When Joan Crawford invited me to visit her in California, I should have had sense enough to refuse. However, curiosity led me to accept, although if I had known what I was letting myself in for, I wouldn’t have done so.

This was in June 1956. Esquire magazine wanted me to do a general article about Hollywood, because although I had been film critic of the Conde Nast magazine Vanity Fair, I had never been to the movie capital. Esquire was paying my expenses and arranged to put me up at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Thinking of people I might want to interview, I wrote Joan a note, saying that I was coming out and that I hoped she would be in town while I was there. To my amazement, she sent me a telegram asking me to wire her my telephone number in New York. (I suppose it never occurred to her that I might be in the telephone book.) I wired her the number and she called. She was enthusiastic, almost embarrassingly so. I told her I would stay at the Beverly Hills, “Oh, no you won’t!” she exclaimed. “You’ll stay with me.” I said that was very kind of her but that the hotel reservation had been arranged. “Cancel it!” she ordered. “What the hell? You’re staying with me. That’s all there is to it. Just wire me your flight and time of arrival.” And she hung up. “You know,” I said to my husband, “I think she sounded drunk.” He said it had probably been a poor connection. As events were to prove, my assumption was the correct one.

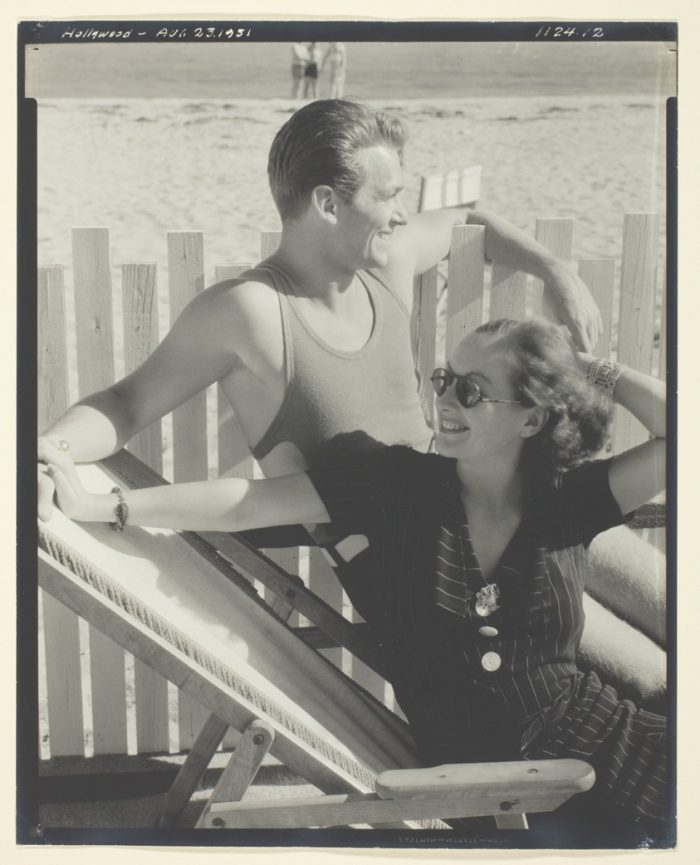

I had met her briefly in October 1935, when I was still on Vanity Fair. She had been having an affair with Franchot Tone, trying to keep it quiet because at that particular time movie moguls took a dim view of any scandalous publicity about the private lives of their glamorous minions. A standard clause in their con-h-acts referred ominously to “moral turpitude.” A big star like Joan—,and she was then one of the very biggest—,had to be careful in public even though the multiplicity of her sex life was notorious in private gossip, which included the rumor that in her earlier days she had been a hooker. (She was by no means the first or the last famous star of whom the same could be said.)

Eager to get away from their discreetly clandestine meetings in Hollywood, Joan and Franchot took a holiday in New York, both staying at the Waldorf. One of the tabloids published a diagram of their floor in the hotel, showing the location of their rooms, which were separate but, so to speak, vis-a-vis. Or perhaps side by side. Anyway, close enough.

That did it. The newspapers had a field day. Were they secretly married? If not, why not? Did they intend to get married? When? Joan gave a press conference, crowded with eager-beaver reporters who bombarded her with intimate and personal questions which she gallantly tried to field. I had to leave, so I went over to her and said quietly, “Don’t let them get you down. You’re doing fine.”

That evening I took my mother to the theater, and Joan and Franchot sat in the row in front of us. Joan recognized me and introduced Tone to us. A day or so later they were married in New Jersey, a wedding forced on them by the pressure of newspaper publicity and their studio, MGM.

I certainly didn’t expect that twenty-one years later she would even remember me, much less insist that I be her houseguest. I knew that in the two previous decades she and Tone had divorced; she had married and divorced Phil Perry, a handsome, unassuming young actor who played minor film roles; she had adopted four children (she had two miscarriages while married to Tone); and in 1955 she had married Alfred Steele, chairman of the board of Pepsi-Cola. She was one of the most durable, inextinguishable stars in Hollywood. When it looked as if her career might be on the decline, she bounced back with an Oscar as Best Actress of 1945 for her work in the title role of Mildred Pierce.

“I think the most important thing a woman can have, next to talent, of course, is her hairdresser,” she said one day.

She had never been one of my favorites, but I was intrigued by what I had learned from various sources about her early life. She was illegitimate, and in 1904 (which was the real year of her birth, not 1908, as she usually said) this was a shameful stigma, unlike today. Her background was one of poverty, abuse, and grinding toil. She had worked since she was eight years old; ironing shirts in a laundry; as servant, waitress, cleaning woman, telephone operator, bundle wrapper, salesgirl at the notions counter of a Kansas City department store, chorus girl, nightclub dancer. There were always men, and she learned how to use them. I had also heard about the “blue” movies she made for stag parties in her first Hollywood years. Or, to be exact, I had heard about one of them, called The Plumber, which she made with the comedian Harry Green. In those days pornographic films were so simple in their burlesque-show vulgarity that they were hilarious. Take The Plumber. The heroine telephones a plumbing shop. “I need a plumber to plug a hole.” Plumber arrives, “I’ve come to plug your hole.” Both get undressed at lightning speed and hop to it. It was a short, black-and-white, silent film, with subtitles and the jerky movements of early slapstick comedies.

When Joan was married to her first husband, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr, so the rumor went, she bought up every print of The Plumber, with one exception. That exception was owned by The Quiet Birdmen of America, a private club of aviators. (Lindbergh was a member.) The Quiet Birdmen refused to sell. If their print still exists, it should be quite a collector’s item.

This story, not surprisingly, has been denied, but I heard it way back in the thirties from people who were in a position to know. Together with other provocative anecdotes of her life, it made me curious to know Joan better and to try to find out what she was like beneath the grande dame image she worked so assiduously to create. How complete, I wondered, was the switch from the young girl who went to Hollywood in 1925 and became known as “The Hotcha Kid”? She had a toughness of inner fiber that enabled her to survive in the rough-and-tumble jungle of silent-film days and eventually to make the transition to talkies. No drama schools, no overnight success. She made it the hard way. She fought and finagled and fucked her way to the top. No one in those wild early years had more ruthless ambition for success than Joan, who worked for it like a demon, with no holds barred. She achieved it, not by any great acting talent, but by grit, relentless determination, good looks, a compelling personality, and absolutely staggering stamina. She would do anything—and she always did—to become and remain a Big Star.

My New York plane arrived in Los Angeles at 5:30 on a Tuesday afternoon. Joan’s secretary, Bettina, met me and drove me lo the house on North Bristol Drive in Brentwood. Joan was walking around the grounds, waiting for me. She wore gray slacks and a white, open-neck shirt. She was shorter than I expected. On the screen her presence is always so dominating that I was surprised to find that she was only five feet four and a half inches tall. Her hair was combed back from her forehead and she seemed to be wearing no makeup. She looked great, with her chiseled cheekbones and jawline, blue eyes, clear skin—where had all the freckles gone?—and the most beautiful nose I’ve ever seen.

The secretary left, and Joan took me into the house. It was a large Hollywood-Spanish ranch-type mansion. I’ve heard that it had twenty-seven rooms, but I saw only five: my bedroom, Joan’s bedroom, the kitchen, the drawing room, and a sort of den. There were no servants except Jenny, an elderly cook who was usually invisible (although I frequently heard Joan shouting at her angrily) and Jimmy Murphy, a short, fat man served as butler, maid (he was the one who made my bed and cleaned my bathroom), chauffeur, errand boy, and general dogsbody. He had once worked for Morton Downey, the singer, but had been with Al Steele for some time. Steele, away on business, left him to take care of Joan. There was no one else, except that friends of mine said that Joan’s mother lived in a back part of the house and was never permitted even to use the front door. No one ever saw her with Joan, nor did Joan mention her.

Murphy took my luggage up to my room, and then the three of us went to the kitchen where Joan poured drinks of 100 proof vodka served in huge glasses. She refused to let me have any ice, tonic, or water. Just straight vodka. Not even any ice. This was to be the pattern of the week. Whenever we were home, she kept the vodka coming, though I kept trying to pour mine into plants, flower vases, or down the sink, when she wasn’t looking. She kept a sharp eye on me most of time. Although I had told her that I was going to write a general article about my impressions of Hollywood, she obviously intended for me to concentrate on her. She spent hours showing me her clothes, including the nightgowns she had had made, chiffon shorties in different pastel colors, one for every night of the week. On the front of each was embroidered “Good morning, Alfred darling.”

“I’m a perfectionist,” she told me repeatedly. She was obsessive about her clothes, her makeup, her hair. “I think the most important thing a woman can have, next to talent, of course, is her hairdresser,” she said one day. It was a statement that left me speechless. She thought it was disgraceful that Anna Magnani had won an Oscar. “She looks crummy. No chic,” Joan said firmly. Never mind that Magnani was a superb actress, even a great one. “Her hair is always messy.” To Joan, that was what mattered. When she read a film script, the first thing she seemed to consider was what kind of clothes the part called for, and how many changes. A film critic once wrote, “Miss Crawford doesn’t so much play her scenes as she dresses for them.”

I not only had to look at her wardrobe, I had to spend one afternoon looking at the color transparencies and the snapshots of her honeymoon with Steele in Capri and their subsequent travels in Europe and elsewhere. There weren’t even people in most of them. Just buildings or scenery. We seldom discussed anything except her clothes, her films, her exercises. I didn’t see a book anywhere. She read only the Hollywood columnists, the film news, and the funnies. Wherever she went, on location out of town for a movie or traveling with Steele, she had the comics sent to her by airmail.

Then there were her Jewels. In the old Hollywood days the path of sex was usually traveled in cahoots with a lapidary. A woman like Joan wanted jewels, lavish jewels—and she got them. One afternoon she brought out a huge jewel casket and showed me the spoils it contained, some of which would have sparked a gleam in the eyes of Tamburlaine the Great, especially the enormous aquamarines and a dazzling contraption of magnificent diamonds—bracelets, necklace, broach, earrings—which could be hitched and unhitched to form different combinations, like some fabulous Mechano toy. Two or three bracelets could make another necklace: the original necklace could be divided into bracelets; broaches could be worn as pendants or vice versa, earrings as lapel clips, and so on, a blindingly bright, knock-your-eye-out mix-and-match set Steele had had made for her.

When she became an important star, it was said that she auditioned her leading men in bed. Some of those rejected claimed that they refused the boudoir aptitude test of even that they failed to make the grade.

Al Steele was neither young nor handsome. She surely wasn’t in love with him, although she put on an elaborate act. Their marriage had been a major coup for her, and she was intensely proud of being his wife. To her, he represented the real world, the world outside, in which he was a bigtime business power. Her other husbands and lovers had been connected with some aspect of “show biz.” When she became an important star, it was said that she auditioned her leading men in bed. Some of those rejected claimed that they refused the boudoir aptitude test of even that they failed to make the grade. In sex she was aggressive and domineering. At one time she desperately wanted to marry Clark Gable, but she couldn’t bring it off. At the beginning of their affair, he was still married to his second wife, Rhea Langham, a nonprofessional, and Joan was not yet divorced from Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. Later, Gable was also sleeping with Jean Harlow, and Carole Lombard was crazy about him. Joan tried her best to meet the competition, but in the long term Gable never would have tolerated her arrogant possessiveness. (It was Carole who got him, although their marriage of less than two years was not quite as idyllic as it is now made out to have been. The reason Carole went on her fatal, plane trip to sell World War II bonds was that Clark was having an affair with a famous Hollywood sex symbol. Carole knew it and was so miserable that she wanted to get away.)

But all this was on a different planet from the world in which Al Steele moved. Joan’s was the tinselly circus of entertainment. Steele was a multimillionaire of commerce, merchandising, international business empires. She met him through a mutual friend., Earl Blackwell, who was spending New Year’s Eve, December 31, 1955, in Las Vegas with Steele and Steele’s second wife, Lilian. Blackwell used to telephone Joan every New Year’s Eve, and this time he put Steele on the phone to talk to her, too. Slightly less than five months later, Steele and Joan were married. A Mexican friend of mine, owner of an advertising company that handled Pepsi in Mexico, had known Steele for many years. They were close friends before Steele left Coca-Cola for Pepsi, even before Coca-Cola, “I don’t think Al was really in love with her,” my friend told me a few years ago when I was in Mexico City. “He was madly in love with Lilian, but she left him and got a divorce down here. He married Joan on the rebound. She was a world-famous movie star and he liked to show her off. She went to Pepsi conferences and thousands of people came to gawk at her. But I think that if Al had lived, the marriage would have broken up. He was getting fed up with her imperious manner. She began to think that her role at Pepsi was more important than it was. She tried to run things her way. And she was so damn artificial. Nothing natural about her, nothing really human.”

When I was staying with Joan, she and Steele had been married a year. She telephoned him daily. When we went out, she left word for him, wherever he was, to be sure to call her wherever we were going: a restaurant, a costume fitting, a dinner party. Then she would insist on taking his call in front of everyone. “Don’t you want to take this in the other room, Joan?” our hostess, Jane Greer, asked on one of these occasions. “Oh, no. I’ll take it here,” Joan said, and we all had to listen, willy-nilly, to a stream of extravagantly intimate billing and cooing. “Oh, sweetheart, I miss you so! Oh, Alfred darling, I can’t stand it without you. I love you so much,” and so forth.

The most intriguing of these conversations was one in which she was pleading that he come home for Father’s Day. “But darling, Alfred my love, aren’t you coming home? Sunday is Father’s Day! The children want their daddy.” The baffling part of this was that there were no children in her house that week, nor would there be. This was what disturbed me most about her. It began on the day of my arrival.

The four children were Christina and Christopher, adopted by Joan when they were ten days old, and Cindy and Cathy, the “twins,” adopted at birth. Joan always said that they were twins, dressed them alike, made them call themselves twins. Actually, they had been born a month apart to different families. Anyone who didn’t know how Joan treated them would have said that they were four lucky kids. In reality, their childhood and adolescence were wretchedly unhappy. My first intimation of this was when the secretary, driving me from the Los Angeles airport, told me that Christina, then sixteen, had graduated that day from her Los Angeles school and had won a prize, Joan didn’t go. Instead, she sent the secretary. As a mother myself, with a daughter fifteen and a son nine, I was shocked by this. “But Joan is her mother,” I said, “As far as Christina’s concerned, she’s her real mother. Your mother always goes to your graduation. It’s not as if the school were in Europe. It’s right here. And Christina was getting a prize. I don’t understand.” The secretary just gave me a look and said nothing.

“Joan is a fiend with those poor kids,” one woman told me. “Poor Christopher got the worst of it. He’s run away from home several times because he can’t stand it.”

The incident worried me. I kept thinking about it. I kept picturing the graduation scene with all the other parents there, with Christina in her graduation dress, going up to receive her prize, and her mother had sent a secretary to the ceremony! After a couple of days and countless straight vodkas, I broached the subject to Joan. “Wasn’t Christina hurt that you didn’t go to her graduation?” I asked. “Oh, no,” said Joan carelessly. “She realizes how important my work is, that I have to go to fittings, as I did then.” “Couldn’t you have postponed the fitting?” “Certainly not.”

Murphy, the man-of-all-work, was there. Later, when Joan had left the room, he said to me, “She didn’t have a fitting that day. She was right here at home.” “Well, where is Christina now? Why haven’t I seen her? Why do I have her bedroom?” Murphy shrugged. “Better not to ask questions,” he said. “She’s been shipped off someplace. The children are almost never here. “What about Christopher?” “Don’t ever mention his name, poor lad. He’s run away from home a lot, you know. But I oughtn’t to be telling you these things. Don’t give me away.”

Now, I was really interested and also upset. It was true that in all the time I spent with her, Joan never spoke Christopher’s name. I asked about Christina, and my question was ignored. “But the twins,” I persisted. “Where are they?” The twins were at boarding school and they were going straight from there to summer camp. They were only nine years old. Other Hollywood children went to boarding schools, too, but when school ended in June, they came home. Even if they were going to camp, they came home for a week or two between school and camp. Not Joan’s children. She didn’t see them; she didn’t talk to them; she just made the arrangements to keep them out of the way.

At least, that’s the way it was while I was there. Yet the curious thing was that she tried to give me the impression that her life was saturated with maternal devotion. She showed me scrapbooks filled with photographs of Joan bathing the children, Joan combing their hair, Joan making milkshakes for them in the kitchen, Joan getting them dressed. The pictures had all been taken by professional photographers, and I began to believe that she had adopted the children for publicity purposes. When they outgrew their usefulness, she discarded them. But she didn’t discard the pretense. She took me to lunch with Judy Garland at the Brown Derby, and all these two women talked about was their children and what good mothers they were. “I always take them to their first day of school,” Judy said. “So do I!” Joan chimed in, her voice soft and sincere, her eyes tender with emotion, “And to Sunday school,” she added. “I always take them to Sunday school.” This was news to me, and I’m sure it would have been to the children.

At Jane Greer’s dinner party, she went on and on about how much she loved her children. Jane’s children were there; living at home and were introduced to the guests. “How I wish mine were home with me!” Joan said fervently. And at dinner at Don the Beachcomber’s, she made Don go upstairs and bring his baby down to our table. “Oh, I love babies!” Joan enthused, insisting on holding this one while explaining, in clear tones easily audible to most of the other restaurant patrons, how much she was reminded of when her children were babies, “Their little feet! Their little hands!” she rhapsodized, (“Well,” I thought, “maybe she loves babies and hates children, the way some people love kittens but can’t stand cats.”)

It was only after I left Joan’s house (at the end of a grueling week of her supervision, the vodka marathon, and the suffocating feeling that I was being gulled by a carefully planned “performance”) that I learned more of the real horror story. I escaped by telling Joan that I had to visit an old Vassar friend who was ill in Altadena. Then I checked in at the Beverly Hills Hotel and saw the friends and contacts to whom I had originally planned to talk, before I let Joan shanghai me. Some of them knew more about the children than others did, but they all agreed that their lot was a hard one. “Joan is a fiend with those poor kids,” one woman told me. “Poor Christopher got the worst of it. He’s run away from home several times because he can’t stand it. A friend of mine was there one day when Joan punished him for something, I forget what, some childish naughtiness. Joan grabbed his arm and held his hand in the fire in the fireplace, while he screamed. My friend was horrified.”

“I think she really hates Christopher,” a film writer told me. “She tied him naked to the foot of a bed and shut him in the room and left him. Someone, I think it was a servant, opened the door by mistake and saw him there, sobbing, but didn’t dare release him. Understandably, when Joan let him out the next day he ran away again. The police brought him back. Joan told them it wasn’t her son and shut the door on the policemen and the boy. They knew it was her son, so they left him there. But she wouldn’t let him in. He had to sleep all night out by the pool. She used to lock him in closets too. She’s really sadistic. You’d think after what she went through when she was a child that she would have compassion for these helpless children who are at her mercy. She calls her treatment of them ‘discipline,’ I think she’s a monster, a glossy monster.”

Some years later I read in the New York Times that Christopher had gotten into trouble on Long Island. As I remember it, he was arrested with some other boys who were firing a gun from a car. Joan refused to have anything to do with him. When he married and brought his bride to meet her at the duplex penthouse Joan and Al Steele had in New York, Joan refused to let them in. He had four children, but Joan never saw them or spoke about them.

Even the “twins,” who, comparatively speaking, were less badly treated, had little contact with her. When Joan moved to New York with Steele, she put Cathy and Cindy, then about ten or eleven, in a hotel with a nanny. Although the Steele apartment had sixteen rooms, not one of the children ever spent a night there.

After Steele died of a heart attack in 1959, Joan made no effort to have a closer relationship with her children. She didn’t see them on birthdays or holidays, not even Christmas. When she herself died last year, she left $2 million, of which her will stated that the twins were to receive a trust hind of $77,500 each. To Christina and Christopher she left nothing. Last winter they petitioned a court to upset the will, on the grounds that when Joan signed it her brain was addled by vodka and the pain of cancer of the stomach, from which she suffered for two years prior to her death. They sought to have the estate divided evenly among the four children. (The case is still pending.)

She spent her last years living as a recluse in her New York apartment, the furniture shrouded in plastic covers, refusing to answer the telephone, seeing only a secretary, a servant, an occasional acquaintance.

Although I never saw her again after I left her house, I received a letter from her in reply to my punctilious bread-and-butter note. She wrote that she had loved having me as a guest. She must have been disappointed, though, that I didn’t write about my visit. I never have, until now. She also sent me a typewritten letter that Christmas and for several years afterward. This was in no way anything to boast about. She may have ignored her family, but she kept a voluminous file of acquaintances, associates, journalists, and fans. Every Christmas she sent 7,000 letters, dictated and typewritten but signed by her in ink. I imagine that they were mostly duplicates.

She spent her last years living as a recluse in her New York apartment, the furniture shrouded in plastic covers, refusing to answer the telephone, seeing only a secretary, a servant, an occasional acquaintance. She occupied her time dictating letters to fans all over the world (those who survived from her once flourishing fan clubs), watching television, and, always, drinking the 100-proof vodka. She never tried to get in touch with her children. To the few people she saw on rare occasions, she referred to her grandchildren as “my nieces and nephews.” That is, if anyone mentioned them or inquired. Usually, she didn’t refer to them at all.

Did she in those last few years ever think back to the plump little freckle-faced girl from Texas and the means by which she climbed inexorably to the top?

She was born March 23,1904, in San Antonio, Texas, and named Lucille LeSueur. Her parents were not married. Her father, Thomas LeSueur, of French descent, left home before Joan was born. She saw him only once in her life, when he came to her movie set in Hollywood in 1934, after reading about her. It was an awkward encounter and she never saw him again. Whether or not she knew, she, never said what he did for a living. She had an older brother, Hal LeSueur, who, at the time I visited her, was working in a garage in Los Angeles. She never mentioned him. (She was not exactly what could be called a family type.)

Her mother, Irish American, started living with a man named Henry Cassin, who may or may not have been in vaudeville. They moved to Oklahoma when Joan, then called Billie Cassin, was about seven. From there they went to Kansas, where Cassin disappeared after trying to seduce Billie. (Did he succeed? There is on no one alive who knows.) They never saw or heard from him again. The mother and the two children lived in the back room of a laundry, where Billie was put to work ironing shirts. Her mother whipped her with a cane if she loitered at work.

She never really had an education. Sent to a Catholic boarding school, supposedly to work her way, she had to wait on tables, wash dishes, clean rooms, make beds. She was the only working student, the other girls snubbed her, and she hated it. She ran away to another school, which was even worse. The headmaster’s wife used to beat her and drag her up and down stairs by her hair. She had no lessons. She escaped and forged a high-school certificate, with which she entered Stephens College, in Missouri, as a working student, but left after three months when it became obvious that she was completely unprepared academically.

She went back to Kansas City, where she worked as a telephone operator and then, for twelve dollars a week, as bundle wrapper and, later, clerk, in two different department stores. She was then in her early teens, already a terrific dancer, with plenty of male friends. A professional named Katherine Emerine saw her dance at some party or gathering and hired her as part of a dance revue she headed. When the revue folded in Springfield, Missouri, Miss Emerine told Billie to look her up in Chicago, if she could get there. Billie arrived in Chicago with two dollars in her purse. Miss Emerine was out of town, but Billie had the name of the agent who had produced the revue in which she had briefly appeared. Through him she got a job for twenty-five dollars a week, dancing in a sleazy Chicago night spot. Later, he sent her to Oklahoma City and then to a club called the Oriole Terrace Café in Detroit, where the manager came to her one night and said, “There’s a big butter-and-egg man outside who wants to meet ‘the little fat girl with the big blue eyes and freckles.’ ”

The “butter-and-egg man” turned out to be J.J. Shubert, the theatrical tycoon, who had brought his musical Innocent Eyes to Detroit for a pre-Broadway tryout. The details of his meeting with Billie are as unavailable as most incidents of her early life, but it is known that he took her with him that Saturday night on the train to New York. Asked about it by a journalist in 1930, she said, “I can’t remember a single thing about that trip to New York.”

She did appear as a chorus girl in Innocent Eyes on Broadway. Nils T. Granlund, the stage manager “took an interest in my work,” as Joan was later to put it somewhat euphemistically. He introduced her to Harry Richman for at private audition, at which Richman the piano while Billie, danced and sang, “When my sugar walks down the street, all the birdies go tweet, tweet, tweet.” The result was a job at the Club Richman. She danced in the Wintergarden’ show six nights and three afternoons a week, and at the Club Richman from midnight until 7 A.M. every night except Monday. Although she weighed 145 pounds When she came to New York, this strenuous routine soon slimmed her down.

Later, she was in the chorus of The Passing Show of 1924, starring the great AI Jolson. She met Harry Rapf, an MGM executive, and J. Robert Rubin, then MGM’s eastern representative and lawyer. Through them she was given a screen test and signed to a six-month trial contract at seventy-five dollars a week. She arrived in Hollywood in 1925. Her first screen appearance was as Norma Shearer’s double in Lady of the Night, played with her back to the camera. She made four other films that year. The first in which her name was listed in the cast (as Lucille LeSueur) was Pretty Ladies, with Norma Shearer, Ann Pennington, and Zasu Pitts. She played a chorus girl.

The studio changed her name to Joan Crawford, a name chosen through a fan-magazine contest. The hit movie that made her a star was Our Dancing Daughters in 1928, in which she played a flaming-youth type of flapper. In all, she made twenty-two silent films and fifty-nine talkies, a total of eighty-one pictures (or eighty-two, if one counts her first appearance, back to camera, as Shearer’s double).

From the beginning, she worked and played hard. She made four films in 1925, three in 1926, and six in 1927. Meanwhile, she spent her nights dancing for fun at places like the Coconut Grove. She won over 100 cups in Charleston and Black Bottom contests. She had beaux galore, of whom among the more notable were Harry Rapf, Paul Bern (advisor to Irving Thalberg, and later to commit suicide the morning after his marriage to Jean Harlow), and Mike Cudahy, of the Chicago meat-packing family, who drank too much and whose mother haughtily disapproved of Joan. And, of course, there was always the notorious Hollywood ogre Louis B. Mayer, the head of MGM, without whose favor no woman, except possibly Garbo (and who really knows about her?) ever achieved big stardom. “I always called him Mr. Mayer,” Joan told me primly. And maybe she did, no matter what went on between them.

Her one close friend, a platonic one, was Billy Haines, a leading male juvenile until Mayer found out he was a homosexual and fired him. Haines became a successful interior decorator. He always called Joan “Cranberry,” because that was the color of her hair when she first went to Hollywood. He remained her friend and confidant until he died. She never had close women friends.

Her first marriage was in 1929 to Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. He was only nineteen. She was twenty-five, although she gave her age as twenty-one. Her stepmother, Mary Pickford, disliked Joan and was against the marriage. Whenever Doug took his bride to Pickfair, his father’s famous mansion, Joan was snubbed by Mary, who never spoke to her if she could avoid it. (This was Joan’s version, not Doug’s.) Their marriage didn’t last. They were separated in 1933 and divorced later.

Her second husband, Franchot Tone, was a Cornell University graduate, the son of a rich industrialist, and a serious actor. He had been a member of the famous Group Theater in New York in the thirties and had also appeared on the stage opposite Katharine Cornell and in Theater Guild plays.

No marriage with Joan could last, because each husband inevitably became “Joan Crawford’s husband.” It was the same with all her lovers. The fierce ambition and lightning-bolt energy that had fired her upward climb prevented her from ever sustaining a normal human relationship.

Did she realize that other stars had come out of backgrounds as poverty-stricken and as sordid as her own, yet had maintained a humanity and a warmth she totally lacked? Probably not. For so many years, she had acted out her own rigorously grandiose idea of herself. Her only true dedication was to Joan Crawford the Star. She was a self-manufactured glamour symbol, but a woman with no heart.

[Photo Credit: George Hurrell via LACMA; with Douglas Fairbanks, Jr by Edward Steichen via The Art Institute of Chicago; Yousuf Karsh via The Art Institute of Chicago; and another one of Joan with Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. by Edward Steichen via The Art Institute of Chicago]