Men of power sit at her feet. Mamelukes lift her chair from room to room while menservants trail her, carrying wine. The mayor seeks her ear to confess his wounds, the governor to confide his ambitions. When the seat of court moves with her to East Hampton in midsummer, labor ministers and publishers and political pundits endure long journeys to be by her side. Anglo-Saxon princelings execute perfect jackknives in her swimming pool; her regal daughters deferentially pass hors d’oeuvres. After dinner she coils into the cushions. Drawing up long, silken legs beneath her, she assumes a lotus position, then bids the most interesting men to her side. And now she begins the spinning of her tale. Dukes of finance and pretenders to the throne hang on her every word, mesmerized by this ageless Scheherazade. Like the legendary princess of The Arabian Nights who saved her life with 1,001 twists of plot, she alone has found a way to tame the kings of the City of Brass.

“When I’m not married I wish I were,” she will drawl, presenting herself first as a mere prisoner of love—and incidentally, four matrimonial ventures—“but when I am married I wish I weren’t!” The fickle feline stroke. Next, knowing full well the attraction of men to ambiguous danger, she will describe herself as a dictator: “My third husband told me that one should always praise before one criticizes. But I never remember to do that. I don’t say anything when my employees have done well—if I ever think they’ve done well” … ah, but she mutes it by laughing capriciously into her wine. A breath later she will drop a “Dollyism,” one of those deadly blunt remarks which only this Dolly could get away with, such as: “Most people to me are nothing but personnel problems.”

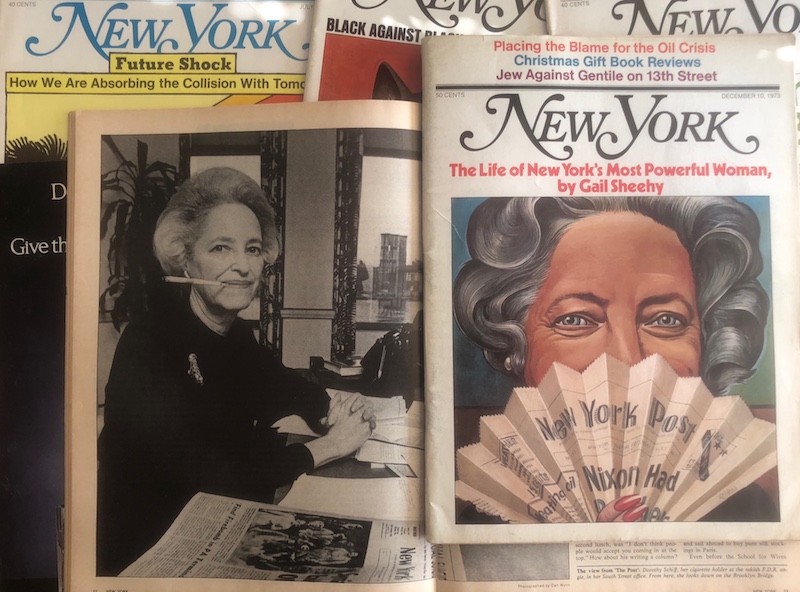

Now that she has them under her spell, she extracts from her tiny silver bag of tricks a wand—her ever-present white cigarette holder—and draws her listeners still closer to her lips. They fumble to give light to her Kool. She clamps the holder to one side of her mouth, a lusty mouth painted Passionata Pink. Swathed in smoke, she coils deeper into her asp-like neck. The forehead is clear as gauze, the blue eyes revealing as plate glass. Long fingers fan out across her cheek like ivory tusks. And now, with all ears straining to hear her vague, velvet-sheathed words, she will ask the ritual question:

“Do you think I should sell The Post?”

But before the men of power can pin her down, our Scheherazade disentwines from her lotus position and is transformed. All at once she becomes Dorothy Schiff: publisher, owner, and sole stockholder of the largest-circulation 15-cent afternoon newspaper in the country. (There is one other minor stockholder, the New York Post Foundation, but Mrs. Schiff is the sole contributor to the foundation.) She is a woman who prefers to come alone to parties so that she can leave when she damn pleases. Everette, her faithful chauffeur, will be waiting in the Fleetwood outside. Before one can say “Babylonia” she has evaporated into the pearly leather interior, leaving the end of her tale for yet another night, unfinished.

Since 1939, when she acquired the paper, this Scheherazade has spun her tale up to its most interesting point, and then stopped. Every night she has saved until last the Treasure Key—the key to control of The New York Post—which is what her story starts and ends with. This process having gone on for roughly 12,401 nights, one might think men would have got the hang of it. But no. It has been their habit over the years to call the king’s granddaughter the next week, to wine and woo her, propose to her, or petition to work for her, to battle and exit and return to her employ, or to battle and ride off into eventual oblivion, or to wait out dutifully the days and nights and years with the faint hope it will be they by her side when at last she finishes her tale—the male vanity expecting always that it is the nature of woman to want to turn over the reins.

This miscalculation has resulted in scores of attempts to buy the paper. Sterling-silver names such as Tom Finletter and Eleanor Roosevelt tried to raise funds to buy it, when they fell for a rumor that Mrs. Schiff was about to sell to a man they didn’t trust. Walter Thayer approached Mrs. Schiff with some sort of merger scheme during the last wobbly months of The Herald Tribune; she can’t recall the details. The dross are ignored. Attractive investment bankers and handsome publishers may be permitted to court her for years, subtly. There is only one rule: at the first mention of a balance sheet, Dolly will banish the suitor to her lawyers or bankers.

“Looking back, so many people have been in or out,” she drowsily plumbs her memory, “I can’t even remember the names. They talk for a while and then always want to see the figures, which they are not shown.” Need the lady remind her pursuers? “I don’t have to give an account of operations to any stockholder except myself.” She remembers one opening bid by someone very well known … maybe three or four years ago … ho hum. “But I didn’t go on with it … I think it was 40 million.” She never goes on with it “Because,” as the lady confides, “I’m not serious.”

The other miscalculation provoked by her infinite yarn-spinning is that she wants, needs, if only she could find, the right young man to run her kingdom. God alone knows how many satraps, including Bill Moyers when he left Newsday and James Brady when he was ousted by Harper’s Bazaar, have been seized by fevers of expectation sometime between the first and third lunch with Dorothy Schiff. As Brady recalls the sequence, she phoned the day his availability was announced in the morning paper. “I need a strong young man to run The Post,” was how she opened her tale at their first meeting. Brady immediately proposed himself as editor. Part Two of the tale, as he remembers from the sloughs of despair into which he was cast by the second lunch, was “I don’t think people would accept you coming in at the top.” How about his writing a column? she suggested. And by their third session, the whole notion was made to seem the figment of an eager young man’s imagination.

These men of power and ambition call her Dolly, but she eludes all of their stereotypes for explaining women. It is masks they see, masks behind which Dolly can maintain her ambiguity, guard her strength, cultivate rivalries for her favor, and ultimately accomplish what Scheherazade had in mind: to amuse the vengeful sultans for so long that they will bestow upon her their affection and spare her the traditional fate of her sex.

Who is the real Dorothy Schiff? Tyrant? Dizzy dame? Temptress? Professional rival? Submissive wife? Dominating wife? Queen mother? Liberated woman?

Bear in mind that she is the granddaughter of the grand vizier of German Jewish Grand Dukes, Jacob Schiff. The mightiest of bankers and an unregenerate patriarch, he seriously traced his ancestry back to King Solomon of Israel and a tradition 3,000 years old. It decreed that women were born only to be maidservants, women of pleasure or dowered brides to be bartered in the interest of cementing relations between men. Little had changed on that score by the 1870’s for the progeny of German Jewish bankers. As Stephen Birmingham in Our Crowd has taught us, “The mothers of the crowd studied the marriage market for suitable partners, while fathers studied the upcoming crop of young men as possible business partners.”

And so, as King Solomon had secured his position among his more powerful neighbors by marrying the Pharaoh’s daughter, Jacob Schiff’s wedding to the daughter of Solomon Loeb begat him a full partnership in the firm of Kuhn, Loeb & Company. It wasn’t much of a game for his wife, Therese Loeb Schiff. A shut-in among the Victorian horrors acquired by Jacob to outdo her father, she existed on the damask conversation that substituted for thought at tediously formal weekly “at homes” with her friends.

The lot of rich fraus in the banking crowd had not changed substantially by the year 1903, when Dorothy was born to Mortimer and Adèle Neustadt Schiff. Except that instead of confining her ritual rounds of shopping and empty tea chatter to mid-Manhattan, Adèle Schiff could gather up maids, valets, dogs, trunks, children, and potty chairs and sail abroad to buy pure silk stockings in Paris.

Even before the School for Wives went to work on young Dorothy, she had aberrant thoughts. From earliest girlhood she endured the formal Friday night dinners at Grandpa Schiff’s only by plotting how to escape from the drawing room where women were sent to babble about clothes and baby diets. Her whole life has been about gaining entrance to the smoking room, where men discuss the fate of the world.

To this end she has had to fashion the masks that would keep them guessing. Who is the real Dorothy Schiff? Tyrant? Dizzy dame? Temptress? Professional rival? Submissive wife? Dominating wife? Queen mother? Liberated woman? She has played all of these parts in her time and emerged a hybrid for which we have no name, no precedent. Each part has afforded its joys and exacted its price, concocting of her life one of the richest extravaganzas of our century. It seems a saga worth reviewing in these times of tumult for women, because this is one heroine who loves love as passionately as she cherishes her free will. She has dreamed every fairy tale, attempted every compromise, bounced back from real life’s unhappy endings, and finally made her choice—never settling for the most hackneyed role of all: woman as victim. Dorothy Schiff, formerly Hall, formerly Backer, formerly Thackrey, and lastly Sonneborn, is, judged by the male standard, a winner.

From the outside, watching her change disguises, it looks like this:

The Tyrant…

In this guise Mrs. Schiff is sequestered behind the green-and-white paneled doors of her office at 210 South Street, an office which, in texture and dimension, resembles a grass tennis court. Her windows command a view so broad, from the bridge at 59th Street to the Brooklyn Bridge at her feet, that the East River seems a mere moat encircling her castle. A limousine grazes always at the gate. Among the 1,400-plus employees arranged on the five floors below her, there are those who have served The Post for 25 years and have never set eyes on their majesty. Her archers and saddlers labor in the beery disorder of one big city room. They may see her once a year, at Christmas time. Her palace guard is positioned at opposite ends of the edifice. Editorial Page Editor James A. Wechsler is at one end and Executive Editor Paul Sann at the other; they rarely speak. Both communicate directly up the stepless pyramid, by telephone or memo, and wait for orders to come back down from the apex. Below all this her galley drudges pull the oars of the press room, their profanity unheard. “I wouldn’t go down there,” says the Queen. “The men often walk around in the nude.”

A male magazine publisher is expected for lunch. He will find her seated at an antique partners’ desk—the delicious irony of it! A partners’ desk, with its two facing kneeholes, is designed for equals to work together; scarcely a situation that Dorothy Schiff has encouraged. On the contrary, she refers to the chair opposite hers as “the hot seat.”

She is giving the publisher a tour of her suite of offices, space occupied by the women’s department of The Journal-American before Dolly bought the Hearst plant. She leads him into a large adjoining room appointed with a grand table and formal chairs of the sort one associates with cabinet meetings.

“So, this is your board room?” the publisher assumes.

Dolly blinks not. Patting her hair, she corrects him in her inimitable doesn’t-everybody? drawl: “I don’t believe in boards.”

Neither does she believe in unnecessary mingling with the working proles. An invitation to lunch with Dorothy Schiff is not unlike an investiture at Buckingham Palace. When Robert Spitzler received his summons, he rushed home to change into a Cardin suit and was subsequently named managing editor. The chosen, a handful of city room employees who receive regular invitations, have several things in common. Young, beautiful, blond, and born WASPS, they are drawn from what Mrs. Schiff refers to as “the management class.” Warren Hoge, her metropolitan editor, qualifies because he is the brother of Jim Hoge, editor of The Chicago Sun-Times. William Woodward III, who began as a reporter and was temporarily knighted last summer as her assistant-publisher-without-title, qualifies on all counts plus a bonus. He is the golden-haired grandson of the former chairman of the Hanover Bank. It goes without saying that the granddaughter of Jacob Schiff, the greatest German-Jewish financier of them all, is partial to investment bankers.

What with all the rivalry that precedes the invitation, one might expect lunch with Dorothy Schiff to be a lavish affair. Fact is, she divides all the world into three sandwiches. Corned beef for Jews, tuna fish for Catholics, roast beef for Prods. (She has them sent up from the plant cafeteria, and once her secretary has recorded your sandwich, nothing short of religious conversion can change it.) Only once did a guest demand chicken. Dorothy had to make the sandwich at home and bring it to the office in a paper bag.

When Dorothy Schiff tells the story of her first official visit from Katharine Graham, publisher of The Washington Post, one does not hear about the debate of summit issues between the two most powerful women in America. One hears about the sandwich negotiations.

“When we made the date, I asked her what kind of sandwich she wanted,” Mrs. Schiff will recount. “And she said ‘What are you having?’ And I said ‘Well, I always have the same thing, but you don’t have to.’ And she said ‘No, no, I want exactly what you’re having.’” To make a long story short, they both had BLT’s on a plastic-covered card table.

On another occasion protocol defined more clearly the difference between the two women. Mrs. Graham invited Mrs. Schiff to a seated dinner at her Manhattan apartment in the United Nations Plaza. Dolly had barely attached herself to the most interesting men at the table—Los Angeles Times publisher Otis Chandler and Mayor Lindsay—when Katharine Graham rose and signaled the men to remain seated, while she led the ladies out of the dining room. What barbarism! Lèse-majesté! Here was the mighty and courageous widow Graham, the woman who later defied a President and printed the Pentagon Papers, still slave to the most insulting form of upper-class sexual segregation.

“I was irritated,” Dorothy Schiff says with polite restraint. (Nowadays, Mrs. Graham no longer separates the men from the women and, if the men walk off at someone else’s dinner party, Mrs. Graham will quietly leave.)

Dorothy Schiff has earned within the New York newspapering trade the highest accolade of which its men are capable. She is known as “the only publisher with balls.”

But only six months ago, the Queen complains, “the same thing happened to me at Nelson and Happy’s.” There she was at the Rockefellers’ Fifth Avenue triplex, zealously eavesdropping on an ambassador, a Cabinet officer, and a governor over dinner, when Mrs. Rockefeller reluctantly led the ladies to retirement. Embarrassed by her own action, the governor’s wife whispered to the powerful publisher, “Don’t you want to hear what they’re saying?”

“I certainly do,” Dorothy Schiff said.

“Let’s go in, then,” Happy Rockefeller suggested.

“No,” said Dorothy Schiff, “you tell them to come out.”

From the privacy of her own duplex in the East Sixties, the owner of The Post is able to exercise her autocratic powers more easily. On the Saturday morning she expected this writer, war broke out in the Middle East. Mrs. Schiff awoke to the 8 a.m. news. Her first response was to switch hats from publisher to editor. She woke up Paul Sann and told him to hang up his executive vest, pack his foreign correspondent’s khakis, and be on the afternoon plane to Tel Aviv. Her next response was that of the journalist. Should she rush down to her city room? No, she would only get in the way. Instead, she phoned the office to tell them to keep her up to the minute on wire service reports, and then phoned me to relay “It’s very exciting.” By the time I arrived, she was pacing around her TV room with a portable radio clasped to her ear and ready with response three. Newsstands were closed for Yom Kippur, and I complained of having a devil of a time buying a copy of The Post’s Extra edition. Mrs. Schiff’s next words were those of a publisher:

“Another break for the Sunday Times.”

In her tyrant’s mask, there is no telling when Mrs. Schiff will abrogate the authority of her editors. “The boys,” she calls them, as in her explanation to mass transit advocate Theodore Kheel when he phoned to ask why she hadn’t run an editorial supporting the transportation bond issue. He was about to go on the air with his last pitch. She was for it, wasn’t she? “Oh yes, but the boys have reservations.” A beat. “We’ll be for it tomorrow.”

Of her flaming memos to Paul Sann regarding news coverage, she admits “They’re horrible—I’m not terribly careful or diplomatic.” She talks with James Wechsler once or twice every day by telephone. “He knows which are the sensitive areas,” she says, “and 99 per cent of the time he will send me an editorial before publication if it’s in an area where we might not agree—usually on a political endorsement.” But save for the whimpers of those who work for her, and are under orders not to talk, Mrs. Schiff’s imperial manner evokes amazingly little ill will. So naturally does she deliver her bold strokes, they bring a smile even as breath is knocked out. When city fathers say “She has guts,” they don’t grind their teeth. When Ted Kheel says “She is a charming and very tough lady,” he adds respectfully, “and I think she’s a good newspaperwoman.”

For all these characteristics, but particularly for the backbone she has displayed over the years in dueling with the craft unions and marching to her own drum among the publishers, Dorothy Schiff has earned within the New York newspapering trade the highest accolade of which its men are capable. She is known as “the only publisher with balls.”

The Dizzy Dame…

She never said she was an intellectual. Nor was she raised in a family of intellectuals. “I had yearnings that way, but never really got there,” she offers unapologetically. From the time she began cutting gym at Brearley to sit in the balcony of the Plaza movie theater and smoke cigarettes, and more decidedly, after losing the battle with her mother over college—Adèle Schiff wouldn’t allow her daughter more than a feeble stint at Bryn Mawr for fear she would become a “bluestocking,” consigned to the unmarriageable heap of eggheads—all her life, then, Dorothy Schiff has cultivated a love of gossip and the soapy side of life.

“I’m told I have the common touch.” It is in this statement that she takes the greatest pride. The intellectuals hated Love Story. She adored it. Her favorite book of the last year was written by Jackie Susann. “And I thought there was a lot of wisdom in it, too.”

Dolly’s sentences do trail off like ether. It does seem that everybody in town has a favorite “Dollystory.” And in truth, she rarely lets a conversation pass without probing personal relationships. Therefore, some people find it convenient to dismiss Dorothy Schiff as a silly woman. Or even believe it. She doesn’t seem to mind. It gives her a cover. My observation over the past five years, and that of those who have watched her at work, is quite the contrary: this is a remarkable person.

Interrogating the powerful and phone-polling the knowledgeable comes as naturally to her as blinking. She is constitutionally incapable of entering a room without cornering the most interesting man. “Soul-searching” was the 1920’s phrase her first husband used to describe it—Dolly’s little reflex—and it irritated the life out of him. “There would always be somebody interesting at a party and I’d find out as much as I could about him,” she explains. “Now it’s part of my job, but I think I’ve always done it.”

Accustomed as she is to sitting at the right hand of rulers, the sauce of human shyness is unknown to her. Dolly inevitably comes up with the what-everybody-wants-to-know-but-doesn’t-dare-ask question. And then she sits back smoothing her nimbus of silver hair, overtly deserving the answer, guileless as a queen mother who wants to know why the crown prince didn’t eat his spinach. Lest one think the answers are lost on her, one should check the copious notes and countless tapes of Dorothy Schiff. She does. Every time she meets an interesting man, she goes home and calls for clips on him from The Post’s morgue.

“Most of the people I see are quite high up. I find that first-rate people have never said to me, ‘This is off the record.’ Roosevelt never said it, the Kennedys never said it.” Henry Kissinger was different.

Kissinger was very anxious for a meeting with Mrs. Schiff last April. It was finally arranged by Happy Rockefeller, who called Dolly to say “Sunday night the 29th, just the four of us.” But there were five, because he brought Nancy Maginnes. “She didn’t say anything,” Dolly noted with a touch of superiority in her voice. She cornered a willing Kissinger for three hours—as the man stated, power is the strongest aphrodisiac. He ran through all the nations of the world and gave his opinion. “He put everything off the record,” but our veteran soul-searcher was not to be outfoxed. “I have my own report of it, as I have made such reports many times in my life. Eventually, the time when it’s off the record passes and what he said can be used.” Over the years the results of her expeditions have been dictated to her administrative assistant, Jean Gillette, and more recently taped by her working biographer, Jeffrey Potter, whose book will be published by Coward, McCann & Geoghegan.

The first time she sat down with a major political figure and felt comfortable as a peer was with Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. She had a complaint. (Before the newspaper she was working with the Board of Child Welfare.) “Everybody was scared to tell him what needed to be done, so I went in and told him.” The next mayor, William O’Dwyer, used to refer to Dolly as Cleopatra.

Mayors were always small time for the granddaughter of Jacob Schiff, a man who had dined with queens and emperors, but Dolly did have an anxiety attack on meeting her first President.

Dolly and F.D.R. met by the swimming pool at Hyde Park in 1936. “My tongue clove to the roof of my mouth. He talked a lot. Once he said to me, driving in his specially built Ford car, ‘What’s the matter, has the cat got your tongue?’ I don’t think I would have been so impressed if George [her second husband, George Backer] hadn’t been so overwhelmed. Also, I was told not to talk about the two things everybody wanted to hear about: war and politics.” Dolly did not break the rules, but F.D.R. did when the spirit moved him … “and I listened.”

The Dolly-and-Nixon transcript was made in 1961 following a long lunch. The most significant impact of that meeting, Mrs. Schiff recalls, was the unguarded admiration Richard Nixon expressed for rich men and for strong men around the world, no matter what their politics. Both of them had just read William Shirer’s book, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Nixon told Dolly he thought there were certain times when one should lie in a campaign for reasons of national security, and expressed admiration for Hitler in one sphere—the way he organized the youth. “I thought Nixon was a very interesting man,” Dolly explains, definitive as fog.

The Temptress…

Last summer Scheherazade met her match. Surrounded by her usual lion’s share of engaging men at a party given by Joseph Kraft, the political columnist, and his wife, Polly, Dolly zeroed in on the newest face: Felix Rohatyn. Her questions at their first meeting had established that he was not only an investment banker, but the Halley’s Comet of Wall Street, the merger and acquisitions star of Lazard Freres & Co., a member of the I.T.T. board, and one of the saviors of the New York Stock Exchange, affluent but old-blue-shirt off-beat, shrewd but flirtatious, and was he married? Separated, he said.

Dolly eventually asked him The Question:

“Do you think I should sell The Post?”

“Of course not,” replied the master negotiator. “That would be like selling your sex glands.”

As always unconscious of any personal attractiveness, she perceives her power of seduction as no more than the seduction of power.

The simile could not be more apropos. It is these two persons, the love partner and the professional contributor, whom Dorothy Schiff has spent her years trying to integrate under one skin.

“Unforeseen problems always arise in my marriages,” she told me one afternoon. “Maybe very common problems, but they always take me by surprise.”

What sort of problems?

“That the other person has needs…”

And so today, as always unconscious of any personal attractiveness, she perceives her power of seduction as no more than the seduction of power. Admiring men express a different view.

Rohatyn, for example, says: “She thinks I take her to dinner because I want to buy The Post, but that’s not true. Dolly is one of the most erotic women I know.”

She says, and this is the amazing fissure behind the papier-mâché mask of both tyrant and temptress: “I always think of myself as a female—at the mercy of men. Whether it’s an advertiser, boyfriend, employee, or executive, all of them. Men would probably say the opposite, but I never think of it that way.”

With that perspective in mind, let the record reflect her triumph as The Professional Rival…

Not a year has passed, in the 34 since Dolly Schiff acquired The Post, without the armchair intellectuals ranting about her soap opera journalism and raving because she refuses to publish an afternoon replica of The New York Times (which they still haven’t finished reading by the time her tabloid hits the stands). Nor has a year passed without a husband, relative, or adviser pronouncing The Post a terminal case and expounding a formula for saving the swan queen’s neck. It comes as a shock to those who think they are humoring a dither-head to discover that Dolly has guts of steel.

George Backer, the husband for whom she acquired The Post in 1939, tried to run the paper single-handedly for two years. He went to the office and wrestled with the deficits while Mrs. Backer stayed at home writing six-figure checks each month. Deficits went up and circulation did not. Mrs. Backer insisted The Post had to change. The paper’s pseudo-Nation pretensions were all very well for impressing her husband’s political friends and croquet partners—“it’s very dangerous for a publisher to have friends,” she warned—but Dolly believed that solvency lay only in slaking the thirsts of the common straphanger and his cloth-coated wife. Not for them harder international news, but more magical thinking: horoscopes, love advisers, gossip, and obits. “And most important, gambling—Wall Street and sports,” she adds today, “[neither] of which one knows when one takes over as a liberal woman publisher.

“I didn’t go to the Harvard Business School—I just improvise day by day.”

“We must popularize the paper,” Dolly insisted in 1942. Vulgarize it, corrected Backer, who by then

thought the paper hopeless anyway. Well then, she would take over. In that case, he would leave the apartment, the paper, everything; he was not about to be married to a career woman. As a parting shot, George Backer told Dolly what he thought her paper was worth:

“Throw it in the East River.”

Another hard-nosed directive came from her brother, John Schiff, the sibling chosen to attend Yale and Oxford and to perpetuate the dynasty. John Schiff is senior partner of Kuhn, Loeb, the family investment bank where the young Dorothy was once refused a clerical job. He told his sister to decide at the outset exactly how much money she would sink into The Post, and then to stop. His formula reflected his very different perspective as a grass-court Long Island gentleman and member of its most rarefied Anglo-Saxon sporting clubs. As Dolly recalls, “John saw the paper as like having a racing stable.”

But Dolly’s was not a spirit to be broken by budgets. “I never think about budgets,” she boasts. “I didn’t go to the Harvard Business School—I just improvise day by day.” The war conveniently took her brother out of the country so that she could ignore his advice. For rich kids this is tantamount to anarchy; it is their historical burden not to blow the family fortune. John Hay Whitney, for instance, later behaved in keeping with his caste. Setting a limit of five years on his unrequited support of The Herald Tribune (it turned out to be close to eight years), he finally succumbed to the brooding of his financial partners in Whitney Communications—men who could pass through losses as a finger through flame, but who went up in smoke over the $3-million annual deficit. Jock Whitney gave up with his paper what was said to be the happiest period of his life. By contrast, Dolly Schiff spent ten years stubbornly pumping millions into her losing investment. In 1949 she could take a few moments out to crow: for the first time The Post was out of the woods.

Dolly works at being a dame. And being a dame works for her.

By the fifties she was no longer suspect as a dilettante. For the first and last time, she even paid herself $50,000 one year “just to feel I could earn a salary.” Then came the blunt phone call welcoming her into the executive locker room of afternoon publishers. It was Roy Howard, then a partner in the Scripps-Howard chain which published The World-Telegram in New York. “You have the Jews, we have the Protestants, and The Journal-American has the Catholics,” he blurted. “Let’s keep it that way.” Which was fine with Dolly, but was not to be the karma of her competitors.

Hard times hit all eight greater metropolitan dailies in the sixties. The publishers pulled together like a small Etonian soccer team to battle Bert Powers, his typographer’s union, and a four-month strike.

“All the men were team players,” decided the owner of The Post as she surveyed the Publishers’ Committee. Dorothy Schiff has never for a millisecond thought of herself as a team player. For three months she played by the men’s rules and one morning she blew up and walked out. No one flinched—this is the baffling part. Not only did Dolly escape the wrath of the other publishers, but none of them broke ranks to compete with her. The Post sailed back into print in the lucrative strike vacuum and its renegade publisher had New York to herself.

What she did not expect was the subsequent merger into The World Journal Tribune. For the first time Dorothy Schiff thought she was licked. “Here were these three big boys getting together—Hearst, Scripps-Howard, and Whitney—to compete in our little evening field. I was petrified.” But Dolly’s luck held. When the W.J.T. folded, she picked up a fistful of columns and went home with a big circulation boost for The Post.

“I’ve never thought of myself as being in competition with men.”

She says it with a naked blue stare. Before one can flinch at the apparent absurdity, Dolly offers her own intriguing theory to explain why she was excused for breaking out of the club, and why the big boys didn’t chew her up just to prove who was top dog: “I think the other publishers, the ones who gave up, would have been furious if I hadn’t been a woman. I wonder if they would have left the evening field open to another man. It’s probably crazy….”, but perhaps it isn’t. Dolly works at being a dame. And being a dame works for her.

“Dolly always makes the unorthodox move,” says mediator Ted Kheel, “which usually turns out to be right for her.” Though he agrees she acted in The Post’s best interests by breaking ranks in 1963, Kheel says the other publishers privately called her every name in the book.

By 1967 the empirical evidence was in. Dolly’s Post remains today the sole survivor in an afternoon graveyard where the bones of Marshall Field’s PM rattle beneath the remains of creations from Hearst, Scripps-Howard, and John Hay Whitney. The same Jock Whitney, that is, who nearly 50 years before was too eligible to be bothered joining the fortune hunters at Dolly’s debutante party.

One of my dreams way back … we used to go and see musical comedies … there would be a terrific dancer or actress who danced down the steps and then the chorus boys would come out. She’d twirl around and go from this one to that one, down the line, and then the leading man would catch her. I’d love to have been her.

Great grave and silent rooms, a forbidden private elevator … a little girl quarantined in the purified ozonosphere of an upper Fifth Avenue nursery, attended by tutors but unexposed to school until she was ten—for fear she’d meet germy children, Mother said—and then her parents would be off again to a formal party, for she saw them only at Sunday lunch, taking suppers in the hush of wealth until her sixteenth year, with only a French-speaking governess for a friend, imagining herself adopted, reading books and spinning fantasies on the vapors and shadows of loneliness … this was the stuff of which Dorothy’s girlhood was made. The dreams of Dolly Schiff, conflicting images which played havoc with her life for its first 50 years, were fashioned from this thinness of air.

She yearned to be grown-up all the time she was a child, to try everything, to be sophisticated, to make a contribution. The surrounding forces conspired to keep her dependent, physically, financially, and emotionally. Mademoiselle, her governess, literally steered a dangling Dolly across streets. Her mother was very strict and her father a tease.

“Nobody ever said anything nice to me,” she recalls. “I was always being told what was wrong with me and compared unfavorably with other girls.” The other girls had allowances; she was not to be spoiled. When they dallied in the drugstore, her best friend used to say, “For God’s sake, Dolly, buy something!” But when she told her mother about the other girls and their allowances, Adèle Neustadt Schiff said coldly, “If you need anything, tell me. I’ll get it for you.” These early cripplings are still being played out in Dolly’s physical fears of flying and driving, her inability to praise, her frozen capacity to ask people for help. Advice, yes. Help, never.

Fat as a youngster, and terribly awkward, she was force-fed every kind of lesson: tennis, golf, and especially riding, because her father kept horses as a rebellion against the piety of his father. “It was so boring,” she explodes in a frustration reminiscent of Margaret Mead. Her earliest dream was a clear reflection of Grandpa Schiff’s dynamic model as a philanthropist. “I wanted to do something useful.”

War work made the greatest impact on her early teens. Mademoiselle had relatives at the front and Dolly worried with her about them. For four years Dolly’s idealism was absorbed in a canning kitchen. She found there her first strong role model, a Christian Scientist socialite, on whom she developed a crush. And she delighted in being terribly busy.

“Then the war was over and it stopped. I felt very useless.”

The Christian Scientist committed suicide.

To write fiction, that was the next dream. She was challenged by her English teacher at Brearley, a Miss Allington: “What do you want to write about?”

“A girl in boarding school,” Dolly said.

Miss Allington’s answer was “You can’t because you don’t know what it’s like to be a girl in boarding school, since you’ve never been to boarding school.” And so Dolly gave up.

Some years later, Miss Allington committed suicide.

When her parents finally relented and released her to Bryn Mawr for a year, she latched onto a missionary from Labrador. She begged to follow him, but Mother was horrified. “I was looking for an occupation, I suppose,” Dolly recounts wistfully. “I wanted to contribute.”

Discouraged on all substantial fronts, Dolly capitulated to the number one priority of her time and status: to be popular and marriageable. One of the girls she most admired was in great demand. Beatrice Byrne, a couple of years her senior, danced so beautifully that all the boys cut in on her. The other belle she idolized was Peggy Thayer, very proud, very Main Line Philadelphia, who married Harold Talbott, a dashing self-made commoner in the automobile industry. But Talbott was later disgraced in the Eisenhower Administration and subsequently died.

Dolly at eighteen had but one vision: “I wanted to marry a man I was terrifically in love with and have eight children.”

Beatrice Byrne committed suicide before her twenty-first year. Dolly’s recollection is condensed with its pain: “Over a man. She jumped off a bridge in Switzerland. A no-good Englishman.” And then, after a reverie about the extraordinary attractiveness of Peggy Talbott … “she jumped out of her window on Fifth Avenue in the middle of the summer, not so long ago.” It was only recently, while Mrs. Schiff and I were talking about the pivotal women after whom she tried to model herself, that this morbid refrain became apparent. From a slow stun her reaction emerged: “I envied them and thought they were so glamorous. But now I can see I was better off being me.”

Bryn Mawr opened to her a world as romantic and risqué as a musical comedy costume box. She had never met anyone who didn’t live on the Upper East Side. Suddenly thrown together with contemporaries from all over the country, she would sit up all night drinking a thick cocoa called “muddle,” devouring the stories and love letters offered by the Southern girls. “I was absolutely fascinated, learning about life and sex.”

The coquettes tried in vain to teach her “the look,” but making eyes like a sick dog disgusted her. She never got the hang of flirting, though the girls later told her she was sexy in her own mysterious way. Did she play dumb?

“I was never that devious,” acknowledges the Dolly of today. “I think I was dumb!”

Her parents reinforced the suspicion. The deal was that she could only mark time at Bryn Mawr for a year before she was old enough to make her debut. So completely did her romantic fantasies overwhelm the heiress of Jacob Schiff, who had died the year before her debut, that no one could warn her to beware of fortune hunters. She didn’t understand that the point of debutante parties was to be presented to eligible men. Determined to foil the dull and proper marriage that was the fate of her forebears, and to escape the isolation of her childhood, Dolly at eighteen had but one vision: “I wanted to marry a man I was terrifically in love with and have eight children.”

Her eye fell on the smoothest dancer, the most coveted extra man, the snooty figure of Dick Hall, who described himself as “a gentleman of leisure.” In truth, he had not a sou. This was heresy within family parlors of Our Crowd. The Schiffs exhausted themselves propelling their daughter back and forth across the Atlantic for two years, until, as their final coup, they brought a Rothschild over from France. (The measure of their desperation was the generations of pedigree rivalry that stood between the Schiffs and the Rothschilds; the Schiffs claimed the longest continuous record of any Jewish family in existence, cum rabbis and scholars, not just moguls.) “He was repulsive,” says Dolly of her Rothschild suitor. “And not only that, he came with his mistress.”

Dolly’s will prevailed. She married Dick Hall. Her dream burst within a year. In those days the only form of birth control known to her set, though unreliable and dangerous, was douching with Lysol. The boys knew about condoms, but few self-respecting husbands would use them. So it was Dolly’s lot to deliver her first baby exactly nine months and four days after her wedding.

The fatal flaw was revealed following a tea dance at Sherry’s on Park Avenue. Dolly was bulging with the first child. Driving home, her husband carped mercilessly, “You know, I’m the only person who asked you to dance.” Shocked by his observation (she hadn’t noticed), Dolly resolved aloud, “Dick, once I’ve had this baby, you’ll never be able to say that again.” For further emphasis, she put him on notice that she would thereafter take two drinks for every one of his. “Well, I drank plenty,” she recalls.

In 1925 she had a second child, Adele, thirteen months after her son, Mortimer. Her life took on the tinny glamour of Prohibition, lots of night-clubbing and two-dollar drugstore gin, then coming home to a two-bedroom apartment with a depressing quantity of diapers hung to dry.

“I was just like a child in my mother’s house. And I was utterly dependent on my father, financially. I had no money until my parents died.”

“Those were the Palm Beach days and there was a lot of what we called whoopee in Florida,” Mrs. Schiff recounts. “Dick and I started going separate ways. There was really no function for me. I had a nurse for the children and later a Swiss governess whom everyone thought was great. I had the apartment in New York, but during the summers I took the children to live with my parents in Oyster Bay.”

Obsessed with the nuances of proper entertaining and décor and abundantly supplied with servants, Dolly’s mother ran her house with the precision of a German timepiece. There was nothing for Dolly to do but play around. “I was just like a child in my mother’s house. And I was utterly dependent on my father, financially. I had no money until my parents died.”

Despairing, Dorothy approached her father with her desire for a divorce. A man dominated and severely disciplined by, yet never able to please, his own father, Mortimer Schiff père decreed that divorce was out of the question. Then he died suddenly in 1931, leaving Dorothy’s husband a substantial amount of money. (Schiff had taken the idea from Payne Whitney, who had left enough money to his son-in-law, Charles Payson, to ensure he wouldn’t be too dependent on Whitney’s daughter, Joan.) Before Dolly could begin the severing of her marriage, her mother developed a terminal illness which kept things static for one more year. But financial dependence would never bind her again. Mortimer Schiff had left an estate worth well over $20 million, and this was in the Depression.

Dolly’s second and lifelong plan evolved over the summer of her twenty-eighth year. She came under the spell of another kind of lord in a different sort of realm from the rigid kingdom of Jacob Schiff’s Wall Street. Max Beaverbrook, press lord of England, aspiring prime minister and keeper of the most dazzling political salon in London, became Dolly’s Pygmalion. He was 52, only two years younger than her father, but unlike any man she had ever known.

A buffalo-headed cad with an outrageous ego, malicious, faithless, and easily bored: Beaverbrook was all those things, but never dull—one of those men whose ambition is charged with such vulgar energy as to make them magnetic. He began by selling newspapers for pocket money when he was twelve, made a fortune in business ventures, and had ascended to a baronetcy and purchased his first newspaper by the time he was 38. Six years later, he controlled three of London’s major newspapers, and used them to expound his conservative political views. He was a self-made man, and he liked to mold others. The delicious thing about that Beaverbrook summer for the unformed princess who was the upstairs guest, was that all the other women, including his mistress, the Honorable Mrs. Richard Norton, were summering in the south of France. All the young belles of Europe hated Dolly, she boasts. They were certain she had her cap set for Beaverbrook.

“It was the most terrific summer of my life, because there was no competition. There would often be twelve men and me.” Twelve men and Dolly … what a breathtaking saraband to her meager fantasy of twirling down a line of chorus boys as a dancer in a Broadway musical. And here at Stornoway House, resplendent in evening clothes, her partners were men like H. G. Wells and political leaders of all parties.

The first dinner party at Beaverbrook’s was a scandal. The tycoon had a complex about women being after nothing but his money. Dorothy Schiff intrigued him as a recent heiress. The estate had not been settled.

“Are you as rich as Doris Duke?” he demanded to know. When Dolly said she hadn’t the faintest, he bellowed for his secretary: “Get out the Mortimer Schiff will!” Glorying in his vulgarity, Lord Beaverbrook read the document aloud at the table before even the king’s physician. For Beaverbrook’s outrageous behavior the king’s doctor offered an apology, but it was lost on Dorothy.

“I wanted to know what was in the will myself.” (She was left $750,000 outright, the house in Palm Beach, a third of the thousand acres in Oyster Bay, and one-fifth of the residuary estate. Her mother inherited three-fifths; her brother John one-fifth, plus a fabulous art and book collection and the family house on Fifth Avenue.)

With that escapade for openers, Beaverbrook, wearing evening clothes, traipsed Dolly through his seldom visited Express plant. But it was about politics and not newspapers that she learned from her guide. Elections were coming up in England that fall and Beaverbrook was making speeches for the Conservative Party. “The English women who were around knew a great deal about politics,” Dolly remembers. “I knew nothing. One of them asked me how we managed to operate on three levels of government in America, and I didn’t know what she meant.” Beaverbrook turned down an invitation from Venetia Montagu, a celebrated wit of the time, because his protégée wasn’t ready yet. “She’ll make a fool of you,” he warned.

Dolly and Lord Max discussed marriage. He summarily dismissed Dick Hall. “Get rid of him. That isn’t for you.” She was terrifically in love with Max, but the age difference created jealousies on both sides.

“I always wished I had been trained as a social worker or a reporter. I longed to have a profession instead of always being Mrs. Moneybags.”

Reality intruded that fall. Dolly became again Mrs. Hall with children who had to be shepherded back to school. Beaverbrook did not want her to leave. Like all Pygmalions, he was unaccustomed to having his Galatea say no.

“I think I lost him when I left. But I didn’t know I’d lost him until later.” She was obsessed with Beaverbrook for twenty years.

At 29, Dolly was in deep trouble. “My mother was dying and the thing with Max was not working out.” She got her divorce and married a sympathetic man before the year of her mother’s death was out. George Backer was his name, another attractive leisured gentleman of no immediate financial substance, but with a peripheral connection to politics and a group of interesting friends, including the Algonquin set. They provided Dolly an orbit to make up for the lost world of Beaverbrook.

The great impulse to break into a wider world felt by most women at 30 was there for Dolly. But it was frozen by the slow-acting anesthetics of noblesse oblige, marital compromise, and another pregnancy. She was straining to be active in politics. Through her association with Backer, a former speechwriter for Mayor Jimmy Walker, she switched her registration to become a Democrat.

As an orphaned daughter who bore a recognized family fortune, she was still obliged to endure endless charity meetings, boring ladies’ lunches at the Colony Restaurant and to lend her name to boards.

“I was on all of these committees, but it was always fund-raising,” Dorothy Schiff laments. “I always wished I had been trained as a social worker or a reporter. I longed to have a profession instead of always being Mrs. Moneybags.”

The birth of her daughter, Sarah Ann, triggered a classic post-partum depression in the 31-year-old Dorothy Backer. She sought out Harry Stack Sullivan, the famous psychoanalyst, and clung to him five days a week for the next two years.

She left her analyst the day she overcame her paralyzing shyness in public and made a national radio address for F.D.R.’s 1936 Presidential campaign. Sullivan hadn’t listened. “By then I was thoroughly in politics and terribly busy again. I had a function. I belonged to a group of like-thinking people. It’s so important.”

At 35 she was still not happy. Nothing measured up to the fun and stimulation of that Beaverbrook summer. She returned to London for a summer with her husband, but as Mrs. Backer it was a big disappointment. “I wasn’t the only woman at Max Beaverbrook’s parties. George had a marvelous time.”

It is tempting to speculate that Mrs. Backer acquired The Post for Mr. Backer in order to rekindle and live out the dream sparked by Beaverbrook, doing by herself what she couldn’t do with Lord Max. Her great moment came two years after the purchase.

Captain Joseph Patterson, founder of The Daily News, staged a large dinner at the River Club for Lord Beaverbrook. All the New York publishers were invited, among whom Dolly was the newest. And so she was seated in Siberia, at Table Ten, while Lord Max, Captain Patterson and company blithely celebrated at Table One. Dolly picked disconsolately at her dinner—until she was tapped on the shoulder by her friend, Alicia Patterson, the host’s daughter.

“Lord Beaverbrook has spotted you,” Alicia whispered. “He’s very anxious to talk to you. Will you change places with me?” Everybody’s eyes popped as Dolly Schiff took her place beside Lord Max. As she weaves the tale today, it is the high color in her childhood fantasy of the dancing lady with multiple partners in white tie and tails … she’d twirl around and go from this one to that one, down the line, and then the leading man would catch her.

Shortly after that magic night, Dolly Schiff found her occupation at last. She was 38 before she acted on her long-diverted impulse to contribute, slipped into the sleeves of her publisher coat, and actively succeeded her husband as president of The Post.

The parallels with her grandfather are striking. Jacob Schiff never saw eye to eye with his partner by marriage, Solomon Loeb. Loeb, like Backer, was temperate; Jacob, like Dolly, was bold. He wanted a bank of his own, and his will was done. Dolly wanted a paper of her own, but, unlike Grandpa Schiff, who for all his philanthropy was too “buttoned up” to have the common touch, Dolly was a natural purveyor of popular taste. And by then, “somebody new had come into my life with a lot of good ideas.”

Dolly Schiff’s life took on the developmental pattern of a man’s. She made a life among men, suffered the marital problems of a husband, and enjoyed the influence of a power lord.

Ted Thackrey had come out of the west like the Chinook wind, a successful young editor, to become feature editor of The Post. In a Herald Tribune profile he read that Dolly wanted to write a column. He called her up and began the power game. “If you’re going to write a column,” he said, emphasizing his authority, “I think you ought to talk to the feature editor.”

“I got to know Ted Thackrey and I started listening to him. He was very interested in changing the paper. More than in my writing a column. He thought he’d get at George; everybody thought George owned the paper.” Dolly thought Thackrey’s ideas were good, he happened to cross her life at the moment when she was ready to claim her dominion. When Pearl Harbor broke, Dolly and Ted put the paper to bed while George remained uptown writing editorials.

After this critical juncture, Dolly Schiff’s life took on the developmental pattern of a man’s. She made a life among men, suffered the marital problems of a husband, and enjoyed the influence of a power lord. Her old conservative friends began to drop away from the New Deal Democrat and a busy life separated her from the rest. She and George Backer were divorced.

One afternoon in 1943, she went to work in a gray silk dress and married Ted Thackrey. In her office. Justice Samuel Rosenman presided; a few friends and whichever children were in town attended. Why the office? “Because it was an office romance.” The newlyweds spent the night in a hotel and went back to work in adjoining offices the next day and—trouble. Ted insisted on being co-publisher. She said, “Okay, then I’ll be co-editor.” The titles were changed. But the central conflict of Dorothy Schiff’s life, and perhaps the greatest dilemma of womankind—the desire to be devoted to one man, colliding with the unrelenting need to be of purpose in the world—had spun out of control.

For Dolly, the collision with Thackrey was played out over a 1948 political endorsement. Thackrey wrote a column called “Appeal to Reason,” supporting Henry Wallace. Opposed to Wallace and cool to Harry Truman, Dolly answered with an editorial endorsing Thomas Dewey. “It’s printable,” her husband growled and answered back in print. From a joint apartment but separate offices, their published volleys went on and on.

Ted grew bitter. While Dolly idealized him as a writer and reformer, she did not recognize his jealousy. “He was a very ambitious guy. I guess I didn’t understand that. He really wanted to own his own newspaper.”

As the giants rumbled above, the city room grunts cast fearful eyes at the ceiling. After Truman—the man neither wanted—was elected President, Dolly left the situation unresolved and sailed off with Alicia Patterson for a U.N. session in Paris.

Alicia was an influence on Dolly. She became a publisher a year after Mrs. Schiff acquired control of The Post, and they supported each other in the treacherous waters a woman owner must wade through. Burning to inherit Captain Patterson’s Daily News, Alicia had started Newsday as a little country chronicle to prove to her father she could handle a newspaper. Her dream failed, but Dolly always admired her journalistic courage—“She would print anything”—and recalls a series on homosexuality that Newsday ran back in the forties. Alicia once included her in an intrepid interview at Frank Costello’s home in Sands Point, about which Dolly penned a lively column. And so, on their voyage to Europe following the Thackrey explosion, Dolly listened carefully to Alicia’s opinion. She said, “No member of the working press has ever been given the break you’ve given to Ted Thackrey.” Dolly had never thought of that.

A month later, unpredictable as always, she gave control of the paper to Ted Thackrey for Christmas.

“I fled to California. The problems were so overwhelming with Ted, the paper, everything. It seemed a way out, to let him try it alone, which is what he had always wanted.”

Did she believe he would fail? asked Mrs. Schiff recently.

“Yes, I think I knew he would.”

Three months passed during which The Post’s quality retail advertisers fell away. Thackrey left with a following of firebrand writers to start his own paper, The Compass, which also failed. Dorothy Schiff returned to her Post to pick up the pieces and in no time had her advertisers back. Resuming her maiden name, she has been sole publisher ever since, and in 1962 became editor-in-chief.

At her half-century mark, Dorothy Schiff was still not convinced her two dreams were incompatible. She gave marriage one more try. Her confidante, Alicia Patterson, had only to meet Rudolf Sonneborn, a 55-year-old liberal industrialist from Baltimore, to counsel, “Don’t let this slip through your fingers.” When Sonneborn followed her to California to announce he had divorce papers in hand and a doctor coming for blood tests, Dolly was petrified. She sent for her son, took a few deep breaths, and married Sonneborn on the spot.

“He was very proud of me and he didn’t mind being introduced as Mr. Schiff. Rudolf was as secure a man as I could have found.” In retrospect, Dolly’s regrets about this marriage center on her own failings. “I was too busy with the paper to give him the kind of attention he deserved.”

Awed by the way she moved in the world of presidents and governors, Dolly’s mates always wanted to get into the act. Sonneborn, for all his apparent security, was not the exception. Dolly was not interested in business trips to Rudolf’s refineries. And he, like all of her previous husbands, could not resist poaching on her more glamorous estate.

I thought that I was in a dream. We met in many hotels, many clubs … always in separate rooms. It was like a play … there were so many echelons, labor leaders, presidents of the union. Pierre Salinger came up, and Secretary of Labor Willard Wirtz … it was terrific, fabulous!

Dorothy Schiff’s reverie describes one of her life’s greatest dramas. As a member of the Publishers’ Committee during the 1963 newspaper strike, she was a star in a play that ran in New York every day and night for three months, with an otherwise all-male cast.

“It’s 28 men and me. The only trouble is my maid keeps worrying that I haven’t enough clean things to wear.”

Dolly kept stepping outside the curtain to study the characters and changes of sets and scene. At the opening she ignorantly went to dinner in a Chinese restaurant with the industrial relations manager of The Herald Tribune, a bit player. She was scolded for dining down by Walter Thayer, that paper’s key representative, “so after that, I always had dinner with the publishers”: Jack Flynn for The Daily News, Amory Bradford and Orvil Dryfoos for The Times (“Orvil was the publisher’s son-in-law but a very nice person—he’d always run out and get sandwiches”), Walter Thayer for The Herald Tribune, Jack Howard for The World-Telegram, Richard Berlin for Hearst, Charles McCabe for The Mirror, and Theodore Newhouse for The Long Island Press.

“Part of their act was to keep you seduced, keep you in the club. So they gave you a lot of attention.” It must have been like a three-month Beaverbrook dinner party. She moved out of her apartment and into the Pierre Hotel, with a Chanel-style suit and a dress. She thought it would be over in a few days. Nora Ephron, who wrote for The Post at the time, recalls Mrs. Schiff saying: “It’s 28 men and me. The only trouble is my maid keeps worrying that I haven’t enough clean things to wear.”

She had no idea she would stage the walk-out until it happened. She certainly didn’t discuss it with her counsel. Her appeals to have him added to negotiating subcommittees had been continually voted down. The night before, she had been at an inconclusive meeting at Gracie Mansion with Mayor Wagner. “I had made such a fuss about not being included in an earlier meeting, they gave up and took me along.” But the next morning another vote ruled against labor counsel representation for The Post in a negotiating session.

“It was almost like a madness, a fit of temper,” she remembers of her climactic exit. Dorothy Schiff rose, swept up her handbag with its list of critical phone numbers, announced calmly “I hereby resign from the Publishers’ Association and I’m going to call Bertram Powers,” and departed the duchess.

Before she could dial, The Times’s Orvil Dryfoos was pounding on the phone booth door. He implored Dolly to find out what Powers would settle for before she told him about her resignation. “Of course, this had been the name of the game for three months.”

After many a season of harking to her tale and marking her ways, I asked Scheherazade the answer to the riddle.

Can a powerful woman have a satisfying private life?

“I made my choice,” she said evenly. “I’m willing to give up one thing for the other. I’d like to have both, but that I haven’t been able to do. When I’m away from The Post, I don’t feel myself.”

This decision was made after she passed 50.

“I think weekends and vacations it would be nice to have the other thing [marriage], but then what do you do with them the rest of the time? They get in your hair.”

Power was not thrust on Dorothy Schiff, as it was on Katharine Graham when she took over as publisher of The Washington Post after her husband died.

“Kay always said she was a mouse while she was married,” Dolly says thoughtfully. “I don’t think I was ever a mouse.” But today the two women must wrestle with the same riddle. Powerful women can have only a consort or affairs. Yet both are unsuitable choices. Dorothy Schiff shares the view that consorts rarely work out. “I wouldn’t mind having a consort like Prince Phillip,” but she says she has never thought it through. Men as friends are something else, however, very much to be cultivated. But husbands?

“I think weekends and vacations it would be nice to have the other thing [marriage], but then what do you do with them the rest of the time? They get in your hair.” One vision she cannot forget is that of Frank McCormick, husband of The Times’s political columnist, Anne O’Hare McCormick… “a little man standing back of her, holding her coat, and looking perfectly happy. But that useful kind of man has never appealed to me.”

A Beaverbrook reprise took place shortly before her final marriage to Rudolf Sonneborn. The press lord read of her arrival in the London papers. He phoned to invite her to a party. Excited, she asked if she could bring someone. Her former mentor sounded surprised. “Rudolf handled himself very well that evening. And then I was over it, exactly twenty years later.” She knows now she could never have managed a man so demanding as Beaverbrook.

In her early sixties she was separated from her fourth husband. Sonneborn was by then a semi-invalid, having suffered a massive stroke six years after they married. She settled into her skin with a new perception, becoming more exclusive, less inhibited, and more content to be her own woman. “When I was a child, my best friends were four years older. Then I went through a period when the men were twenty years older than I. But as I grow older, the men get to be younger.” Many invitations she might once have accepted have become nuisance dates. The isolation of her childhood has fortified her later years. She is quite able to amuse herself.

I asked her whether or not her sensuality has been inhibited since the world began viewing her as an older woman.”

“Yes, I have resisted more than once,” smiled Scheherazade, at 70. “And then I thought, it’s silly—if the occasion should arise again between two consenting adults, I should relax and enjoy it.”

Dolly makes a convincing case for the pleasures of being older.

“One becomes a sort of Mary Worth figure. A lot of men want to talk to you and tell you their problems. And I love to be taken out to dinner.”

How much tidier an evening is now. She is not expected to stay up all night, an escort can be asked to take her home in time to read the early editions of the morning papers. “Another compensation,” she observes, “is that other women are no longer jealous of me.” This seemed to me to be one of those misperceptions common to people who are so unique as to forget the distance between themselves and ordinary folk.

Few men, and almost no women, can wake up at the age of 70 to the drumbeat of Dorothy Schiff’s days. “What do you know?” is her customary greeting to the first caller of the day. “Have you read—————?” will come up several beats later, and she will fill in with the title of the political book she devoured over the weekend or a provocative columnist’s point of view from Some Other Paper. These are scarcely flibbertigibbet questions from a retired gin rummy player. This is a publisher’s pulse. And far more compelling even than the undimmable blue highbeams that are Dolly Schiff’s eyes, or her languid legs and hypnotic mannerisms, is the magnetism that is every day recharged by her involvement in affairs of the world.

After reading and marking the morning papers, she can scarcely wait for The Post’s first edition to be delivered before she is on the fly to the office. People ask why she has no phone in her car. Answer: she is too busy chewing over the papers and last night’s talk shows with her chauffeur. Six days a week she spends intense minutes on the phone with Editorial Page Editor Wechsler taking apart the day’s issues: Suppose impeachment results in Nixon’s exoneration? Who on the Cost of Living Council really held up settlement of the municipal hospital strike? Who would Gerald Ford pick as his vice president?

Before any afternoon is out, then, Dolly Schiff will have ingested the news, polled her sources, conferred with her editors, and put her views before 680,565 readers. That is power.

On Saturday she will grit her teeth and shop, or sometimes entertain. Only the most utilitarian menus suit her. If she hits on a decent chicken curry and a California Chablis, so be it for three dinners in a row. Anything more elaborate and, as the veteran wife says, “I’d be right back to the housekeeping problems.” Besides, the point is always the same: to bring together people with something provocative to say.

Sunday is a working day. Lunch is never before three. She reads The Times early and well, as if cramming for a civics exam, before turning to the tube for the midday news-interviews shows. Then Wechsler again. Both of them work like lightning, trading that brand of gaping non sequiturs common only among professional journalists and institutionalized schizophrenics.

Before any afternoon is out, then, Dolly Schiff will have ingested the news, polled her sources, conferred with her editors, and put her views before 680,565 readers. That is power. Not the kind of false-bottom power to which the wives of politicians and top management cling, and in which they can find only a most treacherous source of self-esteem. A woman who has decided to live herself out through her husband’s ambitions is always in danger of losing his dream. And when he is threatened, it is she who flies out of control. Mrs. Schiff has also noted this phenomenon. “It’s not the politicians or tycoons who get mad at you [a publisher], it’s the wives. For instance Marie Harriman, when I switched from Averell [Harriman, then a candidate for governor] to support Rockefeller in 1958, didn’t speak to me for a long time.” And for good reason: Mrs. Schiff’s last-minute switch is credited with swinging the narrow election that made Nelson Rockefeller a governor.

Money alone could not have bought the self-esteem Dorothy Schiff thrives on today. The women she idolized as a child had pots of money. What distinguished them from men was not so much their gender as their fear or their failure to complete themselves, to be useful, to exercise power. They paid for such fear with their lives.

To dare to hold power exacted its own price in Dolly Schiff’s generation. She paid with rocky marriages, perhaps largely because there were no models from which to learn and no support from society for what seemed a disturbingly unorthodox life pattern.

With its strength and its flaws, this Scheherazade has left us some 12,401 nights of exuberant living to ponder. And she is nowhere near finished spinning her tale. For Dorothy Schiff has five editions to fill tomorrow. And tomorrow and tomorrow.