Looking ill at ease in their tuxedos, The Doobie Brothers strode onstage at this year’s Grammy Awards ceremony to receive a thunderous ovation and four of the little golden gramophones that signify overwhelming success in the record business. The rockers, who later posed for snapshots with beaming, well-fed record moguls, had ushered in the ’70s with “Listen to the Music” and ridden it out with “Minute by Minute.” It had been a long decade, and the band whose very name epitomized hippie values — doobie is San Francisco slang for joint — had followed rock ’n’ roll through changing styles and passions into middle age. Now, after ten years of one-night stands, the Doobies even had their own celebrity golf tournament.

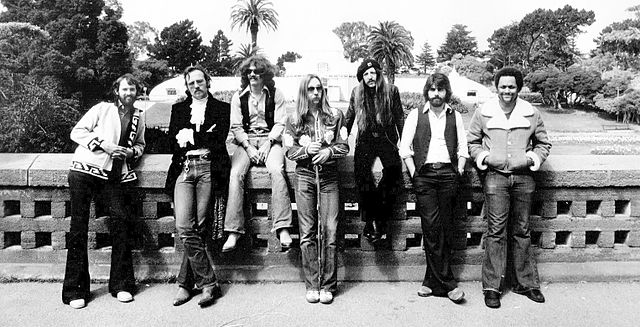

Of the seven men who stood grinning onstage, only guitarist Pat Simmons was an original Doobie; the others had followed serpentine paths to stardom. From their lives — personal and collective — a story of rock ’n’ roll survival emerges. When rock history begins to seem like a scrapbook of obituaries, The Doobie Brothers march on, to places they never expected to go.

“In this business, it’s as though you have a license to do whatever you want,” says Keith Knudsen, one of the band’s two drummers. “We used to wreck motel rooms and get wasted all the time; but now we’re incorporated, so we have group dental plans, medical plans, profit-sharing plans.” He tugs at a strap of his denim overalls, less a pop star than a barefoot executive whose firm happens to be the hottest band in America.

When Knudsen joined the group, in 1973, it was still in its infancy. It had been conceived in the winter of 1969 by singer Tom Johnston and drummer John Hartman, both of whom have since departed. The early members were bar musicians from the San Jose area, and one tradition of the band is that all the men have endured long years in honky-tonks, playing for rowdies, dodging missiles from the crowd.

“At the height of the madness, we were really into the role of hard-assed rock players. Into our hype. You know — cocaine for dessert.”

“In the early years, we played to bikers a lot,” says Simmons. “People got hurt; I remember carrying a stab victim out of the parking lot. This was at the Chateau Liberté a funky old roadhouse in the mountains near Los Gatos, the birthplace of The Doobie Brothers. But most of the bikers who came to hear us — Hell’s Angels, Gypsy Jokers — became our friends. They could identify with us because we were funky — we all rode bikes, we all dressed in leather jackets and Levis and motorcycle boots.”

In 1972, the group scored its first major hit with “Listen to the Music,” a bouncy reveille that became a staple of FM stations for years to come. The song’s innocence defined the era: “What the people need is a way to make them smile/It ain’t so hard to do if you know how.” The hypnotic title, repeated 14 times, was an ideal sound track for crash-pad bliss-outs. It was good rock: pagan Gospel. And the secret of the band’s name — pretty racy for that period — circulated in schools and communes, with knowing smiles and winks.

Follow-up hits, including “Long Train Runnin’,” “Black Water” and “China Grove,” clinched their reputation as the archetypal boogie band, and they began touring heavily about the time Knudsen joined them. “We’d tour the States four times a year, six weeks a shot, six nights a week. Those were burnouts,” he says.

Simmons elaborates: “It used to be an ongoing party. I’d go 60 hours without sleeping, totally crazed — of course, this required chemical aid, which usually was furnished. But mainly it was just the energy of playing. At the height of the madness, we were really into the role of hard-assed rock players. Into our hype. You know — cocaine for dessert.”

To certify what Knudsen calls the rocker’s license, the band engaged in standard forms of hotel sabotage. “We’d take all the objects in a hotel room,” Simmons recalls, “and turn them upside down; or put everything in the bathroom — mattresses, TV set, chairs; that was our symbol of anarchy. But after we got the first couple of bills, we stopped. Because a $9.95 item always comes back to you as a hundred bucks. And pretty soon you get tired of paying ten dollars for a 25-cent ashtray.”

These days, the Doobies’ conduct is businesslike, verging on the staid, and they are welcome guests at hotels. They journey from gig to gig in two 25-passenger planes, Martin 404s, equipped with couches, TVS, stereos and galleys. But there’s very little mania on board: Most of the Doobies don’t even smoke marijuana anymore.

Over the years, they’ve seen a fall-off in dope taking by their audiences, too, while alcohol fumes grow thicker in the arenas. “Drug use has definitely slowed down,” says Knudsen. “It used to be that you could tell what drugs were in town by the crowds — especially in Detroit. Slow clapping when Quaaludes had come into town. Since a great part of a rock audience has always been people who want to be the musicians, they want to get high the way the musicians do — whether it’s yoga or tequila.

“But nowadays I see a lot of young kids fucked up on alcohol. In those 10,000-seat arenas, after we do our final encore and they switch up the lights — it’s amazing to watch how fast 10,000 people can leave an arena — you look around at a stadium littered with liquor bottles. Whiskey and tequila, mostly.”

Rock has proved itself to be a homicidal business, no place for heroes. If you band together in 1980 — a corporate era — you’d better have more than four or six fellow zanies by your side.

Bass player Tiran Porter chips in: “It’s the old boogie-till-you-puke mentality.”

And yet those drunken kids represent only a fraction of the Doobies’ audience. On record, their principal appeal is to an upwardly mobile, young middle class. In 1975, when singer Johnston was replaced by Michael McDonald — arguably the best white singer in rock — the hand made a radical change in attack. McDonald is a blue-eyed soul crooner, a devotee of Marvin Gaye; with his lush keyboard work and urgent, sexy vocals, the group seemed to be following its audience from Woodstock to Westchester. And under producer Ted Temple-man, its sound has been oiled and buffed into a sleek and purring soft-funk machine.

The Doobies encapsulate the decade in rock. And on the afternoon I met them, they were doing the Dinah Shore show.

“Dinah Shore? Group dental plans? Golf tournaments? Hey, man, like, whither rock?”

I recognize that nagging, adenoidal voice: It’s myself, ten years ago. John at 19, scrawny and wasted, sits trimming his fingernails with a knife — a mode of hygiene he picked up from a Kerouac novel. He’s scowling. He always scowls.

“The rock band as corporation. Wow! Never thought I’d live to see the day, man.”

I look at the disheveled speed freak with a kind of nostalgic repugnance. He sits there, cocksure, a rock-will-change-the-world theorist to whom dental plans are sheer anathema and TV a sworn enemy. He loves the early Doobie Brothers for their fusion of guitar rock and campfire sing-alongs: When he’s berated in the streets with cries of “Take a bath,” “Go to Russia,” “Cut your hair,” the songs — like old labor-union anthems — give him courage. Now he feels betrayed.

“Golf tournaments. That’s the one that really tore it, man. I mean, can you picture the Jimi Hendrix Desert Classic? Or the Brian Jones Pro-Am?”

In my guise as a grownup, I try to reason with him. Both of the musicians he invokes are dead: Think of all the fiery loons who lie, unincorporated, in early graves. Rock has proved itself to be a homicidal business, no place for heroes. If you band together in 1980 — a corporate era — you’d better have more than four or six fellow zanies by your side. Simply put, a band is outnumbered.

John at 19 takes another swig of cheap Burgundy and scowls. He’s not listening. He’s still muttering the names of imaginary tournaments to himself: “The Janis Joplin Invitational — wow!”

Shaking the speed freak loose, I ride over to the studio to watch the Dinah! taping. The air is incredibly thick today, like breathing Cheez Whiz. The low studio buildings, painted bone white and peach, stand like fortresses in the midst of the smog alert. As the band’s press agent walks me to the sound stage, droning of TV specials and platinum albums, he leaves out the one saving grace of this appearance. The Doobies are using the show to promote their involvement in the anti-nuclear-power movement, and Knudsen has linked their stance with the drunken kids he sees at concerts: “Hopefully, this cause will give kids something to get straight about.” (In fact, many of the events that so nauseate the young John benefit charities. The golf tournament, for example, raised over $25,000 for the United Way.)

Backstage, the Doobies chat with their guests, Jackson Browne and Bonnie Raitt, both pioneers in the rock-against-nukes movement. Meanwhile, out front, Dinah’s warm-up man works the crowd — Pasadena retirees, widows with chiffon hair and a bevy of teenage girls. A truly Protestant-looking crowd.

Rock ’n’ roll does not require Applause signs.

The emcee comes on like a carnival barker who’s been given a little Thorazine but not enough: He snaps off his consonants like stalks of dry wheat, makes each vowel a swoon and, in general, exudes the false cheer the job requires. “If you don’t understand a joke,” he grins, “laugh anyhow and figure it out on the way back home!” He points out the locations of the Applause signs and reminds the crowd to keep their ticket stubs: “We’ll be giving away valuable prizes in a lottery after the show, to say thanks for all your clapping and laughing!”

I feel the icy presence of John at 19, reappearing like a stoned elf in the studio aisle, and this time I agree with him: Rock ’n’ roll does not require Applause signs.

“Now I want to show you how to clap. I call it TV applause — you clap short and fast, as fast as you can, and for some big scientific reason I don’t understand, it sets up a reverb effect and it sounds much better on the monitors! So all the millions of folks out there will know just how much you love Dinah and The Doobie Brothers! Ok? Let’s practice!” Everyone dutifully follows suit, checking with his neighbors to make sure he’s got it right.

It takes a while to rig up the Doobies’ amplifiers; during the wait, as a joke, the house band noodles with “Minute by Minute.” No one seems to get the aural pun, and since there’s no glowing sign, no one laughs. But they’re lavish with their short, fast applause when Dinah emerges to sing a show-opening ballad. Moments later, when the curtain parts to reveal the Doobies’ setup — two drummers’ thrones, stacks of amps on tiers, a dozen microphones, four keyboards and a jungle of wires — the crowd murmurs, unprepared for such a display of hardware. It’s a question of proportion.

As the band digs in for its opening song, the upbeat “What a Fool Believes,” I think back to an hour ago, when Porter, the bass player, sat in the front row of an abandoned theater on the lot, speaking of music in elegiac tones. “As the creative aspect of rock in the ’60s petered out,” he said in his soft, precise way, “the industry took over. Whenever you give them a vacuum, they’ll fill it. Sometimes it seems rock and the industry are at war — and rock loses, slowly but surely.” Now in midsong, Porter is at peace because he’s working the fret board of his Fender bass in that low-frequency trance reserved for bass players. But when the music stops, he looks slightly ill at ease. Porter is not showbiz.

The song ends, the audience claps on cue and though no sign flashes Squeal or Gasp, a few teeny-boppers go boldly ahead. They fling “Ooohs” like bouquets at McDonald and a few at Chet McCracken, the new drummer, whose name they don’t know: “Ooooh, drummer!” The pubescent shrieks induce a longing for the old days. Erotic and irrational, they sound more to the point than the studious clapping of elderly men in aerated golf caps.

Porter sheepishly nods and smiles, McDonald gives a tentative wave that elicits more cries and the band launches into “Minute by Minute.” Offstage, Dinah does a matronly boogie. The band is so tight, so well drilled, that the tune sounds almost exactly like the record. They finish and Dinah leads them over to the conversation area.

As they wait to converse, the press agent whispers in my ear: “Did I tell you that the Doobies are the only band ever to star in a two-part situation comedy? They were on What’s Happening! Forty million viewers.” He’s provoking the 19-year-old me into more ridicule: Jerry Lee Lewis on Bachelor Father … Chuck Berry on The Donna Reed Show….

All this TV mania should be placed in context. Rock and the tube have been at odds ever since 1956, when Ed Sullivan exorcised the demon of Elvis Presley’s pelvis and filmed him only from the waist up. We’d get the Monkees, we’d get Midnight Special — watered-down rock. And when a Hendrix or a Joplin went on talk shows, it was to deliver wasted non sequiturs that convinced their nervous hosts that some weird and unnamable force was in the air.

Now we see Todd Rundgren and Alice Cooper on Hollywood Squares, matching wits with George Gobel, and the Doobies on show after show. While there’s nothing inherently wrong about it — shut up, you little speed freak — the band seems awkward shooting the breeze with Dinah. I’ve watched them do skits on other programs and McDonald looks woefully out of place, despite his bearded good looks. The man who seems to have been hand-picked by God to sit at a keyboard and sing looks edgy being “natural” or repeating scripted jokes.

Later that day, he says, “I love the camaraderie of musicians. Frankly, what I don’t like is being pushed into the spotlight of ‘performer.’ It makes me feel like a complete fool. It doesn’t fit me. There’s no way for me to express myself in that form. I love walking into a rehearsal hall with other musicians. That part — being a working musician — I enjoy immensely. But I don’t want to be a personality. I feel like an idiot even trying.”

So why does he allow himself to be strait-jacketed into the role? It’s possible that McDonald, a shy and gifted man of 28, can’t gauge the extent of his power to say no. Industry speculation has it that one day he will be “bigger than Billy Joel,” and despite the hype inherent in the business, he stands a good chance. As a songwriter, he has a gift for the opening lyric that plunges the listener into the mood: “He came from somewhere back in her long ago …” “You don’t know me, but I’m your brother …” “Girl, as we take a long, last look at this love….” His melodies are bluesy yet ethereal and his tenor curlicues around them in a way that makes many women, as one Doobie says, “want to fuck his voice.” And although McDonald shudders at the notion of being a sex idol, the press agent persists in showcasing him that way — frequently citing his resemblance to Italian film star Giancarlo Giannini, a comparison that turns up in a suspicious number of magazine stories. (That seems a pretty weak ploy: It’s hard to imagine teenage girls in North Dakota saying, “Michael’s so cute, he’s like the guy in all those Lina Wertmuller films!”)

That night, over plates stacked high with barbecued ribs, McDonald looks much calmer. We’re talking about a subject dear to both our hearts — the bars. Two-bit roadhouses with ornate neon tubing, ratty carpets on the bandstand, rows of bottles under red lights and bouncers named Sal: the clubs that are incubators for musicians. Gigs that pay $100, split five ways, for a full night’s work — and not even that if Sal gets mad. Joints where the dancers pester you for a Pink Floyd tune or vomit on your amplifier.

Bars are schools for intimacy, for touching people firsthand; with eyes closed, you can judge your success by the pounding of feet and the sweat in the air.

“Right now,” says McDonald dreamily, “I desperately miss the clubs. I learned so much in clubs. I miss those five hours of playing loose. My whole style comes from the clubs. Because there you have two choices: to be bored stiff or to have some fun with it. For me, bottom line, I was just as happy playing the Pink Panther Room as I am right now. The real pleasure — the pleasure I can put my hands on — is the same pleasure I got when I just closed my eyes for a bunch of drunks and really enjoyed the song I was singing. I know that now.”

All the Doobies share his nostalgia for cheap dives. But the clubs, once strung along highways in bright profusion, become rarer each year. Some put on airs and become “cafés”; some are forced to close by irate neighbors; but most turn into discos. If you’ve heard comedians lament the absence of crummy night clubs for young comics, you’ll understand the wistful note in Knudsen’s voice: “Disco has knocked out the clubs where young musicians used to learn. Where they played five sets a night for two people. Where they learned to jam or play drunk on their butts. It may be leading to a hollow, unsoulful sound.”

That’s the crux of it: Without the scuzzy bars in Hamburg and Liverpool, the Beatles might have remained gifted amateurs. Bars are schools for intimacy, for touching people firsthand; with eyes closed, you can judge your success by the pounding of feet and the sweat in the air. Huge arenas blunt that sensation. As Knudsen says: “Sometimes I’ll think the audience isn’t responding and I’ll be completely wrong. In a 10,000-seat hall, you’re surrounded by monitors and a big P.A. system, and you can only hear the people in the front row.”

McDonald began playing small rooms as a child in St. Louis. “My father was in more bars than any drunk you ever met,” he says fondly, “but he never drank. He just loved to sit in with piano players. I was singing in front of people at the age of four. My father had a group called the Lincoln Minstrels, an amateur minstrel show, and I’d travel around the city with them, playing old folks’ homes — I used to love the old World War One songs.

“And then music was so important to me socially as a teenager. It was my identity. In junior high, I was at everybody’s party, because our band would play. We’d do “Mustang Sally,” “Hang On Sloopy,” the latest Sonny and Cher song. It was such a thrill; it was great to be in a band in junior high, because everyone liked you.”

McDonald toys with his spareribs, lost in a reverie. You can almost hear the young McDonald singing through a tinny mike, see the bowls of Fritos and coolers of soft drinks, feel the surge of the old songs. “I remember my parents’ looking at rock and seeing this rampaging immortality — uh, I meant to say immorality, but we thought at the time we were immortal, too — but it was really so innocent then. That innocence was such a wonderful thing. And that’s what depresses me about punk rock — I get the feeling that people are making music to make each other miserable, whereas we used to play to make each other feel good.”

At a nearby table, a guitarist serenades giggly diners with “The Impossible Dream” and McDonald returns to the present. “Boy, that’s a hard gig,” he whispers in sympathy. “Singing to tables full of families from Encino. Whew.”

At 14, McDonald began his recording career. “The local disc jockey recorded me and sent the tracks to Memphis for overdubbing,” he says. “I was on a label called Arch Records, a subsidiary of Stax-Volt, and the great soul musicians — Booker T. and the Memphis Horns, all those guys — played on my records.” Soul music was his touchstone; animated by R&B, he learned to play and sing with passion. “Soul was all that anyone knew around there, to tell you the truth. I guess acid rock was going on, but it was very far away. Ray Charles, Marvin Gaye — those were the influences.”

But McDonald never falls victim to the white-boy-singing-the-blues syndrome, which consists of false emoting, blackface vocals without depth. And he’s smart enough to know why. “Take Otis Redding. The fact that he sounds like he’s got razor blades in his throat was only a physical defect that he got around. Or Ray Charles. You listen to Ray Charles talk and by any medical standard, He shouldn’t be able to sing at all. He’s so hoarse he can barely talk. But when he sings, there’s so much to be expressed that he gets around his hoarseness and, in fact, makes it an attribute — it becomes a warmth instead of a coarseness. So a lot of white singers try to imitate the sound of those voices, instead of understanding the intent.”

The intent. McDonald has a genius for it. “To a banker, if you can’t count it, it’s not real. But that’s not so. That’s why there are guys out in the desert slowly chipping a mountain into the shape of an Indian. They see things as real that aren’t physically apparent, they don’t have to be there in their entirety. The unseen power — that’s like the emotional content of good music.”

He peers across the pyramid of spareribs as if hunting that unseen power in the room. “As much as rock ’n’ roll is an art form, it’s also a symptom — a symptom of technological society. Rock is our right to scream. The more society pushes us into a corner, the more we need it. I see it in our audiences — they need to be there. Sometimes I look out at 60,000 people and I realize it’s more than a social event: it’s a huge release, like in the days of ancient Rome. Coliseums seem to be there whenever society gets too big for its britches. “When people get lost in the shuffle, they gather in places like that to watch some epic event. It’s everyman’s way of clutching at the world.”

Clearly, in 14 years of rocking, McDonald has burned out very few brain cells. Even John at 19, humbled by the acuity of McDonald’s thought, is forced to admit that sanity may, indeed, have its place in a rocker’s make-up.

As McDonald sips at his brandy, the café’s manager comes over with a ballsy request: Like, everyone’s stoked that he’s here and, dig it, would he do a couple of tunes? McDonald stares at the snifter of brandy as if requesting its permission. “Uh, normally I would,” he says, “but I’ve had almost a whole brandy … I might embarrass myself.” He lets himself be cajoled, though, and as he walks into the bar, young women in pastel halters and guys in Hawaiian shirts abandon their food for a chance to hear him.

The house pianist’s at work in the bar, doing his James Taylor medley; when the manager whispers in his ear, his eyes widen comically and he wraps up “Fire and Rain” in a hurry. McDonald is announced to a roar of surprise. He sits at the, rickety piano, on a brief trip back to the clubs, and says, “Let’s see if I remember any songs.”

The barroom teems with aspiring stars and pickups — an L.A. version of a backwoods honky-tonk. McDonald closes his eyes, strikes a chord and sings: “

‘Together again, my tears have stopped fallin’….’ “ A perfect choice for a bar, the old C&W heartbreaker induces some women to put their heads on nearby shoulders and dream. After what McDonald’s been saying about clubs, you can’t help but hear a metaphor in the lyrics: “‘And nothing else matters; we’re together again.’” It’s a stunning performance, and the bar patrons applaud wildly, without an emcee’s coaxing; when he plays the opening figure of “It Keeps You Runnin’,” they know it right away. Doobies for a moment, they sing the chorus while McDonald’s voice soars above them. Keeping his eyes shut, he might be back in the Pink Panther or some other joint, a brilliant, unknown, playing for nothing.

The overhead for the Doobie Brothers operation runs to $65,000 a month. That means it costs $780,000 a year just to keep the mechanism at low hum and forces them to keep touring: Even with 32,000,000 records sold, they can’t assume the role of idle rich. Although McDonald can get to the heart of rock with just a booze-stained baby grand and a single microphone, the Doobies travel with four semis, the twin Martin 404 prop planes and a crew of 25. Simmons runs up $600 a month in phone bills to his girlfriend back home. The band goes, as one member says, “first cabin.” Despite brief dips in their popularity that’s pretty much how they’ve done it for the past ten years.

For John McFee, their new guitarist, the past decade has been a completely different trip. He, too, spent ten years on the road — but he toured at ground level, with a band named Clover. And Clover’s endurance record is made amazing by the fact that in ten years, virtually no one heard of it — except for a small cult in the Bay Area and other rock musicians around the country. A superb band, Clover had just dissolved when McFee got a call to replace departing guitarist Jeff Baxter.

“I was in limbo, fucked up, down to literally my last $20, and even that was borrowed. But I’ve always been loyal, and the Doobies knew me, so they figured I might not take the gig.” Not take the gig? How could anyone turn down a job with America’s top band in favor of poverty? And yet, over the years, McFee — a veteran session man as well as Clover member — had spurned offers from Boz Scaggs and Steve Miller, in order to remain in his own band. And his story with Clover plays a vital countermelocly to the Doobies’ tune.

“The last Clover tour was incredible. Thanks to various record-company assholes, we were touring in the middle of winter, back East, all of us driving in one windowed van — the whole band — in blizzard conditions, with no money. It was a kamikaze mission. We took turns at the wheel of the van, driving through Iowa at 15 miles an hour because the roads were so icy you weren’t supposed to travel — but we had to get to the next gig. We didn’t get paid for three weeks on that tour — with Clover, there was no such thing as per diems — but we got $120 a week for us to live on and share with our old ladies at home. That was it. But for three weeks we didn’t even get that. So we had to drive from gig to gig just to get money for gas and food — we couldn’t even say ‘Fuck, man, this is awful, let’s go home,’ because we didn’t have enough money for a Greyhound bus. And now here we are in North Dakota in the snow. The only food we got was the bare minimum that was called for in the rider clauses of gig contracts — a couple bottles of orange juice, maybe some peanuts, sandwiches and cheese.”

McFee, like most of the other Doobies, can stroll unnoticed down the streets of any town — a privilege few stars enjoy.

Remember, this was not some ragtag bunch of kids on downs: This was a highly regarded band, recording for a major label. As McFee tells his story, brushing his lank hair back over his shoulders, he’s remarkably matter of fact about it — because he knows it’s far more common than the Doobies’ saga, though it’s a life that few outside rock know about. “No sour grapes, man. It takes so many things to make it in this business — luck, talent, the right rack jobbers. A whole chain reaction has to happen.”

So what centrifugal force kept Clover together through ten years of degradation? “A lot of love, a lot of hope. When you’re going onstage and playing great music, you forget you’re broke — it’s a false nirvana, I guess, as far as worldly things go. I’d do gardening work when I absolutely had to. I’m classified unemployable by the state of California, I have no skills whatsoever, but I’d do odd jobs: polishing doorknobs — for real — house cleaning, scrounge work. Survival. And I’d only do that at rock bottom — I’d go through deep hunger before I’d take any day gig at all. But now that I’m married and have a kid, I have a different attitude toward starvation.”

The men in Clover were foot soldiers, urged forward through the mud by their own love of rock. Now, with the Doobies, the guitarist has entered the officers’ club. How does it feel? “At one time, I would’ve taken success and gone out and killed myself with it, either through drugs or fast cars. But thank God I was unsuccessful for so long — I’ve seen enough people go through weird head trips about success — that it’s not driving me crazy. I don’t have debts to pay off, because I never had credit. So my life hasn’t changed that much: I just don’t have to worry that my band will break up because everyone’s starving.”

John at 19, enchanted by McFee, sneaks in a question about the golf tourneys and TV shows. “I think the showbiz stuff is a way of saying, ‘Look at us in the broad daylight.’ People have come to expect certain things from rock bands — like, ‘Wow, they’re far too hip to drive a Toyota.’ ‘You shouldn’t have a golf classic, you should have a wild party and wreck furniture.’ Well, that’s one way to use money, but the Doobies would rather do charity things. You don’t have to hate your mother in order to play guitar.”

McFee, like most of the other Doobies, can stroll unnoticed down the streets of any town — a privilege few stars enjoy. That’s due in part to the frequent reshuffling of band members. When rock groups first emerged as self-contained units, in the era of the Beatles and early Stones, the unique mix of characters gave each band its aura. But the rock band — that is, the firmly bonded, roughly socialistic kind — may soon be a historical oddity. The “band” cohered as a structure in the early ’70s, taking shape from a universe of nameless studio musicians; it might not outlive the early ’80s. As attention reverts to individual stars, who are easier to merchandise, the rock group — which flowered in a time of communes, Levittowns and encounter sessions — becomes virtually obsolete.

But who mourned for soul bands? Or jazz bands? Or cowboy gangs, for that matter? The Doobie Brothers are, by necessity, as much a corporation as a rock ’n’ roll group.

Still, you’d never mistake guitarist Simmons for a vice-president of Standard Oil. Pale and thin, decked out in skintight jeans, purple jersey and snakeskin boots, he looks just depraved enough to keep up appearances. Aside from McDonald, he’s the only truly identifiable Doobie, and he still resembles the San Jose beach hippie on the covers of the group’s first records.

Tonight he’ll celebrate the decade at the Friars’ Club. Now, in the coffee shop of the Sheraton Universal, he orders a cheese omelet: He has recently become a vegetarian. “No heavy scruples or anything — but we get a lot of bad meat on the road. You get served pretty bizarre-looking stuff at four A.M. in roadside diners. I thought of all the greasy spoons I’d visited in the past ten years and it got scary. So I gave it up.”

And yet, despite bad meat and road fever, he appears sane and healthy — caged inside the flashy persona is a bright, quiet adult. How did he manage to keep it together for so long? “I don’t know that I have,” he says. “I don’t keep sane on the road. But I don’t get as ‘outside’ as I used to. I was heavily into that bikers’ concept — you know, ‘ride hard, die young.’ “ He smiles in gentle self-mockery as he repeats the axiom; then, as he glances down at the Los Angeles Times by his plate, the smile dies and he flinches.

Last night, the ecstasy-or-nothing credo that animates the best rock claimed yet another musician, a close friend of Simmons’, and with the obituary still fresh beside his coffee, he looks shaky. “I can’t help but think it could’ve been me. I’ve been on the verge, and you can’t say about the future….” He gazes out at the pool, glimmering in the morning light. “It still could be me.” Three children run past, pointing at the rock star, flushed and wide-eyed. Simmons doesn’t see. “It will be me.” His coffee turns cold. “It starts to make me feel old.”

Although streaks of gray run through Simmons’ waist-length hair, 31 isn’t ancient even by rock standards. But his line of work entails high insurance premiums. Besides the constant danger of suspect beef patties, what are the perils he faces?

“At the beginning, lots of cocaine — which I feel is the most insidious drug going. I was madly into it for several years. We got our advance for the first album and immediately ran out and scored — we cut that whole first album on it. Finally, I reached a point where it was changing me as a person. Making me paranoid. Coke is hard to see out of, once you’re inside it. It affects you even when you’re not doing it. So today I pretty much shine it on. I might do the occasional toot, but mostly I shy away.”

Yet Simmons doesn’t leave concerts with volumes of Keats and Shelley tucked beneath his arm for nights of silent contemplation. “Of course, we still get down,” he smiles. “It might be in Podunk, North Carolina, way back in the sticks, but if there are some nice kids coming around with joints, we might buy ten cases of beer and kick back for a good time. But there’s no abuse of other people — and I think that’s where rock bands get their notoriety, when someone gets abused, whether it’s a hotel manager or some chick. We’ve never been that way. Any time we get crazy, it’s done in good taste.”

He looks cheerful now as he nurses his omelet, but his friend’s death stares him in the face. To escape it for a moment, Simmons turns the page, where he encounters a long piece about The Doobie Brothers, with his face looming over the words.

At dusk, limousines polished like black mirrors begin to appear in the Sheraton parking lot. The flotilla of Lincolns carries the band and entourage to a record-company party at the Friars’ Club, which seems an unlikely venue. (Indeed, the dinner for Jimmy Stewart taking place the same night seems a more appropriate use of the club; as we enter, I fantasize about Stewart’s wandering into the wrong hall and breaking into a few bars of “ ‘Wha-wha-wha-what a, what a fool, uh, what a fool believes….’ “)

Record-company parties are, by nature, orgies of self-congratulation, lit by the dazzle of gold medallions on bared chests. This one’s a little more tasteful, since Warners’ has a reputation as the classiest of labels to uphold. And yet, with the caterers’ tables and milling crowd, the initial effect — as my companion points out — is like a “Doobie Brothers bar mitzvah.”

Porter looks as if he’s expecting the worst. “I never relax in these situations,” he says. He has put his face in neutral, stashed his lovely smile away. He did not start rocking in order to be feted with huge floral centerpieces. “The Sixties got commercialized and sold,” he had said the day before. “Most people are so involved with getting to the top, they don’t give a fuck about that spirit anymore.” And what is that spirit? “Simple: Listen to the fucking music.”

The press agent works the room, posing Doobies with TV actors for photos, kissing the air by the cheeks of executives’ wives, glad-handing at top speed, breathless. He says hello and goodbye with one all-purpose salutation: “Having a good time?” In his world, gaiety is strictly enforced.

Finally, he climbs onto the stage to make an announcement. He stands beneath the Friars’ logo — a plump monk in cowl with the motto Prae Omnia Fraternitas, which means “brotherhood above all” and seems apt. After routine thank — yous, he introduces the evening’s music: soul circa 1967, with many of its original heroes onstage. Eddie Floyd, author of “Knock on Wood,” perhaps the ultimate bar tune. Carla Thomas, who sang Tramp with Otis Redding. Rufus Thomas, her father, who did Walkin’ the Dog and loosed the Funky Chicken on America. The Memphis Horns, who supplied the brass refrains that made soul so entrancing. And to cap the bill, two real princes of rhythm-and-blues, Sam and Dave.

The reconstituted soul revue plays for nearly four hours. Its passion is so great — so exuberant and precise at the same time — that it shames 98 percent of current stuff. Rufus Thomas, an old rapscallion in an orange suit with knickers, opens the show by proclaiming, “Lots of people say they don’t like the blues — but you get them behind closed doors, put a little dip of snuff up their noses, put on some Muddy Waters, and they’ll start hollerin’ all over town!” Then he launches into a raunchy 12-bar blues, featuring a classic bit of R&B braggadocio: “Oh, baby, don’t you want to come with me? I’ve got bedsprings that can sing My Country, ‘Tis of Thee.”

By the time Sam and Dave come on to do “I Thank You and Hold On,” “I’m Coming,” the Friars’ Club has been transformed into an odiferous joint by the music. Make-up applied with excruciating care rolls down faces in rivulets; Givenchy dresses turn dark in patches. The voice of pagan Gospel returns — people who haven’t danced in years buck and prance and shake fists in the air. This is what music was before it became The Record Industry. (Or, as McDonald will say dreamily the next day, summoning his warmest praise, “It was like being in high school again.”)

The night concludes with an hourlong version of Sam and Dave’s deathless “Soul Man,” in which the principals are joined onstage by McDonald, the Jackson Five, Bonnie Raitt, Kenny Loggins and members of the Ambrosia and Pablo Cruise bands. After 45 minutes, the musicians tamp down the groove and let it simmer, the way only a great soul band can do, and the Sam and Dave number segues into “Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground),” the Jackson Five hit. The unity of the two songs points out, far better than any music critic could, how strong the influence of R&B has been. And yet, as everyone in the room knows, Sam and Dave — their voices and fervor undiminished — are not “commercial” in today’s market. “Maybe they aren’t Nazi enough for pure disco freaks,” McDonald says wryly.

But there’s something incredibly moving about this all-star jam session — as if, on this one night, only passion counts.

The morning after the party, Cornelius Bumpus stands before his hotel window, sweetly blowing tenor sax to the blond mountains of the San Fernando Valley. In a few hours, Bumpus, another rookie Doobie, will perform in the first of seven sold-out concerts at the 5000-seat amphitheater. He has been playing sax for 24 years and been a working musician (“Never out of a job,” he says with muted pride) since he was 11. Starting in a high school group whose name, the Trendo Trio, perfectly captured the mood of the era, he moved through Corny and the Corvettes and, by his rough guess, 100 other bands. Now, like McFee, he has stepped into a world of platinum albums and vast arenas. “It’s like … it’s like an ascension, man, you know what I mean?”

That night, watching Bumpus solo in the purple-and-amber spotlights, I know what he means. When he sings lead on “Long Train Runnin’” to thousands of fans, he might be thinking back a few years — to when he and two friends played that very song on a San Francisco sidewalk, for coins dropped into a felt hat. Across the stage, McFee plays his black guitar in a classic stance — legs spread, hipbones jutting, head tilted back so all you see is jaw line and hair. Simmons sprints the length of the stage to make a flying leap into the darkness, then ventures into the crowd to solo, escorted by two beefy security men. McDonald’s passionate, open-throated vocals do honor to his mentors, Ray Charles and Marvin Gaye.

And yet, despite the rousing encore of Listen to the Music, despite the letter-perfect renditions, some hint of ecstasy is missing. You sense the choreography behind each leap, the effort in the smiles: In achieving the respect of the industry, the Grammys and the wealth, the Doobies have misplaced the gift of spontaneity.

“I’m looking to get more basic, more rock ’n’ roll,” says McDonald. “I think the new members will help us get more fiery. I’m looking for a little more release.”

There’s more talent in The Doobie Brothers than on the entire rosters of some record labels. But talent alone will not provide that release McDonald seeks; some rekindling of the fire that Sam and Dave lit, some return in spirit to the two-bit clubs and rave-ups must occur, too. For a generation confused about its past and future, rock can never be merely entertainment; it must also be, as McDonald says, our right to scream.

“The emcee comes on like a carnival barker who’s been given a little Thorazine but not enough.”

[Image via WB/WC]