A very big sign in red, white and blue reads, “Kennedy.” It is nailed across the front of a building three blocks from another building with another, smaller sign. This second sign is a map marked with numbers, and what I want to tell you about begins where it is, at a place an arrow designates as “You Are Here.”

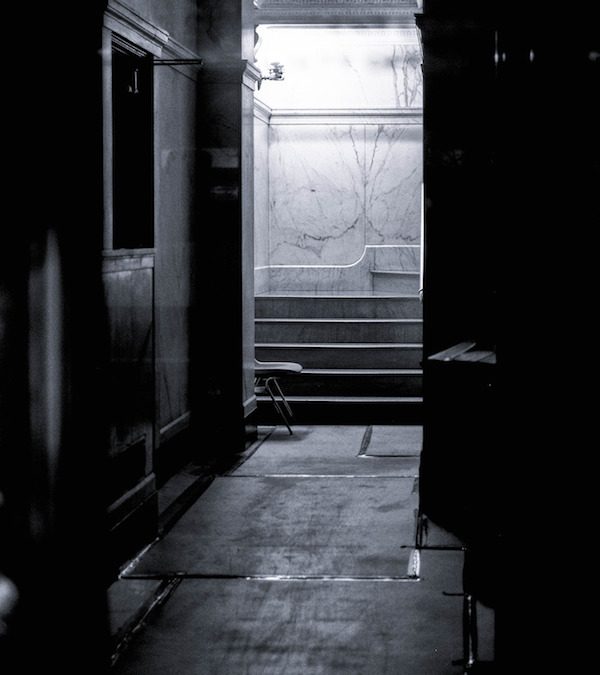

What I am looking for is not shown on the key to this map. There is, however, a spot marked number eight called “Ballroom” and, marked number nine, another room called “Colonial.” In between, unnumbered, are two small rectangles: in the middle of one is the word “stage,” in the middle of the other it says “pantry.” And those places are why I am here, standing outside the Ambassador Hotel, where Robert Kennedy was murdered in that still unnumbered area, somewhere between the spaces marked eight and nine.

I follow the map and end up where I thought I wanted to be, next to a cold and dripping ice machine where something I told myself I would never get over happened four full years ago. It is a ridiculous place for a requiem and I leave quickly because I want very badly now to make a connection with someone whose name is Juan Romero.

Perhaps you don’t remember him. He is the young man who reached the Senator just after he was shot, gave him his rosary, and was photographed as he gently held Robert Kennedy in his arms. Juan Romero is a name I just happen to remember. I do not think of him often and would not be thinking of him now if I were not in this place; but I am here, sufficiently recovered from that event to stand in the pantry of the Ambassador Hotel, haunted enough by it still to want to talk to this young man because, on that night, his face was full of the loss and horror I felt.

Juan Romero does not work at the Ambassador now. But after an hour I finally meet someone who tells me where I can find him and suggests that after 6 pm I call the number he writes out for me on a paper napkin. I do and when the telephone is answered I ask if we might meet. We agree on the day after tomorrow.

It is four years later and Juan Romero is 21 years old.

He is a very handsome young man. Tall and thin, he seems considerably older than he is perhaps because of gentleness in his face, an attitude of quiet in his bearing. His mother wanted him to get a haircut before our meeting but by the standards of 1972 his hair is extremely neat and not terribly long. He is living at home again with his mother, step-father, sisters and brothers, two of whom are lying on the floor watching Get Smart on color TV. After the assassination Juan had moved away for a while partly because he sensed the management of the Ambassador was becoming annoyed by the vast number of guests who wanted to talk to him about that night. He was becoming upset by it too, and so in the last week of 1968, he quit his busboy job. He has not been back to the Ambassador since.

On an ordinary night, Juan would have been on duty at the time of the murder. But that night, the hotel was expecting orders for champagne, not food, so Juan was let off early and decided to go and get another look at Robert Kennedy.

On the night of June 4, 1968, Juan Romero was the busboy in attendance at a dinner for four in room 514. The diners were Mr. and Mrs. Andy Williams, guests of Senator and Mrs. Robert Kennedy. Juan was excited to be that close to Kennedy for that long; his whole family liked the senator and would, several weeks later, hang a photograph of him in the living room next to an oil painting of his brother. “I’m not trying to be prejudiced,” Juan says, “but they done a lot of good for us people. You know, the ghettos. I really believe people like that would help poor people, try to straighten out people, like the kids.”

So when Kennedy won the California and South Dakota primaries that night, Juan Romero was happy and he stayed in the kitchen to see the Senator pass through on the way to his victory speech in the ballroom. As Kennedy passed him, they shook hands. On an ordinary night, Juan would have been on duty at the time of the murder. But that night, the hotel was expecting orders for champagne, not food, so Juan was let off early and decided to go and get another look at Robert Kennedy.

When the shooting began Juan thought the sound was firecrackers. Then the Senator fell and Juan thought it must be a joke, a stunt, “for publicity,” a game of some kind. Though he remembers what he thought he cannot remember what he did. Another kitchen worker, standing near him at the time, does: “Everybody runs in that moment, everybody ducks or runs away, but Romero runs to him. Remember, we didn’t know then if there was more guns, more people shooting. But Romero didn’t think about it. He went right away to give help to him.”

Juan was kneeling on the floor, holding Robert Kennedy’s head, when he felt something warm and odd, like water flowing, on his hands. “I wasn’t sure what it was, if it was the emotion I felt touching him or something. I wasn’t sure of myself so I moved my hand to look at it and there was blood on it.” It was then that Juan reached into his pocket, took out his rosary and placed it in Kennedy’s hand. Then he started shouting for a doctor. Juan does not always carry a rosary. He does not know what happened to the one he had with him that night—it was never returned to him and he did not attempt to get it back. Some people told him he should try to find it because he could sell it for a lot of money.

The rest of the night he remembers only in disconnected flashes, though he does clearly remember the photographers asking him to hold up his hands so they could photograph the blood still dripping on them, and he remembers that for the next three days he did not sleep at all. He also remembers what happened when he went to school on Wednesday morning, the day after the shooting.

The other students, children of families thought to be Robert Kennedy’s truest constituency, were not at all sad, but happily excited because of what Juan had done. For the first time in his life Juan Romero was treated as someone important, someone who matters, someone whose name and picture got in the newspapers. His classmates asked for his autograph and though Juan thought that was “real silly” he liked being the eye of this storm of attention, liked the way they gathered around him to hear him tell what had happened so they could later brag, to someone less fortunate, that they had “spoken to Juan.” He liked it until he got home and heard on the television that Kennedy was probably going to die. Then, in the small hours, came the announcement that Kennedy was dead.

Juan didn’t go back to school for two weeks. The first thing he did when he finally returned was drop out of his ROTC course which he was taking because he thought—and still thinks—that the only way he will get a good education is through the Army. “It might have been stupid,” he says now, “but I said to myself, ‘I just won’t touch a gun.’ The teachers understood.” But in those two weeks when he’d stayed home from school his family life, which had always been difficult, got worse; and so, before the school year was over, he quit school and his job, left home and Los Angeles, and went to work as a busboy in Santa Barbara.

It was there that Juan Romero learned, at the age of 17, that to run away means to take oneself along too, and so, six months later he came home, back to where a problem had begun to form in his mind of June 5, 1968, a problem that was far from solved and still growing. “After the thing was over, people started to say I was a celebrity and then I started to think, celebrity for what? Why a celebrity? Is it because a person is dying and you try to help them? Is it because a person was shot and you were there?”

This “you were there” marks the psychic place where Juan’s troubles begin, for while letters congratulating him on his behavior that night were being sent to him from all over the country and as far away as England and Spain, he knew something these people who wrote him did not know, something that frightened him all the more because it seemed no one even suspected it – simply, Juan wished that on that night, when the shots were fired, he had been “stacking tables, picking up an order, anywhere but there.” And if it was somehow unavoidable for him to have been anywhere but in that pantry, his actions seem to him useless, an after-the-fact response that helped no one, certainly nothing to be “celebrated.” To be congratulated for what he did does not make sense to him because he believes there is something else he could have done, ought to have done, and did not to. It occurred to him that he must have been standing, while waiting for Kennedy, quite near the Senator’s assassin, Sirhan Sirhan, perhaps even next to him. “If I could have had split-second reactions, you know, to either get the gun or knock it from his hand, or stand in front of Kennedy, I could have saved his life.” When I ask if what he means by “stand in front of Kennedy” is that he would have rather taken the bullet himself, he answers very quietly. “I think I would prefer that to the way the situation is now. He’s dead and I’m still living and can’t stop thinking about it. He could have done so much good for so many people and I’m just alive, sitting here.”

He could not say how meaningless he thought his action was, or that he questioned not only it’s validity but it’s motivation as well.

To further complicate the contradictions of wishing he hadn’t been there, and a sense that he could have prevented the tragedy, was a new, exceedingly uncomfortable factor – for Juan Romero, by doing a small, but decent thing, began to receive attention from people who previously might not even have tipped him. These people sought him out, offered him jobs, scholarships, even money. And as Juan saw how easily the murder of Robert Kennedy might benefit him, he wondered if somehow, on some dark level of his mind, he might have known this all along, might have known it when he ran to Kennedy, might even have tried to help Kennedy because he sensed that somehow that act could later help him. He is sure it all happened too fast for such thoughts to have occurred, but wanting to make very, very sure no one else would doubt his actions, he did not accept any of the offers.

His feelings were exacerbated by the fact that he could tell no one about them; certainly he could not explain how he felt to the people who were still congratulating him, who insisted he was a “celebrity” and even “a hero.” He could not say how meaningless he thought his action was, or that he questioned not only it’s validity but it’s motivation as well. Finally, needing to talk to someone, he did what very few people with very little money do: he went to a psychiatrist.

Mexican-Americans do not generally go to psychiatrists for reasons that are as much religious as financial. Most are devout Catholics whose problems can—hopefully—be faced and dealt with in a confessional. It was a very big step for Juan to go to this doctor and he did it because he thought it was something he had better do “before it was too late.”

Talking to the doctor helped a little, though not much. The doctor advised him to try not to think about the murder, or Kennedy, when he was alone and, when he was with people who asked him about it to try, if he could, to answer them. And when Juan told him he wished he was “in one of those fantasy machines, like in science fiction, that could take me back in time, to just before it happened,” the doctor said that in spite of that wish, in spite of everything, Juan’s life must, and will, go on.

Which, of course, it has.

This year Juan went back to finish high school. He was surprised to learn he is too old for regular classes; he would have to go at night now. Each morning he gets up at 5, goes to work in a Laundromat at 6; most evenings before school he plays basketball. He hopes to graduate before his brother who is five years younger. If he does, he will be the first member of his family to get a high school diploma. Then maybe college, maybe the army. He would like to be a mechanic but that is unlikely because “it takes too long.” He knows that someday he will want a wife and children so he is trying hard to improve himself; he says he “can use a lot of improving.”

Though he has tried to follow the doctor’s advice and not think of Kennedy, he still dreams of him, dreams in which, for example, they are flying together in an airplane, the only passengers. Something goes wrong, he does not know what, and then they are floating together, supported by parachutes as they descend through the blue, blue sky, moving slowly down, down to the sea which, at the very last moment, turns out to be made not of water, but of popcorn.

When he has these dreams they come back to him slowly, in pieces, so that while he is working at the Laundromat he will remember another, and then another, and then another instance of his being alone with Robert Kennedy, both of them laughing, both unhurt.

Those days, he says, the days he is remembering his dreams, are happy for him.

When I left Romero’s house, I drove back to the Ambassador, as if the physical going from the one place to the other could close the gap between where we have been, where we are, and where we may be headed.

Juan had told me he will not vote in this year’s Presidential election unless one of the candidates is Edward Kennedy. Juan is hoping he will run “so his brothers will not have died in vain.”

That hope of Juan’s was as close as I may ever come to finding that link between then and now; it is what I was thinking about when I drove past the Ambassador and first saw that sign, the red, white and blue one, with the name “Kennedy.” I looked at it and wondered how it could be that in all these years no one had bothered to take it down. Then the light changed and, moving the car forward, I saw that the sign was wrapped around a building that curves, so all the words on it could not be seen, at once, from a distance.

What the sign said was “Ted Kennedy…1972.”

Postscript:

This is the first piece I ever wrote. It was not an assignment. It happened because I was invited to lunch by a woman who chose to meet at a place I’d avoided assiduously. That place was the Ambassador Hotel, where Robert Kennedy was murdered. I had not simply supported Robert Kennedy. I had believed in him. The first time I voted, I voted for him; it was an angry vote for he was dead by then. I can’t remember if I wrote his name in, or if it was still on the New York State primary ballot.

Four years later, I wrote this piece and sent it to a few publications. Rolling Stone sent me their stock postcard-sized rejection which was printed on heavy paper and looked like a wedding invitation. A few weeks later I got a letter from Ross Wetzsteon, the editor of the Village Voice. The first words were “I’m sorry” and I threw it on the floor and tried not to think about it. When I finally picked it up hours later, with the intention of tossing it out, I happened to notice some words at the end “because I very much want to publish this piece.” What Ross had written was that he was sorry to ask me to make any changes to the piece but he had a few suggestions and hoped I would agree with them.

What was amazing about this is that my piece arrived at the Voice “over the transom”— as we used to say—which meant it was one of countless pieces that were unassigned, written“on spec”—pieces which invariably landed in what was inelegantly known as “the slush pile.” Ross Wetzsteon was an amazing editor-in-chief in many respects, not least of which being that he personally read that slush pile.

One thing I didn’t mention in the piece was that when I first called Juan Romero and asked to see him he said no, he wouldn’t meet with me, adding that he had never spoken to a reporter, and never would. I wasn’t a reporter then of course; I’d never reported anything or written an article in my life, though I’d always wanted to but had never quite summoned the courage. All I could claim for myself was that I needed to make a connection with this young man who had cradled Robert Kennedy in his arms as he lay dying. “You don’t understand,” I said, “I have to meet you.” It was then that he agreed to see me. This was an act of pure kindness, but then, my need to see him was predicated on that other occasion when he had been kind.—Elizabeth Kaye

[Photo Credit: Bags]

First reprinted at the Daily Beast