His reputation as the guru of magazine writing preceded him so it came as a surprise that Jay Lovinger not only lived a couple of blocks from me in Riverdale but that he was indistinguishable from the other guys lolling around Johnson avenue. We met at Starbucks. Jay wore a faded sweatshirt with the print of a giant lion’s head on the front that had the kind of lo-fi charm once reserved for black velvet paintings. His glasses were foggy and he chuckled when he said, “They call me the Yoda of magazine writing.”

“Well, are you?”

Jay chuckled again. “Yes, I guess I am.”

A few years later I interviewed Jay a handful of times for an oral history on Inside Sports, the Washington Post’s short-lived attempt at a monthly sports magazine, where Jay got his first big break. He was good company, candid, and unpretentious. He introduced me to other people, encouraged the piece, even looked at an early draft in which he was the main character. He appreciated the gesture but thought it was misguided and he was right. Still, I found Jay to be one of the most interesting characters in a group littered with them. And it’s because Jay Lovinger’s talent was helping writers and editors realize their talent. There is a whole transactional process between editor and writer that is invisible, as it should and must be, to everyone but the writer and the editor, and it is here where Jay’s gifts came to life.

Jay’s career took him from Inside Sports to People and The Washington Post, from Life and Sports Illustrated to ESPN, where he had a hand in Page2 and e-Ticket.

Combing through the interviews I did for the oral history I came across some revealing glimpses of Jay—as well as some choice words from the man himself.

Robert Lipsyte: I think a case can be made that Jay Lovinger is the best editor who ever lived.

Richard Ford: His chief ability was to be sympathetic to the writer.

Tony Kornheiser: Jay’s a few years older than I am. Maybe three, I don’t know. Jay was this legendary basketball player and snack bar person at Harpur College—it was not Binghamton then it was Harpur. The school started in the mid-’40s. The only people who went there were people who couldn’t afford Ivy League schools. Occasionally, there’d be a fairly substantial economic person who just didn’t get into an Ivy League school. But at that time it was a very smart school. By far the smartest state institution. The only schools in the state that were better were Cornell and Columbia, that’s it. Nothing else was even close, it was that good.

There was no real outside influences and a lot of the kids were city kids. Jay is from upstate [Jay lived in the Jacob Riis housing projects on 12th street and Avenue D until he was 11 before his family moved upstate to Kerhonkson]. He used to hang out with these guys—we didn’t have fraternities we had social clubs, like teams. We had a team called “Grass” for obvious reasons and Jay was one of those guys. And Jay was a basketball player. Slow but a pretty good shooter.

Jay, 1970s.

I don’t think he ever graduated. He was a gambler. He was a gin player, a poker player. Guy went to the track and stuff like that. The two words I would use are both “w” words: wry and wise. And everybody knew that. It was just obvious. He was one of those obviously smarter, superior—he didn’t act superior—but he was intellectually superior at a school that was extraordinarily middle class, first-generation college people.

Jay was charismatic for a certain type of kid. He was charismatic for an intellectually aspirational kid. But not like science aspirational, like English aspirational. You could talk to Jay. Jay would accept people who were not of his group but who could hang out with him. But you had to be smart, that was the whole thing. And everybody would be afraid of Jay and his group. I considered it a huge victory if Jay Lovinger knew who I was.

I think I’m pretty smart. No, he was way out of my league. Way out of my league. Absolutely. I mean the guys he hung out with they were the druggies, you know, they were the sort of advanced guard of whatever revolution was taking place. I don’t want to call it a social revolution that’s trite and cliché. Really smart, disaffected kids. You’ve watched Annie Hall a thousand times. Jay is the guy who actually gets Marshall McLuhan and shows this asshole what’s really going on. That’s Jay. That’s Jay Lovinger.

“Jay understood on an individual level what every writer needed and got them there. That’s the beauty of editing, isn’t it?”

We worked together once or twice, that’s all. I don’t know what other guys need. I mean, I really don’t. I don’t need much after I start writing. I need the pre-edit, I need the guy to shape the story for me, I need the guy to encourage me because he’ll say, here’s who you talk to, here’s why you talk to them, this is what you’re going to find out, this is what you’re going to see. And you fill in the flourishes because that’s what you’re good at. I’m that guy. I’m the guy they say, “You just keep thinkin’, Butch, that’s what you’re good at.” I’m a follower, I’m not a leader.

And so Jay got me to the pieces. Jay would explain, “This is the vision of the piece, this is the concept of the piece, this is why you can do this, Tony. You can do this, and here’s why.” And that’s what I needed. I don’t know what Gary Smith needs, I don’t know what other people need.

What I’m going to tell you now is, I suspect, the key to Jay Lovinger: Jay understood on an individual level what every writer needed and got them there. That’s the beauty of editing, isn’t it? There are 50 writers out there that he’s worked with that swear by him and each one of them is going to need something different from Jay Lovinger. I believe you’ll find that Jay recognized the strengths and weaknesses from every one of his writers and played away from the weaknesses. That would be my guess.

Let me just say this to you so you hear it, so you know it. I’ve spent my life in newspapers and now television and radio and magazines. And I’ve done them at high levels, extremely high levels. I’ve got like a ridiculous resume: Newsday, the Times, The Washington Post. I’ve written for every great magazine there is and now I’m TV. All right, so I’ve got all this stuff. I’ve got all these credentials: Jay’s the smartest guy I ever worked with.

I’ve worked with really—I cannot emphasize to you enough how smart the people were that very graciously took me under their wings. Pete Bonventre and John Walsh. David Hamilton at Newsday, Shelby Coffey at The Washington Post, Jane Amsterdam at The Washington Post. I’m not even going to people like Bradlee. People I worked directly with, directly for. Really, really smart people. Eric Rydholm at PTI, he’s a genius. He is.

Lovinger is the most gifted intellectually of all of those people and you would not know it to talk to him. I worked with David Remnick closely. Ask Remnick about Lovinger. You’re not going to find anyone whose work you like who will say anything other than, “Lovinger? Oh my God.”

That’s what they’re going to say. All of them are going to say that, right? Please … tell me nobody said anything bad about Jay. When you used the phrase about Jay as a “Yoda” I think that’s really it. If I remember my Star Wars, the thing about Yoda was that you had to seek him out, that he was very quiet, that he imparted wisdom without having to talk and talk and talk. I talk and talk and talk. I’m telling you, Jay was wry and wise.

John Ed Bradley: Ben Bradlee called Jay the best magazine editor in the country. The Post was determined to compete with the New York Times magazine. Tony was always talking about Jay, how great he was. He came in and I just loved him immediately. He was very down to earth, unpretentious, easy to talk to. It was a very competitive environment and I got none of that from him. He knew who he was. He didn’t have to play the game. So immediately, there was trust there. I just responded to the guy. He was an easy guy to love.

He’d sit in his office and he liked to talk out a piece. I never liked to be bothered once I was reporting a story. I didn’t like it when editors asked me what I had. But he had a way of getting that out of you, that kind of talking out a piece ahead of time.

I wrote a feature for the launch issue of the magazine. There’s no way I could write it in the crucible that was the newsroom so I was playing hooky at home writing. There’s a knock on the door and it’s Jay. I let him in and we sat there and we talked. The main thing he did, he settled me down, and somehow he instilled confidence in me. He let me know it was going to be a great piece and everything was going to be fine. He just had a way about him I believed in. I believed in the guy. That was the first time an editor came into my home to talk me through a piece. That never happened again.

“He was really good at helping you find the story. It’s huge and it’s hard to do.”

He always talked about other writers. We always talked about what was out there, who was writing what and what stories did we think were great. There was always this dialogue going on. He was a big reader. He’s read everything. But doesn’t try to impress you with it. He’s not a modest person but there’s no pretention. Some guys will just try to beat you down with their smarts, you know? Or try to nail you in the ground with it. I wasn’t intimidated by him. I was intimidated by others. And not because they were good but because they let you know they weren’t available to you.

Jay just knew how stories work and what made a good story. He knows when to stay away. He knows when you need to find it on your own. He kept the pressure away from you. He’s like the coach who just knows how to handle his quarterback. I never saw him panic. The magazine needed to fly and it was a stressful situation. But I never got from him, the pressure.

I don’t know what his magic is but I think he just understands how damn hard it is to write. I’ve had editors who are great at marking up copy but I remember him as being more of a big picture kind of guy, more of a visionary kind of guy. He could make sense of really complicated situations, he could simplify them. Sometimes we overwork these stories in the reporting. We get so much material, how do we make sense of this? How do we build a story from what we have here? And he was really good at helping you find the story. It’s huge and it’s hard to do.

I’m indebted to Jay. I feel like I owe him something. Because he was just such a—he’s probably not aware of the impact he had on my life and my career. He made me feel that I could play at that level. He wasn’t some legend that you can’t approach or touch or feel. He was real.

Roger Director: He used to love the trotters. He used to go to Monticello Raceway, Yonkers Raceway back in New York. He’d bet on the ponies. And I’m not talking about American Pharoah here I’m talking about the pacers. He was a good handicapper. He looked at the horseflesh. He had kind of an instinct and a feel for who to bet on, how things were going to run, how things were going to turn out.

The world was sort of racing form to him. He had a very particular eye toward looking at a situation and what to look for. He’s very insightful in that way, the way he’s able to survey the field and pick out what to look for and as an editor, he was, in his manner, wonderfully measured.

“Jay opened the doors and windows for me.”

There are some editors who can jostle you when you’re out reporting a story and you’ll sense something in their voice. You’ll sense something’s got them unnerved, something is causing them concern, and they’re not necessarily conveying that you, maybe they’re masking something to you, but you pick up your editor’s tone, the voice, an enormous amount of stuff that may not be contained in the back-and-forth of the conversation about what’s the next step, who do I have to get, who do I have to talk to, where do I have to go? But Jay never had anything less than a very calm, reassuring, confidence in the writers that he was working with and the process that everybody was going through.

Gary Smith: Jay Lovinger was the great golden treasure awaiting me. That’s how I learned that a magazine piece was a whole different feature than a newspaper piece. Jay opened the doors and windows for me, absolutely.

That was a great opportunity to be there and work with Jay closely. I’d turn in a piece and Jay and I would be in his office until three in the morning, all night, just talking about a story. I’d sleep on the sofa there, grab three-four hours of sleep. He’d be willing to be up crazy hours to talk about a piece. He just really opened it up for what the possibilities were. Thinking in more complex ways about human nature and what you can do with that in a magazine story.

When you’re at a newspaper you’re more about reducing complexity and moving grays to black and whites. It just happens naturally with the length you’re dealing with. Jay opened the door to … the gray is the treasure, the ambiguity and paradoxes that you want to take advantage of. That’s pay dirt.

Jay, 1996.

Tom Junod: I’d read Gary Smith, worshipped Gary Smith, before I’d ever read Tom Wolfe or anybody like that. Gary was the formative guy for me. He was the guy that allowed me to think that all kinds of crazy things were possible in writing. The feeling I had when I read Gary the first time was, “Wow, you can do this? You’re allowed to do this? That’s amazing.” The kind of stuff Gary did, inhabiting different people’s voices.

When I was 29 I started writing for Atlanta Magazine, then wrote for Southpoint magazine and did a piece on Evander Holyfield that never ran because the magazine went out of business. I sent it out to Gary Smith’s editor, and one night, I’m sitting in the house with my wife, and the phone rings, I pick it up and there’s this voice, “Hello, Tom, this is Jay Lovinger and I just want to tell you that you write like a motherfucker.”

“I never knew what my weaknesses were writing for Jay. Ever.”

That’s how the call went. It wasn’t exactly a moment of arrival but it sure felt like a moment of arrival. Jay made me feel that way. Jay made me feel like I can do anything. Editors either have that or they don’t. Go with the editor that makes you feel like you can do anything cause that’s the great gift, that’s the great talent.

I just remember the look on Jay’s face when you brought in a story or when you talked about a story. He just had that twinkle. He just had that level of understanding that was peerless. It really was. The minute you came into that voice and into those eyes you just felt like you were being looked at for who you were as a writer. He didn’t see you as this complete neophyte. At the time I was in my early 30s and hadn’t done anything. Jay didn’t look at me like that, ever. He was, “We brought you in to write like a motherfucker, go ahead.”

He’d tell stories about Gary or Inside Sports and he never told those stories to make you feel like you weren’t them. He told you those stories to make you feel you were them. That’s the great difference, right? I never knew what my weaknesses were writing for Jay. Ever.

Wright Thompson: Jay exists beyond the physical constraints of time.

Jeanne Marie Laskas: I was so young and green, out of grad school, MFA program, working at my first magazine job at Pittsburgh magazine. I got my start there but was eager to try new things so I started casting a net around to see if anybody would like my writing. Randomly. Jay and Steve Petranek read what I sent.

I read The Washington Post magazine and I thought to myself I have absolutely nothing to offer this magazine. I don’t write about politics, I don’t know anything about Washington. But I wanted to do these little character studies, that was my thing. And who wants that? You gotta remember how terrified people are when they are first starting and I was.

But Jay and Steve brought me in and said, “What are these character studies?” I told them it was all the people nobody notices in Washington. The first one was about a vacuum cleaner salesman. I wanted to go door-to-door with this guy. And you could tell Jay and Steve were like, “Uh … well … try it.” To this day it’s one of my favorite stories that I ever did. I couldn’t believe Jay took a risk on it but he did.

“Overinflate the tires because you can always take air out you can’t put it in.”

He was such a risk taker on his own. He was a grown-up. I didn’t know any grown-ups that were risk takers. And who was fun. I was coming out of grad school and everything was serious, competitive and “It’s The New Yorker or bust.” So he was a beacon of hope. He wasn’t like everyone else at the Post, which gave him a license not to be like everyone else. Maybe that’s why I attached myself to him because I didn’t really fit in and the people I was writing about really didn’t fit in. To me, he was this successful weirdo.

Again, I approached it like, “What do I have to offer?” Jay was the first person to value it and that was huge. Then he gave me the green light to do a bunch of pieces for. I got a contract with the Post, quit my job, and became a full-time freelancer on the heels of that contract. Let’s see, I did an old couple who ran a junkyard; a dog trainer, which was the freakiest, weirdest story I’ve ever written in my life; a guy who ran a bra store who boasted he could fit any woman in the best bra and would change your life; oh, and the best—identical twins married to identical twins, living next door to each other in identical houses. These are really memorable stories for me. I forget a lot of other stories I’ve written but these really stick in my mind.

He put Steve Petranek in charge of me. Jay was like the Wizard of Oz, Steve was the person who would deliver me. Sometimes the top editor is the cranky one, putting the lid on things, but it was the opposite. Jay was like, “Open it up, more, more, more, it’s not too weird, don’t hold back.” I don’t know if it was Steve or Jay but one of them told me, “Overinflate the tires because you can always take air out you can’t put it in.” So they encouraged me to blow it out which was freeing. You’re trying things that other editors would make you too scared to try. I can’t think of a better training ground for a young writer. Especially when you are just starting and you are terrified.

Jay Lovinger:

The Wild Man:

Writing is a very hard way to earn a living. One of the things about being a writer I’ve always felt, is you have to be incredibly arrogant to think people want to read what you have to say about anything. And you have to be incredibly insecure to be driven to learning and getting better instead of just doing the same thing over and over again. Arrogance and insecurity is a good mix—maybe not for a husband or a father—for a writer.

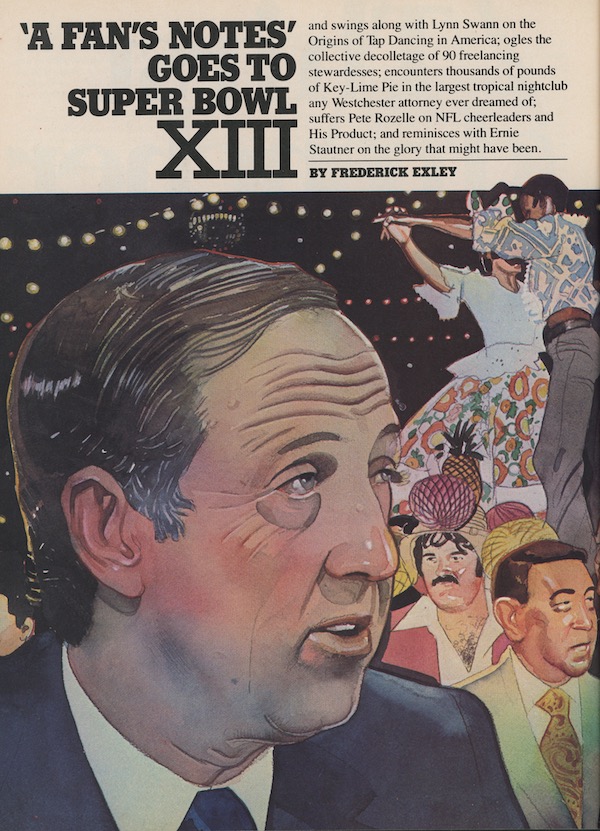

Fred Exley was maybe the most difficult writer I ever dealt with. He was such a drinker that by nine in the morning he’d be totally drunk. He was also one of those guys who wanted to argue about every change. He wrote a piece for Inside Sports about his relationship with his high school coach. Really nice piece. You couldn’t tell if it was a short story or a reported piece and we didn’t claim it as either one. The piece comes in, it’s about 6,000 words long and Walsh tells me to cut it to four and I say, “John, this is a short story by one of America’s greatest writers. You don’t cut it.” Walsh insisted that we make the cuts.

Illustration by Julian Allen.

So in order to do the piece I had to get up at seven for a couple of months and call Exley. I could hear him getting drunk on the phone and I’d argue about the story and the cuts with him. By nine he was totally out of it.

At the end of the thing he asks if I can get him 100 tickets to the Jets Giants game. Season ticket holders can’t get tickets to that game. I told him it was impossible. So he said he’d come to New York to have lunch and the last thing I want to do is have lunch with him and by noon you’d have to have an ambulance nearby to feel comfortable. So we have Fred Schruers take him to lunch and sure enough he gets bombed and wants to go over to Rolling Stone’s offices and talk to Jann Wenner. Because Rolling Stone was paying him $30,000-$40,000 a year just in case he finished the Fans’s Notes trilogy. And he hadn’t done anything in years. Jann Wenner is keeping him going for nothing. And he wants to go over to Rolling Stone and ream Jann Wenner out for some imagined reason and they go over there and he yells and curses for about an hour and then just lies down on the floor and refuses to move. I think someone finally came and took him away and when I heard this I just thought, thank God I didn’t have to go to this lunch. He’s a good writer though. He was certainly one of the best writers we had write for us.

Ethics:

I’d had this argument with Lipsyte many times. Lipsyte is a stickler. We had this argument when we were talking about Jimmy Breslin. I like Breslin very much and he cited a few things were they were at the same event and they’d both write a column the next day and their quotes weren’t alike at all.

I said, for your regular, normal writer, I’m somewhat of a stickler, although not for the quote thing because whenever people do quotes, right, if somebody said something and ten minutes later they say something else people would run that together without even thinking about it. Nobody puts “… ” where the thing is broken up. People will edit and leave stuff out. They won’t make up quotes but they edit.

Jay, 1997.

So that kind of thing doesn’t bother me at all and I think people do it all the time and if they make believe there is something wrong with that they are being hypocritical to me. But what I said to Bob is that I believe there are writers who if you were there and they were there and they could write a piece that would contain some non-factual stuff but their piece would give you a truer sense of what you saw yourself. They would tell you something about what happened that day that you yourself didn’t know even though you saw the thing yourself. So there’s something called fact, and something called truth.

Now you get into a very slippery slope because if the writer isn’t great … But to me, what you want is somebody to tell you a truth that you yourself didn’t see even though you were there. So if they make up something that is truer than factual, I’m okay with that. I know that’s not a universally held position. Especially not newspaper journalism.

“I’m not trying to make this piece into anything, I’m trying to help you do the best you’re trying to do as well as possible.”

People have called Breslin on it a lot. It’s just most people don’t care. That’s how I feel. Give me … I’d take Breslin over Kempton. And I admire Kempton. But I just love Breslin. I don’t know what that says about me but … I’m one of those people who likes that thinks the newspaper business is like the Bible. It was formed at a time when the world was completely different than it is now yet people hang on to it. Or The Constitution. I mean what would the people who wrote The Constitution have to say about the Internet? So to apply what they said in an age when there wasn’t even the phone, to the Internet. The Bible was written 5,000 years ago. What possible application could it have to what we do today?

On Getting Older (and Better):

When you’re making your own magazine it’s a 24 hour-a-day thing. Even when you’re not working you’re thinking about it all the time. I loved making things with a group of people, being part of a team of people. I didn’t like the politics. Making something new that wouldn’t otherwise have existed, to me, is the most fun. The happiest times of my career was when I was with people making something.

I think in that way I’ve become a better editor in the last few years. I used to have a striving mechanism, what I used to get ahead. And it wasn’t ever like I was bad guy or was a user of people but the way I saw writers for the most part, except for a couple of them that were my good friends, was how do I get ahead through this relationship? Where as now, when I’m not trying to become anything anymore, I’ve become much more empathetic with writers. I’m able to figure out what they are trying to do and help them do it. And I like that feeling and people respond to it. I tell writers a lot—and I really mean it—“I’m not trying to make this piece into anything, I’m trying to help you do the best you’re trying to do as well as possible.”

I never asked this until a few years ago and I don’t know why because it’s a good thing to start any editing process with. I get the draft and I say to the writer, “What do you want the reader to come out of thinking when they are finished reading this piece? What is it that you are trying to get across to the reader?” You’ll be amazed by how many times they don’t have an answer. But they’ll think about it and eventually they’ll be able to put their finger on it and then they feel like they are in control of the thing instead of me telling them, “Oh, it should be this.” And that’s a nice feeling, a much more paternal feeling. I don’t want to make myself sound great, it’s just that I can afford to do it now. So it’s kind of sweet. And it feels like the appropriate way to be at this stage in life.

A Little Bit of Luck:

I’m not sure what this means but it’s true—I’m not the nostalgic type. As soon as I’m finished with something I move onto something else. I think because my childhood was so miserable I tend to be a person who doesn’t look back, I tend to move on and get into whatever I’m doing at the moment. I spent a lot of my early life making believe I was something other than what I was. I was needy but I compensated for that by seeming to be completely un-needy. That’s why everybody used to think I was so cool. Especially younger people think that’s cool.

Sometimes, I look back at Inside Sports and it’s like a movie that happened to somebody else. I almost don’t remember that person, who I was then. And quite often don’t feel like that person. I remember what happened, I know I enjoyed it. It was like the beginning of who I am now and who I would like to think I was meant to be.

Jay and his daughter Wendy.

How much just luck and good timing can lead you to something so profoundly important in life. One of the things I’ve been thinking a lot about lately is probably the best quality a person can have is to be lucky. Because it’s so easy not to be lucky. And, of course, you don’t know all the ways you’re not lucky, because you don’t know what chances were missed—you’re reading People magazine in the doctor’s office instead of meeting the person who is going to change your life. That could happen a million times and you wouldn’t even know it.

Watching Brad Darrach write a story was exhausting. First he would take voluminous notes on yellow lined notepads, writing in an elegant, precise hand that was so compact it looked as if he were compiling an endless EKG. Next he would study the notes, committing to memory everything of meaning in them before putting them aside to think about what he wanted the story to say. Sometimes he would do this for three or four days. Finally, when all around him were losing hope, Brad would begin to write, never going on to the next sentence until the previous one was, to his mind, perfected.

This lapidary approach to writing, which has largely disappeared from the world, had three effects. The first, which never concerned Brad in the slightest, was to drive editors—including this one—temporarily insane. The second was to delight readers. A third, almost incidental effect, was to inspire several generations of magazine writers here at Time Inc. During his 50 years of writing for Time, People and Life, Brad helped create and refine the Time Inc. writing style—heavy on knockout opening lines, compressed anecdotes, wordplay, puns. In the process, he probably committed more words to slick paper than any Time Inc. writer who ever lived. In Brad’s hands, words could do almost anything—from thrill to kill to break your heart. “If there were a Cooperstown of Time Inc. writers, Brad would be in the first group of inductees,” veteran Time Inc. editor Dick Burgheim says.

For Life Brad wrote of a young Dick Cavett: “[H]e looked a little like a marshmallow lightly haired over.” Once, during his two decades as Time’s movie reviewer, he crafted this description of actor Jack Webb in Pete Kelly’s Blues: “The man lips onto a horn, or a woman, with about as much feeling as other men show for a K ration.”

But as sharp as his brain was, he more often followed his heart, which went out to almost anyone in need, from Marilyn Monroe (whose Dickensian childhood she first revealed to Brad for a Time cover story) to Liz Taylor (who chose Brad to help her write about her recent brain surgery for Life) to legions of writers, great and small—including my wife, Gay Daly, and my daughters, Woo and Wendy. When Brad finally retired from Life two years ago, Woo, then eight, and Wendy, seven, asked to give speeches at his going away party. “He helped a lot of my family enjoy writing, including me,” Woo said, as Brad beamed. Then she and Wendy sang a little song they had composed, roughly to the tune of “The Star-Spangled Banner”: “Oh, Brad, can you see/That we like you very much/And we miss you/So we hope you come back to us.”

Sadly, this was not to be. Word came that Brad, 76, had died of a heart attack on November 3 at his home in Santa Barbara. Speaking for many, Steve Petranek, the editor in chief of This Old House and a former senior editor at Life , said: “Life is a magazine about feelings, about the heart rather than the head, and in many ways Brad personified that. Generous is the right word for Brad. He never seemed to lose any part of his ego by offering brilliant help to others, and he never wanted recognition for it. He didn’t have to be credited. It was always a free gift.”

Sound familiar?

[Photo Credit: Rachel Lovinger @ Flickr]