It’s hard to think back on this story now without sadness. You hear so often about some running back who could have been the greatest. Well, Marcus really was the greatest, or at least he could have been. I’ve never seen anyone like him.

Willie Morris and I became close friends as the result of this story; he died on August 2, 1999, two days before he was going to take my daughter, Maggie, and me to the premiere of the film made from his wonderful book, My Dog Skip.

Marcus Dupree tried to make a brief comeback with the Los Angeles Rams in 1990 and 1991. He gained 251 yards over those two seasons, scoring one touchdown before packing it in. He’s now a minor entry in the NFL record book. This past July Marcus joined the Washington Redskins as a college scout in charge of the Southwest.

If Marcus Dupree’s story was a fairy tale, it would read like this: “Once upon a time in a strife-torn village in Mississippi called Philadelphia, a boy was born into hardship. Black and poor, growing up in the most racially segregated state in the union, he scarcely knew his father. His younger brother Reggie was crippled. The circumstances of Marcus’s life, though, were not all dictated by a dark star. He had some things going for him. In high school he was well over six feet and 220 pounds, powerful, swift, and agile, and in the newly integrated South these were valuable things to be, being prerequisites for stardom in football, a ticket to education, and possibly even wealth.

“And so, Marcus grew up in a spotlight, shattering the records of all players who had come before him, black and white, and becoming the idol of thousands of young Mississippi boys, both black and white. To his fans he was more than just a great football player: Marcus was a symbol of unity for a state that had been struggling for a century to heal the scars of racial hatred.

“When the time came for Marcus to choose a college, he was the most sought-after high school player the nation had ever known. In a spectacle that bewildered those who knew nothing about football—and even many who did—he was wooed, harassed, and begged by grown men from Southern Cal and Pitt and Ohio State and Alabama and UCLA and Texas and even Ole Miss (who might have had a better chance if their nickname hadn’t been the Rebels and their symbol a Confederate flag). They pursued him as if their failure to get a seventeen-year-old boy to play ball at their university could cost them their jobs—which, in fact it well may have, for the scouting and recruiting of athletes like Marcus had become a high-powered, cutthroat business that bore more relation to industrial espionage than to any ideal of athletics the universities professed to uphold.

“Finally, after creating enough suspense to keep a corps of sportswriters employed for a month, Marcus chose Oklahoma, land of Heisman Trophy winners and national champions. The coach, Barry Switzer, changed the team’s offensive formation to accommodate Marcus, something he hadn’t even done for the great Billy Sims. Dupree had a spectacular freshman year, and experts predicted he would go Archie Griffin one better by winning the Heisman Trophy three times before he was through. A noted author wrote a critically acclaimed book about Dupree’s life and exploits up to age nineteen, a book which made Marcus famous in sophisticated places like New York where they didn’t even have college football (or at least not the kind people in Mississippi called college football).

“He led his school to victories over hated rivals Texas and Nebraska and eventually to a national title on New Year’s Day in the Orange Bowl, where, before a national TV audience, he joined the pantheon of college football gods—names such as Red Grange, Davis and Blanchard, and O. J. Simpson. He was signed by the National Football League’s New Orleans Saints, who mortgaged the Superdome to get the rights to him, knowing that they couldn’t afford to let this once-in-a-lifetime-local-legend-turned-national hero be lured to the upstart United States Football League. Besides, everyone remembered the sad fate of Herschel Walker, a once-promising college running back now reduced to returning punts before a few hundred fans. No one wanted Marcus to wind up on a team that might move to somewhere like Bismarck, North Dakota, or Portland, Oregon.

Marcus Dupree must finally deliver on the claims of greatness made in his behalf.

“The Saints’ gamble paid off when Marcus led them to the ultimate championship in football, the Super Bowl, a game no New Orleans Saint had ever been to without buying a ticket. President Mario Cuomo asked him to the White House for a soul food dinner; Howard Cosell rejoined Monday Night Football just to broadcast his games and even managed to accent the right syllable when pronouncing his name (though he never got over the habit of saying ‘Du-pray’ instead of ‘Du-pree’). Marcus retired even younger than Jimmy Brown had, after smashing all the records of fellow Mississippian Walter Payton, and starred as himself in The Marcus Dupree Story with Jayne Kennedy, which some called the best movie about football since Knute Rockne, All-American. And then, at age thirty-five, and only thirty-six years after the tragedies of the civil rights murders in his hometown, he became the first black governor in Mississippi history.”

If you follow football, you know exactly where this fairy tale parted with fact. If the fortunes of Marcus Dupree had been just a little different, if everyone involved in his saga, from Marcus on down to his friends, fans, and coaches, had been better prepared for the complexities of his situation and the extraordinary possibilities he embodied—who can say what paths his story might have taken? Two years ago, did anything seem beyond the reach of this fabulously talented teenager with the storybook background? A screenwriter submitting a script of Dupree’s life up to his first year at Oklahoma would have been laughed out of the office of any respectable producer. One can easily picture the scene: “C’mon now, he’s black and he’s from Mississippi and he breaks all the national high school records? And his brother’s got cerebral palsy? Even the public that swallowed Rocky III wouldn’t buy that.”

Now, only two years later and still several months from his twenty-first birthday, Marcus Dupree is at the crossroads. Although he is beginning his second year as a professional, his fame and his reputation as a running back rest upon a relative handful of college games played nearly two years ago. There are questions about injuries and about his attitude that can no longer be put off with references to his youth and background.

Far from the familiar faces of Philadelphia, in chilly, rainy Portland—a part of the country not exactly synonymous with great rushing performance—Marcus Dupree must finally deliver on the claims of greatness made in his behalf.

If the 1985 season is spent nursing injuries not readily apparent to observers, if he should find Portland too unsympathetic toward a twenty-year-old who is expected to carry a second-division team—if the opposition just plain intimidates him with the relentless keying and merciless gang-tackling they will almost certainly try until he proves to them that such tactics cannot stop him—then Marcus Dupree, perhaps the premier football talent of his generation, could well join such other star-crossed names as Billy Cannon, Tommy Nobis, and Ernie Davis, for whom greatness seemed inevitable and whose names cannot be recalled how without bittersweet reflections on what might have been.

The publicity accorded in recent years to passers such as Doug Flutie, John Elway, and Jim McMahon has tended to obscure the fact that in college ball the running game still dominates. With the exception of Brigham Young last year which played the weakest schedule of any national champion in two decades and Penn State in ‘82 (which had running backs Curt Warner and Jon Williams in addition to quarterback Todd Blackledge), one is hard-pressed to find a national collegiate champion in the postwar period that didn’t rely overwhelmingly on the ground attack.

In fact, it’s been thirty-seven years since a Heisman Trophy-winning quarterback (Johnny Lujack of Notre Dame) led his school to a national title. Since O. J. Simpson won the trophy in ‘67, fourteen Heisman winners have been running backs; two of these Heisman winners played for national champions, and three other schools that won the national title had a future Heisman runner on the roster. You don’t have to have a degree from M.I.T., to figure out that the quickest way to make a run at the national title is to find the best runner available and surround him with good blockers.

It hasn’t always been so simple. As late as the early ‘60s football was still a limited-substitution, one-platoon game that demanded multi-skills from its participants. “He can run and kick and throw” was the description of the ideal football hero in the old college song Mr. Touchdown. But unlimited substitution made versatile players superfluous; 1956 Heisman Trophy winner Paul Hornung—a fine runner, blocker, kicker, passer, and tackler—might have a hard time finding a starting position in today’s game. Football has become a game of single-skill specialists, and nowhere is the change more apparent than at halfback—a word that has almost vanished from college ball, giving way to tailback.

The tailback is both the workhorse and the glamour boy of modern football. In any other formation, you might lose track of the ball carrier, but in the “I” the tailback is unmistakable, all alone and so far behind the line that an old-timer seeing a modern game for the first time might think the tailback was in punt formation. He’s a one-man Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside, carrying the ball straight into the jaws of massive defensive linemen—something the swivel-hipped halfbacks of yore were seldom called on to do—and on the next play streaking the way the legendary fullbacks couldn’t.

Every great back of the last few decades has his rabid defenders when it comes to arguments over who’s the greatest. Marcus Dupree has the potential to be better than all of them.

Beginning with Simpson, a breed of tailback faster and stronger than almost anyone of earlier eras began to emerge. In rapid succession there were Steve Owens, Anthony Davis, John Cappelletti, Archie Griffin, Joe Washington, Ricky Bell, Tony Dorsett, Earl Campbell, Billy Sims, Charles White, Marcus Allen, George Rogers, Curt Warner, and finally, the ultimate tailback, Georgia’s Herschel Walker—or so Walker seemed the ultimate tailback. Walker looked like the end of the evolutionary line, the limit to how far humans could develop in so short a time. Standing just under six-foot-two and weighing around 215 pounds, he could run a forty in a shade over 4.4, faster than almost any defensive back trying to run him down and a good twenty-five pounds heavier than one who could. Until bionics would be perfected, nothing could surpass Herschel Walker.

Until Marcus Dupree. At about six-foot-three, Marcus has at least an inch on Walker; at a freshman college weight of around 235, Marcus carries a good fifteen to twenty pounds more than Herschel. Every great back of the last few decades has his rabid defenders when it comes to arguments over who’s the greatest. Marcus Dupree has the potential to be better than all of them. He broke Walker’s record with eighty-six touchdowns before his freshman year at Oklahoma. Against opposition that was supposed to prove to him that high school statistics don’t count with the big boys, he averaged a breathtaking 7.8 yards a carry. (Billy Sims, the year he won the Heisman Trophy, averaged under five.) In his astonishing Fiesta Bowl appearance Dupree amassed 239 yards on just seventeen carries.

The amazing point about his yards-per-try averages in college is that they were run up by a back coming out of the “I” formation. It’s not unusual for a good runner in a wishbone attack to average six yards or better, since the opposition can never be certain when or where he’ll get the ball, and in any event the wishbone is designed to get the ball to a good back in the open. That’s not true in the “I” formation, where the defense always knows who will get the ball. Defenses knew Herschel Walker was coming and yet he ran over, around, and through them at a clip of five yards a carry; Marcus Dupree, when his college career ended, was averaging more than seven.

Just how good is Marcus Dupree? Realistically, no one knows. What almost everyone agrees on is that whatever raw materials are required to produce a great running back, Dupree has them in abundance. Glynn (Squirrel) Griffing, an All-American quarterback at Ole Miss in ‘61 and ‘62, has seen Dupree at the high school, college, and pro level, and says he is “bigger and faster than Walter Payton, and maybe faster than Jim Brown, too—and I was with the Giants during Brown’s best year so I saw him firsthand. Dupree reminds me a lot of Earl Campbell at his peak, and I think he may know more about running in the open field than Campbell.”

Jim Weeks of the Norman Transcript had a chance to compare Dupree with such all-time Oklahoma greats as Billy Vessels, Tommy McDonald, Steve Owens, Greg Pruitt, Joe Washington, and Billy Sims. Marcus, he contends, “had a lot of rough edges in the areas of blocking and pass receiving—things you pick up with experience. As a runner, just for picking up the ball and running with it, he’s the best I’ve ever seen.”

O. J. Simpson, the best runner of his time, was asked about the great backs who came after him. “I think with all the recent developments in weight training there’s been too much emphasis on running over people,” he said. “My favorite right now is Eric Dickerson. I don’t mean to knock Herschel Walker, who I think has tremendous potential, but I think he relies too much on power, and you can do that only so long in the pros before it begins to take a toll on you. Dickerson doesn’t have quite as much pure talent, but he’s more mature, the way someone like Jim Brown was mature. He shifts speeds, he’s deceptive, and most of all, he knows how to avoid being hit.”

Has O. J. seen Marcus Dupree? “Only once, on TV. If what my eyes showed me was correct, that cat is awesome. To be the size of a linebacker, to have the speed of most wide receivers, and to know how to run the way he does so young… man, you have to wonder what a 190-pound defensive back is thinking about when he’s forty yards downfield and he sees a guy like Dupree start to turn upfield in his direction. I know pros, real veterans, who would hesitate to hit that guy head on.”

For the last two years, articles about Marcus Dupree—and articles about the articles about Marcus Dupree—have practically constituted a light industry. One persistent image seems to resurface: that of a soft-spoken, personable young man, shy and generally affable, who is somewhat puzzled by all the fuss people make over something that has always come so easy to him (though perhaps not quite so easy as we all thought. “He was always setting goals for himself,” says his high school coach, Joe Wood, “always working to improve himself. It seemed like he spent every spare minute working out or in the weight room”).

Looking into Dupree’s background, one finds people he awed, angered, and bewildered—and yet, one never comes across someone who disliked him. Scarcely anyone could recall an instance where he had really lost his temper with the relentless media probing, surely an achievement on a par with gaining 2,000 yards in a season. “That’s Marcus,” says an old high school friend. “He doesn’t try to strike back. He just keeps on going his way and tries his best to act like nothing happened.”

“You got to understand, he’s a Mississippi boy, and that ain’t like bein’ from Arkansas or Tennessee, and it sure as hell ain’t like bein’ from New York or Louisiana.”

Such stoicism has its drawbacks. Marcus’s relationship with the press has been steadily deteriorating for the last two years, and however much blame goes to the press, the principal reason is that Dupree has not yet learned to face up to the responsibilities of being a superstar. At an age when most athletes are dreaming of phone calls from the media, Marcus Dupree has already scattered enough false leads, stood up more interviewers, and dodged enough reporters to fill a book titled In Pursuit of Marcus Dupree. “I like it when I walk in someplace and somebody asks me for an autograph.” he says. “It makes me feel good. When people don’t ask, I start getting worried. I want to be noticed.” It hasn’t yet dawned on him that when writers stop calling, the people with the autograph books stop asking.

Part of Dupree’s problems with the press were the result of a small town Mississippi upbringing that left him diffident around strangers. “You got to understand,” an elderly black neighbor of Marcus’s said. “He’s a Mississippi boy, and that ain’t like bein’ from Arkansas or Tennessee, and it sure as hell ain’t like bein’ from New York or Louisiana.”

Mississippi, as the poet Michael Swindle suggested, “was to America what Ireland was to the British Empire: woefully behind the norm in virtually everything held in value by civilized standards, and producing more genius per capita than Athens in the Golden Age.” Or as a friend of Willie Morris’s, quoted in his book Terrains of the Heart, describes Mississippi: “A place that’s produced the best damned writers in America, that’s always had the courage of the most noble fools, and the most tormenting landscape in all the United States, and a spoken word that would make a drunk Irishman envious; and miscegenation that’s the envy of Brazil, and a sense of the histrionic that would pale the Old Testament, and a past so contorted that it embarrasses the people of Scarsdale.”

Mississippi has seen the much of the worst violence of the civil rights movement. Social progress came slow, measured in painfully short strides. While restaurants in Birmingham and Atlanta were being integrated, Mississippi was just beginning to experience phase one of the movement. As a black civil rights worker told Howell Raines in his oral history My Soul Is Rested, “Our objectives were very clear… not to desegregate white restaurants [but] simply to register people to vote.”

In retrospect, it seems inevitable that the most publicized tragedy of the era should occur in Mississippi, the murders of the three civil rights workers, Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney in 1964. The murders seemed to put the crisis-weary population in a state of shock, and the stigma put on Mississippi has only recently begun to wane. “It really hit home to me,” recalls Glynn Griffing, “when I received letters saying I’d be killed if I took the field for the Giants. That was an experience for me, someone hating me enough to kill me because of what I was and where I was from. When I walked onto the field at Yankee Stadium I looked for a rifle to come sticking out of an apartment building window.”

This is the environment into which Marcus Dupree was born May 22, 1964, just four months after the killings. No black person in Mississippi would deny that integration—real integration—is only beginning there. Yet, there could be no greater testimony to change than the fact that less than twenty years after the horror of the murders, a young black boy, born not ten minutes from where the bodies of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were found, became the biggest sports hero the state had known since injuries kept Archie Manning from winning the Heisman Trophy in 1970.

To author Willie Morris, also, Marcus Dupree represented much more than an extraordinarily talented black athlete on whom national attention was being focused. “I travel about some,” Morris told me at his home in Oxford, “and wherever I go, people ask me where I’m from. Even in other parts of Mississippi their reaction is the same. They say, ‘Philadelphia? Isn’t that where them three civil rights workers were killed?’ It’s been that way for the last seventeen years. Now, for the first time in more than twenty years, people are saying something different. Instead of ‘Philadelphia, where them human rights people was killed,’ it’s ‘You’re from Philadelphia—Marcus Dupree’s hometown.”

Black and white teenagers in Philadelphia, Morris found, “had been emulating the way Marcus walked, his distinctive bouncing gait. A black factory worker said: ‘Remember, he was born in 1964, the same year as the murders. I think he’s a gift. A gift from God, a gift to us. Martin Luther King really brought something to this town. Marcus has, too.’”

Morris, the white intellectual from Yazoo whose literary pursuits have taken him from Oxford, England (on a Rhodes scholarship) to his current writer-in-residence position in Oxford, Mississippi, sees Dupree’s acceptance by the white and black communities as symbolic of the changes in his home state. While an outsider might find his view overly optimistic, consider this scene from a Philadelphia high school football game in 1981: Cecil Price, the deputy sheriff who spent four years in a federal penitentiary for conspiracy in the Philadelphia murders, quietly sitting in the stands watching his son, Cecil Price Jr., hand a cup of water to his teammate, Marcus Dupree. How could such a thing have come about less than two decades after the state’s worst civil rights tragedies? For Willie Morris, finding the answer was tantamount to coming to terms with his own heritage.

An editor-in-chief at Harper’s at age thirty-four (it was his decision to print Norman Mailer’s controversial book-length essay The Prisoner of Sex) and novelist (The Last of the Southern Girls), Morris moved back home to Mississippi after several years in New York. He returned almost precisely as Marcus was beginning his rise to national fame.

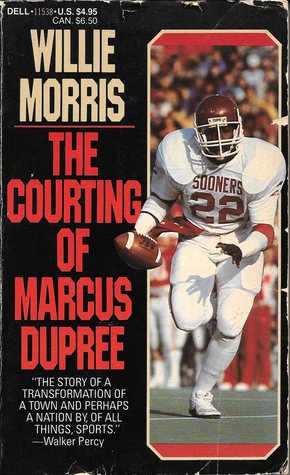

Morris spent the next two years observing Marcus and his pursuit by the nation’s football powers. The remarkable book that resulted, The Courtship of Marcus Dupree, befuddled critics who weren’t certain whether it should be filed under “sports” or “socio-history.” Aside from bloodless tomes such as James Michener’s Sports in America, serious attempts to probe the psychological and sociological meaning of sports in American culture scarcely exist. Sports, Morris seemed to imply, served Mississippi and the South not so much as a diversion—though it certainly did do that—but as a vanguard for integration and a showcase for its possibilities.

At least, that’s the way it seemed possible after Marcus Dupree’s amazing year at Oklahoma. No one could possibly have foreseen the almost surreal occurrences that followed. It seems obvious now that Oklahoma was the worst possible choice Dupree could have made; Texas, Morris’s own alma mater seemed the most logical choice, with the Longhorns already running out of the “I” formation that Marcus figured he’d need to make a run at the Heisman Trophy. Marcus did in fact decide on Texas before stunning the football world with one of his now-famous changes of heart.

Much has been said about Marcus Dupree’s subsequent decision to leave Oklahoma, but not by Marcus, and not by his former coach Barry Switzer. Dupree, when approached on the subject, merely shrugged his massive shoulders and said: “I don’t dwell on negatives. I got to dwell on what’s in front of me now.” Switzer insisted there were are no hard feelings and even offered Marcus tickets to last year’s OU-Texas match, but the fact remains that the Dupree-Switzer clash was one of the more unpleasant incidents college football has witnessed in recent years and raises a number of points regarding scholastic athletics that are far from answered.

“He can’t go out to Oklahoma and be an ordinary freshman ballplayer,” prophesied Coach Wood in 1982. Where, though, could Marcus Dupree have been an ordinary freshman? By the time he reached the Oklahoma campus he was already one of the most famous teenagers in America, an unsophisticated eighteen-year-old who for the previous two years had been showered with praise by a worshipful community. “How can athletes be prepared to deal with the real world?” Bill Russell once asked. “They’ve been on scholarship since the eighth grade!” Marcus’s background had left him totally unprepared for what followed the eighth grade. “He’s a nice kid,” said Jim Weeks, “and a decent student. He just didn’t have any discipline. He never had to have any discipline before he met Barry Switzer.”

Barry Switzer, of course, didn’t care about the complexities of Dupree’s personality—he just wanted the guy who broke Herschel Walker’s records.

That became the party line for much of the sports media—Marcus wouldn’t practice hard, and Switzer wouldn’t stand for it. The issue got hotter when a TV announcer during the OU-Nebraska game claimed that Marcus “practiced only five times in his senior year,” a report that angered Coach Wood. “That’s a lie,” says Wood. “Marcus never missed a practice, never missed a game either. A couple of times he played hurt.” However, a former classmate of Marcus’s, who asked to have his name withheld “because I like Marcus and Joe Wood,” says, “That’s just not true. Marcus usually came to practice, but sometimes he didn’t—and there wasn’t much fuss when he didn’t.” As is often the case when hearing stories about Marcus Dupree, the observer is left wondering if there are two Marcuses.

Barry Switzer, of course, didn’t care about the complexities of Dupree’s personality—he just wanted the guy who broke Herschel Walker’s records. After winning a national title in 1975 and several seasons of contending for one, the, Sooners fell to a 7–4–1 record in 1981 and 8–4 in 1982. Bad luck gang-tackled Switzer: The frequent losses, the angry resignation of assistant coach Larry Lacewell over a personal dispute, a suit by the Securities and Exchange Commission involving Switzer and other Oklahoma businessmen, and soon many Sooner fans were considering what had been unmentionable: namely that the Sooners might benefit from the presence of a less controversial head coach.

Of course, in Oklahoma a head coach who goes 11–1 or 12–0 is beyond controversy, so it’s not surprising that Switzer shifted his famed recruiting charm into high gear in pursuit of blue-chipper Dupree. Former Oklahoma greats Billy Sims and Lucious Selmon (now an assistant coach at Oklahoma) were dispatched to Philadelphia; why Texas didn’t send Earl Campbell is a question the alumni are still asking.

The friction between Dupree and Switzer began almost as soon as Marcus arrived for spring practice. A big-boned young man from a traditionally big family, Marcus weighed in at ten to fifteen pounds heavier than the 220 Switzer had anticipated as his freshman playing weight. Dupree was miffed when Switzer insisted he melt down; no one had ever asked that of him before.

Switzer insists he wasn’t just being picky: An in-shape Dupree was the best safeguard against the recurring hamstring pulls that had been plaguing the back since early in his sophomore year of high school. God, it seems, did give Marcus Dupree a flaw. Just one: his hamstring. “He’s just too powerful for his own bone structure,” says Joe Wood. “He starts and stops so violently you wonder that he doesn’t pull something out of joint on every play. The engine is just too powerful for the chassis.”

Dupree never did get down to 220, or even 230. When he dazzled the team in his first scrimmage with three touchdowns in six carries, Switzer was heard to comment that it was “freshman luck”; when the season started and Dupree was on the bench, Switzer told reporters he was simply trying to keep the pressure off his prize freshman. But after losing two of the first three games (in which Dupree carried a total of twenty times), the pressure was on Switzer. He responded by scrapping the wishbone for the “I” and using Marcus as Oklahoma’s primary weapon. Dupree scored his first collegiate TD against Texas in the fifth game of the season; the Sooners proceeded to win seven of the last eight, dropping only a 28–24 heartbreaker to Nebraska. Switzer had salvaged a near-disastrous season, and Marcus Dupree had set a school freshman record of 905 yards. He led the Sooners in rushing and in punt and kickoff returns.

Yet it was Dupree’s greatest game as a college player that drew Switzer’s harshest comments. In the Fiesta Bowl on New Year’s Day against Arizona State, Marcus Dupree was unstoppable. Against a defense that had led the nation against the rush with just ninety-five yards a game, Dupree set a Fiesta Bowl record with 239 yards, including runs of fifty-six and forty-eight yards. Even more amazing was that he carried only seventeen times and played the equivalent of only half the game, coming out three times with a rib injury, a broken finger, and his old nemesis, the hamstring pull. He was the game’s MVP; NBC’s Charlie Jones called him “The Freshman of the Century.”

All of which didn’t improve Barry Switzer’s mood one bit. Oklahoma lost, 32–21, one of several bitter defeats suffered by the Sooners in recent years when they went into a bowl game a clear favorite. Switzer claimed Dupree had been caught from behind twice, that “he’d have scored two more touchdowns for us if he’d come in at 228 pounds.” Although Switzer’s remarks struck many as bizarre—how many more yards can you expect from a freshman back than 239?—it was later revealed that Marcus had indeed put in overtime at the holiday dinner table and may have weighed as much as 240 for the game.

The Fiesta Bowl was the highlight of Marcus Dupree’s amateur career. From there his relationships with Switzer and Oklahoma deteriorated rapidly. He apparently alienated many Oklahoma supporters (and miffed more than a few coaches and players) when he was quoted in the summer of 1983 as saying, “If I rush for 2,000 yards and we win the national championship, they’ll have to give me the Heisman Trophy”—though in fact he was merely echoing the sentiments of college football writers all over the country who felt he would become the first sophomore winner of the award. The capper came on the first day of spring practice when Dupree reinjured the hamstring and missed most of the team drills. Switzer, of course, felt that the problem stemmed from Marcus’s refusal to get in shape and rehabilitate the injury during the winter months.

“Dupree is lazy,” Switzer told reporters before the season started. “Everything has always come too easy for him.” In Switzer’s defense, it should be pointed out that the other Sooner offensive backs had complained about the constant media focus on Dupree—though one observer is quick to remind you that “they just wanted Barry to see to it that Marcus showed up to practice on time. It wasn’t a question of not liking Marcus, it was hard to find someone who didn’t like Marcus.”

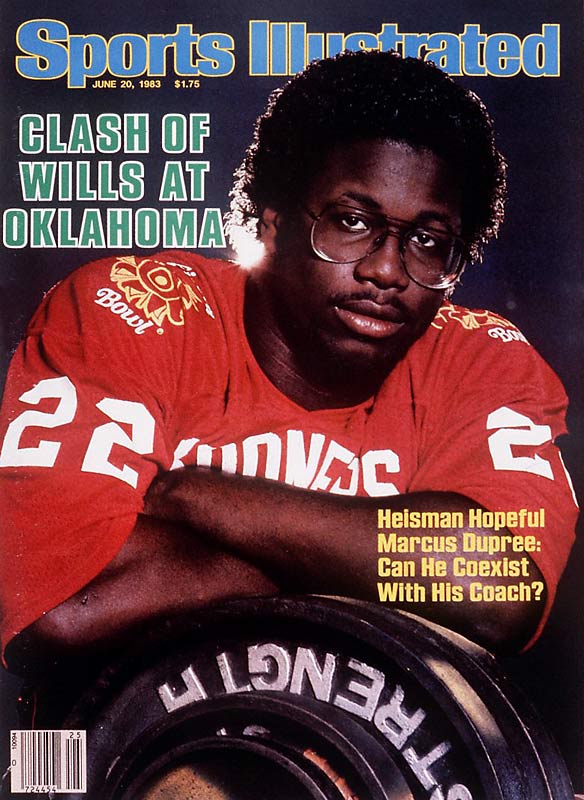

An early summer cover story by Doug Looney of Sports Illustrated either blew the lid off or the entire situation out of proportion, depending on whom you spoke to. Willie Morris—who oddly enough was never consulted by SI, though at this point he was widely recognized as the world’s most intensive Dupree scrutinizer—accused Looney of “portraying for the nation a slovenly, malicious prima donna. The young man so described bore scant resemblance to the one I had grown to know. I was gratified that many sports people around the country who also knew him came to his defense, and none more so than his fellow Mississippians. The Jackson papers cited Dupree’s work with white and black children, his self-discipline as an athlete, his role in the emerging decency of his town and state.”

Dupree, in Looney’s account, came off as less than an indifferent student, but Morris points out that Dupree’s 2.23 grade-point average, though not exactly scholastic All-American, was no lower than many of Marcus’s classmates. Dupree had agreed to pose for the infamous cover story without knowing its slant and once more felt betrayed by the sports writing establishment. His relations with the press reached an all-time low; on a couple of occasions he showed up an hour late for interviews. On several others, he failed to show up at all.

When the ‘83 season got underway Dupree learned the cost of not being in shape—at least Barry Switzer’s idea of shape. Through the first five games he rushed for an average of 5.8 yards a try, excellent for most backs. Still, sharing the tailback workload with talented freshman Spencer Tillman, he totaled only 369 yards. No one was happy with the situation, and certainly not Marcus, who was no whiz at math but was capable of calculating that no one who carried the ball twelve times a game was likely to win the Heisman Trophy. After the bitter loss to Texas, Dupree left the University of Oklahoma. No one knew it at the time, but it was the end of Marcus Dupree’s college career. He made no statement to the press.

An angry Switzer told reporters: “He’s never been a real part of this team. I’ve never seen a player take off like he did after a game and not come back. It seems that he didn’t care who won.” A week later on the CBS NFL Today pregame show, Switzer made what amounted to, for him, an apology: “I made a mistake in publicly criticizing [Dupree] after the Fiesta Bowl . . . that kind of public criticism was too negative. But,” he added, “he was out of shape. If he’d been in shape he might have gained 400 yards.” One phone-in call to an Oklahoma radio station indicated Sooner fans were about evenly split on who was most at fault, Switzer or Dupree. Jim Weeks probably summed up the root cause of the Dupree-Oklahoma problem best: “In his mind, Marcus is still living back in Mississippi.”

The subsequent search by the nation’s sports media for Marcus Dupree rivaled the FBI’s hunt for Patti Hearst. When he surfaced several days later in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, he was discovered by accident. Gene Phelps of the Hattiesburg American spotted him coming out of a shopping mall. “I asked him—not so much businesslike but just out of concern—what his plans were. He seemed to have his mind already made up. ‘I’m going to Southern Miss,’ he told me.”

For Dupree-watchers outside Mississippi, this is where the Reverend Ken Fairley enters the Dupree saga. Marcus was stopped by Hattiesburg police while driving the Reverend’s Trans-Am. Dupree had also put in some time working in Fairley’s Christian bookstore, as apparently had Reggie Collier, Louis Lipps, and other black athletes from Mississippi whom Fairley, in his other life as a sports agent, represents.

Pinning down the Dupree-Fairley relationship isn’t easy, but several impressions have begun to emerge, principally, one, that Marcus Dupree proceeded to enroll at Southern Mississippi; two, that Fairley was employed by Southern Miss in the admissions department and that the reverend and the university parted company around the time Marcus left Southern Miss and, three, that for all intents and purposes, Fairley now functions as Marcus’s agent, as well as an older-brother figure and adviser.

Herschel Walker’s decision to leave college and sign a multimillion-dollar pact with the New Jersey Generals of the NFL wanna-be USFL naturally caused writers to speculate on Dupree’s future. Undoubtedly pro football had been in the back of his mind during the trouble at Oklahoma. “I can’t take the Heisman Trophy into a store and buy something,” he was quoted as saying, and providing for his mother and Reggie had always been foremost in his mind. He was apparently sincere in his desire to play for the University of Southern Mississippi, going through the elaborate procedure of signing up for classes and claiming that he’d sacrifice the season-and-a-half demanded by NCAA regulations before he’d be eligible to play football again.

Like so many people who track down Marcus Dupree these days, I found him almost by accident.

As for the United States Football League, his only comment was: “I’m not the least bit interested in professional football. No way. I definitely plan on playing my next down of football at Southern Mississippi.” The commissioner of the USFL, Chet Simmons, continued to deny that the new league would be going after underclassmen and that “the Herschel Walker case was exceptional.”

Three weeks later Marcus Dupree signed a pact with the New Orleans Breakers of the USFL said to be in excess of $6 million, making him, at nineteen, one of the youngest professionals in football history—not to mention Mississippi’s first black teenage millionaire. “Was he right or wrong?” said Gene Phelps. “I don’t know. I do know that if someone offered me $6 million, I’d probably take it.”

It took me five months, sixty-one long distance phone calls, two trips from New York to Mississippi, fruitless trips to New Orleans and Philadelphia, Mississippi, and no less than six canceled interviews to finally catch up with Marcus Dupree.

Like so many people who track down Marcus Dupree these days, I found him almost by accident. I heard he would be speaking at an NAACP meeting in Oxford and decided to rent a car and make the drive from Birmingham in the hope of catching it. An exasperated plea for more specific information from Ken Fairley’s office netted me a curt comment from the good Reverend Fairley: “We don’t need you. You aren’t the first writer that’s come down here looking for Marcus, and you won’t be the last.” I felt marginally better when I learned that Brent Musburger and a CBS camera crew had been kept waiting for more than two hours at a Pizza Hut after ABC had been promised an interview and then shelved in favor of CBS.

I had been advised to try to talk to Marcus without the Reverend Fairley around, which I took to be good advice if only because trying to conduct an interview with an agent or representative around is like trying to read Playboy with your wife turning the pages. I found a great deal of resentment toward Fairley in Mississippi sporting circles, but I didn’t take it to mean much; he is, after all, a relatively recent phenomenon, especially in the Deep South, namely the young, hip, black businessman who understands and knows how to represent the young, hip, black athlete.

The Reverend Fairley is charming, articulate, and manages to watch over his clients’ interests without being obtrusive, which is fortunate for football writers because they are going to be seeing a lot more of him in the coming months, and fortunate for me because I had as much chance of talking to Marcus without him being present as I would have of tackling Marcus in an open field.

As the three of us retired to a Ramada Inn banquet room for our talk, I realized I had been studying Marcus Dupree for half a year without having spoken a word to him. He looked surprisingly trim for a player who’d missed most of his first USFL season with injuries—I would have been surprised to find he weighed 225—and a little weary of the prospect of going through his life story one more time. I felt a little sorry for him; after months of trying to track him down, all I could think of to break the ice was, “Are you tired of interviews?”

“Yes! I got tired a long time ago. I guess I don’t mind it that much. I just don’t have too much to say about what people want to talk to me about.”

“You mean about Marcus Dupree?”

“Well, yeah, sort of. I mean, I don’t go around thinking about Marcus Dupree all the time, so why should I want to talk about him so much?”

“What about reading about Marcus Dupree?”

“I don’t anymore.”

“Do you read the sports pages?”

“I read the hometown paper, what the team did and all. I like to keep up with ‘em.”

“Do you recognize yourself in any of the stuff written about you?”

“Naw, not really. It’s . . . I don’t know, it’s strange, like when I would read about all these athletes when I was a kid and I’d wonder, ‘Yeah, but what are they really like?’ Now, often I read about me, it’s like I’m reading about someone else. It doesn’t seem like me.”

“Do you feel the need to set the record straight?”

“Someday, maybe. Right now, a lot of people have their own idea of who Marcus Dupree is. I can’t change that.”

“One of the reasons for that is because you changed your mind about so many things in such a short time—which college you’d attend, leaving Oklahoma, leaving Southern Miss, pro ball—people are left to speculate on why you would have changed your mind so often.”

“Well, one of the reasons I think I’ve been through these changes is that I was getting caught in situations before—realize that now, but I didn’t then—before I had been able to think things out, feel my way out.”

“Like going to Oklahoma?”

“Like going to college at all. There was so much pressure, so many people wanting to know where I was going. It’s hard to pick the one place that’s right for you when you get so many different people trying to convince you their place is the best. Before you know it, it’s time to choose.”

“Did you ever stop to think about what you’d do if you could do it all over again?”

“I don’t know. I might make the same mistake again.”

“Knowing what you know now, what if you did it over?”

“If I could do it over, I’d stay in Mississippi. I think I’d go to Southern Mississippi.”

“Why?”

“I don’t think I was ready to go out of the state yet. I like Southern Miss. I probably should’ve gone there in the first place.”

“Didn’t national recognition have a lot to do with it?”

“Yeah, it did. Southern Miss doesn’t get the national attention that a lot of schools do. But later you find out national attention isn’t everything.”

“And it’s near to home.”

“Yeah Southern Miss is near to home.”

“Speaking of which, Portland isn’t. How do you feel about going there?”

I had known Marcus for less than an hour and I already felt that odd twinge of protectiveness I had heard in so many people’s voice when they spoke of him.

(A furtive glance at Fairley, who remained impassive. There were several different rumors floating concurrently, among them that Fairley and a group of businessmen were going to buy Marcus’s contract and sell it to a USFL team closer to home, say Birmingham or Memphis; a last minute business deal would keep the much-traveled Breakers in New Orleans; and Marcus would launch an antitrust suit against the NFL regarding its eligibility rules.)

“I’m not sure. I don’t have anything against Portland. People tell me it rains a lot, and you never see a leading rusher who plays in the rain. That worries me a little. But, basically, I’ll play anywhere.” (Three months later, arriving in Portland, he told UPI, “I was coming to Portland all the time.”)

We talked for another thirty minutes about food and music and how you never see the same kind of enthusiasm in football once you get past the high school level—things that Marcus discussed with enthusiasm and which were obviously still important in his life. He said when he got up to leave, “My pleasure.”

I had known Marcus for less than an hour and I already felt that odd twinge of protectiveness I had heard in so many people’s voice when they spoke of him—a strange feeling to have about a young man who stands four inches taller than you and outweighs you by almost fifty pounds. Though Marcus Dupree isn’t easily shattered, people’s hopes and dreams are, and Marcus will be carrying those of many people along with the football this spring for the Portland Breakers. I hope he will be up to it. I kept remembering gonzo sportswriter Sebastian Dangerfield’s dictum: “Whom the gods would destroy, they send to the pros too soon.”

Major national debates arose as to whether or not a Marcus Dupree or Herschel Walker should be allowed to play in the pros, when it’s obvious that the real question should he: Why are they in college in the first place? And, yes, the Marcus Duprees inspire millions of boys to extend their possibilities, to surpass the limits of their own lives—but what about the thousands who don’t know they can never make it and who will wreck their bodies and possibly their lives by shelving school to try for a piece of the same pie Marcus Dupree cut into?

And how much of this should legitimately be the concern of Marcus Dupree, not yet twenty-one, with a family to provide for and one precarious hamstring away from being an ex-football player?

“I’d be lying if I said I didn’t like the money, the glamour, and the challenge of football,” says Marcus. “But there are times when I wish I could just go back to a time when I was a kid and you got together with your friends just to play some football. When football was just about football.”