The news out of San Francisco says Willie Mays is dead at 93, as if death can contain a virtuoso of his grass-stained, sweat-soaked magnitude. Death is a past-tense proposition and everything Mays did on a baseball diamond lives after him in the present tense. He runs full-bore through our memories, his cap flying off his head whether he is stealing a base, stretching a double into a triple, or making a catch in center field so vivid, so impossible that it seems YouTube was created for no greater purpose than to preserve it.

Mays hit home runs too, a whopping 660 of them, and he might have beaten Hank Aaron in the race to break Babe Ruth’s then-record of 714 if the Army hadn’t snatched him up for nearly two seasons. And then there were the homers he lost in the cold, windblown nightmare that was Candlestick Park. But while numbers are baseball’s primary measuring stick of greatness, they scarcely define the breadth of Mays’ impact on the game.

More than anything else, it was his derring-do – the big swings, the basket catches, the peals of high-pitched laughter – that made him a never ending source of joy. His every move spoke of the two seasons he spent in the Negro leagues, a teenager romping where Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson carved their legends out of the color barrier that Jackie Robinson ultimately brought crashing down. There was an effervescence to the way Mays played for the Giants in both New York and San Francisco, and he carried it with him to the streets of Harlem for the stickball games that became a prize photo-op. Though his teammates called him Buck, he was anointed the Say Hey Kid in newspapers and news reels. Somehow it fit.

The important thing is to realize how high in the baseball stratosphere Mays dwells, for that also gives you an idea of how deep the air pockets he hit were and how confounding his descent turned out to be.

But you never would have guessed it when he went without a hit in his first 22 times at bat for the Giants. This was in 1951, the year they summoned him from their farm team in Minneapolis as they chased the destiny Bobby Thomson would secure with his Shot Heard Round the World. Long before that homer sank the Brooklyn Dodgers, the slumping Mays sat in front of his locker at the Polo Grounds, head down, eyes filled with tears. One of Giants’ coaches told manager Leo Durocher he’d better get out there and do damage control.

Durocher – foul-mouthed, thin-skinned, colossally self-centered – was hardly the nurturing type. Only once before had he got his hands on a manchild with such vast physical gifts. Pete Reiser was all of 22 when he won a National League batting championship, but he played center field for Brooklyn with demolition derby passion, crashing into unpadded, unforgiving walls and collecting the stitches, broken bones and concussions that soon destroyed his career. The chief beneficiary of Reiser’s recklessness was Durocher, who managed the Dodgers then, but Durocher never did a thing to save Reiser from himself.

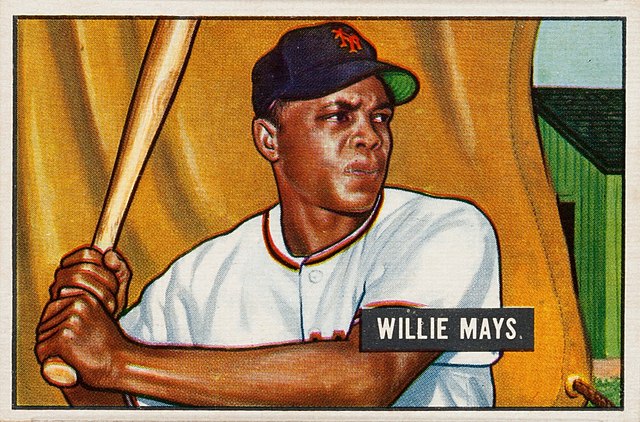

There would be no such human sacrifice this time. Durocher wrapped an arm around Mays’ sagging shoulders and dried his tears with praise and prophecies. No, Mays wasn’t going to be shipped to some salt-and-pepper league for more seasoning. He wasn’t going anywhere except back out to center field for the Giants, and Durocher didn’t care if he went 0 for 100. The kid from Alabama was going to win pennants and World Series – well, one World Series anyway – for Durocher, and Willie Mays was going to become such a great ballplayer that boys who got his trading card would cling to it long after their mothers had thrown away all the others.

Damned if Durocher wasn’t telling the truth. All of baseball realized it when Mays returned from the Army in 1954 to lead the league in hitting and triples and to make the catch people will talk about for as long as baseball is played, always in present tense.

It’s his first game on the sport’s biggest stage, the World Series, top of the eighth inning, score tied 2-2, two Cleveland Indians on base. A bruiser named Vic Wertz bashes a drive destined for the wide open spaces of center field in the Polo Grounds, a ballpark shaped like a geometric experiment. Giants fans are thinking triple, maybe even inside-the-park homer, afternoon ruined. Mays is thinking he can catch any ball that doesn’t clear the fence. He wheels and hits top speed like a Maserati coming off the line at Le Mans, calculating longitude and latitude as he tracks the ball to the exact spot where he makes an over-the-shoulder catch without breaking stride. He stops on a dime, spins and uncorks a perfect throw to keep the Cleveland baserunners from getting frisky. And a legend is born.

In 1982, when there was a hit song called “Willie, Mickey & the Duke,” it seemed only right that Mays’ name came first for more than musical reasons. Mickey Mantle of the New York Yankees and Duke Snider, a Dodger in both Brooklyn and Los Angeles, were Hall-of-Famers, just like he was, but Mays still seemed to occupy a galaxy all his own. The difference was best explained by Murray Kempton, the compassionate, polysyllabic cornerstone of the New York Post’s op-ed page, in a column 20 years earlier that described Mays joyfully tossing a ball into a crowd of souvenir seekers.

“All of a sudden,” Kempton wrote, “you remembered all the promises that the rich have made to the poor for the last 13 years and the only one that was kept was the promise about Willie Mays. They told us then that he would be the greatest baseball player we would ever see, and he was.”

That column was one man’s vote for Mays over Babe Ruth, who saved baseball from the taint of the Black Sox scandal by turning the home run into the engine that drove the game The Babe set World Series pitching records before he found his calling as an everyday slugger for the Yankees. And he became the first American sports hero to cast a shadow across the entire nation, a rollicking character with a cigar in his mouth, a hot dog in one hand, a glass of bootleg hooch in the other, and a bimbo on his arm.

You can argue the Babe versus Mays until clocks run backward. You might even champion Mays one day and Ruth the next. The important thing is to realize how high in the baseball stratosphere Mays dwells, for that also gives you an idea of how deep the air pockets he hit were and how confounding his descent turned out to be. The Giants’ move to San Francisco in 1958 was no easy thing for him. In New York he was revered. In his new home he was an out-of-towner no matter how thrilling he remained on the diamond. San Francisco wanted heroes it didn’t have to share, and soon Willie McCovey, Orlando Cepeda and Juan Marichal were making local hearts beat faster.

Mays wasn’t rejected as much as he was left to himself. If he thought it would be different when he returned to New York to play for the Mets in 1972, if he thought he could recapture even a portion of his youth there, he was wrong. He was still an old man by baseball standards, and when he had to take batting practice with the team’s youthful benchwarmers, he could be heard muttering about the “fuggin kids.”

Age caught up with Mays for keeps a year later in the glare of the World Series. He stumbled around center field like a man who couldn’t find his keys and the nation covered its lonely eyes. Then he packed up the mementoes of 22 years – the .302 lifetime batting average, the three 50-homer-plus seasons, the 12 Gold Gloves, the record 24 all-star game appearances – and walked into the first stage of past-tense life. There would be a statue of him in front of San Francisco’s new ballpark, casino work that got him in trouble with the lords of baseball, even a GQ cover with his godson Barry Bonds, the game’s new home run king thanks to the magic potions that weren’t there for Mays.

Life would never again be what it had been. But a year into retirement Mays was struck by the realization that some days could still be diamonds. He was in Baltimore fighting a cold and signing autographs none too happily at the house where Babe Ruth was born. When there was a lull, a uniformed Baltimore cop shyly stepped up to Mays. “Remember me?” the cop said. “You used to call me McCookie.” Mays stared at him blankly until the cop explained that he had been the minor leaguer who had taken over center field for Mays in spring training games. “Oh, yeah, I remember you now,” Mays said. And for just a few moments he was young again.

[Photo Via: Wikimedia Commons]