Stockton, Calif.—The Memorial Civic Auditorium, located not far from the central ganglia of this crumby hick town, is old, cavernous, sweltering hot, and overripe with the stink of vintage sweat and piss. The litter-strewn floors are coated sticky with spittle and worse. The gallery semicircling the glaringly lit prizefight ring in the middle of the hall is packed with cretins and worse—San Joaquin Valley fruit bums, rheumy-eyed winos, Right Guard dropouts, mean-faced Pachuca-chicks swilling Oly from cans.

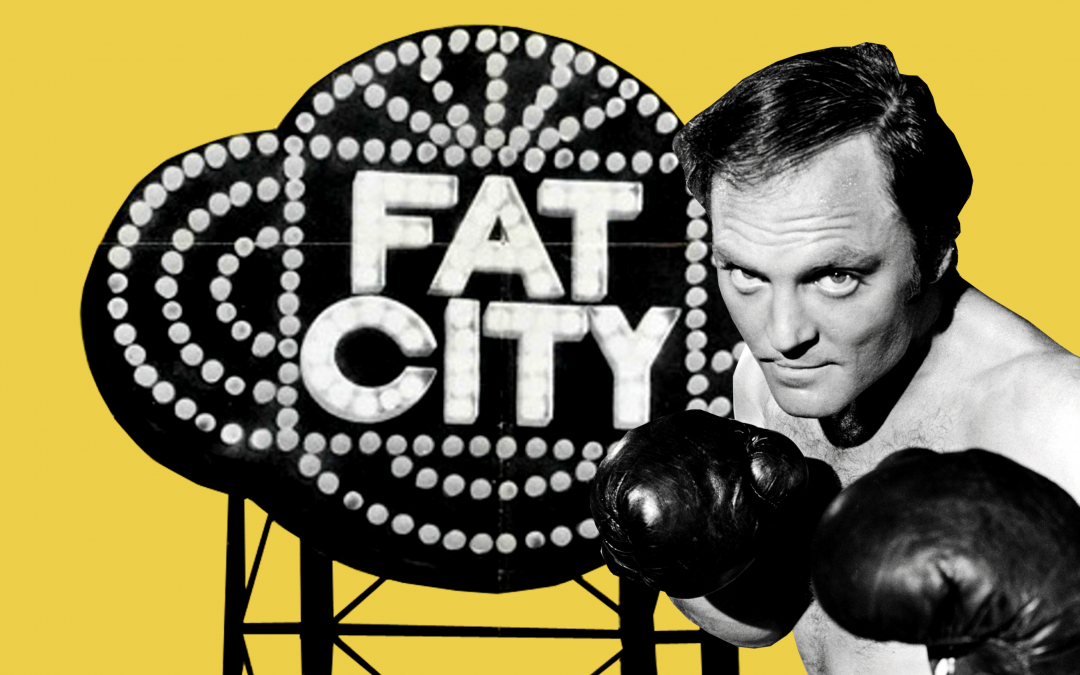

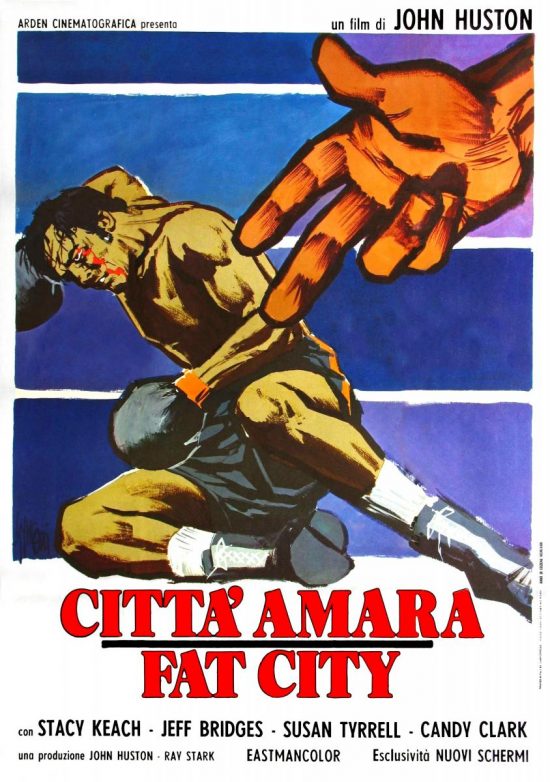

Occasionally, as the furious action in the ring prompts them, this mob of six-hundred-odd tank-town lames roars its bloodthirsty approval. And the action going on in the ring is … wait a second here … just what in the name of Christ’s sweet body is a nice, classically trained actor like Stacy Keach doing in a creep joint like this?

Making a movie called Fat City, of course—and at this precise instant, that means he’s getting the living firk wailed out of him by one Sixto Rodriguez, an honest-to-god light heavy bruiser who once clobbered Bobo Olson to a viscous pulp and battled both Von Clay and Piro del Pappa to bruising draws.

It’s all in the script, understand, but try explaining that to Judy Collins, Keach’s special lady. Out of camera range, she’s standing with director John Huston and the film’s producer, Ray Stark, and she winces fretfully every time she hears leather slam into meat. Huston, a big, loose-limbed man in a tan gabardine safari outfit and penny loafers, lights a panatela and pats her on the shoulder in commiseration before she wanders away, looking stricken. “It’s only a movie, my dear,” he calls after her softly. Nearby, a bored grip man grips a fog gun which emits an acrid shmaze resembling tobacco smoke; Leonard Gardner, the author of Fat City in both novel and film version, stumbles through the nose-stinging vapor, looking tiny, frail, and maybe lost.

While cinematographer Conrad Hall (Cool Hand Luke, In Cold Blood) calls a sotto voce consultation with Huston and Stark, Keach and Rodriguez continue to spar. “Christ,” an electrician mutters, “those guys been at that shit seven hours now. You’d think they’d take a load off.” Stark, a slight man wearing a knit shirt and an expensive imitation of Levis, shakes his head violently at Hall: “No, no, no, no, no,” he says, raking an exasperated hand through his longish, ginger-colored hair.

The action resumes. Up in the squared circle, Rodriguez quickly knocks Keach to his hands and knees. “Oof,” Keach says, looking as if he means it. “Kill the bum!” some demented honky-tonk woman cries from the balcony. Keach wobbles to his feet, snakes out a weak feint, and this time Rodriguez nails him but good. Back down to the canvas on his hands and knees, hair matted with sweat, nose and eyes streaming, Keach says over and over, “Ooof, ooof, ooof.”

That evening, at the suburban ranch-style house he’s sharing with Judy Collins during Fat City’s location shooting, Keach proves to be much more articulate. Wearing a tie-dyed jean jacket and Army surplus pants with a U.S. flag stitched on the hip pocket, he introduces some visitors to his friend and aide-de-camp, Billy Comstock, explains that Judy has driven into San Francisco for a recording session, and leads the way to a big, pleasant sitting room. “What can I offer you?” he asks with an expansive gesture of his balloon-swollen hands. “Wine, beer, grass?”

While Comstock adjusts the volume downward on a James Taylor album and fetches the refreshments, Keach sprawls in an overstuffed chair, gingerly caressing one raw hand with the other.

“What’s really important to me, is intimate relationships with people, trying to open up and be less defensive to people, more genuinely interested in the experiences you’re sharing with them.”

“Yeah, Judy’s my old lady,” he says in a musing tone, “that’s no secret. We’re not married, if that’s what you mean. De facto, yes, legally, no. We’ve been together, lessee, I guess over two years now. Even my family pretty much accepts the situation by now, although that’s not to say there haven’t been some pretty hairy moments….

“Judy makes me a happy man—it’s that simple. We share a lot of things, and we’re not intimidated by one another as we were at the beginning. We work together and we talk everything out, and we try to be as open and honest with each other as we possibly can. So we’ve talked about marriage from time to time, and tried to figure out what use it is as an Institution outside of a legal means of protecting children. We’re just cooling it for a while, waiting to see what happens, trying to psych out what’s right. See, I was married once, quite unhappily, as it turned out. I was much too young for it—twenty-two, twenty-three.

“What’s really important to me, and becoming more important all the time, is intimate relationships with people, trying to open up and be less defensive to people, more genuinely interested in the experiences you’re sharing with them. You know, without bullshitting, or some kind of ulterior motive. I think people, a lot of people, are trying hard to get into a new thing, trying to achieve a kind of breakthrough to an achievement of personal dreams and goals without impinging or presuming on others. I’ve just been reading The Greening of America, and Reich touches on what I mean, to an extent. His book is important, I think, because it articulates a point of view that’s been in need of being put together for a long time—not so much for the people it describes as for the larger middle-class audience that doesn’t know, doesn’t grasp what’s going on….

“I think as I come to understand more of myself and the people around me, my life gets … simpler. Judy and I have a house in Connecticut, and when I’m not working, I like to just loaf around there, hang out, you know, read, listen to music, get stoned … L.A. totally turns me off. Every time I have to go there, I get traumatized—I actually start getting catatonic. I grew up there, you know, and then went to U.C.-Berkeley and after that the Yale Drama School. As a kid, I spent most of the summers down in Taft, Texas, with my grandparents. Those summers saved me, in a way. There was a freedom and a reality in Texas that I never knew in L.A. I guess it was always that vacuousness, you know—the need to reach out and touch something real, but there was nothing real there, even less that’s real there now. I don’t know—the kids, maybe. But even the kids don’t seem real down there. The Los Angeles-ization of the planet.”

Keach scowls morosely and takes a deep swallow of wine. Outside, a backfiring hot rod barrels down the otherwise still street with a sound like a fusillade of gun shots.

“The Los Angeles-ization of the planet,” he repeats, looking glum and pained and slumping further down in the chair.

“See, like a lot of people, I don’t like most things that’re going on in America nowadays. The injustices that’ve gone down and are still going down. I mean, I hate Nixon—at least the things he stands for. But when I stop and reason it out, I realize those kind of negative vibrations aren’t ultimately doing me any good. My politics are … liberal, I guess. I don’t dig violence in any form, whether it’s throwing rocks or offing the cops. It sounds like a cliché from in front, but I feel the only way the people are going to get together at this point . . . I mean, just in my own experience, I know I don’t have to look too far anymore to find somebody who shares my views and interests. It sure as hell wasn’t that way five, six years ago.”

Keach leans forward intently, frowning in concentration. “So where does that leave somebody like me? With the people I love and my work, as far as I can figure it. I’ve been lucky in both respects. The films I’ve made so far—The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, End of the Road, The Traveling Executioner, Doc—haven’t been uniformly successful, but they were all interesting and offbeat, and each of them was a challenge for me. In a way, Fat City is my favorite. Part of it has to do with working with John Huston and Connie Hall. Huston is incredible, man—larger than life. He’s a kind, brilliant guy, and I mean, he sees everything. He knows exactly what the finished film is going to look like. And Hall—goddamn, what a talent! He reacts to the emotion of a scene with light, and the results are fantastic. He’s better than any two other cameramen I’ve ever heard of.”

Keach tosses off the rest of his wine and excuses himself; he’s got a 5 A.M. makeup call. On the drive back to the Holiday Inn, where the film troupe is quartered, one of the visitors asks Billy Comstock what he principally does, working for Keach. Comstock flashes a lopsided grin. “Drive,” he says.

Round about midnight, Leonard Gardner weaves to a corner table in the hotel’s cocktail lounge, looking definitely lost by now. Stirring his drink with a doleful finger, he launches into a morose recitative to his drinking companion about the recent split-up of his long-standing love affair with a lady novelist in San Francisco. “Well, I lost her, goddamn it,” he concludes with a bitter grimace, “and now I’m back down here in Fat City choppin’ weeds.” What he’s said is a paraphrase of a line in his book, which is more about losers than it is about boxers, and an affecting one.

“Am I mad?” he growls rhetorically. “You goddamn right I’m mad, man. All this bullshit Hollywood stuff is getting to me. I want to strangle somebody. How about a self-destruct movie? Why not? I’d like to bomb somebody, but I’d need an accomplice. Somebody who can run slower than I can.”

Early the next morning, Keach and Sixto Rodriguez are going to Fist City again in the auditorium ring, the fog gun man is busily squirting puffs of smoke like benign CS gas up toward the plug-ugly extras in the gallery, and shooting handhold. Perched on a high canvas stool with his name lettered on the back, Huston sips from a paper container of coffee and confirms the scuttlebutt on the set that there’ll have to be some retakes on the picture. “Not all that much, though. Some of the stuff’s too dark for drive-in showings, is all. I fucked up on a few things.”

“Agee was, I think, essentially a poet. He was perhaps the finest writer I’ve ever worked with.”

Laughing in a booming basso, he fishes through the pockets of his bush jacket for a panatela. “I haven’t made a picture in America since The Misfits, you see,” he says, clipping off the end of the cigar, “and that was eleven years ago. Oh, no, the fact of my having taken out Irish citizenship doesn’t mean I’m in exile from America. Far from it. I follow events here very closely, and for the first time in a long time, I think I see some light at the end of the tunnel. The country’s response, for instance, to the Pentagon Papers. Older people are belatedly but surely waking up to the reality the young have been aware of for years.

“The Misfits, yes … Gable was in it, of course, Monroe, Montgomery Clift, all gone now, as many of my close colleagues are gone … James Agee, Bogart. Agee was, I think, essentially a poet. He was perhaps the finest writer I’ve ever worked with. He had great sensitivity, and he was one of those rare people who was completely aware of the complexity of life around him. He was the most modest and dearest of men, and very strong, too, within himself.

“Bogart was another type of person entirely. I was personally very fond of him. We did some six or seven pictures together, and over the years a friendship developed between us that is uncommon in this business. Bogart loved a good time, loved to celebrate his successes. He had a certain worldliness that I imagine would’ve made him laugh at the present ‘Bogart cult.’

“Monroe, umm. I must confess I didn’t recognize her potentialities when I first worked with her. I only did two films with her—her first, and, as it turned out, her last. I had a sense during the filming of The Misfits—and I think all of us did—that she was headed for the rocks and disaster.

“Monty Clift was, in a sense, the male counterpart of Marilyn in my life. Again, I did only two films with him—The Misfits and Freud. In his last years, he was far from well, either physically or emotionally. Monty was on his last legs, too, during the making of Freud. Among an assortment of ailments, he was going blind from cataracts. A pathetic figure.

“By way of contrast, it’s a joy to work with someone as strong and stable as Keach.

“My plans after the filming? Vague. Inchoate. Except to go back to Ireland and get on a horse’s back.”

Ray Stark strolls by to tell Huston good-bye before leaving for New York. He pats his briefcase significantly and winks: “Well, it’s time to take the money and run, John baby. The picture looks good so I might as well finance it myself. Take good care of the store.” Nearby, a grip bites into a breakfast roll and winces: “Jeez, this tastes like a Frisbee with grease on it.”

Up in the ring, Rodriguez challenges Keach with mock ferocity: “Hey, gringo!” Keach assumes an awkward crouch-and-advance stance a little like the young Gene Fulmer. After the two trade a few tentative feints, some intangible tension that’s built up between them all morning abruptly blows, and there’s a moment of joyous, anarchic release. Howling with glee, they spontaneously fall into each other’s arms and begin waltzing. Waltzing in Fat City. The goons in the gallery eat it alive as Keach and Rodriguez swing-and-sway around the ring.

But at a signal from Conrad Hall, the two retire to their respective corners, and when the bell clangs, rush toward each other, swinging savagely. Head down, chin in, Keach furiously windmills Rodriguez’s midsection until Rodriguez gets a clear shot at his temple. Then, stunned and glassy-eyed, Keach goes down to the canvas on his hands and knees, hair matted with sweat, nose and eyes streaming, saying over and over, “Ooof, ooof, ooof.”

[Illustration: Elena Scotti/GMG]