One of the favorite things of Vince Lombardi, coach, general manager and spiritual leader of the world-champion Green Bay Packers, is the grass drill. He lets an assistant coach lead the bending and stretching exercises, the calisthenics, but he himself must run the part of the drill that turns grown behemoths into groveling, gasping, sweat-soaked, foamy-mouthed animals without breath enough left to complain. It is a simple drill best conducted in the summer sun at brain-frying temperatures because sane men will not do it. The crazy men run in place, double time, as hard as they can, while Vince Lombardi shouts at them in his irritating, nasal, steel-wool-rubbing-over-grate voice. “C’mon, lift those legs, lift ’em. Higher, higher.” Suddenly he yells, “Front!”, and the players, who averaged $41,000 each for fourteen football games last season (there also were two post-season games), many of them no longer boys, but men in their thirties with families to care for and paunches to battle, flop on their bellies and as soon as they do, even while they are falling, Lombardi shouts, “Up!”, and they must leap to their feet, running, running, faster, higher. “Front!”, and they are down. “Back!”, and they roll over on their backs. “Up!” Run. “Front!” Down. “Up!” Over and over, always that raucous voice, nagging, urging, demanding ever more from rebelling lungs and legs. “Move those damn legs. This is the worst-looking thing I ever saw. You’re supposed to be moving those legs. Front! Up! C’mon, Caffey, move your legs. Keep them moving. C’mon, Willie Davis, you told me you were in shape. Front! Up! C’mon, Crenshaw, get up. It takes you an hour to get up. Faster. Move those legs. Dammit, what the hell’s the matter with you guys? You got a lot of dog in you. You’re dogs, I tell you. A bunch of dogs. Let’s move. Front! Up! For the love of Pete, Crenshaw, you’re fat. Ten bucks a day for every pound you don’t lose. Crenshaw! It’s going to cost you ten bucks a day. Lift those legs!”

The sound of their panting—seventy men reduced to sodden football suits filled with quivering muscles—rises over them in a moist, squishy roar. As the drill goes on the noises they make breathing almost drown out the sound of Lombardi’s voice. The breathing becomes louder and somewhat wetter, until it sounds like the ocean when the last wave rolls up into the sucking sand. Finally, when they are beyond the point of humanity or sanity, Lombardi lets up. “All right,” he shouts. “Around the goalpost and back. Now run!”

“That’s when you hate him,” says Henry Jordan, bald at thirty-two and looking older. A defensive tackle, he has been with the Packers since 1959. He knows what Lombardi does to his players when they report in the summer, so for three weeks in advance he works out, hard, pushing himself. It is never enough. “He drives you until you know you can’t go on. My legs just wouldn’t come up anymore. When he walked by me he hit them. He pushes you to the end of your endurance and then beyond it. If you have a reserve, he finds it.”

Sometimes he bulls past the reserve. Leon Crenshaw, a graduate of Tuskegee, is an amiable young man who didn’t mind being called Super Spook when he played minor league football with the Lowell Giants last season. But he was met with enmity by Lombardi because he showed up with three hundred fifteen pounds arranged paunchily over his six-foot-six frame. The coach said a pound a day or ten dollars. Crenshaw opted the pound. That was Wednesday morning.

Thursday noon he is lying, semiconscious, moaning, on a bench outside the St. Norbert College cafeteria where the team eats its meals during training. He has severe cramps and a doctor is rubbing ice over his ample middle while waiting for an ambulance. The other players, as they come out of the cafeteria, some of them sucking on toothpicks, avoid looking at him. It’s as though he were lying in a doorway in the Bowery or had fallen, a victim of plague, in a Bombay street. The diagnosis is heat prostration. But one of the players says he knows what it really is. “Starvation,” he says. It doesn’t matter which: Leon Crenshaw does not make the team. This is the Vince Lombardi process of natural selection. It’s how you build a professional football dynasty.

Partly how.

It isn’t enough to survive the tortures of the grass drills. One must enjoy them. So each time a fiendish new drill is announced, the players, college men every one, clap their hands in childish glee. They applaud. “Oh, yeah,” they shout. “All right. Allll ri-ight.” And they applaud.

Jordan laughs. “It’s like he says.” He digs at a sore muscle in his back and grimaces when he finds the right one. “If you aren’t fired with enthusiasm, you will be fired with enthusiasm.”

Another way to get fired is to come late to meetings or practice. And arriving on time isn’t enough. This would not show proper enthusiasm. So the Packers say there is Eastern Daylight Time and Central Standard Time and Greenwich Time and then there is Lombardi Time. “This is Lombardi Time,” says Don Chandler, the elderly kicking specialist who has been in the league eleven years. He points to his wristwatch. It is set fifteen minutes ahead. “If you come ten minutes early they’ve started without you.” Or the bus is gone. Or practice has started.

The players have bent to Lombardi’s will with a will and they have taken his spartan attitude as their own. Says Dave Robinson, a large linebacker who wears a mean scowl most of the time, which is all right because he’s that kind of football player: “If you come ten minutes early they make you feel like scum for holding them up.”

Now Donny Anderson, a Viking type from Texas Tech who got, it is said, $600,000 as a bonus when he signed a year ago, whispers to a veteran player on the sidelines of the practice field: “Slip me some water.” The veteran laughs. “There hasn’t been any water around here in eleven years.” Not true. There are perhaps six pints for the seventy huge players who will spend a violent two hours under a summer sun. But if Lombardi sees a player drinking water he shouts, “Whaddaya want to get, a bellyache?”

“C’mon, you lard asses,” Coach yells. (The players, most of them, call him that—Coach. Not the coach, but Coach, as in “Coach doesn’t like anybody hanging around the ice bucket.”)

Sometimes, during a scrimmage, one of the defensive units is allowed to come up for air. The players sit and watch Lombardi driving, driving, driving and they talk about the kind of coach they would be. They agree tough is best. “I’d be a bitch,” says Robinson. He thinks for a moment. “But that Wood.” He shakes his head sadly. Willie Wood is a five-foot-ten defensive halfback who plays football as though he had been shot out of a gun. “Wood,” says Robinson, “he’d be a mother.” The other players laugh.

The team has learned, too, to feel about injuries the way Lombardi wants them to. “Every week there are the injuries,” Lombardi says. “It is foolish to think that, the way this game is played, you can escape them, but every week I feel that same annoyance.”

Annoyance? Anger. Rage even. Players are afraid to get hurt. When they do, they try not to react to the pain. They pound the grass with a fist and say, “Oh dammit, dammit.” They react to being hurt, not to the hurt. They rail at fate, not at pain.

It began the first day in 1959 that Vince Lombardi, the man from the East with the odd New York accent and hot eyes the color of smoldering chestnuts, walked into the trainer’s room after he had taken over the failing fortunes of the faltering Packers. There were, he remembers, fifteen or twenty players waiting for the diathermy or the whirlpool or to be worked on by the trainer. “What the hell is this?” Lombardi roared, his big yellow teeth with the wide spaces between them making him look like an angry jungle animal. “You’re going to have to live with pain,” he told them. “If you play for me you have to play with pain.” Lombardi glared at the players, who looked like kids caught with their hands in the jam. Now they don’t even like to talk about injuries. They sidle up to the trainer and, in whispers, ask for a muscle relaxer, a pain-killer. If Lombardi notices them taking a pill he rasps, “What’s the matter with you?”

“Not a thing, sir. Salt tablets.”

Lombardi never stops trying to prevent injuries after they happen. On this ill-tempered summer day on the steamy practice field in Green Bay, Wisconsin—across the road from Lambeau Field, where the Packers play their games—Lombardi has been on his players hard. “C’mon, you lard asses,” Coach yells. (The players, most of them, call him that—Coach. Not the coach, but Coach, as in “Coach doesn’t like anybody hanging around the ice bucket.”) “What are you guys doing? For Crissakes, you look like you’re playing mumblety-peg out there.” The players are in full football regalia (making them all look like Boris Karloff in Frankenstein) under a relentless sun and they are practicing pass patterns, which means it’s offense against defense and the blocking on the line is serious. You can tell it from the slap of forearm pads as the defensive line whacks away and the strangled sounds that men make when others charge into their necks, football helmets first.

There is a pileup and out of the bottom of the pile comes a cry that has been torn out of a man’s throat, a shriek of agony. It’s Jerry Moore, a rookie guard, who hasn’t learned he is not supposed to cry his pain. The pile untangles and Moore is left writhing on the ground, his hands grabbing at a knee which is swelling so fast that in another minute the doctor will have to cut his pants leg to get at it. “Get up!” Lombardi bawls, the thick cords on his heavy, sun-browned neck standing out with the effort. “Get up ! Get up off the ground.” The sight has insulted him. He is outraged. “You’re not hurt. You’re not hurt.”

Minutes later Marv Fleming, an end who has been with the Packers four years, has somebody fall on his arm and separate his shoulder from the rest of him. He knows enough not to make any noise. But he lies there for a moment summoning the courage to take the pain he knows will wash over him when he stands up. Lombardi is otherwise occupied for the moment, but the players get on him. “Get up, Fleming,” one yells. “Oh, poor Fleming,” shouts another. “Stop killing the grass, Fleming. Get up.”

Ken Bowman, the center, three years with Green Bay, limps over to the trainer. “What you got for blisters?”

Lionel Aldridge, defensive end, four years a Packer, overhears. He snorts. “Nothing,” he says. “More blisters.”

That is the spirit of the Green Bay Packers. Lombardi instills it—relentlessly.

Jerry Kramer is thirty-one years old and is in his tenth season at Green Bay. Six-foot-three, two hundred forty-five pounds, rated one of the best offensive guards in the business, he is handsome in a football-player way, not pretty like Frank Gifford, but handsome, with light eyes that glint with the amusement he finds in the ridiculous world around him. Through the years he has been battered and scarred, probably more than most, and there is a line of angry hem-stitching up the back of his neck and head, the result of an old spinal injury. The players are kind about it; they call him Zipper Head. “In 1962 I was banged up around the chest,” Kramer remembers. “I was out for about two plays. I didn’t know it at the time, but I had two broken ribs. I played anyway. The next week, all I can remember is Merle Olsen of the Rams making cleat marks up and down me all afternoon. After that game we took X-rays and found out about the ribs. I went to Coach and told him I had been playing with two broken ribs and he said, ‘No shit? Well, they don’t hurt anymore, do they?’”

Elijah Pitts, who can run a hundred yards in 9.6 seconds and can take a football through the hole in a needle: “I had a shoulder separation. In college I wouldn’t have dreamed of putting my uniform on. Here I didn’t dare tell him I had it. I was afraid to tell him. I played two games with it.”

And Ray Nitschke. He is an odd-looking apple, a picture, a caricature of a fierce linebacker. His front teeth long since have been knocked out and he plays without his removable bridge so that when he smiles he looks gummy and evil. He is only thirty years old, but he is bald and when he pulls off his helmet his fringe of wispy red hair stands straight up, like fur on a frightened cat. He is a bulky man and you understand, viscerally, that he would like to hurt you. Off the field, though, transformation. His teeth back in his mouth, his hair combed, eyeglasses—he looks like a college professor. He even talks like a college professor. Many football players do. Even if they majored in basket-weaving (or, like the men on Syracuse’s great teams, Canadian geography) they’ve been exposed to four years of college, often five. It rubs off on them. Nitschke is in his tiny room, his bulk almost filling it, at St. Norbert’s Sensenbrenner Hall, the men’s dorm in this little college which is tucked picturesquely into a bend of the beautiful Fox River. St. Norbert is in West De Pere (pronounced, of course, de peer), six miles from the practice field and now, at five-fifteen after a day of muscle busting, Nitschke is sprawled on one of the two narrow beds in the room, waiting for dinner time and for the evening skull sessions in the basement. He tells about the time the tower fell on him.

There is a twenty-foot tower in the center of the three fields the Packers practice on. It’s for news photographers and, more important, Lombardi’s own cameraman. Football people film everything and Lombardi films everything plus one, including pass drills. He is said to have 16mm eyeballs. (When the assistant coach came back from his honeymoon he was asked how it was. “I don’t know,” he said. “I haven’t seen the films yet.”) On this day a sudden gale came up and the tower tilted in the wind and then toppled. It pinned Nitschke. One of the bolts crunched through his football helmet and he wonders what would have happened had he not been wearing it. He was lying under the twisted steel when Lombardi ran up. “Who is it?” he asked. Nitschke. “Aw,” said Coach. “He’s all right.”

Alex Hawkins who was drafted by the Packers but cut before the season began, and who has played with the Baltimore Colts and the Atlanta Falcons, said: “No one went into the training room for the first couple of weeks Lombardi was there. If anybody went, he wasn’t a Packer long. I’ve seen some injuries that would put players on other clubs into the hospital, but these Packers wouldn’t even ask for an aspirin.”

In his book, Run to Daylight!, which was written in 1963 with W.C. Heinz, Lombardi says he got it all from his father, Harry, an immigrant Italian butcher who settled first in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. Vince grew up in Sheepshead Bay, which must have been as tough as his father. “No one is ever hurt,” Vince Lombardi says Harry Lombardi always said. “Hurt is in your mind.”

Perhaps it was Lombardi’s father, too, who told him that playing with pain builds mental toughness. Or is it mental toughness that enables you to play with pain? Either way, mental toughness is one of Lombardi’s little dogmas. He has others:

Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing.

If you can accept losing, you can’t win.

You’ve got to be mentally tough.

Everything is “want” in this business. The man who wants to play is the man I want.

If you can walk, you can run.

Fatigue makes you a coward.

There’s no substitute for work in this business.

What the hell are you limping around for?

Dammit, get up, you’re not hurt.

The players like to kid, gently, about his slogans. They tell the story that once Lombardi said to his wife, Marie, “This damn knee is acting up on me again,” and his wife said, without a blink, “You’ve got to be mentally tough.” And they like to say that Coach wouldn’t talk to his wife for the rest of the week.

“Coach Lombardi is an intense, driving, striving perfectionist. He drives everybody—right down to the assistant trainer. I know he’s got me brainwashed. Unless I have a perfect day I’m upset.”

Whatever Lombardi means by mentally tough, a player has to be it just to stand the abuse. There are coaches who cajole. There are coaches who are fatherly. There are coaches who are merely coldly professional and demand their players be the same. Lombardi is hotly insulting. All the time. If a player can’t take it, if he doesn’t respond with ever-increasing effort, Lombardi trades him for a draft choice. Then he tests the new man. Henry Jordan: “Coach is fair. He treats every man the same. He treats us all like dogs.” On the practice field Lombardi says:

“You’re stupid. How the hell did you get so stupid?”

“You missed that block. You missed the block. Do it over. Do it again. You stay out here and do it all day.”

“Where the hell is the blocking in the middle? What the hell are you thinking there, Bowman?”

“What the hell are you limping about this morning, Williams? Get the hell out of here and don’t come back until you can run.”

“For Crissakes, can’t you block anybody?”

“Get in there, Mankins. Don’t just stand there. Don’t you understand what I’m asking you to do? Are you that stupid?”

“Dammit, Williams, you’re not running. I said into the hole, not around end.”

“You’re not hitting. All you’re doing is hitting and sliding. Go into him.”

“All right, Reed—after practice, you take two laps.”

And seldom is heard an encouraging word.

Max McGee, the tall, also balding end who has played eleven years of professional football, who was 1A to Paul Hornung’s 1 in the pro football camp-follower’s derby and the man who helped break up last January’s Super Bowl game with a super catch: “Sometimes I wonder about the way he pushes people. I really wonder about it.” He shakes his head and shrugs his shoulders.

Says Kramer: “Coach Lombardi is an intense, driving, striving perfectionist. He drives everybody—right down to the assistant trainer. I know he’s got me brainwashed. Unless I have a perfect day I’m upset. He says to me, ‘Boy, that stinks,’ and I say, ‘Yes, it does.’ I can’t think of a football game in ten years I’ve been satisfied with. When he says you look like a dumb ass, you feel he’s right. I remember one year, ’62, I was really busting ass. And he tells me, ‘We got the worst guards in the league.’ I told him he’d better draft some guards because I’d had it. He had me all screwed up. He would call me an old cow and say I looked like homemade horseshit. I really believed I was the worst football player in America. Then when the polls came out I was voted all-pro by the A.P., all-pro by the U.P.I., and then All-Star. I couldn’t believe it. I thought they were all crazy.

“Later on I got to talking to Jordan about it and what we decided was this. Lombardi was a line coach. I’m on the line. He was an offensive line coach. I’m on offense. When he played he was a guard. I’m a guard. Not only that, he was a right guard. He was on me more than he ever got on anybody.”

Once in a while Lombardi goes far enough to upset his most pliant players. Such a time was before the Super Bowl, the first game between the champions of the National Football League, the Packers, and the upstart American Football League champions, the Kansas City Chiefs.

Lombardi has a standing roster of fines: breaking curfew, $500; late for meeting or practice, $10 a minute; anyone caught standing at a bar, $150. For the Super Bowl week in Los Angeles he did some adjusting. It was $2,500 for anyone who blew the eleven p.m. curfew and $5,000 for anyone caught with a woman in his room.

Obviously Lombardi wanted to win this one bad. So did the players. A winning share in the Super Bowl was worth $15,000. And the league prestige involved was of incalculable value. So it wasn’t the enormity of the fines that bothered the players, but that Lombardi thought it necessary to institute them. “I just didn’t think the rule had to be there,” says McGee. “It was the biggest game of our life. If you didn’t know how important it was you wouldn’t be in the Super Bowl. I’m a habitual rule breaker; so was Paul [Hornung]. But we were disappointed in Coach Lombardi. We knew how important it was. We were not about to break any rules.”

Nor does Lombardi seem inclined to salve the wounded feelings of his Hessians with large salaries. He permitted Jim Taylor, a running back of long experience and such power that it is said of him that he could gain six yards against the U.S. Treasury Building, to take his services to New Orleans after a contract dispute. There is a tale told, too, that before the 1964 season an attorney presented himself to Lombardi and said, “I am here to negotiate the salary of Mr. James Ringo.”

Ringo, an outstanding center, had long been a bulwark of Lombardi’s offensive line and was considered a Green Bay fixture. Lombardi asked the lawyer to excuse him for a moment. He returned to his office twenty minutes later. “I believe you have come to the wrong city,” he said. “Mr. James Ringo is now the property of the Philadelphia Eagles.”

And when, after Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale had banded together to extract huge salaries from the Los Angeles Dodgers, it was suggested to Lombardi that his players might do the same, the coach glowered. “If they come here in a group,” he said, “they’ll go out in a group.” Since then, other teams, notably the Cleveland Browns, have had collective bargaining problems. Lombardi has not. One doubts if he ever will.

“Lombardi meets each question like it was a stab into Packer territory and must be defended against,” Glenn Miller of the Wisconsin State Journal once wrote.

“I’ve been told that the Packers are among the lowest-paying teams in the league,” says Willie (he’d be a mother) Wood. “I don’t know if that’s true. [No comparison figures are available, but chances are it’s not true. The Packers probably pay about the same as most, although Lombardi admittedly does not like “star” salaries. However, for a team which wins the title so much, one would expect the salaries to be higher than most. They are not.] If it was true, it would be a bad thing. I often think I can’t possibly make enough money playing this game. That’s how rough it is.”

“In 1963 I had a hell of a contract fight,” says Kramer. “It got to be kind of touchy. I got what I wanted, but it discouraged me from trying again the next year. You think for two or three thousand, the hell with it. I suppose that’s what he’s after all the time.”

As tightfisted guardian of the exchequer, Lombardi did all he could to end the expensive war between the N.F.L. and A.F.L. At first he refused to pay any bonuses at all to closely-contested-for talent and continued to win anyway. But two years ago he shelled out a reported million dollars to get Anderson and Jim Grabowski, a fullback from the University of Illinois. This so shocked the little world of pro football that it was immediately speculated Lombardi had demanded—and received—financial help from the league. Not that he couldn’t afford to handle the burden himself. Green Bay, with its tiny population (about 65,000), gets as much from television rights— $2,000,000 a year—as do New York and Los Angeles. Lombardi was influential in making this arrangement.

The financial and artistic success of the Packers (Lombardi took a team that had won eight games in three years and in eight years won five divisional titles, four championships and one Super Bowl) has surrounded him with an aura of infallibility he wears with pride and evident enjoyment. When Lombardi says, “I’m no miracle man,” local people say he’s lying in his teeth—and knows it. As a miracle man, however, Lombardi finds himself at odds with the press, which often does not accept miracle men with proper awe. He is impatient with reporters who ask probing questions and likes to put them off by taking the offensive. “Why don’t you learn something about the game,” he is likely to snarl at a questioner who displeases him.

“Lombardi meets each question like it was a stab into Packer territory and must be defended against,” Glenn Miller of the Wisconsin State Journal once wrote. With the television boys, however, Lombardi is a pussycat. “Television spends a lot of money on this game,” he says. “It’s entitled to some privileges.”

Lombardi likes to say that there are two things in the world he really understands—people and football. There’s a third—money. At first he refused to be interviewed for this article, later relented somewhat, adding, “I have to be careful what I say to you. I’m getting $30,000 for an article from Look.”

On Lombardi’s practice field there is a chalked square around the camera tower and reporters, by his edict, are imprisoned within it. This is to keep them as far from the football players as possible. It worked so well in Green Bay that when Norb Hecker, once an assistant to Lombardi, took over as head coach of the new Atlanta club, he installed the magic square there. When reporters walked off the field and said they would not cover the club, management apologized and Hecker had to back off. But the Green Bay Press Gazette is hardly the Atlanta Constitution.

The coach’s most famous encounter with the press involved Taylor. It was an open secret that Taylor was playing out his option (a method by which a football player may release himself from contract peonage but which, in recent years, has become so difficult and expensive that few players attempt it). However, the story had not been printed, which is the sort of thing the sporting press is often guilty of. Finally, however, Ken Hartnett of the Associated Press wrote a story which told of Taylor’s decision and said that he had been influenced by the enormous bonus young Grabowski had received. Lombardi was furious. He counted the story as a plot to cause dissension on his team. He promptly barred Hartnett from the Green Bay dressing room. At this point, though, he ran afoul of League Commissioner Pete Rozelle, a public-relations-conscious man who understands the press’s value to a sport. Rozelle said it was league policy to bar no accredited press man from the clubhouse. Lombardi had to relent. This summer during training, however, reporters were told not to enter the clubhouse because it was “too crowded.” Nothing was heard from Rozelle.

Lombardi gets away with this sort of thing because he has enormous power in Green Bay; A New York reporter recounts with awe the time he got to a Green Bay barbershop at closing. Nothing closes more firmly than a Green Bay barbershop at dinner time, so he was turned away. Lombardi, who was in one of the chairs, recognized the reporter and growled: “Cut his hair.” The reporter got his haircut. “Now that,” he says, “is power.”

It’s as coach and general manager of the Packers that Lombardi exerts his real power. He runs a sort of fiefdom in Green Bay, complete with automobile dealers who thrust free cars on him just so he will be seen driving them. The Packers are, theoretically, municipally owned. In fact they are an autocracy, run by Vince Lombardi.

In 1949, when the team was floundering financially, more than $125,000 was raised in a statewide campaign, citizens buying non-dividend shares at $25 each. Last year the Packers made about $800,000 in profit after taxes and the money was dropped into a fund and invested for contingencies. The club has already spent more than $2,000,000 modernizing the stadium, clubhouse and offices and installing a heating system under the turf, and no one can foresee any contingencies. It does not take a C.P.A. to calculate the speed with which that kind of money—and more like it each year—can grow. And who’s in charge of all of it? Vince Lombardi, that’s who.

There is a town board of directors which is supposed to meet with Lombardi and discuss progress of the team, finances and related matters, but in recent years Lombardi has been so weighed down with his two hats of general manager and coach that he has not had time to attend the meetings.

For all of this Lombardi receives a huge salary. No one knows what it is, but some years ago he turned down an offer from Los Angeles which included $100,000 a year, a fully paid for house, a $100,000 life-insurance policy and a piece of an oil well.

Men of wealth and power often come under attack from those with less wealth and power, and Lombardi is no exception. “I’ve always thought the mark of a gentleman is how he treats people who can’t do anything for him,” says a man who once worked for Lombardi. “Coach, I’m afraid, is only interested in his own image and people who can help him.”

The coach is accused of being frigidly aloof to local people (and too friendly with visiting New Yorkers), overly starchy in a town where summer formal dress consists of short-sleeve white shirt and tie, boorish with his employees (“Get me a drink,” he says to people who have important jobs with the team, and neglects to add please or thank you), impolite even to his wife (at least once he bawled her out loudly on some frivolous matter—blocking his automobile with her own—in full view and hearing of a large group of local citizens), penurious with his help (he is said to run a tight ship in more ways than one; seems to enjoy pouncing noisily on an expense chit of $17 that he thinks should have been no more than $15), and autocratic with everybody around him (“Like him?” says eight-year-veteran Jordan. “I don’t even know him”).

Whatever it takes to be a successful professional football coach, however, Lombardi has. If he does not inspire love in his players, he does demand and receive their respect, even if this respect stems largely from the fact that he wins and that the two post-season championship games last season were worth $25,000 to each of his players.

Says Fuzzy Thurston, another of Lombardi’s balding veterans of the football wars, an agile if somewhat lumpy offensive guard: “No one likes to be humiliated, but this is a totally dedicated man and somehow you don’t mind it from him. He demands one hundred twenty-five percent from you and that’s the way he gets ninety-five percent. He’s always trying to reach perfection. I respect him and I feel I owe him a lot.”

Says Wood: “The harder you work, the harder it is to accept defeat. This is what coaching is all about. If Coach is on you it means he’s giving you attention, he must think there’s enough in you to make it worth hollering at you. I know if he doesn’t keep on me, especially about my tackling, I develop bad habits. I’ll tell you this: the man milks you. I’ve seen him take players we thought didn’t have it and by the time he gets through with them they do a terrific job. They’re afraid not to. He’s the general and we’re the privates. It has to be that way. You don’t go over his head because you can’t. There’s nobody to go to.”

Says Jordan: “When Coach got here we were losers. He got us into superb condition. We couldn’t believe how hard he was working us. But he was right. If you’re in shape physically you can be mentally tough, if I can coin one of Coach’s phrases.”

“Whenever there is enthusiasm, dedication and pride, invariably you’ll find a dynamic individual who is communicating it. That’s Lombardi.”

Says Robinson: “He’s built pride into us. If you lose you feel you’ve let down the town, your family, and Coach. If we go into the second half fourteen points down, our defense will make a solemn oath not to let them score again and the offense will make a solemn oath to score three times. And Coach is the catalyst. He puts you through hell, but what you feel afterward is that if you can go through that you can go through anything.”

Says Nitschke: “I’ll tell you what he makes us feel. That the losing game is never long enough. We always feel if we had ten more minutes we would have won. You go out there feeling you have to win, but you know you don’t do it just on Sunday. You have to earn it. Each man has to feel this as a person. That’s Lombardi’s singleness of purpose. He makes us unsatisfied because he’s never satisfied. We’ve won 49-0 and he’s not satisfied because we didn’t play a strong football game.”

Says Kramer: “Let me tell you about Lombardi’s spartanism. We had a guard, a fellow named Gale Gillingham. He was with the College All-Stars and when he broke his hand they dropped him and he came to this camp. He got here and he didn’t miss a scrimmage. He was treated as if his hand were perfectly normal. It’s like a baby bawling. If you don’t pay attention he’ll go about his business. Sympathize with him and he’ll keep crying. Sure, he treats us like children. But I think it’s with good reason.”

Says Willie Davis, 245-pound defensive end: “Whenever there is enthusiasm, dedication and pride, invariably you’ll find a dynamic individual who is communicating it. That’s Lombardi. Of course he can be difficult. I’ve always felt it would be impossible to play under him if you didn’t win. I don’t think I could take him. I used to feel you had to love a guy to work for him. I’m no longer so sold on this. The one thing that’s a must—a coach has to be able to reach the guys. And Coach is a great emotional lecturer. He can get you aroused, really start the old adrenalin flowing. Once, during the week after a bad game, I remember he said, ‘I just wish I had the chance to go out there and do it myself.’ Damn. I felt this man is so dedicated, so involved, that if he could do it himself it would get done and done well. And it’s too bad he has to depend on us. I felt, goddam, the least I could do was go out there and try.

“This man says things that challenge you. People think that a pro just does a job, but there’s a lot of emotion and desire involved. Money can’t buy that emotion and desire.”

Lombardi’s most vocal admirer on the team is Bart Starr, the first-string quarterback, who quietly and over a long period of time has become recognized as one of the best of a highly intelligent and talented group of N.F.L. quarterbacks. The son of an Army sergeant, Starr is a soft-spoken, self-effacing Alabaman who keeps a Bible by his bed. He takes all of Lombardi’s commandments literally. He never goes near the water bucket. He is almost never injured. (When he was injured at the beginning of this season, he played with great pain and so poorly that finally his uniform had to be stripped from him.) “All our success stems directly from Coach Lombardi,” Starr says in his sincere but somewhat marshmallowy way of speaking. “When he came here he changed our thinking from a negative attitude to a positive attitude and from a losing attitude to a winning attitude. This is the type of an attitude which you have to take into every game, into every scrimmage, every encounter, every encounter of life, as he puts it. He worked long and hard with us and showed us not only how to do things but the why of it. In so doing he changed the entire complexion of the team.”

Starr and Lombardi make an ideal combination in that the quarterback’s personality is properly recessive. When Starr is on the field it is as though he is an extension of Lombardi’s overwhelming ego. This is a remarkable symbiosis, one that few coaches attain, especially in a day when many plays are called not in the huddle but on the line of scrimmage in order to foil rapidly shifting defenses. “I like to feel that the job I’m doing on a Sunday afternoon is the job that he would do if he were playing,” Starr says. “I’m his representative. I want to call the ball game the way he would want it called. That’s what I’m striving to do all the time, to do the job he wants me to do.”

On appearance alone one would not think that Lombardi could inspire this kind of fanatical devotion in a Bart Starr. Vincent Thomas Lombardi, once alliteratively described by Time as a bristling, brooding bear of a man, looks rather more like an Italian papà than any other breed of cat or bear. Indeed, he looks like an Italian papà whose feet hurt. (In fact they do, which is why he wears those bulky soft-top shoes which are constructed over casts of his feet and so appear to have been designed to walk on water.) At fifty-four he has a bit of a weight problem and walks with his belly sucked in and his chest extended like a pigeon’s. Even so, the waistband of his beltless (but pleated) slacks sometimes folds over to show the lining—a problem of most middle-aged men in a world where all clothing seems to have been designed for Bobby Kennedy. His hair lies on his head in a series of tight waves and is powdered with grey, as are his heavy eyebrows. He appears to smile a lot, at least he often shows his teeth in what seems a smile. But often as not it is a nervous grimace. (Players on the Cleveland Browns have taken to calling him The Jap.) He is five-foot-ten and appears shorter in the company of the large young men whose fate he commands. When the players look down on him, however, it’s usually to say, “Yes, sir.” (“The best thing to do when he is chewing you out,” says one player, “is just be still. Mighty still. And remember to say yes, sir when he’s finished.”)

If this sounds as though Lombardi runs a sort of paramilitary organization it is only because he does. The man who had the single greatest influence on Lombardi’s life was Colonel Red Blaik, one-time football coach at West Point. Lombardi worked six years under Blaik at the Point and no doubt this is where he picked up his military bearing as well as a practice timetable which goes off with, well, military precision. This precision was enough, in the N.F.L., to earn Lombardi the reputation as an organizational genius.

“Red Blaik had a great deal to do with any success I’ve had,” Lombardi says. “He not only was a great football coach, he was a great man. I had great respect for him. He was a man of great principle, a great organizer. I learned many things from Red Blaik.”

What Lombardi also might have learned at West Point—and didn’t— is the danger colleges face when they act as farm teams for professional football. He was at the Point in 1951 when ninety cadets, more than a third of them football players, were expelled in a cribbing scandal. Yet to this day he says, “A school without football is in danger of deteriorating into a medieval study hall.”

Lombardi got to West Point by an indirect route. There was no football at Cathedral Prep Seminary in Brooklyn, which is the first step for those studying for the priesthood. (Asked what changed his mind and he says, “Oh, nothing.”) He transferred to St. Francis Prep, also in Brooklyn, and as a senior played one year of football. Then it was Fordham University in The Bronx, where he became one of the Seven Blocks of Granite, the famous line of a famous football team, making up in ferocity what he lacked in poundage. After graduating from Fordham and deciding that he wasn’t going to be an insurance investigator or a lawyer, Lombardi went to work as a high-school coach at St. Cecelia’s in Englewood, New Jersey. There he achieved a measure of fame by taking his lads through thirty-six games without a defeat, although in eight years there he never made more than $3,500 annually. His two kids know about being poor.

In 1947 Lombardi went back to Fordham as freshman coach. He stayed there more than a year, or long enough to see that football was dying at Fordham (and perhaps wonder why it wasn’t becoming a medieval study hall). Then it was West Point under Blaik (who recently described Lombardi as being “a thoroughbred—with a vile temper”). Lombardi took the job as offensive line coach with the Giants under Jim Lee Howell in 1954. He was slated to become head coach when Howell retired but Green Bay grabbed him and in 1959 Vince Lombardi had his own football team. After Howell retired the Giants tried to get Lombardi back, but he would have had a boss in New York. In Green Bay, he is it all.

At no point did Lombardi’s early parochial training desert him. He still attends mass every morning (and some players have noticed that it doesn’t hurt them to be seen by Lombardi making that scene) and when he talks of important things in this world he puts it family, church and football, in that order. Nor does he seem particularly out of place dropping to his knees in the clubhouse after a difficult victory and leading the team in an Our Father. “You wouldn’t think a professional football coach could get by with anything like that,” says a man who used to play for him. “But Lombardi does.”

“I’m a religious man,” Lombardi says. “I’ve got a great deal of faith in God, a great deal of dependency on God. I don’t think I’d do anything without that dependency. We don’t pray to win. I do think we pray to play the best we can and to keep us free from injury. And the prayer we say after the game is one of thanksgiving.”

My conversation with Lombardi took place on a Sunday morning after I had been in Green Bay for a week, the coach taking little notice of me except to ask, from time to time, if I were getting enough “stuff,” and to point out with great glee to his coaches that “there’s a real New Yorker” when he spied me reading a newspaper subway fashion, folded into eighths, and finally to sic his young publicity man, Chuck Lane, on me to see if there couldn’t be an arrangement whereby my quotes from the players could be inspected before publication. (There couldn’t. The request, given the climate of professional football, was not so presumptuous as one might think. Bud Grant, the new coach of the Minnesota Vikings, issued the following manifesto to newspapermen this summer: “Questions regarding player performance—be it individual, teammate or opponent— should be addressed to Coach Grant, not to players or assistant coaches. These are questions of evaluation and opinion and Coach Grant prefers to answer them himself.” In other words, talk to the football players about anything but football.)

I was particularly anxious to talk to Lombardi about three things: his method of building a team in his own image; his reaction to being called a William Gladstone of professional football, conservative to the point of boredom; and an attitude he had expressed about individual freedom as opposed to respect for authority in an address before the American Management Association.

During this talk Lombardi, who, given other circumstances, could have been a tyrant only to his own family, got off lines like these: “Unfortunately, it has become too much of a custom to ridicule what is termed ‘the company man’ because he is dedicated to a principle he believes in…. Everywhere you look, there is a call for freedom, independence or whatever you wish to call it. But as much as these people want to be independent, they still want to be told what to do. And so few people who are capable of leading are ready and willing to lead. So few are ready….We must gain respect for authority—no, let’s say we must regain respect for authority….We must learn again to respect authority because to disavow it is contrary to our individual natures.” This is not out of the memoirs of some South American general, it’s out of Vince Lombardi and he believes all of it.

Now, sitting in a little office in Sensenbrenner Hall, the birds making a racket in the trees outside, Lombardi was asked to explain. “I think the rights of the individual have been put above everything else,” he said. “Which I don’t think is right. The individual has to have respect for authority regardless of what that authority is. I think the individual has gone too far. I think ninety-five percent of the people, as much as they shout, would rather be led than lead.”

That’s what he said. It made me eager to change the subject to football.

The Lombardi method of football, he likes to say, is simple. It’s blocking and tackling. The thick and complicated play book that other teams’ players lug around is not one of the Green Bay players’ burdens. Lombardi likes to keep it simple. After the grass drill his favorite thing is the hole in the defensive line that his running back, digging in his cleats and churning up turf with an ankle-wrenching ninety-degree cut, can slide through as smoothly as a piston into a cylinder. “Beautiful,” Vince Lombardi will say of that hole in the line. “Just beautiful.” He will push his blunt-fingered hands into the back pockets of the football pants without pads that he wears on the practice field, tilt his head back and admire that hole as though he were standing in front of the Mona Lisa at the Louvre, and he will rumble, “Beautiful.”

Lombardi is so hung up on the discipline bit that he firmly believes that it counts more than talent. The talent in the league, he says, is almost even. The difference is in spirit and discipline.

Give Lombardi a back who can make five yards on every try and he will five-yard you to death. He did it with Taylor and Hornung, he was prepared this season to do it with Pitts, Anderson and Grabowski. He has been using the forward pass more in recent years, but only because the defenses have forced him to. At heart he is still a block of granite.

“You know what that damn team is going to do on just about every play,” says a rival coach. “But you can’t stop them.”

This tight, ball control football has been winning. Nevertheless there are many who think it’s dull football. One of these is Fran Tarkenton, the scrambling Minnesota quarterback who was traded to the New York Giants this season. Tarkenton said in Sports Illustrated not long ago : “…the way to beat Green Bay is to play it at its own conservative, careful game….In the last couple of years the Packers have raised their theory to the highest, emphasizing execution, sophistication and discipline and there’s nothing wrong with that. But there’s also a place for imagination and verve and flair, for improvisation, for breaking out of there and turning a busted play into a long gain and trying everything. Furthermore, I’ll go so far as to say that flexibility and mobility have N.F.L. history on their side, and Green Bay’s style is against the pattern of football history.”

Lombardi’s reaction to this is one of anger. “He’s using words, that’s all,” Lombardi said, coming close to spluttering. “It’s unfortunate they print things like that. Flexibility. Mobility. That’s mumbo jumbo. What does he mean? He’s talking about running around in the backfield. That’s not football, that’s sandlot. There’s no difference in our offense from that of any other team in the National Football League. I happen to get more enjoyment out of a well-executed running play than I do out of a well-executed pass play. When I first came to the league there was a great deal more passing than running. Now it’s about fifty-fifty for all teams. I take a great deal of pride that people have thought we’ve done well enough to follow what we have done.”

It’s possible to call Lombardi’s game something other than football. The word is discipline. “Football is a discipline game,” he says. “You have to have discipline to play it. Against what Tarkenton says, it’s not mumbo jumbo, flexibility, mobility. It’s discipline.” One could almost hear reveille being bugled at the Point.

Lombardi is so hung up on the discipline bit that he firmly believes that it counts more than talent. The talent in the league, he says, is almost even. The difference is in spirit and discipline. That’s where the coach comes in and it’s important to him, just as it’s important to have the name on his office door read Mr. Lombardi rather than Vince Lombardi and to have a Scotch around which calls itself V.L.

Most of his players agree with him. “He can take an average player and make a great one out of him,” says Herb Adderley, who is rated a great defensive back. The older players point to the fact that the nucleus of men he ran to fame with were already on the losing team when he arrived. But others believe that his talent is more in trading for draft choices than anything else.

“I disagree when he says the only difference between teams in this league is the work they do,” says Max McGee. “I honestly feel our personnel is better than everybody else’s.”

Probably it’s a combination. Lombardi gets the good players, many of them by shrewd swapping of draft choices. Then the ones who can’t stand his gaff, or who won’t bust a ligament trying to avoid a Lombardi chewing out, are traded off for more draft choices. The result is a Lombardi kind of team, a winning team. They win or else.

Which is why Paul Hornung tells this story on the coach. One night after a long, cold, difficult day on the practice field and in front of the movie screen, Lombardi came home late and tumbled into bed. “God,” his wife said, “your feet are cold.”

And Lombardi answered, “Around the house, dear, you may call me Vince.”

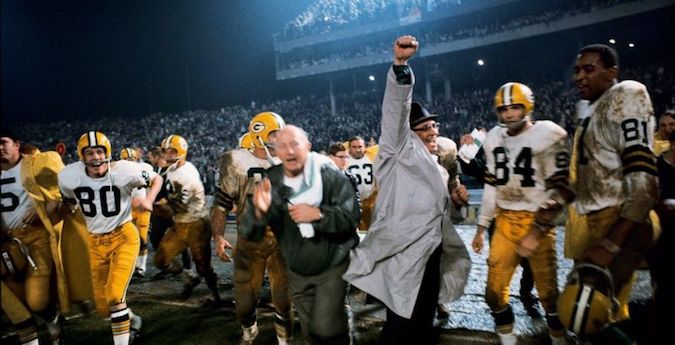

[Photo Credit: Neil Leifer via Taschen, featured in The Golden Age of American Football]