I have been trading war stories with other Vietnam veterans for two decades. I almost never believe the stories they tell me, any more than you should believe mine. I don’t mean these stories aren’t true, just that they probably didn’t happen quite the way they’re told. For example, if a Vietnam veteran tells you he returned home to America and was spit on by hippies when he got off the plane, that’s almost certainly a lie; there weren’t any hippies at the air-force bases we returned to. But it’s a good story, because it goes to the heart of how we felt coming home to a country that hated the sight of us.

If he tells you he shot women and children, that’s probably a lie; it happened, but very rarely, and it made such a powerful impression precisely because it was so out of the ordinary. But it’s a good story, because it goes to the heart of the confusion and guilt we feel from fighting a war where ten-year-olds could kill you, where it was almost impossible to tell friend from foe and easy to give up trying.

If the veteran tells you he can’t talk about Vietnam, that’s probably true, perhaps because some part of him was touched beyond words: by love, joy, shame, or horror—and those are the stories still to be told.

The real Vietnam War ended in 1975. Everything about it since then has been a war story—which means it’s been made up, wrested from a stubborn memory, shaped by imagination, and transformed by the stories already told. The war shaped American culture; since it ended, American culture has shaped the war. The men and women who fought in Vietnam are made up by others, the way the real cowboys and outlaws of the old West were made up by Ned Buntline, Tom Mix, and John Ford. The books, television shows, and movies don’t just tell us about Vietnam; they are Vietnam.

But at the very core of the myth, the tiny, powerful seed, are our own myths, our war stories. War stories are the oldest stories, the same ones over and over: the loss of innocence, the conquering of fear, the hopelessness of death, the occasional victory of love, all against a backdrop of stunning, indifferent nature. War stories are the rag and bone shop of the heart, the relics adorning the altar of the past, the incantations that bring the dead back to life. In Tim O’Brien’s powerful new work of fiction, The Things They Carried, there’s a pile of body parts with a poster on top that reads: Assemble Your Own Gook!! Free Sample Kit!! We were in Vietnam: here are our guts and the pieces of ourselves we left there. They don’t belong to us anymore. So assemble your own movie or book; free sample kit.

I. The Art of War

Vietnam exists in the imagination now, a geography of intense images increasingly disconnected from the real place. The war we all wanted to forget has become an enduring setting for literature, theater, television, and film, a mythical place like Camelot or the Holy Land, the galaxies of Star Wars, or the urban precinct house: Each Vietnam movie was supposedly the last, the final light at the end of a long tunnel. But instead of subsiding, the flood of movies and books about Vietnam has increased in the past few years: the war in the imagination is even harder to end than the real war.

The war won’t end precisely because it was so painful and so senseless: because Vietnam, like the American West, is such a rich, confusing, unmanageable canvas. America found itself in the Western and lost itself in Vietnam—a war we didn’t understand, didn’t want, and didn’t win, a lock-and-load, rock-and-roll war, good and evil, ennobling and degrading, all at once. The choices weren’t clear, the issues were confusing, the music was turned up full volume. Vietnam was a government-sponsored Altamont, the dark side of the sixties. Its stories haunt the memory; they stimulate the imagination to invent new stories, new truths.

There has been no end of excellent books about the war, from Dispatches to The 13th Valley, most absorbed with the first task of art—getting it right. Perhaps because television had brought the real war so intensely into our homes, the first films either avoided the war itself entirely (Hal Ashby’s Coming Home) or used it as a setting for a mythic vision (Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter). Then came Roland Joffe’s The Killing Fields, about Cambodia; then the cartoon of Rambo: First Blood Part II in 1985, followed in 1986 by its realistic opposite, Oliver Stone’s Platoon, and the floodgates opened. Major directors such as Stanley Kubrick (Full Metal Jacket), Brian De Palma (Casualties of War), and Barry Levinson (Good Morning, Vietnam) made Vietnam a standard in the Hollywood repertoire. Their films were joined by a stream of lesser features, television movies, and two network series, China Beach and Tour of Duty.

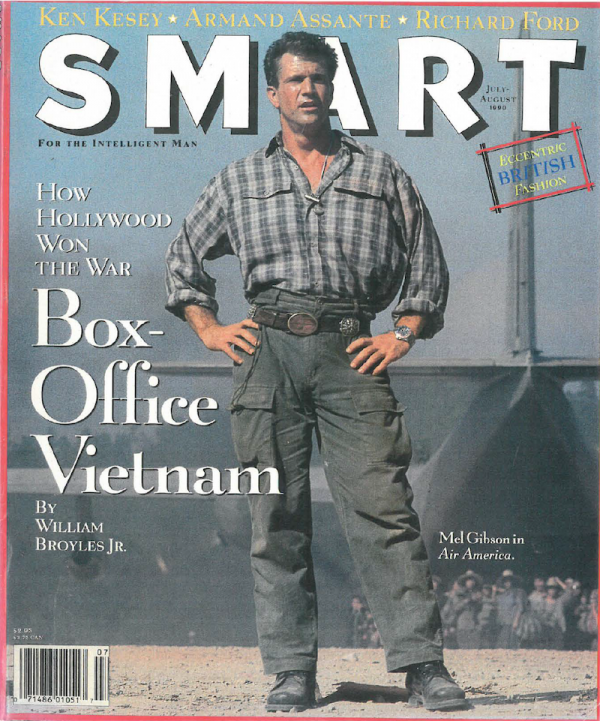

This winter saw Oliver Stone’s second Vietnam film Born on the Fourth of July, and the summer will bring movies set in the air war: John Milius’s Flight of the Intruder, about the navy pilots fighting the deadly battles over North Vietnam; and Air America, with Mel Gibson and Robert Downey Jr. as civilian pilots who flew in the secret war next door to Vietnam in Laos. Gibson plays a war-weary pilot trying to build a black-market ticket out for himself and his Laotian family; Downey is in for the excitement and the challenge—the war is better than flying traffic helicopters in Los Angeles.

This film is not without political overtones, but it seems more inspired by the hard-boiled, gritty charm of movies like Howard Hawks’s Only Angels Have Wings, where Cary Grant leads a band of rough-and-tumble, yet lovable, pilots and Jean Arthur is the woman who warms his combat-hardened heart. Air America uses the war in Southeast Asia the way the Indiana Jones movies use archaeology. Next year will even see a Broadway musical called Miss Saigon, a Madame Butterfly tale that is yet another example of how protean the war has become. Vietnam—there’s something there for everyone. The war is a device, a convenience, a setting in which ordinary people can be stripped to the basics and subjected to the terrible pressures of life and death; it is a mirror in which we see what we wish to see, and, if we look closely, ourselves.

Once upon a time… There was a real war where the blood didn’t wash off. The wounded didn’t get up and walk. The paralyzed never made love again. The dead stayed dead.

But the war isn’t a hoary, mythic chestnut, not yet. Some of the best movies have been the most realistic. The moral and political passions that the war engendered retain their power to anger and inflame, to enlighten and shame. The story of the sorry homecoming still resonates in a culture bereft of public emotions. To take on Vietnam even lightly, is to venture into the no-man’s-land between art and life, imagination and memory, truth and reality. The booby traps are lying in wait; the war is still a free-fire zone. That very danger makes it irresistible.

Vietnam. It brought out the best and the worst in us.

It burns like a blowtorch against the suffocating, self-satisfied web of daily life.

It won’t go away.

II. The Grand Illusion

A patrol slides quietly through tall grass, each man’s eyes flickering and alert. Suddenly, out of the grass comes fire: ambush! Weapons rattle, men scream. And then a helicopter lifts off the wounded to an evacuation hospital near the South China Sea, where doctors and nurses work frantically to save them and to ease the pain of the dying. It’s a scene straight from the war, the terrible nuts and bolts of how it was.

Only this time we’re on the set of China Beach, where I work. The bullets are blanks, the explosions harmless fuller’s earth. The blood is Karo syrup, the wounds latex, the bones cow bones. The terribly burned soldier who dies so heartbreakingly on camera races off to the hospital, still in makeup, to witness the birth of his first child. The dead and wounded play football at lunch.

The blood washes off.

And yet, and yet… when the helicopters start beating with that trademark Vietnam sound and the stretchers and gurneys burst through the door, the wounded screaming, the doctors and the nurses racing around trying to save them, it seems so… real. At first, filming these scenes made me uncomfortable, but each time I feel it less. It’s as if the process of re-creating scenes from the war has laid gauze on my memories and painted them with anesthetic. I’ve been working on China Beach longer than I served in Vietnam. My memories of filmed scenes and real events have become confused. I don’t see the real war so clearly now; on the other hand, I no longer wake up in the middle of the night terrified that I’m back in it either.

Once upon a time… There was a real war where the blood didn’t wash off. The wounded didn’t get up and walk. The paralyzed never made love again. The dead stayed dead. It was a war that wasn’t really a war, that had no beginning and no real end, that no one seemed to want or be responsible for, with no front and no rear and no way to tell who the enemy was, with strange and horrible ways to get sick or wounded or to die, new kinds of drugs, exotic women with black teeth, rock and roll in every foxhole, teenage Baptists gliding through a Buddhist world of spirits and geomancers, where you couldn’t drink the water without putting in pills that made it taste so bad you had to flavor it with grape Kool-Aid-which turned your face purple when you shaved with it.

It was a war where you marched through mud and shit, weighted down with canned food and body armor, inoculated with shots, linked to your world by only a fragile, scratchy radio, farther from home than the astronauts walking, high above you, on the moon, which alone lit the black jungle night. There was fear, dry and metallic, in your mouth one moment, bitter bile the next, and toward your comrades, for whom you would unhesitatingly give your life, there was something like love.

It wasn’t Vietnam we found there, and it wasn’t America, but America-in-Vietnam, a teenager’s zonked fantasy-nightmare of sex, drugs, and rock and roll on full automatic, a civilization part real, part the movies playing in our heads. When things got really bad, we would usually forget our training and fall back on the more indelible images of combat that we got from World War II movies. We loved war movies the way spies love thrillers and mafia dons enjoy The Godfather. They dignified our grubby experience, turned the all-but-unbearable reality into myth.

To John Wayne was a common verb. “Let’s John Wayne it,” or “He got wasted when he John Wayned up the hill.” The movies gave the archetypal images of combat, just as the operatic battle at the end of Platoon—for all Oliver Stone’s antiwar passion—is no doubt playing inside the heads of teenagers today, just as John Wayne played inside ours and we forever confused his movies with our lives. I grew up surrounded by World War II veterans, but John Wayne—who fought his war in the movies—was the real thing.

That confusion of reality and make-believe continues today. Dana Delany, who plays Nurse Colleen McMurphy on China Beach, was so intimidated by the real nurses who help with the series that at first she couldn’t speak to them. “Now they think I was there,” she says. “ ‘You’re one of us now,’ they say, and they seem to want to hear my war stories.” After playing a nurse on television for three years, Delany, for most Americans, is the image of the Vietnam nurse, just as Tom Cruise is Ron Kovic, the hero of Born on the Fourth of July.

“I do feel close to the real nurses,” Delany says. “But there’s something that will always be different about them. Something in the eyes. Like they’ve got a secret.”

Vietnam veterans are a little like the cowboys of the old West: there are not very many of us, but we lived a hell of a story. But what story was that? I’m not sure even the vets know anymore. Years after Robert E. Lee surrendered in Wilmer McLean’s house at Appomattox, an old Civil War veteran was asked to let fly with the Rebel Yell, the fearsome, high-pitched primal scream that had pierced the battlefields like a cry from hell. “It’s impossible,” he said. “Not with false teeth and a full stomach.” It’s impossible to remember the way it really was. We’re too old, too fat, too clean, too safe. And memory has its own agenda. Get two veterans together who witnessed the same event and they’ll argue about what really happened. Rashomon.

Like the other great Vietnam movie of the 1970s, Apocalypse Now, The Deer Hunter hardly tried to confront the experience of the war.

In The Deer Hunter, which won the 1978 Academy Award for Best Picture, three Russian-American steelworkers from Pennsylvania plan to go to Vietnam together. Before they leave for the war, they come upon a Green Beret at a wedding. “What’s it like over there?” Robert De Niro asks him. “Can you tell us anything?” The Green Beret sips his drink and says nothing. Finally, he speaks. “Fuck it,” he says, then downs his drink. They ask more questions. Same reply. Words don’t convey what it’s like. There’s no way I can tell you my stories. You wouldn’t understand. You haven’t been there.

Like the other great Vietnam movie of the 1970s, Apocalypse Now, The Deer Hunter hardly tried to confront the experience of the war. Its central metaphor of Russian roulette was the theme of a grim rondelet of death and suffering rooted in the very core of the steel town back home. Working-class knights in search of a dubious grail, the heroes struggle to hold their friendship together through death, disillusionment, and madness.

In Apocalypse Now the Vietnam soldiers are either stoned-out rock and rollers or psychopathic killers. The hero, Martin Sheen, journeys upriver on a mission to “terminate with extreme prejudice” Marlon Brando, an outstanding American officer driven insane by the war. It’s eerie and primal, a tale of the thin veneer of civilization and the evil beneath, Coppola’s vision of Heart of Darkness overlaid not only on Vietnam but on a savage empire far weirder than anything in the war.

Then came the Chuck Norris/Sylvester Stallone genre films that used Vietnam as a setting for cartoons of glorified violence and adventure. As Rambo, Stallone is abandoned, captured, and tortured, reduced to the ashes of despair so that he can arise to rescue, single-handedly, the American MIAs and, in the process, our damaged honor. It’s silly stuff, an expensive American version of the cheap Italian gladiator film. The movie could have easily been set in the American West, outer space, or 10,000 B.C. Stallone himself was swinging for the mythic fences; he compared Rambo to Don Quixote, and his producers compared Stallone to John Wayne. John Wayne, of course, never played an avenging psychopath, but that just goes to show how much things have changed.

The Duke, however, did make a Vietnam film, one of the first: The Green Berets, a myth made by our myth—Wayne gone fat and sloppy, as confused and out of place as if he’d just wandered in from a World War II set. The movie was equally mixed-up—in one memorable moment the sun set in the east. I saw The Green Berets in Da Nang in 1969 with an audience of marines. It was made to glorify the war, but it was so unreal we were rolling on the ground. Ironically, it was Robert Altman’s comedy M*A*S*H, supposedly about the Korean War, that spoke most directly to us. Hawkeye and Trapper were exactly like members of a marine platoon: they weren’t heroes, just men who would rather be somewhere else, loyal to each other, doing their best in a terrible situation and telling jokes in the face of death.

The most realistic of all Vietnam films is the first half of Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, which wired Marine Corps boot camp with electric-chair voltage and threw the switch. But for me a Vietnam movie’s reality rests on how it portrays the central experience of war: combat. Combat isn’t like anything else. It’s a foreign country where you can’t travel without a passport. As Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote after the Civil War, combat forever distanced him from anyone who hadn’t been there. The memories of combat are dark shadows where the mind can’t wander safely, free-fire zones filled with trip wires, booby traps, ambushes. It’s a private, terrifying world that defies description. The language and images of peace don’t reach it. The cost of combat is the secret that Dana Delany glimpsed in the nurses’ eyes.

Film and television can’t capture combat any more than they can the Holocaust. Combat in most war movies is as stylized as in Henry V. Some films, however, have come close to capturing moments about combat that explode with truth. The ambush on the river in Apocalypse Now is eerily accurate in this way: when the firing starts, the sound seems to disappear; we see the rounds hit, but we don’t hear them. One of our senses is overwhelmed. Sometimes combat was all sound, other times all light: searing, powerful moments that blasted you out of time and space.

A Rumor of War, the television miniseries written by John Sacret Young, was for years the most realistic work about the combat experience. The series takes its time saturating the audience in the heat, the boredom, the anticipation each day of a violent climax that seems never to happen. Hovering over each step into the sucking rice-paddy mud is the soldier’s universal question: “Will I have the courage when the time comes?” Sustained by the powerful bonds of comradeship, the men manage to hang together. But then the inspired leader and best soldier is killed, his death forever destroying any hope that combat might be rational or just. Like an earthquake, it simply is.

It’s no accident that Oliver Stone has come closer than anyone, ever, to putting combat on-screen. Stone fought in Vietnam himself, and he gets it: the glare, the mud, the chaos, the panic, the disorientation, the disembodied radio voices, the sucking-up-your-guts, keeping-a-tight-asshole fear that shoots through you like a force field. I almost couldn’t bear to watch two scenes in Platoon: the first ambush, when Charlie Sheen is asleep and the Vietcong seem to materialize out of the mist, and the assault on the bunker through the mud, bodies slipping and sliding into the muck as if the ground itself can’t wait to bury them.

In Born on the Fourth of July the combat is set not in green jungle but in the yellows and ochers of sand dunes and the grassy highlands of the DMZ. Everything happens in silhouette, as if we were seeing shadows or looking through a scrim, a glass darkly. “See those rifles? See those rifles?” the company commander breathlessly asks. Tom Cruise squints and squints. “Uh, sure,” he says finally. Neither he nor we see them; through him we see only vague shapes, and then with him our fingers squeeze the trigger, that little synapse that is so irreversible. Stone’s powerful visual talent and his bravura camera work are perfectly suited for combat, which is an assault on the senses.

In 84 Charlie Mopic writer-director Patrick Duncan, also a Vietnam veteran, presents combat in a less theatrical way than Stone and shows how offhandedly simple it is for men to die. The camera is quietly there, not commenting but watching. We hear a few pops around the bend, like firecrackers, a yell, then a moan, then nothing. It’s all over before we even notice, but a man is forever dead.

“You know the only trouble with war?” one of the recon soldiers asks in 84 Charlie Mopic. “Too much violence.”

Inside joke.

As fundamental to war as combat is, most Vietnam veterans never saw it. A supply sergeant at Long Binh could spend a whole year without being issued a weapon or hearing a shot fired in anger. He’d have the pleasure of the women, the bars, and the black market, a workingman’s version of the colonial life, all the while in less danger than if he were driving to work every day on the freeway. When I was out in the mountains, such American soldiers were symbols of the people safe in the world that had sent us out here. We hated them, picked fights when we were back, would certainly not risk our lives for them. Their war made no sense; in fact, very little made sense beyond our platoon alone out there in the boonies, lost in space. Star Trek. We loved one another and tried to stay alive. We were in deep shit, and the only way to survive was to help one another until we got out of there. That story made sense. Sort of. No other story did.

But then I was transferred back to the division headquarters and saw firsthand the variety of war experience beyond combat: the doctors and nurses, the generals and colonels, the recreation officers, the dental assistants, rabbit wranglers, military police, civilian businessmen, pacifist volunteers, the reporters and the spies. In spite of my original contempt, I saw that the noncombat experience was real as well—another story to be told, less obvious, maybe in the long run richer. That’s why John Sacret Young and I decided from the beginning to make China Beach a series about the world just over the hill from combat, specifically about the men and women immersed for twelve hours a day in its bloody results, a level of undiluted, industrial-strength horror that few combat veterans witnessed.

Vietnam: I hated it. Vietnam: I loved it. Both are true.

Last year I was on a panel at UCLA with Oliver Stone and Patrick Duncan and filmmakers from the new Vietnam. Outside, hundreds of South Vietnamese refugees were marching and chanting, on the verge of an ugly sixties-style confrontation with the riot police who ringed the building. Inside, other South Vietnamese angrily denounced the Communist filmmakers as propagandists. The North Vietnamese were very polite, but they could afford to be: they won. Oliver Stone wasn’t sympathetic to the South Vietnamese, our former allies.

“When are you people going to stop hating?” he asked. “When are you going to find love in your hearts?”

Many of the South Vietnamese in the audience had fled Vietnam in leaky boats, braved Thai pirates, struggled to build new lives cut off from their own country. Their pain and anger were real, the universal suffering of the refugee. But another part of that anger came from a different source. The South Vietnamese they see in films are bar girls, corrupt officials, cowardly soldiers—hardly the resilient people who have established communities throughout America. They feel left out, forgotten. They are right. Their stories need to be told, just as the stories of the enemy do.

The past changes with the present; we ask it different questions, and the stories we set in the past are the ones that interest us in the present. High Noon was a story of the McCarthyite 1950s, set in the West. Stephen Crane wrote The Red Badge of Courage thirty years after the Civil War with his own demons in mind. Tolstoy wanted to set War and Peace in the 1850s but realized that he couldn’t write about the veterans of the Napoleonic Wars unless he went back fifty years to the wars themselves. The same is true of Vietnam veterans today: Iran-contra is a Vietnam story; the memory of how we betrayed our allies when we fled from Saigon underlay everything Oliver North did. China Beach sprang from a desire, in a self-satisfied, self-obsessed time, to tell the stories of women who twenty years ago risked their lives, without hope of wealth or status, to help others in desperate need.

Vietnam is filled with old stories still to be told, current stories to be revealed, and new ones to be invented. And in the long run, combat, that profound experience at the heart of my own story, may be the least interesting story of all.

III. Beyond Good and Evil

Ron Kovic, the author of Born on the Fourth of July, had just been inspired by James Webb to warn of the “Nazification of Amerika” and to claim that “maybe Hitler is in the White House.” It was 1985, and a roomful of Vietnam writers at the Asia Society in New York City was in the midst of a tumultuous conference about the war and literature, but the political and moral passions that so deeply divided the country kept booby-trapping the topic.

Wounded twice, Webb won the Navy Cross in Vietnam and is the author of Fields of Fire, one of the very best Vietnam novels; at the time of the gathering, he was an assistant secretary of defense on his way to becoming secretary of the navy. A warrior in spirit and an outspoken defender of the war, Webb had battled the Vietnam memorial in Washington (“a black gash of shame”) and once lost the U.S. Naval Academy boxing crown to Oliver North. Webb is a combative man; Kovic wisely timed his outburst for after Webb had departed.

Kovic launched into the tale of his wounding and paralysis, the sort of story that could spellbind an audience of civilians but one that almost everyone in this particular room had either witnessed or lived through. Yet as much as we might have thought we knew it, we couldn’t help being riveted as he talked: the story was so powerful, so poignant, and his telling of it so vivid. Kovic meant the tale to be a refutation of Webb’s defense of the war, the very mention of which had brought back Kovic’s personal trauma and the trauma of America. “I feel my wound now, I feel it….”

I have all my limbs, and it’s hard to argue with a man who doesn’t have all of his. Kovic’s suffering is irrefutable, but it was taking him off the deep end, his powerful emotions losing touch with reality. I was against the war, but Nazis? As Kovic wound down (“look what the war did to me, look at me….”),one writer had the courage to say, “Now, Ron, I think the reference to Hitler may be excessive….”

And then Fred Downs, who wrote The Killing Zone, stood up and waved at Kovic the two hooks that are his hands. “Who gave you the right to pass judgment?” Downs’s steel hands clicked with the intensity of his emotion. “You think”—click, click—“you’re the only one”—click, click—“who suffered?”

A great deal of the rest of the conference disintegrated into shouting matches about whether the war was “unspeakably evil” or whether the excesses and evils of the victorious Communists vindicated our mission there. For a meeting of writers, the topics were stunningly political and concrete. Did the Vietcong have the support of the people or not? Could we, should we, have won?

For all its power, Platoon was like a Greatest Clichés of Vietnam, the most terrible that happened to three million Americans over fifteen years experienced by one platoon in a week.

I used to care about these questions with every fiber of my being. I don’t anymore. The issues that divided Philistines and Israelites four thousand years ago are lost in obscurity, but we are forever inspired by the story of the young Israelite shepherd boy who found the courage to slay a giant with a stone. Stories make art, and art is ultimately what matters. Political certainties don’t make art. Art lives in ambiguity, in the confusion of means and ends, the foggy, chaotic no-man’s-land between good and evil. Absolute clarity about good and evil destroyed Dresden and dropped the atomic bomb on Japan; the ambiguity of art produced Slaughterhouse-Five and Hiroshima, Mon Amour. Politics turns people into abstractions and lets us kill them; art makes them human and lets them live.

What did make Vietnam worse than other wars? What is Ron Kovic so mad about? When Oliver Stone talks about his films, he seems committed to art as a bully pulpit. “If we don’t make films with values,” he says, “then the whole world will be watching Back to the Future Part II.” Thank God Oliver Stone is making movies, since he invariably grinds our faces in scenes we’d rather not watch and takes us places we’d rather not go. But values? What values?

For all its power, Platoon was like a Greatest Clichés of Vietnam, the most terrible that happened to three million Americans over fifteen years experienced by one platoon in a week. In Stone’s film, the American soldiers smoke dope, get drunk, kill babies, rape women, burn villages, murder one another, and generally act like degenerate psychopaths until almost all of them die in a Wagnerian final attack. At the end, the once-innocent soldier Charlie Sheen murders the evil Sergeant Barnes, mimicking Barnes’s murder of the angelic Elias and becoming, in the process, exactly like Barnes. As Sheen is lifted away, he says, in his narrator’s ten-years-later voice, “I think now, looking back, we did not fight the enemy; we fought ourselves, and the enemy was in us.”

Well, I guess that clears up who killed the fifty-eight thousand Americans who died there. We did it to ourselves. And the two million or so dead Vietnamese must have been bystanders caught in some fratricidal olympiad we were playing on a rented field far from home. On the other hand, I do remember someone not us who fired green tracers at us during the night, set the booby traps, crawled through the wire with satchel charges. And I had the distinct impression that those same people turned Vietnam into a police state after we lost, rounded up hundreds of thousands of people for reeducation camps, and prompted millions of their countrymen to risk death in frail boats in order to escape. It’s an example of our egotism as a people that we could even think of taking the credit for such achievements away from the North Vietnamese—who deserve it so much and, in fact, are eager to claim it.

Remove the narration and Platoon is a stunning film about combat and the terribly difficult choices between sort-of-good and sort-of-evil. Lay on the narration and a great movie is smothered under didactic, simplistic politics, not values. If a war story is well told, it doesn’t need anyone to tell you the moral. It’s just there.

In Born on the Fourth of July Ron Kovic is seriously wounded and paralyzed from the chest down. The courage simply to survive in such circumstances is a powerful human value. Suffering can yield great art, but it seldom produces good politics. And politics is what Stone seems to mean by values: the right politics—in this case opposition to the Vietnam War. Kovic is transformed from a fanatic believer in the war into a fanatic opponent. The new man seems as little inclined to sober thought and self-awareness as the old one—he’s merely exchanged one set of blind convictions for another. But instead of screaming for the war, he’s now screaming against it. Only now he’s politically correct.

One of the indelible images from the movie is a chaotic moment in the sand dunes of Vietnam—a moment filled with glare and firing and fear—when Kovic thinks he has shot one of his own men. Guilt-ridden, he goes to Georgia to see the boy’s parents and young wife. He’s there to exorcise his own demons, and with painful detail he tells them how their son and husband died—not for any cause, not doing his duty, not by enemy action, but at the hand of his own sergeant. Kovic leaves feeling unburdened. It’s the turning point of the film; in the next scene he’s leading a demonstration at the Republican convention.

But how does the family feel? Whatever story they had erected to handle the death of their only son and husband, Kovic destroyed. They are left thinking he died for nothing, for a waste. These Georgia crackers are only the means for Kovic’s expiation. He adds to their suffering to help end his own; he wipes his emotional ass with their lives.

Compare this scene to Marlow’s lie at the end of Heart of Darkness. Instead of telling Kurtz’s widow the truth about how her husband descended into savagery, Marlow lies. The lie is a better story and a profound act of human kindness; it leaves the widow with a memory she can live for. Stone and Kovic leave that boy’s family with nothing, only the messiness of Kovic’s guilt and his scream of outrage.

Like many other scenes in this supposedly biographical film, the trip to Georgia never happened. Conservative critics have attacked Stone for making up a story different from the one Ron Kovic originally told, but they are wrong. The film’s story is a better story, more powerful, more cinematic, more universal. Besides, I’m glad Ron Kovic never did such a callous thing. In his guilt the real Kovic fantasized about confronting the family, but to his credit he never did. That story belonged in his own head, not in their lives; to bestow the truth on them would be as cruel and as brutal as tossing a grenade into their living room.

In The Deer Hunter the Vietcong murder an innocent family in its bunker, shoot a woman and child, and torture American prisoners. For the first and, to my memory, only time in a serious film about the war, the Vietcong commit the sorts of atrocities that Platoon and other films have made standard operating procedure for Americans: blowing up villages, killing women and children, mistreating prisoners. The Vietcong did it, over and over, for real. But that reality was embarrassing to fashionable politics, so it has never been shown again.

In Platoon the enemy becomes avenging wraiths, almost otherworldly spirits cleansing from their country the corrupt and evil Americans. In Full Metal Jacket the dedicated, battle-hardened Vietcong and North Vietnamese who took over the city of Hue, fought off a regiment of U.S. Marines, and slaughtered thousands of civilians are reduced to one teenage-girl sniper. To show the enemy as the formidable, ruthless foe he was would be to risk dignifying the men who fought him—and that isn’t the politically acceptable story.

When I returned to Vietnam to meet the men and women I had fought against, they had no interest in talking about My Lai or the deaths of innocent civilians. “We did the same,” one Vietcong veteran told me. “The people were the battlefield. It was tragic that so many died, but it was inevitable.” Of all the Vietcong and North Vietnamese Army veterans I talked to, not one had the slightest guilt for the blood on his hands, and not one expected me to have any guilt for whatever blood might be on mine.

That absolution gave me a great sense of peace—at first. And then I started to realize: I do feel guilty, not necessarily for what I did personally, but for what the war did to their country. The Vietnamese on both sides were fighting for that country. The atrocities they committed were evil and terrible, but they had a reason rooted in some great purpose, right or wrong.

Need a psycho for the hero to blow away? Make him a Vietnam vet—we all get the picture.

At some primitive moral level, their stories made sense. I didn’t think ours did. For all our high motives, Vietnam wasn’t our country, and it wasn’t our war. We could always go home, the way Sam Waterston does in The Killing Fields—listening to opera and feeling guilty while his Cambodian photographer endures the Khmer Rouge genocide. To go to war means to set aside the civilized values and ethics a young man is taught: to kill is good; to die may be necessary. It means leaving home and maybe never coming back. No nation should ask that of its young men without powerfully good reason. Our reasons may have sounded noble, but they felt hollow in the gut. “I never knew a man,” Graham Greene’s narrator says of the American, Pyle, in The Quiet American, “who had better motives for all the trouble he caused.”

Perhaps that’s why the photograph of the bodies lying in the ditch at My Lai strikes us so much more powerfully than images of Dresden or Tokyo, where hundreds of thousands of innocent women and children died in World War II: there doesn’t seem to be a reason for it. It’s war stripped of all purpose, revealing the evil beneath.

The West can’t be understood without John Ford’s vengeful assault on evil Indians in The Searchers and Arthur Penn’s lyric portrait of Indians as utopian victims in Little Big Man. Both versions were true; each spoke to its time. The Vietnam War needs larger truths than those of political fashion. It is, in fact, precisely the ease with which we’ve accepted antiwar orthodoxy that has let political posturing substitute for political thought and kept movies from dramatizing the deeper political realities that led us into this wrongheaded war.

IV. The Homecoming Party

This is a Vietnam movie you haven’t seen. I’m in Venice Beach looking for Butch with three other Vietnam vets: Shad Meshad, Steve Peck, and John Keaveney. Shad has been working with vets for twenty years, Steve makes documentary films, and John, well, when John was living on the street a few years back he tried to kill Shad—but that story comes later. Out of nowhere, Butch appears; he’s in the midst of a typical Venice street quarrel: two men “with guns” are after him. He scans the boardwalk, sifting through the obvious for the one piece out of place, the little detail that could get you killed.

The rest of us have lost those instincts. However rocky our personal paths have been, our war is over. Butch doesn’t go to Vietnam movies; he’s still out there, beyond the frontier, wired into the Death Angel. He has “the look” the movies never get right, concentration-camp body, eyes in distant focus, the look of adrenaline exhaustion you get when combat explodes your brain the way no drugs ever could. The war is still working its way through Butch, like a piece of shrapnel coming to the surface.

Last year Butch and eleven other Vietnam veterans—including one paraplegic to whom LBJ personally gave the Silver Star Medal for bravery at Khe Sanh—were living in Dempsey Dumpsters and alleys in Venice, scrounging for food and alcohol and drugs. They called themselves the Dirty Dozen, their self-image borrowed from the movies of another, better war. In some ways they were like a long-range patrol, bonded together, surviving in the jungle of Venice, protecting one another. Buddies. Tight. But in fact they were prematurely old men, sick and dying, barely able to defend themselves from the predators in Venice or from the deterioration of their own bodies.

For three years John Keaveney lived the street life like the Dirty Dozen. Compact, with a Scotch-Irish brogue, he is perhaps the only man on Venice Beach wearing a shirt and tie. Two days after he returned from Vietnam, he was stopped by the police for driving intoxicated without a photograph on his driver’s license. They tried to put him under arrest, he decided to put them under arrest, a struggle broke out, and before it ended John was facing off much of the Santa Monica Police Department with one of the cops’ own guns.

“I had so much anger,” he recalls. “I felt so cheated. I’d fought there for two years and no one gave a shit. It didn’t make sense, didn’t add up. After that first standoff, things went downhill.”

Strung out on drugs and alcohol, he destroyed a vet center with a sledgehammer and finally held Shad Meshad hostage in his office in the Veterans Administration for almost nine hours. “I thought I was going to die,” Shad says. “The SWAT team was outside, and I was inside with John, who had this thin, flat look in his eyes like he didn’t care anymore. Then finally he passed out.”

John was facing eleven years to life for this assault and other charges. But the charismatic Meshad, a therapist who’s devoted his life to helping his fellow Vietnam veterans, didn’t give up on him, got John out of jail and into a long-term program, and now John, with missionary zeal and undeniable authority, works among homeless vets; he has been invited to help counsel troubled patients as far away as India, patients whose trauma has nothing to do with Vietnam.

One by one the Dirty Dozen died off. Today, a year later, eleven of the twelve are dead. Only Butch is left, living in an abandoned building with his homeless girlfriend. Butch lights a cigarette and grins. His front teeth are missing, and he’s determined to make himself some new ones. “Strange shit,” he says, then shivers. What? “The war. It didn’t make sense. That’s what hurt. It didn’t make sense.”

“Sure the war was fucked up,” John says. “Sure we got screwed. But life’s unfair. You can find excuses to destroy yourself, or you can get it together. They’ve called you incorrigible all your life. They’ve taken away your discharge, your licenses, your paper. They’ve told you you’re a loser. But you’re not. You’ve got something to give.”

“Hey,” Butch says, “I’ve survived. Everyone else is dead. That counts for something. And I’m not on drugs or booze. I’m going to get out of here.”

Everyone lets that lie there for a while. Meshad’s Vietnam Veterans Aid Foundation has plans for a transition house for homeless vets; maybe Butch can help fix it up, teach the other vets some carpentry. Steve and John have to leave. The wind has turned dank and cold.

As Shad and Butch and I are saying good-bye, Butch’s girlfriend comes up, thin and drawn. “Get him out of here,” she says. “He’s got to get out of here.”

Her eyes fill with tears, and she turns and walks away.

Butch watches her go, then looks back at me. “Come on back,” he says. “l’m always on patrol, right here.”

He smiles his toothless grin, then coughs deep in his chest and disappears into the night.

The fate of the returning veteran and its portrayal in film have been as diverse as my story and Butch’s and as schizophrenic as the war itself. In Coming Home—a hipper, more stylized, yet deeply affecting first pass at Born on the Fourth of July—Jon Voight is paralyzed and impotent, the first image of the vet as guilt-ridden victim. He wins Jane Fonda away from Bruce Dern (who is still in Vietnam) and later denounces war and admits his guilt in front of a high-school assembly. Dern is so emotionally crippled—apparently solely because he believes in the war—that the only thing he can do when he returns is commit suicide.

In Taxi Driver Robert De Niro plays Travis Bickle, a loner psychopath who is a Vietnam veteran: no other explanation for his bizarre behavior is considered necessary. Travis Bickle is the prototype of the Vietnam vet on television throughout the 1970s, what Tim O’Brien calls “the junkie violent creepo.” Need a psycho for the hero to blow away? Make him a Vietnam vet—we all get the picture.

That changed when Magnum, P.l. came on the air in 1980. Magnum was no victim or psychopath but a Vietnam vet played as a World War II vet, a good guy returned home with solid values—a hero. Suddenly, Vietnam veterans were everywhere: the good guys on The A-Team, Riptide, Airwolf, and a host of other shows. Putting Vietnam in a character’s back story became the cheap and easy way to give him a weight, a history, a set of values, a code—not to mention well-honed combat skills.

And then there was Miami Vice. Sonny Crockett and Lieutenant Castillo weren’t easygoing good guys like Magnum; they were the vet as terminal cool, fighting the losing war against drugs and vice in Miami the same way they fought the losing war in Vietnam. Life wasn’t about winning and losing, anyway, or even about right and wrong. Forget illusions, forget authority, forget society—all bullshit. You’re loyal to your buddies, and you do what you have to do. Miami Vice was easy existential posturing, as unreal as the earlier psychos had been.

In fact, the vast majority of combat veterans were working-class or hard-core poor—blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, hillbillies, big-city ethnics—by and large good kids who did what their fathers had done: when their country called, they answered—a simple act of patriotism, costing them everything. In my platoon of some fifty men, fewer than ten were high-school graduates; their average age was nineteen, exactly the age of the typical combat soldier in Vietnam. In World War II it was twenty-six. I was twenty-four; my men called me Pops. A lot of them were away from home for the first time. They were still adolescents.

For many of them, like Patrick Duncan, who helped create Vietnam War Story for HBO and who wrote and directed 84 Charlie Mopic, the war was where they grew up. “I was a half-assed juvenile-delinquent loser,” Duncan says. “I went to Vietnam straight from the stockade. But I grew up there. I went there a have-not, angry with the whole system for shutting me out. I left there with a sense of self-worth and purpose. The fact is, I’m a better person for it. Most of the people I know came out of Vietnam better people than they went in. You don’t see that on film. Because we believed so fervently the war was bad, we couldn’t show anything good coming out of it, but it did.”

Most Vietnam veterans I know seem to be vital, successful people with jobs and families. They are heads of corporations, contractors, bankers, lawyers, doctors, nurses, writers. Others are plumbers, carpenters, autoworkers, coal miners, bartenders, the grandfather with his kid in the park, the mechanic in the garage. A Vietnam veteran, Albert Gore, ran in the last presidential election. Another, Bob Kerrey, is a dark horse for 1992.

But for many other Vietnam veterans, the war was a nightmare from which they have never awakened. In Vietnam, for the first time in their lives, they mattered: they counted on their buddies, and their buddies counted on them, the simple, unbreakable bond of combat. And then they left. One moment they were fighting for their lives. The next they were back in America, expected to be “normal” and to fit into a world they no longer knew. They were immigrants from the war zone, and no one spoke their language. The war, which had been their entire world, went on without them, seemingly forever, as if they had never been there.

They were barely past being teenagers; the war was all they had. But the country seemed to hate the war, or just not to care. No one wanted to know about it. They couldn’t tell their stories. And if the war had no value, neither did they. They began to think of themselves as losers, outcasts, suckers. They blamed everyone: protesters, the government, the media, their friends who didn’t serve, their families for not understanding. Or they blamed themselves and wallowed in guilt. It was all too much.

So the Vietnam veteran is also the homeless man in the bus station or in the park, the prison inmate, the dying AIDS patient, the drifter who can’t hold a job. There’s no clear line between the ones who made it and the ones who didn’t. John Keaveney has been on both sides. I look at Butch and I see something of the men I’d been with and something of myself. Each of us contains the ghost of the other.

Born on the Fourth of July is the latest in a long tradition of storytelling about the disillusionment of war, beginning with the Odyssey, in which Odysseus returns home, after sacking Troy, to find his house full of draft dodgers eating his food and trying to steal his wife. Throughout history young men have gone off to war with a spring in their step and returned damaged physically or mentally, almost always to an unhappy welcome.

The fact is, in every war nineteen-year-olds go off to kill and die. The question is, Was all that suffering worth it? If you fought and can find a way to answer that question, you get on with your life. If you can’t answer it, then you have problems. The answer doesn’t have to be yes—it just has to be an answer. Warriors mainly make answers by making stories… about themselves. “Tell my father,” Hammer says in 84 Charlie Mopic, “that I did a good job. I might not have been a hero, but I did the best job I could.”

This story is the workingman’s ethic, purified into a Zen task performed not for some higher purpose but for itself. In the end, most soldiers don’t fight for ideals or for their country anyway; they fight for their buddies. The guys I knew didn’t get out of their foxholes for any abstract reasons. They did it out of love and loyalty and fear of shame. “They would rather die,” Tim O’Brien writes, “than die of embarrassment.”

If your story made sense, however patched together and no matter how deep its internal contradictions, you put the war behind you. I was against the war before I went, and when I got back I marched on the Capitol, on active duty and in uniform, to protest the war. Yet I value the experience more than the two years I spent at Oxford. On one level it makes no sense; on another, it makes all the sense in the world.

But if the story didn’t make sense, no amount of alcohol or drugs could stop it from taking you down with it to an unhappy ending. You gave everything and your country screwed you, made you kill for nothing, wasted your buddies for nothing, betrayed you. And if that story kept hissing and clanging in your head, if the images got out of control and the blood and death took over, then came the anger and suddenly you don’t fit in and no one wants to hire you and you’re in Venice Beach with Butch.

The survivors of World War I were the spiritual ancestors of Vietnam veterans, and its books and movies are eerily resonant of Vietnam. For horror, pointlessness, and utter waste, World War I makes Vietnam look like a back-alley brawl. More men died in one day at the Somme than all the Americans who died in fifteen years in Vietnam. The flower of Europe’s youth fell in artillery barrages heard all the way to London, scythed down by the thousands by machine guns in no-man’s-land, choking on mustard gas; millions more were wounded.

All Quiet on the Western Front is the World War I version of an Oliver Stone movie, a more sensitively and subtly told account of a group of young Germans eagerly marching into the terrible trenches of Flanders. For the young Germans of All Quiet, there is no escape from routine slaughter. No one hears their screams. Futility rips them with the devastation of a machine gun. As the movie makes clear, the war destroyed any connection between them and anyone else. They had traveled beyond the limits of human experience and returned to live out their lives as companions to horror. They were social lepers, trapped in the cage of their own pasts, millions of Ron Kovics.

Like the Vietnam veterans, the Germans lost. Defeat is the wrong ending for a war story; it taunts the memory, it takes the meaning away. The lost war isn’t an affirmation of values; it’s an aberration, a botched civilization, the heap of broken images where the sun beats, an old bitch gone long in the tooth, the foul sack of waste beneath the skin.

In the United States, World War l vets—struggling to breathe with lungs eaten away by mustard gas, nerves destroyed by the most unrelenting bombardments in history—filled hospitals and streets in the 1920s. Ultimately, an army of veterans camped on the Capitol mall, demanding benefits and respect. Those veterans were driven away and their tents burned by troops under the command of Douglas MacArthur and Dwight Eisenhower—who would a few years later demand of millions of young Americans the same sacrifice the World War I veterans had made—in a scene far more violent than anything the Vietnam Veterans Against the War had to endure.

World War II is supposed to have been different, but consider The Best Years of Our Lives, directed by William Wyler from a script by Robert Sherwood. Returned from the war with no hands, the young sailor Homer is consumed with anger because his family and girlfriend feel sorry for him. “They’re either staring at my hands or trying not to stare at them,” he complains. “I just want to be treated like everyone else.” When his girlfriend won’t be driven off, he insists she come upstairs and watch him take off his hooks. The scene is not as graphic as those in the veterans’ hospital in Born on the Fourth of July, but Wyler plays it in real time and deep focus and lets us see real, deep emotions: Homer is thinking of the girl, while Ron Kovic is thinking of himself.

Homer’s friend Fred comes back a war hero with the Distinguished Flying Cross and a bad case of flashbacks and posttraumatic-stress syndrome. He loses his dead-end job as a soda jerk, is abandoned by his wife, and ends up living with his alcoholic father in a shack by the railroad track. No jobs, no houses, no respect—that’s what the World War II vets say they faced. They got their parade, then they were forgotten. For Vietnam vets, it was the opposite: they were forgotten, then they got their parade.

This disillusionment is universal. Steve Peck has filmed a documentary, Heart of the Warrior, about Russian Afghanistan veterans discovering how much they have in common with American Vietnam vets. Shad Meshad led the first session in which Americans and Soviets compared their experiences. And when I returned to Vietnam after the war, I encountered in village after village “heroes of the fatherland” who had nothing to do but tell one another war stories over rice wine in dusty shacks and, later at night, weep for their lost brothers and their own lost dreams.

Movies made in Vietnam since the war have now abandoned the slavish socialist realism of propaganda films and begun to deal with some of the same themes as Born on the Fourth of July. In Brothers and Relations, a 1986 film directed by Tran Vu and Nguyen Huu Luyen, a badly wounded veteran returns home to find that his old friends and relatives don’t want to hear his stories, so obsessed are they with cynical corruption, materialism, and Western fashion. When no one seems interested in going south to reclaim the body of another relative killed in the war, the veteran does, only to discover that the cemetery has been moved, and even his other veteran friends don’t seem to care. At the end of The Deer Hunter, after Christopher Walken’s coffin is lowered into the slag-pile earth, his friends go home and begin to sing, very quietly and very movingly, “God Bless America.” It’s not ironic, it’s not satirical. They mean it. It’s like a cleansing wind. This war may not make sense, but it too shall pass.

In Fourth of July Ron Kovic gets into an argument in a bar with a Marine Corps Korean War veteran who has no sympathy for Kovic’s self-pitying tirades. You asked for it, you got it. Now be a man and live with it. Straight out of The Deer Hunter. He’s supposed to sound callous, but he sounds… right.

There is a line in the movie where Kovic says he’d give up all his values just to be whole again. Severely wounded Vietnam veterans have shown a level of courage and values few of us who are “whole” can imagine. Their examples give hope to the neighbor who lost her child, to a young woman with cancer, to a boy with AIDS, to the wounded, crippled, mentally retarded of the world, just as John Keaveney is an example of hope to Butch and to every other veteran still on the street. Life is suffering and loss, and the people who have walked point in the battle to overcome them have much to teach us.

For example, Bobby Muller was paralyzed in Vietnam as devastatingly as Ron Kovic. Muller shares Kovic’s antiwar politics and sat wheelchair to wheelchair with him at the Republican convention in 1972. But Muller took a different road; he founded the Vietnam Veterans of America and brought tens of thousands of vets out of the closet to help one another. His inspirational story of self-reliance is not the story of Born on the Fourth of July. Ron Kovic gave up his values and still didn’t become whole. And that is the unintentional tragedy within this powerful movie.

It’s true, as Patrick Duncan says, that many men grew up in Vietnam and returned home better human beings than when they left. Chris Buckley wrote in an Esquire article called “Viet Guilt” that he saw in Vietnam veterans “a gentleness I find rare in most others, and beneath it a spiritual sinew that I ascribe to their experience in the war. I don’t think I’ll ever have what they have, the aura of ‘I have been weighed on the scales and not been found wanting.’ ” Susan Jacoby, a feminist author, says in The Wounded Generation that she found “macho” attitudes much more “common among men who spent the war at home than among those who fought in Vietnam. I have often wondered whether the millions of men my age who avoided the draft may feel unmanned in a way that no woman can ever truly understand.”

Senator Bob Kerrey, who won the Medal of Honor in Vietnam, believes that his experience there helped him in politics and in life: “I learned that when you’re ambushed, you have to charge into it, you have to keep on going. And I learned about suffering and pain and how easy it is when you are not in pain to forget those who are.” It’s true that war can instill a sense of courage and loyalty and selflessness, a “count on me” spirit.

Do I want to see movies about Vietnam that extoll those virtues? I used to believe I did. But honestly, no, I don’t. I was lucky. I came home in one piece and got on with my life; the war cost me my first marriage, but, hey, I got to eat fish heads and drink buffalo-wallow water in Thua Thien Province. My story has a happy ending—so far. But my story isn’t the only story. A lot of people I know didn’t come back, or came back damaged forever. As much as I’d like to see my story on the screen, it’s the wrong story.

I hated Born on the Fourth of July, as must be clear by now. It totally rejects those positive values that I and many others—often at great cost—got from the war. It was exploitive emotionally and simpleminded politically. I almost choked on its self-righteousness. Its hero is self-absorbed and pitiful and careless with the feelings of others. But if only one film about Vietnam could survive, I would want Born on the Fourth of July to be it.

No other movie has ever shown so powerfully the cost of war or so demythologized its glories. Boys grow up believing that war is a game and that they can win it. The truth about war is that it’s not a game and that even the best soldiers can die a fool’s death. That lesson has to be learned by every generation. A young Ron Kovic sees that reality as an armless World War II vet marches by him, sad, haunted eyes seeking out the boy on his father’s shoulders. But no young boy, even if he is confronted so plainly with his own future, ever believes such a thing could happen to him. Under fire for the first time, a shocked Prince Rostoff in War and Peace can’t believe the French soldiers are shooting at him. “Is it to kill me? Me, whom everyone loves so?” But they were shooting at him, and they always will be, no matter how well loved he is.

The stories that inspire young men to go off to war are potent and universal and not in short supply. The stories, like Born on the Fourth of July, that might make politicians think twice before sending those young men off to war are more valuable.

V. The Wall

The single most powerful work of art about the Vietnam War is not a movie, a television show, or a book. And its author is not Oliver Stone or Francis Ford Coppola or Stanley Kubrick, but a collaboration among a former private named Jan Scruggs, a West Point graduate named Jack Wheeler, a young architect named Maya Wing Lin, and, most profoundly, fifty-eight thousand Americans who gave their lives in Vietnam. Its official name is the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, but to Vietnam veterans it is simply “the Wall.” I have been coming to Washington, D.C., to see the Wall since it was dedicated back in 1982, coming at all hours of the day and night, in snow, rain, and fog. I have never been there alone.

When I attended the dedication, I was working at Newsweek. I had left Vietnam behind, or so I thought. I had written almost nothing about it; the war was a powerful and vivid part of my life, but so was the birth of my first child. I spent the night before the ceremony at the Wall, me in my three-piece suit and tens of thousands of other guys in fatigues. We stayed up all night telling stories, and when I went back to New York something told me that my life wouldn’t be the same.

A year later I returned and while I was standing by the Wall met Jeff Hiers, my old radioman from the war, who by complete coincidence had come down from Vermont to see the memorial. That meeting started me on a journey that caused me to leave Newsweek and begin a search for understanding about the war that has taken me all over America, back to Vietnam, and into the deepest unmapped terrain of my heart’s own geography.

The Wall is a window, a passage, a reminder in the midst of tourists, traffic, and turmoil that there are mysteries beyond all of us. It is like some sacred place where this world meets the next, where the living meet the dead. It puts us in touch with the fundamental human journey from life to death that is the pattern for all myths and religions. The Wall is a memorial to the cost of war; it is a bill of sale, itemized and totaled. It is eloquent testimony to the biblical injunction that “the paths of glory lead only to the grave.”

As for me, I’m looking forward to men and women born in the 1970s writing or filming the Red Badge of Courage about Vietnam.

No movie ever changed my life; the Wall did. This monument to the dead has a magic power for the living. Those who come to the Wall become part of it. They touch it, rub it, sing to it, pray against it, stare at it—and they talk to it. The Wall is like a character in a play whose silence makes all the other characters speak. And the play is a drama in which millions of visitors have taken part.

Mothers and fathers, children, widows, friends, comrades—they come to the Wall from all over America. Children listen as a woman points out a name, tells a story, then wipes away a tear. A man in a suit makes a rubbing of a name, a tattered bush hat perched on hair gone to gray. He looks too old now to have been so young then, but so does everyone who comes in faded field jackets and bits and pieces of old uniforms. There are as many reasons as there are visitors: some come to remember, some come to mourn, some come to bear witness, some to feel the emotion of the place.

Others come to leave gifts and messages for the dead. One visitor left an invitation to a high-school reunion, another a graduation announcement. There are photographs of family and loved ones, of children grown to adults while the dead slept, of the dead themselves—in a new military uniform or smiling with their buddies, frozen innocently in time.

Whenever someone tells me that all the Vietnam stories have been told and all the movies have been made, I think of the Wall. The long rows of names—so many names—are so specific the effect is overwhelming. The Wall is a mute witness; it tells nothing of how or why death came, in what cause, and with what courage, loyalty, or dedication. The stories behind each name on the Wall could tell us that. The living actors in the theater of the Wall leave clues to those stories beneath the names: letters, poems, essays, notes—as if the dead could read.

“Dear Michael, Your name is here but you are not. I made a rubbing of it, thinking that if I rubbed hard enough I would rub your name off the wall and you would come back to me. I miss you so.”

And: “My dear friends, It is good to touch your names, your memory, and to visit with you. I’ve struggled in your absence. I’ve been so angry that you left me. I miss you so much! I’ve looked for you for so long. How angry I was to find you here—though I knew you would be. I’ve wished so hard I could have saved you.”

And: “So here I am again, left with empty arms and memories. But as my tears fall, I am thankful to God for having had you for twenty-one years and all the remembered love and happiness we shared. I will hold you in my memories and wait for another night when I dream of you again. Mom.”

And: “Cary, I’ll always love you. Linda.”

Cary, I’ll always love you. Linda.

Maybe the last movie about this war of such suffering and death is a love story.

VI. War Without End

Vietnam: I hated it. Vietnam: I loved it. Both are true, so true that for almost twenty years after I came home I lay awake thinking about the war, remembering the faces, hearing the music, smelling those smells of shit and mud and decay and fear.

For those two decades I kept my growing collection of Vietnam books on a prominent shelf. I had a map of the area where I had fought with my platoon. On it I could pick out where we’d set ambushes and had firefights. It was the outward and visible sign of the inner, spiritual map of my memory.

I don’t lie awake anymore. I’ve put the map and the books away. The letters too. Vietnam isn’t a real place anymore. It’s a setting for stories now. It doesn’t belong to me or to any of us who fought there. It’s the property of the people writing Miss Saigon and Air America.

Am I jealous and protective of “my” war when I see these works come out? You bet I am. But there were plenty of Civil War veterans who could have written The Red Badge of Courage. They didn’t. Stephen Crane did, and he wasn’t born when the guns fired on Fort Sumter.

As for me, I’m looking forward to men and women born in the 1970s writing or filming the Red Badge of Courage about Vietnam. And when they do, it won’t be by shouting in our faces or telling us “the truth” about the war, but, by striking deeper, more powerful, universal notes about man—by telling a great story that we can’t ignore or ever forget.

In the meantime, I suppose I’ll sit in the back row, watching all the Vietnam films and muttering, “That’s not the way it was, not the way at all.”