Tom Wolfe died a couple of days ago and if you have never read his entertaining and much-celebrated non-fiction, well, now is as good a time as any to dig in. Start with the relatively straight-forward “The Marvelous Mouth of Cassius Clay” featured in the October 1963 of Esquire, just months before the fighter beat Sonny Liston to become heavyweight champion:

Cassius lets you know in a wide assortment of ways that his big talk is an act. He says it straight out. He says it obliquely with the bit about, “You better not lemme go.” He says it ironically, and perhaps unconsciously, when he sits in a $160-a-day hotel suite, looking out over city lights, and cajoles a battery of hip New York girls into standing up and being counted on the side of beans and bread as apostrophized by an alley singer nobody ever heard of. But it is also true that now he has had the view from the top of the mountain, as the phrase goes. It is doubtful that he is going to be able to settle, psychologically, for anything less. He is only twenty-one years old, but the latter-day career of Cassius Clay is going to be one of the intriguing case histories of American boxing or show business or folk symbolism or whatever it is that he now is really involved in.

And then there’s this little ditty—on the nature of Sin—that he wrote for The Saturday Evening Post in 1965. Also, this meaty excerpt from Richard Kluger’s seminal book about the New York Herald Tribune:

Used to the tight space requirements of the Post in Washington, Wolfe would ask how long he should make his pieces, and day city editor Dan Blum would tell him, “Until it gets boring.”

Next, strap in for a ride in Wolfe’s funhouse with “There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy Kolored (Thphhhhhh!) Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby…”—and then check out how the story came to be from its editor, Byron Dobell:

SMILING THROUGH THE APOCALYPSE – BYRON DOBELL CLIP from Tom Hayes on Vimeo.

The hijinks were just beginning. Check out this lede to a 1964 piece Wolfe wrote for Esquire on Las Vegas:

And now you’re ready for a pair of Wolfe’s crowning achievements: “The Last American Hero is Junior Johnson! Yes!” (Esquire, March 1965), and “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s” (New York, June 8, 1970), a loving portrait of an American icon and a satirical takedown of another. Both stories are all-time greats.

(Another one that fits nicely into his Greatest Hits collection is the New York feature “The ‘Me’ Decade and the Third Great Awakening”.)

A few years later, Wolfe co-edited of an anthology of the so-called New Journalism, a term Wolfe admitted was half-horseshit. But he was a master promoter as you’ll see in “The Birth of ‘New Journalism’; An Eyewitness Report” (New York, February 14, 1972) and “Why They Aren’t Writing the Great American Novel Anymore” (Esquire, December, 1972).

Not everybody was convinced (and Wolfe had no shortage of critics). According to the esteemed critic, Wilfrid Sheed:

The worst news to come this way in some time (if you exclude the recent unpleasantness at the polls) is that Torn Wolfe is serious. I don’t mean artistically serious—I always assumed that—but, you know … serious. He has been carrying on at some length lately about his baby, the New Journalism, but with none of his old nerve‐racking audacity. More like a … grandfather, for God’s sake.

This could have several dire consequences, even beyond the endless panel discussions it has already launched on “Is There a New Journalism,” all of which are on Wolfe’s head. It has also robbed us of one of our most resourceful literary performers in the middle of his act: rather as if Groucho were to come back at Mrs. Rittenhouse with a lecture on comedy. That sort of thing should be postponed till dotage, at the very earliest.

Wolfe at his best seemed to be impenetrable. No criticism could pierce the white suit or provoke a straight answer. One assumed that the effect was calculated, but one couldn’t quite be sure. That is the essence of eccentricity‐as‐art (see Tiny Tim). He is kidding, isn’t he? The clown bats his lids, seems not to hear the question. Gooses you, one way or an other.

…Let’s allow that the boys he cites are doing something new in close‐to‐the‐skin reporting. But did anyone ever read Wolfe for that? It is actually a quaint feature of his gift that readers assume his reporting to be inaccurate, even when he swears it isn’t.

He claims that he and his friends evoke a subject for you as it really is, and maybe that’s what his friends do. But in his own case, this is like El Greco boasting about his photographic accuracy. We enjoy Wolfe (or not) precisely for the distortion. We never supposed the Bernsteins were really like that. All the details may have been right in “Radical Chic,” as Wolfe ponderously argues—and as his critics ponderously argue back—but the result was gorgeously unreal. Why? Because the Bernsteins probably don’t give a damn about their canapés or what shoes they’ve got on. Wolfe does and, like the artist he is, makes you share his values. In this sense, Wolfe’s Bernsteins are like the cartoon George Grosz’s Germans, part them and mostly him. The real subject is his imagination, as affected by the Bernsteins.

…By muttering “Reporter, I’m a reporter” over and over, he reminds his nose to stay down near the details where it works best. But upon these truths he imposes his own consciousness, his own selection and rhetoric, and they become Wolfe‐truths, and he is half way over the border into the hated Novel. He ingenuously wonders why no novelist has ever used the reporting he did on the West Coast Beats in Electric Kool‐Aid Acid Test, but doesn’t realize he has already used it himself. That book may well be the best literary work to come out of the Beat Movement, yet the material is quite inaccessible to anyone else. I pity the poor writer following Wolfe to the Coast hoping to find what he found. It is all in Wolfe’s skull. The Beats probably weren’t like that at all, as far as anyone else could see. In fact, rumor has it that all they wanted to do was splash his white suit. Like everybody.

So let’s hear no more social realism out of Wolfe, that supreme fantastist. The Truman Capotes may hold up a tolerably clear glass to nature, but Wolfe holds up a fun‐house mirror, and I for one don’t give a hoot whether he calls the reflection fact or fiction. But Wolfe seems to feel burdened by his uniqueness and is eager to be one of the boys in the pressroom again, so he has enrolled the Dublin‐type storyteller Jimmy Breslin in his raggle‐tag school and roaring Pete Hamill, who is not primarily a reporter at all but inspired street lawyer, and just about any writer he can find under 40. All he has done is give literary glamour to some good journeyman reporters, and some journalistic glamour to the essayists, and provide some company for himself.

Of course, Wolfe eventually turned to fiction and scored his biggest success with a novel—Bonfire of the Vanities. But not not before he delivered what Tom Junod considers Wolfe’s greatest magazine story, the long 1983 Esquire profile of Robert Noyce, who invented the integrated computer chip and founded Intel. According to Junod:

There is very little Wolfean hyperbole, comic or otherwise, because there is very little satire. The hyperactive set pieces that have always been his signature? Hell, there are not even any scenes, not to mention no quotes and no sourcing. The whole thing reads like a more journalistically conventional version of a Tom Wolfe story … except of course it dispenses with journalistic conventions altogether. It runs fifteen thousand words, at least, and yet it feels like an exercise in taking out rather than putting in, as though Wolfe set himself a challenge when writing it—as though he wanted to see what was left of a Tom Wolfe story when all the Tom Wolfe was taken out.

For more on Wolfe, check out The Rolling Stone Interview with Chet Flippo (August 21, 1980) and The Art of Fiction Paris Review interview with George Plimpton (Spring, 1991). Going back, don’t miss this terrific 1966 interview with Vogue. While you are there, do yourself a favor and savor Corey Seymour’s affectionate essay about Wolfe.

It is funny to think of words like “heartfelt” and “Tom Wolfe” but he was, by all accounts, a gentleman and people seem to remember him fondly—like Kurt Anderson, in this lovely remembrance for the Times. James Rosen details Wolfe’s early days when he briefly worked at The Washington Post, Flashbak recounts Wolfe’s epistolary friendship with Hunter Thompson, and Architectural Digest features a sweet letter Wolfe once wrote growing up in Richmond, Virginia.

As for big features, 2012 Ed Caesar had a smart profile of Wolfe for British GQ, which includes a tasty morsel about Wolfe and Gay Talese reporting stories for their respective papers (Herald Tribune and the Times) the day JFK was assassinated.

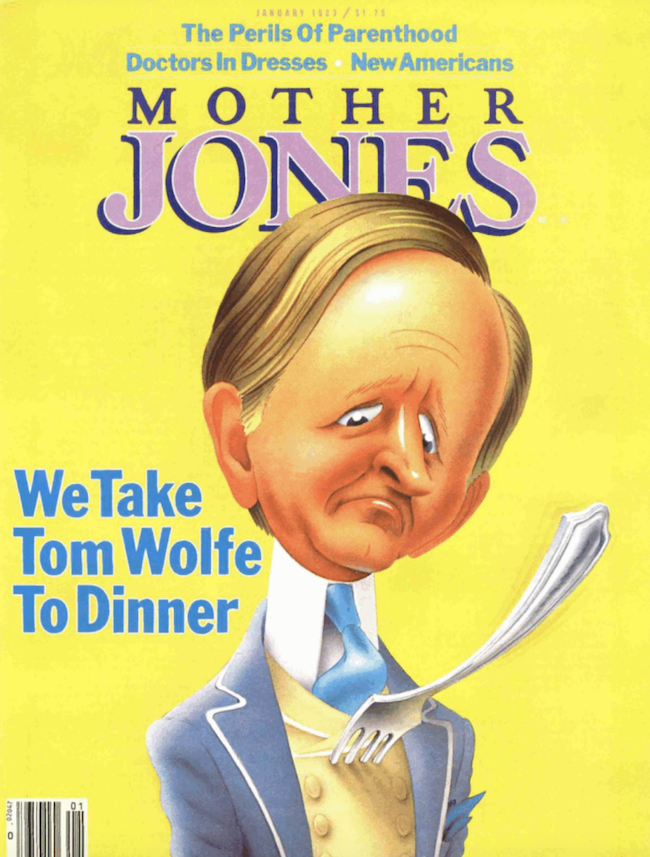

And you won’t want to miss Christopher Hitchen’s 1983 portrait of Wolfe for Mother Jones:

The American culture is a notoriously easy one to impress. Tom Wolfe has benefitted from this in two ways. First, he has done well by doing good—by pointing out the fads and absurdities, the trends and crazes that convulse the country in spasmodic and unpredictable waves. Second he has himself comes accepted as a sort of cultural authority—and if anything proves the gullibility of the American people in our time, that certainly does.

As he evolves into a fad in his own right, Wolfe makes it ever clearer what a consecrated conservative he is. There is always a reactionary growl under the tone of his writing; even at his sweetest and most amusing he usually had the time for a barb or a jeer where radicals were concerned. But as the dust settles over the ’60s and the ’70s, and as it begins to look as if we are in for a long winter of the Right, Wolfe has come out in even bolder colors.

No easy task profiling Wolfe, just ask David Kamp, who was up for the task 20 years ago in this stellar profile for Vanity Fair (and oh, by the way, Michael Lewis also wrote a fine piece on Wolfe for VF as well). This week, Kamp recalled:

For one thing, I was flat-out daunted: this was Tom Wolfe, the polymathic New Journalism pioneer, reporter, essayist, novelist, critic, and clotheshorse. For another, no one understood better than he how the game of magazine profiling worked—the temporary intimacy, the unrevealed agendas—and Wolfe, a merciless pro’s pro, would surely mental-jujitsu me into compliance or self-embarrassment.

My concerns turned out to be misplaced. Wolfe was as helpful a subject as a writer could ever hope for. Precisely because he was used to being on the other side of the process, he knew what he was in for—for better and for worse. Wolfe answered every last question I had for him, whether it was about the kind of car he drove (a ’96 Buick Roadmaster wagon that he treasured for its “90-some cubic feet of space”), or a more pointed inquiry into his proclivity for recycling old material (e.g., when he re-purposed a 1980 vignette called “The Invisible Wife” as a chapter in A Man in Full—he justified this action on the grounds that one of his idols, Guy de Maupassant, had done similar things).

Wolfe gave me all the time I asked for and more, to the point where we stayed so late for dinner one night at the Carlyle that Bobby Short, the legendary cabaret singer-pianist, had finished both of his evening sets, and wandered over to our table to join us, making inquiries to Wolfe about their mutual friend, the artist Richard Merkin.

I’ll leave you with my favorite Wolfe profile, written by Lisa Grunwald for Esquire. “Tom Wolfe Aloft in the Status Sphere” (October, 1990):

American writers are supposed to ache, burn, hunger, punish, brood, and rail. Tom Wolfe watches, chuckles, cavorts, rebels, and pisses people off. Even in 1990, that is a surprising thing to find, because it seems that the American writer is still supposed to be Hemingway. The ideal remains someone not just male but macho—a sportsman, terse and rugged, who marries too much and drinks too much and ends up a graying enigma of talent, fame, and self-destruction. The fundamental myth of the American writer seems to be of a man torn between experience and reflection, action and thought, joy and misery, love and death: a man outwardly robust and inwardly fragile.

Tom Wolfe is outwardly fragile (or at least, say, slim) and inwardly robust. Married for twelve years, father of two, seemingly unacquainted with failure, vice, or crippling self-doubt, he appears to be one of the few American writers unintoxicated by despair. Wolfe has no time for wastelands, either spiritual or actual. How could he? He’s the Ice Cream Man. He wears a white suit and an amiable grin, and he stands by a truck filled with cold, cold comfort. Early on he discovered that if nobody wanted to sample his wares, he would simply open his freezer door, dish up some scoops of bold, mad badness, and fling them (flommmmp!) at his customers’ hearts. He found that as long as his aim stayed true, the crowds would begin to gather.

…Captain Ice Cream’s favorite foes have been all forms of self-importance. Self-aggrandizement—flomp! Self-reflection—flomp! Self-delusion, self-actualization, self-centeredness, self-doubt, self-pity, self-recrimination! Self, self, self! Flomp, flomp, flomp!

Of course, not everything Wolfe has written has been an attack. All three of his longer works—The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, The Right Stuff, and The Bonfire of the Vanities—are more impressive for the stories they tell than for whatever social criticism they lob over. But that doesn’t mean Wolfe’s longer works haven’t made some people crazy. It may seem sort of quaint now, but there was a time when authors and editors and critics argued passionately about the overheated, overpunctuated style and the subjective, New Journalistic reporting that Wolfe brought to its apex in Acid Test. (Even the staid, gray New York Times was sufficiently confused—or infected—to title its review “Heeeeeewack!!!”) As for The Right Stuff, it is difficult to exaggerate how truly unorthodox it was in 1979 to make flesh-and-blood heroes of military men.

And with Bonfire, it has proved equally controversial to portray blacks in the harsh light that Wolfe clearly wanted to shine on them. Most of what he has written has had a certain calculated perversity. Even when he isn’t being a scourge, he tries to remain a rebel.

Salute.

[Photo Credit: AB—Illustration by Jim McMullan c/o SVA Archives]