I give you Thurman Munson in the eighth inning of a meaningless baseball game, in a half-empty stadium in a bad Yankee year during a fourteen-season Yankee drought, and Thurman Munson is running, arms pumping, busting his way from second to third like he’s taking Omaha Beach, sliding down in a cloud of luminous, Saharan dust, then up on two feet, clapping his hands, turtling his head once around, spitting diamonds of saliva: Safe.

I give you Thurman Munson getting beaned in the head by a Nolan Ryan fastball and then beaned in the head by a Dick Drago fastball—and then spiked for good measure at home plate by a 250-pound colossus named George Scott, as he’s been spiked before, blood spurting everywhere, and the mustachioed catcher they call Squatty Body/Jelly Belly/Bulldog/Pigpen refusing to leave the game, hunching in the runway to the dugout at Yankee Stadium in full battle gear, being stitched up and then hauling himself back on the field again.

I give you Thurman Munson in the hostile cities of America—in Detroit and Oakland, Chicago and Kansas City, Boston and Baltimore—on the radio, on television, in the newspapers, in person, his body scarred and pale, bones broken and healed, arms and legs flickering with bruises that come and go like purple lights under his skin, a man crouched behind home plate or swinging on-deck, jabbering incessantly, playing a game.

I give you a man and a boy, a father and a son, twenty years earlier, on the green expanse of a 1950s Canton, Ohio, lawn, in front of a stone house, playing ball. The father is a long-distance truck driver, disappears for weeks at a time, heading west over the plains, into the desert, to the Pacific Ocean, and then magically reappears with his hardfisted rules, his maniacal demand for perfection, and a photographic memory for the poetry he recites…. No fate, / can circumvent or hinder or control / the firm resolve of a determined soul.

Now the father is slapping grounders at the son and the boy fields the balls. It is the end of the day and sunlight fizzes through the trees like sparklers. As the boy makes each play, the balls come harder. Again and again, until finally it’s not a game anymore. Even when a ball takes a bad hop and catches the boy’s nose and he’s bleeding, the truck driver won’t stop. It’s already a thing between this father and son. To see who will break first. They go on until dusk, the bat smashing the ball, the ball crashing into the glove, the glove hiding the palm, which is red and raw, until the blood has dried in the boy’s nose.

I give you the same bloody-nosed boy, Thurman Munson, in a batting cage now before his rookie year, taking his waggles, and a lithe future Hall of Famer named Roberto Clemente looking on. Clemente squints in the orange sun, analyzing the kid’s swing, amazed by his hand speed, by the way he seems to beat each pitch into a line drive. If you ever bat .280 in the big leagues, he says to Thurman Munson by way of a compliment, consider it a bad year.

When the Yankees bring Thurman Munson to New York after only ninety-nine games in the minors—after playing in Binghamton and Syracuse—he just says to anyone who will listen: What took them so long? He’s not mouthing off. He means it, is truly perplexed. What took them so goddamn long? Time is short, and the Yankees need a player, a real honest-to-God player who wants to win as much as blood needs oxygen or a wave needs water. It’s that elemental.

And wham, Thurman Munson becomes that player. He wins the Rookie of the Year award in 1970. He takes the starting job from Jake Gibbs as if the guy’s handing it to him and plays catcher for the next decade, the whole of the seventies. He’s named the Yankees’ first captain since Lou Gehrig forty years earlier and shows up at a press conference in a hunting vest. He wins the Most Valuable Player award in 1976, and he still wears bad clothes: big, pointy-collared shirts and dizzying plaid sport coats. Not even disco explains his wardrobe. He helps lead the Yankees from a season in which the team ends up twenty-one games out of first place to the 1976 World Series, where they fall in four straight to the Cincinnati Reds despite the fact that Thurman Munson bats over .500. Then he helps take the Yankees back to the Series in 1977 and 1978—two thrilling, heaven-hurled, city-rocking, ticker-tape-inducing wins!

And shoot if those seventies teams weren’t a circus. The Bronx Zoo. Manager Billy Martin dogging superstar Reggie Jackson, superstar Reggie Jackson dogging pit bull Thurman Munson, pit bull Thurman Munson dogging everyone, and then George—you know, Steinbrenner—the ringmaster and demiurge, the agitator and Bismarckian force who wants to win as badly as Thurman Munson. Birds of a feather. And alongside, a hard-nosed gaggle of characters—Catfish Hunter, Graig Nettles, Ron Guidry, Lou Piniella, Sparky Lyle, Mickey Rivers, Goose Gossage, Bucky Dent, Willie Randolph—who are fourteen and a half games behind the Boston Red Sox in late July 1978 and come screaming back to beat them in a one-game playoff to win the division, then trounce the Royals to win the pennant and thump the Dodgers to win the World Series. One of the greatest comebacks of all time.

And since this is New York, the press has an opinion or two. They call Thurman Munson grouchy, brutish, stupid, petty, greedy, oversensitive. It becomes a soap opera: Thurman Munson pours a plate of spaghetti on one reporter’s head and nearly kicks another’s ass. But the fans—all they see is this walrus-looking guy who plays like he’s a possessed walrus. During a game against Oakland, when he commits an error that scores Don Baylor and then he subsequently strikes out at the plate, they heap all kinds of abuse on him, and, heading back to the dugout, he just ups and gives them the finger. Hoists the finger to everyone at Yankee Stadium. That’s not family entertainment! The next day when he comes to bat, when his name is announced and Thurman Munson steels himself for a rain of boos, the same fans begin to applaud, then give him a tremendous ovation.

See why? Bastard or not, the man cares. Thurman Munson cares. Never backed down from anyone in his life—not his father, not another man, not another team, let alone fifty thousand fans calling for his head. And they love him for it. See part of themselves in him. To this day they hang photographs of him in barbershops and delis and restaurants all over the five boroughs—all over the country. A Thurman Munson cult. Tens of thousands of people who bawled the day he died.

Including me.

So, I give you a boy—me—and a pack of boys: Bobby Stanley and Jeff DeMaio, Chris Norton and Tommy Gatto, Keith Nelson and John D’Aquila. All kids from my neighborhood, playing ball in the 1970s. All of us—each of us—pretending to be someone else: Catfish Hunter pitching to George Brett or Ron Guidry pitching to Carl Yastrzemski or Reggie Jackson or Lou Piniella or Graig Nettles batting against Luis Tiant in the ninth inning of a hot summer eve in suburban Connecticut as blue shadows fall over the freshly mowed backyards.

In our town’s baseball league, I play catcher. I suit up in oversized pads and move as if I’m carrying a pack of rocks on my back. When a pitcher starts out shaky—maybe walks the bases loaded and then walks in a couple of runs to boot—I call time and trot out to the mound, kick some dirt around, chew gum. Keep throwing like that, I say, but can you try to throw strikes?

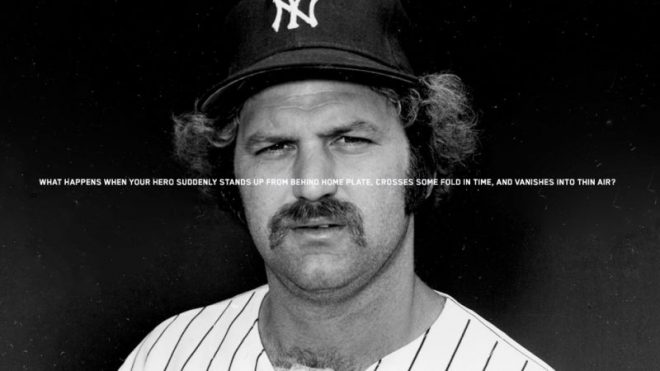

He bears a striking resemblance to the butcher at our local supermarket: the same weak chin, the same fleshy cheeks. He has a number of little tics and twitches—cocks his head, messes with his sleeves—as if being harassed by horseflies.

And, naturally, my man is Thurman Munson. Or not so naturally. I mean, why would a skinny, hairless nine- or ten- or eleven-year-old twerp identify with a gruff, ungraceful grown man who’s known to throw bats at cameramen? What shred of sameness could exist between a do-gooding altar boy and a foulmouthed, truck driver’s son? But then, just playing Thurman Munson’s position bestows some of his magic on me. Each wild pitch taken to the body, each bruise and jammed finger, is in honor of the ones taken by Thurman Munson. Each foul tip to the head becomes a migraine shared with Thurman Munson, and each hobbled knee brings a boy closer to the ecstatic revelations of a war-tested veteran, pain connecting two human beings on a level that goes beneath intellect and experience and age. Goes to a feeling. Writ on the body. We are the same dog.

At night during these muggy summers, my brothers and I watch the Yankees on television. When Munson takes the field and crouches behind home plate, or when he comes to bat, spitting into either glove and turtling his head once around, we watch. We watch him hoofing in the batter’s box like an angry bull, excavating the earth, twinkle-toeing a pile of it in circles like a ballerina, and then digging in. For some reason, his presence is mesmerizing. He bears a striking resemblance to the butcher at our local supermarket: the same weak chin, the same fleshy cheeks. He has a number of little tics and twitches—cocks his head, messes with his sleeves—as if being harassed by horseflies. Yet somewhere deep in those brown eyes, he is as calm as a northern pond waiting for ducks to land. In that place he is seeing things reflected before they actually happen, and then he makes them happen.

And there is one magnificent night—October 6, 1978—when Thurman Munson drives a Doug Bird fastball as deep as you can take a pitcher to left-center field at Yankee Stadium for a playoff home run that seals the deal: Yankees beat the Kansas City Royals 6–5 despite George Brett’s own three home runs and then beat them once more for the pennant and it’s nothing but bedlam. At the Stadium, the dam explodes; in this Connecticut suburb where the leaves are turning in the fingers of an autumn chill, four boys pump their fists, hooting and hollering and then rioting themselves—pig-piling, whacking one another with pillows, hyperventilating with happiness. A free-for-all!

So I give you a boy and a neighborhood of boys and a town of boys. I give you a suburbia of boys, and I give you five boroughs of boys, a city following a team that is a circus. A stitched-together bunch of brawlers and hustlers, cussers and bullies, led by their captain, who, as Ron Guidry puts it, can make you laugh and then just as soon turn around and put a bullet through your chest.

I’m not sure how the news about Thurman Munson gets out—maybe someone’s older brother hears it on the radio or maybe someone’s mother sees it on television. A friend dons a Yankee uniform and disappears inside his house, watching the news behind drawn curtains with his father and brother. Another friend hears about it in the backseat on the way to football practice and puts on his helmet to blubber privately, behind his face mask. Another simply won’t come out of his bedroom.

For me, August 2, 1979, has been like other summer days: swim-team practice, some baseball, lawn mowing, then down to the Sound with my buddy Mark Zengo to swim again. And that’s where I hear that Thurman Munson is dead. I’m dripping salt water, and someone’s brother says that Thurman Munson was burned alive.

When I get home, the downstairs is empty. Somewhere I can hear running water—my mom pouring a bath for my youngest brother. Something is cooking and I turn on the television. An anchorman and then the wrecked Cessna Citation, a charred carapace emblazoned with NY15, and flashing lights everywhere like some strange Mardi Gras.

It was an off day for the Yankees, and Thurman Munson was practicing takeoffs and landings, touch-and-gos. He’d had less than forty hours of experience with his new jet, and he accidentally put it into a stall. The Cessna dipped precipitously before the runway. It scraped trees, tumbled down toward a cornfield, hit the ground at about 108 miles per hour, spun, and had its wings shorn off. It crashed a thousand feet short of the runway and sailed to a stop some five hundred feet later, on Greensburg Road. The two other passengers—a friend and a flight instructor—survived, and they tried to drag Thurman Munson from the wreckage. He was conscious, probably paralyzed, calling for help. And all of a sudden jet fuel leaked, pooling near Thurman Munson, and the Cessna exploded.

Afterward, he was identified by dental records. Nearly 80 percent of his body was badly burned. The muscles of his left arm were wasted. He had a busted jaw and a broken rib, and the corneas of his eyes were made opaque by flame. He had a bruised heart and a bloody nose.

“The body is that of a well developed, well nourished, white male,” read the autopsy, “who has been subjected to considerable heat and fire, which has resulted in his body assuming the pugilistic attitude.”

The truth is I’ve had only one hero in my life. And his death coincided with a million little deaths—of boyhood, the seventies, a great Yankee team, an era in baseball, some blind faith. I didn’t go Goth after Thurman Munson’s death, I just changed a little without knowing it, in full resistance to change. And to this day, I don’t understand: What happens when your hero suddenly stands up from behind home plate, crosses some fold in time, and vanishes into thin air?

One answer: You go after him. You enter your own early thirties and, as a man, you cross the same fold and try to bring him back, if only for a moment. You go to Canton, Ohio, on a hot day not unlike the day Thurman Munson died, to the house that Thurman Munson built, a fourteen-room colonial set on a knoll, a house with pillars out front like some smaller, white-brick, suburban version of Tara, and meet Thurman Munson’s family—his wife, Diana, and the three kids: Tracy, who has three kids of her own now; Kelly, who just got married; and Michael, who was four when his father died and who himself played catcher in the Yankees’ farm system.

Their father has been gone twenty years and they still don’t exactly know who he is. Or, he is something different for each of them, and then different in each moment. An ideal, an epiphany, a hero, a betrayal. People didn’t know Thurman, says Catfish Hunter today, they just loved the way he played. And sometimes his wife didn’t know the real Thurman, either. He might visit some kids in a hospital, and later, when Diana learned about it, she’d get angry and say, Why didn’t you tell me, your own wife?

’Cause you’d go tell the press, said Thurman Munson.

Maybe I would, she said. And why not? They think you’re a spoiled ballplayer.

And Thurman Munson said, That’s why. That’s exactly why.

Show the world that he was a goofball? A sap? A romantic? The man was a koan even to himself—he couldn’t be figured or unraveled. He’d help lead the Yankees to a World Series victory—one of the proudest, sweetest moments of his life, he told Diana—then, based on some perceived locker-room slight, refuse to go to the ticker-tape parade.

There were five, six, seven Thurman Munsons, not counting his soul, and the one who mattered most was the private one, the one who came walking down a long hall like the one at the beginning of Get Smart, with doors and walls closing behind him. When he walked over the threshold after a long road trip, he’d hug his wife and say I love you in German. Ich liebe dich. He wrote poetry to her. He scribbled philosophical aphorisms. He loved Neil Diamond—“Cracklin’ Rosie,” “I Am … I Said”—played the guy’s music nonstop, incessantly, ad infinitum, ad nauseam, carried it with him on a big boom box. Thurman Munson, the grim captain, identifying with picaresque songs about being on the road, lost and alone against the world, having something to prove, falling in love.

And the kids went bananas every time he came home, hanging off him like he was some kind of jungle gym. Two doe-eyed girls and a young, red-headed son who was afraid of the dark. Thurman Munson would sit at the kitchen table and eat an entire pack of marshmallow cookies with them. He’d take barrettes and elastic bands and disappear and do up his hair and then leap out of nowhere, Hi-yahing! from around a corner, wielding a baseball bat like a sword, doing his version of John Belushi’s samurai. After the girls took a bath, Thurman Munson did the blow-drying. Then he combed out their hair. He never hurt us, remembers Kelly, the second daughter. I mean, our mom would kill us with that stupid blow-dryer and brush, and he said, I don’t want to hurt you. And he took so much time and our hair would be so smooth and he’d take the brush and make it go under and then comb it out.

When Michael, the youngest, couldn’t sleep, his father went to him. As a kid, Thurman Munson was afraid of the dark, too, but in his father’s world, Thurman Munson would lie there alone; you were humiliated for your fear, and you learned to be humiliated—often. On the day Yankee general manager Lee MacPhail came to Canton to sign Thurman Munson, the boy’s father, Darrell, the truck driver, lay in his underwear on the couch, never once got up, never came into the kitchen to introduce himself. At one point, he just yelled, I sure do hope you know what you’re doing! He ain’t too good on the pop-ups!

But Thurman Munson would sit with his own boy in the wee hours—at two, three, four, five A.M. Often he couldn’t sleep himself, lying heavily next to Diana, his body half black and blue, his swollen knees and inflamed shoulders and staph infections hounding him awake. So he’d just go down the hall and be with Michael awhile. Just stretch out in the boy’s bed. It’s all right, he’d say. There’s nothing to be afraid of.

Diana takes me to the crash site, too. Maybe takes me there to prove that she can do it, has done it, will do it again.

And maybe, too, he was talking to himself, his body having aged three years for every one he played. So that at thirty-two, after a decade behind the plate, his body was old. In the very last game he played, he started at first but left after the third inning with an aggravated knee, just told the manager, Billy Martin, Nope, I don’t have it. Went up the runway and was gone. But it was his body that was making money, realizing a life that far exceeded the life that had been given to him—or that he’d dreamed for himself. Including the perks: a Mercedes 450SL convertible, real estate, a $1.2 million Cessna Citation.

It’s a life that Diana remembers wistfully when we go driving. We visit the cemetery. We talk about the current Yankees, and she confesses that she’s just started following the team closely again, wonders if Thurman Munson means anything to today’s players, is more than just some ghost from the past. Like with her young grandkids, who know him as a photograph or an action figure.

Diana takes me to the crash site, too. Maybe takes me there to prove that she can do it, has done it, will do it again. Did it six months after the crash when the psychiatrist said that maybe Diana and the kids were always late for counseling because Diana was afraid to pass the airport. Maybe Diana is always late, thought Diana, because she has three little kids and no husband. And, right then and there, she put them in the car and drove to Greensburg Road, to the very place where Thurman Munson’s plane left black char marks on the pavement. To prove to them—and herself—that Thurman Munson doesn’t reside in this spot, five hundred feet away and forty feet below the embankment to runway 19 at Akron-Canton Regional Airport. The distance of one extremely long home run. No, she says to me now, he may live somewhere else, but he doesn’t live here.

So I go to see Ron Guidry and Lou Piniella, Willie Randolph and Reggie Jackson, Bobby Murcer and Catfish Hunter. At Fenway, I talk to Bucky Dent. I talk to Goose Gossage and Graig Nettles. I go to Tampa and sit with the Force himself, George Steinbrenner. The old Bronx Zoo, minus a conspicuous few. There are stories about Thurman Munson, a thousand, it seems. Funny and sad and inspiring. And these men—they are men now—they, too, are by turns funny and sad and inspiring.

When I visit Ron Guidry at his home in Lafayette, Louisiana, he’s working alone in the barn, chewing tobacco. He’s about to turn forty-nine, the same number he used to wear when he was pitching, when he was known as Gator and Louisiana Lightning. He looks as if he just stepped off the mound—all sinew and explosion. He works part-time as a pitching coach for the local minor league team, the Bayou Bullfrogs, and shows up for several weeks each year at the Yankees’ spring-training facility in Tampa. Mostly, he hunts duck.

He remembers his first start as a Yankee. He came in from the bull pen, nervous and wired, and Thurman Munson walked up to him and said: Trust me. That’s it. Trust me. Then walked away. As Guidry remembers it, everything after that was easy. Like playing catch with Thurman Munson. Thurman calls a fastball on the outside corner. Okay, fastball outside corner. He calls a slider. Okay, slider. Eighteen strikeouts in a game. A 25–3 record. The World Series. Just trusting Thurman Munson. Can’t even remember the opposing teams, Guidry says, just remember looking for Thurman’s mitt. Remembers that very first start: Thurman Munson came galumphing out to the mound, told him to throw a fastball right down the middle of the plate. Okay, no problem.

But I’m gonna tell the guy you’re throwing a fastball right down the middle, says Thurman Munson.

Guidry says, Now, Thurman, why’n the hell would you do that?

Trust me, says Thurman Munson. Harumphs back to the plate. Guidry can see him chatting to the batter, telling him the pitch, then he calls for a fastball right down the middle of the plate. Damn crazy fool. Guidry throws the fastball anyway, batter misses. Next pitch, Thurman Munson is talking to the batter again, calls a fastball on the outside corner, Guidry throws, batter swings and misses. Talking to batter again, calls a slider, misses again. Strikeout. Thurman Munson telling most every batter just what Gator is going to throw and Gator throwing it right by them. After a while Thurman Munson doesn’t say anything to the batters, and Gator, he’s free and clear. Believes in himself. Which was the point, wasn’t it?

I find Reggie Jackson at a Beanie Baby convention in Philadelphia, sitting at a booth. He’s thicker around the waist and slighter of hair, but he’s the same Reggie, by turns gives off an air of intimacy, then of distance. He’s here to sign autographs and hawk his own version of a Beanie Baby, Mr. Octobear, after his nom de guerre, Mr. October—a name sarcastically coined by Thurman Munson after Reggie went two for sixteen against the Royals in the 1977 playoffs, before he redeemed himself with everyone, including Thurman Munson, when he hit three consecutive World Series dingers on three pitches to solidify his legend. Manufactured by a California company, the Octobear line includes a Mickey Mantle bear and a Lou Gehrig bear—and a Thurman Munson bear, too.

I don’t like doing media, says Reggie. You can’t win, and there’s nothing for me to say. And then he starts. Says Thurman Munson was the one who told George Steinbrenner to sign Reggie Jackson. Says he never meant for there to be a rift between Reggie Jackson and Thurman Munson, that he mishandled it, and when that magazine article came out at the beginning of the 1977 season—when Reggie was quoted as saying that he was the straw that stirred the drink and Thurman Munson didn’t enter into it at all, could only stir it bad—that’s when Reggie Jackson was sunk.

I would take it back, says Reggie. I was having a piña colada at a place called the Banana Boat, and I was stirring it and I had a cherry in it, some pineapples, and I said it’s kind of like everything’s there and I’m the straw, the last little thing you need. That killed my relationship with Thurman, me apparently getting on a pedestal, saying I was the man and then disparaging him.

Near the end in 1979, says Reggie, we were getting along really well, and I was really happy about it, because feelings were rough there for a long time. You know, I wanted his friendship, and he wanted to make things easier.

Catfish got a call from George Steinbrenner and went across the street and told Graig Nettles, who was already talking to George himself, and both of them thought it was a joke at first, that someone was putting them on.

The day of the crash, Reggie had business in Connecticut. I’ll never forget that day, he says. I had on a white short-sleeved shirt and a pair of jeans and penny shoes and I was driving a silver-and-blue Rolls-Royce with a blue top. Heard it over the radio: A great Yankee superstar was killed today. And at first, I thought it was me. I wanted to touch myself. I went like that … Reggie grabs his forearm, a forearm still the size of a ham hock, squeezes the muscle, tendon, and bone. He seems moved, or just spooked by the memory of how he imagined his own death being reported on the radio. He’s driving his Rolls-Royce, and he’s here at a Beanie Baby convention. He’s hitting a home run at Yankee Stadium, and he’s here, twenty years later, going down a line of autograph seekers, shaking with both hands, as if greeting his teammates one last time at the top of the dugout steps.

Of course, everyone else remembers that day, too. Bucky Dent was told by a parking-lot attendant after a dinner at the World Trade Center and nearly fainted. Catfish got a call from George Steinbrenner and went across the street and told Graig Nettles, who was already talking to George himself, and both of them thought it was a joke at first, that someone was putting them on. Goose Gossage and his wife were in the bedroom, dressing to go see a Waylon Jennings concert. It was just, God damn, says Goose. We all felt bulletproof, and then you see such a strong man, a man’s man, die…. Then it’s like we’re not shit on this earth, we’re just little bitty matter.

Lou Piniella remembers arguing past midnight with Thurman Munson at Bobby Murcer’s apartment in Chicago a couple nights before the crash—the Yankees were in town playing the White Sox; Murcer had just been traded from the Cubs back to the Yankees—arguing about hitting until Murcer couldn’t stand it anymore, took himself to bed at about 2:00 A.M. Piniella was poolside at his house when George called. I was mad, says Piniella, now the manager of the Seattle Mariners, sitting before an ashtray of stubbed cigarettes in the visitor’s clubhouse at Fenway before a game against the Red Sox. He doodles on a piece of paper, drawing stanzas without notes. Over and over. I was mad, he repeats. I’m still mad.

Bobby Murcer, the last player to see Thurman Munson alive, remembers standing at the end of a runway with his wife and kids at a suburban airport north of Chicago where Thurman Munson was keeping his jet, declining his invitation to come to Canton, watching Thurman Munson barrel down the runway in this most powerful machine, then disappearing in the dark. Remembers him up there in all that night, afraid for the man.

And George Steinbrenner remembers it today in his Tampa office, surrounded by the curios of a sixty-nine-year life, some signed footballs, some framed photographs. He dyes his hair to hide the gray, but seems immortal. The living embodiment of the Yankees past and present. He has the longest desk I’ve ever seen.

He remembers clearly when Thurman came to his office at Yankee Stadium, flat-out refused to be captain, said he didn’t want to be a flunky for George, and George finally talked him into it, said it was about mettle, not management. He remembers flying out to Canton at Thurman’s request to see Thurman’s real estate, eating breakfast with the family. And, of course, he remembers the day. He got a call from a friend at the Akron-Canton Regional Airport, and at first he didn’t put two and two together, not until the man said, George, I’ve got some bad news. Then it hit him.

I just sat there, says George Steinbrenner now, folding his hands on his lap. Sat paralyzed. Everything about Thurman came flooding back to me—his little mannerisms and the way he played. When George could move his arms again, he picked up the phone and started calling his players. I don’t think the Yankees recovered for a long time afterward, he says. I’m not sure we have yet.

It’s 1999 at Yankee Stadium. A papery light and the good sound of hard things hitting. And yet again, there are new faces, new names: Derek Jeter, Bernie Williams, David Cone, Paul O’Neill, Roger Clemens. Luis Sojo jabbering in Spanish, cracking up the Spanish-speaking contingent, Joe Girardi chewing someone out for slacking through warm-ups (“Keep smiling, rook,” he says, “keep smiling all the way back to Tampa”), Hideki Irabu in midstretch, a big man from Japan, messing with a blade of grass, lost in some reverie, like a stunned angel fallen from the heavens, contemplating his next move.

It’s a team that last year came as near to perfection as any team in history, with a 125–50 record. If the 1977 Yankees, with their itinerant stars, were the first truly modern baseball club, then the 1998 Yankees were the first modern team to play like a ball club of yore, with no great standout, no uncontainable ego. A devouring organism, they just won.

The problem with a year like 1998 is a year like 1999: a great team playing great sometimes and looking anemic at other times. But always haunted: Paul O’Neill haunted by the 1998 Paul O’Neill; Jorge Posada haunted by the 1998 Jorge Posada. And then every Yankee haunted by every Yankee who’s ever come before. Ruth, DiMaggio, Mantle. To this day, even though the clubhouse is a packed place—Bernie Williams is jammed in one corner with his Gibson guitar and crates of fan mail; big Roger Clemens is jammed next to O’Neill, no small man himself—Thurman Munson’s locker remains empty. It stands near Derek Jeter’s, on the far left side of the blue-carpeted clubhouse, near the training room, a tiny number 15 stenciled above it.

When I ask Jeter if he remembers anything about Thurman Munson, he smiles, looks over his shoulder at the empty locker, and says, Not really. He was a bit before my time. Jeter is twenty-five, which would make him a Winfield-era Yankee fan. But when I ask Jeter if anyone ever uses it, even just to stow a pair of cleats or some extra bats or something, he looks at me quizzically and says, Uh, no, it’s like his locker, man. It still belongs to him.

In Jorge Posada’s locker, among knickknacks that include a crucifix and a San Miguel pendant, he’s got a picture of Thurman Munson, in full armor, accompanied by a quote from a 1975 newspaper article: Look, I like hitting fourth and I like the good batting average, says Thurman Munson. But what I do every day behind the plate is a lot more important because it touches so many more people and so many more aspects of the game.

It’s a sentiment that the twenty-seven-year-old Posada takes to heart. And it’s not just Posada. Sandy Alomar Jr., the catcher for the Cleveland Indians, wears number 15 on his uniform in memory of the man he calls his favorite player, a connection he was proud to acknowledge even when the Indians met the Yankees for the American League pennant last year. He says it brings him luck.

I try to imagine guys like Derek Jeter and Jorge Posada five, ten, fifteen years from now. Even as they’ve really just begun to play, they will stare down the ends of their careers, on their way to the Hall of Fame or a sad Miller Lite commercial or restaurant ownership. You play hard, hoard your memories, and then suddenly you can’t see the ball or you get thrown out at second on what used to be a stand-up double, you separate a shoulder that won’t heal or just miss your wife and children, and then you go home to Kalamazoo or Wichita or Canton, Ohio. And then who are you, anyway? Just another stiff who played ball.

Except you get the second half of your life. You get to try to be a man.

The house that Thurman Munson built first appears in a vision. One day Thurman Munson and his wife are driving around the suburbs of New Jersey when they turn a corner. Thurman Munson hits his brakes and says, Whoa, I have to live in that house! I’m serious, Diana, that’s my dream house! It speaks to some ideal, something orderly, regal, and Germanic in him, a life beyond baseball, an afterlife, and he sheepishly rings the doorbell and does something he never does. I play catcher for the New York Yankees, he says, and I have to live in this house. I mean, not now.… I just want the plans. I promise you I won’t build this house in New Jersey. This will be the only one of its kind in New Jersey. I’d build it in Canton, Ohio. This house. In Canton.

The woman eyes him suspiciously, takes his name and number, says her husband will call him. He figures that’s the end of that. But the husband calls. Invites the Munsons for dinner. By then Thurman Munson has composed himself, and the man eventually gives him the plans. And then it really begins—years of Sisyphean work. First they have to find the perfect piece of land, which takes forever. Then, instead of hiring a contractor, Thurman Munson subs out the job, picks everything right down to the light fixtures himself. He gets stone for the fireplace from New Jersey; stone for the rec room from Alaska; stone for the living room from Arizona. He wants crown moldings in all the rooms. He wants a lot of oak and high-gloss and hand-carved cabinets. In the rec room, a big walk-down bar … then, no, wait a minute, not a big bar, a small bar, and more room to play with the kids. Pillows on the floor to listen to Neil Diamond on the headphones.

He flies in on off days during the season to check how things are going. But they’re never going well enough. Thurman Munson rages and bellyaches. He throws tantrums. He has walls torn down and rebuilt. He chews the workers out like Billy Martin all over an ump. Like his own father all over him. The guys start to hide when they know he’s coming. Sure, you want your house to look nice, but this guy’s a maniac. He’s dangerous. He’s Lear. He’s Kurtz. He’s a dick.

And the stone keeps coming. From Hawaii, Georgia, Colorado …

Then finally it’s done. It’s 1978. Thurman Munson’s father, the truck driver, has abandoned his mother, moved to the desert, is working in a parking lot in Arizona, a dark shadow in a shack somewhere, and Thurman Munson moves his own family into the house that Thurman Munson built.

Something lifts off his shoulders then—after all the tumult, after the two World Series victories, after his body has begun to fail, after the constant rippings in the press. And yet, he’s also become more inward and circumspect. He doesn’t hang out with Goose and Nettles and Catfish for a few pops after games anymore. No, many nights, nights in the middle of a home stand, even, he goes straight to Teterboro Airport, where he keeps his plane, and flies back to Diana and the kids, follows the lights of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the towns of Lancaster and Altoona and Clarion flashing below and the stars flashing above, until Canton appears like a bunch of candles. Sometimes he’s home by midnight.

And here’s the odd thing now: There’s always someone in the house when he comes through the door. There’s Thurman Munson and Thurman Munson’s wife and Thurman Munson’s kids, but there is someone else, too. A part of himself in this house. A presence, a feeling around the edge of who he is that waits for a moment to penetrate, to prick his consciousness, to change him once, forever.

Until it does: one summer evening on a day with no game when Thurman Munson has had three home-cooked meals and the family has finished dinner and the kids are playing. Diana is in the kitchen tidying, washing dishes. Thurman Munson is wearing a blue-and-white-checked shirt and gray slacks. He rolls up his sleeves, lights a cigar, goes out back, and lounges in a lawn chair, feet up on the brick wall. He’s never one to relax, always has a yellow legal pad nearby, running numbers for some real estate deal. But it’s that quiet time of evening, a few birds softly chirping in the maples, blue shadows falling over the backyard, the sweet scent of tobacco. Thurman Munson just gazes intently at the sparklers of lights in the trees, a wraith of smoke around him.

Diana glances out the kitchen window and sees his big, blue-and-white-checked back, sees Thurman Munson shaking his head. A little while later she looks out the window and again he’s shaking his head. And then again, until she can’t stand it any longer, and she barges out there and says, What are you looking at? Why are you shaking your head? Thurman Munson doesn’t seem to know what to say, but when he looks at her, his eyes are all lit up and he’s crying. It’s one of the only times she’s ever seen him cry.

I just never thought any of this would be possible, he says. And that’s it. For one brief moment, the man he is and the man he wants to be meet on that back lawn, become one thing, and then it just overwhelms him.

After the crash, the psychiatrist told Diana to get rid of her husband’s clothes quickly or it would just get harder and harder. So that’s what she did, she got rid of Thurman Munson’s clothes, the hunting vest and bell-bottom pants, the bad hats and suits and coats. It took an afternoon, going through his entire wardrobe. Sometimes it made her laugh—to imagine him again. Sometimes it was harder than that. And she got rid of almost everything.

But that blue-and-white-checked shirt—she kept that.

I go to Catfish Hunter’s farm in Hertford, North Carolina, not far from the Outer Banks, on a swampy summer night. He owns more than a thousand acres, grows cotton, peanuts, corn, and beans, and after retiring at the age of thirty-three, this is where he came. Always knew he was going to come back here after baseball, just thought his daddy would be here, too. But he died a week before Thurman Munson. The darkest weeks of Catfish’s life. Out in the fields, living with the ghost of his father, sometimes something would pop into his mind and he would remember Thurman.

He could make a $500 suit look like $150, says Catfish now, then he smiles. In the past year, the fifty-three-year-old former pitcher has been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease. Started as a tingle in his right hand when he was signing autographs down at Woodard’s Pharmacy for the Lions Club in the spring, then he had to use two hands to turn the ignition on his pickup when he went dove hunting, by Halloween knew something was seriously wrong, and now his arms hang limply at his sides. Seems farcical and cruel. The same arm that won 224 games, that helped win five World Series rings, that put him in the Hall of Fame, lies dead next to him. Wife and kids and brothers and buddies help feed him, take him to the pee pot. And then no telling what the disease will do next.

If Thurman had played five more years, he’d own half the Yankees, says Catfish. Everybody liked the guy. The whites, the blacks, the Hispanics. We sit on a swing by the side of the house, the fields stretching behind us, family and friends out on the front lawn watching Taylor, the four-year-old grandchild, bash plastic baseballs with a plastic bat. A fly buzzes Catfish, but he can’t lift his arms to wave it away. Even if he could, I’m not sure he would now. Remembering Thurman Munson keeps bringing Catfish back to his father, the proximity of their deaths, a double blow with which he still hasn’t really come to terms. And his own condition—a thing suddenly hurtling him nearer to the end.

Every time I came home from playing ball, says Catfish, the first thing I always did was go over and see my dad. He lived seeing distance from here. My wife said, You think more of your daddy than you do of me. And every day that we went hunting, my wife would fix us bologna-and-cheese or ham-and-cheese sandwiches and every day I ate two and he ate one. When Thurman died, his uniform was still hanging in his locker. I just thought he was going to come back. Every time I walked in the clubhouse, I thought he was coming back.

His eyes well with tears, he seems to look out over the road, reaching for his daddy again or Thurman Munson, then shakes his head once. Remembers a story: pitching to Dave Kingman in the All-Star Game, the same Dave Kingman who hit a Catfish change-up in a spring-training game for a home run the length of two fields, and here he is again, and here is Thurman Munson calling for a change-up again. Catfish shakes it off and Thurman Munson trundles to the mound, says, Gotta be shitting me, won’t throw the change-up. Millions of people watching tonight that’d love to see him hit that long ball. Oh, let him hit it as long as he can! Munson goes back, flashes the change-up, Catfish throws a fastball and pops him up. When he goes to the dugout, Thurman Munson shakes his head. Gotta be shitting me, he says, won’t throw the change-up, then walks away.

Yes, Thurman Munson might put you on like that, but Catfish says he only saw him truly angry once. Saw the napalm Thurman Munson, the one that sought to undo the other Thurman Munsons. Some corporate sponsor gives Munson and Catfish a white Cadillac to drive around for the summer, and the two cruise everywhere in it. One night after a game, they walk out and see the front windshield is smashed, all these glass spiderwebs running helter-skelter. Catfish isn’t happy, but Thurman Munson starts cussing and ranting and raving. He says, I’m gonna kill whatever sons of bitches did this! He goes berserk. Stalks toward the Caddy, opens the trunk, and suddenly pulls out a .44 Magnum revolver.

Catfish is standing in front of the Caddy, and when he sees Thurman Munson with that .44, his eyes nearly pop out of his head. He goes, Holy shit, Thurman, you got a gun!

I’m going to kill them, says Thurman Munson.

Kill who? says Catfish.

Kill whoever it is I see on the other side of that fence.

Don’t load that gun, says Catfish.

Yes, I am, says Thurman Munson. And he does—then raises it, points it at shadows moving behind the fence, and fires. Crack!

Shit! yells Catfish.

Thurman Munson fires at the shadows again, and again—Crack! Crack! Without thinking, Catfish rushes him, gets his own powerful paws on the Magnum, and wrestles it away. Please, God, don’t let someone be hit, prays Catfish out loud, because now my fingerprints are all over that damn thing.

I didn’t hit anybody, says Thurman Munson. But I’m gonna run them over.

And that’s what he tries to do. He gets in the car and barrels through the parking lot, people leaping out of the way.

God damn, you’re crazy, says Catfish. Even today, Catfish can’t figure it out. Could have ended up killing someone, thrown in prison. The man he says he loves actually shot at those shadows.

It’s getting on toward evening now. When it’s time for dinner, Catfish’s wife comes and fetches us. Without my knowing it, I have been invited to stay. Because of Thurman Munson. And so I stand with Catfish Hunter and his family before a table full of food—lobster, a pan of warm corn bread, mashed potatoes, and slaw—on a June night in North Carolina, cicadas droning, heat releasing from the earth. Twenty of us gathered in a circle—fathers and sons, mothers and daughters—and everyone joins hands. Even Catfish, though he can’t raise his at all. His wife takes his right hand and, following her lead, I take his left. A heavy, bearlike thing, warm and leathery and still callused from farming. The hand of a man. I bow my head with all of them. And we pray.

I give you a boy and a man, a son and a father—and then the father’s father. Together for the first time, at Thurman Munson’s funeral. The son wears a miniature version of the Yankee uniform that his father wore. The father lies in a coffin. And his father, the truck driver, has magically appeared from Arizona, sporting a straw sombrero. For a thin, hard man, he has a large nose.

It’s the biggest funeral Canton has seen since the death of President McKinley, thousands gathering at the orange-brick civic center, hundreds more lining the route as the hearse drives to the cemetery. Thurman Munson’s old golf buddy, a pro, waits on a knoll at the local course and doffs his cap when Thurman Munson passes. All the Yankees are there. Bobby Murcer and Lou Piniella deliver the eulogy. And that night Murcer, who’s not penciled into the starting lineup, asks to play, knocks in five runs, including a two-run single to win the game, and limps from the field held up by Lou Piniella, then gives his bat to Diana Munson. A bat kept today somewhere in the house that Thurman Munson built.

When the hearse arrives, Thurman Munson is wheeled into a mausoleum, followed by his family: Diana, the kids, Diana’s mother, Pauline, and Diana’s father, Tote, who over the years had become Thurman Munson’s best friend. The old man, the truck driver, stands apart. When he’s asked by a stranger how long it’s been since he last saw his son, he says, Quite a while. Thurman never found himself, he says.

Every day he plays in the shadow of his father. He won’t let himself be outhustled, outplayed, outthought, if he can help it.

Then he does something disturbing. The truck driver holds an impromptu press conference, not more than fifty feet from Thurman Munson’s coffin, telling a group of reporters that his boy was never a great ballplayer, that it was really him, Darrell Munson, who was the talent, just didn’t get the break. Later, he approaches the coffin and, according to Diana, addresses his son one last time, says something like: You always thought you were too big for this world. Well, look who’s still standing, you son of a bitch.

That’s when Tote can’t stand it anymore. He rises from his seat, meaning to tear him limb from limb. The police jump in and the old man, Darrell, is escorted from the cemetery, vanishes again, back to the desert, back to a shadow in a shack somewhere.

And what happens to the son? Michael Munson is graced and doomed by his own name. He grows up and wants to play baseball, builds a batting cage in the backyard. As a sophomore in high school, he can’t hit breaking balls or sliders, but he busts his ass until he can. He wills himself to hit. And then he does. He goes to Kent State, his father’s alma mater, and stars as an outfielder. In 1995, the Yankees sign him to their rookie league, switch him to catcher. Must think it’s in the genes.

He goes over to the Giants and then winds up in Arizona, in the desert. He wakes at dawn, gets to the ballpark an hour and a half before everyone else. He’s pale-skinned and freckled, has bright, clear eyes, the body of his father. He puts on his uniform and lifts, then runs and stretches. His arms bear bruises, his knees feel like grapefruits, the back of his neck is sun-scorched.

And every day he plays in the shadow of his father. He won’t let himself be outhustled, outplayed, outthought, if he can help it. Because now when he goes back and watches those old Yankee games, he can see what his dad was thinking, how he called a game, how his quick release came from throwing right where he caught the ball, how he had as many as ten different throwing motions depending on the ailment of the day, how he did a hundred little things to win. He can see his dad jabbering incessantly and smacking his mitt on Guidry’s shoulder after a win. He can see how his teammates looked up to him. And it’s something like love. He sits and watches his dad crouch behind the plate, in a tight situation, maybe bases loaded and the Yankees up by a run, maybe Goose on the mound, the season on the line, and Thurman Munson, the heart and soul of those seventies teams, doesn’t even give a signal. Just waves like, Bring it on, sucker. Trust me.

So I give you a boy—me—and a pack of boys and neighborhoods of boys who have grown into men. We are now stockbrokers and real estate agents, computer consultants and a steel guitarist for a country-western band. Some of the best of us are gone, buried in our hometown cemetery, and the others are fathers or fathers to be or have dreams of kids. My brothers are all lawyers, and I live in a house that I own with a woman who is going to be my wife.

I did cry the day Thurman Munson died. I’m glad to admit it. And I cried the night I left Catfish Hunter in North Carolina, driving straight into a huge orange moon. I hadn’t cried like that in years, but I was thinking about them—and myself, too—and I just did.

What happens when your hero suddenly stands up from behind home plate, crosses some fold in time, and vanishes into thin air?

You go after him.

So I give you Thurman Munson, rounding third in the half-light of the ninth inning and gently combing out the hair of his daughters. I give you Thurman Munson, flying over America, looking down at the same roads his father drives, and returning home to his wife, speaking the words Ich liebe dich. I give you Thurman Munson shooting at shadows and leaping into the arms of his teammates. I give you Thurman Munson beaned in the head and sleeping next to his son again.

I give you the man on his own two feet.

[Featured Illustration: Jim Cooke]