Has any writer since Boswell possessed a shrewder sense of careermanship than Truman Capote? Gore Vidal expertly packages his arch, marcelled aphorisms for television consumption, Norman Mailer at his most combative has an Elizabethan bravado (though Mailer of late seems sullenly muted), but at fashioning a persona and hustling one’s work, Capote is peerless. For almost 30 years, his image has been shaped vividly in the public consciousness: from the spookily precocious man-child on the jacket of Other Voices, Other Rooms to the lordly host of that celebrity-celestial party of 1966; from the video Capote, giggling grisly stories on the Tonight Show to the movie Capote, swollen and tremulous in Murder by Death. Indeed, his signature mannerism—the way he habitually wipes his eyes, his flicking saurian tongue, the mewing, skinned-cat voice—have been appropriated by comedians to upholster shabby “fag” jokes.

But commercial success can armor one against such whizzing arrows. In Cold Blood (of which the cover of my paperback shouts, “Over 3,500,000 sold!”) was promoted with the tactical genius of Robert E. Lee—one critic hailed the book three years before it was published—and Capote has publicized Answers Prayers for a full decade, reportedly receiving offers of $1,500,000 for paperback rights, a toweringly handsome sum for a work not yet completed. Considering the scandal that Answered Prayers has kindled, perhaps now is an appropriate lull in which to consider it in its sections as a work of art, gossip, and autobiography. This, then, is a provisional report and as such objections can be raised against it. All objections overruled.

Answered Prayers which Truman Capote has been preparing since 1958, and which he once promised to complete by 1969, has thus far been published in Esquire in three installments: “Mojave” (June 1975), “La Cote Basque, 1965” (November 1975), and “Unspoiled Monsters” (May 1976). Despite Esquire’s pompous black-limousine presentation of “Mojave” (the editions started the story on the front cover), I thought it a modest but genuine accomplishment. Even with sententious dialogue—“We all, sometimes, leave each other out there under the skies. And he never understand why”—and a banal central metaphor (e.g., the Mojave Desert as the ‘nadir’ of pitilessness), the story managed to suggest wisps of dread drifting through the sumptuous Beekman Place lair of the protagonists. As the husband tells the story of an old blind man abandoned by his cheating wife in the desert, I heard echos—of Gide, of Paul Bowles—and at the conclusion of this chronicle of estrangement among the rich, one thought of John O’Hara at his terse best.

Since my taste for Capote has always written most at a small scale—as in the exquisite travel sketches of “Local Color,” the novellas of The Grass Harp and Breakfast at Tiffany’s—the lapidary delicacy of “Mojave” was pleasing. Pleasing also was the near absence of the John-Boyish nostalgia-clogged sentimentality which constitutes crowd-pleasers like “The Thanksgiving Visitor” and “A Christmas Memory,” and muddles even the best passage of Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

Yet one scene was troubling. Describing how the protagonist Sarah makes love to her roly-poly psychiatrist (if “Mojave” were a movie, the doctor would be played by Jack Weston), Capote writes: “To judge from appearances, orgasms were agonizing events in the life of Ezra Bentsen he grimaced, he ground his dentures, he whimpered like a frightened mutt … it means soon his lathered carcass would roll off her…” Of course, compared to Updike and Roth and Mailer, Capote’s contribution to the literature of sex has been nugatory, and in journalism and fiction he has always been more comfortable with tomboyish heroines like Holly Golightly. Still, the gritty vividity here—grinding dentures, doggy whimpers—was a repulsive surprise. It struck one as not a Swiftian fury against the flesh, but as a sneery scorn of men and women together.

Mild it was compared to what was to come.

Stanley Kauffmann noted the cinematic elements of In Cold Blood—close ups of the Clutter family, panning shots of the Kansas landscape—and in “La Cote Basque, 1965,” the camera moves with Ophulsian fluidity from table to table, contrasting the opulence of glistening crystal glasses and extravagant dishes with the bitchy, pissy venality of the conversation. Certainly, Capote has an assassin’s gift for garroting his subjects with their own quotes: In “The Muses are Heard,” he made easy sport of harmless philistines like Leonard Lyons and Mrs. Ira Gershwin, and in “The Duke in His Domain,” the victim was Marlon Brando. The Brando article, though smoothly, handsomely readable, is disingenuously done, not only because Capote’s I-am-a-camera technique masks his own role in the action, but because under examination it is his values which are twisted. As Pauline Kael notes, “Capote, in his supersophistication, kept using the most commonplace, middlebrow evidence and arguments against [Brando] … [It] is he in this interview, not Brando, who equates money and success with real importance.” Years later, in a self-interview published in The Dogs Bark, Capote again ridicules Brando, but a few sentences later is this exchange:

Q: What is the most hopeful word in any language?

A: Love.

Q: And the most dangerous?

A: Love.

This ping-ponging whimsey is dopier than any of Brando’s gas.

In “La Cote Basque, 1965,” Capote’s sense of superiority seems equally precarious. Gloria Vanderbilt Cooper and Mrs. Walter Matthau are chattering ninnies here (the much-married GVC being so dim she doesn’t even recognize her first husband when introduced), Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and sister Lee make their obligatory entrance, the moist underbelly of the Beautiful-People realm is gleefully charted (there is bestiality, bloodied sheets, and murder), and what comes through is that the pulpiest in the room is Capote’s. It is Capote who turns La Cote Basque into an abattoir of hatefulness; through his ventriloquial observers, Lady Ina Coolbirth and P.B. Jones, Capote scans the room with a mean white heat, leaving the air thick with the smell of roses and smegma and flesh on the fry.

There is, for example, the Jewish business mogul Polaroided for posterity “pumping a dark fat mouth-watering dick”; there is the governor’s wife of whom it is said, “Kissing her … was like playing post office with a dead and rotting whale: she really did need a dentist.” The faint whiff of death that rises from a cavity is present in these pages, but Capote cheats—just when the death smells give some intimation of the voluptuous cannibalism of the Beautiful-People, of the rot beneath the surface of their overpampered lives, he goes cute and soft, dropping names and snotty apercus as if he were writing not a fiction but a high-society Baedeker for squares.

I remember seeing Capote on a talk show once, regaling the audience with an anecdote about a woman who never washed her hair, merely sprayed and sprayed it, then was discovered dead, stung to death … an autopsy revealed that in her bouffant nested a family of tarantulas. Though Capote writes with a nasty brilliance—his style has not withered with the years—finally that’s the effect of “La Cote Basque, 1965”: that the stories of Life-at-the-Top scumminess are there to provide a glimpse into the fissures of a decaying society (even though the last sentence strikes a twilight-of-the-West note), or to locate the cancers which leave the BPs in a glossy Avedon-portrait desiccation but exist quite simply to provide live-wire jolts of gossipy delight. In the folds of Truman Capote’s mind is where the tarantulas are nesting.

After the firestorm controversy cause by “La Cote Basque, 1965,” a controversy splashed with gasoline by the suicide of a woman who was portrayed in the story as a successful husband-killer, Esquire, which has suffered dips in readership and advertising in recent years, went for broke with the next installment, putting Capote on the cover as a blade-caressing killer. Helpful of them. For it serves to remind us that so much of Capote’s popularity rests upon his salience as a public figure. His career began in 1948 with the publication of Other Voices, Other Rooms, a novel which linked his reputations to writers like Harper Lee (a close friend: he put her in Other Voices, Other Rooms, she put him in To Kill a Mockingbird), Caron McCullers (another friend, until they had a falling-out), and Tennessee Williams. Compared to say, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, Other Voices hasn’t held up very well—it’s a mossy, brackish Garlic soup—but Capote had the smarts to spruce up an image, saying, “it’s so important to build a career … Be seen in the right publications. Mademoiselle, Vogue.”

It paid off. Even In Cold Blood, which banishes the “I” and maintains a fake Flaubertian distance, our response is so hugely influences by the knowledge that it is not William Bradford Huie or John Hersey doing dogged journalistic duties, but the plumed prince of Vogue. Capote have so many interviews on the investigative intricacies of assembling In Cold Blood that it became not only a story of murder in the American heartland, but a trumpet-and-drumroll personal achievement as well, and, indeed, an interview published in Life afterwards was called, “How the ‘Smart Rascal’ Brought It Off.” Reading the book now, what Capote brought off isn’t so clear, for though it’s a work of extraordinary, even courageous diligence, it only skirts the edge of greatness. In Cold Blood is an absorbing narrative and is astonishingly attentive to the nuances of Kansas life, but it’s overcrammed with peripheral details, perfumed with pretty-pretty prose.

As alliterative as what I’ve just written, and crippled by a moral schema which is cracked at the spine. The central tragedy of the book is not the slaughter of the Clutters but the blighted, battered life of Perry Smith; and it’s clear that the book’s title is meant to express a moral symmetry—that the execution of Smith by the State is as In Cold Blood as the carnage at the Clutter farm. It’s a symmetry which I reject, but this is not the place to argue about capital punishment. What’s disturbing is not that Capote brought Perry Smith to vivid life (that’s his duty as an artists), or that he identified with Smith (who hasn’t identified with Raskolnikov?), but that the identification was so passionate. Harper Lee said in an interview that “every time Truman looked at Perry he saw his own childhood,” and when Smith was executed, Capote sobbed uncontrollably for three days. In his will, Perry Smith left Capote all his earthly possessions.

Now of course, the cruelties of Answered Prayers are not remotely compared to the killing of In Cold Blood, but Capotes forces the associations by posing as a Galleria Jack the Ripper. After all, the most famous quote, the most famous moment, in In Cold Blood is when Smith in his confession says: “I didn’t want to harm the man. I thought he was a very nice gentleman. Soft-spoken. I thought so right up to the moment I cut his throat.” Like Hemingway, who played Papa the white-bearded Fisher-King for so long that our perception of his work is forever blurred, Capote’s black-cape role-playing compels us to see all his work in the shimmer of a poised stiletto.

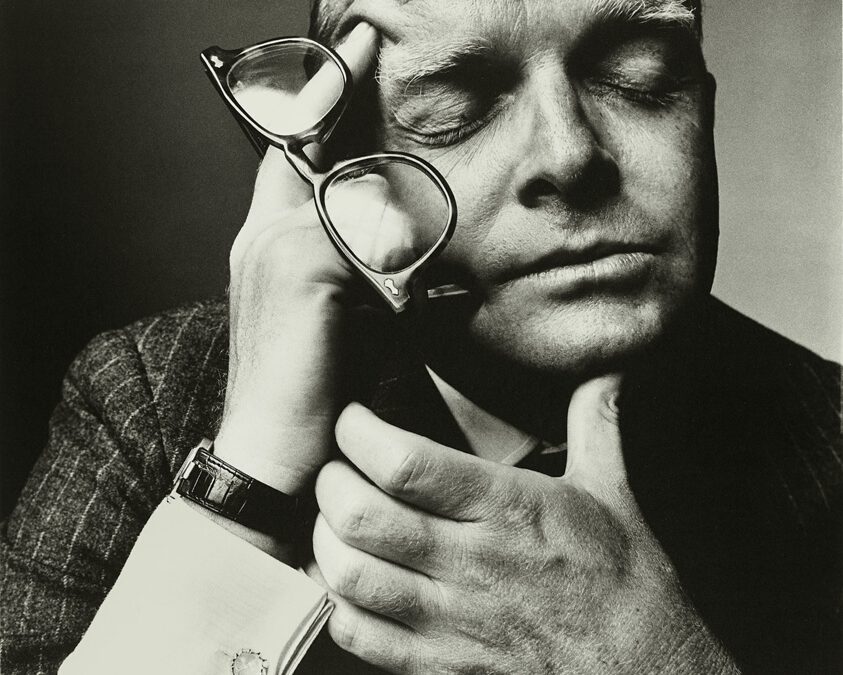

“Unspoiled Monsters,” the story adorned by this cover photo, is a picturesque onward-and-upward-with-the-arts adventure in which the autobiographical hero, P.B. Jones, moves through cultural status-sphere equipped with wit, cunning, a cock which he wields like a dildo (which is to say: with cold professional flair), a pair of nostrils sensitive to every aromatic hue of puke and perfume. Despite the Smottettish skids—“I remember slipping in a mess of champagne vomit and dislocating my neck”—and the spiky digs at celebrities (Ned Rorem is “a queer Quaker,” Sartre is “Wall-eyed,” Arthur Koestler is a brute, Tennessee Williams appears as a dreamy derelict, adrift in an excremental seas), yes, despite all the flying shrapnel of Capote’s contempt, the narrative is sentimental at the core. P.B. Jones is, like Capote, a stray, a young man from the provinces, a changeling; Jones says of himself, “I am a whore and always have been.” Never is an artist more self-enhancingly self-deprecating than when fashioning himself as a whore, particularly since the scheme of “Unspoiled Monsters,” all artists are whores, even Samuel Beckett, who has for his mistress a “rich and worldly Jewess.” In a meretricious world where everyone is on the make Jones’s candor is intended to make him a whore of caliber.

In this installment, we have a fuller introduction to the book’s cyclonic force, Kate McCloud, who appears to be a romping tomboy ala Holly Golightly, but the most important development is that the novelistic strategy of Answered Prayers is unveiled. The heroine of “Mojave” is revealed as based upon McCloud’s best friend; the masseur from that story turns up rooming at the Y in a room next to Jones’s; there is a further, if thinner, strand: the killers of In Cold Blood had not only driven through Mojave but also, in a different leg of the journey, picked up two hitchhikers, one of them an enfeebled old man. And incidents from Capote’s memoirs in The Dogs Bark—a tribute to Jane Bowles, a meeting with Colette—are interwoven with the fictional exploits of Jones, who himself is writing a book called Answered Prayers. So: in Answered Prayers, Truman Capote is writing a novel about a writer who is writing a novel called Answered Prayers.

This Chinese-box technique is, of course, not Capote’s invention. In recent novels, it has been employed by Philip Roth in My Life as a Man, Gore Vidal in Two Sisters, Norman Mailer (Charles Eitel of The Deer Park became Frank Idell of The Man Who Studied Yoga) and by Nabokov in his masterpiece, Pale Fire. At issue here is not only the relationship of an artist to his work, and of the work to the artist’s reputation, but the very elusive and allotropic nature of reality itself, which, according to Lionel Trilling is the essential quest of the novel.

Perhaps Capote can rise to greatness in such a quixotic quest but thus far he’s charted his course in a patronizing, connect-the-dots manner. After some musings about Proud, Jones asks, “That’s the question: is truth an illusion, or is illusion truth, or are they essentially the same?” Chirp, chirp. Yet Capote-Jones plays with a paradox which is more illuminating: “The female impersonator is in fact a man (truth), until he recreates himself as a woman (illusion)—and of the two, the illusion is the truer.”

It’s illuminating not for its intellectual worth—which is pretty vaporous, actually—but because for me it explains what Answered Prayers is about; it’s not merely mischief and revenge, but an extended exercise in the travesties of Camp. In its celebration of the androgynous (of which, more later), it’s numerous breathy references to Vogue appurtenances (Vedrura cuff links, Baccarat crystal paperweights), it’s ’70s dandyism (Sontag: “The connoisseur of Camp sniffs the stink and prides himself on his strong nerves”), Capote is creating a work of Camp at its most contrived and self-aware, a fiction so ferocious in its desire to be bitch-witty that it is pantingly overwrought.

And worse. The loathsome side of Camp’s homosexual sensibility is its ironic adoration of Woman, contemptuousness of women. In Answered Prayers so far, the only women treated chivalrously are lesbians. As for the others, well, one is described masturbating while “recalling … a pasta-bellied, whale-whanged wop picked up in Palermo and hog-fucked a hot Sicilian infinity ago?” Another is a “white-trash slut” photographed “being screwed front and back by a couple of jockeys in Sarasota,” and of Kate McCloud it is said if she “had as many pricks sticking out of her as she’s had stuck in her, she’d look like a porcupine.” Nearly all of the women are seen as spoiled, hungry gashes, and even is misogyny at is most maniacal has comic possibilities—as in the great French film Going Places—Capote’s language is so flamboyantly filthy, so baroque in its effects, that laughter is not allowed air to breathe. Something similar happened when Mailer attempted to create a scatological symphony in Why Are We In Vietnam? as the obscenities came relentlessly crashing down on the page, it was like trying to listen to Wagner with a hangover.

Musically, Capote is close to Mendelssohn, but still. Though it is very dangerous to equate the values of a writer with his creations—too many have confused Portnoy with Roth, “Henry Miller” with Henry Miller—one can’t help but wonder why Capote is working off all this rancor. Is he telling the patronesses of the Vogue world what he really thinks of them, or does he think all human affections end in dung, or what? The strained campiness in the very marrow of the prose reduces the deaths and abandonments of Answered Prayers to ghoulish jokes—one character dies on the toilet, another is carved up by a Puerto Rican hustler, his eyeballs left dangling—and if the grotesquerie often rises (lowers?) to an amusing Terry Southern level, well, it’s not enough. The drilling message of Answered Prayers as it unfolds is that the very, very rich are different from the rest of us because they care more for the “chilled fire” of Roederer’s Cristal and the “golden rivers of egg yolk” in souffle Furstenberg than they do about the wrecked lives around them; that was the message of The Magic Christian, too, and the Camp bluster there had a more boisterous spirit. Kate McCloud is the key, for if Capote can create a heroine of dimension, an Emma (Austen’s, not Flaubert’s) who careens through society full of fire and narcissism and amphetamine, then Answered Prayers will be truly formidable, compelling phenomenon. But as it stands: gossip dines with Camp and sups on the flesh of the famous.

[Photo Credit: Irving Penn via The Art Institute of Chicago]