Of all James Bellows’s efforts to strengthen the Tribune, none was more striking than his willingness to take chances on new young writers, whom he encouraged to work in whatever style made them comfortable and who understood, as Dick Wald stated in a memo reflecting the top editors’ philosophy, that “there is no mold for a story.” The reporter’s chief obligation, wrote Wald, was to tell the truth, “and the truth often lies in the way a man said something, the pitch of his voice, the hidden meaning in his words, the speed of the circumstances”; the real story may be found in “the exact deployment of the characters in the cast” or any of a great many other details that “make up the recognizable graininess of life to the readers.” Most of all, the paper was looking for writing with “a strong mixture of the human element,” articles that were “readable stories, not news reports written to embellish a page of record.” Among the newcomers capable of such work, three were especially notable.

Gail Sheehy, a slim, red-haired, green-eyed graduate of the University of Vermont with a couple of years of experience in department-store merchandising and two more reporting on fashion in Rochester, joined Eugenia Sheppard’s staff in the summer of 1963, drawn by what she felt were the best women’s pages of any U.S. newspaper—“they danced with life, energy, and imagination.” What they did not do was address serious social problems of women. Sheppard tended to ignore or cosmeticize concerns of the young and the aged, of mothers over childbearing, of tenants driven into rent strikes to obtain minimal household amenities, of Harlem women on drugs. “People with problems were boring to her,” Sheehy recalled, while those with money and taste and power captivated her. Their parties and the whole social whirl they generated drew her in and dominated the Tribune’s women’s pages. Then one day, Gail Sheehy, midway through pregnancy, decided to make the rounds of the city’s maternity clinics to see what free services were available to impoverished expectant mothers, of whom she pretended to be one. The results stunned and saddened her, and she wrote them up. Sheppard was not overjoyed, but Bellows backed the initiative of the new reporter, and daily journalism’s most potent arbiter of fashion and the high life began to have her social consciousness raised. It was the beginning as well of Sheehy’s career as a chronicler of American living patterns and value systems and as a wise instructor in crisis management.

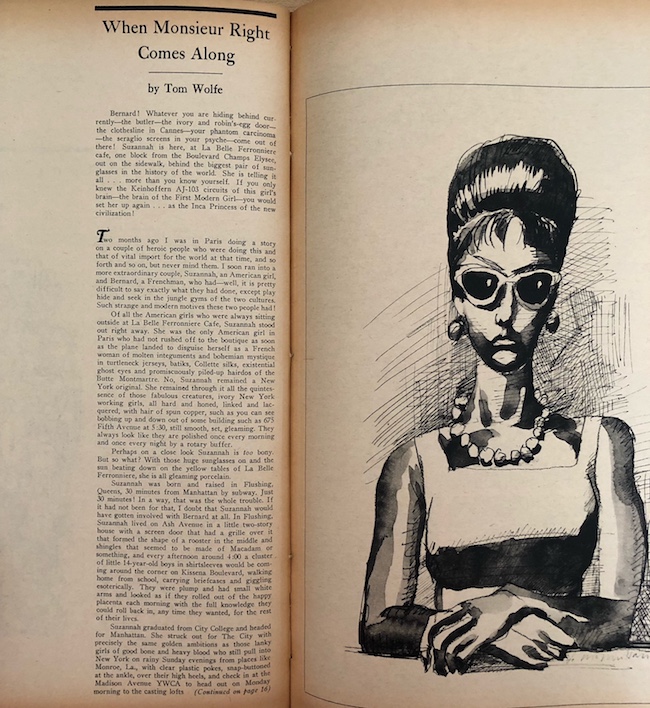

The most exotic figure among the gifted newcomers to the Tribune city room was the trim, six-foot, white-suited frame of Thomas Kennerly Wolfe, Jr., whose modish like had not been seen there since the departure of the exquisitely got-up Lucius Beebe a dozen years earlier. And no one quite so literary had performed for the paper since Bayard Taylor a century before. Wolfe was a certified intellectual with a doctorate in American studies from Yale. Besides his wardrobe and his brains, he brought a clinical eye, sardonic sensibility, omnivorous curiosity, and remarkably placid temperament to his work as he helped redefine the permissible limits of American journalism.

The son of an agronomy professor at Virginia Polytechnic Institute, Tom Wolfe was raised in Richmond and graduated from Washington and Lee. After a dreamy five-year immersion in New Haven postgraduate academia, he decided that there was too much fun and angst going on out there in the world to turn himself into a cloistered don. He served his newspapering apprenticeship at the Springfield, Massachusetts, Union and moved on to The Washington Post, where every time he turned out something fresh and original, he found himself assigned to a story on sewerage in Prince Georges County. It was not long before he presented a carefully composed scrapbook of his clippings to Buddy Weiss, who grabbed him for the Herald Tribune’s twilight time of life.

Besides his wardrobe and his brains, Wolfe brought a clinical eye, sardonic sensibility, omnivorous curiosity, and remarkably placid temperament to his work as he helped redefine the permissible limits of American journalism.

Feature writing used to mean a relaxation of traditional journalistic restraints; features usually involved good news or happy endings or odd characters—in contrast to the preponderantly grim tidings that editors defined as “news”—and reporters were invited to respond playfully. Not many had the creative knack. For Tom Wolfe, all of New York life was a single sublime feature. He did not construct his stories like anyone else. He would plunge into them in medias res, drolly painting the scene and happily twirling images to tantalize the reader before doubling back to supply comprehensibility. His stories were not so much about events as their circumstances; the real news he brought seemed to say: look, this is how people are living and behaving now. His first notable piece, about a rent strike by NYU students, ran on the split page on April 13, 1962, and began:

There have been some tough acts to follow in the field of social protest this season. We have had the sit-in, the sit-down, the hunger strike, the freedom ride, the boycott, the picket line and the marathon march.

But until yesterday in the Bronx when had Americans managed to protest with such stylish fillips as the Hypnotic Hair-Combing Co-ed, the Laugh Bandit, the All-Night Yo-Yo Contest and Great Moments from the Bard?

They’ll never go with it, Wolfe told himself. But they did; it was fun, inventive, and most decidedly not The New York Times—or any other paper. Used to the tight space requirements of the Post in Washington, Wolfe would ask how long he should make his pieces, and day city editor Dan Blum would tell him, “Until it gets boring.”

During the inactivity of the long strike, Bellows and his editors recognized Wolfe’s extraordinary gifts and resolved to put them on prominent exhibit in the paper whenever possible. And a good thing, for by then he was doing pieces for Esquire and being romanced by Newsweek, which wanted to give him a column but could not allocate enough space to accommodate his expansive prose. The week the strike ended, a Wolfe story headlined “King Hassan’s Bazaar” ran boxed across the entire top of page one—a jaunty account of a buying spree by the playboy ruler of Morocco, in Manhattan with his entourage. Bellows led with Wolfe’s romp not merely because it was interesting and fun to read on a relatively slow news day but also because it was a manifestation of a new kind of journalism, one that said that how people lived their lives was as important and meaningful to report on as the official news dispensed by governments and institutions. Wolfe’s piece was about how New York retailing worked, about how absolute monarchs lavished wealth, about taste and greed and a few other things that were at least as newsworthy as orthodox front-page fare.

Wolfe would ask how long he should make his pieces, and day city editor Dan Blum would tell him, “Until it gets boring.”

At the end of that summer, Wolfe did his last front-pager before the paper began featuring him in the finally revamped Sunday edition that first appeared in September. The story was trivial on its face, about a bunch of rich kids turned vandals at a debutante party three days earlier; the city desk caught wind of it from a passing reference in a Mirror column. Working entirely in the office, Wolfe got the deb party’s young hostess, a Wanamaker heiress named Fernanda Wetherill, on the telephone and turned out a piece of revealing social reportage. It began:

True, all the furniture was on the beach and all the sand was in the living room. And there were holes the size of Harrateen easy chairs and Philadelphia bow-front sidetables in the casement windows on the ocean side. And socially-registered rock throwers had demolished about 1,634 of a possible 1,640 panes from both directions, outside and in—making cotton broker Robert M. Harriss’ 40-room mansion at Southampton, L.I., the Ladd House, the most monumental piece of rubble in the history of American debutante party routs.

But what were 100 kids who had come skipping and screaming out of the Social Register for a deb ball weekend in the Hamptons supposed to do after the twist band packed up and went home? Hum “Wipe Out” or “Surf City” to themselves and fake it?

The scene was the story to Wolfe, and he took the reader to it instantly, and to enrich it graphically when he had no time to get out to the other end of Long Island and back, he artfully embellished.

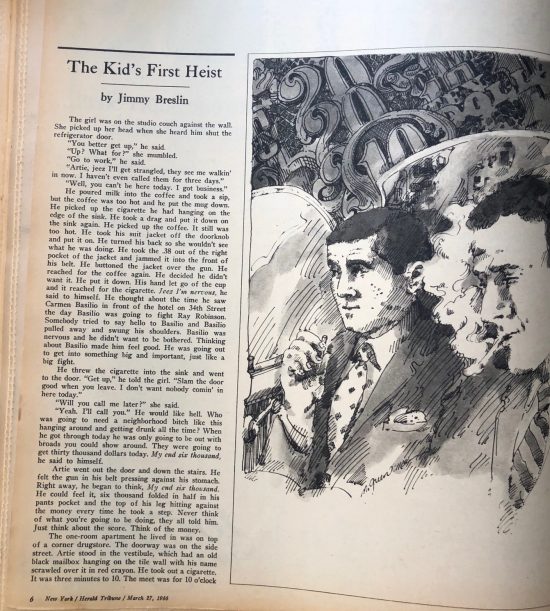

Wolfe was at his best dealing with the overprivileged; the other new man to whom Bellows gave extreme stylistic latitude—Jimmy Breslin—excelled at the opposite end of the social spectrum. Breslin’s work, while less artful than Wolfe’s, had a heavier-duty usefulness because of its elemental emotionalism, generally free of sentimentality. Both could write with wit and color, with an acute ear for speech patterns and a discerning eye for dress and furnishings and eating habits, but it was Breslin, the fat, fierce, self-absorbed swaggerer from the rough Ozone Park section of Queens, who more than any other writer on the staff came to represent the social journalism, with its intensity of feeling and poignant ironies, that the Herald Tribune was exploring at the end of its life.

Bellows had been looking for a new kind of columnist when he read a new book called Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?—a comedy of errors about the first season of the New York Mets, who happened to be owned by Jock Whitney’s sister, Joan Payson. It was written by an iconoclastic sportswriter who had worked for Long Island papers, the Boston Globe, the Scripps-Howard syndicate, and the Journal-American and was now freelancing. He had done an earlier book on the legendary horse trainer “Sunny Jim” Fitzsimmons; Whitney read both books and shared Bellows’s admiration, so they summoned the author, drank with him, laughed with him, and decided they had an authentic primitive on their hands, a rowdy noble savage. Beyond his gritty prose and high bravado, Jimmy Breslin loved New York City—all of it, especially the outer boroughs that Manhattanites scorned—with a chauvinism that prompted him once to dismiss Los Angeles as “two Newarks back to back.”

Breslin came to work at the Tribune in the middle of 1963. At thirty-three, a year older than Tom Wolfe, he stood five foot ten, weighed 240 pounds, had black hair and dark eyes and the sweet if suety face of an overaged choirboy. His office personality was that of a profane, chain-smoking, volcanic blowhard with a beer belly. Some who were close to him said this persona of an immodest Irish tough was a defense mechanism to cover a sensitive nature and genuine warmth he was too insecure to reveal except to those few he trusted. And trust did not come easily to a man whose father had abandoned the family when Jimmy was six and whose mother was a high school English teacher, an occupation that made her boy suspect in the eyes of his street peers. Taking on the protective coloration of gutter language and bold threats, Jimmy managed to survive high school and attended Long Island University over a three-year period before dropping out for good in 1950, but by then he had learned that he was better at writing than fighting. He married young and had six children, the first two twins born prematurely, so they and their mother had to spend a month in the hospital, and the Breslins were always up against it financially while Jimmy persisted in a profession in which, as he succinctly put it, “they don’t pay the fuckin’ people.” After a year on the Tribune they were paying him $20,000 plus $200 a week in expenses, which were considerable because he did not own or drive a car, took taxis everywhere, and obtained no small portion of the raw material for his column in his avocational role as a barfly. Before the decade was over, he would be earning $125,000.

He invented his own literary character, that of a populist who was now and forever on the side of debtors and deadbeats and the impoverished ignorant trapped in criminality. He wrote fondly of those who passed bum checks, who had to transport all their earthly possessions on the subway when they changed residence, who elevated shoplifting to an art form, who burned down buildings under contract, who stole petty cash from their wives. “With working people,” he wrote, “there is almost no other kind of marital trouble except money trouble.” He could mindlessly taunt a black newsboy at Bleeck’s yet turn around and produce the first authentically compassionate coverage of Harlem ever to run in the Tribune. Up there, he wrote in a memo to Bellows, they were “bewildered, uncared-about, and angry,” mired in apathy as if serving a life sentence in destitution. He wrote with special affinity for the police; he and they, or at least a lot of them, came from the same place. Most of all he was at home with his pals out at Pepe’s Bar on Astoria Boulevard in Queens, about whom he fashioned urban parables in an argot at least as authentic as any in Damon Runyon’s burlesques. In them he confronted legitimate social issues and captured a mind-set of attitudes he neither condemned nor approved: he understood and reported. His friend Mutchie’s idea of a suitable female companion, Breslin wrote, was one built like a municipal statue and just smart enough to answer the telephone.

His prose was simple, obviously indebted in its economy to Hemingway but more various in its rhythms. His sentences were generally terse and declarative, shorn of dependent clauses, but they could also run on and on, repeating words for emphasis or rhythm and gaining power with their length. It was less the richness of the language than the rightness of it for his purposes that distinguished his style, and he used it with emotional control; it could be touching without slopping into bathos—although he was not immune to that—and he could be both funny and serious at the same time, especially in writing of the underworld. “Criminals who talk too much in public,” he wrote, “usually wind up among the missing dead.”

Essentially he was a storyteller. His technique was generally to approach a story from the standpoint of the least exalted person connected with it or from, the most unexpected angle, the one no other reporter had thought of or knew how to do or had been granted the license to attempt. His usefulness to the paper was well illustrated by the work he did following the assassination of John F. Kennedy. While other reporters were concentrating on the fallen President’s assassin, theories about his involvement in a plot, and the mood in Dallas before and after the event, Breslin busied himself interviewing the surgeon who had tried to save Kennedy’s life, the priest who had administered last rites, and the funeral director who provided the best bronze casket in his stock to bear the President’s body to its eternal rest. “A Death in Emergency Room One,” the long story he filed for the Sunday paper of November 24, 1963, focused on the surgeon, thirty-four-year-old Dr. Malcolm Perry, whom Breslin pumped gently but thoroughly at a small press conference the day before during which the doctor wondered “about all the questions he asked which seemed not to bear directly on what had happened during the care of the President.” Perry’s answers to those apparently extraneous questions, of course, allowed Breslin to reconstruct the surgeon’s mental state during those horrific moments when Kennedy lay stretched before him, dying “while a huge lamp glared in his face.” Breslin’s story began:

The call bothered Malcom Perry. “Dr. Tom Shires, STAT,” the girl’s voice said over the page in the doctors’ cafeteria at Parkland Memorial Hospital. The “STAT” meant emergency. Nobody ever called Tom Shires, the hospital’s chief resident in surgery, for an emergency. And Shires, Perry’s superior, was out of town for the day. Malcolm Perry looked at the salmon croquettes on the plate in front of him. Then he put down his fork and went over to a telephone.

“This is Dr. Perry taking Dr. Shires’ page,” he said.

“President Kennedy has been shot. STAT,” the operator said.

With understated intensity and an attempt at clinical accuracy, Breslin then traced Perry’s every move during the next fifteen or so minutes and interposed the doctor’s feelings along the way, starting with: “The President, Perry thought. He’s larger than I thought he was.” Breslin took the reader virtually inside Perry’s body and brain as the surgeon “unbuttoned his dark blue glen-plaid jacket and threw it onto the floor” and did his job, always aware of “the tall, dark-haired girl in the plum dress that had her husband’s blood all over the front of the skirt” who was standing over there “tearless … with a terrible discipline” against the gray tile wall.

Then Malcolm Perry stepped up to the aluminum hospital cart and took charge of the hopeless job of trying to keep the thirty-fifth President of the United States from death. And now, the enormousness came over him.

Here is the most important man in the world, Perry thought.

The chest was not moving. And there was no apparent heartbeat inside it. The wound in the throat was small and neat. Blood was running out of it. It was running out too fast. The occipitoparietal, which is a part of the back of the head, had a huge flap. The damage a .25-caliber bullet does as it comes out of a person’s body is unbelievable. Bleeding from the head wound covered the floor.

After desperate efforts to clear Kennedy’s chest and restore his breathing and ten minutes trying to massage the still heart back to life, Perry was guided away, dimly conscious of the priest who passed him to attend to the President’s soul. Breslin then reconstructed the words that passed in privacy among the priest, the new widow, and the divinity—he managed, by economy of phrasing, not to make it read like sacrilegious voyeurism—and switched the scene to the funeral home when the Secret Service placed its urgent call for a casket befitting the head of state. At the end of his story, Breslin came back to Dr. Perry, following him as he arrived home that grim afternoon and his six-and-a-half-year-old daughter romped up to him, chattering happily and showing him her day’s schoolwork. The closing line of the piece quoted Perry as saying at the Saturday press conference, “I never saw a President before.”

One of the complaints that would arise over Breslin’s work was that he sometimes sacrificed accuracy, consciously or otherwise, to achieve emotional impact in his pieces. His story from Dallas suffered from the defect. The opening paragraphs, quoted above, contained three errors, according to Dr. Perry: Dr. Shires was the chairman of the department of surgery at the hospital, not the chief resident. Dr. Perry did not pick up the page—another doctor did, at Perry’s request. The operator did not say the words Breslin attributed to her. The sequence of Kennedy’s medical care, moreover, Breslin also got wrong, and the actual procedures followed were “misnamed… and inaccurate.” And yet, on rereading Breslin’s story long after, Dr. Perry thought that “the major focus is correct” and that the mistakes were “to be expected in such circumstances.” What he most remembered about Breslin’s work was his “concern and kindness” during the interview “and the way he looked when he said goodbye to me, and ended by saying, ‘God bless you.’ I appreciated all that very much.”

Amid the somber pomp of the funeral, Jimmy Breslin, the people’s reporter, caught the mood of bereavement by following the activities of the humblest participant connected with the ceremonies—Clifford Pollard, the khaki-overalled digger of Kennedy’s grave at Arlington Cemetery. He used a machine called a reverse hoe, not a shovel, for the job. Only Breslin would have noted that Pollard saved a little of the dirt he dug to make room for Kennedy’s coffin.

When the Herald Tribune finally got around to creating a new Sunday paper toward the end of 1963, a dozen years after the need was first perceived, it was such a departure that it lost almost as many old readers as it attracted new ones.

The new Sunday paper was Bellows’s main achievement as editor—as exciting in its way as Denson’s daring front page had been. The first step was to simplify the package. Instead of the infinite sectionalizing that had become typical of ad-fat Sunday papers, Bellows settled on four standard-sized sections: the main sheet, now incorporating the editorial page, the political columns (which were sprinkled to appear next to the news story or news feature to which each was most closely related in subject), and situation or background pieces that had formerly appeared in the news review section; the women’s section, including social news, fashions, gardening, and travel; a section combining financial and real estate news; and the sports section. To these were added a pair of staff-edited new magazines gracefully executed in rotogravure and plainly aimed at what Madison Avenue media buyers called “an upscale readership”—New York and Book Week. The syndicated supplement, This Week, targeted at a less sophisticated readership, was the only holdover from the old Sunday package; if nothing else, it added bulk and color ads.

Far more important than the arrangement of the new paper was its look. Until then, most newspaper editors’ idea of page design began and ended with the question “Where shall we put the picture?” The new Sunday Tribune was conceived as a graphic totality, rendered with the precision of superior magazine advertising design. Each page reflected what the Columbia Journalism Review, in a favorable assessment of the restyled paper, called “painstaking ‘packaging.’” Type was massed and set off by white space almost scandalously generous for newsprint pages to create what the newly hired design editor, Peter Palazzo, called “an environment of visibility.” Illustrations of unprecedented sizes, shapes, and originality, closely integrated with the text instead of mere window dressing, helped generate visual impact without sacrifice of clarity or dignity. Palazzo, a soft-spoken man with a perpetually brooding mien, set about to re-educate Bellows about what was typographically possible within the framework of a metropolitan newspaper and found the editor blessedly receptive. The collaboration worked because Palazzo, while primarily designer—trained at Cooper Union, he had worked for such high-fashion advertising accounts as I. Miller and Henri Bendel and magazines as diverse as the State Department’s overseas showcase, Amerika, and the pocket-sized Quick—was also a perceptive reader, skillful at moving beyond the literal into imagery and symbolism to render the often complex ideas behind the news. He had not been impressed with Denson’s graphic pyrotechnics, partly because, as he correctly observed, “the tone of the headlines and the style of the articles they applied to were not in consonance.” Palazzo was no hype artist.

Bellows cooperated by getting the Tribune advertising department to revamp their layouts, doing away with the old stepping-stone arrangement in which the news appeared to be mainly filler on ad-heavy pages. Every page not fully occupied by advertising was arranged so that Palazzo had at least two entire columns to work with, and on most pages the ads were squared off to permit treatment of the editorial matter. The composing room had to be retrained to Palazzo’s new ways; spacing and proportions had to be precise. Thought went into the location and length of every hairline rule. No longer were there small stories or fillers to plug holes; almost every article in the Sunday main sheet now, except for late-breaking news, was given major treatment as a spread and had to look it without violating Palazzo’s canon of visual decorum.

Staff photographers now had to give Palazzo a contact sheet instead of a single print of their own preference so the designer could decide what would work best instead of relying on the judgment of the lensmen. And the copy desk had to learn a whole new set of headline counts as Palazzo phased out the Tribune’s traditional use of Bodoni type and began using the distinctive Caslon face, with its more subtle proportioning in the weights of the thick and thin parts of the letters and stylishly drawn serifs that he thought gave the news page more character—a classic but not fussy look. For all the openness in his layouts throughout the paper, including the new magazines, Palazzo insisted on keeping the space tight between the elements within a given graphic unit and thereby achieved a kind of binding tension, a coherence of sensibility and substance. His craftsmanship would later be acknowledged throughout the field to have set the pattern for the next generations of newspaper design as photocomposition facilitated many of the techniques Palazzo and the Tribune introduced in the waning era of hot type.

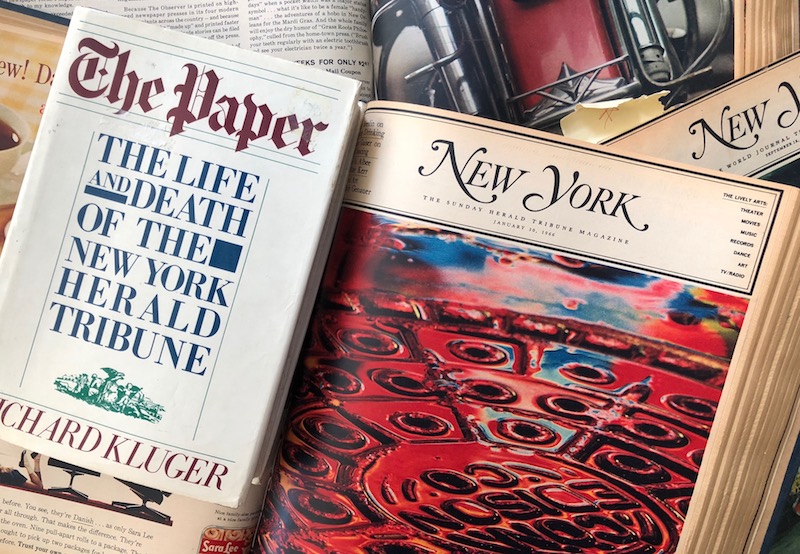

The centerpiece of the new Sunday Tribune—and one of the two offspring (the Paris edition was the other) that would outlive the parent paper—was New York. The visual freshness of the magazine was immediately apparent from its cover, devoted to a full-color panorama or detail of the cityscape that caught its raw energy or unexpected beauty. Its interior set a standard for graphics not seen before in an American newspaper magazine. The look was one of chaste and elegant understatement, achieved within a grid of three columns to a page that played off blocks of gray text, white breathing room, and dark illustration. Headlines were small, hardly more than inviting labels that left the tone-setting to the large, arresting artwork, produced by some of the leading illustrators of the day.

Appearance aside, the contents of New York warranted keeping it around for the rest of the week. Its metropolitan orientation, in intentionally sharp contrast to the Times’s Sunday magazine, sought to capture the verve and variety of city life in stylish prose that could not be mistaken for the solid Times style or the cheap, inflated puffery of the Daily News’s Sunday supplement. Although most of the articles in New York were by outsiders, the core of the magazine during its early stages was the work of the paper’s prolific new stars—Tom Wolfe, his antennae tuned to the latest from the city’s salons, galleries, fashionable boulevards, and expensive playgrounds, and Jimmy Breslin on the town’s grubbier precincts and stalwarts.

Thus, that first autumn, while Wolfe was writing in New York on why Park Avenue doormen hated Volkswagens, how to go celebrity-watching on Madison Avenue Saturday afternoons, the joys of stock-car racing out at Riverhead on eastern Long Island, and what qualified as le style supermarket for the chic Manhattan matron, Breslin was covering conditions on skid row, in alimony jail, and along Long Island’s public beaches, inventorying New York street action at two in the morning, and lamenting the imminent suburbanization of Staten Island, the city’s outermost borough. These were supplemented by pieces from local name writers—such as Langston Hughes on gospel singing in Harlem, Martin Mayer on why New York’s public schools were so badly administered, Nat Hentoff on the time-wasting of the jury system, Liz Smith on people-watching at discotheques, and “Pogo” creator Walt Kelly in words and pictures on Greenwich Village types.

But for the most part it was not the prominence of the bylines but the subject and treatment of the articles that made them attractive, e.g., the economics of the taxi industry, literacy tests from the Puerto Rican perspective, the fiery personality of transit workers’ boss Mike Quill, how the Music Corporation of America was gearing itself to the computer age, why comic books were so violent, the adventures of a cop who moonlighted at midwifery, the agony and the ecstasy of Orson Welles. Each week’s lineup was as varied and unpredictable as the city itself. Following the general-interest articles came the Tribune’s cultural critics, each given a separate page or more, whose individual appeal—the authority of Walter Kerr on theater, the candor of Judith Crist on the movies, the graceful evocations of Emily Genauer on art, the passion of Walter Terry on the dance, the brightness of new young music critic Alan Rich—seemed to gain in stature and liveliness from being grouped. Behind them New York offered a highly readable guide to the city’s coming cultural events and most notable entertainment, television listings for the following week, bridge and chess columns, puzzles, and the paper’s four best comic strips.

Orchestrating this snappy weekly performance was Sheldon Zalaznick, formerly senior editor at Forbes magazine, a smart, compulsively neat man of thirty-five. A working pencil editor, solid in judging the pace and structure of a magazine story—a different species from the kind most Tribune editors were used to dealing with—Zalaznick was the beneficiary from the start of the brainstorming services of Clay Felker, his opposite in temperament and work habits and detectably more ambitious. It was Felker with whom New York would shortly become identified as Zalaznick stepped up to editor of the whole Sunday paper in 1964.

“New York is designed for work and accomplishment, not for ease of living,” Clay Felker once wrote. “This city has almost no use for anyone who isn’t working and producing well. It’s a city for people at their peak…. You’ve got to be the best to survive in New York.”

Felker, a rapid-fire talker as intense as he was inconstant in his enthusiasms, with an eclectic intellect adept at making connections between ideas and their manifestations, at thirty-eight had recently lost out in a struggle to become the top editor of Esquire, where he had been feature editor after working on the New York Star, Life, and Sports Illustrated. At the time Bellows hired him as a consultant for the new Sunday paper, he was also consulting for the Viking Press and British television personality David Frost and helping manage the film career of his wife, actress Pamela Tiffin. All this well-wired linkage to the world of entertainment and communications made him a uniquely useful idea man. A native of St. Louis, where his father was editor of The Sporting News, the definitive journal of organized baseball, Felker graduated from Duke and on his arrival in New York was infected with a Fitzgeraldian fascination for the big city’s ephemeral glamour, shifting power bases, and the pecking order of its numerous subcultures. As an editor, he was remarkably good at conceptualizing stories and then putting the idea together with a writer who could fashion it well and on time. He was thought to go off the deep end, sparks flying, with some of his ideas, but that hypercreativity was what made him such a valuable resource—if one was selective in gauging his offerings. Felker’s problem on joining the Tribune was that he was used to dealing with top-flight freelance writers, and when he dreamed up story ideas for the new Sunday Tribune, most often in the areas of politics and sports, and suggested outside people to execute them, he frequently appeared to be usurping the prerogatives of the paper’s editors and writers.

“I was poaching on their territory and not doing it very diplomatically,” he recalled. Zalaznick, also a magazine man by training, was sympathetic with Felker’s problem even as he recognized his gifts. “Clay frightened people,” Zalaznick recounted. “He was high-powered, aggressive, and smart as hell. He made second-rate people nervous—and whatever veneer he had wore thin pretty fast.”

Soon Felker’s services to the Tribune were assigned to Zalaznick exclusively, and he used them to complement what he regarded as his own narrower frame of reference. Felker’s instincts scouted out who and what was about to be fashionable—“whether it was that the neckline of women’s dresses would soon be descending to the nipple,” Zalaznick noted, “or that pro football was soon to replace church on Sunday.”

After years of neglect, the Sunday edition of the Tribune as redesigned by James Bellows, Peter Palazzo, and Sheldon Zalaznick rapidly attracted so much attention among New York sophisticates that by 1965 the advertising director, Robert Lambert, was gladly seizing on it to project the paper’s overall image. Its glossiest, most arresting feature, New York magazine, was beginning to win color advertising from department stores and garment manufacturers of the kind that had run exclusively for so long in the Times Sunday magazine. With such a promotable vehicle at hand, Lambert campaigned hard on Madison Avenue, arguing that New York was a “top-oriented town” and the Tribune readership led the way in education, buying power, and influence.

The freshness and excitement so apparent in New York magazine were organically related to the personality of its decidedly top-oriented editor. Clay Felker seemed perpetually overstimulated by the city. “New York is designed for work and accomplishment, not for ease of living,” he once wrote. “This city has almost no use for anyone who isn’t working and producing well. It’s a city for people at their peak…. You’ve got to be the best to survive in New York.” People at their peak had a magical lure for Clay Felker. Rarely at ease, his speech a staccato of Midwestern nasality, his mind a buzz saw reducing forests to workable two-by-fours, he practiced a tax-deductible lifestyle—his East Side duplex with its antique collection, his parties with the celebrated as a drawing card, the rented limousine and summer place in the fashionable Hamptons—so that people would regard him as a success before he had become much of one. He was an emotional man, one who screamed out his frustrations at the office and could not mask his boredom with people who had no information or talent that might somehow be useful to him. His enthusiasm and intensity, like John Denson’s, were contagious, but he was a better-educated man with a much broader-ranging mind and made no secret of the fact that his life was one sustained scouting expedition whereas Denson stole other people’s ideas, usually without crediting them. Writers loved Felker or hated him, sometimes both simultaneously. He was on the paper only for its final two and a half years, but Clay Felker, like Denson, must be counted on the short roster of inspired editors of the Tribune because he helped reshape New York journalism and redefined what was news.

The understated format of New York allowed him to carry a wide range of subject matter and stylistic treatments without risk of discord. Thus, Felker could include both the instructive narratives of onetime Tribune reporter George Jerome Waldo Goodman, under the pen name of “Adam Smith,” employing the patois of a Wall Street hipster to demythicize the high-rolling gambitry of the money game, and the subdued but equally informative prose of NYU professor Peter Drucker on the latest models of corporate man. Likewise he varied the contents geographically, ethnically, occupationally, and culturally while sticking to a Greater New York frame of reference. One week New York might deal with “the New Bohemia” of the East Village or whether commercial success would spoil the offhand personality of The Village Voice; the next week, it would be the perils of pampered adolescence in Fairfield County or how Helen Gurley Brown ran Cosmopolitan.

“Style can’t carry a story if you haven’t done the reporting,” said Tom Wolfe. “If you’re writing non-fiction that you want to read as well as fiction, you’ve got to have all those details—you can’t make it up.”

The hallmark of the magazine during its life as a Tribune Sunday supplement was the work for it by Tom Wolfe, who thrived on the stylistic freedom granted him by Felker. Together, they attacked what each regarded as the greatest untold and uncovered story of the age: the vanities, extravagances, pretensions, and artifice of America two decades after World War II, the wealthiest society the world had ever known.

The first full flowering of Wolfe’s technique in exploring this subject matter under Felker’s tutelage was “The Girl of the Year” in the December 6, 1964, issue of New York. Each year the fashion press seemed to seize on a young, attractive New York woman of at least nominal social standing, investing her with the glamour of a show business star by way of convincing readers that real people wore designer clothes. The distinction that year was held by twenty-four-year-old “Baby Jane” Holzer, a child of wealth married to a young real estate mogul with a Princeton degree and living in a large Park Avenue apartment with expensive landscapes on the walls. A sometime model and actress in underground movies, Jane Holzer and her world could not have been brought vividly to life under the strictures of traditional journalism, which required the writer to adopt what Wolfe called a “calm, cultivated and in fact genteel voice” with “a pale-beige tone” of understatement that he felt had begun to pall by the Sixties.

Conventional journalism, Wolfe would argue later, had become “retrograde, lazy, slipshod, superficial, and, above all, incomplete—should I say blind?—in its coverage of American life.” To render it adequately, he developed a scenic technique that was the essence of what would shortly become known as the New Journalism: “The idea was to give the full objective description, plus something that readers had always had to go to novels and short stories for: namely, the subjective or emotional life of the characters.” To convey this, Wolfe invented a prose style of utter distinctiveness, shifting restlessly back and forth in time and place to gather dimension and perspective as he traveled, absorbing images in multicolored flashes, dialogue in all its often inarticulate inanity, and a surfeit of physical particulars that were both vivifying and inferentially judgmental. His writing indulged in every device the language offered—gratuitous capitalization, insistent italics, dashes and ellipses like traffic signals on the freeway of his thoughts, a picket fence of exclamation points, repetition for emphasis, sometimes no punctuation at all, extended similes, leaping metaphors, somersaulting appositives, mock-heroic invocations, arch interjections, rocketing hyperbole, antic onomatopoeia. Thus, Wolfe opened his portrait of Jane Holzer by peering out of her eye sockets upon the scene of a Rolling Stones concert:

Bangs manes bouffants beehive Beatle caps butter faces brush-on lashes decal eyes puffy sweaters French thrust bras flailing leather blue jeans stretch pants stretch jeans honey dew bottoms eclair shanks elfboots ballerinas Knight slippers, hundreds of them these flaming little buds, bobbing and screaming, rocketing around inside the Academy of Music Theater underneath that vast old mouldering cherub dome up there—aren’t they super-marvelous!

“Aren’t they super-marvelous!” says Baby Jane, and then: “Hi, Isabel! You want to sit backstage—with the Stones?”

Then Wolfe moved back and placed his subject in the scene:

Girls are reeling this way and that way in the aisle and through their huge black decal eyes, sagging with Tiger Tongue Lick Me eyelashes and black appliqués, sagging like display window Christmas trees, they keep staring at—her—Baby Jane—on the aisle. What the hell is this? She is gorgeous in the most outrageous way. Her hair rises up from her head in a huge hairy corona, a huge tan mane around a narrow face and two eyes opened—swock!—like umbrellas, with all that hair flowing down over a coat made of … zebra! Those motherless stripes! Oh, damn! Here she is with her friends, looking like some kind of queen bee for all flaming little buds everywhere. She twists around to shout to one of her friends and that incredible mane swings around on her shoulders, over the zebra coat.

“Isabel!” says Baby Jane, “Isabel, hi! I just saw the Stones! They look super-divine!”

“The Girl of the Year” was not a story at all by any conventional journalistic standard; it was a reportorial collage, the artfully flung debris of a social condition, projected through a lens that distorted by design. Objectivity need not apply. But it was fact upon which Tom Wolfe built his effects. “Style can’t carry a story if you haven’t done the reporting,” he said. “If you’re writing non-fiction that you want to read as well as fiction, you’ve got to have all those details—you can’t make it up.”

Once at least, when he had not obtained enough details and instead relied on hearsay, indulgent style, and tendentiousness to carry off his performance, Wolfe dishonored himself and the Tribune. He and Felker had decided that The New Yorker had a grossly inflated reputation and was regarded by all but derrière-garde literati as moribund and pretentious; Wolfe would take the magazine—and its august and reclusive editor, William Shawn—down a few pegs in his withering fashion.

Wolfe called Shawn for an interview and was turned down, and everyone else there he tried also refused him, though Shawn later denied Wolfe’s claim that the editor had directed his staff to do so. So Wolfe scraped and scrounged for information from former staff members and contributors—no easy trick since the magazine seemed to grant lifetime tenure to its employees and paid its writers the highest rates in Christendom—and anywhere else he could find it, and delivered a two-part, 11,000-word snort intended to be a dose of The New Yorker’s own medicine and a disrobing of Shawn. Appearing in New York on April 11, 1965, the first part was titled “Tiny Mummies! The True Story of the Ruler of 43rd Street’s Land of the Walking Dead!” Shawn obtained a copy before publication, accused Wolfe and the Tribune of character assassination, and appealed to Whitney to suppress it.

If he had stuck to literary criticism, Wolfe would have been on defensible ground. In deriding The New Yorker as “the most successful suburban women’s magazine in the country” and dismissing it for “a strikingly low level of literary achievement” that, save for the contributions of Mary McCarthy, J.D. Salinger, John O’Hara, and John Updike, had taken it “practically out of literary competition altogether” for the past fifteen years, he might have mustered some agreement. The New Yorker’s non-fiction did seem to specialize in great, long, limp, meticulously punctuated but unreadable sentences with multiple dependent clauses—“Lost in the Whichy Thicket,” Wolfe titled the second article by way of spoofing the magazine’s prevailing style. And it was not outlandishly beyond the realm of fair critical comment to suggest that The New Yorker’s real value and purpose was what Wolfe characterized as “a national shopping news” with its articles providing “the thin connective tissue” between all the ads for fancy things and ritzy places.

When he went on, however, to mock the fustiness of the magazine’s physical surroundings, customs, editorial procedures, and chief editor, Wolfe lacked both factual ammunition and targets worth demolishing. He wrote of how James Thurber’s office was maintained as a shrine, of a steady blizzard of multicolored interoffice memos on “rag-fiber” paper of the highest quality, of elaborate editing machinery in which copy went in one end and was eventually extruded in a form often unrecognizable to and unapproved by the author. He pictured the hallways as filled with aged messengers bearing those countless colored memos on paper of the best quality, “caroming off each other—bonk old bison heads … transporting these thousands of messages with their kindly old elder bison shuffles shoop-shooping along.” But he reserved the full strength of his mockery for Shawn, “the Colorfully Shy Man,” whom he portrayed as neurotically diffident, excessively polite, soft-spoken with spastic little pauses between words, draped in layers of sweaters as he went pat-pat-patting through the halls—“The Smiling Embalmer” who ruled with an iron hand over “The Whisper Zone.” Shawn’s alleged paranoid behavior Wolfe tied by strong intimation to “the story” that it was he rather than Bobby Franks, a fellow pupil at his Chicago private grammar school, who had been the intended victim of the notorious Loeb-Leopold thrill murder. Finally, he reported that Shawn in his shyness failed to attend his magazine’s gala fortieth birthday party at the St. Regis Hotel; Wolfe imagined him instead staying home alone with his collection of beloved jazz records and songs of a better, bygone age, listening to the classic version of “I Can’t Get Started,” which Wolfe attributed to Bix Beiderbecke.

But it was not Bix Beiderbecke who recorded “the real ‘I Can’t Get Started,’” it was Bunny Berigan—a standard known to most music buffs. James Thurber’s old office was not set aside as a shrine but was in regular use. The interoffice memos were on ordinary paper and not systematically colored (and what was funny about old men serving out their years as messengers?). And writers for The New Yorker were shown the edited version of their prose and their approval was required. There was no persuasive documentation linking Shawn to the Loeb-Leopold case other than his having attended the same school as the murdered boy. And there were too many other un-facts and wrong details that could not be waved away as literary license. The essence of the charge against Shawn that prompted this elaborate needling was that he was a shy man who ran a dull magazine. The whole business added up to a case of confected overkill. But Whitney would not suppress it and it raised a storm.

E. B. White wrote Whitney that Wolfe’s “violated piece every rule of conduct I know anything about. It is sly, cruel, and to a large extent undocumented, and it has, I think, shocked everyone who knows what sort of person Shawn really is. I can’t imagine why you published it—the virtuosity of the writer makes it all the more contemptible….” The really reclusive J.D. Salinger wired that Wolfe’s “sub-collegiate and gleeful and unrelievedly poisonous article” was so terrible that Whitney’s name “will very likely never again stand for anything either respect-worthy or honorable.” Richard Rovere, who had written for The New Yorker for twenty-one years, added, “In no important respect is the place I have known the one described by Tom Wolfe.” New York Post columnist Murray Kempton called Wolfe “a ballet dancer whose chief satisfaction from the life of art is the chance it gives to wear spangles.”

The uproar appalled Jock Whitney, who knew many of the complainants personally and found Wolfe’s pieces gratuitously abusive, done for the sport of it, and overstepping the bounds of propriety—“and propriety was very important to him,” recalled Ray Price, Whitney’s Tribune confidant. But the louder Wolfe’s denouncers wailed, the less Whitney was inclined to confess culpability in public. Price’s counsel to him was persuasive: “We have every right to dissect The New Yorker, and to do it irreverently, even zestfully, which Tom did….The pieces were cruel. They were not malicious….Maybe everybody’s so protective of Shawn because he needs protection; but dammit all, he is a public figure and his magazine does dish it out, sometimes with a cruel hand. The crybabies ought to be able to take it, too….Maybe they thought they were, or should be, immune.…” In the end, Wolfe went unreprimanded, although his editors got a dressing-down from Bellows, and while they would ever after regret the factual errors and distortions, Wolfe and Felker believed the lampoon had captured the figurative truth and accurately lanced the magazine’s bloated reputation.

The notoriety of his send-up of The New Yorker had the effect unintended by Wolfe’s detractors of greatly enhancing his fame. A thoughtful critique by Dwight Macdonald in The New York Review of Books animadverted on the Wolfe technique, calling it “parajournalism … a bastard form, having it both ways, exploiting the factual authority of journalism and the atmospheric license of fiction.” Less hostile was Leonard Lewin, himself a gifted social satirist, who examined the Wolfe–New Yorker affair in the Columbia Journalism Review, noted that in his more successful efforts Wolfe achieved “an intimacy and a sense of participation rarely possible in conventional non-fiction,” but concluded: “‘Fact’ and ‘fiction,’ like ‘news’ and ‘opinion,’ must be distinguishable, however interwoven and however great an effort it requires from the reader or the writer. Even when it spoils the fun; it’s one of the entrance requirements of the trade.”

With Wolfe as its prime attraction, Felker’s magazine won increasing attention and admiration. Writing in Saturday Review early in 1966 on the proliferation of homegrown Sunday newspaper supplements, John Tebbel said, “Far in the lead is the New York Herald Tribune’s New York magazine, whose editor, Clay Felker, is turning out a brilliant, sophisticated product that has broken entirely new ground.” Both the magazine and the rest of the Sunday paper, Tebbel feared, might be too far ahead of their time to succeed commercially. He was right. Yet looking back nearly two decades later, New York Times publisher Punch Sulzberger remarked, in conceding that his paper had been at least somewhat influenced by the Tribune’s stress on lifestyle reportage, “I thought that Clay Felker in particular made an impact on American journalism by what he did with that magazine.”

Excerpted from The Paper: The Life and Death of the New York Herald Tribune.