Don Bolles wanted to be the best reporter in Arizona. That was all he wanted. It had always been enough for him. By all accounts he was an old-fashioned man, steeped in such Calvinist beliefs as industry, thrift, and piety. He would not have had much in common with what are known in Arizona as “eastern slickers.” Above all, Bolles was a shrewd reporter, a writer of cautionary tales—tales to which few of his readers paid much attention. Alive, he was engaging, but taciturn, difficult to know. Dead, he is the sort of man of whom others now say, “Oh, he wasn’t like that at all, you know.” Suffice it to say that Don Bolles lived for little more than his work and his family. He did not die satisfactorily.

Bolles had been an investigative reporter for fourteen years and the term always amused him, particularly after it had come into fashion, since it seemed to him redundant. He prided himself on his accuracy. It was a quality on which he placed the highest value. Since going to work for the Arizona Republic in 1962, Bolles had rapidly become the state’s leading journalist.

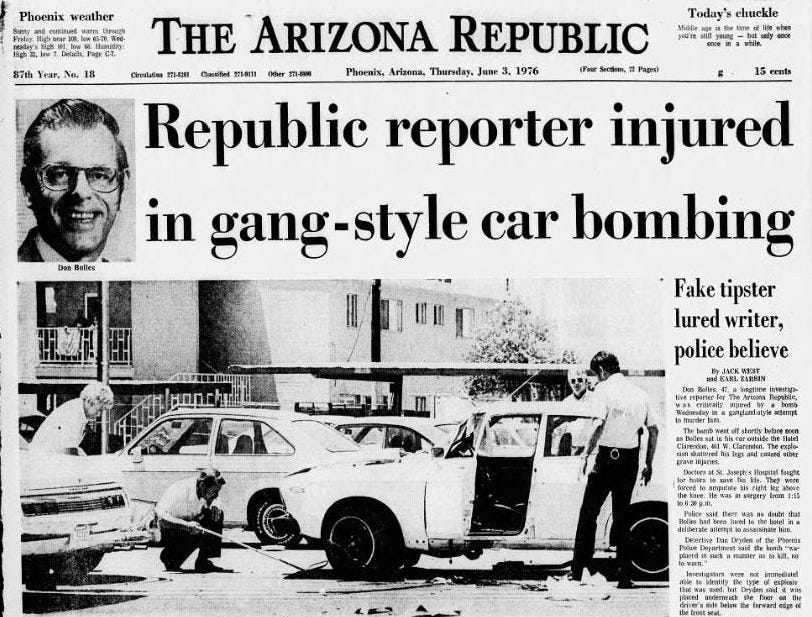

The Arizona Republic is published by Nina Pulliam, the widow of Eugene C. Pulliam, who purchased the paper in 1946. It has a daily circulation of 235,000. A conservative paper, the Republic has many of the hallmarks of provincial journalism. Its front page carries “Today’s Chuckle” and “Today’s Prayer.” In the lobby of the Republic-Gazette building in downtown Phoenix, there is a bronze plaque that quotes Eugene Pulliam. It says: IF YOU FORGET EVERYTHING ELSE I’VE SAID, REMEMBER THIS—AMERICA IS GEAT ONLY BECAUSE AMERICA IS FREE. Arizona is a state in which such words are still capable of stirring occasional passions.

Over the years, Don Bolles wrote hundreds of stories attacking the erosion of those freedoms in the “Valley of the Sun.” In 1965, he was nominated for the Pulitzer prize for his investigations of bribery and other irregularities in the state tax and corporation commissions. In 1967 a Bolles series was the Republic’s first major effort to expose land fraud in Arizona. During the late sixties and early seventies he wrote extensive pieces on Emprise Corporation, the Buffalo-based firm that, along with the Funk family of Arizona, controlled the state’s dog tracks. In 1974 Bolles received the Arizona Press Club award for a series exposing a conflict-of-interest scandal in the Arizona Legislature. He was perhaps best known for revealing the infiltration of Mafia figures into Arizona in a series entitled “The Menace Within.”

Don Bolles had always wanted to be a newspaperman. The son of an Associated Press reporter, he was born in Milwaukee in 1928. He attended high school in New Jersey and graduated from Beloit College in Wisconsin in 1950. Following a stint with the army in Korea, he worked for nine years as a sports editor and rewrite man for the Associated Press. At the Republic, rarely a week went by when Bolles and such colleagues as Al Sitter, Bernie Wynn, and Paul Dean did not attack the spreading network of crime and corruption that had mushroomed in Arizona since the war. But toward the end of 1975, Bolles began to lose his taste for battle. Because of his articles, his life had been threatened many times. In fact, the lives of all the Republic’s leading reporters were threatened repeatedly. Paul Dean once received a piece of chemically impregnated paper that said, “Put this under water and see what will happen to you.” When Dean put it under a faucet, the paper burst into flame. Bolles’s wife, Rosalie, often pleaded with him to take their name from the Phoenix telephone directory and Bolles had always said, “No, people have to be able to get hold of me.” Only late last year did Bolles finally accede to her request.

In the months before he died, Bolles had taken to referring to a policy of “official gutlessness in town.” He told his colleague Bernie Wynn that “no one out there cares.” He had grown tired of threats. He had grown tired of public apathy and official incompetence. He had grown tired. Late last year, he asked Bernie Wynn if he could rejoin Wynn’s capitol bureau and report on the Legislature. And when asked if he intended to continue his investigative reporting at some future date, Bolles replied. “No, no more of that. Nothing ever happens.”

Investigative reporting has been glamorized recently. There’s nothing glamorous about it. It’s little more than patient drudgery.

Bob Early, the Republic’s city editor, is very proud of his paper’s investigative work, particularly in the areas of consumer fraud and governmental corruption. A tough editor, he has been known to tell young reporters, “Kid, I want you to go out and talk to that guy and come back with an objective story that’ll hang the son of a bitch.”

Early sympathized with Bolles’s frustrations. “I’ve seen the same thing happen to many reporters in many places. After about ten years of investigative work it gets to you and you need a break. Don worked all the time, including weekends. Investigative reporting has been glamorized recently. There’s nothing glamorous about it. It’s little more than patient drudgery. You get untold harassment from lawyers, a lot of nasty rumors spring up around you, and you get enormous pressure from your family. Add to that the frustration of nothing ever happening and all of a sudden you want to lead a normal life.”

Thus, when the Arizona State Senate reconvened last January, Don Bolles occupied himself with reporting on the capitol and Democratic politics. Beyond his journalism, he devoted himself to church work, to occasional tennis and daily jogging, and to his family. Bolles and his wife had seven children—four from his previous marriage, two from hers, and a six-year-old daughter, Diane, who had been born deaf. At the age of 47, Bolles had wearied of kicking against the pricks, of battling an intractable system, but in the back of his mind he thought he would write a book about Arizona one day—a state, in his view, which promised everything and, for the most part, failed to deliver.

On Thursday morning, May 27, Don Bolles received a telephone call from a man who claimed to have information concerning a land-fraud deal involving Senator Barry Goldwater, Congressman Sam Steiger, and former GOP state chairman Harry Rosenzweig. Bolles was suspicious but agreed to meet the man. He returned to the Senate press room later in the day and told Bernie Wynn that he had met “a sleazy bastard … from San Diego” who had had nothing concrete, but who had promised information and documentation at a subsequent meeting.

“That didn’t mean that Don had changed his mind about investigative reporting,” said Wynn. “He had no intention of doing the story himself. He was going to pass it on to the city desk.”

Over the Memorial Day weekend, Bolles spent his time with his family. They remained for the most part at home, though on Monday they visited the Pulliam-owned Lazy R & G Ranch, where they swam and had lunch.

On Tuesday morning, June 1, the informant phoned again and Bolles arranged to meet him the next day. The following morning Bolles left the house around nine o’clock, as he usually did. He was wearing a new blue leisure suit and his favorite white shoes. June 2 was his eighth wedding anniversary, and before he left the house Rosalie had given him a new billfold. They planned to go out for dinner that evening and afterward to a showing of All the President’s Men. Bolles did not mention his meeting to Rosalie, saying only that he was going to a lunch at Sigma Delta Chi, and, because it was the babysitter’s day off, he would pick up their daughter from school that afternoon.

Getting into the white four-door 1976 Datsun he had bought less than a month before, Bolles drove to the state capitol to attend a meeting of the Senate. The meeting broke up just before eleven. Bolles went down to the press room, made a few calls, and just after eleven he departed, leaving a note in Bernie Wynn’s typewriter which said: “I’ve gone to meet that guy with the information on Steiger at the Clarendon House. Then to Sigma Delta Chi. Back about 1:30 p.m. Bolles.” He then drove to the Clarendon House Hotel in downtown Phoenix. When obtaining tips of this kind, Bolles always chose public places—hotels or restaurants. He was not a man to take unnecessary chances and had at one time taped the hood of his car with Scotch tape so that he could tell if it had been tampered with.

The Clarendon House on West Clarendon is a smallish, modern hotel that manages to give an air of age and dilapidation. Bolles parked his car in the parking lot to the rear of the hotel. His appointment was for 11:15, and the tall, bespectacled reporter, his fair hair pushed back into a loose pompadour, walked into the hotel punctually. He looked round the tiny lobby and out through the glass doors to the pool beyond, but there was no one there. Judy Holliday, the front-desk clerk, asked if she could help and Bolles said he was looking for someone and would wait on the sofa. Some five minutes later the telephone rang. Miss Holliday answered it, frowned, then, looking at the seated journalist, asked if he was Mr. Bolles. Bolles nodded and the girl switched the call to the house phone. Later, Judy Holliday remembered only snatches of the conversation. She remembered Bolles said something about the capitol, that he had told the male caller to go to the Senate Office Building, or something like that, that Bolles had talked for about two minutes before hanging up. Bolles thanked the girl and left. The appointment, presumably, had been postponed.

Squeezing between his Datsun and a battered purple Volkswagen, Bolles got into his car. Reversing a few yards, he cocked the front wheels slightly to the right in order to leave the parking lot. It was then that the explosion occurred. The blast ripped the car’s four hubcaps off, blew out the windshield, and cut a two-foot hole in the floor beneath the driver’s seat. Windows in nearby cars were blown out, and a huge cloud of white smoke billowed up from the shattered Datsun. The explosion blew open the door on the driver’s side and Don Bolles flopped out onto the pavement.

The first person to arrive on the scene was Lonnie Reed, a young refrigeration technician who had been installing an air conditioner nearby. Lying face down on the parking lot, Bolles looked up and said, “Help me, help me.” Reed took the belt from his Levi’s and, using it as a tourniquet, tied it around Bolles’s right thigh. Two minutes after the blast, Fire Captain John Albright arrived. A small crowd had already gathered, some of whom had attempted to alleviate Bolles’s pain by putting loose dressings on his wounds and tying a belt around his other thigh. He was semiconscious. “His legs were all shattered,” said Albright. “The right leg, the kneecap, had been blown off, and part of the calf, and the same on the left. He was … trying to get up.” But Bolles could not move. Lifting up his head, his glasses gone, his face blackened from the blast, Bolles asked that his wife be telephoned and said that he was a reporter. He then muttered: “They finally got me—the Mafia, Emprise. Find John Adamson.” Those were the last words he said.

The news of the explosion was relayed via police radio to the city desk of the Arizona Republic. The report said that an unnamed reporter had been driving a cream-colored foreign car. Reporters began gathering round the city desk. At first, city editor Early thought the reporter was Al Sitter. Over the years, Sitter had written several stories a week attacking fraudulent land deals and the men behind them. Sitter had been threatened countless times and he drove a cream-colored foreign car.

A few minutes later, Sitter walked into the newsroom. “When I arrived,” he said, “everyone was gathered around the city desk and Early looked up at me and said, ‘You’re not dead?’ I was astonished. I used to drive a white Toyota, but my wife drives it now.” The reporters were relieved, but a few minutes later the telephone rang. Early answered it, listened for a moment, then put his hand over his face. “Jesus Christ,” he said, “Jesus Christ.” Then he told the reporters that the victim was Bolles. The stunned reporters stood round the city desk in silence. “What the hell was he working on?” shouted Early. None of the reporters knew.

Don Bolles was removed from the hotel parking lot to nearby St. Joseph’s Hospital, where, in five hours of surgery, the doctors amputated his right leg above the knee. Following the operation, Bolles remained conscious though in critical condition. Later that afternoon, when Bernie Wynn began to sift through the papers on Don Bolles’s desk, he found a note. It said: “John Adamson. Lobby at 11:15. Clarendon House. 4th and Clarendon.” He gave it to the police.

The following morning the Arizona Republic and the Phoenix Gazette offered a reward of $25,000 for information leading to a solution to the bombing. At the hospital, Bolles was conscious though unable to speak. Two police officers showed him a photograph of John Adamson and by nodding his head Bolles confirmed that he was the “sleazy bastard from San Diego.” Again, by nodding, Bolles confirmed that it was Adamson who had made the call to the Clarendon. The 32-year-old Adamson was arrested the next day on an old charge of defrauding an innkeeper. He arrived at police headquarters with his lawyer. A squat and brutish man, he wore dark prescription glasses, a white suit, and white shoes. He looked like the bouncer in a second-rate bar. He listed his profession as self-employed greyhound owner. He was photographed, fingerprinted, said nothing, and was released on $100 bail.

Oddly, the police did not have him tailed, an opportunity Bob Early did not overlook. As Adamson strolled from the county jail, nearly ten reporters and photographers lay in wait for him. They made little attempt at surreptitious shadowing. Rather, using three cars they followed him openly. Adamson soon wearied of their pursuit. Careening through light traffic and parking lots, he attempted to elude them. After a 30-minute chase, two of the reporters’ cars nearly collided, and Adamson disappeared. But he was soon tracked down to his favorite haunt, the Ivanhoe Cocktail Lounge. He spent the rest of the afternoon and early evening there, making and receiving telephone calls and sending his shoes out to be shined. He left only once—to have a manicure next door.

John Harvey Adamson is a minor figure in the Phoenix underworld. He had been a model student at Phoenix’s North High School, the president of the school’s Latin club, and a mainstay of the school band, in which he played trombone. His subsequent career had been obscure. In 1973 he owned a tow-truck operation. The business entailed chaining cars to cement slabs in assorted Phoenix restaurant parking lots and extracting sizable sums to have the chains removed. He was also wanted on at least two charges of defrauding innkeepers, but little more was known of him.

On the afternoon of June 4, Don Bolles received 32 pints of blood. Four days later, in order to obviate the risk of further infection, doctors amputated his right arm between the elbow and the shoulder. Bolles had lapsed into unconsciousness and his condition was now described as very grave.

Later in the day Neal Roberts, a Phoenix attorney, told the police that Adamson had been with him fifteen minutes before the explosion and could not possibly have had anything to do with it. Neal Roberts was to become a central figure in the case. Six feet five inches tall and graying, the 45-year-old Roberts is not merely suave; he seems almost afflicted with a slick western panache. He claimed to have met Adamson some two years before in the Ivanhoe Cocktail Lounge in that part of downtown Phoenix known as the central corridor. “John raises greyhounds,” said Roberts. “I raise springer spaniels, so we started spending some time together.” Roberts has a reputation of being one of the best civil attorneys in Phoenix, though how he acquired the reputation is obscure since he is rarely seen in the local courts. An expert cardplayer, he is often to be found in the prestigious Arizona Club playing gin and pitch.

Neal Roberts told the police that Adamson had been in his offices, a five-minute drive from the Clarendon House Hotel, with another man, a certain Henry Landry, who turned out to be a one-legged convict and professional gambler. Roberts remembered the occasion well because his secretary’s watch had stopped and she had telephoned the operator for the time. It had been 11:18. He and Landry, Roberts explained, had driven to the airport in order to send a greyhound to a distant track. Adamson had gone his own way and had seemed in no particular hurry. Police later learned that the airport receipt had logged the dog in at 11:10, which meant that Roberts would have had to have left for the airport at about 10:45. Roberts insisted there had been a clerical error. Roberts described Adamson as “a Damon Runyon character,” though when questioned by police he called him “the friendly neighborhood assassin.” Despite Roberts’s alibi, Adamson was arrested again, this time for not paying a bill of $136 at the Clarendon House Hotel in 1975. Again, he said nothing and was released on bail.

“With the assassination of Don Bolles, the City of Phoenix realizes it has come of age. The slimy hand of the gangster and the pitiless atrocities of the terrorist are part of the current Phoenix scene.”

On June 5, the police searched Adamson’s apartment and discovered magnets, firecrackers, electrical wire, tape, and a booklet entitled The Anarchist’s Cookbook published by a radical group. The booklet gave detailed instructions on how to manufacture bombs. On the afternoon of June 10, doctors at St. Joseph’s Hospital amputated Don Bolles’s left leg. Bolles had now developed pneumonia and his temperature had risen to 104 degrees.

Sunday morning, June 13, he finally died. Two hours later, John Harvey Adamson was arrested in the Ivanhoe Cocktail Lounge and charged with murder. Three days later the lead editorial in the Arizona Republic proclaimed: “With the assassination of Don Bolles, the City of Phoenix realizes it has come of age. The slimy hand of the gangster and the pitiless atrocities of the terrorist are part of the current Phoenix scene.”

Days later, after the funeral, after the tributes had poured in from across the nation, days later, after the initial shock, for most, had passed, Rosalie Bolles, the reporter’s widow, sat quietly in the living room of her Phoenix home. In the next room three plain-clothes detectives watched television. Diane, the Bolleses’ pretty six-year-old daughter, skipped into the room, speaking in a high incomprehensible stutter—a stutter her mother seemed to understand perfectly. “She was … Don’s favorite,” said Mrs. Bolles. She started to say something else, then stopped and turned away.

“Don always said the Mafia had too much money to think of killing,” she said. “They had their lawyers and the courts. They didn’t have to resort to gangland tactics in Arizona. I don’t know. Even Don’s … uh … adversaries respected him,” she said in a low voice.

Again, she looked away. “I don’t know what will come of all this,” she said. There was no bitterness in her voice, only regret and resignation. “I’m afraid Don made me something of a cynic, too. I would hate to think that nothing good will come of his death. It’s hard enough coping with the fact that your husband was murdered without thinking it was all in vain.”

On June 21, a preliminary hearing was held in the Maricopa County Superior Court to determine whether John Harvey Adamson should be brought to trial. Security was strict. Adamson sat sullenly in a front row, his heavy arms folded across his white Maricopa County jail T-shirt. He wore, as he always did, dark glasses. He now sported a light mustache. He was pleading not guilty.

One of the first witnesses called to the stand was Robert Lettiere. An ex-convict, Lettiere said he owned 30 greyhounds in partnership with Adamson. He admitted he had been convicted of grand larceny and burglary in Minnesota some years before.

The world inhabited by Lettiere, Adamson, and their friends was described by the prosecution as a mean and shabby one—replete with gambling and dodgy business dealings. Adamson himself was described as an unemotional braggart, a man who talked of hitting it big, a tough guy who probably saw himself as the major heavy in a minor film. His world seemed to revolve around a series of bars and cocktail lounges on and around North Central Avenue in downtown Phoenix—Durant’s, the Phone Booth, Navarre’s, La Strada, Smuggler’s Inn, and the Ivanhoe Cocktail Lounge. In the old days, Adamson had operated his tow-truck scam in the parking lots of many of these bars, but it was in the Ivanhoe that most of the characters who were to surface in the case seemed to have spent their idle hours.

The Ivanhoe is in a little complex off North Central Avenue—a mock-English pub that should have been mock-Scot. The walls are decorated with phony coats of arms, a picture, a sword or two. Its main attraction seems to be the portable phone that Adamson spent much of his time using. From lunchtime onward, the bar is populated with what appear to be unemployed cowpunchers. Many of them affect straw hats, jeans or slacks, natty short-sleeved shirts, and oddly, because the room is very dark, dark glasses. There is a rash of turquoise jewelry, sideburns, and toothpicks. It is the epitome of Sun Belt chic. The low seats which run along the wall opposite the bar are tended by waitresses. The waitresses are good old girls, girls who like to jive with the boys, but who giggle and register faint distaste when lewd male suggestions are made by saying, “Dahlin, you’re real disgustin’.” It’s an eerie underworld, the Ivanhoe. The Muzak plays “The White Cliffs of Dover,” the street cowboys comfort themselves with toothpicks and the telephone, and the waitresses giggle with approximate charm. In the pecking order of the cocktail lounge, Adamson held a high position. He and Robert Lettiere did much of their drinking here.

On Friday, May 28, five days before the bombing, Lettiere said, he and Adamson had driven to the Arizona Republic parking lot to look for Don Bolles’s car. En route, “Adamson mentioned he had a job to do. He said he was going to blow up a car and the reason he was going to the parking lot was the car would be there.” He was going to blow up Bolles’s car because “some people don’t like this guy.”

The two men did not find Bolles’s car, however. As they left the parking lot, Adamson had said, “Well, I couldn’t do anything here anyway.” The two men then drove to a Datsun dealership lot where Adamson checked beneath the hood and inspected the undercarriage of a new Datsun. During their drive that day, Adamson asked Lettiere if he would be willing to help him “by following the guy around” to determine his habits. For that, Adamson promised Lettiere 10 percent. He said he was getting ten grand for the job, but he had also been offered another job at $25,000. Lettiere declined. “It’s not my bag,” he said. Lettiere said he hadn’t seen Adamson over the Memorial Day weekend, but that he had spoken to him by telephone at the Ivanhoe at 11:15 the morning of the bombing. They had actually met just after noon at the Ivanhoe. Lettiere told Adamson that a bomb had exploded over on Clarendon, and Adamson had said, “Yeah, I know.”

The night of the bombing, Lettiere telephoned Adamson at Neal Roberts’s home. Shortly afterward, as arranged by Roberts, Adamson and his wife were flown by chartered plane to Lake Havasu in the northern part of the state. But Adamson returned unexpectedly to Phoenix the next day. “His people,” said Lettiere, “called up and told him to get back in a hurry.” That day. June 3, Lettiere and Adamson sat outside Lettiere’s home and Adamson said that “he expected his money in a day or two and was glad to know his people were behind him.” Adamson regretted only one thing. “That was a hell of a charge I built under that car,” he said. “I can’t understand how the man lived. If I ever get another foreign car to do, I’ll make damn sure it isn’t a Datsun.”

On June 5, Robert Lettiere was married and John Adamson was his best man. There was a small wedding celebration at Lettiere’s house. The state’s other star witness was Mrs. Gail Lynn Owens, a former girl friend of Adamson’s. Thirty years old, with auburn hair falling to her shoulders, she wore a simple striped-cotton dress. Her features were pale and parched; she looked like a waitress on her day off. For the past twelve days she had been guarded by detectives, moving between three cities in two states. Mrs. Owens was the daughter of a wealthy California packing-company owner.

On the stand she explained she had spent nine days with Adamson, between April 20 and April 29, at the King’s Inn motel in San Diego. While there, they had gone to West Coast Hobbies and Games, where Adamson said he wanted to buy a gift for a friend. Mrs. Owens said she did not know what the gift was, but back in the motel she opened the box and looked at it. It was a remote-control device, she said. Adamson told her he was going to make a lot of money, and if that job went well, he would have two more. On June 2, after the bombing, Adamson telephoned her and said: “Something’s happened and I won’t see you for a while.” Mrs. Owens said she did not ask why.

Lettiere and Owens were the prosecution’s two main witnesses. Adamson had registered momentary surprise when they were called to the stand; but more often than not, he sat impassively in his seat and yawned occasionally. When the thirteen-hour hearing ended, Adamson was ordered to stand trial for murder; the trial is set for October 1. Adamson was removed to the Maricopa County jail.

Excluding Alaska and Hawaii, Arizona is the youngest of the American states, having achieved statehood in 1912. State politics and Phoenix businesses are still influenced or controlled by members of old families who were born here when it was known as the Arizona Territories. Phoenix, its capital, was a cow town in 1950, and its metropolitan area, with only 106,000 people then, now has a population of 1,355,000. It is the fastest-growing city in America. According to Arizona novelist Edward Abbey, “Arizona is the native haunt of the scorpion, the solpugid, the sidewinder, the tarantula, the vampire bat, the cone-nosed kissing bug, the vinegaroon, the centipede, and three species of poisonous lizard: namely, the Gila monster, the land speculator, and the real-estate broker.” It is an area steeped in the lore of Cochise and Geronimo, Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, and the gunfight at the O.K. Corral. Today, Arizonans are fond of referring to their state as the urbanized frontier. And there is a quality of ruthlessness still surviving among these people, something quite inexorable, a reflection of the landscape in which they live, the desert that encompasses them.

“Phoenix may look big,” I was told, “but don’t let it fool you. Phoenix is a very small town.” It is the sort of town where girls still marry in their teens, where it is said the only good Indian is a dead Indian, where men still speak of shoot-outs and rangeland justice, and where cars sport slogans such as Praise John Birch and Praise the Lord. The New West reminds one of the Old.

Arizona is rich and there is in the state an exaggerated reverence for money. Predictably, then, in the wake of the population boom, crime has followed fast afoot. According to Phoenix police, there are more than 200 members or associates of the Mafia living in the state. Many of them have acquired holdings in local restaurants, bars, and hotels. Their operations include ownership or partial ownership of loansharking syndicates, grocery-store chains, and the bribing of local government officials. Tucson, only 60 miles from the Mexican border, may now be the country’s chief drug-distribution center. Arizona is also known as the land-fraud state—a state in which local “white-collar criminals” have bilked the American public of more than $500 million in the last ten years. In Arizona, crime is commonplace.

According to Al Sitter of the Arizona Republic, “Arizona is supposed to be the new frontier, the land of rugged individualism. I don’t know whether it’s the desert, the climate, or what … but there’s a kind of craziness here.” Don Bolles spent fourteen years of his life writing about that craziness. Before he died, he mentioned three names—the Mafia, Emprise, and John Adamson. He knew his enemies well and those names he didn’t trust to memory he kept in carefully documented files. “He was a meticulous man,” Paul Dean recalls. “The name that popped into his head popped into his files. You could write entire stories based on Don’s notes. You’ve only got to look; it’s all there.”

There were known Mafia members in Arizona before the war, but the first major family head to arrive was Joseph “Joe Bananas” Bonanno in 1943. Moving from New York to Tucson, he bought a home and invested in, among other things, land, a parking lot, and an Italian bakery. He claimed he had come to Arizona to retire. By 1968 Bonanno and his wife held some $329,823 in Pima County real estate. His personal wealth is estimated at about $1 billion.

“Bonanno is not in retirement,” said a Phoenix police officer. “Don’t you believe it. The only time a Mafioso retires is when he dies. He’s operating, but quietly. I believe Bonanno has just taken over operations for the Mafia on the West Coast, and that means Denver to San Jose to L.A. to Tucson.”

Another heavy investor in Arizona real estate is Peter Licavoli. Licavoli, the former head of Detroit’s “Purple Gang,” has served two sentences—one for eighteen months for smuggling liquor from Canada to the United States and another for income-tax evasion. On his release in 1960 from an Atlanta jail, Licavoli told a reporter: “I’ve made more money in legitimate business deals in Arizona than I ever made from bootlegging.”

Along with eastern Mafia infiltration into Arizona came eastern-style gang-land murders. In 1955 William Nelson, a law-abiding citizen, had lived in Phoenix for seven years. He looked about as conspicuous as a retired tailor. He was much-respected. He knew Harry Rosenzweig, the former GOP state chairman, and was often to be found in Rosenzweig’s jewelry shop. Nelson’s real name was William “Fat Willie” Bioff. He was an ex-convict and labor racketeer who had earned parole from a shakedown sentence by testifying against five members of the old Capone gang twelve years before. He also testified at a movie extortion trial in 1943 against Sidney Korshak, a high-priced labor lawyer with close connections to organized crime.

Bioff was probably the first criminal to have taken refuge under the federal “alias” program, and for a time in Phoenix most people knew him as Willie Nelson. Harry Rosenzweig knew better. In 1952 he persuaded a reporter not to reveal Nelson’s real identity on the ground that Nelson was now an honest citizen. Bioff stopped into Rosenzweig’s jewelry store and offered to repay him. Rosenzweig told him to forget it. Bioff insisted. Finally, Rosenzweig said, “Bill, just give me the money you would spend on a present and I’ll put it to good use.” Bioff gave him an envelope. It contained $5,000 and Rosenzweig put it into the Goldwater Senate campaign fund.

According to Ed Reid and Ovid Demaris in The Green Felt Jungle, Fat Willie Bioff knew Barry Goldwater well. At one time he ferried Bioff in his private plane to parties all over the Southwest. In October of 1955, the senator and Mrs. Goldwater flew Mr. and Mrs. Bioff back to Phoenix from Las Vegas in Goldwater’s private plane. At first Goldwater denied that he knew Bioff, then said he had only known him under his alias, and finally, that he had associated with Bioff in order to learn the inside story of labor racketeering.

On November 4, 1955, Bioff turned on the starter of his new Ford pickup truck and ignited six sticks of dynamite. Pieces of the truck struck homes a block away. Fat Willie Bioff was hurled 25 feet onto his front lawn. The blast ripped off both his legs and his right hand. His murder was never solved.

In December of 1958, Gus Greenbaum, gambler, bootlegger, close friend of Bugsy Siegel’s, and former owner of the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas, was found dead in his Phoenix home. So was his wife, Bess. Their throats had been slashed with a nine-inch butcher knife. Among the mourners at their funeral was Senator Barry Goldwater. Their murders were never solved.

Only last October, Joseph Nardi of Phoenix got into his ten-day-old 1976 Lincoln Continental Mark IV. As he backed out of the parking lot, a plastic explosive placed near the rear axle was ignited, shattering 75 windows in his apartment complex and obliterating Nardi. “Nardi,” of course, was an alias. He was, in fact, Louis “the Bomber” Bombacino, a former Mafia legman, thief, and government witness. Bombacino was the ninth known gangland victim in Arizona since 1955. All of the murders remain unsolved.

Don Bolles wrote at length on the activities of Emprise Corporation in Arizona. Emprise is the $100-million conglomerate run by the Jacobs family of Buffalo, which controls at least 162 different corporate entities. It is said to have had long and intricate financial transactions with such Mafia heads as Moe Dalitz of Las Vegas, Anthony Zerilli of Detroit, and Raymond Patriarca of Providence. In 1972, Emprise was convicted of conspiring to conceal ownership of the Frontier Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. As a result, and after a complex exchange of stocks, Emprise is now a subsidiary of Sportsystems Corporation. Another newly created subsidiary, Ramcorp Metals, Inc., along with the Funk family of Arizona, controls all of Arizona’s dog tracks and one horse track in Prescott.

Despite the conviction and despite the fact that Bolles hectored Emprise for seven years, nothing was done before he died. Only afterward did the Arizona Legislature finally pass a watered-down piece of legislation requiring the Funk family and Ramcorp Metals to divest themselves of two of the six dog tracks they owned. But the divestiture provision was not to take effect until the end of 1978. Thus the illegal monopoly that Bolles had urged be broken would remain intact for at least two and a half years after his death.

Al Sitter is the Republic’s resident expert on land fraud, but it was Don Bolles’s 1967 series that marked the paper’s first major effort to expose the phenomenon. Land development is big business in Arizona, and more than 2,000 land companies have sprung up in the last decade.

Dr. James Johnson, an assistant professor of sociology at Arizona State University, has been investigating land frauds for nearly two years. “All you need is a lawyer, an accountant, a businessman, and a politician to pull off a successfully fraudulent scheme,” he said. “Land fraud works as follows. The promoters get hold of a piece of desert, which they don’t even own except on paper, though they have an authorization to sell. They grossly inflate its value, misrepresent the hell out of the land, claim it will be ultra-developed, and then palm it off with high-pressure salesmanship to cold, urban Northerners for only 5 percent down. That’s easy, but the big money comes when you then sell the mortgage to anybody you can get to buy, to suckers, either individuals or banks, at a 20 percent discount or even higher. Sometimes you use the buyer’s promissory notes as collateral in order to get inflated loans at the bank. Invariably, you milk the money out of the corporation and disappear before the company goes into bankruptcy. In that way, everybody’s screwed, except the promoters, of course, and all that’s left is what was there to begin with—the desert.”

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Arizona land sales exploded. The man behind many of the state’s largest land companies was Ned “the Godfather” Warren. Despite Bolles’s nine-year investigation of Warren, the Godfather remains luxuriously at large.

Ned Warren was born Nathan J. Waxman in 1914 in Boston, the son of a prominent Jewish family. He attended the Lawrence School in Brookline and graduated from Worcester Academy in 1931. He attended the University of Pennsylvania briefly. He began his career in advertising, and in 1941 changed his name legally to Warren. From the beginning, Waxman-Warren practiced the complicated art of the confidence man: The only thing that changed was the stakes. Between 1946 and 1949 he was charged with numerous cons—convicted of conspiracy in Chicago and placed on two years’ probation, charged with fraud in Denver and grand theft in San Francisco. In 1949 he was dispatched to Sing Sing for two to six years for collecting $39,000 from numerous New York angels for a Broadway show called The Happiest Days, which never opened. Warren was out in a year.

“Just because two people sue each other doesn’t mean they aren’t in business together.”

In the mid-fifties, Warren moved to Florida, where, operating with the firms of Zun Industries and the Dixieland Development Company, he attempted to sell land—Everglades swampland—by mail. He was stopped by the Florida Real Estate Commission. In 1958, he was arrested by the FBI on a charge of concealing $25,000 in assets from a personal bankruptcy. As a result, in 1959–60 he resided in the Danbury, Connecticut, Federal Correctional Institution. In October of 1961, now on parole, Ned Warren moved to Phoenix. He claimed to have reformed. “My record in Arizona is impeccable,” he liked to say.

In 1965 Warren moved to Western Growth Capital as a salesman for its owner, Lee Ackerman, a former Democratic national committeeman, state legislator, and onetime unsuccessful candidate for governor. In February of 1967, about fourteen months after Warren sold his interests in Western Growth, the company was forced into bankruptcy. Ackerman sued Warren for $40 million. When the books were examined, court officers said the company finances had been undercut by questionable sales practices. But no action was taken.

“Just because two people sue each other doesn’t mean they aren’t in business together,” said Detective Lonzo McCracken of the Phoenix Police Department. The 42-year-old McCracken had been one of Don Bolles’s best friends. “In my experience, when that happens, I always look for the real victim,” he said. “I always look for the guy they’re really screwing.” In this case the victims were not difficult to find. When Western Growth went bankrupt, thousands of innocent people lost their investments. They have never been compensated. No one went to jail.

The Phoenix police have been trying for years to prosecute those men behind land fraud in Arizona, but they have always been frustrated and thwarted at higher levels. “Don Bolles wasn’t the only frustrated person in Arizona,” said Detective McCracken. “In Arizona, everybody’s frustrated. The fact remains that only seven people have been convicted for land fraud in Arizona and they were all in on the same deal.”

McCracken’s talk of frustration is an allusion to the flagrant incompetence of the county prosecutor’s office and the county prosecutor himself, Moise Berger. Berger was appointed county prosecutor in 1968 and since that time very little prosecution has actually occurred. In the transcript of a tape secretly recorded by the Phoenix police, Moise Berger claimed that a power coalition exists in Arizona that has prevented him from prosecuting cases. He said that “the lid is on … all the way from the very top.” In the tape, Berger cited a well-known businessman and Republican party leader who, he claimed, headed the coalition. That man is Harry Rosenzweig. It is no secret that little happens in local or state politics in Arizona without the express blessing of Rosenzweig. Although he is now 68, Rosenzweig, a boyhood friend of Barry Goldwater’s, remains the most influential person in Arizona in terms of making political appointments. He loaned Moise Berger $15,000, with which Berger ran his 1968 campaign for county prosecutor.

As far as one can make out, the Arizona power coalition is an amalgam of interests—prominent lawyers, bankers, businessmen, and politicians, jokingly referred to in the Phoenix Police Department as “the Kosher Nostra”—whose power and influence run right up into the state Legislature.

More than a few of the Republic’s reporters are disenchanted. “Sure there’s a power coalition in Arizona,” said Al Sitter, “that’s definite. Nothing ever gets done. Don’s murder has changed this somewhat, but I think that will pass as soon as all this dies down. I don’t mean to be cynical, but that’s what I think.”

“After fourteen years of investigation,” said Bernie Wynn, “Don came to believe that he was batting his head against the wall. It’s the damnedest thing. The politicians don’t care. The cops are blocked. And the banks and the lawyers don’t care. They make money either way.” And, predictably, in Arizona, the citizens, the journalists would talk, the bankers and lawyers would talk, the cops in the intelligence division would talk, even the so-called criminals would talk, but the cops in homicide maintained their silence, and the politicians—politicians such as Harry Rosenzweig, Senators Barry Goldwater and Paul Fannin, and Congressman Sam Steiger—were on vacation; they were on the stumps, unavailable for comment, in meetings, out to lunch, or otherwise engaged.

Political indifference aside, perhaps the most important reason that so few of Ned Warren’s associates have been prosecuted—let alone Warren himself—is that many of them have met untimely, though “accidental,” deaths. Nothing definite can be proved, of course, but a pattern seems obvious. In 1973 William Steuer, for example, an old friend and partner of Warren’s, was found dead in his car of carbon-monoxide poisoning. Five others died in two separate plane crashes, three more were victims of heart attacks, the death of one was attributed to natural causes, and another died in a mysterious car accident.

Early last year, however, authorities believed they were closing in on Warren. Edward Lazar, the 40-year-old president of the Warren-controlled Consolidated Mortgage Company, had agreed to testify before a grand jury. It had been hoped that Lazar would provide testimony linking Warren to the underworld, but the day before he was scheduled to testify, he was found in a dark stairwell in downtown Phoenix. He had been shot four times in the chest and once in the back of the head. The grand jury was discontinued and a police official opined, somewhat belatedly, that Phoenix was no longer “a quiet little desert farming town.” Thus, in the last five years, twelve people connected with land-development schemes have died. Don Bolles may well have been the thirteenth.

“There is a general attitude around this state that anything done in the name of business is sacrosanct,” said Attorney General Bruce Babbitt. “I mean, only criminals carry guns. To attack ‘white-collar crimes’ is to be antibusiness. In Arizona, it’s ‘business as usual,’ not crime. This, after all, is the West, the land of rugged individualism. Crime happens in the East, not here.”

“This so-called white-collar crime is bullshit,” said Sergeant Jack Weaver of the Phoenix police. “They’re criminals, pure and simple. They bilk the public blind; their take is a whole lot more than that of burglars, bank robbers, or kidnappers, and they kill as easily as Capone. And the public continues to see them as businessmen. It’s incredible.”

John Harvey Adamson was an associate of Ned Warren’s, although Warren claims he did not know him very well. Their names were first connected in a trial in Seattle last year. In that trial, Warren and his son-in-law were convicted in federal court on two counts of extortion and sentenced to twelve years, but they are out on bail pending an appeal. Ned Warren has never been convicted of anything in Arizona.

Ned Warren lives in a spacious white house on the outskirts of Phoenix in the shadow of Camelback Mountain. He lives with his third wife, Barbara, to whom he has been married for 25 years. The house is for sale. Their four children have moved away and Warren says the house is too large for two people and three dogs. The Warrens maintain a Doberman, a white shepherd, and a run-of-the-mill terrier called Shoes.

As one might expect, Warren is an amiable man of considerable charm. He is short and tanned and his low, gruff voice seems to belong in another body. Over drinks in his drawing room, he confessed that he had never been able to understand what he called his “notorious reputation.” After all, was he not a man who loved his wife, his children, his thirteen grandchildren, his dogs? He loved all animals, in fact, including the little band of raccoons who slipped down from the mountain and swam in his pool. “I mean, they think it’s their swimming pool,” he said. It was clear the larceny amused him.

“I’m not given to cheap theatrics or think I’m playing the reporter’s part in a Cagney film, but I take no chances now.”

“Listen,” he said, “I talked to a reporter six, seven weeks ago and he told me his colleagues had advised him not to see me, that I was dangerous or something, that he might find his car had been tampered with. Can you believe that?” Warren smiled and spread his arms. “I mean, I don’t look dangerous, do I?” And I had to agree he didn’t. Charming men seldom do. He smiled again and told me to call him Ned. And then, referring to the deaths of those involved in the land business, he shrugged and said, “Jesus, people die in every business. It’s natural. Aren’t people allowed to die in the land business, for God’s sake?”

During those moments when the conversation lagged, Warren assured me that he was completely innocent of all accusations made against him, including his current extortion conviction. He lives quietly, he says, sees almost no one, occupies himself with his real-estate investments, and plays an occasional game of bridge, a game he learned to play in Sing Sing. He admits he is in fear for his life, hence the elaborate security system, the panic buttons, the gun he keeps near his bed. He says the name “Godfather” was an old joke perpetrated by a friend at a birthday party. He has never used it himself. Still, the name sticks.

He becomes somewhat peevish when the name John Adamson is mentioned. “You could call him an acquaintance, I suppose. I met him occasionally, but he was little more than a goon. I wouldn’t hire Adamson to plant a rose bed. After all,” he said, “Adamson’s not really the sort of man I would have in my home, is he?” Warren thinks the Bolles killing was incomprehensible. It made no sense at all. Dumb. “It’s the sort of thing an ignorant maniac would do,” he said.

He, himself, Warren said, had helped Bolles in the past. Had he not warned him that the Great Southwest Land and Cattle Company was about to go into bankruptcy? He certainly had. On another occasion he had helped Bolles settle a million-dollar lawsuit stemming from a speech the reporter had given in Sedona. “When it was over,” said Warren, “we had a cup of coffee together. Bolles thanked me and I’ll give him this. He told me that it would in no way affect the way he would write about me in the future. I told him I understood.”

Before I left, Warren gave me a solemn lecture on the waywardness of the press. “They always get everything wrong,” he said. He looked at me guardedly. “Do they mean to? I mean, did you read in the paper about me being backed by an eastern syndicate? Did you read that?” I confessed I had. “Well, listen, I have a mother. She’s 84 and now lives in New York. When I tell you she is very comfortable, believe me, she is very comfortably off. And that’s fine, but when the press talk about an eastern syndicate, they’re talking about my mother. And I don’t like it. I don’t like it at all.

“Ah well, it’s pointless talking about things you can’t do anything about.” He smiled and said good-night. Ned Warren does not think much of the Fourth Estate; he prefers not to think of it at all.

And the local press had other things to occupy their minds. It was said they intended to publish at least a story a day in the Republic until the murder was solved. And they went about their daily business with considerably more caution than they had before. Paul Dean now finds himself constantly checking his rearview mirror and inspecting his car before getting into it. “I’m not given to cheap theatrics or think I’m playing the reporter’s part in a Cagney film, but I take no chances now,” he said. Bernie Wynn remembers that on the day of the bombing he started his truck while standing outside. “I was like a kid. I turned on the ignition, quaked, and hoped for the best.” Al Sitter still drives ten or fifteen yards before he relaxes and turns on the radio. “Sure, I’m intimidated,” he said, “but I’m not going to hide in a hole. Don’s death has slowed me down. I lock the house door now and take more precautions than I did before. But it’s a nuisance, you know.” Bob Early has advised his reporters to keep in constant touch with the city desk and when possible to work in pairs. “This is not going to stop us,” he said. “We’re just going to get on with the story. My aim is to commit all our resources until we get to the bottom of this. This newspaper is not going to stop ever. Not ever.”

Nearly a month after Bolles died, Phoenix police released a deposition they had taken from attorney Neal Roberts in late June. In the deposition Roberts made a number of serious charges against Max Dunlap, 47, a wealthy contractor with extensive holdings in the Lake Havasu region, and Kemper Marley, 70, who had reared Dunlap from the age of twelve. Kemper Marley is one of Arizona’s largest private landowners, one of its wealthiest residents, its largest wholesale liquor dealer, and the largest contributor to the 1974 campaign of Democratic Governor Raul Castro. Max Dunlap and Kemper Marley were to become key figures in the Don Bolles case.

Max Anderson Dunlap is a self-made man. Much of his money has been made in land development along the Colorado River. He is the president of a dozen small companies, though he dresses like a construction worker and drives a pickup truck. “He is American Legion, rather than Phoenix Country Club,” wrote Paul Dean. He was president of Neal Roberts’s graduating class at North High School in Phoenix and knows him well. He is also a close friend of John Adamson’s and admitted that Adamson had recently asked him to help him in an elaborate scheme to defraud BankAmericard of $500,000. Dunlap said he declined. Dunlap recently borrowed $1 million from Kemper Marley, who apparently regards him as a son. Kemper Marley had been the subject of a number of Don Bolles’s articles—going back to 1967. At that time, Bolles revealed, Marley was a member of the State Fair Commission. Bolles reported that Memorial Stadium was $66,000 in debt and that Marley had a brother on the payroll. Earlier this year, Marley was appointed by the governor to a select post on the State Racing Commission. But last March, Don Bolles reported additional difficulties in Marley’s past. He mentioned the State Fair Commission again and revealed that while Marley had been an Arizona highway commissioner during the 1940s, he had been charged with grand theft, though he was later acquitted. Bolles’s articles are generally credited with forcing Kemper Marley to resign from the Racing Commission seven days after he took the job. It was said that Marley was not pleased.

Neal Roberts’s deposition and press interviews with Max Dunlap and Kemper Marley were filled with damaging revelations. A week prior to the bombing (of Bolles’s car), said Roberts, “Max called me, you know … and I hadn’t heard from him in a long time…. And he made some statement to me like, you know, ‘Old John’s a pretty good boy, if anything happens or he gets in trouble, you know, help him out, be a good guy.’ ” Roberts went on to say that he had seen Adamson and Dunlap together a few days before the bombing and he heard Dunlap make comments about “old-style western justice” in connection with Kemper Marley and Don Bolles.

On June 3, the day after the bombing, Roberts and Dunlap met at Durante Restaurant and discussed how they could raise $25,000 for John Adamson’s defense. Adamson would not be arrested for another ten days. But their versions of their conversation differ somewhat. Roberts says that Dunlap offered to raise the money. Dunlap says Roberts asked him if he would help conceal the source of the money.

The source of the money is still in question. Kemper Marley admitted to police that he had paid Dunlap $5,000 “sometime in June,” but said the money was to be used to replace “some broken machinery.” On June 10, three days before Adamson was arrested for murder, Dunlap delivered between $5,000 and $6,000 to Adamson at an attorney’s office. He claimed that the money had been delivered to his home that morning by a man he had never seen before and that he had been instructed to change the $100 notes into smaller bills and to say the money had come from Roberts.

In his deposition to Phoenix police, Roberts gave his version of the Bolles affair. “From what I understand,” he said, “Kemper was a man with a great deal of pride, who was having financial difficulties and had hoped to reverse his fortunes through service on the Racing Commission. Perhaps there was a connection with Emprise, I just don’t know, or perhaps some deal was going to give Kemper a bunch of money. If my theory bears any credence at all, it was just a kind of old-style western justice.”

In early July, one other man emerged in the case. His name was Fred Porter Jr. The father of the 60-year-old Porter had made a fortune by founding the country’s largest chain of saddle and western-wear stores. But Porter’s prosperity had vanished over the years and in May he made a formal application for commission racing permits. He hoped to regain his fortune by breaking into the Funk-Ramcorp dog-racing monopoly. At about the time Kemper Marley was being considered for a position on the Racing Commission, Porter approached Marley for assistance and Marley expressed interest in backing him. Porter also told Don Bolles about his plans; the last time they talked was minutes before Bolles drove off to the Clarendon House Hotel.

Since the bombing, Paul Dean has written several stories a week on the case. As he sees it—he ventures the theory as a personal opinion—the five men in the case now comprise a chain. “John Adamson,” he said, “is tied to Neal Roberts, who is connected with Max Dunlap. Dunlap is indebted to Kemper Marley, who knows Fred Porter. Porter approached Marley on a sensitive subject he later discussed with Don Bolles. And Bolles went to the Hotel Clarendon to meet Adamson. Full circle.” But Dean admits the circle is circumstantial.

Phoenix police, in the meantime, have said very little. Chief Detective Don Lozier, breaking a long silence, said, “It has been obvious since the day of the bombing that this crime was the result of a conspiracy by several persons, maybe as many as half a dozen persons. It doesn’t make sense that one man did this thing by himself. It is also public knowledge that there are business and personal connections linking the names of Adamson, Roberts, Dunlap, Marley, and Porter.”

But on the basis of available evidence, and with the aid of some police sources, the mechanics of the bombing appear fairly clear. According to a report in the Arizona Republic, Bolles was probably being watched by one or two men from the moment he parked his car in the Clarendon House lot. Once Bolles had entered the hotel one man walked into the lot and within seconds attached the dynamite bomb beneath the car with two magnets. Simultaneously, the second man drove to a telephone, possibly in a midtown bar, and called Bolles. Then, as Bolles backed his Datsun clear of other parked cars, leaving a line of sight between his car and the executioner, the transmitter was activated.

The theory is that the killer may have been on a balcony in the Executive Towers, the closest high rise in the vicinity. There is an ex-convict called Jack Parsons who lives there in a third-floor balcony flat. Parsons was a friend of Neal Roberts’s and knew John Adamson. The distance from his balcony to the hotel parking lot is 200 yards. The remote-control device is operable up to a mile. Parsons claims to have been out of town during the bombing. Such, at least, is the theory. The motive remains obscure.

“I don’t think the bombing was the work of an amateur as has been implied,” said Detective Lonzo McCracken. “Listen, you can send a fourteen-year-old kid off to rob a bank and if he gets away with it, people say, ‘Hey, that was the work of a pro.’ If he bungles it. it’s always the work of an amateur. The killer knew what he was doing. He checked out the Datsun and he put a big bomb under the driver’s seat. But he forgot, or he never knew, that Bolles was six feet two. Bolles would have pushed the driver’s seat back six inches or so and that’s why he wasn’t killed immediately.”

“This murder was planned,” said McCracken. “At some stage, a few guys sat around a table and discussed it. Now, what did they do? Did they kidnap Bolles, kill him quietly, and bury his body in the desert? Like Jimmy Hoffa? No, they deliberately chose loud explosives, they chose high noon in the middle of town so that everybody would know about it. Why? To make an example, a public example of him. They did it in order to intimidate, so that the next time some reporter takes it into his tiny head to snoop, he’ll have second and third thoughts.

They also must have assumed that after the initial shock the heat would pass and that people would forget like they’ve always done in Arizona. “In addition.” said Detective McCracken, “businessmen have told me that once their names appear in an unfavorable context in the paper, their businesses slump off for three or four months up to 40 percent. Now, that’s an excellent motive for murder.”

And that, for the moment, is where the case stands as Adamson’s trial begins next month. Predictably, perhaps, very little reform has occurred in the wake of Don Bolles’s death. There was much local outrage of course. Indignant editorials were written in the nation’s newspapers. It was claimed that his death inspired the first major statewide investigation into corruption in Arizona. There has been moderate reform of a few of the abuses Bolles had spent much of his life reporting. The state legislature unanimously approved the abolition of the so-called “blind trusts” which allowed secret numbered real-estate trusts to be established, thereby hiding the identity of landowners and developers. Moise Berger, the bumbling Maricopa County prosecutor, finally submitted his resignation. But Ramcorp and the Funks still control Arizona’s dog tracks, the Mafia ranges at will, and Ned Warren continues to evade prosecution. It would not have surprised Don Bolles.