Bobby Fischer heard a knock at the door. It was sometime after ten A.M., Thursday, June 29, 1972. Three days before the first game of his match with Boris Spassky for the world chess championship. Eleven hours before the plane left for Iceland. Five nights in a row, he had been booked on a northbound plane and five nights in a row he had not shown. Now time was running out. He had to take this flight. He couldn’t fly tomorrow night, because the Sabbath began at sundown on Friday and for religious reasons he couldn’t fly on the Sabbath. That left Saturday night; yet if he flew up on Saturday night, he would arrive on Sunday morning dog-tired from the trip just a few hours before the game began. So it was tonight or never. But he didn’t want to think about that right now. He wanted to rest up. He had slept 20 hours since arriving in New York about 36 hours before; but even so, he kept slipping deeper into exhaustion.

The knock was repeated. It couldn’t be the chambermaid. He had hung a DO NOT DISTURB sign on his doorknob. Who else? Only his lawyer and a few friends knew he was staying at the Yale Club.

“Package for Mr. Fischer,” a male voice called.

Looking vague and unready, Bobby opened the door and peered out, expecting to see a Yale Club employee. Instead, he saw a short, heavy-set middle-aged man in street clothes. Startled, Bobby started to close the door. The man blocked it with his foot.

“Excuse me, Mr. Fischer,” he began smartly. A younger man moved in behind him. Bobby’s eyes went wide.

“Who are you?” he asked in alarm. “What do you want?”

Keeping his foot firmly in the door, the first intruder said he was a British journalist and wanted an interview. A journalist! The match hadn’t even begun and already the press was hounding him! Bobby angrily ordered them to leave. The man with his foot in the door smiled and kept trying to wheedle an interview. Suddenly the stalemate was broken. A husky young fellow named Jackie Beers, who was visiting Bobby, strode to the door and with one strong shove sent the reporter reeling. Bobby slammed the door. Minutes later he was on the phone to one of his lawyers, Andrew Davis. “Don’t leave the room,” Davis told him firmly. “Someone will come to you as quickly as possible.” Later Davis told me: “Bobby was scared. You could hear it in his voice. At a moment when he couldn’t stand the slightest shock, he got a bad one. I guess the shock triggered it.” What the shock triggered was the wildest day in the world of chess since a Danish earl outplayed King Canute and was hacked to hamburger by His Majesty’s bullyboys.

I was 2600 miles northeast of the Yale Club when the crisis broke. I was in Reykjavik, Iceland, waiting for Bobby to fly up for the match. Spassky was waiting, too—he had arrived eight days before—and so were 140–150 newspaper, magazine and television reporters from at least 32 countries. They were getting damn tired of waiting, in fact, and the stories out of Reykjavik were reflecting their irritation.

Why was Bobby dragging his heels? Without ever talking to him, most reporters assumed that since money was the main thing he was demanding of the Icelandic Chess Federation, money was the main thing on his mind. “Greedy little punk” and “spoiled brat” began to be muttered over typewriters and the public bought what it was told. “Is it really possible,” a British correspondent asked me indignantly at breakfast Thursday morning, “that this yahoo is going to stand us all up? Either he’s the smartest little bugger that ever came out of Brooklyn or he’s some sort of nut. He devotes his whole life to chess and then turns up his nose at the world chess championship. He grows up in a slum and then walks away from millions. Does he want money or doesn’t he want money? I just can’t believe what’s happening!”

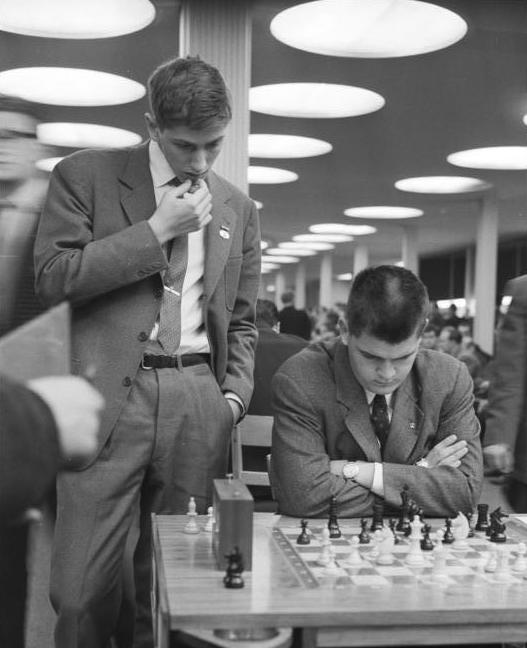

Nobody could. And nobody could believe that the most recondite of games, an intellectual sport about as popular as differential calculus, was making front-page headlines day after day; that half the world was waiting breathlessly for two young men to sit down on a solitary butt of lava in the North Atlantic and push little wooden soldiers across a miniature make-believe battlefield. The pundits explained that there was more to the match than chess. It was a war in effigy between two superpowers, the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. It was a chance to watch Russia lose the championship for the first time in 24 years and a chance to watch America win it for the first time in history. But what more than anything else had gripped us all was the downright weird personality and approximately superhuman achievements of Bobby Fischer.

There is also something primitive in Bobby’s body and the way it moves. He wears a business suit about as naturally as a python wears a necktie.

In chess circles, Bobby had been a celebrity for 15 years, ever since he won the U.S. chess championship at the incredible age of 14, but only in the past 14 months had the larger public become aware of him. In May 1971 he defeated Grandmaster Mark Taimanov of the Soviet Union, 6–0, the first shutout in more than half a century of recorded grandmaster play. He repeated the shutout against a much more dangerous opponent, Grandmaster Bent Larsen of Denmark. Then in Buenos Aires in October 1971, he gave a 6½–2½ thrashing to Russia’s Tigran Petrosian, a former world champion and, while he was at it, extended his winning streak to 21 games—the longest in chess history and one more than chess officials gave him credit for. The media decided they had better take a good close look at what they had here.

What the press had, or decided to say it had, was something known for more than a decade to his jealous rivals as “the monster”: Bobby was often discussed as a sort of paranoid monomaniac who was terrified of girls and Russian spies but worshiped money and Spiro Agnew, as a high school dropout with a genetic kink who combined the general culture of a hard-rock deejay with a genius for spatial thinking that had made him quite possibly the greatest chess player of all time. The monster was at best a caricature of Bobby, but he sure made terrific copy.

Obligingly, he made terrific copy all through the spring of 1972. First he refused to play Spassky where the Fédération Internationale des Échecs (FIDE) told him he had to play—half the match in Yugoslavia, half in Iceland. Ultimatums crackled across the Atlantic. Finally Yugoslavia withdrew, blaming Bobby’s unreliability, and the whole match was ceded to Iceland. But at that point Bobby boggled at “burying” the contest in such a tiny and “primitive” country and he complained about the financial terms, too—even though the $125,000 prize money was already ten times as high as any prize ever put up for a chess match. When the Icelanders, after a public outcry against the “arrogant Fischer,” swallowed their pride and met his demands, Bobby made new demands. When the Icelanders rejected his new demands, Bobby suddenly disappeared. Ten days before the match was scheduled to begin, nobody east of Los Angeles, not even his own lawyer, knew where he was.

On Monday, June 26, the day after he was supposed to arrive in Iceland, I called Bobby in California, hoping to cut through the contradictions and get my own impression of what he was thinking. I got a number of surprises.

“Hi, Brad! How ya doin’?” I had expected what I usually heard when Bobby picked up the phone: a faint, suspicious “Uuuuh?” that might mean hello or might be just electric clutter on the line. But this voice was startlingly rich and full and confident.

Like a kid calling home and wishing he were there, he wanted to know everything about Reykjavik. Did I like the playing hall? Was it quiet? What was the chess table like? How about the weather? “Sixty degrees! Wow! That’s coooold!” But the air was great, huh? “How about that skyr they got? Better’n yogurt, huh?”

Then he wanted to know how Spassky looked. “Nervous,” I told him, and he guffawed. “And Geller—” I began, intending to say something about Yefim Geller, Spassky’s second.

Bobby cut in fast. “Geller,” he said disgustedly, is stupid!”

Then it happened. “Geller,” we both heard a woman’s voice say, in what was obviously an Icelandic attempt to mimic Bobby’s Brooklyn accent, “is stupid!”

I heard Bobby gasp. Suddenly he went ape. “They’re listening in on my calls!” he yelled. “I knew it! They got spies on the line! Did you hear that? They got spies on the line!” His voice, so warm and vital a second before, kicked up one register and jangled like an alarm clock. Then anger came into it as the fright wore off. “That rotten little country! Call the manager, Brad! Call the head of the telephone company! I want that person found and fired!… Imagine that! Listening in on my phone calls! It could be the Russians, y’know. They got Communists in the government up there. They’ll do anything to find out what I’m thinking!” The idea amused him and he slowly relaxed.

As I put down the receiver, I thought something like this: “I’ve just been talking to two Bobbys. The happy, healthy California Bobby has decided to play. But the other Bobby, the Bobby who thinks Iceland is eavesdropping on his phone calls, could still take over and in a moment of fury destroy the match. Which Bobby are we going to get?”

Dr. Anthony Saidy is one of the more gifted and appealing members of Bobby’s coterie. He looks like a mad dentist in a comic book. His head is large, wide at the temples, curiously dished in at the back and covered with mounds of blue-black hair. His nose is an angry hook and his eyes, the color of black coffee, bulge and glitter. His credentials are impressive. He is an M.D. and a strong chess player (he once won the American Open Championship) and the author of a first-rate book on chess strategy. Yet the minute he begins to talk, he reveals himself as a diffident man, with an anxious need to please. But there is something determined and even daring about Saidy, too. In the summer of ’72, at the age of 35, he made the gutsy decision to stop practicing medicine and establish himself as a chess master and freelance writer.

Like many of Bobby’s friends, Saidy can’t quite manage to be himself in Bobby’s company. He has hitched his wagon to a star and sometimes seems afraid he might miss the ride. He seems to feel that in order to keep Bobby’s friendship he must agree with almost everything Bobby says. At times, in his anxiety to maintain the relationship, he actually encourages Bobby in his aberrations. I don’t think he means to. He is honest and loyal and his aim is always to bring his friend back to good sense and his own best interests.

Saidy is a New Yorker, but he was working for the Los Angeles Health Department when Bobby showed up in Santa Monica to stay with some friends. Saidy began visiting him every couple of days. Like most of Bobby’s California friends, he was appalled to see no move being made in the direction of Iceland as the date of the match drew near. So on Sunday, June 25, Saidy called and said casually that he would be flying East on Tuesday to see his father, who was ill. And wouldn’t Bobby maybe like to come along? “Yeah, might as well,” Bobby said vaguely. “Be nice to have company on the plane.” Saidy said he had “a strong feeling that if I hadn’t called, Bobby would still be there.”

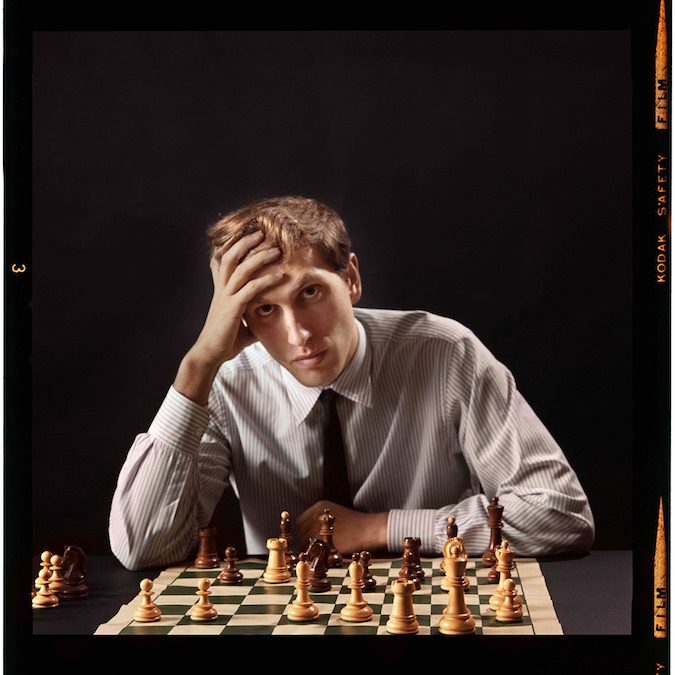

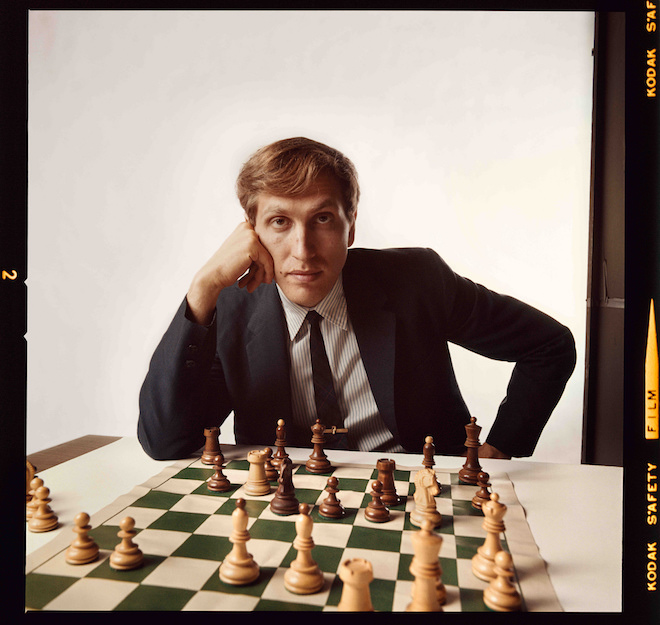

The tanned and vigorous young man who boarded the plane at Los Angeles would stand out as one of the handsome males at any gathering. Bobby is tall and broad-shouldered and his face is clean-cut, masculine, attractive. But on second glance the impression dislocates into a number of rather odd parts.

The head, for instance. That amazing brain is lodged in a smallish oval skull that doesn’t actually reach very far above the ears. The forehead is low and makes the jaw look large, at certain angles almost Neanderthal. The look on his face is primitive, too, the alert but unthinking look of an animal. A big wild animal that hunts for a living. There is a sense of danger about Bobby; in some ways I am as careful with him as I would be with a tiger. His eyes are like a tiger’s. They hold the same yellow-green serenity and frightening emptiness. And when he laughs, his wide, full-lipped mouth opens into a huge happy cave filled with bright white teeth. Most of his expressions are rudimentary: direct expressions of fear, hunger, anger, pleasure, pain, suspicion, interest—all the emotions a man or even an animal can have without being involved with any other man or animal. I have rarely seen his face register the social emotions of sympathy, invitation, acknowledgment, humor, tenderness, love.

There is also something primitive in Bobby’s body and the way it moves. He wears a business suit about as naturally as a python wears a necktie. Standing about 6’1”, he weighs close to 190, and a padded jacket makes his shoulders look so wide his head seems even smaller than it is. “Like a pea sitting on a ruler,” somebody said. His movements are direct, vigorous, sometimes comically awkward. He walks literally twice as fast as the average good hiker, but he walks the way a hen runs—and this hen fills a doorway. He comes on head forward, feet wide apart and toes turned in, shoulders lurching from side to side, elbows stuck out like wing joints and fingers flipping like feathers. Fastening his eyes on a point about four miles distant and slightly above everybody’s head, he charges unswervably toward that point through the densest crowds, a man in motion with an end in view.

New York always has a bad effect on Bobby. He goes back to it with dread and fascination, like a Jonah slipping back into his whale.

As this systematic awkwardness suggests, there are wild gaps and erratic stammers in the flow of Bobby’s life. More than almost anyone I can remember, he functions like Frankenstein’s creature, like a man made of fragments connected by wires and animated by a monstrous will. When the will collapses or the wires cross, Bobby sometimes cannot execute the simplest physical acts. When he loses interest in a line of thought or action he has pursued for as little as three minutes, his legs may simply give out, as if he had just hiked 20 miles, and he will shuffle off to bed like an old man. And once, when I asked him a question while he was eating, his control circuits got so befuddled from trying to carry two messages at once that he jabbed his fork into his cheek. Bobby has the same kind of trouble talking. He is the most singleminded man I have ever known. He seems to keep only one thought in his mind at once, and a simple thought at that. He talks as he thinks, in simple sentences that lead him where he is going like stepping-stones, and his voice is the voice of a joke robot programmed to sound like a street voice from Brooklyn: flat, monotonous, the color of asphalt.

I sometimes think it is the voice of a man pretending to be an object, so that people won’t notice he is soft and alive and then do things to hurt him. But Bobby is too vital to play dead successfully. Energy again and again short-circuits the robot. Energy like a tiger’s prowls and glares inside him. Now and then it escapes in a binge of anger. Every night, all night, it escapes into chess. When he sits at the board, a big dangerous cat slips into his skin. His chest swells, his green eyes glow, his sallowness fills with warm blood. All the life in his fragmented body flows and he looks wild and beautiful. When I see Bobby in my mind, I see him sprawled with lazy power at a chessboard, eyes half closed, listening to the imaginary rustle of moving pieces as a tiger lies and listens to the murmur of the moving reeds.

New York always has a bad effect on Bobby. He goes back to it with dread and fascination, like a Jonah slipping back into his whale. Andrew Davis knew that this time he might easily get lost inside the whale and never make it to the plane. So he had prepared the kind of script they used to write for Mission: Impossible. The plan was to abduct a man for his own good and do it so sneakily that the victim wouldn’t know what was happening to him. It was a job for a genie, but Davis didn’t happen to have one in his address book. So he asked Tony Saidy to take Bobby on a shopping trip and rounded up two friends and a professional chauffeur to help him. The friends knew Bobby but had not met Saidy. The chauffeur had never even heard of Bobby. And none of the five had ever abducted anything trickier than a cookie.

Herb Hochstetter and Morris Dubinsky, who turned up at the Yale Club at 9:30 Wednesday morning, were the first members of Davis’ crew to stand watch. Hochstetter is a stocky, energetic man of 55 with a hard business mouth and pale amused eyes almost concealed by folds of rough skin that hang down from his eyebrows like worn portieres. A man who has lived a little too hard but isn’t a damn bit sorry and would like to shoot off a few more cannon crackers before he buys a condominium in St. Petersburg. He is a well-known marketing consultant and an old friend and client of Andrew Davis, who introduced him to Bobby about 12 years ago.

Morris Dubinsky is an ex-butcher from the Bronx and as independent as a rubber chicken. When the supermarkets took over the meat business, he closed his shop and bought a taxi. Two years later, he traded it in for a $10,500 Cadillac limousine. Not long ago, he bought six limousines, all shiny new, and had enough money in the bank to pay cash—about $81,000, plus tax. “I don’t owe nobody,” Dubinsky told me. “I pay cash or I don’t get it. Payin’ cash is my biggest thrill in life. That way nobody’s gonna lean on Morris.” Dubinsky is the last man anybody would lean on. At 54, he is built (as he is the first to admit) “like an ox.” He stands 5’10”, weighs 183 pounds and has muscles in his hair. He also has muscles in his lip. When Dubinsky doesn’t like something, Dubinsky lets you hear about it—and you don’t need an ear trumpet.

By one P.M., Hochstetter and Dubinsky were getting antsy. They had called Davis several times. Davis had called Bobby and heard him mumble with a tongue like a sash weight that it was still too early. So he had urged them to sit shivah till the body resurrected. A little after one o’clock Saidy arrived and by two P.M. he had dug Bobby out. But after that almost nothing happened. Bobby lolled millionairily on Cadillac upholstery, called friends on the radiophone, picked up some traveler’s checks, had breakfast at the Stage Delicatessen, ran a couple of minor errands, and then headed back to the Yale Club for a meeting with Davis. In theory, he was getting ready to go to Iceland: in fact, he wasn’t. In everything that concerned the match, his energy was so viscous that he moved like a man struggling up out of deep sleep and knowing he wasn’t going to like what he saw when he opened his eyes.

Who could blame him? In the past 18 months, Bobby had played one long tournament and three long matches, all of them jackhammering assaults on his nervous system. Now he was facing the longest and most difficult match of his career, a contest that might run to 24 games and last up to 75 days. But Bobby had never quailed at challenges before. Something more than the challenge seemed to be troubling him now.

Andrew Davis is a slim man of middle height with quick dark eyes behind professorial specs, a small head penciled with careful hair and a big, unexpected crashing Teddy Roosevelt smile. He is 43 and has the crinkles to prove it, but he also has a squirrelly schoolboy brightness and a balloon-popping sense of fun. Davis likes to think of himself, I suspect, as something between an English master at Choate, a hard-haggling jobber in the Garment District and a dwindled Disraeli. He reads voraciously in almost all directions, but the intellectual side subordinates without overmuch regret to the zestful practical man.

At the law Davis is shrewd, precise and so ethical that friends call him Saint Andrew. He doesn’t altogether enjoy the tricks of his trade, and there are things he will not do in order to win. He shares with his father a solid unspectacular practice that provides a comfortable living but will never make him rich. He certainly won’t get rich off Bobby. People close to Bobby tell me that in 12 years as his lawyer he has never charged him a dime. Why not? “Traditional Jewish awe of intellect,” a friend of Davis’ said. “Andy sees Bobby as a sort of holy idiot, a frail vessel into which the pure logos has been poured. He will never abandon him.”

For weeks now, grating his teeth, Davis had been wishing he could. Bobby took time and energy that other clients needed. But he had hung in there because there was nobody to take his place and because he felt in his bones that Bobby was riding recklessly for a fall that might be fatal. Davis saw black if Bobby backed out of the match. The media, already annoyed and mocking, would gut him: the public, denied a spectacle it was lusting after, would remember him with disgust diminishing slowly to contempt; the chess world would write him off as a second Paul Morphy, a genius too morbid to realize his talent. Chess organizers would hesitate to sign for a major match a man who might not even show up to play.

But what worried Davis most was the potential effect of such mass rejection on Bobby himself. “Being the best chess player in the world is Bobby’s only way of relating himself to the world,” he once told me. “If he can’t function as that, he can’t function. So if he doesn’t play this match and the consequences are as bad as I’m afraid they’ll be, we could see a serious breakdown there.” Then he looked me straight in the eye and said: “Maybe suicide.”

With such risks in mind, Davis proceeded delicately when be met Bobby at the Yale Club. Bobby greeted him with a big smile, but behind the smile Davis felt wariness and resistance. So he didn’t press. When Bobby asked how negotiations with the Icelanders were going, Davis almost casually mentioned the deadlock over his demand that the players get 30 percent of the gate apiece, but he laid the blame tactfully on the Icelandic Chess Federation’s New York lawyer and suggested that a direct approach to Gudmundur Thorarinsson, the head of the l.C.F., would produce a better result. His idea was to keep Bobby pliable, to head off a hard statement of principle that Bobby would later feel obliged to stick to.

Davis respected many of Bobby’s reasons for not wanting to play in Iceland. Way back in March, Bobby had told me that Iceland was “a stupid place for the match.” He said it was too small, too isolated, too primitive. He said the hall was inadequate and he was sure that the problem of lighting a championship chess match was beyond the skills of the local technicians. As for hotels, he said there was only one on the island fit to live in, and he was convinced he would have to share it with the Russians and the press. “All the time I’d be watched. No privacy; And another thing—there’s no way for me to relax in Iceland, nothing to do between games. The TV is dull, the movies are all three years old, there’s no good restaurants hardly. Not one tennis court on the whole island, not even a bowling alley. Things like that might hurt my playing.”

Bobby was also sure that gate receipts would be disastrous because there just weren’t enough Icelanders to fill the seats—and who could afford to travel all the way to Iceland and stay there for two months to watch a chess match? But what bothered him most was the problem of coverage. A few reporters might fly in for the start and finish of the match, but the games could not be telecast to North America and Europe—no Intelsat equipment. “And this match ought to be televised. If it is, I predict that chess will become a major sport in the United States practically overnight.”

Bobby also had some financial objections. He considered himself a superstar, the strongest chess player in the world, and when it came to money, he wanted what superstars like Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali are offered. The I.C.F. had already met two of his three conditions: a guarantee of $78,125 to the winner and $46,875 to the loser and a thick slice of the film and television profits—30 percent to Boris, 30 percent to Bobby. But when Bobby demanded 30 percent of the gate, the I.C.F. had stonewalled. “If we give Bobby 30 percent, we must give Boris 30 percent,” said Thorarinsson. “But if we do that, how will we raise the prize money? No, the prize money is Bobby’s share of the gate.”

At that point, Bobby had stonewalled, too. “If I don’t get the gate,” he told Davis grimly, “I don’t go.”

Even before discussions with Thorarinsson began, Bobby had been flirting with the idea of abandoning the match. Right from the start, he had been suspicious of Iceland because it was Spassky’s first choice as a site for the match. Brooding alone in his room at Grossinger’s Hotel in the Catskills, where he had set up his “training camp,” he found enemies everywhere. He described Dr. Max Euwe, the president of FIDE, as “a tool of the Russians.” He said Ed Edmondson of the U.S. Chess Federation, the man who had spent two years of his life and about $75,000 of the USCF’s money to nurse Bobby through the challenge rounds, had “made a deal” and “betrayed” him to the Russians. By the time he left for California, he had decided that the U.S. Government was against him, too. Edmondson and Euwe, he figured, had been persuaded by Washington to sidetrack the match to Reykjavik, where a Fischer victory would be so effectively entombed that it would not disturb the developing détente between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

By the time Bobby returned to New York from California, these speculations had overgrown his mind like vines and may have obscured his view of the real situation around him. He was gripped by the idea that Thorarinsson and Euwe and the ICF and FIDE must be “punished” for their “arrogance.” He told Davis to make sure that the deal they made would prevent the Icelanders from earning a króna on the match and, if possible, would leave them with a loss. Even on those terms, he wasn’t sure he would go. He shrugged off the money he would be giving up and seemed unconcerned that the title would relapse by default to his lifelong enemies, the Russians. As for his career, he had no fears. “Everybody knows I’m the best,” he said carelessly, “so why bother to play?”

After a few minutes with Bobby, it was clear to Davis that these ideas still had the run of his client’s head. It was also clear that reasonable discourse would hardly drive them out in a day. Only a Gordian stroke could unwind his mind, and a little after six P.M., Davis delivered it.

Bobby’s eyes narrowed again. “Are you gonna make more money than me?” he demanded.

He took Bobby to the Yale Club bar for a meeting with Chester Fox and Richard Stein. Fox was the almost-unknown director the ICF had signed to make a documentary movie of the match, a 37-year-old cherub with an acute case of freckles and a halo of fuzzy orange hair. Stein was his backer, a stocky, capable wheeler-dealer who had made millions in athletic apparel and then started a second career in the law. His eyes twinkled like money and he came from a business where a man was judged by the reputation of his brand name and the size of his cigar. From what he’d heard of Bobby, he was in for some heavy haggling, and that suited him just fine.

They had come, Stein announced, to offer Bobby a deal. Bobby’s contract with the ICF guaranteed him 30 percent of all profits from the films of the match. In addition to that, Stein offered him a percentage (Fox later said that it was 12½ percent) of the profits of Chester Fox, Inc. According to Stein, all Bobby had to do in return was go to Iceland and play chess—and maybe read some comments accompanying the film Fox intended to make of the match.

Stein and Davis watched Bobby closely. For different reasons they had both hoped the offer would impress him. Instead, it seemed to confuse him and stir up his suspicions. As Stein gave a rundown on residuals, syndications, costs above and below the line, Bobby sat anxiously twisting and tearing and crushing a paper cup until he had mashed it down to the size of a lima bean. Suddenly, eyes narrow with suspicion, he broke in.

“Yeah, but how much am I gonna make?”

Stein blinked. “I realized then,” he told me later, “that deals to Bobby were like chess to me. He hadn’t understood a word I’d said.”

Patiently, Stein explained that the profits of a complicated venture are hard to predict. “But I wouldn’t be involved if I didn’t think it would make money. And whatever it makes, you get a share of that.”

Bobby’s eyes narrowed again. “Are you gonna make more money than me?” he demanded.

Stein looked helplessly at Davis. “What could I do?” he asked his wife afterward. “I was pissing in the wind. About business the guy was a shlub.”

Stein then explained to Bobby that in the American way of doing business, the people who risk the money are entitled to most of the profit. Bobby knew that, but he wasn’t sure that the principle applied when he was involved.

“Well,” Stein asked finally, “have we got a deal or haven’t we?”

Bobby wouldn’t say yes, but then, he didn’t say no. “You better hurry up,” he told Fox earnestly, “or you’ll miss that plane to Iceland.”

Davis almost cracked up. Bobby telling Fox to get on a plane to Iceland without a nailed-down deal was like Gaston at the guillotine saying, “After you, Alphonse.” But if Bobby wanted Fox in Iceland, did that mean he expected to be there, too? Had Stein’s offer made the match seem more desirable? Not for long. Ten minutes after they left, Bobby was bad-mouthing the Icelanders again. The Gordian stroke had missed its mark. Some other way would have to be found to get Bobby to the chessboard on time.

Robert Haydock Hallowell III is a big, warm, vital man who goes bounding through life like a Saint Bernard through a blizzard. One look and people know he’s loaded with the kind of hearty spirits that keep out the cold. His eyes are bright, his voice is clear, his grin is large and welcoming. He stands 6’2”, weighs 250 pounds and at 34 has the same barging energy that made him a hard-hitting third-string tackle on the worst Harvard team since World War Two. There is nothing third-string about his mind. He is a successful executive—“director of new ventures” for a producer of limited editions of medals, plates and fine-art prints called the Franklin Mint—with an education in the classics and a fine salty turn of phrase.

Hallowell met Bobby in 1966, when he supervised production for the Xerox Corporation of a book called Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess. He met Davis at the same time and became his friend and client. “I like Bobby because he fights for his beliefs,” Hallowell told me. ”I go down the line for him.”

When Hallowell showed up at the Yale Club on Thursday morning, he ran head on into a crisis. The story of The Tussle in the Doorway between Bobby and the British reporters was on the wires by 11 A.M. and in a few hours half the newsmen in New York would be camping in the Yale Club’s lobby. Bobby had to be yanked out of there fast. But that aggressive reporter and photographer were patrolling the lobby like a couple of jumpy coon dogs with a panther up a tree. Hallowell and Saidy and Hochstetter worked up a scheme to smuggle Bobby through the enemy lines.

Still indignant about the attempt to break into his room, Bobby was delighted at the idea of escape. He promised to get up soon, but three visits and almost two hours later, Hallowell and Saidy found him still stumbling around in his Jockey shorts. While Bobby washed and shaved and dressed and packed, Hallowell, Saidy and Beers sat around in the tiny room, feeling like 16 clowns in a phone booth, making small talk and helpful gestures and wondering how in Christ’s name they could ever get Bobby to the plane by 9:30 that night if this was to be the pace of progress. At last, about two P.M., the plan of escape was run off.

Saidy took the front elevator to the lobby. The reporter had left, but the photographer was still there. Principally for his benefit, Saidy informed Hochstetter and Dubinsky in a loud voice: “He’s not going out. Let’s take off.” And off they went in the limousine. But the photographer, smelling a rat, ran to check the freight entrance. He arrived just in time to see the back door swing open and Bobby, Hallowell and Beers walk out.

When Hallowell told the photographer to buzz off, he said OK and headed east on 44th Street. Bobby headed west. Suddenly reversing direction, the photographer ran ahead of Bobby and began snapping shots.

With that, Hallowell recalls, “Bobby wheeled around and took off in the opposite direction like a big-assed bird.” He turned at the corner and ran south for two blocks at top speed, dodging cars, startling pedestrians, making heads spin like turnstiles at the height of the lunchtime crush in midtown Manhattan. And after him, knees high and eyes bulging, came Hallowell and Beers. When they reached 42nd Street, they all wound down to a stop. Hallowell and Beers were gasping. Bobby had plenty of wind left. They looked back. No photographer. A big grin spread across Bobby’s face. “Really showed him, huh? Haw! Haw! Haw!”

Hallowell laughed with him. Why not? He had no way of knowing that in the incident a theme had emerged, a theme of flight that would follow their enterprise all day long like a little cold wind and before the night was over would send him racing after Bobby through rain and darkness under circumstances far more frenzied and bizarre.

The next problem to appear was Dubinsky. After one afternoon in Bobby’s company, he had decided that his chief passenger had a hernia in his head.” He was also appalled by the behavior of Bobby’s friends. “They didn’t treat him like a person. They treated him like some idiot king. I’m telling you, it was disgusting to see the way these educated people crept up his behind.”

And then came the incident at Unbelievable Syms. Dubinsky had recommended the store as a great place to buy a suit cheap (“Two hundred dollars is ninety dollars there”), but after about ten minutes, Bobby walked out. Dubinsky was suspicious. On the way to Barney’s, a clothing store on the Lower West Side, he sizzled Hallowell for dropping a cigarette ash on his precious carpet. Then he called the salesman at Syms and somehow satisfied himself that Bobby had walked out because he thought Dubinsky was getting a kickback. “And that,” as Hochstetter put it, “really started the pissing match.”

Bobby bought three expensive ready-made suits at Barney’s and then asked to be driven farther uptown to buy a Sony TV set and a digital clock. Smoldering, Dubinsky complied. Meanwhile, Bobby’s mood had also been steadily souring. On the way downtown to Unbelievable Syms, he had called Davis and warned him he still hadn’t decided to go to Iceland. Then he began telling Saidy he definitely didn’t want to go—the deals weren’t right and besides, there was too much to do first.

Saidy’s reaction was to make understanding noises that sounded dangerously like agreement. “Saidy figured it was better to ride along with Bobby on the downswings,” Hallowell told me, “and then try to carry him over the top on the upswings. But he often came off sounding mealymouthed.” Hallowell and Hochstetter reacted more aggressively. Practiced and confident persuaders, they hit Bobby with pep talks about Iceland every chance they got. Bobby in reply did little more than say “Mm.”

Everyone in the car felt a sense of rising emergency. Hochstetter cut out on a brief errand and while he was in the clear, put through a call to his brother, the film lobby’s man in Washington, and asked him to persuade Vice-President Agnew, Bobby’s favorite politician, to send a telegram wishing Bobby Godspeed. His brother tried, Hochstetter said, but Agnew couldn’t be reached.

A little while later, Hallowell got out and went to the Yale Club to pick up Bobby’s baggage and check him out. Bobby lives out of two enormous plastic suitcases that look like toasted piano crates. He had one of them in 1003, and hefting it around gave Hallowell his second unexpected workout of the day. Hochstetter joined him at the Yale Club and they both repaired by taxi to Bill’s Gay Nineties bar on East 54th Street, the point of rendezvous. At that stage, neither one had a clue if the arrow on Bobby’s compass was pointing to Iceland or to California. On the evidence available, it was possible to say only that a man who was running around town getting ready to go to Iceland was probably still considering the trip.

Bobby picked the suitcase up. The handle came off. “See?” Bobby said. Twin jets of steam, Hochstetter assures me, shot out of Dubinsky’s ears, and that was the last time that day he had kind words for anybody.

Davis turned up briefly at the Gay Nineties and carried Hallowell off to some legal meetings. A little later the limousine arrived. Bobby had his TV set but no digital clock, and after an hour without pep talks, his mood had become darker. Tuning out the conversation, he buried his head in his chess wallet.

Looking no sweeter, Dubinsky drove Bobby, Saidy and Hochstetter to a house on the Upper West Side where Bobby had left some clothes with a friend. Bobby came out carrying a suitcase with a handle that wouldn’t stay on. “And now,” said Hochstetter, “the Mack Sennett stuff started.”

Basically a sociable man, Dubinsky saw his chance to make up.

“I’ll fix it,” he said, coming forward helpfully.

“You can’t fix it,” Bobby told him irritably.

Dubinsky drew himself up. “I can fix anything!” he answered—and proceeded to. When the handle was reattached, he stood back and gestured confidently at his handiwork.

Bobby picked the suitcase up. The handle came off. “See?” Bobby said. Twin jets of steam, Hochstetter assures me, shot out of Dubinsky’s ears, and that was the last time that day he had kind words for anybody.

Shortly after 6:30 P.M., while Davis was reading over the agreement with Stein and persuading him to sign it even though Bobby might refuse, he got an anguished phone call from someone in Bobby’s party. According to Davis, the caller said: “We need you. Get here as fast as you can. Things look bad. We don’t know how long we can hold him.”

“Take him to my place right away,” Davis answered calmly. “I’ll meet you there.”

Bobby arrived at the Davis apartment looking like a grenade about to go off. “The atmosphere was so tense it was unreal,” Hallowell told me later, and Davis agreed: “It was a touchy moment. You couldn’t make eye contact with him. He was obviously at the point of refusing to take the plane. I felt like a psychiatrist trying to cool out a patient hanging on the edge.”

Instinctively, Davis played the occasion as a casual evening with old friends. His apartment is a pleasant old-fashioned straggle of fairly large rooms in a good unswanky building in the West 70s. Hallowell and Saidy and Hochstetter sank wearily into some solid nondescript chairs and a fat sofa grouped around a glass-topped coffee table. Davis’ wife, Jessie, a gentle, dark-haired woman who has made her own career as a pediatrician, brought them drinks. The three Davis children—Jennie, 14, Margot, 11, and David, 9—were in and out of the room and the conversation. Bobby took a chair in the darkest corner and sat there looking stony. But he brightened a little when he saw one of the Davis cats, a big, soft fur ball that looked consoling. Jessie brought the cat over and Bobby began to stroke it firmly and rapidly. “That cat usually likes to be petted,” Hallowell told me. “But for some reason, whenever Bobby touched it, the cat would wriggle free and run away. Jessie brought it back several times, but it still wouldn’t settle down. Finally Bobby gave up and just sat there looking peeved. He perked up again when Jessie brought him a big roast-beef sandwich and a glass of milk, but when the others tried to include him in the conversation, he just mumbled and looked away.

Davis was in his bedroom most of the time, packing and dressing for the trip to Reykjavik, but now and again he came wandering into the living room to follow the conversation and sneak a look at Bobby. Bobby didn’t seem any happier as time went by, and time went by too fast for comfort. Take-off was scheduled for 9:30 P.M. and Kennedy Airport was about an hour away. There was a second flight scheduled to leave at 9:30 that usually took off a little later and a final flight scheduled for 10:30, but Davis wanted to keep them as emergency reserves. Eight o’clock, he figured, was about as late as they could sensibly leave.

Davis checked his watch: 7:20. There was still time to call Thorarinsson and wrangle some more about the gate. As a negotiator, he knew it was the perfect moment to call. He had Thorarinsson over a barrel. With perfect sincerity he could say: No gate, no match. But as the man who had to deliver Bobby to the airport, he didn’t want to risk a refusal from Thorarinsson unless he had to. If he was reading Bobby’s mood correctly, anything less than a complete capitulation by Thorarinsson might kill the last hope of putting Bobby on the plane. So he dawdled over his packing and put off the phone call. Then promptly at 7:30, he slipped into a baggy tweed jacket, strolled into the living room and, looking at Bobby brightly, inquired: “Well, shall we go?”

It was a cool stroke and, under the circumstances, it had about as good a chance as any of succeeding, but it didn’t. The others rolled out of the chairs and moved toward the door, but Bobby looked startled and began to sputter. “Huh? What? I haven’t agreed to go! What’s the deal? What’s the deal? What about those open points?”

“Why don’t you guys go on down and wait in the car?” Davis continued calmly. “Bobby and I have some business to do.” Then he turned to Bobby. “OK, why don’t I call Thorarinsson and see what I can work out? I’ll call from the bedroom—want to come in?”

“No,” Bobby said quickly. “No, I’ll stay out here. You handle it.”

“Fine,” said Davis. But he knew the situation was anything but fine. Bobby was less interested in making a deal than in keeping his escape routes clear. As long as he stayed in the living room and let Davis handle it, he was free to repudiate any deal that Davis might make. The suicidal impulse was so obvious it was scary—scarier yet because Bobby didn’t seem to be aware of it. In order to defeat Thorarinsson, he seemed entirely willing to destroy himself.

The phone call was a disaster. “I am sorry,” Thorarinsson said coldly, “but we have gone as far as we can…. We have made concession after concession. We have done everything in our power to satisfy Mr. Fischer. But we have begun to wonder if it is possible to satisfy Mr. Fischer. We Icelanders are a generous people, Mr. Davis, but we are also a proud people. We will be freely generous, but we will not be forced to be generous.”

Davis understood Thorarinsson’s position. He was a rising young politician who at 32 was a member of Reykjavik’s city council, and his constituents were already hollering that he had given Bobby too much. Certainly he had, if by making concessions he had expected to shut Bobby up. “Even if they turned over the Bank of Iceland to Bobby,” Davis once told me, “there would still be something he wanted.” But now it wasn’t really a question of concessions. Somehow Davis had to make Thorarinsson realize, without actually telling him, that their interests at the moment almost exactly coincided, that he was just trying to find a face-saving compromise and rescue the match.

It was 7:55. Whatever he did, it had to be done in the next 95 minutes. Davis needed time to think, but the only time left was the time it took to get to the airport.

Davis walked into the living room briskly, like a man who had just accomplished something. He told Bobby curtly what had happened and suggested that Thorarinsson might take a different stand if he could be sure that this was Bobby’s last demand. “Look,” Davis concluded, “I think I can make a deal, come to some betterment based on costs. So why don’t we go to the airport now? We’ve got the limousine right here. On the way, we can talk the deal over. I can call Thorarinsson from the airport. We can keep the limousine. If we have to come back, we’ll come back. We’ll keep all our options open. OK?”

Bobby very hesitantly said OK. Davis asked Jessie to call Loftleidir (Icelandic Airlines) and tell them to hold the 9:30 plane. Jessie and the children wished Bobby good luck and then shyly kissed him goodbye. Embarrassed but pleased, Bobby hurried out to the elevator.

Outside, a light rain was falling—along with some debris from Dubinsky’s latest explosion. It seems that while waiting in the car, Hallowell and Hochstetter had realized they were hungry and had run over to Gitlitz’s Deli at 77th and Broadway. They came back with three corned-beef sandwiches—one for Saidy, too—and opened the back door of the Cadillac, figuring to get in out of the rain, where they could eat in comfort. Not a chance.

“Just one minute, gentlemen,” Dubinsky announced in the triumphant tone of a policeman who has spotted two shady-looking characters sneaking gelignite into a bank. “Not in my car you don’t eat sandwiches.”

“But Morris, it’s raining out here and we don’t have raincoats.”

“I don’t care if it’s a blizzard out there. I been through all this before. Ketchup smears on the upholstery, coffee puddles on the rug. I’m sorry, gentlemen. A car is not a restaurant. No eating in this car.”

Hochstetter, Hallowell and Saidy looked at one another, shrugged, crossed the street, sat on somebody’s steps and ate in the rain.

Damp but still game, they hurried back to the limousine when Bobby and Davis came down. Dubinsky opened the door of the limousine and waited for Bobby to get in. But he didn’t get in. He just stood there, head down and glaring, like a steer at the gate of the butcher’s van. Davis’ heart fell into his shoe. Bobby whirled at him resentfully. “I mean, what’s the deal? I still don’t know what the deal is! Why go to the airport now? There’s another plane, right? Why should I go if I don’t have a deal?”

“All right,” Davis said calmly. “Let’s walk around the block and talk about the deal.” Bobby had no raincoat on and he was carrying his chess magazines, but Davis was afraid that if they went back to the apartment to talk, he would never get Bobby out of there again. So they started off, Bobby tagging along suspiciously.

Bobby was in a foul mood, too. The minute he sat down in the back seat and felt all those big shoulders hemming him in, he began to shallow breathe and dart his eyes around like a setup being taken for a ride.

“What I have in mind,” Davis began, flashing his wickedest paw-in-the-cookie-jar grin, “is to structure a deal that gives the players everything and doesn’t give the Icelanders anything.”

Putting it like that was an inspiration. Bobby’s eyes lit up. Davis went on talking, winging it, flinging it, grabbing ideas out of the air and watching Bobby’s face as he built up a dream castle of a deal that made Bobby feel like a king and shut Thorarinsson in a financial dungeon that sounded truly dreadful but in fact had no walls at all. At one stroke Davis robbed Bobby of his main apparent motive for not going to Iceland and gave him an extra inducement to play.

“Well,” Davis wound up firmly, “shall I try it on him?” Startled, pleased, suspecting a trick but unable to see it, fighting for a delay any way he could get it, Bobby said ye-e-es. Davis got him back upstairs before he had time to change his mind. When Jessie saw Bobby walk in, her smile was something less than sincere and the cat hid.

The proposal Davis made was simple but subtle: “The players will take all the gate above $250,000.” The beauty of it was that it seemed to give Bobby plenty but actually gave him nothing. If 1500 people paid five dollars apiece to attend 20 games, the gate would amount to only $150,000—and Thorarinsson privately figured it would be less. So if he agreed to the proposal, he would merely seem to make another concession to Bobby. Thorarinsson was tempted, but he felt that the people of Iceland were so angry with Bobby that even a hollow concession might turn them against the man who made it. He also feared that Moscow might not go along. So he refused.

Davis must have done some tall talking to get Bobby out of that apartment and down to the limousine a second time. Thorarinsson had given him worse than nothing to work with, but somehow he persuaded Bobby that there was a solid chance of getting the deal he wanted before the plane took off.

The limousine pulled away from the apartment house where Davis lives no earlier than 8:45—that left about 45 minutes before take-off time. Traffic being normal, they would be about 15 minutes late. For that long, Davis was pretty sure, Loftleidir would delay the plane.

But traffic was not normal. Three minutes from home, they were caught in a jam. Dubinsky made a dog-leg and broke free—into another jam. Everywhere he turned, the East Side was a mess. It was raining harder now, too, and that didn’t help. Dubinsky’s eyes gleamed like red lights in the rearview mirror and he began to mutter.

Bobby was in a foul mood, too. The minute he sat down in the back seat and felt all those big shoulders hemming him in, he began to shallow breathe and dart his eyes around like a setup being taken for a ride. Saidy sensed the problem and force-fed him reassurance. “Man, think of the fantastic deals you’ve got! The prize money alone is ten times anything there’s ever been in chess.”

“Yeah,” Bobby said, “if I get it.”

“You’ll get it,” Saidy insisted. “It’s in trust for you. In trust means it’s there for you. And on top of that, there’s your cut of the film and television sales, the fee you’re getting from TelePrompTer for letting them use your name, not to mention the house, the car, a staff of three. And when you’re champion, they’ll be beating a path to your door with endorsements and TV and film offers. You’ll be able to write your own ticket!”

Saidy meant well, but when you’re dealing with Bobby, casting bread upon the waters often brings up a crocodile.

“Yeah, that reminds me,” Bobby said, turning to Davis, “what about that hundred and twenty-five thousand Paul Marshall said he’d get me from Chester Fox?”

Davis was startled. “What hundred and twenty-five thousand? I don’t know anything about it.”

Horror filled Bobby’s face. “You mean you OK’d the deal with Fox and it didn’t include that?”

“I don’t know anything about it.”

“Oh!” he groaned, looking almost ill with disappointment and a fury that only his respect for Davis restrained. “Ohhhhh! How could you do that?”

Another crisis. Davis began to feel like the captain of a pea pod in a hurricane. But he held steady.

“OK,” he said calmly, picking up the radiophone. “Let’s call Marshall and get the facts.” Paul Marshall is David Frost’s New York attorney, a brilliant negotiator and a specialist in international copyright law who had worked with Bobby until mid-spring, when Bobby repudiated a general agreement that Marshall had patiently teased out of the Icelanders. At that point, Marshall had resigned, but he was still friendly to Bobby’s interests in a distant, wary way.

As the phone rang, Davis noted with silent irony that the limousine was still on the Manhattan side of the 59th Street Bridge. At the present rate of progress, there was almost an hour to go before they reached Kennedy, an hour in which Bobby could dream up all sorts of mind-pretzeling problems.

Marshall sounded depressingly relaxed and unconcerned. “I thought you were already up there,” he said vaguely. “Well, what can I do for you?” Davis told him and Marshall quickly laid out the terms of an agreement he had worked out some weeks before with Fox. As it turned out, the terms were similar to the ones Davis and Stein had arrived at a few hours earlier. Marshall’s agreement was a little better for Bobby, but there was no problem, Marshall and Davis agreed. The text could be altered and Fox could sign it in Reykjavik.

“No! No! I’m not going!” Bobby announced when he heard that. “Not under those conditions!”

Davis handed him the phone.

“Look,” Marshall said. “Fox is nothing without you. He’s got to go along. What are you worried about? I make deals all day long. I know a deal when I see it. You’ve got a beautiful deal. What can I tell you? Not even Ali gets that kind of contract with a percentage guarantee.”

Bobby muttered some more, but the fire had gone out of his complaints. As often happened when Marshall began to speak, the tightness and suspicion in Bobby’s face relaxed. He let the matter drop—for the time being.

Dubinsky knew Queens like a cat knows a trash barrel, and once across the 59th Street Bridge, he struck out through back streets that hadn’t seen a Cadillac since the asphalt went down. As the car picked up speed, everybody relaxed a little and Saidy got Bobby involved in a conversation about digital clocks. Bobby said he wanted to take one to Reykjavik, and in this and other remarks, Hallowell sensed an assumption that he was going to Reykjavik that night. The mood in the limousine improved steeply. Davis began explaining his plan to elude the media people when they arrived at Loftleidir. Bobby listened eagerly—like all chess players, he dearly loves a plot. As the limousine skimmed past the first airport buildings, Davis found himself thinking that with a little luck they might just make it.

It was 9:50 P.M. when the limousine entered the traffic bay that led past the Loftleidir passenger terminal, There was a crowd in front of the terminal—passengers or press? As the limousine drifted past, Bobby sat well back in his seat. “Press up the ass,” Hallowell told me. “Looked like thirty, maybe forty newspaper and television people waiting on the sidewalk or just inside the glass doors, obviously there for Bobby.” Every third newsman wore a necklace of Nikons. Here and there, somebody had a TV camera harnessed to his shoulder. They were all jabbering and looking sharp at the cars that pulled up.

According to plan, the limousine eased to a stop about 30 yards beyond Loftleidir. Davis left the car and walked back toward the crowd. Dubinsky parked about 20 yards farther along and Hallowell doubled back to Loftleidir to let Davis know where the limousine was parked. Davis meanwhile slipped anonymously through the crowd of reporters and cameramen and was soon in close conversation with two young men.

Both were slim, alert, bright-eyed, blond. Tedd Hope stood about 6’1” and looked like Tab Hunter did ten years ago. But behind his almost-too-handsome face, there was a cool, swift executive mind. At 30, he was the manager of Loftleidir’s Kennedy operation. Hans Indridason, the other young man, was about an inch shorter and had a bright ice ax of a face. But inside the forceful image, there was a subtle diplomat. At 29, he was head of the reservations department and a trouble shooter for the president of the U.S. branch of the company. Good friends on the job and off, both of these young men were witty, honest, likable and disinclined to swallow anybody’s exhaust. Both had the punishing energy that gets things done under pressure. Indridason had been vigorously informed by his superiors that getting Bobby to Iceland was a matter of national concern, and the Loftleidir staff stood ready to move Bobby north by any means short of a viking raid on Dubinsky’s limousine.

Davis gave a quick fill-in on the situation in the limousine (“Very touchy. We’ve got to play along.”). Hope listed the remaining flights. The first of the 9:30 flights was already closed, he said, but the second was still open and there was the 10:30 flight, too.

One down, two to go.

Then the three of them put together a simple plan to elude the media and ease Bobby on board the 9:30 plane in the next ten minutes. But there were problems aside from Bobby and the press. The crowds, for one thing. It was June 29, the height of the summer rush to Europe. Cars and buses and stretch limousines, honking and gunning their engines, came whizzing into the traffic bay in front of the terminal and piled up two-deep along the curb. Then they popped open like huge parcels and out fell brightly colored passengers and luggage. People everywhere were kissing and laughing and running around with blank airport faces. A large sour-faced cop kept blowing one of those whistles that go through your head like a bright steel nail. And on top of everything, it was now raining cantaloupes.

The plan was to keep Bobby hidden in the limousine until he could be slipped into a Loftleidir station wagon and driven to the plane. “OK,” said Davis, “let’s do it.” Hope hurried off through the back of the building to get the wagon and drive it to where Bobby was. Davis, Indridason and Hallowell walked slowly back to the limousine. A few minutes later, after a rough passage through the holiday traffic, Hope arrived in a white station wagon, which he double-parked beside Dubinsky’s Cadillac. The cop promptly banged on his fender. “Move along, mister,” he said. Hope explained the baggage transfer. “Make it quick,” the officer ruled. “You see the conditions.”

Hope ran to his tailgate and opened it. Doing his duty but not liking it, Dubinsky emerged into the rain and opened his trunk. Then Hope, Hallowell, Dubinsky and a Loftleidir supervisor named Einar Asgeirsson, prodded by a cop who looked night sticks at them every few seconds, hustled Bobby’s luggage into the back of the station wagon. Davis checked the bags to make sure they were all there.

“OK,” Hope said, “it’s ten-fifteen. This plane is already forty-five minutes late. If you want to make it, we have to move now.”

“OK,” Davis said, “let’s see if we can get Bobby to go out with the baggage.”

Hallowell opened the back door of the limousine on the curb side and stuck his head in. “Bobby,” he began—and stopped. The limousine was empty.

Hallowell spun around. “Where is he?”

“I don’t know,” Hochstetter answered. “He left while you were in the airline terminal. He said he wanted to go get a digital clock, but Tony said no, he’d get it, but before he got very far, Bobby jumped out and went after him. That’s the last I saw of either of them.”

“How dare you!” Bobby burst out, whirling on Dubinsky. “How dare you take my baggage without my permission!”

Davis turned white. “Can you hold it ten minutes?” he asked Indridason, who nodded. “All right, goddamn it, let’s find him!”

Davis, Hallowell and Indridason headed off at a dead run toward the main lobby. Hochstetter waited briefly at the limousine, then decided to join the hunt.

Hope jumped into the station wagon and, in line with Davis’ instructions, drove the baggage out to the plane.

Dubinsky stared in disbelief at all this panic over one man’s momentary disappearance. Then he flung his arms in the air. “What is all this horseshit?” he inquired of nobody in particular.

Davis, Hallowell and Indridason skidded through the duty-free shops like shoplifters on roller skates. All day long, disaster had been hanging over their enterprise like a five-ton chandelier with a maniac sawing at its cable. What a rotten shame, they were thinking, to get this far and then have the roof fall in. Please, God, Davis was praying, don’t let the press find him now. The press didn’t, but another kind of trouble did. While Davis and his friends were keeping a sharp lookout for the obvious danger, they got blind-sided.

It happened like this: About two minutes after the others had left, Bobby and Saidy spotted the limousine just as Dubinsky, hard pressed by the traffic cop, was drifting it through the traffic bay to the east arcade, an area that includes a taxi stand and a secluded courtyard.

When they arrived at the limousine, Bobby asked Dubinsky to open the trunk so he could stow the clock he had just bought in one of his suitcases. Dubinsky got out of the car and explained that the suitcases were no longer in the trunk. “We moved them into an airline station wagon,” he said.

“What!, Bobby gasped, turning pale. “You moved my baggage without my permission? That’s not right!” He turned to Saidy. “That’s not right!”

Nervously, Saidy agreed—at the moment, it was difficult to do anything else. But that was all the support Bobby needed. “He was beginning to feel his power,” Davis said later. “For two days, we had all been catering to him, and now he had the airline people holding up the plane and running around doing his bidding.” All this primed his courage, and suddenly the frustration, anxiety, depression, loneliness and panic of the day came surging up and spewed out as bitter bile.

“How dare you!” Bobby burst out, whirling on Dubinsky. “How dare you take my baggage without my permission!”

Dubinsky flushed, but at first he tried to explain the situation calmly. Bobby could not listen. In a surging fury, he began to chew Dubinsky out, demanding to know by what right he had so much as touched the bags, and so on. But Dubinsky is not a man who can be chewed out.

Stocky, muscular, half a head shorter than Bobby but probably half again as strong, he came on like a wrestler, with his arms swinging dangerously and his chin thrust forward. “Listen, mister,” he announced in a voice warm with promises of strangulation, “you better keep your mouth shut. If you don’t, I’ll shut it for you, and if you don’t think I can do it, keep talking!”

Bobby went pale, but he stood toe to toe. Saidy was in a panic—if Dubinsky hit Bobby, he might knock him all the way back to California. “And I’ll tell you something else,” Dubinsky went on. “You may be a genius at chess, but in everything else you’re a big jerk!”

Bobby’s fury began to collapse. He had pictured himself as the boss raising hell with an employee, but suddenly the boot was on the other foot. “Aaaaaa!” he said, pulling in his horns and edging toward the safety of the Cadillac.

“Me,” Dubinsky yelled after him triumphantly. “I’m a genius at everything and when I do something, I do it right. What I did with your baggage I did right, and I did it on the instructions of the man who is paying me, which you are not!”

Dubinsky was still letting him have it when Bobby ducked back into the Cadillac, looking badly scared. “That man’s dangerous!” he told Saidy, rolling his eyes in alarm. “He’s violent. He ought to be put away. Who is he? He looks like some kind of foreigner.”

Saidy, who looks approximately like Abdul Abulbul Amir, replied soothingly: “Yeah, we don’t need any foreigners around here.”

Just as the fracas was ending, Davis, Hallowell and Indridason came hurrying back to the limousine from their wild-goose chase after Bobby. At the spot where the limousine had been parked, they stopped short and looked both ways along the curb. “Christ!” Davis said. Now the limousine was gone, too. Why? Where? Davis hurried over to the sour-faced cop. “Officer, if you were a smart limousine driver, where would you hide?” The cop directed them to the courtyard.

When Davis, Hallowell and Indridason arrived at the limousine, they found Bobby and Saidy sitting very quietly in the back seat and Dubinsky standing grim-faced under a canopy nearby.

“What happened?” Bobby asked in a guarded tone.

Davis said they’d all been looking for him everywhere, because the plane was already an hour late.

“Oh,” Bobby said coldly, “is there a decision from Iceland?”

Davis said no.

“So why go?” Bobby asked with a hostile stare. Davis sensed that in the past ten minutes, something had definitely gone wrong.

“Bobby,” he began carefully in the soothing, old-friend-of-the-family tone he uses so effectively with Bobby, “I think—

“I mean,” Bobby cut him off sharply, “stop trying to hustle me, right?”

It was time to back off. Bobby’s eyes were hard again. Suddenly he came to the point.

“And how about my baggage? Where’s my baggage?”

Davis looked blank, thinking vaguely of the station wagon…. It was gone! Had Hope gone ahead with the plan? Was the baggage—

Seeing Davis hesitate, Indridason leaned forward and said simply, “It’s in the plane.”

Bobby was staggered. “What? In the plane? Whaddya mean? I never said I’d go. What’s going on? I want my baggage! I’m sitting right here—I’m not getting out of this car until my baggage is returned! Do you understand? I want my baggage!”

His voice was high, his hands were trembling, his eyes were wide. It was the first time Indridason had seen him and he had the impression of “a man in a very strange state of mind.”

Davis hesitated, still hoping to turn the moment around, but Saidy jumped in to support Bobby in his headlong overreaction. “That’s terrible, that’s terrible!” Saidy said in a shocked voice, tears for some reason welling in his eyes. “You shouldn’t have done that. Putting a man’s baggage on a plane without his permission! That’s really terrible!”

That was all Bobby needed. He had found an all-purpose excuse for delay. With Saidy’s support, he rapidly propagated an awkward moment into a nightmare of shadowy motives and sinister potentials.

“That’s right!” Bobby rushed on. “How could you do that? I never said I’d go. What are you trying to do, shanghai me? Wow! They’re stealing my things! Wow! How could you do that?”

Davis and Hallowell explained that the bags had been moved with the best intentions. “In fact, we thought you were sitting in the car and watching us move them.” But Bobby refused to listen. Turning to Indridason, Davis said in tight-lipped desperation: “All right, bring the fucking bags back! Believe me,” he went on, “I know what this is doing to you. But you see what the situation is. I need time. He’s exhausted, terribly overstrained. I want to take him upstairs to a restaurant, get some food into him, try to put him in a better mood. I think I can do it. But I can’t do anything until you bring the fucking bags back.”

It was Mack Sennett time again. Indridason said he would have to have Tedd Hope’s approval. So a call was put through to the gate where the plane was being loaded. Hope boggled it further, delaying a flight already an hour late, but Indridason insisted they had to “play along with this character.”

Hope had a thought. “Look, let’s save time. We’ll drive Bobby straight to the plane in his limousine. I’ll pick up a Port Authority escort and meet you at the east gate. Bobby can inspect his baggage there. Then the limousine can follow the escort across the field to the plane.”

In a few minutes the report came back that Bobby had agreed to the scheme. After complete maneuvers that used up about ten minutes, Hope, Indridason and two airport cops in a Port Authority station wagon showed up at the east gate. Where they all waited for the Cadillac. Which did not come.

Why not? Indridason was driven all the way back to the terminal, a distance of about half a mile, so he could ask if Mr. Fischer would care to drive over and inspect his bags.

“No,” Bobby said grimly. “They have to bring them to me here.”

In the Cadillac, anxious silence followed this remark. Bobby seemed to blame Davis for the baggage incident and had almost stopped speaking to him. When he had anything to say, he said it to Saidy or Hallowell. Something had to be done to soften his mood. Saidy did it. He was hungry, he said. How about Bobby? Why didn’t they go upstairs to the coffee shop and get something to eat?

“That’s right!” Bobby rushed on. “How could you do that? I never said I’d go. What are you trying to do, shanghai me? Wow! They’re stealing my things! Wow! How could you do that?”

Davis knew the restaurant was a risk. Reporters and photographers were on the prowl everywhere. But just letting Bobby sit there in the Cadillac and stew seemed a much greater risk. Food was to Bobby what air was to a fire, and it was clear he needed some reinflation. Besides, Saidy was gung-ho to talk to Bobby alone and—who could tell? A firm hand hadn’t worked. Maybe a soft voice would. “Good idea,” Davis said.

Soaked to the skin and mad as wet hens after hand-carrying Bobby’s baggage about 30 yards through an all-out deluge, Hope and Indridason arrived in the coffee shop, where Bobby and Saidy were sitting with Davis, who had just joined them in a booth near the entrance. Determined to be polite to his difficult guests, Indridason explained courteously that the bags—actually, four or five suitcases and packages—were now stacked in a corner of the main lobby of the International Arrivals Building, about 200 steps from the coffee shop, and that Bobby could inspect them any time he liked. Hope, who had more water in his pockets and more at risk in the enterprise, went straight to the heart of the matter as far as he was concerned. “The plane is now almost two hours late,” he told Davis briskly. “You or somebody will have to make up his mind right now if he is going on this plane or not.”

“Give me a couple of minutes,” Davis answered. “I just want to talk to Bobby.”

“We’ve been giving you a couple of minutes all night,” Hope said icily and left.

Five minutes later, Davis came down to look the baggage over. “Hey, it’s wet,” he said. “He’s not going to like that.”

Somebody ran off to get paper towels, but Bobby arrived before the baggage could be dried off. He went straight to the first bag he saw and picked it up. The handle came off. Davis gulped. “I’ll—uh—” he said and snatched the handle away from Bobby.

Then Bobby noticed the carton containing his new Sony television set. “It’s wet!” he gasped.

“What do you expect,” Hope answered tartly, “coming in out of the rain?”

Bobby was appalled. “You mean this has been standing in the rain? My TV set! Oh, no! What kind of a place is this? I want this baggage dried right now!”

Davis felt it all slipping away. For the first time that night, he looked in his mind for an answer and drew a blank. He found himself feebly wiping the Sony carton with the suitcase handle.

The paper towels arrived and everybody began frantically drying luggage.

Hope asked again if anybody wanted to make this plane. Bobby said coldly, “No, I gotta talk about it some more with Tony.” Hope left, glowering, and ordered the 9:30 plane to take off. It left the ramp at 11:29 P.M.

Two gone, one to go.

“OK,” Bobby announced when the bags were as dry as five hard-working high-income executives could make them, “From now on, nobody touches my bags, understand? I want this baggage in lockers. And I want the keys.”

Nobody looked at anybody. The nearest lockers were about 90 feet away. Bobby insisted on carrying most of the bags across the lobby himself. Saidy was allowed to carry a few. Then Bobby and Saidy stowed the bags in lockers. Bobby couldn’t get the keys out of the locks, but Hallowell showed him how. Finally, with a private smile that seemed to go with feelings of power and possession, Bobby pocketed all the keys. “By that time,” Hallowell told me, “Bobby was dead white, obviously exhausted, suitcases under his eyes.” Turning to Saidy, Bobby invited him back up to the restaurant. The others he instructed to wait. Then he marched off, stone-faced, and left Davis standing there like an untipped porter.

A bleak little group gathered around Davis. The desperate extremity of the situation was clear to everyone. In chess terms, Bobby was on the verge of self-mate. In the next half hour Bobby faced a decision that must crown or crush the hopes of a lifetime, and he was clearly in no mood to make such a decision rationally. To make matters worse, Davis now looked beat. He felt as if he had whipped into a hairpin turn at 90 and all at once found himself clutching a steering wheel that had simply come off in his hands. What now?

Davis and the others went up to the bar next to the coffee shop and knocked back a belt or two. Then Davis squared off, lawyer style, for another look at the problem.

The problem wasn’t money, wasn’t Thorarinsson, wasn’t even pride or principle. Davis suspected that it was fear. Bobby at best was one of the most easily frightened people Davis knew, but he had never seen him as frightened as he was today. Frightened of what? Of losing? Of winning? Of the press and the crowds? Of being jailed by the Icelanders or assassinated by the Russians? He may have been afraid of all these things, but there was something else. Some old terror was slithering around in the bottom of Bobby’s mind. What was it? Davis had no idea and there was no time to puzzle it out now. It was midnight. The 10:30 flight, the last plane to Reykjavik, was already 90 minutes late. There was no time for tact; he had to barge in there and see Bobby right this minute.

Unfortunately, somebody else had seen him first.

It was a miracle that somebody hadn’t seen him long before. By 11 P.M., shortly after the Port Authority police drove Bobby’s bags to the east gate, most of the media people had phoned in a hard report that Bobby was somewhere at Kennedy. Then they scattered to find him. For a full hour dozens of story-starved reporters, photographers and TV camera men ran a fine-meshed dragnet through that airport. Oblivious to all this, seized by his own problem, Bobby sat in the coffee shop stuffing himself with eggs and toast and talking earnestly with Saidy only a few feet off the corridor but somehow too obvious to be seen.

The conversation was going well, Saidy said later. He felt he had finally persuaded Bobby to swallow his pride and take the plane.

And then the chutney hit the propeller.

It was a 12-year-old boy who spotted Bobby. “There was this little blond kid,” Hochstetter said. “He’d been hanging around with the newspaper photographers and the TV news crews. You could tell this was the big moment of his life.”

Worried at seeing so many press people passing so close to Bobby, Hochstetter “stayed in the hallway between the bar and the coffee shop, where I could keep track of things. This kid came along and I saw him duck into the restaurant where Bobby was eating. A minute later, he came running out and went tearing down the corridor to where most of the press was waiting.

“Those guys had been waiting for Bobby in that airport all week,” Davis explained. “They looked wild. I had a feeling they’d do violence to get their story. My heart started pounding. But it was worse for Bobby.”

“So I dashed into the restaurant. Bobby and Saidy took off just like that. ‘Go into the bar!’ I told them. ‘Way at the back! They’ll never suspect!’ So they did. Well, the whole megillah came thundering up, at least twenty of them. Nikons, TV cameras, strobes. They charged into the restaurant, and then out again. And I’m standing there. ‘You looking for Bobby Fischer?’ I said. ‘He went down there!’ And I pointed to the stairway that goes down to the lobby on the ground floor. So they all ran down there and I figured that’s the end of that.”

About two minutes later, they all came charging back up again. “And then that damn kid fooled me,” Hochstetter continued. “He went snooping around in the bar and spotted Bobby again and came running out, hollering, ‘He’s in there! He’s in there!’ So then they all rushed into the bar.”

Hallowell was ready for them. When they hit the end of the bar, they ran into a 34-year-old 250-pound former third-string tackle on the worst Harvard team since World War Two and he threw the greatest block of his career. For about 30 seconds, Hallowell had 20 men piled up in front of him. “I’m sorry, gentlemen,” he announced suavely, making like the manager, “but the bar is closed.”

“I’m from NBC!” a reporter informed him importantly.

“No shit,” Hallowell answered calmly.

Suddenly they all broke through Hallowell, but as they went charging toward Bobby, they met Bobby charging out. Face closed and shoulders twisting, he pushed quickly through the startled pack. There were shouts, flashes, shoving, clutching, cries of “Bobby! Bobby!”

It was a scary moment, and not only to Bobby. “Those guys had been waiting for Bobby in that airport all week,” Davis explained. “They looked wild. I had a feeling they’d do violence to get their story. My heart started pounding. But it was worse for Bobby. There’s something about strobes, flashbulbs, strong sudden bursts of light. Maybe his eyes are more sensitive. Anyway, it seems to hurt him physically. He’ll do anything to get away from it.”

Just ahead lay the corridor. As Bobby hit it, he turned left. Hallowell was not far behind him and right behind Hallowell was a TV cameraman, an assistant carrying a battery pack and a rack of lights and the 12-year-old boy who had started it all. The lights were blazing, the camera was whining and the boy was squealing, “Mr. Fischer! Mr. Fischer!” as they all turned left, too.

At that moment, a large male hand covered the TV camera’s lens. It belonged to Hochstetter, who had been waiting in the corridor for just such an opportunity. “It was like putting pepper in a Turkish wrestler’s jockstrap,” Hochstetter told me happily. “The cameraman let out a scream. The lighting man screamed, too. Finally they pushed me out of the way, but as the cameraman went past, I gave him a good swift kick—right in the crack. He gave a yell and turned around and started after me. I backed off. I mean, I’m a devout coward. I didn’t want to fight. All I wanted was to give Bobby a chance to take off.”

Bobby got it. He ran down the stairs three and four at a time, Hallowell about 20 feet behind him. Indridason, who happened to be standing not far from the bottom of the steps, said Bobby’s eyes were wide and blank. After him, yelping with alarm, came the pack of news-hounds.

Thanks to Hochstetter’s holding action, Davis and Saidy reached the stairs ahead of the press and raced for the bottom, where they turned to make a stand. For about five seconds they body-checked the roaring horde. Somebody threw a punch at Saidy. Davis gave way slowly and as the TV cameraman rushed past him, he stepped accidentally, he insists, on the cord that connected the camera to the battery pack. The camera went dead. The cameraman stared in disbelief. First some son of a bitch had grabbed his lens and kicked him in the slats. Now this son of a bitch had unplugged his camera. It was too much. Screeching incoherently, he snatched off his glasses and with his camera still harnessed to his shoulder, pushed a floppy little punch at Davis’ head.

By the time the press broke out of the stairwell, Bobby and Hallowell were out of sight.