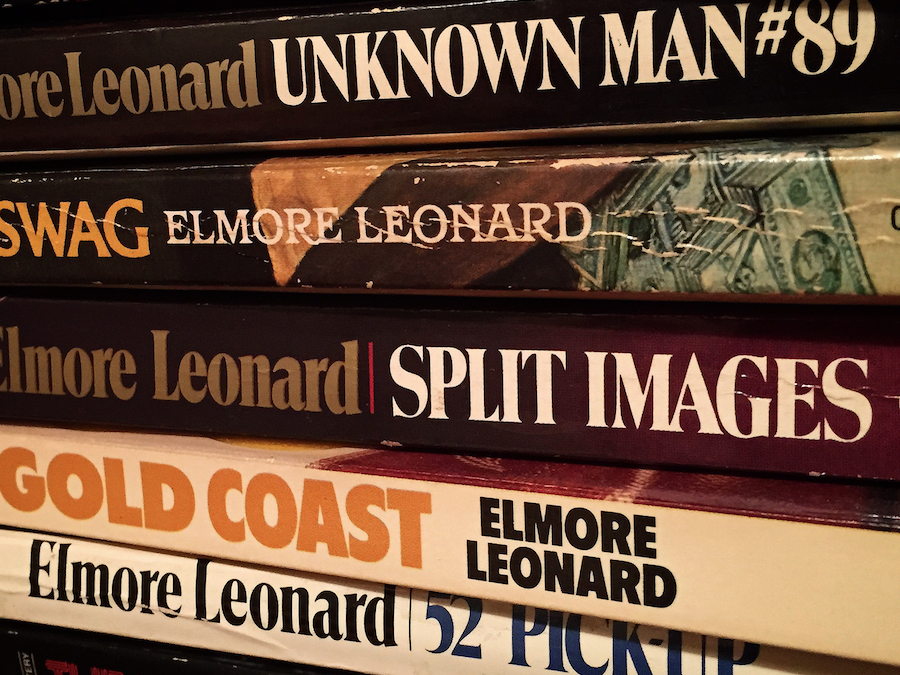

Leonard also talked about how he has never had a continuing character (true, Stick showed up in two books, Jack Ryan in two), because when Hollywood buys a book, it buys the character. Leonard laughs and tells you it’s always the same character, with a different name and a different job. Stick is an ex-con. Mr. Majestyk? Hero’s a melon picker. Vincent Mora’s a cop in Glitz. Bryan Hurd in Split Images and Raymond Cruz in City Primeval are cops. They all have been beat on by life, they all can drop a cool, wise-guy line on you, they are all tough, don’t try to push them around.

But again: maybe the best character of all is Leonard himself. Maybe the best scam he ever invented was about himself, hitting it so big that he gets the movie people in Hollywood and the publishers in New York coming and going, getting them to pay now for the work he was doing all along. The whole scam is in one book—Touch.

Leonard wrote it in 1978. It is about, his words, “mystical things happening to ordinary people.” There is a young man named Juvenal, who has been blessed with the stigmata, a condition that exhibits itself in a person’s bleeding from the same wounds Jesus Christ had on the cross, and subsequently being able to heal the sick. And there is little Lynn Marie Faulkner and a rotten talk-show host and a right-wing crazy Catholic and…

It might be Leonard’s best book. Bantam owned it for eight years. Didn’t publish it. Didn’t know what to do with it. Cut to 1985. Glitz hits the list. Leonard is the literary Lana Turner. Bantam calls and says, “We must publish Juvenal [original title].” Leonard thinks ha-ha-ha and tells Bantam that the rights have reverted to him, which they have.

Swanson says to Bantam, “You didn’t do your homework.” Offers them the book back for a ridiculously high figure. Bantam demurs. Arbor House, which is where he wanted to go anyway, buys the ten-year-old book for more than $300,000.

And now he’s sold it to the producers of Gallipoli. It’s going to be a movie.

Beat them at their own game. Dutch Leonard smiles again as he reads to you from the introduction to Touch:

“I just wanted to explain that it’s been sitting around for ten years because publishers didn’t know how to sell it, not because I didn’t know how to write it.”

[Photo Credit: AB]