I finally came home. It was not too late. I always had home in my blood—Mississippi—but with this final homecoming the love I had for home stunned me.

Much of it has to do with the land, its sensual textures—one’s memory reawakened by the woodsmoke on January afternoons, the oscillation of bitter winter days and the swift false springs, the jonquils piercing through the ice, the slow-flowing rivers and the hush of the pine hills, the seared kudzu waiting to come alive again, the mad, magic Delta only 40 miles away—the immemorial beauty of the land. The sharpness of the North faded more quickly than I ever thought it would. In a moment of despair once in New York City, involving lost love and the Manhattan angst of a Sunday morning in a diaphanous autumn mist with the church bells chiming, an honored friend said: “But you have Mississippi. It never left you.”

“Certain places seem to exist mainly because someone has written about them,” Joan Didion wrote. “Kilimanjaro belongs to Ernest Hemingway. Oxford, Mississippi, belongs to William Faulkner, and one hot July week in Oxford I was moved to spend an afternoon walking the graveyard looking for his stone, a kind of courtesy call on the owner of the property. A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it, loves it so radically that he remakes it in his image.” I enjoy moving amidst the people and places Faulkner wrote about. It gives me a curious serenity, these things he owns. At 25, being a writer and a Mississippi boy, I believe his aura might have intimidated me. When asked what a Southern writer could do after the example of Mr. Bill Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor said: “You get off the tracks when the Dixie Special comes through.” At 45, I no longer want to leap off the tracks, for I have learned I own a piece of the railroad, too.

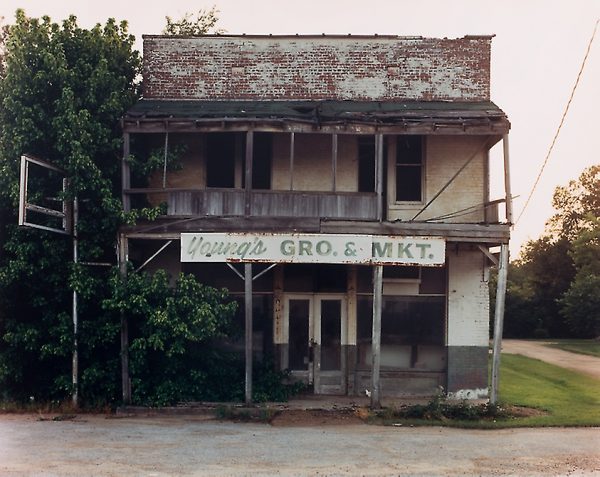

I like the way they sell chicken and pit-barbecue and fried catfish in the little stores next to the service stations, on the backroads where time has stood still. I like the way the coeds make themselves up for their classes. I like the way strangers on the Square or the Levy’s Jitney Jungle finish your sentences for you. I like the unflagging courtesy of the young, the way they say “Sir” and “Ma’am.” I like the way the white and black people banter with each other, the old graying black men whiling away their time sitting on the brick wall in front of the jailhouse, some of them wearing Rebel baseball caps. I like the intertwining of old family names, and the way houses go by those names. I like the way people remember their dead.

The caretaker of the cemetery, whose name is Bill Appleton, has become my friend. We talk about Ole Miss football. The black gravediggers sometimes join in the conversation. They say they remember the great Ole Miss teams under Johnny Vaught when Jake Gibbs was quarterback. They watch Archie Manning, another Ole Miss boy, on TV with the Saints. They recollect how Ole Miss upset Notre Dame in ’17. “Somebody once gave me a ticket to see Jake Gibbs,” Bill Appleton says. “A lot of things go on up in here at night, I’ll tell you. Oh, what these Ole Miss students do! They drink beer and copulate under the magnolias after the ballgames. The cops won’t come in here at night, though.” I ask why not. He answers with animation. “Because they’re scared, that’s why!”

My black Labrador Pete and I find strange mementos, unusual objects of obeisance or piety, or perhaps duty, left by enigmatic visitors on Mr. Bill’s grave. Many twigs of holly were deposited there after Christmas. Once we found a full pint of bourbon. An old, soggy Modern Library edition of Yeats’ poems was there one day. On Valentine’s there were several small chocolate Kisses for Mr. Bill.

It is a history-making moment, the Ole Miss-Grambling basketball game, and they are playing it right here in the Ole Miss Coliseum. It is the first Ole Miss basketball team to participate in a post-season tournament—the early round of the NIT. But much more than that, it is the first time an Ole Miss men’s team of any kind has played an all-black school. That afternoon the Grambling team, mammoth blacks trailed by a group of their fans from Louisiana, stroll around the Square, taking in the sights. Earlier that day, an Ole Miss law professor and former football star has gone to the pep squad and told them for God’s sake not to have the students dressed in the Confederate uniform there that night.

Walking toward the Coliseum with Dean Faulkner Wells (who is Bill Faulkner’s niece) and her husband Larry, I can tell it is a sellout by the traffic. It is a night for “Pappy”; the author of Delta Autumn would not have missed this momentous confrontation, so rich in irony, nor for that matter will the author of North Toward Home. “Of course, he’d be here right with us,” Dean says. “He’d absorb all of it, and he’d miss nothing.”

The Grambling team is, naturally, all black, and its small cadre of supporters, about a hundred of them are sitting en masse high behind one of the baskets. They wave shirts and pennants and yell enthusiastically: “Who dat… who dat… who dat tryin’ to beat our Gramblin’ Tii-ger!” The Ole Miss band breaks into its first Dixie, the Rebel flags are flying, and the student section counters the Grambling yell with its own: “Hotty Toddy, Gosh A’mighty, who in the hell are we? Flim flam, bim bam, Ole Miss by damn!”

An unexpected thing happens: Grambling looks awful, and Ole Miss takes a big lead. The black visitors can do nothing right. They miss easy shots, they throw the ball away time and again. The home crowd is frenetic, the Grambling students pathetically silent; their team appears hopelessly outclassed. “I’ve got a funny feeling,” Dean says. “I want Grambling to win. Pappy would too. I just know it. I can’t help it.” Things go from bad to worse for Grambling, and at halftime, Dixie resounding through the din, Ole Miss has a 16-point advantage. First I go out into the crowded hallway to talk with two Grambling supporters who have been sitting behind their bench shouting and waving various objects. By their size, they look like they are Grambling football players. “Naw,” one of them says. “We’re lawyers. We went to Jackson State. We came here just to see Ole Miss get whupped …. Naw, we don’t care about them flags and Dixie and all that. Hell, I been in Boston. It’s a lot worse in Boston. I just want to whup Ole Miss.” Then I make my way high into the stands toward the Grambling section. A student in a fraternity T-shirt stands in the breezeway with his girl. “Are you from Grambling?” I ask him. “Aw, naw, man,” he replies. “I’m a Rebel!” In the Grambling section I take an empty seat next to a student and ask him about the game. “We have a spokesman,” he says, and several of the students gesture for one of their number to come over. He is president of the senior class. He says they drove up in a special bus from Louisiana. “None of that bothers us, flags and stuff. That was a long time ago. I’m more worried about the referees. We know it’s an historic occasion. A local cop told us when we brought the bus into the parking lot.” I ask if the cop was black or white. “Well,” the president says, “he was a brother.”

A Grambling fan says, “Naw, we don’t care about them glads and Dixie and all that. Hell, I been in Boston. It’s a lot worse in Boston. I just want to whup Ole Miss.’

The second half begins; Dean is more morose than ever. John Stroud sinks two soft jump shots, and the Ole Miss lead goes to 20 points with 16 minutes to play. Grambling calls time out, and the pom-pom girls, little white lilies of Southern culture, come out for their multifarious gyrations.

Then the momentum shifts. It is Ole Miss’ turn to falter. They suddenly look tired, sick almost, missing shots and committing turnovers more frequently than Grambling in the first half. Grambling has Ole Miss at its own game—run and shoot, shoot and run. As Hotty Toddys fade, the Who dats? rise. Grambling is down to 10, six, four, two, and with 1:56 to play, they take the lead, 76–74. A quick Ole Miss shot ties the score. Dean is clapping energetically. “I still can’t help it,” she says. “I’m for us again.” With eight seconds to play, Ole Miss rebounds the ball, trying to work it to Stroud. A pass to a black Rebel guard at the key. He shoots with one second left. Ole Miss wins, 78–76.

Pandemonium. The Grambling students get up to leave for their bus. Their coach is cursing the referees. I know it’s really all right now, this Mississippi white boy does, really all right with Mississippi, anytime the Ole Miss cheering section can yell their victory yell, at the end of this curious, fateful moment, with a touch of respect and good will: “Hey, Gramblin’ … Hey, Gramblin’ … we … just … beat … the hell … outa … you!”

The juxtaposition of the town and the campus gives this neighborhood its tender, bittersweet nuance. Both Oxford and Ole Miss have the same population, about 10,000 each, and both seem more affluent from my memories of trips from Yazoo City to football games or dances in the 1950s when the surfaces were infinitely more forlorn. This is part of the new reconstruction of Dixie, maybe.

At Smitty’s where I go for breakfast, the talk during the interminable coffee breaks, among the merchants of the Square, and the legions of lawyers (why do small Southern towns have so many lawyers?), and the farmers from the farthest reaches of Lafayette County, which some know as Yoknapatawpha, is about Afghanistan, the crazed Khomeini, the Russkies—one morning coffee toasts were exchanged to the American ice hockey boys—and the next Ole Miss game, basketball or baseball, or how Steve Sloan, the young football coach, just recruited two enormous white twins from Lynn, Massachusetts, and a black flanker from the Delta who runs the 100 in 9.6 and made straight A’s in the integrated high school, and an ambidextrous black quarterback from Bruce, a few miles south on the Scoona River. At five o’clock, some of the merchants go to the back of Shine Morgan’s furniture store, behind the ovens and refrigerators, for drinks and Ole Miss sports before winding on home. They drink, not bourbon, but vodka, so their wives won’t know. This is the courthouse-square metaphor for the commuters’ pause at the Madison Avenue bars around Grand Central before the rush to the trains.

The air of youth, tonic, breathless, sexual, touches the Square. It is a contagion. On the afternoon of a game there will be Alabama or LSU or Vanderbilt pennants on the Square, streamers on the out-of-state cars in alien colors, cheerleaders in the buoyant sunshine, exuberant shouts and hee-haws and wild deep Southern embraces, punctuated here and there by the hometown Rebel yell. The SAE’s or KA’s, celebrating early before a game, as is their wont, emerge from the Gin or the Gumbo. “Hotty Toddys” reverberate off the old facades, and more Rebel yells. Mercedes-Benzes mingle on the Square with dusty pickup trucks from out in Beat Two, Snopes country. The most beautiful coeds in America drive down to shop at Neilson’s or The Image; Delta cotton money is present among the sunburnt old boys in khakis and overalls. They come to the Square with a sense of purpose, with sunswept hair and smiling faces. In the midst of the toenail-painting on Sorority Row, a voice down the hall had proposed a traditional way to get through the afternoon: “Anybody want to go buy some shoes?” As they browse through the shops facing the courthouse, there is a languorous ardor in their selections amounting almost to foreplay. When the moment of crisis finally arrives and the purchase of Pappagallos or Capezios consummated, they negligently toss their parcels in the back seats of baby-blue Oldsmobiles and compare notes—Dresden figures of pastoral gaiety—with practiced irony, on their beaus. Their mothers would be proud of them. Who knows? One of them may be Temple Drake. There may be a Popeye lurking in a corner of the Square, eyeing her with a venom.

The town watches all this, as it has in one or another form, since 1848, with a wisp of bemusement, and envy perhaps, and no little pride. The uneducated country people of Yoknapatawpha, and the counties adjacent—Union, Calhoun, Marshall, Pontotoc, Panola, Yalobusha and, of course, Lee—must view the transactions in the university classrooms with a measure of awe: people getting educated at the state university for what arcane purposes. The settlers first came to this county in the 1820s and the 1830s from Carolina and Virginia, cleared the land and made churches and roads and schools and had a courthouse square for themselves by the time of the Civil War—everything being in readiness for Federal General A. J. “Whiskey” Smith to burn it all down in 1864. With an affecting poignance, they named their town Oxford because they wanted to get the new state university to dignify their raw terrain, and they were happy when they got it, by a one-vote margin of a plenary committee of the state legislature. One of the early rules prohibited dueling during class hours. On a gray winter’s day, the atmosphere electric for a game, one perceives how Ole Miss sports is the buttress to the local emotions. All universities should be in small towns.

The campus is only a few blocks down University Avenue. Here the town and Old Miss seem to merge, little enclaves and outpockets and cul-de-sacs of youth and age. The campus does not have the intense, self-contained beauty of Washington and Lee, or Sewanee, or Chapel Hill, or the University of Virginia, but it almost does. There is a loveliness to it, an unhurried grace, with its gently curving drives, its shady bowers, its loops and groves and open spaces crowned with magnolias, oaks, and cedars and lush now with forsythia and dogwood and Japanese magnolias and the pear trees in the early spring; the ancient Lyceum at the crest of the hill, the new library with its inscription in the stone, “I believe that man will not merely endure … he will prevail,” the football stadium only a stone’s throw from all this and named Hemingway Stadium (after the law professor, not the writer) in Bill Faulkner’s hometown. A 10-year-old son of the town, a bright and sensitive boy who lives in “The Rose for Emily House” and who has the name Goodloe Tankersley Lewis, asked his mother suddenly, why do we call it Ole Miss? This took her aback, for she is an Ole Miss girl, too. Finally she said, “It means the old things.”

It is a place of authentic ghosts. Few other American campuses for me—W&L perhaps, or VMI in a different way because of the Battle of New Market, or U. Va.—envelop death and suffering and blood, and the fire and sword, as Ole Miss does. The bloodbath of Shiloh was only 80 miles away. Tupelo is closer, and Corinth, and Brice’s Crossroads where Nathan Bedford Forrest’s mad genius was exhibited, and Holly Springs where Earl Van Dorn made his brilliant raid on Grant. But Shiloh, just across the Tennessee line, fought in the springtime’s flowering of 1862, among boys untested in battle, was the nation’s first traumatic trial then—23,000 out of 100,000 dead, wounded, or missing; and they brought the wounded and dying boys down into Mississippi on trains, burying them along the railroad tracks as they died. Hundreds of boys, North and South, died in the Ole Miss hospital and the churches and on the galleries and lawns of the campus, their corpses stacked like cordwood, buried now in unmarked graves in a haunted wood behind the Coliseum.

There is a Confederate statue on the campus also, given to the university by the Faulkners as the one on the Square was. The University Grays, all Ole Miss boys, suffered bitter casualties in that war. One hundred and three of their number were the first wave of The Charge at Gettysburg. They reached the Federal entrenchments on Cemetery Ridge, and even the Federal artillery, fighting hand-to-hand with bayonet and saber. At Gettysburg, if you have ever been there, this spot is called “The High Water Mark of the Rebellion,” perhaps the closest that doomed nation ever came to winning, and it obsesses me with many strange and brooding things that it was Ole Miss boys, average age 19, who were the apex. In the year 1866, 45 per cent of the public funds of the State of Mississippi was allotted to the purchase of artificial limbs. It is a campus which has known defeat. On lonesome twilights in the Grove as I walk with my dog Pete, everything silent and deserted with the students away on spring vacation, in a palpable hush I feel the pull of this uncommon past.

In 1962, three months after Faulkner’s death, John Kennedy sent in 20,000 federalized troops during the riots over the admission of the first black student, James Meredith. Governor Ross Barnett had said, “I refuse to allow this nigra to enter our state university, but I say so politely.” Two people were killed in the polite actions which followed. One of the memorable photographs of that tragic time, only 18 years ago, is of United States airborne troops, rifles in hand, sitting in the football stadium and watching the Rebels run through their drills.

As with all places which have suffered profoundly, Ole Miss is imbued with distinction and civility. And as with the proud and unfathomable state which has nurtured it, and well over a century ago brought its university to a town named Oxford, once the terrible albatross of race was removed, once the flagrant brutalities were conquered, once the public cruelty and the cruelty of public discourse were confronted and at long last challenged, then Ole Miss could go on being what it always was, which it is today: the most complicated, histrionic, colorful, crazy, and warmly kind state university in America.

Last fall, I came to Oxford for the Ole Miss-Georgia football weekend. I drove up from Yazoo City through the Delta and got here just in time; the Ole Miss-Georgia football game began in the Gin Saloon off the Square on a Thursday afternoon and ended, more or less begrudgingly, in the bar of the Memphis airport on a Sunday night. Ole Miss plays two or three football games in Oxford every season, but since the stadium only holds 40,000, the other home games are in the larger stadium in Jackson about 150 miles south.

The Georgia fans began populating the Square by Friday afternoon, their celebrative impulses muted somewhat by their ignoble three-game losing streak. The splendid atmosphere was further desecrated by several Georgia cars with horns that played The Battle Hymn of the Republic, which is the melody of their fight song, recently adopted. On the Square one of our number, as we were en route to the fourth party of the day out on the campus, shouted at the Georgia revellers: Why not go all out and play Marching Through Georgia?, an admonition received with violent New South hostility. Will someone please put Sherman in Georgia again and give him a box of matches? a comrade suggested. There is a catfish place in the country hamlet of Taylor. After the seventh party of the day, it was to this faubourg that we repaired. In the grocery store, 13 Ole Miss partisans and one Yankee, with small Rebel flags propped up in jelly glasses around the tables, ate catfish and drank champagne, and many toasts were exchanged. An affectionate emotion seized the evening, having to do with knowing people other people knew, and other Mississippi towns we knew, and relatives long dead we knew of. Graphic descriptions of the physical doom of the Georgia Bulldogs on the morrow were set forth in the indigenous Mississippi rhetoric.

It is a place of authentic ghosts …. In 1866, 45 percent of the public funds of Mississippi was allotted to the purchase of artificial limbs. It is a campus which has known defeat.

It is no doubt a cliché, yet true, that Southern football is a religion, emanating direly from its bedeviled landscape and the burden of its past. They once drew 28,000 to their intra-squad game at the end of spring practice. There are trappings of piety in the midst of the most celebrative modes. The day of the game arrived, crisp and matchless; a fresh wind had sprung up from the Gulf. On the highways into town, the cars were bumper-to-bumper by 11 a.m. In the Ole Miss Grove, under the trees just now turning to autumnal hues, the tailgating began the night before the kickoff; the traditional Ivy League tailgating, which I have known, is an anemic ersatz. Far out in the distance, the Ole Miss band was playing Dixie, and its magic strains sounded from dozens of radios, mingling now and again with the infernal Battle Hymn of the Republic. A gray horse named Traveller II was led by a student dressed in a Confederate colonel’s uniform through the immense throng. One group of Delta planter people, as is their habitude, ate and drank from a long table immaculately draped in the best linen, with place settings of china and silver. Someone played cassettes of honored Rebel games from the past, and then Lee’s Farewell to the Army of Northern Virginia. “Here’s to the Tri-Delts of Ole Miss,” an aging lady garbed in the red-and-blue shouted handsomely from next to a Cadillac. Two men came to our Winnebago, sipping from a pint of Jack Daniel’s. They sat motionlessly on the grass. “Whoever you are,” one of them said, “we’re on the same side. To hell with them Atlanta Yankees.” Small boys with Rebel jerseys played merciless tackle, and angelic Mississippi Lolitas formed in cheerleading clusters and shouted: “Ole Miss, by damn!” Half an hour before the kickoff, a strange calm descended. “I’ve got butterflies in my stomach,” a man from Vicksburg said. Others seemed in silent prayer. An orgasmic moment was coming in the lovely little stadium up the way.

In the packed stadium, with many standing on a slight rise dotted with magnolias just behind one of the end zones, Ole Miss moved to a swift 14-point lead. The rival bands continued to taunt one another with Dixie and The Battle Hymn of the Republic. Sometimes, when both were especially exasperated, they played the two at the same time. After a 15-yard pass on a third-and-20 which got Ole Miss near midfield, the white quarterback embraced his black flanker in front of the Johnny Reb bench. Black and white Ole Miss players exchanged soul-slaps after the second touchdown. Forty thousand people, less the Georgians, stood in unison and gave the Rebel yell. Georgia’s next Battle Hymn seemed a gesture in pathos. It would have saddened John Brown.

Then, enigmatically, Georgia struck for a quick touchdown in a dread autumn’s silence fed only by the intrepid shouts of the badly outnumbered visitors and their ironic fight song. At the half the score stood 14–7, with the premonition of further Georgia momentum in the second half. Yet there was a brief rejuvenation at halftime. The Ole Miss band, majorettes, cheerleaders, and pom-pom girls, the latter in numbers sufficient to have overrun Grant at old Cold Harbor, strutted onto the Astroturf to honor America. As the band played Yankee Doodle, God Bless America and My Country ’Tis of Thee, the pom-pom girls twirled dozens of American flags, and the public address announcer spoke of America and its virtues: its democracy, its unity, its courage, its kindness, its love of all citizens regardless of race, creed or religion. Totalitarian communism was criticized. Moving into a replica of the United States, the band played a rousing America the Beautiful, slowing down with its final lustrous strains. There was a dramatic pause on the field. The Old Miss band broke into a Dixie that might have been heard in Bolivar, Tennessee. A Confederate flag 30 yards long was unfurled at midfield. Hundreds of smaller Rebel flags waved majestically in the stands. At that moment the white and black Rebels roared through the entranceway for the second half.

All for nothing. Georgia rallied and scored the decisive touchdown with 8:44 to play, 24–21. A last, desperate Ole Miss series produced four incomplete passes. The Grove, after the game, for the post-tailgating, was the largest wake I ever attended.

Here is a catalogue of things:

There are some 700 black students at Ole Miss. The pretty black coeds in abundance on the campus add to the Ole Miss tradition. Almost half the football team is black, and more than half the basketball team. (The baseball team is all white, which, with notable exceptions, is more or less true in the Southeastern Conference.) My neighbor across the street from me on Faculty Row is Cleveland Donald, a native of Mississippi who was the second black student here after James Meredith. He did his undergraduate degree here and then got a Ph.D. in history from Cornell. “I came back to Ole Miss because I’m a Mississippian,” he says, “and I wanted to come home.” He is the director of the Black Studies program. His freshman and sophomore class is large and all of the kids are from Mississippi. It saddens him that most of them will leave the state when they get their degrees: no economic opportunity, he says. The classroom is a sea of black faces. Not one white student is enrolled. The questions about writing are generally good, and eager. All these young people are products of the massively integrated Mississippi public school system, an event which took place a decade ago. Ben Williams of my native Yazoo City and now a defensive lineman with the Buffalo Bills was one of the first outstanding black athletes from that new system. So was Walter Payton of the Chicago Bears and Columbia, Mississippi. In a recent photograph of my old hometown football team, I counted 16 white boys and 16 black. They are still called the Yazoo Indians.

What do the Ole Miss blacks think of the symbols in the athletic setting: the Confederate flags, Colonel Rebel, Dixie, even the name “Ole Miss”? Lately there has been an outpouring of letters to the state’s newspapers criticizing these symbols and calling Ole Miss a “racist” school. I have kept an eye cocked to such things and have found little or no basis for them. The fraternities and sororities, of course, are white, with a handful of black Greek organizations, and there seems to be a minimum of “social” mingling, but there exists a courtesy between the races here that the North might do well to emulate. Ironically, it is the athletes who seem in the first wave of the new integrated Mississippi society. They live and eat and travel and practice and play together, and I have witnessed a genuine comradeship among them in the off-hours. A year ago Ole Miss brought in a remarkable group of young black athletes from Mississippi towns. After a time, in fact, my writer’s hunch was that the letters to the papers were nothing if not a purposeful campaign on the part of certain athletic competitors to embarrass Ole Miss in the recruiting wars.

The question lingers about these symbols of the past. After several healthy nips into the corn gourd, an Ole Miss graduate from down in Holmes County said to me one night of a basketball game, “They took away our public schools. Now they want to take away our Colonel Rebel.” There was a tone to this, not of anger, but of an almost resigned sorrow. In modern-day America, there is too much fashionable tampering with authentic tradition. At the peril which such contentions evoke, I argue that this juggling with expressions of the past is reminiscent of the way the communists are eternally re-writing history, obliterating symbols with each new guard. Finally, one could make a strong case that Dixie and the flag and the names “Ole Miss” and “Rebels,” deriving from old suffering and apartness and the urge to remember, are expressions of a mutual communal heritage, white and black, springing from the very land itself and its awesome strengths and shortcomings. As my friend William Styron once remarked, “There’s nothing wrong with the Confederate flag. The Civil War was fought over more than slavery.”

In 1971 the color barrier was broken in football at Ole Miss with the signing of Ben Williams and tailback James Reed of Meridian. In his senior year the students elected Williams “Colonel Rebel” and inducted him into the Ole Miss Hall of Fame, When he is not playing with Buffalo now, he is an officer in a bank in Jackson. In an interview with Larry Wells for his forthcoming book Ole Miss Football, Williams said:

I came to Ole Miss because it was a challenge to me, and I liked a challenge. Also, I was recruited by Coach Junie Hovious, and I admired him a lot. He helped me make up my mind, plus I felt like I could make a contribution at Ole Miss. As far as what had gone on before—in terms of race—my attitude was that I couldn’t change history: All that had already happened before at Ole Miss. If I couldn’t deal with that, I shouldn’t have come. I have no complaints about the way I was treated at Ole Miss. Nobody ever called me a nigger or anything else, and it wasn’t just because I was bigger than most people. My aim was to get an education and play football, and I accomplished that.

Buford McGee, an outstanding black halfback brought in by Steve Sloan last year, said he came here because he wanted to get a good education and because it was close to home. “I never thought about the Rebel flag or Dixie as anything but school spirit. I don’t think it was ever meant to embarrass blacks or anybody. Until the writers brought it up, I hadn’t thought about it, one way or the other. It’s the way students have always shown their support at Ole Miss.”

Ole Miss basketball was once a pariah, the mediocre Rebel teams playing to lackadaisical crowds of 1,500, many of whom were lonesome students who came to the games to do their homework. But all that changed sharply with the arrival of Warner Alford, the athletic director, who brought in a Bobby Knight protégé named Bob Weltlich as coach. This season, playing to capacity crowds of 9,000, and led by the SEC’s second leading all-time scorer John Stroud (no one will ever surpass Pete Maravich’s record), Ole Miss won more games than it had in 42 years, and carried both LSU and Kentucky down to the last seconds at home. The games in the Coliseum have become smaller, tauter versions of the home football games. The country people have taken to coming in with their wives and sons and daughters, mixing there with the fancy Delta folk, flasks in hand, who have driven two or three hours through interminable miles of dead cotton stalks to see for themselves an Ole Miss team which finally became competitive. The socializing, as in the Grove before a football game, was a thing to behold, and the flamboyance of the flag-waving crowd, and the spectacle on the floor. Alabama showed up with one white on its traveling squad, Florida with three, Mississippi State with four. LSU did not play a single white, and Auburn was not far behind. Often I would spot my son David, perambulating in the stands or along the floor with his Nikons and Canons, going a little berserk with the photographic challenge.

As part of the Ole Miss sports and literary scene this winter, George Plimpton came down to speak to my classes. Mississippi had always been a land of the hoax, and Plimpton has never been above one either. He is one of the most unusual of contemporary Americans, and one of the most charming, and he possesses an emphatic lineage. In the town of Bill Faulkner I think he was ready for anything.

An overflow audience came to hear The Plimp, at which was read a quite legitimate letter from the Governor, which I feel bears quoting:

Dear Mr. Plimpton:

“ … You are an honored guest today at our State University. Your literary and editorial genius are notable. Your athletic talent has encouraged you to play quarterback, throw baseballs, drive racing cars, block against champions, and slam cymbals together in the symphony orchestra. Your comradeship with our Southern writers in New York City, where you so graciously keep them out of trouble, has helped bring the “Grand Ole Union” back together again.

As Governor of Mississippi, I herewith extend a pardon to your great-grandfather, Adelbert P. Ames, the Republican Reconstructionist Governor of our beloved State, and present a document of safe conduct through the ghosts of old enemy lines. I pledge that you shall remain free and unmolested in the Sovereign State of Mississippi for 12 hours, beginning at 9:45 .M. today February 26, 1980, ending at 9:45 P.M. on that day, when I understand that your plane departs north from Memphis. I cannot, however, speak for the Governor of Tennessee on this matter.

With all best wishes from the people of Mississippi, I am

Sincerely yours,

William F. Winter

Governor

Plimpton was so relieved by this pardon of at least one of his great-grandfathers, as well as by his temporary safe conduct, that he gave a classic, virtuoso performance.

That evening there was a dinner for Plimpton in “The Rose for Emily House”; a gracious glass-topped table was bedecked with candles in that ancient manse. Sitting next to Plimpton was Jake Gibbs, the all-American quarterback of two decades ago and now the Ole Miss baseball coach. I had been to some of the early baseball games, where there is a line of young magnolias behind the outfield fence between the field and Hemingway Stadium. Jake chews tobacco at his coaching post at third, exhorting his charges with shouts and a whole mysterious lexicon of major league signs. Coeds sunbathe in the bleachers, bringing their individual bottles of Hawaiian coconut tanning oil. Iranian students with Ole Miss windbreakers chatter encouragement in a corner of the grandstand. On a good day, Jake will draw 1,500 or 2,000 fans, town people and country people and students for a conference game.

Now, at dinner, Jake Gibbs was telling Plimpton he chose pro baseball over football because he loved the game so much. He is one of four major leaguers turned out by Ole Miss baseball in my era (the others being Joe Gibbon of the Pirates, Jack Reed of the Yankees, and Don Kessinger of the Cubs and White Sox). He signed with the Yankees and converted himself from an infielder to catcher because the Yankees needed catchers then, and he spent 10 seasons with the Yanks. Jake and Charlie Conerly, the Ole Miss and Giant quarterback of earlier years, had a dinner for Jack Whitaker of CBS Sports when Whitaker was at Ole Miss a couple of weeks before, and Jake and Conerly had a spirited discussion on which was tougher and more important, playing quarterback or catcher, Jake saying: “I was both, and both are equals.”

All of a sudden during the dinner for Plimpton, there was a savage knock on the front door, and a tall, burly Oxford cop entered the dining room, his .38 revolver in view, his walkie-talkie blaring staccato. “Which is the Yankee George Plimpton?” he demanded. “On authority of the Governor of Mississippi, it is my duty to warn you that it is now 8 p.m., and you have exactly one hour and 45 minutes before the good will of this sovereign state vanishes. I’m ordered to escort you to the city limits.” The Plimp, after his initial surprise, turned to the group and said wistfully, “Well, I guess I better be going.” The officer unceremoniously whisked Plimpton to a limousine with a Confederate flag on its fender. Siren blazing, the police car led the way to the town line. Stopping there, the cop got out and intruded his head through the limousine window. “Never let the sun shine on your posterior in Miss’ippi after 9:45 p.m.,” he warned, and was gone. On the way to the Memphis airport, The Plimp said: “What would my great-grandpappy think?”

My best friends here are Dean Faulkner Wells and her husband Larry Wells. Dean, like her uncle and her father before her, goes to all the Ole Miss games, and like them she ardently supports the Rebels in football, basketball or baseball. Once, at a football game, she was so angered by a man in front of her who refused to stand for The Star-Spangled Banner that she hit him over the head with her Confederate flag. After her father’s death, she was brought up by “Pappy” at his house Rowan Oak, and with her cousin Jill—Mr. Bill’s daughter—and with her other cousins, she absorbed his ghost stories and enjoyed his endless entertaining of the children growing up there. Every November 10, which was the day her father was killed, Mr. Bill would go alone to the St. Peter’s cemetery and spend hours at his brother’s grave. On one November 10, in 1950, he returned home from his solitary visit when someone in New York telephoned his wife Estelle that he had won the Nobel prize.

Despite his size, Dean’s father was a superb athlete, just as is his 13-year-old grandson, his daughter Dean’s boy Jon by a previous marriage, known to us as “Jaybird”, an indefatigable spirit who wanders the town and the campus playing ball by day or night and keeping everyone posted on the Rebel statistics and who, for the life of me, is really Chick Mallison in Intruder in the Dust, either Chick or Tom Sawyer. Dean Faulkner played second base for Ole Miss and was noted for his deft fielding but weak hitting. There is a story about him in the Ole Miss-LSU game of 1931 that is still told in the town. Dean and Bill’s father Murry owned the most impressive car in Oxford, a Buick sedan convertible, and during the Depression when neither the Faulkners nor anyone else had any money, he prided himself on his car. This elder Faulkner was standing behind the backstop at the Ole Miss baseball field when his son Dean came to bat in the bottom of the ninth inning, bases loaded, one out and the Rebels trailing LSU by three runs. His father emerged from around the backstop and caught up with his son. “Drive them in,” he said, “and the Buick’s yours.” To the general astonishment, his light-hitting son proceeded to hit a fastball far over the left-fielder, and as he rounded third, there was his father, standing on the plate with the keys to the Buick in his hand. From that day on, while the father walked, Dean was seen on the streets of the town and the backroads of Yoknapatawpha, driving little white and black children all around.

One solitary midnight, I found myself alone in the Square. A cold wind was whipping in from Kansas by way of Memphis and the upper Delta; spring would have to tarry a few days. I felt the ghosts of Ole Miss football games on golden, vanished afternoons when my father brought me here as a child: of Junie Hovious and Merle Hapes and the first college game I ever saw in 1940; of Charlie “The Roach” Conerly’s heroic 50-yard passes and Barney Poole’s sliding catches, of Farley Salmon running the Notre Dame Box and Oscar “Buck” Buchanan, our Yazoo High School coach, making his tackles from linebacker. I felt the ghost of an Ole Miss girl I once loved, many years ago. I felt the ghosts too of Major De Spain and Uncle Ike McCaslin and Gavin Stevens and Lucas Beauchamp and John Sartoris and Buck Hipps and Quentin Compson and Emily Grierson and Candace Compson and Joe Christmas and Flem Snopes and Temple Drake and Dilsey and the dog Lion. Lord, Mr. Bill, I wish I had known you!

In a rush in that moment I knew, too, that all these ghosts, conjured up in the preternatural desolation of the Square, were all for me, just because I had come home. It was not too late.

[Photo Credit: Joel Sternfeld c/o The Art Institute of Chicago]