Ever since his first film (Splendor in the Grass) ten years ago, Warren Beatty has been one of the most talked about figures in Hollywood—and the least understood. It is an open secret that the reason Bonnie and Clyde didn’t stand a chance of winning the Best Picture Oscar in 1968, or the Best Actor award (despite both nominations), was because of his controversial status in the movie colony.

He should worry. Today, at thirty-two, he is world-famous, successful, respected, rich (estimates of his total take from Bonnie and Clyde vary from $6,000,000 to $12,000,000), and one of the most eligible bachelors alive. His reputation as a Lothario would make a healthy mink look impotent. But what is he really like? What kind of man is this Warren Beatty?

I first met him in late 1961, when I went to interview one of his famous friends in her suite at the Plaza Hotel in New York. Their romance was still in full flower, so I was not surprised when a door opened and into the living room came Warren, wearing jeans and a rumpled shirt and looking as if he had just got out of bed, which he probably had (it was around noon and the table was laid for breakfast). His famous beautiful young friend introduced us, but Warren only grunted and shuffled out again. I thought him utterly resistible.

“I don’t mind if they make me out a bastard,” he says of the press, “I just don’t want them to make me out an idiot.”

It was about five years and a lot of girls later before I saw Warren again. During the interval I had heard plenty about him, none of it flattering. Whenever his name was mentioned, people reacted with an automatic spasm of resentment. They said, among other things, that he was conceited, arrogant, rude, selfish, pretentious, obnoxious. (I should have figured that anyone universally disliked by so many executives, directors, actors, press agents, and reporters would be interesting, at the very least.) The mildest comment was from a female publicist: “He’s not well liked. He’s not like Cary Grant.”

He sure isn’t. Nor is he easy to interview. Having discovered how easy it is to sound asinine in print if you are misquoted or misinterpreted, Warren has grown increasingly wary of the press. “I don’t mind if they make me out a bastard,” he told me recently, “I just don’t want them to make me out an idiot.” Intense, moody, sensitive, he is basically serious, with no talent for glibness. He doesn’t give pre-packaged answers. Instead, he thinks out what he wants to say—and there are long, awkward pauses while he searches carefully, doggedly, for the word he feels will best express his meaning. But the average reporter couldn’t be less impressed with the Beatty precision of language, because what Warren wants to talk about is his theory of acting and what the reporter wants to talk about is the actor’s sex life.

Warren has consistently refused to discuss his love affairs, a reticence unappreciated in a community whose denizens are wont to telephone columnists to report their romances, their wives’ pregnancies and miscarriages, their marital quarrels, and how much they paid for presents to their loves ones. Warren won’t play the kiss-and-tell game. “One of my few virtues is discretion,” he says. He carries the practice of this virtue to such extremes that he riles people who don’t understand his motives. A male writer who interviewed Leslie Caron at the time of her romance with Warren had the same experience I had at the Plaza. “He never even spoke to me,” the writer said indignantly. “He just walked out of the room.” I realize how that in each case Warren’s behavior did not stem from an insolent lack of courtesy, but from dismay at having walked into a press interview with an actress with whom he was having an affair and his determination not to contribute in any way to publicity about the romance.

Warren’s desire for privacy in this personal area has been frustrated, in part, by the fact that his prowess as a lover has, until recently, overshadowed his skill as an actor. Without intending any disparagement of the women involved, it should be pointed out that one doesn’t have to be Superman to be successful with girls in Hollywood. Warren may not be the only unquestionably heterosexual male in town, but the field has not been exactly overcrowded. So, not surprisingly, he has gained a reputation as the year-round champion stud of the film colony, a sobriquet that hasn’t necessarily endeared him to men of more mediocre—or ambivalent—sexual ratings.

Nevertheless, whatever the competition—or lack of it—the Beatty myth has grown. In her book Scratch an Actor Sheilah Graham, the famous Hollywood columnist, wrote, “The girls he has loved, famous or unknown, are legion”; and last year an article in Life contained the flat statement: “With Warren Beatty there is no worry over whether seduction is possible, only when and where and who’s next.” Certainly, the list of women with whom his name has been linked is a glittering one, and includes Joan Collins, Natalie Wood, Vivien Leigh, Lesli Caron, Vanessa Redgrave, Barbara Harris, Candice Bergen, Inger Stevens, the Russian ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, Madame Dewi Sukarno, and, of course, Julie Christie.

Not everyone succumbs to Warren’s charm, but his record is such that if he is seen talking at length to any girl, people assume a subsequent bedroom scene is inevitable. Last year gossip columnists reported that he had left Julie Christie for Brigitte Bardot. I asked him about the alleged affair and he said, “I’ve met Brigitte exactly twice, both times in public. I’ve never seen her alone.”

As for Mme. Sukarno, the beautiful, estranged wife of the former Indonesian President, she met Warren at a party in Paris given by Mia and Louis Feraud, the designers. According to a guest at the party, Mme. Sukarno did indeed appear smitten with Warren: “She did everything to attract him and she certainly looked gorgeous … practically exploding out of a low dress—no man could have ignored her. She made a spectacular exit, wearing a floor-length brocaded cape and carrying a long bamboo pole with a lighted candle on the end—don’t ask me why. But Warren didn’t leave with her. I don’t know if he ever saw her again, but if he did, he isn’t going to say so.”

Warren in bed is said to be living proof of the old adage that practice makes perfect. In fact, it’s been reputed that he’s practiced his way to absolute perfection. But how does he get the girls there in the first place? Faye Dunaway, one of those he did not becomes involved with him, possibly because she was too much in love with someone else at the time she and Warren played Bonnie and Clyde, has been quoted as saying that the secret of Warren’s appeal is his “totally unconventional approach to women. It’s a direct approach. He plays it for shock. He doesn’t waste time on amenities.”

Faye’s assessment tallies with a report of a photographer who told me, “I’ve seen him go up to strange girls and say, ‘I’m Warren Beatty. How would you like to sleep with me?’” I repeated the anecdote to Warren and he laughed. “For Christ’s sake, it’s the old joke,” he said. “You know the one: a guy goes up to girls and says, ‘How would you like to go to bed with me?’ and a friend asks him, ‘Don’t you get your face slapped a lot?’ and the guy says, ‘Yes, but you’d be surprised how often I make out.’ ”

“You mean you don’t operate that way?” I asked?

“Don’t be silly,” he said.

Although personally I don’t dig the Beatty kind of looks—too boyish, the type of adolescent male face you see everywhere—I can understand why most women would think him devastatingly handsome. He’s tall—six one—has a good build, and quizzical, deep-set, blue-green eyes under shaggy eyebrows, a dimpled chin, and a sensual mouth with full lower lip. The habit of narrowing his eyes and baring his bottom teeth I guess is sexy, and he has a really warm, dazzling smile, although he doesn’t use it often. Bob Benton, who along with Dave Newman, wrote the screenplay of Bonnie and Clyde, told me that girls fall apart when they see Warren on the street: “He has this fantastic thing with women. If he looks at them and smiles, they collapse, sometimes in tears. They’re overcome.”

Once or twice I caught an inkling of how Warren’s appeal works. We had an argument that grew out of a previous interview, and one day I stormed into his suite at New York’s Delmonico’s Hotel, huffily saying what I thought of him. He was striding up and down the room and suddenly he yelled at me: “Will you sit down and shut up and listen to what I have to say?” I sat down and shut up and listened. “Hmmm,” I thought. “This kid has more to him than I’d given him credit for.” I hadn’t expected his reaction to be so honest and direct and human. He wasn’t a movie star intent on his image, spraying push-button charm at the interviewer. He didn’t try to fob me off with evasive tact. Instead, he met the issue—the source of our disagreement—head-on. Among the many plastic narcissists of the film world, Warren’s real-life masculinity must provide an often riveting contrast.

The first interview I ever had with him took place in his penthouse suite atop Los Angeles’ Beverly Wilshire. He likes living in hotels: “I have no cook, no maid, no butler, no valet, no secretary, no chauffeur. Nobody else up here … just me. And I like it this way.” The room was in disorder, with stacked books on the coffee table and piles of records spilling off the couch and chairs onto the floor. He keeps books stashed in all the hotels where he stays in different cities, and when he’s in New York for more than two weeks, he gets Delmonico’s to move their dining-room piano into his suite so he can play when he feels like it. He’s certainly not acquisitive. He has only one car, a black Lincoln convertible. “My entire adjustment to cars is very square. I just like them to have soft seats and good engines and radios. I don’t care for spritzing around.” Nor does he have a big wardrobe, and he’s not a collector of luxury gadgets or cultural status totem: “I have practically no possessions, but I have difficult throwing anything away. I clip things from newspapers and magazines and save them, and then they pile up and I hate to throw them out.”

Warren is bright, but he isn’t that bright, and it doesn’t help him any when others try to oversell him. On his own he can be immensely likable and appealing.

Warren had been up until five in the morning and I’d waked him at eleven, but he was cheerful and friendly. He wore a clean white shirt with the top buttons undone, charcoal-gray slacks, a black cardigan, black loafers. Going to the phone, he ordered breakfast: grapefruit, yogurt, eggs, and toast. (No gourmet, Warren likes meals consisting of sandwiches and a bottle of ginger ale. He stays away from alcohol, and on those rare occasions when he lights a cigarette, he doesn’t inhale and takes only a few puffs before he puts it out.)

Before breakfast arrived Warren started asking me questions about my life, and I had a hard time getting him to talk about himself. This reversal of roles is a studied technique on his part by which would-be interviewers wind up telling him their own life histories, go away thinking what a great guy Beatty is, and then get home and look at their notes and realize they don’t have anything. Warren distrusts all journalists and says he is fed up with being asked questions he considers silly or superficial or too personal. He once yawed in the face of a Saturday Evening Post writer and said, “I’ve given you too much of my time, much too much. You haven’t asked me a single question about my ideas on acting … or anything I consider important … All you’re interested in is trivia.”

I expected to dislike Warren Beatty this time because of my first impression during the interview with his friend at the Plaza, and also because his Hollywood press agent had said to me on the telephone, “This is the brightest guy you’ll ever meet in your life!”—a remark which instantly fired my hostility. (Warren’s associates have an unfortunate reluctance to let you discover his intelligences for yourself. A production man on Bonnie and Clyde told me, “What separates him from other actors is his brain!” and a friend Warren suggested I call in London kept repeating like a stuck record, “He’s so bright … Christ, this guy is bright.”) Warren is bright, but he isn’t that bright, and it doesn’t help him any when others try to oversell him. On his own he can be immensely likable and appealing.

To his credit, he is disarmingly modest when you meet him. He doesn’t boast or volunteer self-congratulatory items. In fact, he doesn’t volunteer any information; you have to extract it. I experienced an example of this Beatty reticence when I saw him again a couple of weeks later in New York, knowing he had been invited to the White House by President and Mrs. Johnson—to a dinner in honor of Princess Irene of Greece. (I would never have learned about the invitation from him; his press agent had told me.) “I heard you’re going to the dinner at the White House,” I began.

“Who the hell told you that?” Warren was visibly annoyed.

“John did.”

“Oh.” Then silence.

“Well”—I asked—“how did it happen?”

“I’m invited to dinner, that’s all. Is there anything wrong with going to dinner at the White House?”

“No, of course not. But it is one of those semi-official cultural gatherings or it is just a social affair?”

“It’s just a social affair.”

“Do you know the Johnsons?”

“I don’t know know them. I’ve met them.” That was all I could get out of him. (I didn’t even learn the dinner was for Princess Irene until I read it in the papers.) But the point I want to make is that a few hours later, during lunch, he took several telephone calls from friends and not once did he mention the White House dinner. He just said he had to go to Washington and would be back the next day. I don’t know anyone else who would have shown such restraint.

“I have a certain truculence about not doing things I don’t think are right for me,” he said.

At the time of the Beverly Wilshire interview Warren had just finished shooting Bonnie & Clyde and no one had any idea of the smashing triumph it would be. In the seven years he had been in films he had made only seven pictures (B&C was the eighth) and turned down more roles than possibly any other actor in history. “I have a certain truculence about not doing things I don’t think are right for me,” he said. It is easy to understand how Warren’s choosiness has annoyed the Hollywood Establishment—because, as Arthur Penn, who directed B&C, pointed out to me, “If people keep offering you fat parts and you keep turning them down, the implication is you think their taste is lousy.”

Penn had also directed Warren some years before in Mickey One, a curious, fascinating, frustrating film (Warren calls it “a complicated, brave picture that failed”) and Penn is characteristic of the people who do like Warren. (Lillian Hellman, who suffers gladly neither fools nor phonies, is another who admires him.) “I saw Warren in The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone,” Penn told me, “and took the script of Mickey One to him at Delmonico’s. I thought him a very attractive young man—deeply confused, but attractive. He had a reputation for being uncooperative and difficult, but overall, it was a pleasant experience to work with him. I never found him lacking in a willingness to engage, and I think that an admirable trait. He has a strong native intelligence and a richly inventive mind. Oddly, his literary taste is exquisite—not from any broadly educated base, but from a visceral appreciation of good writing … He’s not a frivolous person; he’s profoundly responsible. I don’t think anyone can question his integrity, and I would take his word on anything.”

Warren was born March 30, 1937, in Richmond, Virginia, but he grew up in Arlington. His father, Ira O. Beaty (Warren added the extra “t” so the name would be pronounced “Batey” instead of “Beety”), used to be a teacher of educational psychology and philosophy (he’s now in the real-estate business) and his mother taught acting and directed local amateur theatre groups. In high school Warren played basketball and baseball and was star center on the football team. He was offered ten scholarships to as many colleges but turned them all down to go to Northwestern University’s School of Speech. Quitting before the year was out, he went to New York in 1956, determined to be an actor. A cheap furnished room was his Manhattan home, and his job as sandhog on the construction of the Lincoln Tunnel paid the bills while Warren studied acting with Stella Adler. He auditioned for a “Kraft Theatre” television play and got the lead, the role of a young vagabond rebel. After that he did other TV plays and winter stock in New Jersey, picking up extra money and playing the piano in a New York bar and in what he calls “gin mills and dumps on Long Island.”

Director Josh Logan and playwright William Inge saw Warren perform on television and gave him a screen test (on viewing the results Logan said, “this boy is the sexiest thing around”)‚ which led to MGM’s signing him for a film that was never made. Then, in November 1960, Warren opened on Broadway in Inge’s play, A Loss of Roses—a short-lived flop, but Warren received unanimous critical praise and through Inge met Elia Kazan, who signed him to play the lead opposite Natalie Wood in Splendor in the Grass. The movie opened in 1961, and Warren’s reviews were again spectacular; he was acclaimed as the successor to James Dean and Marlon Brando, and Life called him “the most exciting American male in movies.”

He was then twenty-three-years old, had been a star in his first play, and was a star in his first movie—literally an overnight success in both. Further, Warren had risen to the top entirely on his own, as he had determined to do without any assistance from his older sister, Shirley MacLaine, who by then was an established actress. He has a stubborn inner probity, I feel, which makes him reject the easy way, the quick money, the professional short cut—and this reliance on self has often been misinterpreted as arrogance by those less close to him.

While his career languished, Warren’s private life flourished, and though he never talked about his love affairs, everyone else did.

That initial year in Hollywood Warren made two other films, and then turned down the first of many roles, which, as I mentioned before, alienated the money men around town and earned the actor a reputation as a bumptious young smarty-pants. Among the movies he rejected were The Victors, West Side Story, Act One, The Carpetbaggers, Youngblood Hawke, and PT 109 (he was John F. Kennedy’s choice to play in the film version of the President’s written wartime experiences). When I asked him about turning down the JFK part, he told me, “Frankly, I get embarrassed when people say, ‘Why didn’t you do it?’ I’d been saying no to so many pictures because I thought they were crap, and I hadn’t worked for two years. It was getting almost ludicrous … I’d turned down two million dollars and hadn’t made a cent. Then Jack Warner asked me if I would fly to Washington and meet with President Kennedy. I didn’t think 109 would make a good picture and I felt if I read the script later and didn’t like it, I couldn’t say no to the part after I’d already met the President and discussed it with him. So I said I wouldn’t fly to Washington. Someone in the office said, ‘Why not fly the President to Hollywood?’ He meant it as a joke, but a newspaper columnist printed the line and claimed I had said it. I was terribly upset. Later, when I did meet President Kennedy on another occasion, he was very funny about that.” (Cliff Robertson was in the film, finally.)

While his career languished, Warren’s private life flourished, and though he never talked about his love affairs, everyone else did. The general tone of commentary was an equal mixture of malice and envy, but Warren’s girls were devoted and loyal, and remained so even after he left them. To this day, none of them will talk about him, not out of any feelings of hostility, but apparently because they respected and admired (as well as loved) him.

Warren is not your typical philanderer. Indeed, I would think his earnest, innate decency would lend any affair an aura of dignity which would be reassuring to the female ego. Women have left their husbands and lovers for him and, according to their friends, have never regretted it, although “transitory” is the qualifying Beatty adjective for romance. When Joan Collins was making a film in Europe, she flew back to America three times to see Warren, but during that period he switched to Natalie Wood, who was still married to Robert Wagner. Natalie followed Warren to Miami, where he was making All Fall Down, and everyone expected her to marry him after her divorce—but once again the lover moved on. When Warren was filming Mickey One in Chicago, Leslie Caron flew there every weekend to be with him, and when Leslie made a picture in Jamaica, Warren was on hand to keep her company off the set. Her husband, Peter Hall, then director of the Royal Shakespeare Company in England, divorced Leslie, naming Warren as correspondent, but again an expected marriage did not take place. When I asked Warren about his reluctance to take a wife, he said, “I don’t know why it’s anyone’s business or why people should get so indignant. They say, ‘He never marries the girls.’ Well, it so happens none of the girls wanted to get married. As for myself, I have an ambivalent attitude toward marriage. I’m not against it, but I’m not especially for it.”

A man who knows Warren fairly well said, “I’ve felt at times he’s been somewhat envious of people like myself who are reasonably happily married. His inclinations are toward a home and roots, but his pattern of living out of a suitcase is heavily ingrained. Besides, Warren sees these God-awful examples of broken marriages everywhere among actors. He’s extremely aware of what this business does to a man and wife. Then, too, he has a big ego—and he’s aware of that, also. I think he’ll keep on his own style until he gets halfway satisfied with his professional achievements. Ever since Bonnie and Clyde, his problem has been, ‘How do I follow it?’ I think if he hadn’t made that picture, he would have married Julie [Christie]. They compliment each other. They really admire each other, and the ego thing gets dispelled when they’re together.”

Warren started going with Julie in 1967, while she was making Petulia in San Francisco (“When I met her,” he told me, “I thought she had the most wonderful face!”) According to reports, he was in town at the time visiting a Russian ballerina who was staying in California, while Julie was still in love with Don Bessant, the English painter with whom she had been living for several years and who had flown over from London (peripatetic people!) to see her. (I met Julie and Don four years ago in Spain, when they were on vacation in a small Costa Brava fishing village. “I cannot imagine not being in love with Don,” she told me then. “I also can’t imagine a time when I wouldn’t be with him. But—forever? I don’t honestly know. Forever is a long, long time.” Indeed it is.) At first Julie did not appear interested in Warren, but the ballerina went on tour and Don returned to London—and Warren stayed in town. The next anyone knew, actor and actress were with each other in Mexico, and they’ve been together ever since—although no one is taking bets on permanence.

I saw Warren several times last year in Paris, where he was filming The Only Game in Town with Elizabeth Taylor, his first picture since B&C. I asked why he decided to accept that film after having turned down so many other good offers, and he said, “The people are extremely pleasant and I get weekends off.” (An unusually flimsy answer for Warren!) Only Game is about a love affair between a compulsive gambler and a nightclub dancer in Las Vegas. Frank Sinatra was originally signed for the movie, but when Elizabeth had to postpone filming because of her hysterectomy, Sinatra had to keep other commitments and Warren agreed to replaced him. His reason for taking the job may have been the realization that he couldn’t wait forever for something spectacular with which to follow B&C, and that the longer he waited, the more difficult it might became to make a choice.

Warren still wants to produce, direct, and star in a film he has written and on which he has been working, off and on, for the last few years. “I was set to start filming in Prague,” he told me, “and then came the Russian invasion. I’m now thinking of trying it in Russia and Yugoslavia. In the meantime, this is an agreeable job in Paris. Elizabeth is sympathetic, straightforward, and ethical. Working with her is one of the most pleasant associations I’ve had.”

Julie was in Paris with Warren when I saw him, but he wouldn’t let me talk to her. I heard that she made only a couple of visits to the film set—and had lunch in Warren’s dressing room. The rest of the time that he was working, she amused herself by visiting antique shops and the Flea Market. “We seldom go to parties,” Warren said. “No discotheques or nightclubs. We like good restaurants where we can sit and talk. Most of our time is spent alone. I’m studying Russian and French, and we’re being very quiet.”

The last time I saw Warren in Paris we met in the bar of the Hotel George V, where he and Julie were staying. He suggested we get something to eat and we tried four restaurants in the neighborhood, but they were either closed (it was Sunday) or not serving dinner because it was too early. We finally went back to the hotel bar, where Warren tried to order sandwiches. No luck—they wouldn’t serve food in the bar—so again we got up and moved out to the lounge. The only reason to mention this little episode is to illustrated how good-natured and pleasant Warren was throughout. Contrary to what journalists have written, he doesn’t throw his weight around or demand special attention. There is no movie star grandezza about him.

“I’ve decided not to give any more interviews. I’m seeing you because I promised I would.”

We spent a couple of hours together and Warren was willing to talk about anything except his personal life. He is seriously interested in politics and national affairs, civil rights, the student revolution, and the war against poverty. On all these issues his views are liberal and humane, reflecting an intelligent effort to keep informed. (When asked to do television appeals for VISTA—the domestic Peace Corps—he first visited Los Angeles’ black neighborhood of Watts, telling the VISTA people, “I’d be happy to help you, but I must learn about your program and see if I really believe what I’m saying about it. I’ll be sort of a pain to you, because I have to make sure I really believe in what you’re doing.’) He knew and liked Bobby Kennedy, for whom he campaigned in California and Oregon, and after the assassination he traveled around the country making speeches in favor of gun-control legislation. Warren also attended the Democratic Convention in Chicago in 1968 and has firm opinions on various politicians (Carl Stokes, the black mayor of Cleveland: “A terrific man … charming, intelligent … a serious, good man.” Teddy Kennedy: “Here we’re dealing with someone whose potential appeal is unlimited.”)

Conversation with Warren is interesting and uninhibited—so long as you can stay off the subject of his personal life. Before I left him I asked him again why I couldn’t see him with Julie. “Because it’s a private relationship,” he said. “Anyway, I’ve decided not to give any more interviews. I’m seeing you because I promised I would, but I’m not going to bring Julie into it. If she and I were making a movie together and I thought our being interviewed together would help the film, it might be different.” (Since then, Warren has visited Russia in connection with filming his own script, and recently it was announced that he and Julie would star in the picture together, although when I saw him last, he thought she wouldn’t be in it.*)

One notable thing about Warren is that his triumph with Bonnie and Clyde—which enhanced his professional reputation and filled his coffers—doesn’t seem to have changed him. He has always insisted on doing what he felt was right for him; the only difference is that now he can well afford such independence. He remains basically the same person—honorable, talented, and intransigent, but with a knack for arousing antagonism, chiefly in members of his own sex.

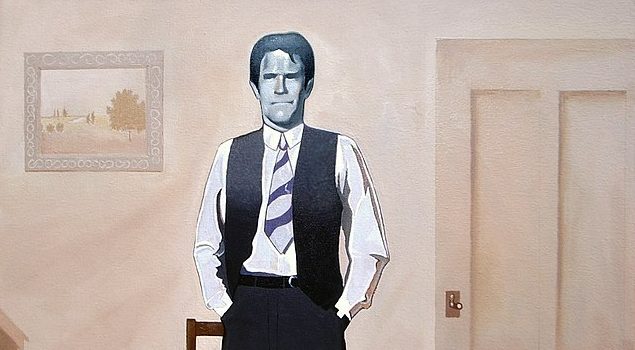

[Painting Credit: Blaine White via Wikimedia Commons]

* That movie a decade later became Reds with Diane Keaton in the lead role.