I met Kerouac only twice, both for brief periods of not more than 15 minutes, and communication between us was abrupt and unreal. What I wrote about the man and writer was the result of feeling, experience and legwork, not friendship. The hippies-Yippies have replaced the beats today, but they are the logical and expanded second wave; when their history is written it will all point back unerringly to the homemade anarchistic breakthrough of the Beat Generation—the dropouts, communes, drugs, beards, hair, handcrafts, meditation, etc. I owe my own turn-on as a writer who had been coldshouldered by my quasi-academic peers of the Cerebral Generation to the revivifying power of the beats and I can testify in court if need be to the actuality of the beat messianic excitement. Behind it, in my judgment, was the principal catalytic figure of Kerouac; today Ginsberg and Burroughs get a much bigger and better press and are highly respected by the university intellectuals whereas Kerouac is regarded very fishily as a simpleminded athletic type run amok. It might even be that his final value will have been primarily inspirational: but if this is so, it was extensive beyond current awareness and I am enormously glad that I sweated my way through this overlong and slightly obsessive piece, even incurring Kerouac’s oblique anger (via letter) at the less flattering questions I raised about the future of his work.

Both of us were in a touchy situation because my article served as the introduction to Desolation Angels (1965) when his reputation in New York was charred and uncertain after mere vogue-followers had deserted for yet a new substitute penis in the search for thrills. Jan Cremer, post-beat, pre-Provo, cockeyed kid and terrifyingly cool manipulator of his own destiny, stands astride the two very separate possibilities of pop celebrity and uniquely independent writer-painter. He would like to be a fantasy figure, “a world idol” as he puts it looking you right in the eye without a smile, a rough combination of Bobby Kennedy and Yevtushenko and Cassius Clay (as he told me in 1966—see how quickly his images have become ghosts!); his idea of selfdivinity can drive you crazy; and yet I admire both his unusual poise and his courage but have no certainty about which direction he will take. My hunch is that he will be determined by circumstances and therefore become an avantgarde showbusiness symptom of his time rather than the disturbing prophet I truly feel in him. It is almost an arrow pointing the way our times have changed that my own involvements, and those of our shattered American world, have developed in the last decade from Jack Kerouac (who returned to womblike Lowell, Massachusetts, and shucked off every relationship with his own Beat Generation) to Eldridge Cleaver and Abbie Hoffman. Jan Cremer fascinates me because he made a unique individual play out of what would later become hippie materials, cashing in on the style of the young culture outlaws who are now a new world-class, but Cleaver and Hoffman have each in their own way joined the Youth Revolution to socialist-anarchist motors that have taken them into the crumbling center of America. They are leaders—a powerful word on the New Left these days—and young men and women stand behind their words with action. Beats, Provos, Black Panthers, Yippies: what strange names for literature but then what else is literature right now but the eruption of the outraged spirit in language? Dig it while I give and take with these men who project to me more than themselves, who summon up a new quality of experience that grips me and causes me to work out on the most basic level of my own life.

All of us with nerve have played God on occasion, but when was the last time you created a generation? Two weeks ago maybe? Or instead did you just rush to your psychiatrist and plead with him to cool you down because you were scared of thinking such fantastic-sick-delusory-taboo-grandiose thoughts? The latter seems more reasonable if less glamorous; I’ve chickened out the same way.

But Jack Kerouac singlehandedly created the Beat Generation. Although Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and William Burroughs brought their separate and cumulative “madness” to the yeasty phenomenon of the BG (and you will find them in Desolation Angels under the names of Irwin Garden, Raphael Urso and Bull Hubbard), it was Kerouac who was the Unifying Principle by virtue of a unique combination of elements. A little boy tucked into the frame of a resourceful and independent man, a scholarly Christian-mystic-Buddhist who dug Charlie Parker and Miles Davis and ice-cream, a sentimental, apolitical American smalltowner who nevertheless meditated on the universe itself like Thoreau before him, Jack Kerouac threw a loop over an area of experience that had previously been disunited and gave it meaning and continuity. The significant thing about Kerouac’s creation of the Beat Generation, what made it valid and spontaneous enough to leave a lasting wrinkle on history and memorialize his name, was that there was nothing calculated or phony about the triumph of his style. He and his friends in the mid to late 50s, before and while the beat flame was at its hottest, were merely living harder and more extensively than any of their articulate American counterparts. One of the minor characters in Angels, an Asian Studies teacher out on the Coast, says at an outdoor party that the core of Buddhism is simply “knowing as many different people as you can,” and certainly this distinguished Kerouac and his boys with a bang.

They zoomed around this and other countries (San Francisco, Mexico City, Tangier, Paris, London, back to New York, out to Denver, yeah!) with a speed, spirit and fierce enthusiasm “to dig everything” that ridiculed the self-protective ploys engaged in by the majority of young American writers at the time. This is not to say that Kerouac, Ginsberg, Corso and Burroughs didn’t have individual equals and perhaps even superiors among their homegrown literary brothers; men like Salinger, Robert Lowell, Mailer, Joseph Heller, James Jones, Styron, Baldwin, etc., were beholden to no one in their ambition and thrust of individual points of view, but that is exactly what each remained—individual. The beats, on the other hand, and Jack Kerouac in particular, evolved a community among themselves that included and respected individual rocketry but nevertheless tried to orchestrate it with the needs of a group; the group or the gang, like society in miniature, was at least as important as its most glittering stars—in fact you might say it was a constellation of stars who swung in the same orbit and gave mutual light—and this differentiated the beat invasion of our literature from the work of unrelated individuals conducting solo flights that had little in common.

As an Outsider, then, French Canadian, Catholic, but with the features and build of an all-American prototype growing up in a solid New England manufacturing town, much of Kerouac’s early life seems to have gone into fantasy and daydreams which he acted out.

It can be argued that the practice of art is a crucial individual effort reserved for adults and that the beats brought a streetgang cop-fear and incestuousness into their magazines, poetry and prose that barred the door against reality and turned craft into an orgy of self-justification. As time recedes from the high point of the Beat Generation spree, roughly 1957–1961, such a perspectivelike approach seems fairly sane and reasonable; from our present distance much of the beat racket and messianic activity can look like a psychotics’ picnic spiked with bombersized dexies. Now that the BG has broken up—and it has become dispersed less than 10 years after its truly spontaneous eruption, with its members for the most part going their separate existential ways—a lot of the dizzy excitement of the earlier period (recorded in Desolation Angels and in most of Kerouac’s novels since On the Road) can be seen as exaggerated, hysterical, foolish and held together with a postadolescent red ribbon that will cause some of its early apostles to giggle with embarrassment as the rugged road of age and arthritis overtakes them.

But there was much more to the beats, and to Kerouac himself, than a list of excesses, “worship of primitivism” (a sniffy phrase introduced by the critic Norman Podhoretz), crazy lurches from North Beach to the Village, a go-go-go jazzedup movie that when viewed with moral self-righteousness can seem like a cute little benzedream of anarchy come true. This more or less cliched picture, especially when contrasted with the “Dare I eat a peach?” self-consciousness practiced in both the universities and the influential big-little magazines like the Partisan and Kenyon Reviews, was however a real part of a beat insurrection; they were in revolt against a prevailing cerebral-formalist temper that had shut them out of literary existence, as it had hundreds of other young writers in the America of the late ’40s and ’50s, and the ton of experience and imagery that had been suppressed by the critical policemen of post-Eliot U.S. letters came to the surface like a toilet explosion. The first joy of the beat writers when they made their assault was to prance on the tits of the forbidden, shout the “antirational”—what a dreary amount of rational Thou Shalt Nots had been forced down their brains like castor oil—exult in the antimetrical, rejoice in the incantatory, act out every bastard shape and form that testified to an Imagination which had been imprisoned by graduate-school wardens who laid down the laws for A Significant Mid-Twentieth-Century American Literature.

One should therefore first regard the insane playfulness, deliberate infantilism, nutty haikus, naked stripteases, free-form chants and literary war dances of the beats as a tremendous lift of conscience, a much-needed release from an authoritarian inhibiting-and-punishing intellectual climate that had succeeded in intimidating honest American writing. But the writer’s need to blurt his soul is ultimately the most determined of all and will only tolerate interference to a moderate point; when the critic-teachers presume to become lawgivers they ultimately lose their power by trying to take away the manhood (or womanhood) of others. By reason of personality, a large and open mind, a deceptively obsessive literary background coupled with the romantic American good looks of a movie swinger, Jack Kerouac became the image and catalyst of this Freedom Movement and set in motion a genuinely new style that pierced to the motorcycle seat of his contemporaries’ feelings because it expressed mutual experience that had been hushed up or considered improper for literature. The birth of a style is always a fascinating occasion because it represents a radical shift in outlook and values; even if time proves that Kerouac’s style is too slight to withstand the successive grandslams of fashion that lie in wait, and if he should go down in the record books as primarily a pep pill rather than an accomplished master of his own experience (and we will examine these alternatives as we dig deeper into his work), it is shortsighted of anyone concerned with our time in America to minimize what Kerouac churned into light and put on flying wheels.

This last image is not inappropriate to his America and ours, inasmuch as he mythicized coast-to-coast restlessness in a zooming car in On the Road (1957) at the same time that he took our customary prose by its tail and whipped it as close to pure action as our jazzmen and painters were doing with their artforms. But Kerouac did even more than this: now in 1965, almost a decade after Road, we can see that he was probably the first important American novelist (along with Salinger) to create a true pop art as well. The roots of any innovator nourish themselves at deep, primary sources, and if we give a concentrated look at Kerouac’s, the nature of his formative experience and the scope of his concern might surprise a number of prejudiced minds and awaken them to tardy recognition.

John (Jack) Kerouac, as every reader-participant of his work knows, was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1922, a very much American kid but with a difference: he was of French-Canadian descent and the family (his father was a printer, interestingly enough) embraced the particularly parochial brand of Catholicism which observers have noted about that northern outpost of the Church. As far as WASP America went, Kerouac was almost as much of an Outsider as the radical-Jewish-homosexual Allen Ginsberg, the urchin-reform-school-Italian Gregory Corso and the junkie-homosexual-disgrace-of-a-good-family William Burroughs that he was later to team up with.

From his earliest years, apparently—and laced all through Kerouac’s work—one sees an extreme tenderness toward animals, children, growing things, a kind of contemporary St. Francisism which occasionally becomes annoyingly gushy to dryer tastes; the sympathetic reader credits Kerouac with having genuine “saintly” forbearance as a human but also winces because of the religious-calendar prettiness in a work like Visions of Gerard (1963), the sincere and perhaps overly idealized elegy to a frail older brother who died during the writer’s childhood. If Kerouac’s feeling occasionally floods into a River of Tears it is nevertheless always present, buckets of it, and one is finally astonished by the enormous responsiveness of the man to seemingly everything that has ever happened to him—literally from birth to a minute ago.

I can remember the word being passed around in New York in the late 40s that “another Thomas Wolfe, a roaring boy named Kerouac, ever hear of him?” was loose on the scene.

As an Outsider, then, French Canadian, Catholic (“I am a Canuck, I could not speak English till I was 5 or 6, at 16 I spoke with a halting accent and was a big blue baby in school though varsity basketball later and if not for that no one would have noticed I could cope in any way with the world and would have been put in the madhouse for some kind of inadequacy…”), but with the features and build of an all-American prototype growing up in a solid New England manufacturing town, much of Kerouac’s early life seems to have gone into fantasy and daydreams which he acted out. (“At the age of 11 I wrote whole little novels in nickel notebooks, also magazines in imitation of Liberty Magazine and kept extensive horse racing newspapers going.”) He invented complicated games for himself, using the Outsider’s solitude to create a world—many worlds, actually—modeled on the “real” one but extending it far beyond the dull-normal capacities of the other Lowell boys his own age. Games, daydreams, dreams themselves—his Book of Dreams (1961) is unique in our generation’s written expression—fantasies and imaginative speculations are rife throughout all of Kerouac’s grownup works; and the references all hearken back to his Lowell boyhood, to the characteristically American small-city details (Lowell had a population of 100,000 or less during Kerouac’s childhood), and to what we can unblushingly call the American Idea, which the young Jack cultivated as only a yearning and physically vigorous dreamer can.

That is, as a Stranger, a first-generation American who couldn’t speak the tongue until he was in knee pants, the history and raw beauty of the U.S. legend was more crucially important to his imagination than it was to the comparatively well-adjusted runnynoses who took their cokes and movies for granted and fatly basked in the taken-for-granted American customs and consumer goods that young Kerouac made into interior theatricals. It is impossible to forget that behind the 43-year-old Kerouac of today lies a wild total involvement in this country’s folkways, history, small talk, visual delights, music and literature—especially the latter; Twain, Emily Dickinson, Melville, Sherwood Anderson, Whitman, Emerson, Hemingway, Saroyan, Thomas Wolfe, they were all gobbled up or at least tasted by him before his teens were over (along with a biography of Jack London that made him want to be an “adventurer”); he identified with his newfound literary fathers and grandfathers and apparently read omnivorously. As you’ll see, this kind of immersion in the literature of his kinsmen—plunged into with the grateful passion that only the children of immigrants understand—was a necessity before he broke loose stylistically; he had to have sure knowledge and control of his medium after a long apprenticeship in order to chuck so much extraneous tradition in the basket when he finally found his own voice and risked its total rhythm and sound.

Around Kerouac’s 17th year, we find him attending the somewhat posh Horace Mann School in upper Manhattan—the family had now moved to the Greater New York area with the onset of his father’s fatal illness—and racking up a brilliant 92 point average. (His brightness by any standard confounds the careless “anti-intellectual” charges leveled at him by earnest Ethical Culture types.) Then in 1940 he entered Columbia University on a scholarship. Kerouac, so far as l know, never actually played varsity football for Columbia although he was on the squad until he broke his leg, and had been a flashy Gary Grayson-type halfback while at Horace Mann. He also never finished college, for World War II exploded after he had been there approximately two years; but during this period he did meet two important buddies and influences, William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, and it is interesting to keep in mind that the titles of both works which brought these men to public attention, Naked Lunch and Howl respectively, were coined by Kerouac, the verbal sorcerer. Burroughs was a spare, elegant, fiercely authentic junkie and occasional dilettante dabbler in crime, such as a holdup of a Turkish bath just for an André Gidean laugh, who earned his role of guru by having lived coolly and defiantly on the margin of society after being born into its social center—St. Louis’s prominent Burroughs Adding Machine family and Harvard ’36. His intelligence was acute, penetrating, impersonal and sweepingly bizarre. Young Ginsberg was a “visionary” oddball from Paterson, New Jersey—“I never thought he’d live to grow up,” said hometowner William Carlos Williams about him—the son of a minor poet and a suffering crazy mother whom he has written beautifully about in Kaddish (1962), a radical, a Blakean, a dreamy smiling Jewish Fauvist, and one can picture the three of them bouncing ideas off each other during apocalyptic Morningside Heights nights just after America got sucked into the war.

…Jack Kerouac’s French Canadian-Catholic-Yankee arc was widened to compassionately include non-participating acceptance of the homosexuality of his literary pals, association with interesting criminals and prostitutes, drugs, Manhattan freakishness of every kind, including those crazy forays with Ginsberg, Herbert Huncke (ex-con. drugman and recent writer), Burroughs and Neal Cassady (Dean Moriarty of On the Road) into the hustling life of Times Square. An artist of originality, such as Kerouac, is compounded of many layers, his capacity for experience is always widening, his instinct for friends and lovers is based on what he can learn as well as brute personal need; one feels that Kerouac was expanding in all directions at this time, reading Blake, Rimbaud, Dostoevsky, Joyce, Baudelaire, Céline and the Buddhists now in addition to his groovy American word-slingers, beginning to write poetry (perhaps with Ginsberg’s enthusiastic encouragement), painting, becoming in other words the many-sided phenomenon he would have to become in order to escape easy definition and inspire the deep affection of such a variety of heterogeneous people as he eventually did.

When WWII finally did come, Kerouac signed on as a merchant seaman and sailed to arctic Greenland on the ill-fated S.S. Dorchester, now famous for the four chaplains who gave up their lives during a U-boat sinking near Iceland, but he had been called to Navy boot camp just before that fatal 1943 sailing. After a comparatively short duty in the Navy, Kerouac was discharged as “schizoid personality,” a primitive mental description not very different from the way a number of his fellow writers were bracketed by a service unable to handle their double and triple vision. Now he was to be on his own (except for his boyishly obsessive devotion to his mother, as his patient readers know only too well) for the rest of the race. After the Navy, the remainder of the war was spent as a merchant seaman sailing the North Atlantic again; then, in rough order, came a year under the G.I. Bill at Manhattan’s New School for Social Research, the completion of his first novel, hoboing and hitchhiking across the United States and Mexico, and the growing attachment for San Francisco as the first port of call after he came down from his perch on top of the Washington State mountains as a fire-watcher.

I can remember the word being passed around in New York in the late ’40s that “another Thomas Wolfe, a roaring boy named Kerouac, ever hear of him?” was loose on the scene (and I can also remember the shaft of jealousy that shot through me upon hearing this). But the significant thing was that in addition to hard, I-won’t-be-stopped writing during these crucial years—and this extra gland was to make Kerouac stand out from all the other first novelists clogging the city—he had an uncanny gift for winging right along toward new experience he was the first vocal member of a postwar breed, the Beat Transcontinental American, for in New York he numbered among his friends (and happily shook up) such writers as Burroughs, Ginsberg, Corso, John Clellon Holmes (who has a coolly memorable portrait of him in Go) as well as jazz musicians, painters, hippies, while on the Coast he had equally strong currents going with Neal Cassady—“the discovery of a style of my own based on spontaneous get-with-it came after reading the marvelous free narrative letters of Neal Cassady”—and the poets Philip Whalen, Gary Snyder, Peter Orlovsky (Simon Darlovsky in this book and Ginsberg’s loyal buddy), Philip Lamantia, Robert Duncan, John Montgomery and others.

Absorbing the life for his work by scatting around the country, Kerouac was also feeding scores of people by his presence enthusiastically daring the poets to wail the painters to paint, little magazines to get started (Big Table, 1960–1961, was named by him for its brief but significant career) and in the simplest sense being the human pivot for an improvised sub-society of artists, writers and young poetic-religious idealists alienated from our sapping materialistic culture. It doesn’t seem exaggerated to say that Kerouac by his superior capacity for involvement with “his generation” unified surprising numbers of underground Americans who would probably have remained lonely shadows but for his special brand of charisma. And Transcontinental though Kerouac was, the West Coast, and the Frisco area in particular, were to prove culturally more ready for him than the East.

California looks toward the Orient; its young intellectuals and truth-seekers are far more open to untraditional and experimental concepts than their counterparts in the New York and New England cultural fortresses, and it was to be no accident that the beat chariot fueled up in S.F. and then rolled from west to east in the late ’50s rather than the other way around. But more specifically for our knowledge of Kerouac, it was on the Coast, especially from Frisco north to the high Washington State mountains, that climate and geography allowed his Dharma Bums (1958) to combine a natural outdoorsy way of life with the Buddhist precepts and speculations that play a very consistent part in all of Kerouac’s writing and especially in Desolation Angels. In this propitious environment Kerouac found a number of kindred neo-Buddhist, antimaterialist, gently anarchistic young Americans whom he would never have come upon in New York, Boston or Philadelphia; they discussed and brooded upon philosophy and religion with him (informally, but seriously) and brought—all of them together, with Kerouac the popularizer—a new literary-religious possibility into the content of the American novel that anticipated more technical studies of Zen and presaged a shift in the intellectual world from a closed science-oriented outlook to a more existential approach. This is not to imply that Kerouac is an original thinker in any technical philosophical sense, although every artist who makes an impact uses his brain as well as his feelings; Kerouac’s originality lay in his instinct for where the vital action lay and in his enormously nimble, speed-championship ability to report the state of the contemporary beat soul (not unlike Hemingway in The Sun Also Rises some 35 years earlier).

“My work comprises one vast book like Proust’s except that my remembrances are written on the run instead of afterwards in a sickbed.”

Before Kerouac appropriated San Francisco and the West Coast, the buzz that had been heard in New York publishing circles about this word-high natureboy came to a climax in 1950 with the publication of his first novel, The Town and the City. From the title you can tell that he was still under the influence of Thomas Wolfe—The Web and the Rock, Of Time and the River, etc.—and although his ear for recording the speech of his contemporaries is already intimidating in its fullness of recall and high fidelity of detail and cadence, the book remains a preliminary trial run for the work to come. In it are the nutty humor, the Times Square hallucinated montage scenes, fresh and affectionate sketches of beats-to-be, intimate descriptions of marijuana highs and bedbuggy East Side pads, but at the age of 28 Kerouac was still writing in the bag of the traditional realistic American novel and had not yet sprung the balls that were to move him into the light. Kerouac himself has referred to Town as a “novel novel,” something at least in part madeup and synthetic, i.e., fictional. He has also told us that the book took three years to write and rewrite.

But by 1951, a short year after its publication, we know that he was already beginning to swing out with his own method-philosophy of composition. It took another seven years—with the printing of On the Road, and even then readers were shielded from Kerouac’s stylistic innovations by the orthodox Viking Press editing job done on the book—for that sound and style to reach the public; but Allen Ginsberg has told us in the introduction to Howl (1956) that Kerouac “spit forth intelligence into 11 books written in half the number of years (1951-1956)”—On the Road (1957), The Subterraneans (1958), The Dharma Bums (1958), Maggie Cassidy (1959), Dr. Sax (1959), Mexico City Blues (1959), Visions of Cody (1960), Book of Dreams (1961), Visions of Gerard (1963), San Francisco Blues (unpublished) and Wake Up (unpublished). The dates in parenthesis refer to the year the books were issued. At the age of 29 Kerouac suddenly made his breakthrough in a phenomenal burst of energy and found the way to tell his particular story with its freeing sentence-spurts that were to make him the one and only “crazy Catholic mystic” hotrodder of American prose.

This style, as in that of any truly significant writer, was hardly a surface mannerism but rather the ultimate expression of a radical conviction that had to incarnate itself in the language he used, the rhythm with which he used it and the unbuttoned punctuation that freed the headlong drive of his superior energy. He had invented what Ginsberg called, a trifle fancily, “a spontaneous bop prosody,” which meant that Kerouac had evolved through experience and self-revelation a firm technique which could now be backed up ideologically.

Its essentials were this: Kerouac would “sketch from memory” a “definite image-object” more or less as a painter would work on a still-life; this “sketching” necessitated an “undisturbed flow from the mind of idea-words,” comparable to a jazz soloist blowing freely; there would be “no periods separating sentence-structures already arbitrarily riddled by false colons and timid commas;” in place of the conventional period would be “vigorous space dashes separating rhetorical breathing,” again just as a jazzman draws breath between phrases; there would be no “selectivity” of expression, but instead the free association of the mind into “limitless seas” of thought; the writer has to “satisfy himself first,” after which the “reader can’t fail to receive a telepathic shock” by virtue of the same psychological “laws” operating in his own mind; there could be “no pause” in composition, “no revisions” (except for errors of fact) since nothing is ultimately incomprehensible or “muddy” that “run in time” the motto of this kind of prose was to be “speak now or forever hold your peace”—putting the writer on a true existential spot; and finally, the writing was to be done “without consciousness” in a Yeatsian semitrance if possible, allowing the unconscious to “admit” in uninhibited and therefore “necessarily modern language” what overly conscious art would normally censor.

Kerouac had leapt to these insights about Action Writing almost 15 years ago—before he sat down to gun his way through Road, which by his own statement was written in an incredible three weeks. (The Subterraneans, which contains some of his most intense and indeed beautiful word-sperm, was written in three days and nights with the aid of bennies and/or dex.) Whether or not the readers of Desolation Angels—or contemporary American writers in general—embrace the ideas in Kerouac’s Instant Literature manual, their relevance for this dungareed Roman candle is unquestionably valid. The kind of experience that sent him, and of which he personally was a torrid part, had a blistering pace-discontinuity-hecticness-promiscuity-lunge-evanescence that begged for a receptacle geared to catch it on the fly. At the time of Kerouac’s greatest productivity in the early 50s, the humpedly meditated and intellectually cautious manner of the “great” university English departments and the big literary quarterlies was the dominant, intimidating mode so far as “serious” prose went; l know from my own experience that many young writers without Kerouac’s determination to go all the way were castrated by their fear of defying standards then thought to be unimpeachable. So tied up were these standards with status, position in the intellectual community, even “sanity” in its most extensive sense, that writers who thumbed their nose or being at them had to risk everything from the categorization of simple duncehood to being called a lunatic. But Kerouac, “a born virtuoso and lover of language,” as Henry Miller accurately pointed out, was literarily confident enough to realize—with the loyalty of a genuine pioneer to his actual inner life—that he would have to turn his back on the Eliot-Trilling-Older Generation dicta and risk contempt in order to keep the faith with reality as he knew it. Obviously this takes artistic dedication, courage, enormous capacity for work, indifference to the criticism which always hurts, an almost fanatical sense of necessity—all the guts that have always made the real art of one generation strikingly different from the preceding one, however “goofy” or unfamiliar it looks and feels to those habituated to the past.

What many of Kerouac’s almost paranoically suspicious critics refuse to take into account is the fundamental seriousness, but not grimness, of the man; his studious research into writer-seers as varied as Emily Dickinson, Rimbaud and Joyce, the very heroic cream of the Names who rate humility and shining eyes from the brownnosing university play-it-safeniks; and his attempt to use what he has learned for the communication of fresh American experience that had no precise voice until he gave it one. This is not to say that he has entirely succeeded. It is too early, given Kerouac’s ambition, for us to make that judgment; but we can lay out the body of his work, 14 published books, and at least make sense of what he has already achieved and also point out where he has perhaps overreached himself and gestured more with intention than fulfillment. As with any creative prose writer of major proportion—and I believe without doubt that Kerouac belongs on this scale for his and my generation—he is a social historian as well as a technical inventor, and his ultimate value to the future may very well lie in this area. No one in American prose before Kerouac, not even Hemingway, has written so authentically about an entirely new pocket of sensibility and attitude within the broad overcoat of society; especially one obsessed by art, sensations, self-investigation and ideas. Kerouac’s characters (and he himself) are frantic young midcenturyites whose tastes and dreams were made out of the very novels, paintings, poems, movies and jazz created by an earlier Hemingway-Picasso-Hart Crane-Orson Welles-Lester Young network of pioneering hipsters. Nor are these warming modern names and what they stand for to Kerouac’s gang treated with distant awe or any square worship of that sort; they are simply part of the climate in which the novelist and his characters live.

We ought to remember that the generation which came of age in the late ’40s and mid ’50s was the product of what had gone immediately before in the dramatization of the American imagination, just like Kerouac himself, and his-and-their occasional romanticization of the stars who lighted the way was not essentially different from what you can find in any graduate school—only emotionally truer and less concerned with appearances. So credit the King of the Beats with having the eyes and ears to do justice to an unacknowledged new American Hall of Fame that was the inevitable result of our country’s increasing awareness of the message of modernity, but remained unrepresented in fiction until Kerouac hiply used it for his subject matter. Yet art is more than literal social history, so that if Kerouac is a novelist-historian in the sense of James T. Farrell, F. Scott Fitzgerald or the early Hemingway, he like them must show the soul of his matter in the form; the artist-writer’s lovely duty is to materialize what he is writing about in a shape indivisible from its content (“a poem should not mean but be”).

It therefore would have been naive and ridiculous for Kerouac to write about his jittery, neurotic, drug-taking, auto-racing, poetry-chanting, bop-digging, zen-squatting crew in a manner like John Updike or even John O’Hara; he had to duplicate in his prose that curious combination of agitation and rapture that streamed like a pennant from the lives of his boys and girls; and it is my belief that precisely here he stepped out in front by coining a prose inseparable from the existence it records, riffing out a total experience containing fact, color, rhythm, scene, sound—roll ’em!—and all bound up in one organic package that baffles easy imitation. In this sense art has always been more than its reduction to a platform—and it is interesting (in a nonjudgmental sense) that Allen Ginsberg and John Clellon Holmes have always been more articulate beat ideologists than Kerouac who has always squirmed out of any programmatic statements about his “mission” because it was ultimately to be found in the work rather than a Town Hall debate. Except for that machinegun typewriter in his lap—or head!—he was seemingly deaf and dumb or reckless (“I want God to show me His face”) and bizarre as a public spokesman; simply because this was not his job and any effort to reduce the totality of experience communicated in his books would have seemed to him, like Faulkner, a falsification and a soapbox stunt rather than a recreation—which is where the true power of Kerouac and narrative art itself comes clean. As Gilbert Sorrentino has pointed out, Kerouac accurately intuited our time’s boredom with the “psychological novel” and invented an Indianapolis Speedway narrative style that comes right out of Defoe—Defoe with a supercharged motor, if you will.

If Kerouac’s books are then to be the final test, and if the writing itself must support the entire weight of his bid—as I believe it must—has he (1) made his work equal its theory? and (2) will the writing finally merit the high claims its author obviously has for it? To begin with, we should consider the cumulative architecture of all his books since On the Road, because in a published statement made in 1962 Kerouac said: “My work comprises one vast book like Proust’s except that my remembrances are written on the run instead of afterwards in a sickbed…. The whole thing forms one enormous comedy, seen through the eyes of poor Ti Jean (me), otherwise known as Jack Duluoz, the world of raging action and folly and also of gentle sweetness seen through the keyhole of his eye.”

Let’s try to break this down. Kerouac regards his work as highly autobiographical—which it obviously is, with only the most transparent disguises of people’s names making it “fictional”—and a decade after the beginning of his windmill production he has found an analogy for it in Remembrance of Things Past. Proust’s massive spiderweb, however, gets its form from a fantastically complicated recapturing of the past, whereas Kerouac’s novels are all present-tense sprints which are barely hooked together by the presence of the “I” (Kerouac) and the hundreds of acquaintances who appear, disappear and reappear. In plain English, the books have only the loosest structure when taken as a whole, which doesn’t at all invalidate what they say individually but makes the reference to Proust only partially true. In addition, the structure that Proust created to contain his experience was a tortuous and exquisitely articulated monolith, with each segment carefully and deviously fitted into the next, while the books of Kerouac’s “Duluoz Legend” (his overall title for the series) are not necessarily dependent on those that have gone before except chronologically. Esthetically and philosophically, then, the form of Proust’s giant book is much more deeply tricky, with the structure following from his Bergsonian ideas about Time and embodying them; Kerouac, whose innovations are challenging in their own right and need no apology, has clearly not conceived a structure as original as Proust’s. As a progressing work, his “Legend” is Proustian only in the omniscience of the “I,” and the “I” ’s fidelity to what has been experienced, but it does not add to its meaning with each new book—that meaning is clearly evident with each single novel and only grows spatially with additions instead of unfolding, as does Proust’s. Finally, the reference to Proust’s work seems very much an afterthought with Kerouac rather than a plan that had been strategically worked out from the start.

If structurally the “Duluoz Legend” is much less cohesive and prearranged than the reference to Proust implies, what about the prose itself? I believe that it is in the actual writing that Kerouac has made his most exciting contribution; no one else writing in America at this time has achieved a rhythm as close to jazz, action, the actual speed of the mind and the reality of a nationwide scene that has been lived by thousands of us between the ages of 17 and 45. Kerouac, no matter how “eccentric” some might think him as a writer, is really the Big Daddy of jukebox-universal hip life in our accelerated U.S.A. His sentences or lines—and they are more important in his work than paragraphs, chapters or even separate books, since all the latter are just extensions in time and space of the original catlike immediacy of response—are pure mental reflexes to each moment that dots our daily experience. Because of Kerouac’s nonstop interior participation in the present, these mental impulses flash and chirp with a brightly felt directness that allows no moss whatsoever to settle between the perception and the act of communication. Almost 10 years before the “vulgar” immediacy of Pop Art showed us the astounding environment we actually live in—targeted our sight on a close-up of mad Americana that had been excluded from the older generation’s comparatively heavy Abstract Expressionism—Kerouac was happily Popping our prose into a flexible flyer of flawless observation, exactness of detail, brand-names, ice-cream colors, the movie-comedy confusion of a Sunday afternoon jam session, the spooky delight of reading Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in the woods of Big Sur, all sorts of incongruously charming and touching aspects of reality that were too slender and evanescent to have gotten into our heavyweight literature before.

The unadorned strength of the prose lay in the fact that no detail was too odd or tiny or inhuman to escape Kerouac’s remarkably quick and unbored eye; and because of his compulsive-spontaneous method of composition he was able to trap actuality as it happened—the literal preciousness of the moment—where other writers would have become weary at the mere thought of how to handle it all. Such strength coupled with humorous delicacy, and made gut-curdlingly real by the “cosmic” sadness especially in evidence in Desolation Angels, cannot be disregarded by anyone seriously concerned with how our writing is going to envelop new experience: “If it has been lived or thought it will one day become literature,” said Emile Zola. Kerouac’s influence as a writer is already far more widespread than is yet acknowledged or even fully appreciated, so extensive has its reach been; Ginsberg, Frank O’Hara, LeRoi Jones, folksinger-poet Bob Dylan, Hubert Selby, John Rechy, even Mailer, John Clellon Holmes, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and myself are only some of his opposite numbers who have learned how to get closer to their own rendering of experience specifically because of Kerouac’s freedom of language, “punctuation” (the etiquette of traditional English as opposed to American) and, in the fullest sense, his literary imagination.

Yet this same prose reveals itself as well to be at time little-boyish, threadbarely naked (so that you want to wrap a blanket around both it and its creator), cute-surrealistic-collegiate, often reading more like breathless short telegraphic takes than “writing” as we are accustomed to the meaning of the word. This is the risk—that the spontaneity is only paper-deep and can be blown away by a stiff new cultural wind. Since there is no “character” or “plot” development in the old-fashioned sense, only an accretion of details—like this—with the voice of the narrator increasingly taking on the tones of speech rather than literature—that it might have been taped instead of written—just as Jack taped four chapters of Visions of Cody—the words have a funny lightness—like feathers or kids’ paper airplanes—they trip along like pony hoofs—no deep impression left on the page—with a kind of comic strip implication—everything impatiently kissed on the surface—but is experience only that which we can see right off?

To be realistic, Kerouac’s writings can seem like nonwriting compared to our steelier literary products he has dared all on a challengingly frank, committed, unweaseling rhythmic fling that can get dangerously close to verbal onanism rather than our conception of fundamental novel-writing. The books themselves often seem like sustained underwater feats rather than “works” in the customary, thought-out, wrought sense. You get the impression that they landed between covers only by accident and that if you removed the endpapers that hold them together they would fly away like clouds; so light and meringuelike is their texture, so fluid and unincised their words, so casual their conception of art that they seem doomed for extinction the moment after they are set down.

The danger now confronting Kerouac, and it looms large, is one of repetition.

I find it inevitable, even for admirers, to seriously entertain the possibility that Kerouac’s work will not outlive the man and his period; already he has told us all his secrets and apparently bored—by the uninhibited exposure of his soul—readers who have no special sympathy for his rucksack fucksack romanticism. And yet this is the risk he has taken; the general reader to whom he has romantically exhibited his genuine being is as merciless as the rolling years, as uncharitable as winter, a restless and fickle as the stomach of a millionaire. One cannot help but think, poor Jack, poor Ti Jean, to have flung his innermost flower into the crass hopper of public taste and the need for cannibalistic kicks! My personal belief is this: whatever is monotonous, indulgent or false in Kerouac’s prose will be skinned alive by sharp-eyed cynics who wait with itching blades for prey as helplessly unprotected as this author is apparently condemned (and has chosen) to be. Kerouac has been flayed before and will be again; it is his god-damned fate. But I also believe that the best of his work will endure because it is too honestly made with the thread of actual life to cheapen with age. It would not unsurprising in the least to have his brave and unbelligerently up-yours style become the most authentic prose record of our screwy neo-adolescent era, appreciated more as time makes its seeming eccentricities acceptable rather than now when it is still indigestible to the prejudiced middle-class mind.

In subtle and unexpected ways haunted by the juvenile ghost of his childhood as he might be and therefore unnerving even his fondest intellectual admirers, I think Kerouac is one of the more intelligent men of his time. But if the immediate past has been personally difficult for him—and you will see just how painful it has been, both in Desolation Angels and in Big Sur (1962)—there is little to say that the future will be easier. He is a most vulnerable guy; his literary personality and content invite even more barbs, which wound an already heavily black-and-blued spirit; but the resilient and gently nub of his being—whose motto is Acceptance, Peace, Forgiveness, indeed Luv—is stronger than one would have suspected, given his sensitivity. And for this resource of his wilderness-stubborn Canuck nature all who feel indebted to the man and his work are grateful.

The danger now confronting Kerouac, and it looms large, is one of repetition. He can add another dozen hardcover-bound spurts to his “Duluoz Legend” and they will be as individually valid as their predecessors, but unless he deepens, enlarges or changes his pace they will only add medals to an accomplishment already achieved—they will not advance his talent vertically or scale the new meanings that a man of his capacity should take on. In fact one hopes, with a kind of fierce pride in Kerouac that is shared by all of us who were purged by his esthetic Declaration of Independence, that time itself will use up and exhaust his “Duluoz Legend” and that he will then go on to other literary odysseys which he alone can initiate.

Desolation Angels is concerned with Beat Generation events of 1956 and 1957, just before the publication of On the Road. You will immediately recognize the scene and its place in the Duluoz-Kerouac autobiography. The first half of the book was completed in Mexico City in October of 1956 and “typed up” in 1957; the; second half, entitled Passing Through, wasn’t written until 1961 although chronologically it follows on the heels of the first. Throughout both sections the overwhelming leitmotiv is one of “sorrowful peace,” of “passing through” the void of this world as gently and kindly as one can, to await a “golden eternity” on the other side of mortality. This humility and tenderness toward a suffering existence has always been in Kerouac, although sometimes defensively shielded, but when the Jack of real life and the hero of his books has been choked by experience beyond the point of endurance, the repressed priest and “Buddha” (as Allen Ginsberg valentined him) in his ancient bones comes to the fore. All through Angels, before and after its scenes of celebration, mayhem, desperation, sheer fizz and bubble, there is the need for retreat and contemplation; and when this occurs, comes the tragic note of resignation—manly, worldly-wise, based on the just knowledge of other historic pilgrimages either intuited by Kerouac or read by him or both—which in recent books has become characteristic of this Old Young Martyred Cocksman.

Like Winston Churchill—admittedly a weird comparison, but even more weirdly pertinent—Kerouac has both made and written the history in which he played the leading role.

Let no one be deceived. “l am the man, I suffered, l was there,” wrote Mr. Whitman, and only an educated fool—as Mahalia Jackson says—or a chronic sneerer would withhold the same claim for Kerouac. His mysticism and religious yearning are (whether you or I like it or not) finally ineradicable from his personality. In this book he gives both qualities full sweep, the mood is elegiacal, occasionally flirting with the maudlin and Romantically Damned, but revolving always around the essential isolation and travail that imperfect beings like ourselves must cope with daily. If critics were to give grades for Humanity, Kerouac would snare pure As each time out; his outcries and sobbing chants into the human night are unphony, to me at least unarguable. They personalize his use of the novel-form to an extreme degree in which it becomes the vehicle for his need and takes on the intimacy of a private letter made public; but Kerouac’s pain (and joy) become his reader’s because it is cleaner in feeling than the comparatively hedged and echoed emotions we bring to it with our what’s-the-percentage “adult” philosophy.

Like Winston Churchill—admittedly a weird comparison, but even more weirdly pertinent—Kerouac has both made and written the history in which he played the leading role. The uniqueness of his position in our often synthetic and contrived New York publishing house “literature” of the 60s speaks for itself and is in no immediate danger of duplication. If it goes unhonored or is belittled by literary journalists who are not likely to make a contribution to reality themselves, the pimples of pettiness are not hard to spot; Kerouac, singled out by the genie of contemporary fate to do and be something that was given to absolutely no one else of this time and place, can no longer be toppled by any single individual. The image he geysered into being was higher, brighter quicker, funkier and sweeter than that of any American brother his age who tried barreling down the central highway of experience in this country during the last decade.

But the route has now been covered. Jack has shown us the neon rainbow in the oil slick; made us hear the bop trumpets blowing in West Coast spade heaven; gotten us high on Buddha and Christ; pumped his life into ours and dressed our minds in the multicolored image of his own. He has, in my opinion, conclusively done his work in this phase of his very special career. And I hope for the sake of the love we all hold for him that he will use those spooky powers given to all Lowell, Massachusetts, Rimbaudian halfbacks and transform his expression into yet another aspect of himself. For I think he is fast approaching an unequal balance—giving more than he is taking in. Two-way communication is fading because during the last 10 years he taught us what he knows, put his thought-pictures into our brains, and now we can either anticipate him or read him too transparently. I sincerely believe the time has come for Kerouac to submerge like Sonny Rollins—who quit the music scene, took a trip to Atlantis, came back newer than before—and pull a consummate switch as an artist; since he is a cat with at least nine lives, one of which has become an intimate buddy to literally thousands of people of our mutual generation and which we will carry with us to oblivion or old age, I am almost certain he can turn on a new and greater sound if he hears the need in our ears and sees us parched for a new vision. He is too much a part of all of us not to look and listen to our mid-60s plight; to hear him speak—and it’s a voice that has penetrated a larger number of us than any other of this exact time and place, trust my reportorial accuracy regardless of what you may think of my taste—just turn the page and tune in.

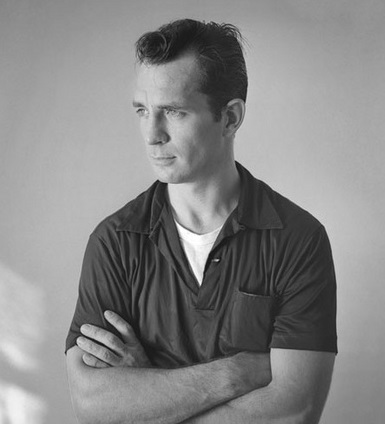

[Featured Image: Tom Palumbo Wikimedia Commons]