Pauline Kael has just turned seventy. An important birthday; her house in the Berkshires is filled with flowers from well-wishers. “I don’t want you to get the wrong idea that there are always this many flowers around,” she says with her nervous, melodic laugh. The rooms of her handsome, two-turreted stone-and-shingle house evidence a fine eye for American antiques: stained-glass lamps, wooden writing desks, quilt-covered beds—each item a bargain purchase, she notes with pride. Until recently, Kael—child of the Depression and Bohemia—has had to struggle financially. Now, it seems, her life is serene, well-ordered, almost pastoral. A copy of The Hobbit lies on her dining room table. It is a birthday present from her seven-year-old grandson, William, who has heard it read aloud and now wants to discuss the story with her.

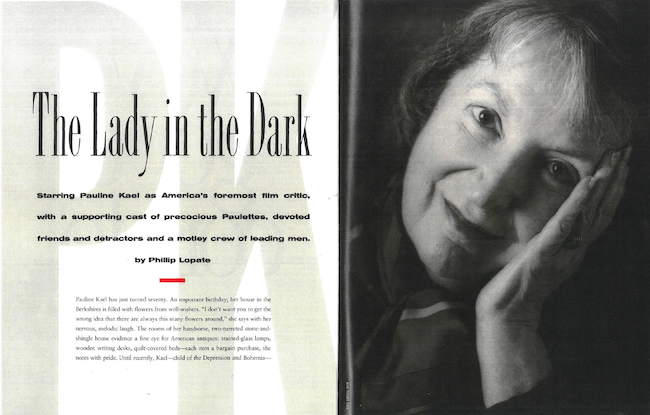

Can this pleasant, five-foot-tall grandmother in sneakers, with clear-rimmed glasses and white hair and round robin-red-breast figure, really be the scourge of film studios, the storm center of a dozen controversies, the acute and sometimes acidic critic whom Meryl Streep said she would kill if she could?

Rarely does one encounter an in-between take on Pauline Kael. She attracts a near cult following, which considers her the best film critic America has ever had and the keenest writer of critical prose since George Bernard Shaw and Edmund Wilson. Her friends and disciples say she is one of the most generous, thoughtful people alive. Her detractors regard her as manipulative, empire building, witchy, shrill, a reviewer of limited filmic sense whose judgments are often marred by personal obsessions and vendettas. Perhaps both camps are right, up to a point; each sees a different face of Pauline, this singularly complex woman.

Kael’s greatest strengths as a critic have been her passion for the medium and her analysis of scripts and acting styles. She is especially understanding of the way women come across on-screen. “Perfection going slightly to seed is maybe the most alluring face a screen goddess can have,” she wrote about Faye Dunaway. Or “Sally Field seems to have got the Jane Fonda bug—she’s being earnest and archetypal….” She has also been valuable in championing rogue filmmakers who operate within the Hollywood system. (On Repo Man: “A movie like this, with nothing positive in it, can make you feel good.”)

If she has sometimes overvalued shallow outbreaks of “fun” smuggled into studio schlock while reacting with antsy irritation to more visually formalist, contemplative or intellectually ambitious work by foreign directors such as Resnais, Rohmer, Tarkovsky, Losey—well, no one critic can do it all. Kael’s prose style, which manages to be flashy yet subtle and conversationally bonding with readers, remains the best of any film writer, so that even when she drives one up the wall, she is stimulating to read—no mean feat after thirty-five years of reviewing movies.

“I think I’ve definitely been given a harder time for being a woman. I’m called ‘hysterical’ and ‘aggressive’ and ‘opinionated’—which they would never call a male critic.”

The first time I met Pauline Kael, our conversation kept circling around her pain and puzzlement at the friendships she had lost through her reviews. Woody Allen used to be a friend until her Stardust Memories piece. Ditto, Coppola. If she gave someone a good review, she said, they seemed to think it was their right to be only praised from then on, and took it as a betrayal if she subsequently said something negative.

“You can’t get too close to these filmmakers,” she said. “They’re very devious—they have to be to get their pictures made. And it’s hard to write about them once you know them well, because you understand too much what’s behind the films. On the other hand, one tends to make friends with people who are in the business.”

Asked about some of the attacks on her in the press, she said: “I think I’ve definitely been given a harder time for being a woman. I’m called ‘hysterical’ and ‘aggressive’ and ‘opinionated’—which they would never call a male critic. I’ve been referred to in print as a ‘cunt’ by people I’d praised. The first time was by John Huston. We’d been friends and I’d defended him for years. But I wrote that The Night of the Iguana was a lousy movie. So he called me a ‘cunt’ to an interviewer. Then he wrote me a personal letter of apology!” She laughs disbelievingly. “Of course, the article would reach hundreds of thousands, while the letter would only be read by me.”

But she held no grudge, as her glowing review of The Dead testifies. From Huston, Kael went on to talk about the appetites of various directors: Rossellini’s womanizing (“A few days before his death, he was staying up till two in the morning trying to impress some twenty-year-old nitwit,” she sighed); Truffaut’s attraction to “vacuous young girls”; Welles’s and Peckinpah’s preference for “these lite muchachas.” Of all the directors she recalled, it was Sam Peckinpah who elicited her deepest feelings of affection.

“Peckinpah was such a dear man,” she said. “He started out as an actor, you know, in the Pasadena Playhouse. He’d invented that whole cowboy he-man past after the fact, and then he felt he had to become that way. We’d go to parties together at these Beverly Hills homes, and sometimes he’d arrive so drunk I didn’t know how we’d get out of there safely.”

I thought of Kael’s loving essay “Notes on the Nihilist Poetry of Sam Peckinpah” and her fondness for certain Hollywood “bad boys”: Peckinpah, James Toback, Robert Towne. I wondered if her attraction was purely vicarious, or if she had been involved with that sort of self-destructive, excessive type in her past. But when asked personal questions, Kael seemed very resistant and steered the conversation as quickly as possible back to films. She would say nothing more about her three marriages (as far as I know, the first two husbands’ names have never even appeared in print) than “We all make mistakes when we’re young. Do we have to talk about that old stuff?”

It’s clear from remarks in her books that Kael doubts the endurance of love or the value of marriage. One senses she has been romantically disappointed often and now is fiercely independent, free of all that messy longing—perhaps a victorious side effect of aging.

I noticed her hands and mouth trembling. She has given up alcohol (a previous preference), sugar and cream, on doctor’s orders. Like film buffs everywhere, we compared movies we loved as a mutual diagnostic probe. Her desire for a meeting of minds that would place us together in the inner circle of good taste was palpable and touching. She makes it so clear that she would like to think the best of you—and the best usually means that you agree with her.

Kael was born in 1919 in Two Rock, California, a town some thirty miles north of San Francisco. Her parents, Isaac and Judith, were Polish Jews who immigrated to America, where Isaac saved enough as a salesman and storekeeper to buy a chicken farm in Petaluma. The youngest of five children (her two brothers worked in business, and her two sisters have had distinguished teaching careers), Pauline spent her first eight years on the farm. It was an experience that marked her with a prickly pride in the Western way of life and an outsider’s chip on her shoulder regarding what she saw as the intellectually snobbish East Coast.

Kael’s family was big on reading, music, theater—and movies. Pauline went along with her brothers and sisters to the local movie house and remembered years later—far better than they would—their early crushes on silent-screen stars. She already had a phenomenal gift for recalling whatever she saw on-screen, which would allow her to write, sometimes decades after the fact, descriptions of film scenes still vivid in her mind.

In 1927 Kael’s father lost his money in the stock market and had to sell the farm and go back to grocery retail in San Francisco. “It was hard for him at fifty to start all over again,” she said. “He tried, but he was a broken man.” In Isaac Kael, resourceful inventor of a new farmer persona and courtly, adulterous (she reveals in her Hud review) cowman who died before reaching old age, one glimpses, perhaps, the model of the Sam Peckinpah type.

Kael went to the University of California at Berkeley in 1936, in the midst of the Depression. “There were kids who didn’t have a place to sleep, huddling under bridges on the campus. I had a scholarship, but there were times when I didn’t have food,” she told Studs Terkel in Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression. Studying philosophy, she worked her way through college as a teacher’s aide for seven courses at a time. She also loved dancing to jazz bands and hanging out with the young poets who later became luminaries of the San Francisco scene: Robert Duncan, Weldon Kees, Jack Spicer. Eventually, she fell behind in her own course work and dropped out, six credits short of graduation, for lack of the $35 summer session fee. She has no regrets, she says, about not getting her college degree—though her attitude toward academia ever since has been jaundiced and wary.

“I must warn you that I’m not a fan of Pauline Kael.”

Kael wandered off to New York City, staying for three years, and living with the poet Robert Horan. At the time she was interested in becoming a playwright. She then returned to San Francisco, where she became involved with the poet and filmmaker James Broughton, whose lasting importance in Kael’s life is that he fathered her only child, Gina James. Broughton, one of the major figures of American avant-garde film, who has made twenty-two movies, including the classic The Bed, says about their time together:

“In 1947 the poet Robert Duncan introduced us. Pauline was working at Brentano’s bookstore. I was making Mother’s Day, my first solo film. She helped with costumes and props, dressing actresses with funny hats. But she also sneered at our avant-garde filmmaking—she’s good at sneering. We were together that summer in a simple cottage in Sausalito. Pauline was always getting into terrific arguments about art with the painters who came around, and they’d leave antagonized. She can be very sweet, the velvet glove—but jungle red underneath.

“I don’t remember how we broke up. She never wanted me to marry her, I know that,” says Broughton, whose acknowledged bisexuality may have been a factor. “It’s sort of a Virgin Mary archetype: She wanted a child but not to have to marry or live with a man. Once she got pregnant, she departed. It’s curious how the pattern is repeated. Gina isn’t married now, and she has a child by herself.”

Gina was born with heart problems that required costly medical attention, and Kael took a series of jobs—seamstress, cook, textbook editor, ghostwriter, answering-service operator—allowing her to look after the child at home. Around 1953 she also began writing her first film reviews, which generated far more excitement than her efforts at playwriting. Kael realized she had stumbled on her métier.

KPFA, the Pacifica public radio station, asked her to do a regular show (unpaid) on the movies. Ernest Callenbach, longtime editor of Film Quarterly, remembers the program’s format: “First she’d invite a miscellaneous gaggle of people over for dinner at her house in Berkeley. They’d all drink a fair amount, and they’d see a movie and then show up at the studio a little sloshed and excited and talk about their reactions to the film. Her show was very popular; she had a sassy, caustic voice and it penetrated your mind. Her voice was powerfully attractive to some men, who called her for dates. ‘Well, honey,’ she’d say. ‘Maybe you ought to tell me what you think I look like.’ They would answer things like ‘tall, blond, statuesque.’ Pauline would say with that great laugh of hers, ‘I don’t look at all like that, but if you’re ready for anything, come on by.’ ”

One of the men who contacted Kael after listening was Edward Landberg, who had started his own repertory movie theater and who invited her to help him program it. She ended up managing the theater, booking films, taking tickets, answering the phone. The Berkeley Cinema Guild and Studio became an enormous success (the first superior repertory cinema in America, some say) and also the first twin movie house. Key to its popularity were the program notes Kael turned out, which were far more candid and informative than the usual brochure blurbs. Many Berkeleyites gratefully remember these legendary notes as providing, in painless form, the basics of a sound film education.

In the process of working together, she and Landberg became lovers and ended up getting married. The marriage lasted only two years; he went off to Los Angeles while she stayed behind to run the theater. When he came back with a new wife, he and Kael had a business argument and she quit.

“What happened to Landberg?” I asked Kael.

“He fell apart….It’s very sad,” she responded. “For a while he became a sort of guru. He was like a lot of those people in Berkeley who were very talented and intelligent, but who disapproved of you if you succeeded.”

“I must warn you that I’m not a fan of Pauline Kael,” says Edward Landberg. He is a short man with a white goatee and bloodshot eyes; he is wearing a tan vinyl jacket over a blue pullover and shabby, stained pants. A Viennese émigré with traces of an Old World accent, he has a certain warm cosmopolitan modesty, at odds with an edgy suspiciousness. He pulls out a large folder of poems, places them on the Formica table of a Berkeley Thai restaurant and begins reading, by way of introduction. The poems are fairly oblique, part Berryman satiric, part mystical—not very good. From time to time I catch a line about Miss Quill, his code name for Kael.

Then he puts the poems away and we talk.

“I had founded the Guild in 1952,” Landberg says. “I heard Pauline Kael speak on KPFA, and I read a few of her pieces in Partisan Review and Sight & Sound. She struck me as a bright, witty, gifted writer, a good wordsmith. So I sent her a note. At first I found her stimulating. But within a fairly short time the stimulus wore off. Why? She was a very vain, aggressive woman. She was desperately in need of adulation and flattery. She had a solid coterie of fifteen to twenty people around her in this ‘salon,’ mostly gay men, who related to her as the Queen Mother. There would be this constant aesthetic chitchat about nothing. When you think about someone who wants to talk about nothing but movies—no matter how good the movies are—think about the emptiness.”

“Why did you get married?”

“It was a matter of convenience,” Landberg says. “I don’t think either of us really wanted to get married. It was pretty much a business arrangement. She was good for the theater, and it helped keep her alive. I will say she was a very good housekeeper and cook.”

Says Sarris: “I was somewhat taken aback by her apparent conviction that she had done me a favor by blasting me in print. She insisted that I should be grateful for her having shown me the error of my ways.”

After Landberg remarried, Kael quit the theater with a flourish, printing her letter of resignation self-righteously on the program calendar. Once she had left, the theater continued to thrive for a number of years, says Landberg with touchy pride. “In fact I did an even better job with publicity than she had. I became a wealthy man.”

“Then why did you give up the business?”

“To anyone who has what I have—a messianic drive,” he says hesitantly, “it could never be realized through showing movies. I began to receive messages, in the way of Joan of Arc. I was receiving Revelation; or if I wasn’t, I thought I was. The way it works is that the pineal gland is the organ for hearing God….”

“Wait a minute, what do you mean, a ‘messianic drive’? Do you mean that you consider yourself… the Messiah?”

“Well, it’s obvious I can’t be Jesus,” he says. “But if I’m anybody, it’s Elijah. And if I’m right that I’m the Final Prophet, then they’ll have to hand over the Covenant to me. And then the world will be saved.”

He flashed his dimpled smile, which still contained a shade of the boulevardier’s skepticism within the fanatic’s glare; and I saw how he must have been an attractive man years ago. It was, as Kael had said, sad. How else could he top his ex-wife’s fame and filmic crusading, except by saving the whole world?

Kael eventually demanded a salary to continue her radio show. “It was a major crisis for KPFA because no one was paid there,” explains Ernest Callenbach. “She made a farewell broadcast which flat-out attacked KPFA for not supporting her. It was a godsend, actually, since it forced her into print.”

The most controversial essay she wrote for Callenbach’s Film Quarterly was “Circles and Squares,” a critique of director-centered, auteurist film writing (“the auteur theory is an attempt by adult males to justify staying inside the small range of their boyhood and adolescence….”) and of its main American proponent, Village Voice critic Andrew Sarris. This led to a good deal of bad blood between Sarris and Kael over the years. “When I wrote the piece,” she explained, “I thought of it as good intellectual fun—you know, a debate. I had Chick Callenbach send a copy in advance to Sarris so that he could write a reply. I was very surprised to discover how hurt he was by it. I wrote him a note saying we should meet. But he continued to be offended.” Says Sarris: “I was somewhat taken aback by her apparent conviction that she had done me a favor by blasting me in print. She insisted that I should be grateful for her having shown me the error of my ways.”

Kael tried hard to land a film reviewing job with one of the San Francisco newspapers so that she could stay on the West Coast. But, according to her friend jazz critic Grover Sales, “Pauline made them very nervous—maybe because she’d attacked the local critics so often. They wrote her off as some kind of nut. Pauline said, ‘San Francisco is like Ireland. If you want to do something, you’ve got to get out.’ ”

“At first I didn’t fit into The New Yorker,” she admitted. “I seemed too rambunctious for its pages.”

A hectic freelance period followed in the mid-Sixties, during which she wrote for McCall’s, Life, The New Republic, Vogue, Mademoiselle, The Atlantic and Holiday. She was becoming a nationally known writer, but she was also having run-ins with editors who rewrote or rejected her copy. A particularly scathing review of The Sound of Music for McCall’s (she called it “the big lie” and “The Sound of Money”) helped get her fired from that family magazine. When William Shawn, editor of The New Yorker, approached her in 1968 with an offer to become the magazine’s regular film critic for half a year (the other half going to Penelope Gilliatt) and promised not to interfere with or shorten her copy, Kael found her niche at last.

Still, the move from California to New York was “wrenching, especially at my age,” she said. And Kael, the Westerner taking potshots at the Eastern Establishment and its respectable journals, the working woman who resented the privileges of the “well-heeled,” suddenly found herself ensconced in the most comfortably middle-class, prestigious journal of all. “At first I didn’t fit into The New Yorker,” she admitted. “I seemed too rambunctious for its pages. You couldn’t even say a word like constipation because it would make people think of shitting! But gradually things have turned around so that now people associate me with the magazine.”

Indeed, the marriage between Kael and The New Yorker has proven to be one of the longest lasting and mutually beneficial in modern magazine history. She helped to alter the magazine’s genteel critical tradition with her more visceral, racy approach.

“When she writes something excessive, it’s often out of a desperate need to invent a better movie than the one she’s seen,” says Joe Morgenstern. “She falls prey to her capacity for excitement, which is a pretty honorable flaw.”

Kael’s method is to get down with a movie, turned on by its sexy, animal energy—even, at times, by its violence. A crude characterization of Kael’s aesthetic is that she goes for violent flicks. Actually her position is more complex, drawing the distinction between movies that require violence to make their aesthetic point (such as Taxi Driver) and those that she considers nothing but distasteful pretexts for watching people get blown away (such as Eastwood’s Magnum Force). What makes some readers uncomfortable is her honest insistence that the spectacle of violence can carry a libidinous charge—and “libido” is a very positive term in Kael’s critical lexicon.

The Seventies was her favorite decade: It brought her the work of directors such as Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Peckinpah, Coppola, Robert Altman, Bernardo Bertolucci—all of whom she not only championed but in some cases helped launch, but with whom she identified her own critical mission, following their careers almost with a manager’s personal zeal. Though very different, these filmmakers shared a liking for baroque excess—a roller-coaster approach given to sheer sensation and spectacle. Inevitably, Kael’s partisan enthusiasms sometimes resulted in hyperbole, such as the time she compared the importance of Last Tango in Paris to Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps or likened her favorites to the American Renaissance masterpieces of Melville and Emerson. And just as inevitably, there came a backlash: Kael was attacked by fellow critics Renata Adler, Richard Gilman, John Gregory Dunne and Sarris.

“People don’t understand something about Pauline’s particular take on reviewing movies,” says her friend Joe Morgenstern, a former Newsweek film critic. “When she writes something excessive, it’s often out of a desperate need to invent a better movie than the one she’s seen. She’s a romantic who gets smitten by certain movies—she loves their promise and refuses to be worn down by their defects. She falls prey to her capacity for excitement, which is a pretty honorable flaw.”

Adler’s 1980 attack in The New York Review of Books was singular, not only because of the school-yard thrill of a fight it brought to the literary world but because of the rarity of one superior prose writer analyzing another’s stylistic devices so closely (if vituperatively). Adler accused Kael of “compulsive and joyless naughtiness,” “strident knowingness,” “ad hominem brutality and intimidation” and “relentless, inexorable” images of “sexual conduct, deviance, impotence, masturbation,” as well as “indigestion, elimination, excrement.” One read it at the time with uneasy fascination, thinking that Adler was definitely onto something with her attempt to decode Kael’s recurrent erotic metaphors and scornful dismissals. The problem was that Adler knew so much less about movies than Kael, and that every good writer could be said to have psychosexual obsessions, and that the collection under attack, When the Lights Go Down—far from being “worthless,” which Adler had sweepingly concluded—in retrospect contains a good percentage of meaty reviews.

Kael made it legitimate to go into film criticism as a profession, and her influence on newer generations of film critics has been enormous. Some younger critics have been accused of aping not just her opinions but her quirky syntax and chummy use of second-person pronouns. These critics are called, in the trade, Paulettes. They resemble the Mafia in that many insist no such entity exists, while others see its conspiratorial roots everywhere.

Among the critics mentioned as having at one time or another been a Paulette are David Denby, David Edelstein, Hal Hinson, Elvis Mitchell, Terrence Rafferty, Ray Sawhill and James Wolcott. The present Paulettes often seem to vote as a bloc for National Society of Film Critics awards, and Kael has helped some of them get jobs. But she bristles at the notion that she has a “party line” that others slavishly follow.

“I don’t discuss movies with other critics before they write their reviews,” she said. “It would be totally unprofessional, and frankly, I’m not that interested in spending my life on the phone with kids half my age.”

One critic—among the many who asked to be anonymous—offered this observation: “It’s much more subtle than Pauline calling and telling her people what to think. It’s their trying to anticipate her taste. That’s a hard game to play, but a seductive one, especially if you don’t have an aesthetic of your own. Pauline’s style is so addictive to people of the movie-based generation. It lets you be smart without being stuffy, to pick up on the vernacular and the conversational, to feel sophisticated without needing to acquire much historical background. Also, things have to be ‘jazzy’ for her, which young people like too.”

An ex-Paulette told me, “She gives you the impression that she cares more about your writing than you do yourself. It’s a tremendous high to be appreciated by someone so powerful. Unfortunately there’s the desire to keep that high going—an addiction to her praise. It’s not her fault, it’s the fault of younger critics for allowing ourselves to be dominated by her.”

Still, the mentor-acolyte relationship is a power dance, and it usually takes two to tango. Another anonymous informant told me, “Pauline is both the Good Mother and the Monster Mom. She appears to be enormously nurturing, and then suddenly there’s this withholding. She’ll call you up and say, ‘It’s not very good, honey.’ Especially when you try to stretch yourself into something new.”

Joe Morgenstern vehemently denies this: “I’ve always found that when I’ve been at my most original, she’s responded with enormous generosity. And when I’ve been most predictable, she’s been tactfully silent.”

“I always know when I’ve had too much to drink because I want to sit down and talk to Pauline. I miss those conversations we had around her kitchen table on West End Avenue.”

As with so many issues regarding Pauline Kael, it is possible to put a positive or negative interpretation on the same facts. Why call it entourage or coterie and not set of friends? Perhaps the truth is more tangled. As Morgenstern puts it, “Pauline’s generosity is intertwined with the enjoyment of refereeing and brokering and having an influence.”

One night I watched Kael, surrounded by several members of her social circle—Lloyd Rose, Veronica Geng, David Chasnin, Allen Barra, Ray Sawhill and Polly Frost—viewing a rough cut of James Toback’s new movie, The Big Bang, at the director’s house. Clearly she likes being around attractive, bright people. She presided benignly, rarely holding forth, instead making sure everyone had a chance to speak, and extravagantly praising their latest articles. What does Kael get out of it? She has always been highly social, and perhaps, to some extent, she lives vicariously through younger people. They, for their part, seem held to her more by her maternal kindness than by any worldly favor she might do them. To earn the love of someone so articulate, accomplished and potentially dangerous—for one can never entirely forget “Grandma, what big teeth you have!”—must indeed be a heady experience.

One former Paulette willing to talk on the record is screenwriter-director Paul Schrader. “Pauline Kael was my mentor,” he says. “She got me into this business. I was going to a religious school, Calvin College, and my college and my church forbade films—therefore I got interested in them. I took some film courses at Columbia University. One night at the West End Bar I was vociferously defending Pauline’s book I Lost It at the Movies, and someone said, ‘Would you like to meet her? She lives nearby.’ So he brought me over to Pauline’s apartment on West End Avenue. We got to talking. It went on so late that I ended up sleeping on her sofa. The next morning she said to me, ‘You don’t want to be a minister; you want to be a film critic’ And if you ever want to go to film school, I can arrange it.’ Not only did she help me get admitted to UCLA film school, though I didn’t have the proper requirements, but thanks to her recommendation, I also began reviewing for the L.A. Free Press.

“I became one of a group of her satellites who would send her anything interesting by young critics,” Schrader says. “She read everything we wrote and would call when there was some film coming up that she felt had to be supported, to rally around. You have to understand that this was the evangelical period of film criticism. And she’s a proselytizer. She fills you up with energy and enthusiasm.

“Anyway, this satellite system increased her power and influence, naturally, since her opinion was multiplied in all these publications around the country. My falling-out with her occurred when there was an opening for a critic’s job in Seattle. Seattle was one of the best film towns in the country, and she needed a voice out there. She wanted to put me up for the job. Ostensibly it was everything I was looking for. But the idea of being yanked out of the film community in L.A. spooked me, so I turned it down and began writing screenplays, and fell out of that circle of critics. In a way, I had betrayed her investment in me.”

Did he think this estrangement had a role in her criticism of his movies? I asked. (Kael had written about Hardcore: “For Schrader to call himself a whore would be vanity; he doesn’t know how to turn a trick.”)

“I don’t take her criticisms of my films that seriously,” he says. “Besides, I didn’t end up making the kind of films I would have approved of as a critic myself….I always know when I’ve had too much to drink because I want to sit down and talk to Pauline. I miss those conversations we had around her kitchen table on West End Avenue.”

Kael is working on a review of Batman when I visit her in the Berkshires. She has just finished her second draft and is still not sure she has it right. It’s especially important because she is pro-Batman and feels the movie has been mistreated critically. “Canby just didn’t get it,” she says, shaking her head. (Kael often seems preoccupied with her powerful New York Times colleague.)

Gina comes by to type the penciled second draft. An attractive, shy brunette, she does all the typing and driving for her mother. Gina used to edit Kael’s pieces as well. “She was great at it,” says Kael. “But she felt she was too much inside my head; it made her uncomfortable.”

“When your mind is working well, when you’re clicking along as you’re writing, you think, Oh, I could do this forever! But when you get up from your desk, you’re god-damned tired and your body doesn’t want to move.”

The phone rings. An L.A. friend reports the “depressing news” that Sheila Benson of the L.A. Times panned Batman but loved Do the Right Thing, of which Kael disapproves. “And to think, I recommended her for that job!” Kael says with a weary smile.

Though Kael may be right in claiming she does not discuss beforehand new movies with her fellow reviewers nor campaign afterward for Film Critics’ awards, there is still the sense of a straw vote being taken, with various precincts around the country reporting in. The results are often disenchanting: She sees herself more often than not as waging a lonely crusade.

“She wants to correct us,” says Ernest Callenbach. For all her debater’s abrasiveness in print, Kael seems essentially a person who craves not pluralism but unanimity and harmony; and perhaps she gets it from her followers partly because they sense that need.

“Tell me about growing older,” I prod.

“What is there to say?” Kael says. “It’s not a happy stage. When your mind is working well, when you’re clicking along as you’re writing, you think, Oh, I could do this forever! But when you get up from your desk, you’re god-damned tired and your body doesn’t want to move. Some energy always feeds the writing, but the hell is waiting in line forty-five minutes for a screening you’ve been invited to or the sheer physical fatigue of trying to get to a movie on time. I mean traffic is terrible in New York: You can’t get a taxi; I often find myself walking in the rain, and I’m a soaking mess when I get there. In the winter it’s sheer misery at my age, slogging through wet streets.”

“Can you foresee a time when you’d stop doing it?”

“I think about it all the time,” she says. “But the fun of writing is still there. Things are coming up that I want to write about. And I need to earn a living…. Still, if you’ve written as much as I have, the phrases you’ve used before tend to come to mind. And you think, Omigod, this is senility. The real problem, though, is the flow of language. Before, the words just piled up and came out of the pencil—and they don’t pile up anymore. The circuits are not as accessible.”

In the late Seventies Kael passed out in a screening room and was rushed to the hospital. She was told that she had only a month to live. “I was supposed to go to L.A. to give a lecture,” she says. “The doctors told me that if I flew out I’d be dead before the plane landed. Finally I said, ‘What the hell, I may as well go, I need the money!’ ” Since that time, Kael has taken daily medication. One is aware of her as frail—probably very different from the hell-raising Pauline of days gone by, who could smoke a cigarette, apply lipstick and drink bourbon simultaneously, while letting fly a barbed remark.

In some ways, her old friends say, the change is for the better. “Pauline has mellowed,” says Grover Sales. “She’s less abrasive than she used to be. There’s a sweet quality to her now. Success has been good for her.”

In 1978, tired of reviewing and, at fifty-nine, feeling perhaps it was her last chance for a change of course, Kael took a leave of absence from The New Yorker and went to Hollywood. She was lured there by Warren Beatty to produce her friend James Toback’s movie Love and Money. Beatty, executive producer of the film, told her, “We need a third intelligence.” But there were casting problems, Beatty procrastinated as is his wont, and conflicts arose between Kael and Toback, who is known as much for his compulsions (gambling, picking up women) as for his intriguing movies. “In retrospect, she was right about a lot of things,” says Toback, “but it was very difficult for me at that point to collaborate.” She withdrew from the project but stayed on at Paramount as “executive consultant.”

Kael became answerable to Don Simpson, then head of production at the studio, and the two did not see eye to eye. She was frustrated by rejections of her proposals and by encounters with Production Hell: She’d work on a script with a writer until it reached satisfying shape, only to have the studio demand heavy rewrites. She became a court intellectual, not taken altogether seriously. No doubt, many in the industry who had long waited to see Pauline Kael get hers were not unhappy.

There is no shaking her or getting around her: This is a woman who has built a systematic life for herself. She has found a way to turn both her talents and limits to advantage, and she has no regrets—or none that she cares to express aloud

Kael declines to name which projects she worked on but adds with typical self-certainty, “When they took my advice, the films turned out better, and when they didn’t the films came out worse.” She insists she had a pretty good time in Hollywood.

Morgenstern says otherwise: “It was certainly a terrible, shocking experience for Pauline. She got a heavy reality bath when she came out here. It was out of an ardent love of movies that she threw herself into the arms of the movie goddess. And nothing came of it. It’s never pleasant to be part of a movie that never gets made, or is made in a distorted way.”

After six months, she ended her film producing career and returned to The New Yorker somewhat reluctantly, though the job was now sweetened by no longer having to share it with Penelope Gilliatt. Kael had her revenge on the studios with a long jeremiad called “Why Are Movies So Bad? Or, The Numbers.” Some called it sour grapes; others censured her Hollywood episode as a potential conflict of interest. A careful reading of Kael suggests she has too much blunt honesty to falsify her critical opinions. The one reproach to be made about her Hollywood ties is a tonal one: that inside tipster’s tone that seems to want to address the industry not just as a critic but as a player. Her Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes review, for example: “[Robert] Towne’s script, which I’ve read, was marvelously detailed…. [It] exists now only in vestigial form; it’s in some of the bits and pieces of [director Hugh] Hudson’s scraggly mess, and Towne uses a pseudonym in the credits—P.H. Vazak, the kennel name of the dog he loved, who’s now dead.”

Kael is not as powerful in the marketplace as she once was, but that perhaps has less to do with any personal decline than with the fact that movies are no longer as central to American culture as they were in the Sixties and Seventies. Indeed, her latest collection, Hooked, shows her to be just as feisty, probing and passionate about movies as ever, even if there seem to be fewer important ones to write about.

Some consider her too movie-mad. “As far as I know, Pauline Kael has no general conversation,” critic Richard Schickel has said. “She talks only about movies. She’s a bit of a monomaniac.” And Broughton remarked, “She’s only real, if she’s real at all, in that movie theater. It’s still her whole life. She has a complete passion for something that’s evanescent. But since she has total recall, which is the most remarkable thing about her, maybe it’s not evanescent for her.”

“It’s not correct that movies are her only life,” says Morgenstern, who is closer to Kael. “But her movie life is as intense as anyone’s I know. We’ll pick up the phone and talk a little about the world, then get down to the meat of it: ‘Okay, so what have you seen lately?’ There have been times when we’ve had intensely personal conversations—more lately than when I first knew her. I’ll tell her all my problems. If I want Pauline to be the sort of friend she’s capable of, I have to push another button and say, ‘Let’s leave movies for a while.’ But there is that obsessive attachment to movies. She’s really a very private person, even with all the people streaming through her life. Very often, I think, the movies are a defense for her against the messiness of the rest of the world.”

One informant told me, “She comes into town, sees a few movies, goes back and that’s it. The person is all there in the writing. She has no life.” Yet Kael has, after all, her daughter and grandchild, her friends, the Berkshires, New York City, a wider cultural curiosity than most film critics, her health problems, economic concerns, interest in world affairs. The curious part is not how limited her life may be but the need for others to characterize it as narrow. Perhaps it’s because Kael makes people uncomfortable with her unrelenting focus on movies. Yet movies are only her vehicle to talk about behavior, society, politics, morality, art. Perhaps what appears narrow is that self-sufficient asceticism that comes from having turned herself into a pure writing instrument—that stripping away of practical barriers that is typical of very disciplined, productive writers.

There remains a puzzling gap between the appealing, commonsensical, serene Pauline Kael I interviewed on several occasions and the embattled, armored, almost bitterly self-righteous quality that crops up occasionally in her writing. Kael has a rationale for everything she does, and when you are with her, you see the world her way. She has her own kind of charisma: Her voice is seductively caressing, and she looks at you with those startled blue eyes, the way a child can seem to be all face, vulnerably attached to a small body, and you want to agree with her every word and protect her. Only in leaving Kael-land do doubts enter.

The Pauline who never admits she is wrong, who will not allow those who disagree with her a dignified out but insists on portraying them as prim, hypocritical, immature, who is famous for her devastating put-downs yet who steadfastly refuses to acknowledge her cruelty, or who remains surprised by the pain her harsher writings cause—that Pauline seems either a little unconscious, or not very given to examining her own dark side. “Her particular myth,” says the informant, “is that everyone else has motives and an unconscious desire for power—except her. She alone is disinterested.”

Perhaps self-skepticism would be a luxury in a woman of her generation who has had to battle for a place in the previously all-male major film critics club. Other achieving women her age or older—Martha Graham, for example—have that same quality of refusing doubt. Reviewing is a profession, in any case, that tolerates little uncertainty, and Kael has excelled by trusting her gut intuitions. The limit of that approach, however, is that it prevents her from adjusting her views in the light of later experience. Kael is famous among film critics for not seeing movies more than once. When I asked her why, she said, “Who wants to find out you were wrong the first time? Besides, most movies would bore me a second time.” Another critic might wonder which films got by the first time only on surface sensation and which deepened as art. But that would lead Kael into a sort of historical scholarship at odds with her love of movies at first sight. The paradox of Kael as a critic is that she has one of the best analytical minds around, but her antagonism to film theory and academic film study, her mistrust of intellectualism, often restrict her to reacting to whatever promising teen movie comes out next. Yet her fans would insist that this serious monitoring of popular culture is precisely what makes her so valuable.

So Kael stands at this point—movingly fragile, complicated, full of old angers and new composures—with her loneliness, her pride of achievement, her disappointments, her wisdom, her hospitable kindness. She has no interest in writing her memoirs or longer works of film study. “I like writing about a subject and getting rid of it in a week and going on to something else,” she says. “It’s fun for me.”

There is no shaking her or getting around her: This is a woman who has built a systematic life for herself. She has found a way to turn both her talents and limits to advantage, and she has no regrets—or none that she cares to express aloud. Early on, Kael struck me as perhaps the most well-defended person I had ever met, but now that seems unfair. It is simply that one is unused to meeting someone who has so come to terms with her destiny. To a self-doubting neurotic New Yorker, such certainty inevitably suggest the possibility of self-deception. But for her it is really a matter of passion, first and foremost. Pauline Kael has always required and responded to passion, that true faith of the compulsive gambler, the go-for-broke romanticism of Altman and Peckinpah movies. That is her deep appeal to other romantics. Those of us who are skeptics may never fully grasp what is involved, though we shudder and admire.

[Featured Image: “New York Movie, 1939” by Edward Hopper, courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.]