It is the day before the Academy Awards. There is a small crowd of people standing in a light rain outside the stage door entrance to the Music Center, in downtown Los Angeles. The rain has been falling all day, and now, at dusk, the city seems to be vanishing in a B-movie mist.

Across the street from the theater, an old man is sitting on a bench in front of the county courthouse. His hat is tipped forward on his head in the suggestion of an earlier day’s flamboyance. Pigeons are splashing in the puddles of rain water that lie at the old man’s feet. The old man in the hat regards the pigeons in silence as they strut arrogantly up to the tips of his black-and-white sneakers, then turn and walk away.

Suddenly, with a clatter, the door to the theater opens and two men walk out.

“Is it anybody?” someone at the rear calls out. “Can anybody up there see?”

The two men emerge from the building as if they are on a mission of great importance. They ease into the crowd; they are both wearing plastic raincoats with colored identification tags clipped to the front.

“Forget it,” someone else says. “They’re nobody.”

“Wouldn’t you know?” a woman says aloud. She pulls a handkerchief from the sleeve of her coat and blows her nose with disgust.

The two men who are nobody come out to the sidewalk and look up at the darkened skies.

“Think it’s going to rain?” one man says to the other.

“What are you, an asshole?” the other man says. The man is carrying a bottle of orange soda in his hand; he tilts the bottle to his mouth and takes a long drink.

“It’s raining right now.” he explains. He looks up at the sky and smiles.

“Son of a bitch,” he says. “Lot of nervous hairdressers in this town today, know what I mean?”

The first man sneezes violently; he wipes his nose with the back of his hand.

“You know what I think?” he says. He clears his throat and spits into the street. “I think it’s God’s little way of pissing on Hollywood.”

“Hah,” the other man says. This idea seems to please him.

“Excuse me,” a woman’s voice says.

The voice belongs to a short, heavy-set woman with red hair and galoshes. A small, ruby-colored heart hanging from a chain lies pressed against the upper slope of her enormous bosom like a stranded mountain climber.

“Are you with the television?” she says.

“Yes, ma’am,” the first man says. He points to the identification tag on his raincoat. “That’s what it says.”

The woman takes a step toward the man and stares at him with determination; thick swirls of lavender shadow surround her eyes like the rings of Saturn.

“I couldn’t help but noticing,” she says, “that you just came from inside there.”

She gestures toward the doorway of the theater.

“The lady’s got an eye, Ace,” the man with the orange soda says. He gives the woman in the galoshes a toothy smile.

The woman looks at the man with the orange soda as one might look at a cockroach.

“Does that mean,” she says, turning to the man who is called Ace, “that they’re still doing whatever they’re doing in there?”

“Rehearsing,” Ace says. “Yes, ma’am, be rehearsing all night. Wouldn’t you say all night, Irving?”

“All night,” Irving says.

“Well, then, maybe you boys could tell me something,” the red-haired woman says. “Maybe you could tell me who’s in there.”

“Who are you looking for,” Irving says, “specifically?”

“Oh, you know,” the woman says. “Movie people.”

“Ah,” Irving says. “Well, we have a lot of movie people in there, don’t we, Ace?”

“Surely do,” Ace says. “Who’s your favorite, sweetheart?”

The woman in the galoshes blushes.

“Telly Savalas,” she says.

“Telly Savalas isn’t a movie person, lady,” Irving says. “He’s a television person. How about Gene Kelly? He’s inside.”

The woman seems disappointed.

“No,” she says. “I was thinking about someone, you know, more recent.”

“Hmmm,” Irving says.

“Well, look here,” Ace says suddenly. He points down the sidewalk to the garage.

“This is your lucky day, lady. I have a movie person in sight.”

“Where?” the red-haired lady cries. She grabs Ace’s arm, pulling him off balance.

“Who is it? Tell me who it is!”

“Someone’s coming!” a woman calls out shrilly. She quickly produces an Instamatic camera from her purse.

The crowd comes to life with all the urgency of a fire company responding to a four-alarm blaze. People jostle one another as they push forward and fill the stage-door area, creating a human barricade to the building’s entrance. A lady’s handbag is knocked from her grasp and the contents go crashing onto the rain-soaked sidewalk; a small, flowered lipstick container rolls into the gutter and floats like a corpse in the tiny stream.

A cool-eyed cop with a walkie-talkie dangling from his belt comes out of the building like a battleship under power and begins pushing people away in different directions.

“It’s a woman,” someone says. “I see a woman and a man.”

“There’s another woman there. Two women.”

“And a man. Who’s the man?”

“Who’s the woman?”

“That second woman’s nobody. She’s carrying things.”

“Oh, I see her!” the red-haired lady with the galoshes squeals. “It’s Katharine Ross!”

“Way off, lady,” Irving says. “Way off.”

The three new arrivals approach the theater slowly but with no visible signs of apprehension.

The man walks on the inside, closest to the building. He glances about him with the casual interest of someone taking a stroll through the zoo. The woman who is carrying things walks on the outside, closest to the street. She clutches her belongings close to her, as if they might be wrestled from her arms by a band of urchins. In the middle is a tall woman, walking perfectly erect, dressed in a plain beige raincoat. She wears an unpatterned scarf on her head. She stares straight ahead at the mob in her path through a pair of thin, gold-framed glasses. Her face shows no expression whatsoever.

“It’s Raquel!” someone cries. “Oh, my God! Raquel!”

“I’ve lost my pen,” someone else says. “Does anybody have a pen?”

“Goddamn camera,” a man says, doubled over in his attempt to attach a lens.

“Goddamn son-of-a-bitch fucking camera!”

Raquel and her two companions arrive flush with the crowd and begin to make their way to the entrance of the building. Flashbulbs pop in the mist, like miniature novae. The cool-eyed cop is holding people back with two outstretched arms; the walkie-talkie on his belt crackles with the sound of a disembodied voice.

“My daughter loves you!” a woman is shouting. “Sign this for my daughter!”

A small man with dark complexion darts suddenly out of the throng and thrusts himself into Raquel’s path. He is wearing an ill-fitting shimmering brown suit that hangs on his slight frame like a shroud. He holds a large, hardbound book in his hand with his finger marking a place in the middle. His eyes are ablaze.

“What say, mate?” the man who is with Raquel says in a crisp English accent. He smiles affably at the man in the shimmering suit. “Could we make a little room for the ladies here?”

The dark-complexioned man says nothing. He opens the book and holds it in front of him in his upturned palms like a deacon serving High Mass.

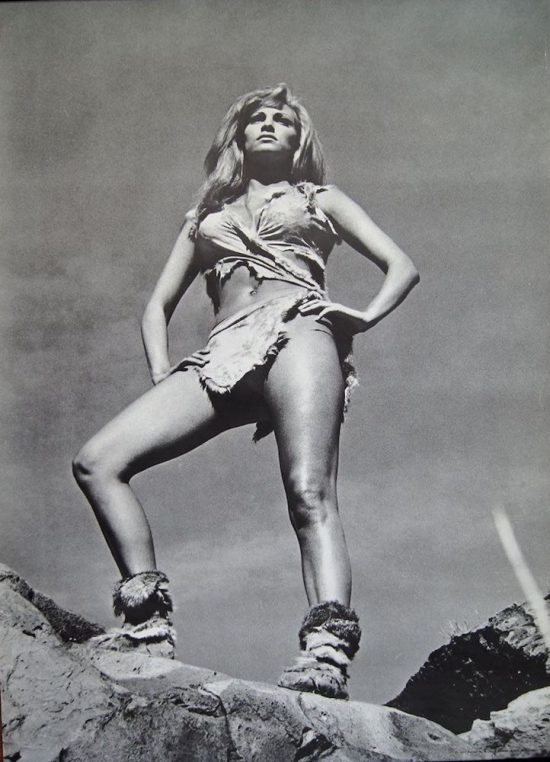

The book is open to a page that bears the heading: Welch, Raquel. There is a short biographical paragraph framed by several photographs. The most prominent of these shows Raquel dressed in a brief leatherette jumper. Her breasts spill voluptuously over the confines of her halter top; her hair hangs about her head in frenzied disarray; her mouth pouts; her eyes beckon.

Raquel looks down at the photograph over the top of her glasses. She stares at it for several moments, seemingly without comprehension. The face in the picture leers back at her lewdly.

The cop with the walkie-talkie advances on the small man in the ill-fitting suit and takes him by the arm.

“OK, Butch,” he tells him. “Let’s get it in gear.”

The cop pins the small man’s arm behind his back, twirls him around and launches him into the crowd. The book is torn from the man’s hands and falls to the ground; the pages are caught in the breeze and the picture of Raquel, resplendent in her leather sexuality, disappears.

The cop clears the way and Raquel and her two friends walk quickly into the theater.

At the edge of the sidewalk, the red-haired lady with the galoshes is standing motionless, watching Raquel fade from view. She holds her hands clasped in front of her fervently. Her eyes have become enormous; she seems transfixed.

“Got a live one, right, lady?” Ace says to her.

“It was Raquel,” the lady says in a faraway voice. “It was Raquel.”

“We knew you were coming, doll,” Ace says cheerfully. “We set it up special.”

The lady turns and looks at the two television men.

“She’s so … so….” The lady gestures helplessly. Words fail her.

“Yeah, I know what you mean,” Irving says. “I always say actresses are a dime a dozen, but a great pair of boobs is a joy forever.”

He puts his arm around the red-haired lady’s shoulders and smiles at her with warm camaraderie.

“That’s what I always say,” he tells her. “What do you always say, lady?”

The hallway is filled with people. A half-dozen girls in elaborate costumes come breezing down the stairway, their high heels clicking on the concrete steps. A young man with thinning hair and a scarf around his neck meets them at the bottom.

“You girls in the Lauren Bacall number?” he asks.

Nobody answers him.

The man refers to a clipboard in his hand.

“We’ll need you back upstairs in twenty minutes,” he says. “Make that fifteen. Oh, and sweetheart,” he adds, tapping one of the girls lightly on the arm, “your feathers are on crooked.”

The man hurries up the steps, looking at his watch.

The girl with the crooked feathers looks after the man with a homicidal stare. She minces his walk for her companions.

“Shove it up your ass, Tinker Bell,” she hisses.

Raquel and the two people with her come through a doorway and into the corridor. The people crowding the hall pay no attention to her. There are long lines at the telephones and the soft drink machines. A loud speaker is broadcasting the rehearsal that is going on upstairs.

Two security guards standing with their backs to a wall watch her walk past. One of the guards looks at the other and winks; he holds his hands cupped in front of his chest, as if he is grappling with two oversized grapefruits.

“Shit,” the other man tells him.

Upstairs, the center aisle has been rendered impassable with cables and equipment. There are people scattered about in the seats, talking, sleeping, smoking cigarettes in casual defiance of the signs; there are people roaming the side aisles, in groups and alone; there is quite a bit of shouting going on around the stage area. For all the activity, there is no sense of cohesive action.

At one side of the enormous stage, a bearded man with a headset is trying to pull the rehearsal together.

“Could we have Jack Valenti up here, please?” he says. He shades his eyes with his hand and searches the perimeter of the lights.

“We have to move quickly here, people,” he says in a small shout.

Raquel stands just inside the doorway and looks about her uncertainly. There is a tall man in a green sports jacket standing nearby, yelling into a telephone.

“The fucking musicians can go home when we’re through,” he says into the receiver, “that’s when they can go home!”

There is a brief pause as the man listens to the other end; his face colors slightly and the veins on his temples become prominent.

“Don’t tell me about the union,” he says menacingly. “The union can suck my dick.”

The man slams the telephone down as if his intention is to destroy it. He looks up and sees Raquel standing quietly in the aisle.

“Well, now!” he says, breaking into a large smile. “Glad you’re here! Great you’re here! Just take a seat—anywhere—be comfortable. Get with you in a minute.”

Raquel walks to one of the rows of seats down front and moves into the middle. She leans forward and looks back in the direction of the man with the green sports jacket.

The man has Sammy Davis Jr. standing beside him; Davis is talking with a great deal of animation and the man has arranged his face into a configuration of attentiveness. Davis points to his watch as he speaks, then swings his hand around toward the stage. The man also looks at the stage, as if there has been an apparition, then spreads his hands apart and shakes his head sadly from side to side. Davis stares at the man for a moment, then throws his arms up in the air and walks away. The man in the green sports jacket watches him go with a mixture of concern and relief.

As Davis moves off to find a seat, he spots Raquel and gives her the wave of a man in a lifeboat signaling to a plane.

“Look who’s here!” he calls out over several rows.

Raquel laughs and returns the wave. Davis makes his way over to her with a great display of enthusiasm.

“Just look who’s here,” he says again; he bends over to kiss Raquel on the cheek.

“Come down here to do nothin’ with the rest of the folks? We thought you were lost or something.”

“It was the traffic,” Raquel says. She removes her scarf and shakes her hair loose.

“The freeway was unbelievable.”

“It’s the rain,” Davis says. “Weird time for it to start raining.”

“I don’t know,” Raquel says to him, “if you’ve met my secretary, Mary Bredan….”

She gestures to the woman next to her.

“Hello, Mary,” Davis says.

“And a dear friend of mine from London, Terry O’Neill,” Raquel continues.

Davis spins around to take the Englishman’s hand. “Hello, Terry,” he says. He looks at Raquel. “They rhyme.”

“Hah … yes, well …” Terry says. He looks away.

“Terry is the number-one ace photographer in the world,” Raquel tells Davis.

“Bit of an overstatement, actually,” Terry says.

“Not at all,” Raquel says, waving this away. She eases out of her raincoat and glances up at the stage.

“I know I’m dreadfully late,” she says. “I was supposed to be here forty-five minutes ago, but that damn freeway—unbelievable.”

“Haven’t missed nothin’,” Davis says. “Nothin’ to miss. I’ve been waiting for them to run through my medley—I’m ready but alone, if you see what I’m saying.”

“Why it’s always necessary to do things this way,” Raquel says, “I have no idea.”

“Well,” Davis says, “that’s showbiz, baby.” He lifts himself up onto the toes of his madras-patterned platform shoes and tries to catch the eye of the bearded man with the headset.

“Ready for me’?” he calls out loudly. He points with his index finger to the top of his head, so that there is no confusion; a large supply of jewelry rattles around like kitchenware on his wrist.

The bearded man onstage is supporting his forehead with the palm of his hand, like an illusionist summoning up a card trick. A gigantic replica of the Oscar statue looms over him like an enormous phallus.

“Cat’s head is flying half fare,” Davis says, jerking his thumb in the bearded man’s direction. He takes a seat next to Raquel.

“Is it always this, ah, disorganized?” Terry asks.

Onstage, the girls in the feathered costumes have arrived for their dance number. A man with a stop watch hanging from his neck stands in front of them with his hands on his hips. He stamps his foot loudly on the floor boards.

“There are five girls here,” he calls out impatiently. “One, two, three, four, five. There are supposed to be six girls here. One, two, three, four, five, six!”

“It is always,” Raquel says, “this disorganized.”

“Once,” Davis says, “a couple of years ago, they had it all pulled together real tight. People showed up and didn’t recognize where they were, so they had to cut it out.”

“I think it’s grand fun,” the secretary says. “Really, I do.”

“That’s because you’re not a performer, Mary,” Raquel says.

“Say amen to that,” Davis says.

“I just hope they give me something funny to say,” Raquel says. “They never give me any funny lines. They just have me read all those dreadful names.”

“Yeah,” Davis says. “They got some funky folks on those lists.”

“I can’t decide,” Raquel says, “whether I should wear my glasses or not. I’ll see better, of course….”

She takes off her glasses and holds them in front of her at arm’s length.

“But then, on the other hand, I’ll look like a person wearing glasses.”

“Well, don’t misunderstand me,” Davis says, “and it ain’t none of my business, but I don’t think anybody’s gonna be exactly noticing the glasses. If you know what I mean.”

“I think you look lovely in glasses,” Mary says to Raquel. “I honestly think that.”

“Make you look a bit intellectual, they do,” Terry tells her.

“God forbid,” Raquel says.

“An intellectual sex symbol,” Terry says. “Could become the rage.”

“Don’t start that sex-symbol stuff with me, Terry,” Raquel says. “You know I loathe that.”

“Bit of a joke,” Terry says.

“Can’t disappoint the public, baby,” Davis says. “People might never recover. Did they get you outside the door?”

Raquel nods wearily.

“Some crazy acts out there,” Davis says. “In the rain and everything. Dedication, Jack.”

“I don’t mind it,” Raquel says, “I really don’t mind it most of the time. But sometimes people can be so … strange.”

“There was one bloke outside,” Terry says, “positively off his tune.”

“We were coming in,” Raquel says, “and this little man just came out of no where and he just stared at me.”

Davis laughs as if Raquel has told him a joke.

“I mean, really …” Raquel says.

“Well,” Davis says, “that’s what comes with the job. That’s what they mean when they say it comes with the job. That’s what they’re talking about.”

“Yes,” Raquel says. “I know.”

“When you walk out of your house, man, in the morning,” Davis says; he leans back and puts his shoe on the seat in front of him, “you gotta put on your face. ‘Cause people are gonna be lookin’, right? You know it. But that ain’t the killer. It’s when they stop lookin’….”

“Ladies and gentlemen, your attention, please,” the loud-speaker announces. “We need Susan George onstage now. Could we have Miss George up here, please?”

“Aw, no!” Davis says with disgust. “Ain’t this nothin’?” He checks his watch, a small face on a diamond-studded band. “Past my dinnertime and everything.”

He gets to his feet and smoothes the seat of his trousers with the palms of his hands.

“Gotta go see what’s what,” he says. “Clean up a few acts. Nice meeting you, folks.” He winks at Raquel. “Be cool.”

“Such a nice man,” Mary says as Davis walks away.

“Champion bloke,” Terry says. “Tired, Rocky?”

Raquel has her hand over her mouth, smothering a yawn.

“I just want to do this and get out of here,” Raquel says. She yawns again. “I mean, I know what it’s going to be. I know there aren’t going to be any funny lines … I know that.”

“These are the nominations for Best Foreign Film,” Susan George is saying onstage. She squints into the distance. “No, sorry,” she says. “Can’t read them from here.”

“I’m going to wear my glasses,” Raquel says. “The hell with it. It’s going to be bad enough as it is without stumbling over the frigging cards.”

“Not to worry. Nobody listens to the petty names. Feel free to improvise, if you like.”

A thin, erudite-looking man in his 60s has appeared at Raquel’s side. He offers his hand to her formally.

“I’m Leonard Spigelgass,” he announces, with a slight bow of his head. “I am the author of … all this.”

He takes in the entire production with a casual gesture.

“I’m Raquel,” Raquel says.

“Yes,” the man says, “of course you are. And it is my singular pleasure to inform you that your services will be required shortly. Isn’t that nice?”

The man settles into a seat and smiles at Raquel pleasantly.

“Quite a little flurry here, isn’t it?” he says. He takes a roll of peppermint Life Savers out of his pocket and pops one into his mouth. “Extraordinary, really. Life Saver?” he says, extending the pack to Raquel.

“No, no thank you,” Raquel says. She looks at the back of her hands for a moment. “Did I understand from what you said that you, ah, wrote this show?” she asks.

“That is correct,” the man says. “If you want to call it writing. Some would. Thousands wouldn’t. More a matter of sheer will than writing. More a matter of money than anything else, if the truth be known.”

“Do I have any good lines?” Raquel says. “A joke or something, you know, some little funny something.”

“Nothing,” the man says, without hesitation. “Not a one. But then, it’s not the sort of thing that really matters, is it? It just goes out over the airwaves and disappears. Just goes away. Like a passing storm.” He breaks his Life Saver with his teeth. “Just like that.”

“I’m not sure I understand,” Raquel says.

“This,” the man says, pointing around him. “It doesn’t matter.” He looks at Raquel closely. “You know what I mean by matter, don’t you? A play, for example. That matters. A book matters. These are things with thought. For thinking people.” He taps his temple with his index finger. “But this! This is a collection of adjectives, is all it is. Stupendous, marvelous, delightful, incredible….” He ticks these words off on his fingers. “You see? What difference does it make?”

“Well,” Raquel says slowly. “If you’re talking about the Academy Awards—I assume that is what you’re talking about.”

“Precisely,” the man says.

“Well, I think this all serves a very important function to the motion picture business,” she says. “I think it generates interest in movies with the public. I think it does that.”

“And that matters?” the man says. He raises his eyebrows in amazement.

“Well, yes,” Raquel says. She stops a moment. “It matters to me.”

“Ah,” he says, absorbing this. “Why is that?”

“Why? Why, because I’m an actress, is why,” Raquel says. “I act in the movies. I want people to go to the movies.”

“Fascinating,” the man says. He seems surprised. “You care about the movies, do you? You believe in the motion picture arts?”

“Of course I do,” Raquel says. “Doesn’t everybody here? I mean … isn’t that what this is all about?”

“Publicity,” the man says in a confidential tone. He gives Raquel a knowing look.

“That’s what all this is about.” He rests his hand on her arm. “What I’m asking is, do you feel that people going to the movies is worth while? Are we accomplishing anything by what we do?”

Raquel leans away and studies the man for several moments. Her eyes narrow somewhat and her mouth tightens slightly.

“Look,” she says, “I just make my living doing what I know how to do. And I want to keep on making my living and that’s why I’m here and I’d say that’s probably why everybody’s here. I’m just a working actress, that’s all. I don’t think about it philosophically.” She sighs and rubs her hand across her forehead. “I just … don’t think about it that way.”

“Yes,” the man says. “Well, I’ve often suspected that art without philosophy was what the movies were all about. Perhaps so, hmmm? Ah!” He raises his hand to his ear like a silent-film cowboy aware of the approaching Indians.

“They’re calling your name,” he says to Raquel.

“Wonderful,” Raquel says. She stands and stretches her arms out from her sides. She rubs her fingers through her hair, brushing it backward. She dabs with her hand at the sides of her nose.

“Would you like a mirror?” her secretary asks her.

“This is a rehearsal, Mary,” Raquel says, “not dinner for twelve.”

She straightens her sweater and moves out of the row. In the aisle, two men are arguing about the chances of the Rams’ acquiring Joe Namath. Overhead, a bank of lights goes unexpectedly dark and one corner of the theater turns black.

“All right,” someone yells, “who’s fucking around with the goddamn board?”

Raquel hurries down the aisle and starts up the steps to the stage. As she reaches the last step, her foot catches on one of the thin cables that crisscross the stage like ivy roots. Her glasses slip from her head and drop to the floor. As she stoops to recover them, she sees that one of the lenses has popped free. She holds the broken spectacles in her hand as if she were cradling a wounded sparrow.

A stagehand dressed in a sweater as orange as the sunset on the ocean gives her a sympathetic look.

“Can I get you anything?” he asks.

Raquel looks up at the stage and out at the theater. She turns back to the man and shakes her head.

“You wouldn’t know where to begin,” she tells him.

A rail-thin young man with closely cropped hair is standing by the door of the restaurant. He is wearing a strawberry-colored Western shirt with a sequined cowboy stitched on the back. He taps a yellow pencil against his teeth and stares without interest through the open doorway and beyond to the traffic on Santa Monica Boulevard.

A waitress on her way by makes a toy gun out of her hand and presses it into the young man’s back.

“OK, Tex,” she purrs, “let’s see your piece.”

The young man doesn’t take his eyes away from the street. He twirls his pencil reflectively.

“Don’t fuck with me, Margot,” he tells the girl.

“Not me, lover,” Margot says. She pokes the young man with her gun again.

“Did you see who we’ve got in the back tonight?” she asks him.

The young man turns to look at the girl; he is a masterpiece of ennui.

“I’ve been at the door all evening, Margot,” he says. “I know who’s here.”

“I see,” Margot says. “Well, I guess sex symbols just don’t do anything for you, right, cowboy?” She pats him on the cheek and begins to walk away. “You being a faggot and everything,” she says over her shoulder.

Margot glides away, giggling merrily.

Raquel, sitting at a table at the back of the room, rubs the stem of her wine glass with her fingers.

“I live here,” she says, “and I can tell you that there are people in this town who you don’t see anywhere else.”

“It’s the movies,” Terry says. “What it is.”

“Yes, it’s the movies,” Raquel says. “But there’s something more, something about this place. I think maybe it’s the weather.”

“Keeps people warm, it does,” Terry says. “Keeps them out in the open.”

“Well, you do stay warm. Which, believe me, is a big plus if you happen to be … without resources.” She glances around the restaurant. “This town is paradise for people without resources.”

“I see,” Terry says. “Broke, you mean?”

“Yes,” Raquel says. “You can live on the air here. Of course, when I was here and broke, I thought all the good things were waiting somewhere else. New York, that’s where I thought everything was. And that’s where I went, which I should have had my head examined for. I had two kids and not a penny, you realize, but I was off to New York to be a star.” She smiles at herself. “Good old Rocky,” she says.

“And you got how far?” Terry says.

“Texas,” Raquel says. “Terry, I know you’ve already heard this story. I haven’t gone senile. I was just making a point.”

“Sorry,” he says. “Just a bit of Greek chorus, is all.”

“You are really quite impossible, Terry,” Raquel says.

She picks up a menu lying on the table and begins to study it.

“Do you think you would have been better off?” Terry says to her after a moment.

“Better off?” Raquel says. “What are you talking about?”

“Had you gone on to New York. Done theatrical things. Somewhat of a rhetorical question, actually, considering—”

“God, no,” Raquel says. She flips the menu over and looks at the desserts. “If I’d gone to New York, I would have died. I would have literally died. I realized that when I got to Texas. I could feel the weather changing one night and I knew the farther East I went, the colder it was going to get, until finally I’d get to New York, where I’d freeze to death.”

She folds her menu and puts it down.

“It was winter, you see,” she says.

“Yes,” Terry says.

“Well,” she says, “I decided that I was prepared to starve, but I was sure as hell not going to freeze.”

Raquel picks up her glass and takes a ladylike sip of wine.

“If what you want to do is survive,” she says, “then you should do it where the sun is shining and the weather is warm.”

“I’ll drink to that,” Terry says. He raises his glass in what could be considered a toast to the restaurant at large. “Here’s to all the survivors gathered here. Just one big lifeboat, it is.”

“To all the refugees,” Raquel says, “from all the sinking ships.”

“May none of them be us,” Terry says solemnly.

As they celebrate this concept, a waiter in a striped T-shirt and a blue-denim apron approaches the table. He reaches for a pad and pencil and smiles congenially at everyone present.

“Hello, my name is Dave,” he says. “I’m your waiter for this evening.”

“Bloody marvelous,” Terry says. “Everybody ready here? Ladies first, I imagine. Rocky?”

“Uh,” Raquel says, “yes, well, let me see, I’m not quite….”

She picks up her menu and looks at it intently. Dave holds his pencil poised above his pad.

“What … ah … ohhhhjesus….” Raquel runs her finger over the menu, as if it were written in braille. “What is the Anything Goes Salad?” she says finally. “What would that be?”

“Well,” Dave says, “it’s a salad. It’s made with three types of lettuce: Bibb, iceberg and romaine; and it has bean sprouts, garbanzo beans, kidney beans, carrots, hearts of palm, mushrooms, avocado, tomato, water chestnuts, raisins, pine nuts, dandelion greens, asparagus, anchovies, green pepper, cheese—”

“Ah,” Raquel says.

“And a dollop of yogurt,” Dave says. “You choose your flavor.”

“Yes,” Raquel says. “I’m sure you do. But I think I’ll just have fish.” She consults her menu again. “I’ll have the rainbow trout, please.”

“On the dinner?” Dave says.

“No, just fish.” Raquel says. “Just fish, on a plate.”

“You get soup with that,” Dave says. “You can have cream of mushroom, clam chowder, split pea—”

“Just fish,” Raquel says. “That’s all.”

“Just fish,” Dave says. He writes the order down. “OK, then, anybody else on a diet here?”

“I’ll have the same thing,” Mary says. “I’ll have the fish as well.”

“Two fish,” Dave says. “I have two fish. Will it be three fish?”

“I’d like a cheeseburger, if you can manage one,” Terry says.

“Nothing to it,” Dave says. “One hamburger platter—”

“But with cheese,” Terry says.

“But with cheese,” Dave says. “OK, I guess that takes care of that. Food will be here shortly. Enjoy yourselves.”

He casually picks up the three menus, tucks them under his arm and departs.

“My goodness,” Mary says, after the waiter is gone. “Isn’t he the odd one?”

“Probably an actor,” Raquel says. “Sometimes it seems that everyone is in show business. It gets quite tiresome, really, if you want to know the truth.”

“Bloke’s probably the hit of the kitchen,” Terry says.

“Without a doubt,” Raquel says. “Very tiresome.”

She takes a cigarette from a pack lying on the table and Terry produces a lighter for her with gentlemanly dispatch.

“Or am I not supposed to do that?” he asks, snapping the lighter shut.

“Either way,” Raquel says. “As it happens, I don’t have a match.”

She leans back in her chair and smokes her cigarette. She closes her eyes.

“So he’s got them fucked,” a man at another table is saying in a rising voice, “and he makes the deal, they give him the deal, they let him direct the picture. The thing is, he doesn’t know dildo about directing. He’s down in Florida forever, they’re losing money on a minute-to-minute basis, they finally wrap it up, bring it back, they look at the film and they absolutely shit their pants. Absolutely shit their pants.”

“You’re right, Terry,” Raquel says, opening her eyes. “The movies have made this town as comical as it is. There’s no other excuse for some of these people.”

“Movie people are super,” Terry says. He unwraps a packet of saltines and pops one of the crackers into his mouth. “They exist, somehow, almost exclusively on the symbolic level, don’t they? Greed, passion, treachery, fear.” He crumples the cellophane and drops it into an ashtray. “Dostoievsky should have seen Hollywood.”

“It would have depressed him,” Raquel says.

“Hah,” Terry says. “Yes, well. People suit their environment, Rocky. If you go to Paris, you see Parisians. Can’t help it, really. Same thing here. Yon come to Beverly Hills and people are talking deals. Movie deals. It’s an entertainment, in its way. Gives the town some jazz.”

“You can carry anything too far,” Raquel says. “The Hollywood mindset adores excess.”

“They adore themselves,” Terry says matter-of-factly. “This is a narcissistic town, luv. Beauty and pizzazz. Whose tits stand firmer? and so forth. New York, on the other hand, is a chauvinistic town. Quite the other thing.”

“I see,” Raquel says.

“Like night and day,” he says.

“Well,” she says, “I think when you’re monopolized by one attitude, whatever it is, it’s a drag. You don’t see right after a while. You’re at the mercy of events.”

She exhales a final trail of smoke and puts out her cigarette.

“That’s living in this town,” she says, “being at the mercy of events. You have three big fears: fire, earthquake and being out of step with everybody else. The last is the worst, because when you get to that, you just disappear. You’re gone.”

“Retire to the Continent,” Terry says.

“Or Seattle or someplace,” Raquel says. “But at least the people here keep smiling, no matter what. This would be a miserable place to live if it weren’t a rule of Hollywood etiquette that one must maintain a lighthearted humor even in distress. New York is much worse, as far as that goes. New York is outrageous. Not only are people consumed by their own world … their own crazy world … but they’re so terribly serious about it as well. Christ.

“I was in Washington last week,” she says. “At a White House dinner. Talk about serious.” She rolls her eyes. “I came away depressed beyond belief, it was so unbearably dull.”

“Dull at the White House, is it?” Terry says.

“The White House, Washington—the whole thing,” Raquel says. “The people.

They were beyond description. Terry. So boring. I felt as if I couldn’t catch my breath properly.”

“They were all alike.” Mary says with consideration. “All the same thing, it seemed like.”

“Everybody was very solicitous,” Raquel says, “and very gracious, but they were all so”—she searches for a word—”boring,” she says finally. “No spark at all. The Fords were nice, they seemed to have a little sense of humor about the whole thing, but the rest—zero.” She makes a large circle with the thumb and index finger of both hands. “And these are our leaders,” she says.

“How disquieting,” Terry says.

“Yes,” Raquel says. “You know, I was at a party the other night at the Bistro that was being held in somebody or another’s honor … I can’t seem to remember who.” She stops and taps her forehead in an attempt at recollection.

“Well, “ she says after a moment, “I guess it couldn’t have been anybody very important. Anyway, Henry Kissinger was—”

“Oh, he’s important,” Mary says, trilling somewhat.

“Yes, but it wasn’t his party, Mary,” Raquel says. “He was only there.” She pauses long enough for this distinction to be made. “Anyway” she goes on, “I was telling him about Washington and being there and how intense everybody seemed … you know … and he just smiled, this little secret sort of smile, and he said very softly. ‘Zeze people play for keeps!’ ”

“Ha!” Terry says. He laughs appreciatively. “He said that, did he?”

“He’s marvelous,” Raquel says. “He has a sense of humor. Besides which, I think he’s one of the only people in Washington who know what the hell’s going on in the world. Government”—she shakes her head sadly—“God help us, I suppose.”

Raquel takes another cigarette and Terry extends his lighter.

“What we need,” she says, leaning toward the flame, “is some commitment.”

Terry turns up his hands, indicating helplessness in a fickle world.

“C’est la vie,” he says.

“C’est la bullshit,” Raquel says. Her features are hazy with cigarette smoke.

“There is something not right with the world. The Government is supposed to serve the people, but now all people expect from the Government is to be fucked over. Things are not what they should be.”

‘“Things never are,” Terry says.

“Listen,” Raquel says, “I think fucking people over has become the national pastime. It’s all you see. God knows, when you get down to it, that’s what the movie business is all about, fucking people over. People in the business can’t let it go at simply being involved with their profession or performing better in their job. That’s too ticky-tacky. You have to get crazy about it. You have to draw your salary at the expense of somebody else. Somebody’s got to drop dead so you can breathe their air. If so-and-so gets one point two million dollars for a picture, then you have to get one point three million dollars. Just like that. Where’s the commitment?”

“Tell you what it’s time for,” Terry says. “Time we had women running things, for a change. Break the chain of male command, and so forth. I don’t think women would be as likely”—he raises his eyebrows and smiles—“corrupted by power. How’s that?”

“Oh, Terry, really, you have such an exalted idea of women,” Raquel says. She shakes her head from side to side. “You’re absolutely Victorian in that regard.”

“No, come on, now,” Terry says. He raises his hands, as if in surrender. “Name me a woman who’s acted tyrannically and exploited power the way male politicians do. Name me one.

Raquel looks at the table for several moments.

“Marie Antoinette,” she says finally.

“Oh, now you’re picking one case in thousands,” he says in a small shout, “and it wasn’t even that she was exploitive, poor dear, she just had such a hallucinatory outlook on life—”

“No,” she says firmly.

“No?” he says. “What do you mean, no?”

“No.” She points her finger at him, nailing it down. “Believe me, Terry, no. If it doesn’t happen frequently, that’s because women aren’t in positions of power frequently. That’s all. Women are capable of being just as vile and deplorable and treacherous and unscrupulous—”

“Ohhh,” Terry says, moaning. “You’re ruining my whole day, luv.”

“Don’t you think I know what I’m talking about?” Raquel says. She spreads her hands in a pantomime of candor. “This is me, Terry, this is Rocky. Believe me, there’s nothing inherently moral about being a woman.” She laughs suddenly.

“Terry, you are absolutely unreal. You are a gentleman to a fault.”

She throws him a kiss off the tips of her fingers. He bows his head in return.

“Tell me something, Rocky,” Terry says. “What would you do if you had a tremendous amount of money to spend any way you wanted? Do anything at all.”

“How much,” she says, “is a tremendous amount?”

“Oh … three million dollars, say. Four million. Doesn’t matter. Whatever seems like excess to you.”

“Three million dollars,” Raquel says. She pulls at her lower lip. “Jesus, I mean, it would depend on so many things….”

“Well, just think.” Terry says. “You know, would you buy an airplane, for instance? A yacht? A fleet of yachts? Just think of yourself.”

“Probably, I’d buy film properties,” Raquel says. She thinks about this a moment.

“Yes, that’s what I’d do.”

“All right, good,” he says. “What else?”

“What else? Well, I, Christ, I can’t even think … you know, three million dollars isn’t as much as it used to be.”

“OK, then, ten million,” Terry says. “It doesn’t bloody matter, Rocky. I’m just trying to find out how you would indulge yourself. Come on, be a good girl.”

“Well, I told you. I’d buy properties. Isn’t that what I’d do, Mary?”

“Yes,” Mary says, nodding in agreement. “That’s what she’d do, Terry. That’s what she talks about.”

“Yes, but”—he looks about him with exasperation—“but how the bloody hell many film properties could you buy? I mean, let’s say that’s all taken care of. Let’s just pretend, pet, you know, like the movies—”

“Terry, this is so incredibly boring, I …” Raquel says, raising her hand to cut him off. “No, wait. I’m thinking. I’m thinking. All right … let’s see.” She thinks. “OK,” she says. “First, I’d probably set up trust funds for my kids, so that they’ll be OK, but, well, now, there’s something I feel funny about. You know, kids who have money in the bank waiting for them … I don’t dig that that much. I don’t think it’s the best thing in the world, but that would be one thing I’d do.”

“OK, take care of the kiddies,” Terry says. “There’s a good mum. What else?”

“Whatever else seemed necessary at the time,” Raquel says. “I suppose I’d buy a house for my parents, and maybe a flat for myself in Paris, or a place in … I don’t know, Acapulco or someplace … I just don’t know, Terry. The idea of a lot of money isn’t all that interesting to me. If I had a lot of money to spare, I’d direct it toward my craft. I know that upsets you in some way, but that’s what’s most important to me, to improve myself as an actress. If I can do that, then I’m happy. Isn’t that what money’s supposed to buy?”

“Happiness?” Terry says. He scratches his head. “Possibly. There are conflicting reports. How about you? Are you happy?”

“Yes,” Raquel says. She raises her hand, preparing to elaborate, then has an afterthought and lets her hand slide back onto the table like a kite losing wind.

“Yes,” she says again.

“What have you done in the past, oh, year or so that you’ve really approved of? What’s been the thing that you could look back at and say, ‘There … there I am, God love me’?”

Raquel closes her eyes and purses her lips. From somewhere in the restaurant, there is a rush of communal laughter.

“I’ll put it like this,” she says at some length. She opens her eyes and focuses on the edge of the table. “I think I can honestly say that for the past couple of years, I’ve been happy with myself and with what I’ve done. I can look back at that time and not see anything that would make me scream.”

She shifts in her seat and draws a breath; she appears unaware of the sound of her voice.

“That’s not bad, you know,” she says, “being able to look back without wanting to scream. It’s something different.”

Terry watches her closely; his silence seems to hold the potential for comment, but he says nothing.

“I’m working at what I want to do and nobody has their foot on my neck. I don’t get crazy anymore. I’m not obsessed.”

“It’s the better way,” Terry tells her.

“It’s not bad,” she says. “OK, and not bad. I don’t have to tell you that it’s been worse.”

“Whatever the past is,” Terry says, “it’s gone and done with. Fuck whatever. You know what you want.”

“I don’t want anybody’s sympathy,” Raquel says. “I don’t give a damn about that. Just let me be, let me do my job. There’s nothing wrong with that.”

“Look, Rocky,” Terry says.

“Jesus, what do people want, anyway?” Raquel says suddenly. She discovers Terry’s hand resting on her own. “It’s not my problem what they think about me. They think whatever they want. Why should I have to pay for that? You tell me why. You tell me why I should have to pay for that.”

“Do you believe that?” Terry says.

“Believe it?” Raquel says. She laughs dangerously. “I’ll tell you. What happened to me two years ago, when I did that picture in France, that was the bottom of the barrel. That was the gutter. I told myself that I would never let myself be vulnerable to that sort of humiliation again. And that’s when I found out how you have to pay for what people think. You know what I’m talking about, Terry, this isn’t a misunderstood sex-symbol thing. That’s for the magazines, the hell with that. This was ugly, hateful violence. There was this little director who was going to show everybody that he was a big man by beating up the girl with big tits. You saw what I looked like; you took the pictures. I was going to sue the bastard.”

“Every business has its sick side,” Terry says. “You said it yourself about the movies; it’s not a delicate profession. Neurotic people calling themselves artists. Telling the world how sensitive they are. Bloody lot of crap. For most of them, their sensitivity doesn’t go beyond the crotch.”

“Sick,” Raquel says. She spits out the word. “Spoiled children running around making a movie. A lark. Everybody trying to outdo one another, each one trying to be more on top than the next.”

“All those stars, all those egos.” Terry says. “It couldn’t have been any other way.”

“It made me feel dirty about what I do for a living,” Raquel says. “All these power plays, all this bullshit … where’s the justification for that? Jesus Christ, it’s just a job; that’s all it fucking is, just a job. You go where you’re told to go, you say the lines, you do your work, you cash your check and you go on to something else. That doesn’t make you any different from the next person.”

“It shouldn’t,” Terry says, “but it does.”

Raquel lights another cigarette and smokes it in silence for several moments.

“In a way, it was funny,” she says at last. “After I’d left and gone to Paris, I read the accounts in the papers. All about temperamental Raquel. Isn’t that a joke?”

“Let it go,” Terry says to her quietly.

“They said how unprofessional I was,” she says, ignoring him. “How I’d walked off the set in the middle of the picture. Middle of the picture, my ass. That shithead came into my room when I was packing to go home—after we’d finished, mind you—and he told me that I couldn’t go until he told me I could go. Until he told me, can you believe it? Well, I told him to go fuck himself, politely, and I picked up the bag and started to leave. And that’s when he hit me. And he kept on hitting me.”

She makes her hand into a fist and grinds it against the edge of the table.

“He wouldn’t have tried anything like that with anybody else on that film. But he’d do it to me. He sure as hell thought he could do it to me. Do you want me to tell you why? Do you want me to tell you?”

“Forget it,” Terry says. “I’m telling you.”

“He would do it to me,” Raquel says in a rising voice, “because of what I am. Because I’m Raquel, that’s why. Because I’m like the girl who’s slept with everybody in town, so you don’t have to bother with formalities when you take her out. That’s how you have to pay for what people think of you.”

She looks down at her hand, still a fist. She relaxes it slowly and spreads it flat on the tablecloth.

At a table across the way, there is a young man with a stylishly trimmed beard and tinted aviator sunglasses. He wears a tailored leather jacket over a faded denim work shirt. He slouches self-confidently in his chair, one arm draped over the back; a thin gold bracelet clings to his wrist. He stares openly at Raquel and smiles with pleasure.

Raquel leans her head back and looks at the ceiling. She takes both of her hands and rubs them across her forehead and through her hair. As she straightens in her seat, she sees the bearded man looking directly at her. For a moment, she is caught in his line of vision, like a deer in an automobile’s headlights. The man’s smile widens with relaxed familiarity.

“Looking fine,” he says to her across the distance.

Raquel seems startled; she pulls her eyes away and brings her hands to the sides of her face. She does not look up, but she hears the man’s laughter as she takes her cigarette and slams it into the ashtray.